I’ve always considered that starting an article, review or profile by stating how hard it is to write about a specific author or book is a dishonest and poor act of writing. Yet this time I have to admit that I do find writing about Tuono Pettinato extremely difficult, for several reasons. One of them is that I find it so hard to write about him in the past tense. And I’d rather not see him historicized, as much as he deserves to be known, studied, and considered one of the most influential Italian comic artists ever. My reasons are only emotional, so I think I’m not being dishonest. Besides, even when he was alive, in all the years I’ve been writing about comics, I’m not sure if I’ve ever written about him. Before and beyond considering him one to be of the most talented contemporary cartoonists, not only in Italy, I’ve always preferred to consider him a friend - someone to look up to, and a sweet and brilliant person I was lucky to know.

Tuono Pettinato is the nom de plume of Andrea Paggiaro. The name came from Jorge Luis Borges' The Library of Babel, and it means “combed thunder” (so from now on he will be referred to just as Tuono, which means thunder, as we all used to call him).

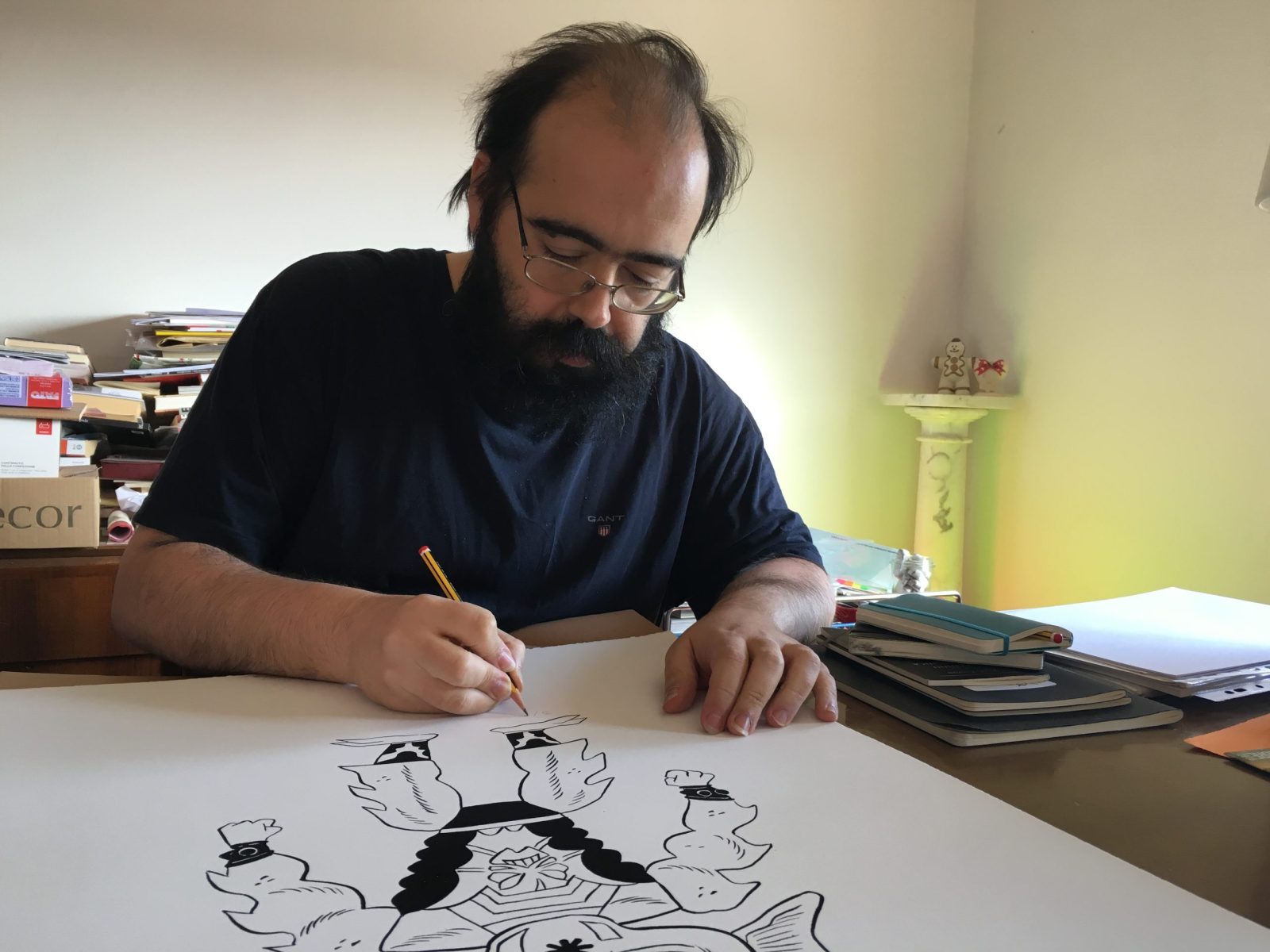

Tuono died on June 14th, 2021, after a year-long struggle with complications of a severe disease. He was born in Pisa and lived there. He was only 44 years old, and his death has left the Italian comics scene and all his readers devastated. Only a few knew about his condition; his illness was kept private. Months after his death, for many it is still hard to cope with that. He was the kind of artist you would find in every convention, always sitting at his publisher’s table, tirelessly drawing, always offering a kind and warm smile to readers and fellow artists, and always supporting younger local artists.

English-speaking readers may have never heard of Tuono Pettinato, as none of his books are translated into English, nor French. And that is a shame. Only one of his books was published outside Italy; Enigma. La strana vita di Alan Turing (“Enigma. The Strange Life of Alan Turing”; written by Francesca Riccioni, published in 2012 by Rizzoli Lizard) was translated into Spanish and Japanese. In Tuono’s signature style, the book is a seriously funny and bittersweet biography of the British mathematician and father of modern computer science.

When Tuono was alive, I’d always thought that his comics deserved more exposure outside Italy. He and his work are extremely influential in the Italian contemporary comic scene, and I’m sure the influence will last long. Tuono was an honest and brilliant creator who brought new blood to Italy’s long tradition of humor comics, the ideal heir to the legacy of Bonvi, creator of the Sturmtruppen and Cattivik among many other characters, who also left us too early in the '90s.

Tuono’s comics were impregnated with so many influences. The DIY culture was one of them; probably the first, besides literature and cinema. At university Tuono studied at DAMS in Bologna: the faculty of arts, music and drama, founded in 1971 by, amongst others, the writer, philosopher and comics scholar Umberto Eco.

Tuono started his career self-publishing comics in the early 2000s, while he was also part of the hardcore punk scene with the band Laghetto, in the role of the (toy) guitar (fake) player (he wasn’t actually playing the toy, he was just there on the stage, with his guitar, acting like the toy was working as a normal guitar). Another soon-to-be comic artist was Laghetto member Ratigher (aka Francesco D’Erminio, also chief editor of Coconino Press from 2017 to 2021), who played real bass guitar and sang. Tuono published his first comics and collective magazines with the small DIY label Donna Bavosa, which was mainly involved in the production of punk records.

In 2008, along with Ratigher, Dr. Pira, Maicol&Mirco, and LRNZ—all of them now prominent figures in the Italian comics scene—Tuono founded the comics collective Super Amici (“super friends”). Super Amici curated two comics anthologies, Hobby Comics and Pic Nic, which showed an above-average quality compared to most of the small press productions of the time.

In the early 2000s, at the beginning of his career, Tuono’s drawing style was sketchy and naïve. The quality of his art quickly grew from showing a rough line to a soft and delicate one, still minimal but very essential, fluid, and effective - at the same time, his humor was already keen, yet simple.

Corso di fumetti dozzinali (“A Course of Tawdry Comics”) published by Donna Bavosa, was one of the first comics he created. The minicomic already revealed his profound love for contradictions, his humble self-mockery, and his deep knowledge of the medium. The book was a simple and crude pamphlet, but I’m pretty sure many of those who’ve read it at the time (just like me) immediately recognized Tuono’s sparkling genius shining behind the booklet’s rough art. One line has been stuck in my head for years: «If you need to draw a famous character you’re not able to draw, just draw it from a distance.» As silly as it could sound, the sentence was imbued with the shy and modest, subversive attitude that runs through all his work.

In the following years, Tuono created several graphic novels: about historical figures; about himself; about dogs going to war; about traveling to Japan; about climate change; even about Kurt Cobain.

After illustrating several short novels in the early 2000s, in the late years of the decade Tuono started working with the imprint Rizzoli Lizard, publishing his first graphic novel, Garibaldi. Resoconto veritiero delle sue valorose imprese, ad uso delle giovani menti (“Garibaldi. Truthful Report of His Bold Deeds For the Purpose of the Young Minds”, 2010), about the Italian patriot Giuseppe Garibaldi, followed by many others: the aforementioned Enigma; Nevermind (2014), a biography of Kurt Cobain; We Are the Champions (written by the YouTuber Dario Moccia, 2016), a biography of Freddy Mercury; Non è mica la fine del mondo (“It’s Not the End of the World”, written by Francesca Riccioni, 2017), about climate change; Big in Japan (written by Dario Moccia, 2018), a travelogue about Japan; and Chatwin. Gatto per forza, randagio per scelta (“Chatwin, Cat by Nature, Stray by Choice”, 2019), his last book, about a cat that desires to live a free life and leaves the safety of his home.

After illustrating several short novels in the early 2000s, in the late years of the decade Tuono started working with the imprint Rizzoli Lizard, publishing his first graphic novel, Garibaldi. Resoconto veritiero delle sue valorose imprese, ad uso delle giovani menti (“Garibaldi. Truthful Report of His Bold Deeds For the Purpose of the Young Minds”, 2010), about the Italian patriot Giuseppe Garibaldi, followed by many others: the aforementioned Enigma; Nevermind (2014), a biography of Kurt Cobain; We Are the Champions (written by the YouTuber Dario Moccia, 2016), a biography of Freddy Mercury; Non è mica la fine del mondo (“It’s Not the End of the World”, written by Francesca Riccioni, 2017), about climate change; Big in Japan (written by Dario Moccia, 2018), a travelogue about Japan; and Chatwin. Gatto per forza, randagio per scelta (“Chatwin, Cat by Nature, Stray by Choice”, 2019), his last book, about a cat that desires to live a free life and leaves the safety of his home.

In the meantime, he also published Corpicino (“Little Corpse”, 2013) and L’Odiario (“The Hate Journal”, 2016), both for a smaller publisher, GRRRzetic; the anthology of early material Apocalypso! Gli anni dozzinali (“Apocalypso! The Tawdry Years”, Coniglio Editore, 2010); and the childhood memoir Il magnifico lavativo (“The Magnificent Slacker”, TopiPittori, 2011).

L’Odiario and Corpicino are particularly noteworthy. The first is a heartfelt short book, almost a pamphlet, in which Tuono channeled many of his struggles, his negative thoughts that so often conflicted with his kind spirit. Corpicino is a dark graphic novel that explores the theme of child murder and the morbid coverage of these kinds of crime stories made by the news and television. The book was later studied in a criminology course at the University of Genoa, thanks to its deep and documented analysis of the cultural phenomenon of mass interest in brutal crimes. Tuono liked to joke about death, as Ratigher remembered in his elegy at Tuono’s funeral, and this is evident in the cover of Hobby Comics 7 which will be published in 2022, a year after Tuono’s death.

In Tuono’s works, tragic drama and silly irony could find a place on the same page—not only in the case of Corpicino—deconstructing reality in order to detect its most ridiculous aspects and bring them to the surface, naked, disrobed of every rhetoric.

Among his creations, the one he was most devoted to—and also the one that remains unfinished—is a graphic novel entitled Bastardi da guerra (“War Bastards”), first serialized in the magazine Pic Nic. The story was about a pack of dog soldiers in the Vietnam War. One of the last times we spoke he showed me a page from that book («Super secret!» he said, so it will remain in that chat), after which we talked about books and documentaries about the Vietnam War, a common interest for the both of us. It is such a shame that he didn’t have the chance to finish that story after so many years of work.

As Michael Rocchetti (from Maicol&Mirco) mentioned on Facebook, saying goodbye to Tuono knowing that you will not have the chance to read Bastardi da guerra is like saying goodbye to Andrea Pazienza if Pompeo had never been published and never would be. (Pompeo is arguably the most relevant work by Andrea Pazienza, a true underground hero of Italian comics who died in 1988 at age 32.) Since the first time I’ve read Bastardi da guerra, I’ve always had the impression that it was a project Tuono was really fond of. Because in his true vein there was not only humor, as we clearly discovered with the book that can be arguably considered his best work: Corpicino.

Tuono was a prolific artist; his short comics and strips featured on magazines such as Repubblica XL, Linus (his one- or two-page contributions were able to catch the true spirit of famous cartoonists in short biopics), and Internazionale (with a long-running strip entitled Mediocri), while also collaborating with zines and DIY collectives, or with for the online magazine Fumettologica with the strip Tippi Tuesday.

His creativity could not be contained. Neither could his brilliant intelligence and profound knowledge of pop culture and high culture. With his gags he was able to bring together a profound love of life with a cynical black humor, while showing a unique ability to open a breach on entire worlds to which anyone could relate.

Since the beginning of his career, with his sketchy and simple style, Tuono demonstrated a fascination both for American comic strips classics like Peanuts, Pogo, Beetle Bailey, Kaz’s Underworld, Maakies, and the work of the Italian master, Bonvi. He was one of the most relevant and influential artists of his generation, while never working outside the field of comics (the exception being cameos in a tv series and a movie). In a time when comics and comic artists are so often attracted by other mediums, and Italy makes no exception—just think of comic maestros Gipi and Igort, both also movie directors—Tuono was a pure cartoonist. Italy has a long tradition of humor comics, and the current scene is full of great talents (Dr. Pira, Sio, Maicol&Mirco, just to name a few), but among them Tuono Pettinato was the one with the most versatile and richest style, considered by many as the one who started this new wave.

Capable of bringing to the surface a hidden and funny feature from every character or situation (fictional or real), and above all, always prone to display a genuine human side in every character (even if it was GG Allin or a black metal singer), Tuono could tackle any subject, as is shown by his many biopics, or by his comics made in collaboration with the Comics & Science project curated by the Italian National Research Council. His writing was acute, fresh, and sharp. He admired the work of Bill Hicks and Larry David, among many other contemporary comedians. Tuono’s humor wasn’t easy to encapsulate; sometimes black, always light, even when bringing the heaviest of subjects. His gags do not rely too much on trivial pop culture (where too many find easy success); his references are higher while his puns are straightforward. He loved wordplay; he loved it so much that you could see him delivering his gags and puns on Facebook, starting all sorts of challenges with friends.

As some realized on the day of his death, and many of us already knew, Tuono was loved by many. It was not the kind of love that buys you lots of fans and followers, if that can be called love. The love of Tuono was genuine. Readers fell in love with an intelligent artist, a modest and shy person. Yet it was so stunning to see him remembered in the Italian Parliament on the day of his death, by a congressman whose speech was delicate and precise in the hard task of describing Tuono’s life and art in a few words.

As some realized on the day of his death, and many of us already knew, Tuono was loved by many. It was not the kind of love that buys you lots of fans and followers, if that can be called love. The love of Tuono was genuine. Readers fell in love with an intelligent artist, a modest and shy person. Yet it was so stunning to see him remembered in the Italian Parliament on the day of his death, by a congressman whose speech was delicate and precise in the hard task of describing Tuono’s life and art in a few words.

Everyone who knew Tuono was a friend to him, readers or colleagues. June 14th, 2021 was a day of mourning for the whole comics community in Italy, and in the hours and days that followed his death you could see tributes and farewells coming from everyone on social media, from his closest friends to comics masters such as Altan (Pimpa) or Silver (Lupo Alberto).

And yet, why did I write this, if none of his many comics are available in English or French, and probably almost no one who is reading this will have the chance to actually discover Tuono’s work? Part of me thinks I just had to say thank you to Tuono in all possible ways I knew, for all he gave, and for the legacy he left. Another part of me hopes someone who reads this knows Italian, and will read a book of his or just a strip, and will experience his genius so that we will share the love of Tuono with one more person. My hope is also that publishers outside Italy will decide to translate his work. Yet I can’t help but think it doesn’t sound right to me, now - too late for him to see it happen as he deserved.

Now his self-portrait has entered the renowned Uffizi Gallery in Florence, and will remain in the permanent portrait collection of the museum as part of the Fumetti nei musei (“Comics in Museum”) initiative: Gli autoritratti degli Uffizi, a one-of-a-kind project that gathers over 50 portraits of Italian comic artists in the museum that hosts the Primavera by Botticelli and many other masterpieces. The exhibition is dedicated to him.

Tuono Pettinato has left this world, but he will never leave the world of comics, as any great cartoonist deserves.