Late in life, Jack Kirby returned to his youth. After a long, distinguished career he drew his first unequivocally autobiographical story, "Street Code", in 1983 (published 1990). In it, he remembers the dreary tenements on the Lower East Side of New York that he called home during the Depression, the unspoken love between he and his immigrant mother, the way his American identity was defined along ethnic fault lines, and the gang violence that became a constant, socializing factor for him.

It is an intensely sensed story, as always more or less improvised on the page. It ends abruptly with a sharply brooding self-portrait of the artist as a young man. He stares directly at the viewer with the glare of someone beyond his years, disgusted by the way of life he and his peers are forced to adopt. Kirby thus offers us a key to the art that led him out of this misery and with which he here brings that former reality to life. He aspires toward the arch-American narrative of social transcendence, ubiquitous not least in popular culture – and at the time he drew this story expressed most potently in New York’s still youthfully burgeoning hip hop culture.

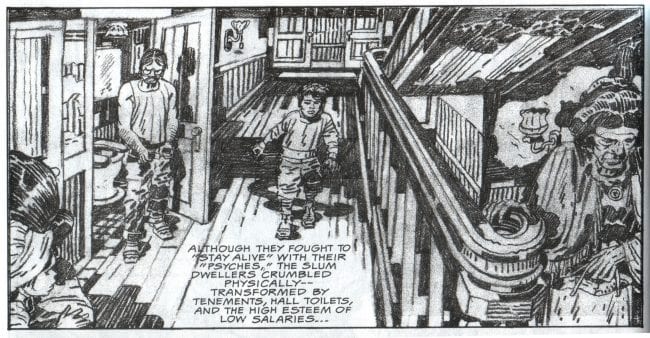

It is important, however, that this theme is merely suggested. Kirby does not tell us about success, but focuses on the struggle for survival that underlies all of his work, as a theme and as its motivating factor. This struggle became traumatically acute to him during the allied invasion of Normandy, in which he participated, but its roots were in the streets of his childhood. As he writes here, in his oddly poetic prose: "Although they fought to "stay alive" with their "psyches," the slum dwellers crumbled physically – transformed by tenements, hall toilets, and the high esteem of low salaries…"

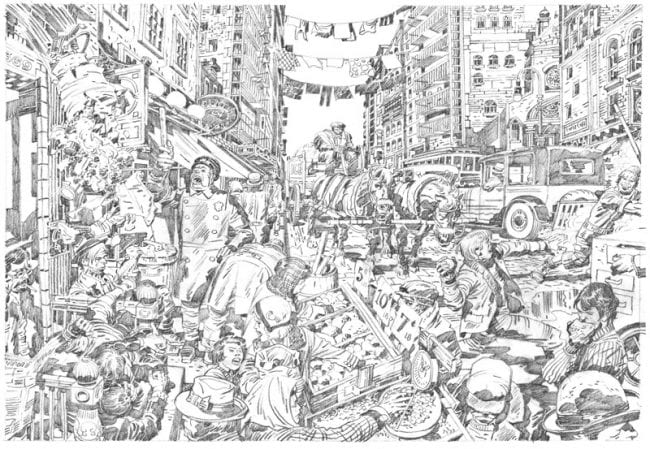

Visually the story is executed in the quasi-cubist style he developed as he matured and which became second nature to him. Despite having spawned a thousand imitators, it still ranks among the most original in comics history. The panorama of the central spread, which vividly renders the tumultuous bustle of, perhaps, Delancey Street offers a stirring parallel to his earlier images of the Hunger Dogs slaving under the ashen skies of Apokolips in his masterwork New Gods.

This is the point. The life force expressed in angular, stylized strokes and closely cropped, tightly arranged panels is the same here, in an autobiographical story, as it is in his heroic epics. His intent is the same, his vision deeply personal.

He strikes at this parallel with particular poignancy in the first panel of the story, its first self-portrait. It depicts the young Kirby reflected in a mirror, surrounded by everyday objects as well as more affective ones, including photographs, which situate him and his family historically. He is pulling a sweater over his head, and all we can see is the lick of black hair at its top. The face which confronts us so directly in the story’s last panel is obscured here, along with most of his body, cropped as it is by the mirror frame, as if it were a comics panel within the comics panel. This suggests the fragmentary nature of memoir, its status as subjective truth plucked from a greater, infinitely more complex continuum.

Pictures like these reveal the richness of Kirby’s creative vision and his instincts as an artist. The metaphor makes sense, but unlikely to have been conceived with explicit intention. His work invariably has overtones of automatic writing. He draws his pictures, chooses his words and rarely looks back. This sometimes results in fracture plotting, jarring juxtapositions and jerky continuity, but it preserves the crackling energy of the creative moment. As the reader, you are never in doubt that he means it, and that the stakes are high.

As we know, a mirror image reverses reality, at times magically. The inner disquiet that animates young Kirby as we meet him in the story is implicitly the one he will later unfold so beautifully in his art, nourished as it is by apocalyptic imagination, but also by a belief in the necessity of moral action. The superhero figure, thus, is the perfect vehicle for Kirby because it insists on the Good and the True beyond life as lived.

Reading between the lines it is clear, however, that the universe is unconcerned with this. The arch-villain of his late work, Darkseid, represents the ultimate consequence of such thinking. He is Kirby’s Lucifer, eternally rebelling against an unfathomable order. The promise of total control that he seeks in the so-called Anti-Life Equation is fascist – a potent metaphor for the forces against which Kirby fought in his comics as well as on the battlefields of Europe. More fundamentally, however, it is the paradoxical end point of our will to power and autonomy. An affront to the Cosmos.

Through the mirror drift the lost titans, chained to the fragments of the devices they used in their attempts to smash the Final Barrier.

"Street Code" was first published in Argosy vol. 3 no. 2, 1990 and reprinted in John Morrow and Jon B. Cooke, eds. Streetwise, TwoMorrows Publishing, 2000 and Mark Evanier, Kirby -- King of Comics, Harry N. Abrams, 2008.