(Pt. 1)

--

1934-35 – Tank Tankuro, Gajo Sakamoto (Presspop Inc., 2011)

You will notice that absolutely none of the books described throughout the various installments of this guide are marketed toward 'manga readers' as a demographic - put simply, the publishing wisdom is that they will not buy them in great enough numbers to warrant the focus. One needs only glance at the New York Times sales charts and the applicable shelves at your local Barnes & Noble to see how even contemporary seinen and (especially) josei manga are crowded out of visibility by poppy youth comics; for the Tokyo-based Presspop, long focused on international alternative culture, it must have seemed merely prudent to chase the same generalist 'art'-comics audience which bolstered the reputations of Osamu Tezuka and Yoshihiro Tatsumi. And if that meant supplanting Gajo Sakamoto's own art with Chris Ware's rendition of same on the cover, well - I suppose that's business.

It is difficult to remain annoyed with Tank Tankuro, however; it is far too valuable a book. Other manga releases have afforded readers translated access to the comments of Japanese writers and critics, and not a few 'historical' releases append supplemental texts by western experts, but this one sees editor/co-translator Shunsuke Nakazawa offering a a rare and extensive overview of the pre-Tezuka eon, from the formative influence of Punch and Puck on Meiji period artists through the popularization of newspaper cartooning, the rise of children's entertainment magazines, the development of emonogatari and the proliferation of akahon - all rushing towards the cataclysm of World War II, through the American occupation and into the midst of the Tezuka phenomenon.

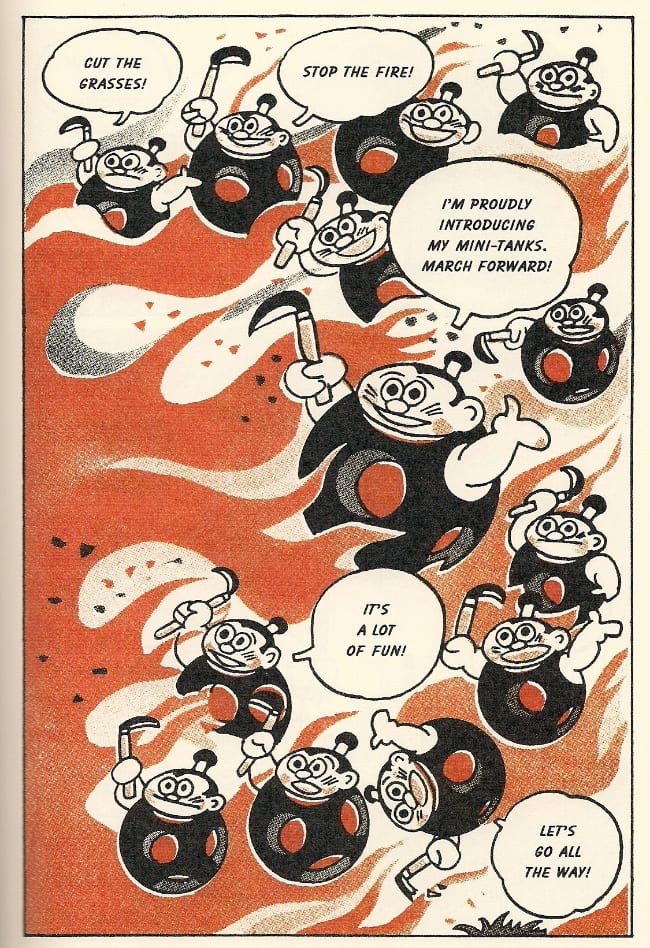

Running parallel to this is the life of Sakamoto himself, who offers additional, personal testimony (penned in 1964), as does his son, Naoki (new to this edition). Sakamoto, we learn, was a trained painter and advisee of emonogatari progenitor Ippei Okamoto, whose dissatisfaction with a children's samurai comic he'd been drawing for a newspaper company ultimately led him to Kodansha's Yōnen Club magazine -- yes, the same Kodansha which publishes Attack on Titan today -- where he cut loose with an imaginative serial about a strong boy inside an iron ball who can produce any item necessary ("like a chest full of toys," declares the artist) to defeat villains. Tank Tankuro was a big success, enough so that Sakamoto adapted some of the comics material into an experimental emonogatari variant format he dubbed manga-dōyō, with uniform rhyming text accompanying dialogued panels (see above, and note the lack of English-equivalent rhyming). Then, of course, came a collected book edition, the texture of which Presspop perhaps means to suggest through its own deluxe slipcased hardcover production.

It could be that compilation was a mercy for Tank Tankuro. Through the Presspop edition's many supplements, it soon becomes clear that what we are reading is far from a comprehensive document, but probably all that remains - the comic which Gajo Sakamoto began in 1934 is not the manga seen here, as the artist revised the work for its initial collection to make it seem "more manga-like" (per Nakazawa), as opposed to Okamoto-derived emonogatari; the earliest stuff is likely a casualty of fashion. Further, Tank Tankuro continued for years after: first in Yōnen Club, which began to apply politicized pressure to decrease the work's fantasy and emphasize military realism, and later as a newspaper feature in seized Manchuria, where he accepted a government publicity job. All of these episodes are considered lost, as (I'm guessing) are a postwar continuation of the series, created after Sakamoto and his family fled the Soviet incursion and suffered detention in North Korea, crossing south only a year later and returning penniless to a burned-down home in Japan.

Mostly, we are told, the artist came to focus on suibokuga, rather than smiling boys sprouting weapons from their iron holes.

Manchukuo, as it was, had been formally established not two years prior to the start of the Yōnen Club tenure for Tank Tankuro. Beaming with confidence, the hero sets out down a road in his debut adventure, traversing neatly from right to left across long horizontal panels. There is nothing reminiscent of the cinematographic juxtaposition of angles associated with Tezuka, or Shichima Sakai, or even Sakō Shishido, whose popularity preceded Sakamoto's; rather, each panel is navigated like a stage, or a scroll, Tankuro grinning throughout like a divine force, his victory assured and his dialogue amusingly blasé in addressing every threat. These are all battles, but they are play battles, loaded with elephants, octopi and turtles, silly and ramshackle and unfailingly buoyant. They are like the games my friends and I played during Operation Desert Storm, where we would excitedly discuss which countries the United States could beat up, and nothing we'd glimpse grudgingly on the news dissuaded us from the enduring validity of our calculations. Like Sakamoto, we played fervently, and without irony.

Still, one does not suspect the artist is untruthful when he states that the minister of education "hated" manga. "Fantasies and dreams were almost considered vices," Sakamoto remarks, characterizing Tank Tankuro as representative of a "free-thinking American style." Even works so immersed in martial play can be considered threatening, when you understand that at their core lies not ideology, but anarchy. "W-- what? War? This is what I was hoping for," Tankuro-kun shouts, barreling across panels, nearly slicing a bystander in half with his katana, then snatching a mikoshi from its bearers' hands, only to trip from over-excitement and drop it into the sea. This is not satire, it is juvenile high spirits - but the latter can be threatening to the authoritarian, as it may swing capriciously from pleasure to pleasure. And it is pleasure first which reports from this troubled, antic work.

--

1937 – Norakuro, Suihō Tagawa, as excerpted in Kramers Ergot 6 (Buenaventura Press & Avodah Books, 2006)

And then, unavoidably, comes Norakuro - the 1931 creation of Suihō Tagawa, and the undisputed colossus of Japanese comics in the 1930s, known in English only through a 23-page excerpt from its seventh of ten revised, colorized, pre-occupation compilations. Norakuro-kun and his Rabid Dog Troop smash pidgin-talking opposition pigs by land, sea and air, thwarting a wicked shogun and creating a fortress of peace in which dogs, pigs and sheep might harmonize under swordpoint. One should never entirely trust excerpts, especially those as provocative as this, although individual images threaten potency enough to reduce any contrary dialogue to efforts at calling an apple a peach. I mean:

One page of explanatory text accompanies the work. "These comics are propaganda," Paul Karasik doomily intones, likening the work to ukiyo-e battle scenes and illustrated dispatches from the Russo-Japanese War. I would add that the habit of depicting humans as anthropomorphic animals in picture narratives dates back to 12th century emakimono, where the intent was often to poke fun at the subjects. From this, perhaps, we might launch an inquiry toward complicating such critiques of Norakuro.

In Empire of Dogs: Canines, Japan, and the Making of the Modern Imperial World (Cornell University Press, 2011), for example, Aaron Herald Skabelund cites to anthropologist Masao Yamaguchi for the contention that Norakuro "contested the myth of the Imperial military as immune to surrender, tears, or humor." (Pg. 152) Indeed, Natsu Onoda Power, in God of Comics: Osamu Tezuka and the Creation of Post-World War II Manga (University Press of Mississippi, 2009), quotes Junko Takamizawa, a literary critic and Tagawa's spouse, as arguing that "[t]he numerous failures of the clumsy Norakuro promoted anti-war sentiments through humor." (Pg. 29)

Admittedly, she is not, one imagines, a disinterested observer -- nor would she be the first to discover 'anti-war' impulses as a means of downplaying participation in a catastrophic military affair -- and Power promptly cites to writer Jun Ishiko's quotation from a survived suicide attack soldier: "I believe it was the children's comics which drove us into the war." (Ibid.) Skabelund also asserts that the popularity of Norakuro "introduced soldiering to millions of youngsters, many of whom entered the armed forces and went to war with such images in their heads," suggesting that Tagawa's "idealized picture of military life" is inseparable from his "demythologiz[ing] the mystique of the Imperial Army." (Pg. 152)

It gets stickier. Thomas LaMarre, in "Speciesism, Part 1: Translating Races into Animals in Wartime Animation," a contribution to the third edition of the annual Japan-focused academic journal Mechademia (University of Minnesota Press, 2008), identifies numerous Norakuro-derived animated cartoons of the period, noting differences between them and typical live-action national policy films, both in the notional irreverence of Norakuro-kun himself, and the films' willingness (apparently unique to anime and manga of the time) to depict enemy combatants; indeed, LaMarre observes that one 1935 cartoon in particular, in which Norakuro-kun disguises himself as a tiger to entrap a larger representative of the species, can be read as an allegory for Japanese duplicity in the exploitation of Korean labor, although he cautions that "it is difficult and probably impossible to sustain an allegorical reading based on a one-to-one correspondence between an animal species and a people or nation," asserting that the anthropomorphism in the work "come[s] to embody the paradoxical stance underlying the Japanese war of racial liberation: races are simultaneously delineated and 'liberated' (allowing free reign to swarm), simultaneously projected and overcome." (Pgs. 87-92) Manga critic Tatsuya Seto, meanwhile, in 1001 Comics You Must Read Before You Die (Universe, 2011), notes that Norakuro-kun's original animal foes were monkeys, positing the initial funny animal scheme as a quintessentially Japanese pun on the phrase "dog-monkey relationship," denoting less a specific, racial attack than a general disagreement between people, though he flatly states that Norakuro the character was eventually used as "a vehicle to accelerate support for the war." (Pg. 77)

But it is again Shunsuke Nakazawa, in Presspop's Tank Tankuro, who offers the most potent insights. Tagawa, he notes, was not a manga lifer; few were, so early on. In fact, he was once an abstract painter and performance artist, affiliated with the Taishō period "Mavo" group under his birth name, Michinao Takamizawa; the Japan Times reports that the young, radical Takamizawa once smashed the glass ceiling of an exhibition hall with rocks in protest of the growing conservatism of a prominent arts organization. Mavo was influenced by Futurist and Constructivist art, and informed by anarchistic theories active in Japan following the Russian Revolution - while hardly uniform in practice, participants generally opposed class associations and promoted individualist action, seeking to obliterate extant institutions.

How, then, did the renamed Tagawa find himself stoking the passions of youth in war? It is childish, perhaps, to presume that radicals remain committed to upheaval even while they age; eventually, one may assume a pragmatic stance in the direction of national winds. In Mavo: Japanese Artists and the Avant-garde, 1905-1931 (University of California Press, 2001), Gennifer Weisenfeld suggests that Tagawa came to use his celebrated platform as a means of raising morale among youth in difficult times, going so far as to travel to Manchuria to comfort Japanese troops as early as 1939. (Pg. 254) Osamu Tezuka himself -- as translated by Power, see above -- was cooler, but not unsympathetic, characterizing Tagawa among "opportunists" who did not personally support militaristic activity, but struggled nonetheless toward getting their works published in a hostile environment: "Of course I agree that he should be held accountable (for his war participation), but there are plenty of others who did the same in other fields." (Pg. 33)

What everybody basically agrees upon, though, is that Norakuro was not spared the fate of other manga from its era; dismissed, finally, as a triviality, it was withdrawn from publication as WWII raged on and resources grew meager. In Presspop's Tank Tankuro, Gajo Sakamoto writes of encountering Tagawa once in Shinkyō, capital of the Manchukuo puppet state. "We saw each other and laughed, 'ha ha ha......' and there was a deep meaning to the laugh that was beyond words."

And in the ensuing years, it must be said, Norakuro was hardly cast out. The character was revised into more of a stock hero, set apart from militarism. Anime episodes were produced as late as 1988. It is said that in his prime, in the '30s, Norakuro-kun was almost as big in Japan as Mickey Mouse, and such love doesn't just vanish in a flash. The comics, I will add -- the colored, hardcover comics, the deluxe comics -- are achingly beautiful, redolent with the creator's thorough, progressive education in the wider arts; these small excerpts alone are lovelier, I think, than anything Tezuka produced in his entire career. I didn't need to 'look up' Kramers Ergot 6, because I simply remembered these pages, these 69-year old comics which immediately outshone not a few of the contemporary scene's best and brightest. This character, whom I imagine continuing his fight, futilely - pursued by Soviet bears out of Manchuria, ambling blurry and ruined back to his island home, collapsing amidst the rubble, and finding himself lifted up, like Borodin's Prince Igor, and praised as a hero despite himself.

***

PLEASE NOTE: What follows is not a series of capsule reviews but an annotated selection of items listed by Diamond Comic Distributors for release to comic book retailers in North America on the particular Wednesday identified in the column title above. Be aware that some of these comics may be published by Fantagraphics Books, the entity which also administers the posting of this column. Not every listed item will necessarily arrive at every comic book retailer, in that some items may be delayed and ordered quantities will vary. I have in all likelihood not read any of the comics listed below, in that they are not yet released as of the writing of this column, nor will I necessarily read or purchase every item identified; THIS WEEK IN COMICS! reflects only what I find to be potentially interesting.

***

SPOTLIGHT PICKS!

Over Easy: *Lots* of good word surrounding this Drawn and Quarterly release from veteran cartoonist, illustrator and television writer Mimi Pond, an account of time spent as a young woman serving hungry customers of a diner in the late 1970s, a veritable community of characters. At least one more volume is planned, on top of the present 272 pages. Interview with Tom Spurgeon here. Preview; $24.95.

The Eltingville Club #1 (of 2): In which writer/artist Evan Dorkin presents a grand finale to his recurring series of glimpses into the lives of male geeks - not the network sitcom-ready types (though a Welcome to Eltingville pilot did air on Adult Swim), but mean mini-dictators of geek culture purity: probably the types who grouse about the whole idea of 'geek culture' anyway, when not ego-tripping off the cultural prominence. This issue charts the decline and fall, while #2 presents an issue-length coda set 10 years later. From Dark Horse, where it all began in Instant Piano circa '94. Preview; $3.99.

--

PLUS!

Someplace Strange: And the Epic reprints keep on coming! Last year brought Titan's collection of the Chris Claremont/John Bolton feature Marada the She-Wolf from the pages of Epic Illustrated, and now Dark Horse brings a 1988 Epic Graphic Novel, also from Bolton, with writing by Ann Nocenti, in which kids take on the boogieman in a world of magic and anxiety. I've never read this -- totally forgot it existed, in fact -- but this whole period of oddball creator-owned genre-y projects from a Marvel subsidiary (on which 1988 would be near the tail-end) fascinates me for its concern with maintaining narrative clarity amongst high-gloss experimentation. Preview; $19.99.

Judge Dredd: The Complete Case Files Vol. 22: Lots of reprints this week. LOTS. Rebellion is way ahead of Simon & Schuster in the Judge Dredd reprints game (22 vs. 8), so you know this is an import item, compiling a solid 340 pages of smack-middle '90s stuff, including the long-ish John Wagner-written story The Exterminator, and a yet-longer Grant Morrison/Mark Millar/Mick Austin collaboration, Crusade, also available separately from S&S. Some super-early Ashley Wood art in here too. Be aware that a $13.99 digital edition has been available for over a month now, released in tandem with the print version's UK debut. Samples; $32.99.

Vampirella Archives Vol. 9: Dynamite is damn far along now, covering issues #57-64 of the original Warren magazines. I would anticipate the entirety of a magazine-length Gerry Boudreau/Gonzalo Mayo/Carmine Infantino Vampi serial, along with shorts drawn by José González, Esteban Maroto, Russ Heath, Alex Niño, José Ortiz, Infantino w' Dick Giordano, and many more. Samples; $49.99.

The EC Archives: Weird Fantasy Vol. 1: But if its older shit you're after, Dark Horse has 216 "remastered" color pages of early EC SF for your pleasure, including contributions by Harry Harrison, Wally Wood, Jack Kamen, Harvey Kurtzman and others. Samples; $49.99.

The Flowers of Evil Vol. 9: Vertical is now just about caught up with the Japanese releases (10 dropped last January) for this Shūzō Oshimi series (now) about the lasting effects of profound youthful experiences on maturing sickos. Oshimi tends to move the plot in three-volume increments, so this one should provide some kind of turning point; $10.95.

A Distant Soil Vol. 2: The Ascendant: This is Image's second release of a newly-restored edition of Colleen Doran's signature series, assembled from original art and digitally-cleaned copies as a means of simply getting the work back out. I vividly recall Doran declaring in an interview last year that one of the "big, painted books" from a major comics publisher was temporarily rendered 'lost' in terms of printers' negatives, necessitating a quiet rescue/rebuild from a Spanish edition. Sleep tight, comics; $16.99.

Frank Thorne's Red Sonja - Art Edition: One 'a those big-ass hardcovers where the original art for comics are shot in color, and you practically huff the correction fluid. This time the publisher is Dynamite, and the subject is Frank Thorne, whose 12" x 17" images are displayed for 128 pages. I believe this is Bruce Jones/Roy Thomas-written stuff from Marvel Feature in 1976. Samples; $150.00.

A Princess of Mars: And finally - prominent around the same time (with the Studio) was Michael Wm. Kaluta, whom IDW now spotlights through 20 full-page, full-color illustrations (and other drawings) supplementing the text of Edgar Rice Burroughs' 1917 novel. Kaluta's next comics project should be a Kickstarted continuation of his and Elaine Lee's sprawling SF series Starstruck, but consider this your not-a-comic for the week; $29.99.