The conversation outside the café had gone from COVID to the Ukraine to abortion. Dolly said the way to stop unwanted pregnancies was to castrate the men who caused them. Gus offered vasectomy as a compromise. Dolly said vasectomies were reversible. Gus said they weren’t. Arthur said ask Billy; he had one. Irish said it wasn’t just a woman’s issue anyway; half the aborted children would be male. No one knew what that meant, so Big Victor, who had been reading articles about granting elephants and swamps the right to sue to protect themselves,1 suggested embryos be afforded standing to keep themselves from being cut out.

“Or,” Goshkin said, “cartilage threatened by nose jobs.”

Gary Panter’s Crashpad had reached him in two forms.

The foremost was an 11-by-14-inch hardbound (44 pages, $39.99) and the other a 6½-by-10-inch comic (32 pages, $5.99 if sold separately), which came tucked into a pocket inside the hardbound’s front cover, a ragamuffin joey carried by a regal momma-roo. So concealed, Goshkin thought, it might never be opened. The investment-inclined might leave its condition mint. It could lie unseen for generations like a pharaoh’s treasure. Unless called to an outsider’s attention, it might be passed by like Duchamp’s Étant donnés in its museum corner.2

Goshkin would not have been Goshkin’s obvious choice for a reviewer. He had known little about Panter beyond his name. His mind was more on Bob Dylan’s tour reaching Oakland and Warriors-Dallas. The connective tissue was “Loss”. Genius teetering on the frailty of age. Championship banners turning on bad calls and torn tendons.

His research did not put him at ease. Panter, born in 1950, was a half-generation his junior. Panter had been raised by Christian fundamentalist parents who’d traversed in a multitude of states before settling in in Brownsville, TX, while Goshkin’s folks, secular Jews, had been as rooted in Philadelphia as scrapple. Goshkin had gone high school, college, law school, private practice, leveraging, from nooks and crannies, time to write a body of work esteemed by, it seemed in moments that left him alternatively bouncing between bemusement and gratitude for Lexapro - a couple dozen. Panter went from East Texas State to the Los Angeles punk scene, where his Jimbo had become a seminal work (comic strip and book). He had won three Emmys designing sets for Pee Wee Herman. He’d created album covers for Frank Zappa. His paintings has been shown in galleries in four countries. He had been called “the most important graphic artist of the post-psychedelic... period”3 and honored by MoCCA for elevating the art form.

Goshkin did not think his lack of familiarity and kinship should disqualify him. They might get him somewhere fresh.

We are stardust

We are golden

And we’ve got to get ourselves

Back to the garden

-Joni Mitchell, “Woodstock”

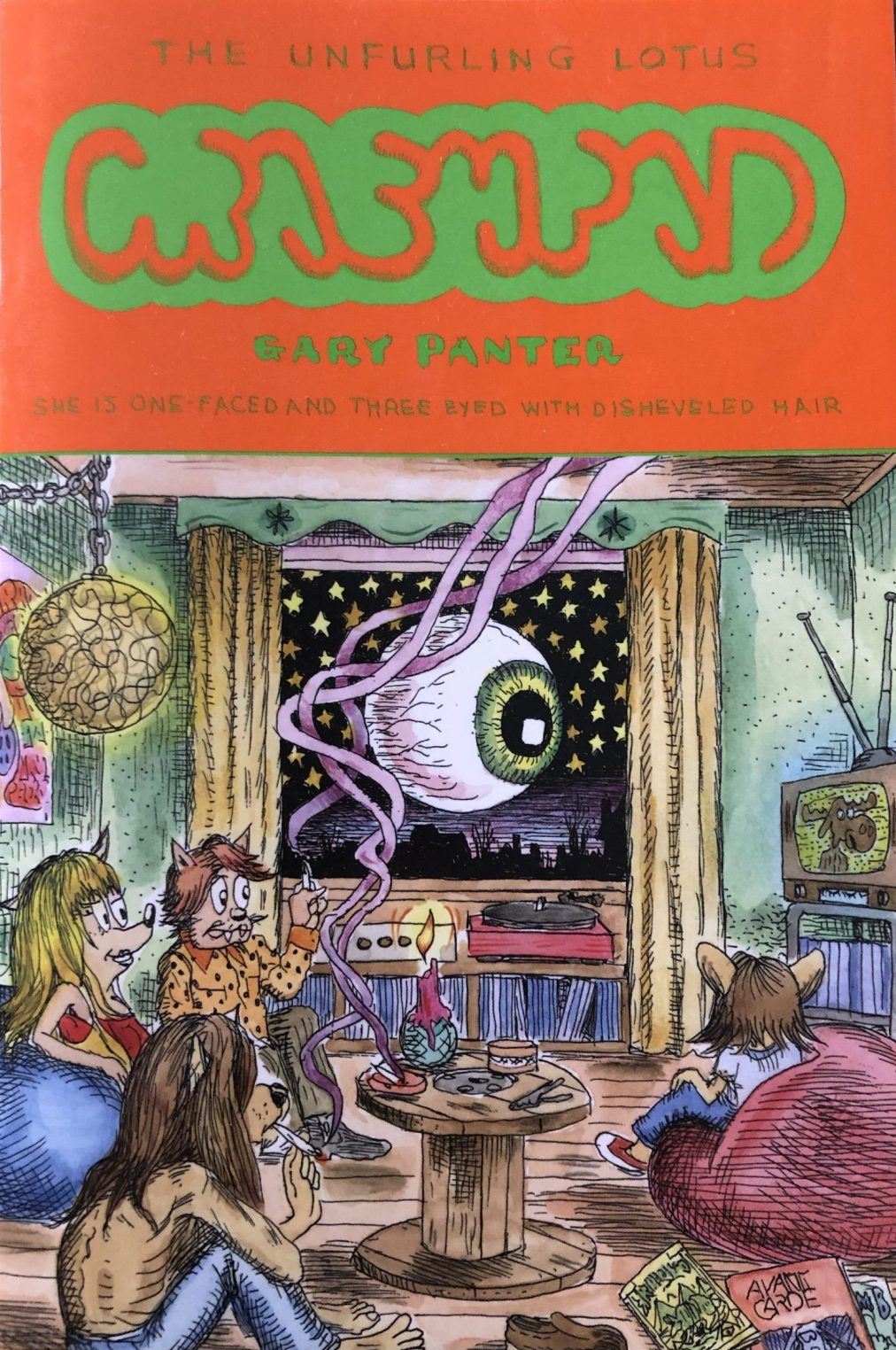

What you made of Crashpad depended on the form you saw when you looked. The hardbound’s size, its paper’s quality, its end-pages mesh of ritzy orange and royal blue, its glittery gold-on-orange cover provided a solidity, a volume, a value, which the comic lacked.4 Book became more than “book.” It became objet d'art, into which incorporation stripped the comic of funny book worthlessness (well, worth-$5.99-ness) and alchemized it into part of an esteemed whole. The composite assumed the aspect of construct: Rauschenberg’s tire-encircling-goat become book-enclosing-comic.5 Goshkin had an awareness of contemporary cartoonists spiritedly tearing down the comic/fine art wall. Narrative was to scratch heads over. Panels provided the eye-mind engagement of oils on canvas. As post-tonal classical music and free jazz brushed shoulders, comic shops and museums leaned toward each other. But the comic–just the comic–was what he had been asked to review.

Its front cover displayed its title in rock-poster-like dissolving electric green upon an orange ground, a semblance of letters which a brain must make whole. “The Unfurling Lotus” ran clearly above that and “She is one-faced and three eyed with disheveled hair” below. Is the lotus “she”? Goshkin asked himself. Why does “one” take a hyphen but “three” not? He sensed there would be no answers. Which may be, he also sensed, the point.

Its front cover displayed its title in rock-poster-like dissolving electric green upon an orange ground, a semblance of letters which a brain must make whole. “The Unfurling Lotus” ran clearly above that and “She is one-faced and three eyed with disheveled hair” below. Is the lotus “she”? Goshkin asked himself. Why does “one” take a hyphen but “three” not? He sensed there would be no answers. Which may be, he also sensed, the point.

Pictured in full-color below the words were four anthropomorphic hippies (cats and dogs) seated on beanbag chairs or floor around a wood spool-table, candle-dripping, smoke from three joints rising, Bullwinkle on TV. Outside, amidst a field of stars, a gigantic eyeball floated. What was that “eye”? Adornment? Detail? God observing his creations squandering their time?

It was the ‘60s.

That much was clear.

Goshkin had lived through them - and certainly preferred them to the ‘50s. But he believed that, for most of America, the ‘60s did not begin until some time between the Democratic Convention (August ‘68) and Woodstock (August ‘69). Check the films, he’d say. Compare the hair-lengths on those being beaten in Grant Park with those frolicking in Yasgur’s mud. And by the time Richie Havens had kicked off with “From the Prison”,6 Goshkin had begun losing his.

From Western Union you get messages. From me you get pictures.

-Samuel Goldwyn

Panter has called Crashpad “a meditation on the optimism and culture of the... flower-child movement,” what “worked” and what didn’t.7 Its inside covers saluted the progress toward legalized marijuana and body art, racial equality and free speech. They tipped Panter’s hat to love beads, tie-dye, black light posters, geodesic domes. The back cover paid tribute to books of the time which pointed ways toward America’s greening - beekeeping, soilless gardening, reforestation.

Goshkin had never had worn tie-dye, switched on a black light, or entered a geodesic dome. He believed the march toward free speech and equality had begun well before–and would have continued steadily apace–without input from the Age of Aquarius. He could credit flower children with pushing the country toward sex, drugs and flamboyant dress - but also two terms for Richard Nixon and a contribution to the cultural rift which still rent the country from guggle to zatch, opening it to the devourment of dukes with spoons.8

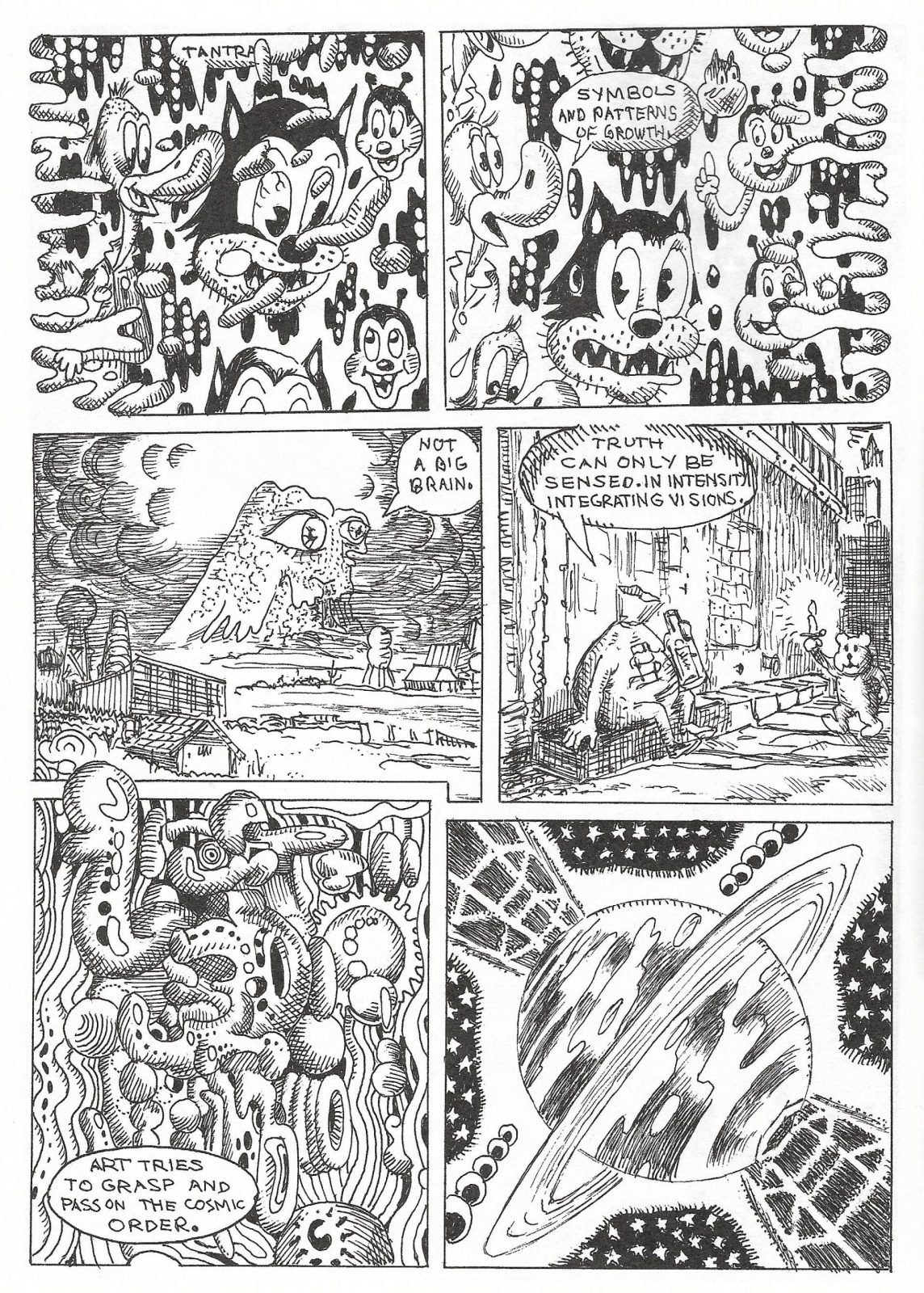

Goshkin believed Crashpad’s first story (eight pages, 36 panels) to be entitled “Balaitis”. He was uncertain because the lettering was even harder to decipher than the cover’s; and when he Googled, the closest he came to a word was “balanitis”, an affliction of uncircumcised men involving “pain, redness and foul-smelling discharge,” which didn’t seem to apply, except though a most tortuous interpretation. Whatever, it was less “story” than instruction manual.

The art, an apparent homage to Victor Moscoso and Rick Griffin, was an amalgam of black-and-white shapes and forms, from protozoa-like blobs to 1930s-ish cartoon animals. Hippies and ogres and talking money sacks and mandalas and mushrooms. A rhinoceros, three penguins, many cats, even more eyeballs, a flying saucer, a sailing ship. It seemed anything could be set down as well as anything else; but everything was kept within the limits imposed by panel lines and set amidst and in the service of the text. By themselves, the art “said” nothing. It did not “speak”, even to the extent of the action in a silent film, but functioned like a musical score, augmenting ideas, enhancing mood, driving the words before them.

And these words were–in the language of the times–“heavy”. They posited that everyone is a form “without beginning yet the beginning of all things...”, an entity simultaneously creating and destroying. Every “form”–animal, vegetable or mineral–“expresses... [its] essence”; but is created by our imagination and should not be attached to because “form is always temporal.” At one point the “story” pauses to ask “What does this... mean?” The answer is Meditation, which will “penetrate... the mystery of the universe” and allow one to “rise beyond the space/time” and exist “in total unity.”

Once he had the text, “Balaitis”’s unconnected images took on new meaning. They became a reflection of the thoughts that passed through consciousness, even when meditating. Meditating taught that these intrusions were momentary and then passed like clouds in the sky or waves in the ocean. You were what remained. You were sky/ocean. You manifested clouds/waves. You were the unity which manifested the duality.9

If Panter had led off with riffs on Moscoso and Griffin, his next stories flash-backed Gilbert Shelton. “Crashpad” (16 pages, 44 panels) set the front-covered hippies in a psychedelic-painted VW van on their way to a diner to score 2000 hits of LSD. Their dealer arrives, loud, barefoot, bush-bearded, accompanied by a Mickey Mouse-like pal, who tries to assuage the paranoia of the quartet, who’d expected someone taller, heavier and hairier, by explaining that he’d recently dieted, shaved and abandoned shoe lifts. (A great line!) Before the deal goes down, it draws the attention of Big Jim, a cowboy-hatted, cowboy-booted canine, who considers longhairs “sexual deviants, drug addicts and smart asses” and sets out after them in his pick-up. He finds the van where the hippies have stopped to trip; but they have vanished, leaving behind a swirl of protoplasmic goop. Before he can take further action, he is beamed up to a flying saucer while, from the goop, the hippies begin to emerge.

Story three, “Brashpad” (“Brasapad”?) (eight pages, 17 panels) finds the hippies at home, awaiting a pizza delivery when Big Jim bursts in - an emphatic full-page allotted his entrance. “Get your shit together!” he commands. “We have to get out there and plant a billion trees!”

“The hippies seemed to have been doing well enough on their own,” Ruth said, when Goshkin summarized Crashpad that evening. “But Big Jim required more direct intervention.” The darkening grey above the bay seemed to have decided on drizzle. If the cover’s eyeball had been God, Goshkin thought, he may have spoken through this UFO.

Same shoulder-rolling shuffle. Same sleeveless t-shirt. Same baggy shorts. Maybe even fewer teeth. Samuel used to walk into cafes, shout “DOWN GOES FRAZIER! like garbage trucks unloading, frightening the horses. Goshkin had not seen him in years. “How you doing?” he said.

“Been fuckin’ up Putin.” Samuel looked Goshkin over. He had an open Coors in one hand. “Oooz the greatest boxer of all time?”

“Muhammad Ali.”

“Nachhh.”

“Sugar Ray Robinson.”

“Nummer two.” Samuel could have dubbed Tom Waits. He bent both elbows at his sides, left arm forward, knuckles skyward.

Goshkin retrieved the picture. “Jack Johnson.”

“Ooo uz Jess Willard?”

“He maybe beat Johnson.”

“Koo-ba.” Samuel shielded both eyes from the sun like Johnson on the canvas in Havana. Did he gargle with ground walnuts? “Dook white women cross state lines.”

Goshkin felt his spirits lift. He reached for his wallet.

Samuel gave him a fist to bump.

Hope is a thing without teeth too.

“Art tries to grasp and pass on the cosmic order,” Panter writes in Crashpad. Fifteen years earlier, he had said he was not a “communicator” but an “experimenter.”10 During the years of his new book’s creation (2017-2019), Donald Trump had taken office; North Korea and Iraq had increased nuclear capacities; global temperatures had risen near a point of no return. We might not have enough time, Goshkin thought, to worry about artificial intelligence developing to where it could do us in.11

Panter was now 70. If he had acquired wisdom, it must have seemed time to share it. And the “cosmic order” he hoped to “pass on” seemed to coalesce around installing a sense of one-ness. Man-with-Man. Man-with-Earth. Man-with-Cosmos. It appeared that, given present circumstances, the purpose of the oneness was to keep man from destroying his planet. If you wanted to save the planet, creating a comic book might not have been the first thing to come to mind, but, Goshkin would concede, adding one grain of sand to the dam against rising oceans could not hurt. And from the days of flower-power, Panter had mapped three paths away from raging fires, poisoned waters and acid-dripping skies: Meditation; LSD; and alien intervention.

Based on personal observations, Goshkin thought tripping more likely to lead to locking yourself in a bathroom trying to flush a foot down the toilet than to satori. And Buddhists had been meditating for 2500 years without it dissuading them from butchering the Rohingya. As for flying saucers bailing Earth out, taking 66 million years of history into account, a life-destroying giant asteroid seemed more likely.

As a piece of art, Ozark had hit him harder. In the name of family, Marty and Wendy Byrde had killed and killed and killed. In the climactic scene of the final episode, an ex-cop tells them he has the goods. They will not rise, as they had planned, to Koch and Kennedy-level. Then their teenage son appears holding a rifle. The screen goes black as he fires. Goshkin had thought it unfair to link Kennedys and Kochs. Then he had accepted it. Families craving wealth and power were families craving wealth and power and families led to tribes and tribes led to nations and it was all us against them.

On a cardio-walk through the neighborhood, Goshkin had struck up a conversation with an elderly–even more elderly–man working in his front yard. When the man said he was a retired professor of philosophy, Goshkin recommended a novel whose central character was Ludwig Wittgenstein. The professor recommended in turn two non-fiction books about 20th century European philosophers, pre-WWII. Goshkin, who had struggled to a C- in Philo I, a course he had taken only because (a) he was now in college where that seemed a thing to do and (b) he had read most of the Hum I book list, at least in Classic Comics form, ordered both.

Devoting this portion of his Golden Years to “Truth” appealed.

* * *

- See, Elizabeth Kolbert. “Testing the Waters.” The New Yorker. April 18, 2022.

- Most cartoonists about whom Goshkin had written would not have known Duchamp from his snow shovel. Panter knew him and those he influenced.

- Mike Kelley. “Gary Panter in Los Angeles.” Gary Panter. Vol. 1. Dan Nadel, ed. (2008).

- The comic’s cover is reproduced in full color on the hardback’s title page. Its interior and back covers appear in black and white at the hardback’s end.

- In an Artforum interview by Hillary Chute, Panter explained that since the market for “art comic books... [has become] a fetish market... making a fancy book with a lowly book inside” was the way for him to “address” the issues he wanted.

- Or “Minstrel From Gault”, accounts differ.

- Chute op. cit.

- See, Thurber. The 13 Clocks.

- The ideas expressed in this paragraph come courtesy of Ira Reid, a retired North Jersey attorney, well-read in Buddhism, with whom Goshkin had bonded over their shared open heart surgeries and medically induced comas, experiences which had affected both more deeply and more positively than either might have expected.

- Todd Hignite. In the Studio. (2006)

- See, Steven Johnson. “The Writing on the Wall.” The New York Times Magazine. April 17, 2022.