1931 - The Four Immigrants Manga, Henry (Yoshitaka) Kiyama (Stone Bridge Press, 1999)

This Saturday, the San Francisco Public Library will host foundational manga historian Frederik L. Schodt for a talk on a book he translated fifteen years ago: Manga Yonin Shosei, initially self-published by one Yoshitaka Kiyama, a first-generation Japanese immigrant (or Issei) to the United States. Kiyama, a student artist, had lived in San Francisco since 1904, though his residency became less permanent in the 1920s; apparently printed in Tokyo, Manga Yonin Shosei was nonetheless intended for the eyes of new American immigrants, scripted in a unique blend of Japanese and English that couldn't possibly make sense for any other audience. It was a collection of semi-autobiographical newspaper strips, fifty-two in total, intended for a year's weekly serialization but reformatted instead as a singular original work, thus anticipating the way certain rejected strips would find new life in the later phenomenon of the comic book.

It is also, in a way, the first manga to be released stateside.

But what is the early "manga"? Is it narrative picture scrolls of the 12th century? The whimsical drawings of Hokusai? Or should we start with Rakuten Kitazawa, the artist who popularized "manga" in the sense of caricature - who founded the cartoon-laden Tokyo Puck, and, at the dawn of the 20th century, began publishing multi-panel narrative manga for the western-style newspapers and magazines enabled by new access to advanced printing technology? Perhaps it should be Ippei Okamoto, a newspaper cartoonist and pioneer of emonogatari, whose enthusiasm for American comic strips resulted in full-blown Japanese translations for Bud Fisher's Mutt and Jeff, Frederick Burr Opper's Happy Hooligan, and -- perhaps most crucially -- George McManus' Bringing Up Father, which, in 1924, directly inspired a Kitazawa apprentice, Yutaka Asō, in his creation of the wildly popular Nonki na Tōsan ("The Careless Father" or "Easygoing Daddy"), an American-styled newspaper strip which touched off a wave of merchandise, including collected editions.

Indeed, by 1931, numerous Japanese newspaper comics enjoyed compiled releases, and it could be that Kiyama's exposure to these books -- in addition to stateside compilations of Fisher and the like -- inspired the ultimate publication of Manga Yonin Shosei. Certainly his application of American strip style to Japanese concerns was in keeping with the aforementioned developments in "manga" from the decade subsequent. Of course, there were concurrent evolutions in children's manga, magazines, etc. - we mustn't limit ourselves, though it would be a disservice to Kiyama not to see him as an active force in an ongoing effort at comics synthesis.

Schodt first encountered Kiyama's work in 1980, but wasn't able to bring it to wide, English-only attention until 1999, under the title The Four Immigrants Manga. As you can see, a compromise was struck in the localization; Kiyama's own English lettering was left untouched, which his hand-lettered Japanese (employing a rather tricky, old-timey style, per Schodt's extensive introductory essay) was replaced by a rather bloodless font. This was done both to distinguish the usage of English-as-Japanese from English-as-English, and to ensure Kiyama's rather dense clouds of Japanese dialogue would actually fit the word balloons in bulkier English.

I can't say it's the most attractive solution (and I mean "attractive" in the aesthetic, rather than pragmatic sense), yet to my mind this also underlines the artifice at the heart of Kiyama's endeavor. What the white characters say in this book -- along with the occasional Chinese and black, rudely caricatured in the racist manner of the day -- are never really what they're saying, but what Kiyama and his friends can understand of them, and likewise what the Issei can communicate. In this way, having these words spring up from the same hand that draws their bodies seems appropriate, as their hesitancy shakes with the slapstick of bodies. The Japanese language, in contrast, comes from some eternal interior: thoughtless and automatic, issuing from humans but internalized, and stripped of the consciousness of composition.

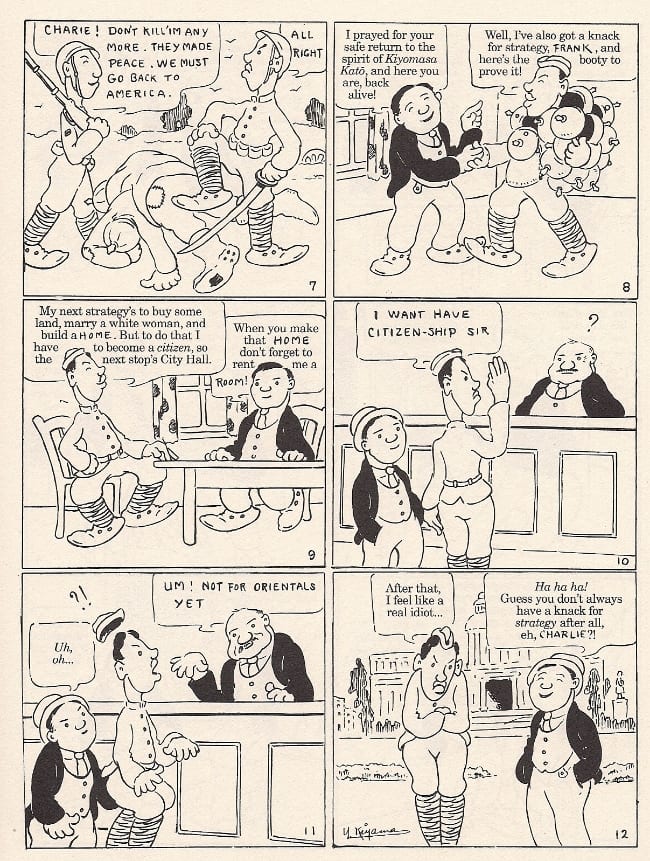

There was much in the way of conscious performance at that time. The name "Henry" was adopted by Kiyama to ingratiate himself to the monied whites he would rely upon for work and lodging. We don't need Schodt's intro to tell us this either; it is presented to us flatly in the first of Kiyama's strips. Subsequent installments transform personal history into comedy vignettes, several consolidated (at times anachronistically) from community lore, and each one wrapped up in a gag by the twelfth panel. There are references to the earthquake of 1906, Margaret Sanger, the Alien Land Laws, and the difficulty of romance when men outnumbered women eight to one and miscegenation was illegal. Eventually, Kiyama surrenders the protagonist's role to "Charlie," a student of democratic systems and classic twit. There's even a little action:

This is pretty funny stuff, I think, although Schodt's extensive translation notes draw special attention to the most rueful bit of humor: Charlie's plan to "buy some land, marry a white woman, and build a HOME" is farcically predicated exclusively on things which were illegal for him to do at the time; "HOME," after all, denotes citizenship, which would not be on offer to Issei veterans of WWI until well after the publication of Kiyama's comic. By that time, the artist himself was coming and going; the final strip of The Four Immigrants Manga discloses the author-as-character's angst over the Immigration Act of 1924, which effectively banned Japanese immigration to the United States. Feeling down, Kiyama decides to start a family back overseas. By 1937, international tensions had guaranteed a permanent stay in Japan, where he died in 1951.

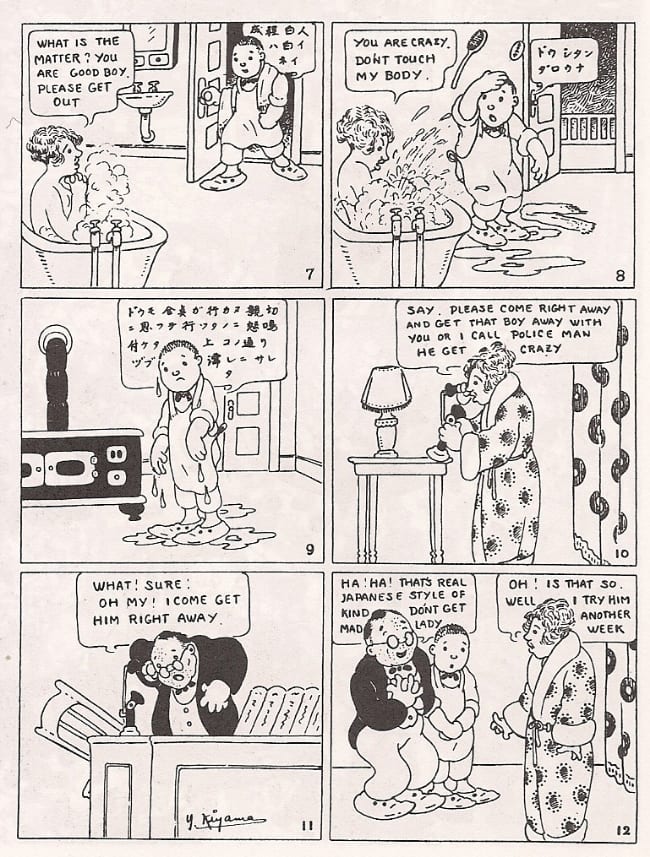

Still, this is not a bitter work, even if some bitterness is atmospheric; it's difficult to see images of adult men referring to employers as "mom" as anything other than painful. Yet looking back to the bathtub gag a ways above - it's raucous, yes, and a little sinister, with its humor premised in part upon the white woman's fear of rape. There is little lasting blame, though. Kiyama has made an honest mistake, and the woman is understanding. She doesn't fire him until a little later, when he inadvertently teaches her beloved parrot to cuss in two languages. It's a struggle, but we'll learn.

***

PLEASE NOTE: What follows is not a series of capsule reviews but an annotated selection of items listed by Diamond Comic Distributors for release to comic book retailers in North America on the particular Wednesday identified in the column title above. Be aware that some of these comics may be published by Fantagraphics Books, the entity which also administers the posting of this column. Not every listed item will necessarily arrive at every comic book retailer, in that some items may be delayed and ordered quantities will vary. I have in all likelihood not read any of the comics listed below, in that they are not yet released as of the writing of this column, nor will I necessarily read or purchase every item identified; THIS WEEK IN COMICS! reflects only what I find to be potentially interesting.

***

SPOTLIGHT PICKS!

Insufficient Direction: From old autobio to new, suddenly we land in the 21st century for a 176-page one-off from Moyoko Anno, a 2005 account of her married life with otaku icon Hideaki Anno, the director behind Neon Genesis Evangelion and (more recently) the unlikely star of Hayao Miyazaki's The Wind Rises. M. Anno is a versatile and talented artist -- a protégé of Kyoko Okazaki, whose influence seems to have hung heavily over Anno's last translated manga release, Sakuran -- but we've never quite seen her in this mode, and that alone should provide a bit of interest. My manga autobio dream translation, incidentally, is errant Sailor Moon creator Naoko Takeuchi's Princess Naoko Takeuchi's Return-to-Society Punch!!, concerning (in part) her lingering inability to follow-up a world-smashing hit with anything of comparable success, but, perhaps in keeping with the theme, I don't think it's ever been collected into a book, let alone slated for licensing. A Vertical release; $14.95.

Rusty Riley Vol. 1: Dailies, 1948-1949: And so the Golden Age of Reprints found respected illustrator Frank Godwin, creator of Connie and, most applicably, this 1948-59 saga of American boyhood among Kentucky horses, scripted by Rod Reed. Classic Comics Press is the publisher, and its 342-page package promises a interview with the late cartoonist's daughter, various bonus illustrations and an introduction by Howard Chaykin; $49.95.

--

PLUS!

Cape Horn: It's a relatively Euro-heavy week outside of the spotlight, and I'll start with this Christian Perrissin/Enea Riboldi release from Humanoids, a 2005-11 series which I'm guessing stands in a distinctly French tradition of very polished, 'dignified' adventure comics; certainly that's what we got from Perrissin's and Boro Pavlovic's El Niño, portions of which Humanoids released back in '05 when they were partnered with DC. I'd expect lots of observable research going into this late 19th century South American period piece, 228 pages in total, concerning the adventuresome journeys of numerous characters - probably a drier, cooler type of action comics thing. A 9.4" x 12.6" hardcover. Samples; $39.95.

Snowpiercer Vol. 2 (of 2): The Explorers: I don't believe Bong Joon-ho's Snowpiercer movie has yet officially opened in the United States -- not that I'd ever know from first-hand experience, given the limited release scheme concocted by the Weinstein Company in exchange for agreeing to distribute the two-and-a-half-hour-plus film unedited -- but I enjoyed a good chuckle nonetheless at the very prospect of seeing this material playing out on screen as soon as I read the first Titan Comics collection of the original Jean-Marc Rochette-drawn comics, 'cause hoo-boy is this a relentlessly dour slice of existentialistic-bordering-on-nihilistic SF, positing the whole of the human experience as a rigidly horizontal progression between classes of advantage, pausing only to reflect upon the futility of revolution and the guarantee of eventual, comprehensive annihilation before locking its already-agency-free protagonist into a room with himself and denying him any assurance that a world even exists outside of his own line of sight. But I guess knifes and forks were pounding on tables as France chanted SE-QUEL, SE-QUEL, so following the death of original writer Jacques Lob we got a pair of millennial follow-up albums written by Benjamin Legrand, both of which ought to be included in this 144-page hardcover; $24.99.

The First Kingdom Vol. 3 (of 6): Vengeance: And also from Titan Comics, we've got another 208 pages of reprints 'n supplements pertinent to Jack Katz's 1974-86 super-series, no doubt cleaned-up and re-lettered as all prior volumes have been. I think the next book is where we get into some never-collected stuff; $24.99.

Where Bold Stars Go to Die: One international comic I've frequently seen mentioned since its 2010 North American release is ELMER, an allegorical work about intelligent chickens by Filipino creator/publisher Gerry Alanguilan; SLG handled the NA edition, and now they're bringing another project written by Alanguilan, with art by the late Arlan Esmeña. It's about a man's obsession with a VHS sex starlet, which possibly gets surreal, if I'm reading the solicitation right; $7.95.

Loving Dead: Ha, get it? A pun is a good enough reason for a re-release, as this Stefano Raffaele project used to be called Fragile, back when it was serialized in the English Métal Hurlant; there was a DC/Humanoids collection in '05, but this one's a hardcover, 176 pages chronicling romance among dead people with disintegrating bodies. Humanoids was also serializing Jerry Frissen's & Guy Davis' The Zombies That Ate the World around the same time, less than a year after The Walking Dead launched, when this zombie stuff didn't seem quite so much like a trend. Samples; $19.95.

Valérian Vol. 6: Ambassador Of The Shadows: Cinebook is here too, with another 8.5" x 11.3" album by Pierre Christin & Jean-Claude Mézières, its 48 pages this time coming from 1975. Dargaud had released its own English edition of Ambassador of the Shadows back in '84, which you sometimes still see sitting around in dusty corners of comic book stores; by this point the series had become more confidently satirical, so there's a lot of stuff about diplomatic belligerence and capitalist sub-strata. I think I recall heroine Laureline carrying around a wee critter that shits out money. Very enjoyable, imaginative art; good stuff. Samples; $11.95.

Henry and Glenn Forever and Ever #4 (of 4): Being the conclusion to this Tom Neely-fronted homage to domesticity and art, as Johnny Ryan, Noah Van Sciver and Keenan Marshall Keller make friendly appearances. Microcosm sells it; $5.00.

Sergio Aragonés Funnies #12: It's been more than a year, but twelve issues of a one-man show is notable enough in today's comic books. From Bongo; $3.50.

Graphic Classics Vol. 3: H.G Wells: There's a lot of comics out there I'm not familiar with. I'm barely conversant in those Big Nate comics which grossed north of $3 million last year in bookstores, I wouldn't know a Ninjago if one of 'em assassinated by Congressman (were they in The Lego Movie?), and I'm totally not up on the two dozen releases of Eureka Productions' Graphic Classics line of 7" x 10" short-form adaptations, though a cursory tour of their site reveals contributions by Spain Rodriguez, Shary Flenniken, Hunt Emerson, Mary Fleener - all kinds of people. This is the third edition of their presumably successful H.G. Wells volume, newly expanded to 144 pages, and featuring contributions by Rich Tommaso, Simon Gane and others. Contents; $12.95.

Leonard Starr's Mary Perkins, On Stage Vol. 12: I do believe Classic Comics Press is rapidly nearing the completion of this realist drama strip project, as the feature concluded in 1979. This one -- 264 pages, dailies and Sundays -- carries us into early '74, with an introduction by Don McGregor, whom I believe was working in the Warren magazines around that time; $24.95.

Unknown Soldier: For the life of me, I don't know why Vertigo is releasing a new edition of this Garth Ennis/Kilian Plunkett war-espionage series, serialized in 1997 at the height of the heat generated by Preacher; surely it's too soon after the Preacher television deal (which Vertigo/DC/Warners/whatever is notably not part of) to plan a reissue like this. Is the Kanigher/Kubert concept active again at DC? Regardless, admirers of future Ennis forays into international dirty works like Fury MAX will likely have some interest, and it's moreover a good opportunity to admire Plunkett, a sturdy, well-traveled artist who's worked with Jim Woodring on Aliens: Labyrinth and Mark Millar on Superman: Red Son, in addition to quite a lot of popular work on Star Wars comics and animation; $14.99.

The Ages of Wonder Woman: Essays on the Amazon Princess in Changing Times: Finally, your book-on-comics for the week, a 248-page McFarland collection of scholarly essays on the William Moulton Marston creation, running the gamut from the H.G. Peter originals through the present day. Edited by Joseph J. Darowski. Contents; $40.00.