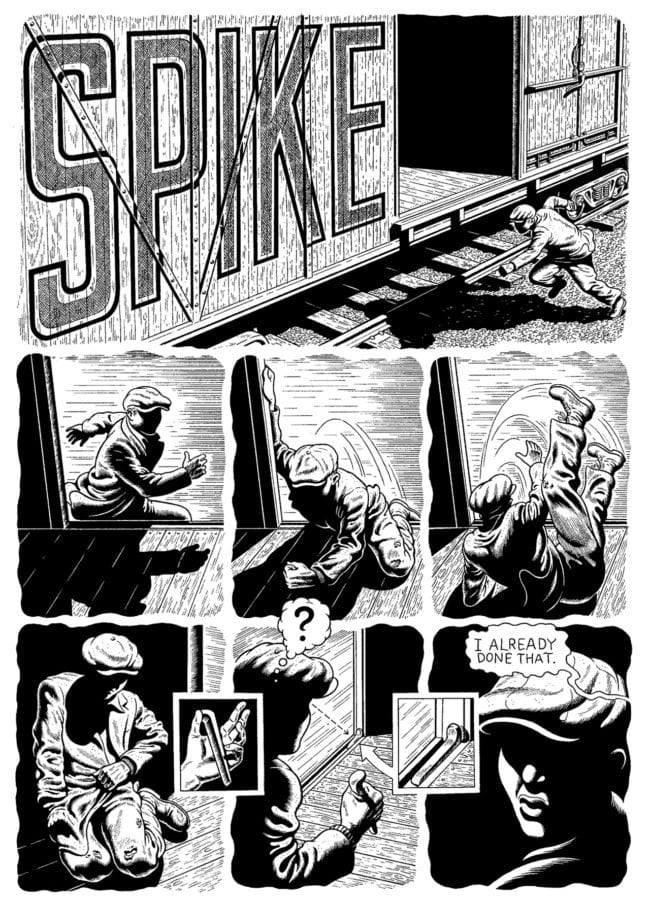

In two books – 2008’s Abandoned Cars and 2014’s The Lonesome Go – Tim Lane delves into the “Great American Mythological Drama” of melancholy drifters and dime-store angels, of riding the rails and desperate attempts to make it before it’s too late. And in the new issue of Happy Hour in America, a series he began back in 2003, he chronicles movie star Steve McQueen’s attempts to disappear from popular culture. (The story’s existence proves McQueen’s failure.) Here, Lane discusses influences, fame, American cartoonishness, and the fate of the single issue.

Martyn Pedler: Why comics? You’re not afraid of prose sections in your work, so why not prose?

Martyn Pedler: Why comics? You’re not afraid of prose sections in your work, so why not prose?

Tim Lane: That’s a good question. I had that debate with myself for years. I always had aspirations to draw, but I didn’t know what form it would take in my adult life. I only knew that I wanted to be a communicator of stories. I’d been inspired by comics when I was growing up, but I guess I never took them terribly seriously. At the time, Kitchen Sink Press was doing reprints of Will Eisner’s The Spirit, and some other publisher was doing reprints of old EC comics, and that’s the stuff I gravitated toward the most when I was a pre-teen. 11 or 12. Then my interest in comics sort of dropped out, so all through college I was trying to figure out whether I was going to be a writer of prose or if I was going to be a visual artist.

Shortly after college, I was turned on to the work of the Hernandez brothers, and Daniel Clowes, and a graphic adaptation that had recently come out of Paul Auster’s City of Glass by Paul Karasik and David Mazzucchelli. Reading those books showed me that the kind of storytelling I wanted to do could very much be done in comics. But prior to that, I wrote a novel. Took about three years, and by the time I was finished, it felt wrong that there weren’t pictures in it.

You describe your work as being about minor characters in American mythology. I love that. Can you say what “American mythology” means to you?

You describe your work as being about minor characters in American mythology. I love that. Can you say what “American mythology” means to you?

I can do my best. I should preface it by explaining that when I’m talking about what I call the Great American Mythological Drama, I think of it not as the title of a thesis paper so much as perhaps a banner outside of a P.T. Barnum kind of surreal show. There’s an element of tongue-in-cheek about about that phrase for me.

But I do take it seriously, too, and I think what it is trying to understand is all of this mythology surrounding what America means or what it is supposed to represent. All of the – what would be the word? – all of the monuments that I think Americans tend to worship and believe in. To try to come to come to terms with what of those things are true, and what are no longer true. What are these artifacts of the ideals of America, and what do these artifacts mean in contemporary life?

It’s interesting you say “contemporary life”. What role does nostalgia play in your work?

Oh, it plays a big part. I play around a lot with the idea of time. I enjoy making it ambiguous as to what the particular era or decade is in the stories that I’m writing. Because for my life experience – so it’s a very personal thing, I’m not trying to make any wide-sweeping declaration about what American life is like – but from my life experience it’s very much like the thrift store of Americana. You have thrift stores filled with a lot of interesting artifacts, a lot of interesting clothes from different periods of time. The characters that I try to write about for the most part are both literally and figuratively dressed in the clothes of the American past.

When you’re using familiar characters, character types we’ve seen before, how do you keep them alive?

Well, I do my best to. I’m sure there are plenty of people out there who who might think that they just come off as stereotypes. I don’t know. That’s part of mining the field of Americana. It’s not just about cars and clothes and buildings and ideals, it’s also about archetypes. I tend to write mostly from the point of view of people who are living on the underbelly of the American dream. I think that story is pretty ever-present. I don’t think the idea could be worn out – I mean, the territory could become worn out, but I think with a little creativity there’s enough universality to that type of archetype that it can cleverly be reconditioned. In a similar way to, say, how Quentin Tarantino will take tropes of film that you might call stereotypes, but just by putting them in a slightly different light, in a slightly different context, they are renewed. I think the best storytellers can do that. That’s what I aspire to anyway.

I am a person who is very steeped in a kind of cultural tradition: my grandfather was a World War Two veteran, and my father and my uncles were also veterans. The lessons they taught me were very infused or inspired by a kind of American idealism that, in my own life, I have not seen too much evidence of. So in a sense it’s like living in a haunted house. And that’s what I try to explore in my work: what are the rooms of that haunted house?

Your stories can be about celebrity: celebrity in their use of real-life stories, which reaches a kind of peak in the new issue with Steve McQueen escaping his fame, and in those who don’t have celebrity and feel like something is missing in their lives. Do you think that’s fair?

Your stories can be about celebrity: celebrity in their use of real-life stories, which reaches a kind of peak in the new issue with Steve McQueen escaping his fame, and in those who don’t have celebrity and feel like something is missing in their lives. Do you think that’s fair?

Absolutely. I think that’s very fair. Have you ever seen the movie Fight Club? That came out right when I was in my 20s and I could really relate to it. The core of the message of that movie spoke directly to my experience, and I think the experience of a lot of people my age. There was a scene in it where the Brad Pitt character says: you know we were raised to believe that we were going to be rock stars, that we were going to be famous, that we were going to be important people. Well guess what? We’re not. He makes the point that the majority of us were raised on this notion of “be all you can be”, and that celebrity was the end-all. All of these things were at your fingertips, and it was just a question of whether or not you had the wherewithal to pursue that and grab the brass ring. Well, that wasn’t true.

This really is the material that’s like a splinter in my brain. There’s a lot of notions about living in America, like upward mobility, and getting a good job, and expecting that with that will come regular raises and family and every year will get better and better and better if you just live your life “right” – whatever the hell that is supposed to mean. But those paradigms aren’t reality anymore. So again it’s like you’re living in this haunted house. You’re haunted by these ideas of what America was supposed to be and represent. But in fact that sort of dream is much more elusive, and maybe even non-existent.

I don’t mean to come off as someone who is who is anti-America. Not at all. In fact, my relationship with this country is very much like my relationship with, say, my grandfather, or my dad. I love them very much. But I’m also very critical of the contradictions.

Years ago, you said comics were perfect for depicting the American dream because America is inherently cartoonish. What do you think now?

I still think that’s true. Look at our current president! I mean, talk about cartoonish, in a very scary way. But there’s always a kind of cartoonishness, or an exaggerated quality, to elements of American culture. Let’s just put it this way: it’s not a surprise to me that there is a great deal of anxiety and depression and things like that happening in America, in our culture. On one hand, you hear in newspapers – “newspapers”, talk about nostalgia, right? – in the media and in advertising, this constant reaffirmation of “you can lose 50 pounds” and “you can be as healthy as you’ve ever been” and “you can be all these things”. There’s no end to what you’re capable of attaining. But then the average person looks at their own lives and starts to question, like, why haven’t I attained those things? I think a lot of people end up with inferiority complexes because they start thinking it’s their fault that they haven’t attained whatever this American dream is supposed to be. The truth is that the cards are not dealt fairly to everybody.

One of the things I like most about your comics are the sympathetic, emotional “performances” you get out of your characters, especially with your use of close-ups. Is that something you think about a lot?

One of the things I like most about your comics are the sympathetic, emotional “performances” you get out of your characters, especially with your use of close-ups. Is that something you think about a lot?

Oh yeah. I’m very empathetic. I am so prone to making mistakes. Doing things foolishly. My heart goes out immediately to people who are falling from grace. I find it very easy to sympathize with people. Upon any close examination of self, you’re going to recognize a ton of imperfections and if you don’t relate, or if you can’t accept and even appreciate the humanness of other people’s imperfections, then it makes you a bit two dimensional, doesn’t it?

When you’ve got these long-running stories, coming out over a span of years – do you have endings planned for stuff like The Belligerent Piano?

I wouldn’t say that I have it all worked out, specifically. I have a skeleton idea of how that story progresses, but I always want to leave room for improvisation. The Belligerent Piano story in its current state is very much inspired by the daily strips of Dick Tracy, those old newspaper strips. We live in a time now when those old comic strips are being anthologized. So you get these huge volumes of Dick Tracy from 1935-36, then 36-37. You end up with nearly a wall of Dick Tracy.

What’s interesting is that Chester Gould never set out to write this extraordinarily circuitous and elaborate graphic novel. I imagine at the time he was just going from story to story. But now we have this great opportunity through the anthologization, if that’s a word, of all of his work. I also think of Milton Caniff and Terry and the Pirates and Steve Canyon and that kind of stuff. Suddenly they have this graphic novel quality to them. They’re these epic stories, kind of like Dostoyevsky.

What’s interesting is that Chester Gould never set out to write this extraordinarily circuitous and elaborate graphic novel. I imagine at the time he was just going from story to story. But now we have this great opportunity through the anthologization, if that’s a word, of all of his work. I also think of Milton Caniff and Terry and the Pirates and Steve Canyon and that kind of stuff. Suddenly they have this graphic novel quality to them. They’re these epic stories, kind of like Dostoyevsky.

And so I was really inspired by those Dick Tracy serials, those daily strips, when I was working with The Belligerent Piano story in its current state. All of that is so say: I do have an idea of how the story ends, how the story progresses, but just as Chester Gould might go off on a tangent, I always leave room for that improvisational possibility.

This interview came to me with a subject you wanted to discuss: the fate of the traditional comic book. The single issue.

That’s something I’m interested in at least stating an argument for: the resurrection of the traditional comic book. There’s such a rich and and colorful history of the traditional comic book and how it developed in America. I’m a strong proponent of it – both for philosophical reasons but also for very practical reasons. From what I can see, comics is in a place where graphic novels are what’s most popular. They’ve grown to become quite exquisite art books. The only complaint I have is that for people like me – I have a son and I have a wife and we have bills to pay – it’s very difficult to to be able to spend a couple hundred bucks to buy, let’s say, four graphic novels. It’s getting to the point where it’s so expensive to get your hands on the material. The great thing about comic books is that they are, and always have been, inexpensive and for the average person. It started with kids, you know, for a dime. I’d like to see that come back because it’d be nice if comics were more affordable, and I think the traditional comic book is one way to make that happen.

Also as a creator, it allows the opportunity to have work out there more often. Instead of having to wait six to ten years for the next book to come out, you can be publishing elements of of your bigger projects as well as a one-off story ideas, be a little more experimental. There’s all kinds of valuable aspects to the traditional comic book that I think would benefit both the the people who read comics and the people who make comics. It’s just kind of a pity that we’re seeing fewer and fewer of them and, as a lot of people have told me, they’re pretty much dead. That particular form of the medium is pretty much dead.

To play devil’s advocate, is this just nostalgia for the single issue? Is it something we’ll evolve beyond?

I’m sure we probably will. Like you mentioned before, I said something about how the comic book was the perfect medium to tell American stories. One reason is because of the cartoonishness, the exaggerated quality of the culture as a whole. But also comics in their original form – and when I say that I’m talking about the late 1930s when they first came out, to the 40s and 50s – it is this perfect union. They were democratic because they were inexpensive enough so that anybody could get their hands on them. They were one of one of the original mass-produced pop culture artifacts. These things are very American concepts.

You’ve got this democratic, egalitarian kind of thing where it’s available to anybody with ten cents, but there’s also this huge capitalistic side to it where so many of the original comic book publishers were in it just to make a quick buck, which is also a very American sort of thing. So to me it’s like twin brothers who are polar opposites in personality, coming together in this one medium. To me that that’s that’s another wonderful reason why comics – at least the kind of comic stories I want to tell – are really well-suited to the traditional comic book.

But to answer your question: no doubt it’s nostalgic. No doubt I’m going to be as successful as John Henry was. I don’t think traditional comics will survive. But I’m trying one last gasp now before they go under completely.

Tim Lane will appear at Desert Island for a book signing and limited edition print send-off on Monday, December 18th.