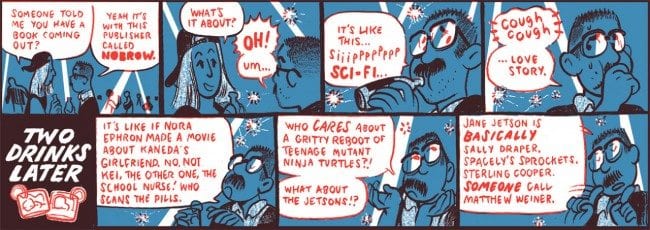

Nobrow debuted Jeremy Sorese’s first graphic novel, the sci-fi story Curveball, at Comic Arts Brooklyn. Curveball follows Avery, a young genderqueer person who works as a waiter on a cruise ship off of a science-fiction version of Chicago’s tourist-y Navy Pier. Avery pines after Cristophe, a sailor boy, and Avery’s friends and co-workers try to convince them that Christophe’s not worth the heartache. Jeremy garnered fans for the sinuous visuals, bold colors, and emotional frankness in his illustrations, comics, and sketches. He also writes the ongoing Steven Universe comic book for Boom!, drawn by Coleman Engle. I talked with Jeremy over Skype about troubled crushes, technology, and perspective.

Nobrow debuted Jeremy Sorese’s first graphic novel, the sci-fi story Curveball, at Comic Arts Brooklyn. Curveball follows Avery, a young genderqueer person who works as a waiter on a cruise ship off of a science-fiction version of Chicago’s tourist-y Navy Pier. Avery pines after Cristophe, a sailor boy, and Avery’s friends and co-workers try to convince them that Christophe’s not worth the heartache. Jeremy garnered fans for the sinuous visuals, bold colors, and emotional frankness in his illustrations, comics, and sketches. He also writes the ongoing Steven Universe comic book for Boom!, drawn by Coleman Engle. I talked with Jeremy over Skype about troubled crushes, technology, and perspective.

Interview conducted by Annie Mok, transcribed by Lucy Betz, and edited by A.M. & J.S.

ANNIE MOK: How are you doing?

JEREMY SORESE: I’m good! Super busy, but good. This morning I just accepted a job at MICA, so I have a lot of paperwork to fill out.

MOK: I guess New York people travel to MICA once a week [to teach]?

SORESE: Yeah, I’m going to be the king of the quiet car on Mondays and Tuesdays.

MOK: [laughs] What are you going to teach?

SORESE: I’m teaching character design and a “drawing on a tablet” class.

MOK: Have you taught before?

SORESE: I taught a little in Chicago, in a comics class at [the comic book store] Challengers Comics. But not anything substantial. I’ve done some lectures in classrooms and I really loved it. I spoke at my friend Hannah K. Lee’s Parsons class back in September and that was so lovely!

MOK: I remember a long time ago you said that you were looking forward to a future time when you would quit New York and live out in a quieter place and teach. Is that your long-term plan?

SORESE: I would love to go out to the country one day, that’s the ultimate Maurice Sendak dream. I just renewed my lease in New York for another year, so I’m here till at least next November.

MOK: Let’s talk about the stuff leading up to Curveball. When I met you [at the Toronto Comics Arts Fest 2011], you debuted the first—was it 16 pages?

SORESE: I don’t know, I don’t even have a copy of that mini comic anymore. That’s gone to the four winds.

MOK: I don’t know if it had the same title, but it was a mini with a screen printed cover. We both had stories in the Little Heart 2D Cloud anthology [that debuted at TCAF], and it’s interesting to see "Love Me Forever! Oh! Oh! Oh!", your story from Little Heart, in contrast with the stylistic changes later on. You were starting on a path to this super stylized approach to comics, with strong colors and angles. The story was a memoir story about your parents getting married, and you thinking about marriage and wanting a boyfriend—and then Curveball is about this protagonist who has been through the wringer with relationships.

MOK: I don’t know if it had the same title, but it was a mini with a screen printed cover. We both had stories in the Little Heart 2D Cloud anthology [that debuted at TCAF], and it’s interesting to see "Love Me Forever! Oh! Oh! Oh!", your story from Little Heart, in contrast with the stylistic changes later on. You were starting on a path to this super stylized approach to comics, with strong colors and angles. The story was a memoir story about your parents getting married, and you thinking about marriage and wanting a boyfriend—and then Curveball is about this protagonist who has been through the wringer with relationships.

SORESE: Yeah! It’s funny too, because I just finished up a week of journal comics for The Comics Journal…. there should be a better way to say that than that. [Mok laughs.] But that feels like some strange continuation of that Little Heart story, because it’s in the wake of equal marriage rights, and coming to terms with all of that, and seeing my opinions changing as I get older. I always forget that I’ve been making comics for, at this point, eight years. You forget there’s a accrued knowledge of who you are that everyone has of you. “Oh yeah! I’ve been putting this stuff out there for so long.” So it’s, of course this all fits together, of course there’s this heartbreak sonata that I’ve been slowly composing.

MOK: [laughs] Well, I heard this before, and I really agree with it: that there’s a starkly different sense of memory that occurs when you draw or write, and I think most people don’t really remember their work. I know that when I look back on old work, I’ve completely forgotten it, it’s fresh. How do you see your opinions of that change over time since that story in 2011?

SORESE: Yeah, I was 22 when I started that story. You mean in terms of equal marriage rights and all that?

SORESE: Yeah, I was 22 when I started that story. You mean in terms of equal marriage rights and all that?

MOK: [laughs] I assume you still think that equal marriage rights is a good thing. You haven’t come around! [They both laugh.] You just mentioned your opinions changing between then and now, looking at the difference between the diary comics you’re making now, and then.

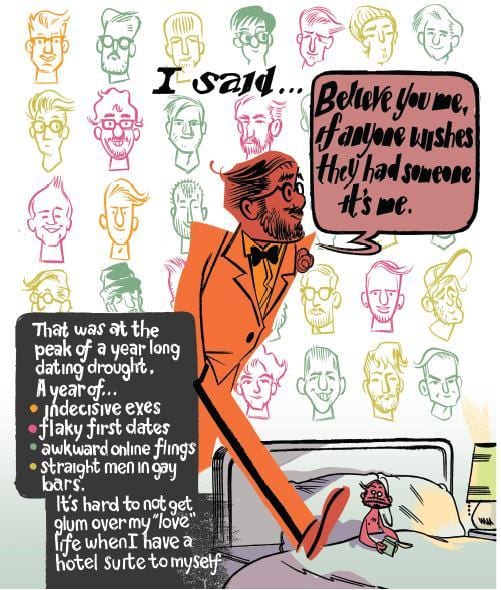

SORESE: It’s that funny thing of having a place where you can see your maturity levels change, or the way you view relationships, which are such a large portion of our lives. To see that opinion evolve, but also that all the things I thought were so important or embarrassing to me, now don’t matter in the same way. That Little Heart story is about being so lonely, and wanting completion through relationships. The journal comics I just put out are coming to terms with… Not that [relationships are] not important, but that it doesn’t change anything. I remember at that time, making [“Love Me Forever”] and feeling so vulnerable. Now the things I make… I’m pushing myself in the same way and I don’t feel vulnerable at all. For example, in that TCJ comic, there’s one where I openly talk about having a threesome, which is new… I was not that kind of person, I would not openly talk about that. But now, of course, I’m more willing to open up about th. It doesn’t freak me out in the same way it used to.

MOK: I remember my impression of you [in 2011 at TCAF]. I was, of course, this ridiculously cartoonish sex fiend at the time—and being in Toronto and trying poppers for the first time… [Sorese laughs.] God, that’s a silly drug. But I remember standing next to you and saying, “Oh, isn’t that guy hot?”, and you were like, “Mmhm...” [They both laugh] And I was like, “Oh, disapproving! I’m a little scrappy here!”

SORESE: I found a photo of that class I was teaching at in Chicago at Challenger’s Comics, and I was like, arms crossed, sweater vest, so uncomfortable. Then there’s this photo Hannah took of me at Parsons in September, and my hip is cocked, I’m wearing a fancy collared shirt. A completely different person. I’m sure I’ll have the same conversation in ten years when I reflect back on what I’m working on now, but it is a very nice benefit, to keep anything as a mile marker.

MOK: So that was 2011, and I saw the piece “A Reminder” from 2012, which was interesting because you dedicated it “for Sophie”—which, I don’t know who that is and I don’t need to know—but my first thought was that it reminded me so much of Sphincter, the Sophia Foster-Dimino comic, which is also a first-person narration comic that’s about using a building for a metaphor or a series of metaphors, about letting people in, and how we show ourselves to the world. Then there’s this comic “Tender Tinder in Need of a Match” from 2013, which is interesting because there’s explicit sex in it. It made me realize that in Curveball and your other work, I haven’t seen explicit sex, there’s only suggestions towards it. Was that a conscious intent, to keep Curveball semi-clean?

SORESE: I think I wanted to make an unsexy book. A lot of it was reflecting back on my earlier twenties, and despite the fact that I was having sex at that time, I feel like it wasn’t quite “adult” sex. There were definitely remnants of childhood, and that’s the thing too, that the comics I’m working on now are pushing into this area of being about more explicit sex. Curveball is definitely not a sexy time in anyone’s life.

MOK: Curveball is set in the future, and its protagonist Avery is pining over Christophe, this sailor boy that they like and used to have some kind of a relationship with. Everyone around Avery is kind of nurse-maiding them. When you talk about this age… it seemed strange to me that everyone was catering to Avery and really checking in on them about their heartbreak, because Avery’s pining. I was like, oh, what age is Avery? Their friends, housemates and coworkers are a little older than them, and they’re concerned that Avery is making a mess of theirself. Can you talk about that place in your life, or in Avery’s life?

SORESE: It’s the first attachment in life, where you don’t have the skill set yet that you build up over time from other relationships to rationalize what you’re going through and what you’re feeling. It’s not teenagery, because it’s a first taste that is more substantial than teenagery, the phase where people are like, “This is my soulmate, this is where we’re going to get married, we’re so lucky, I found someone.” And you’re a tiny baby, but you just have to go through that time in your life, and everybody can tell you that it’s going to get better or easier or you’ll meet someone better, and you won’t even care about this person in five or six years. You can’t know that until you actually do it. Avery knows better, and they’re very aware that that they know better, but they can’t emotionally feel that yet, and they have to go through the paces. So the book is a lesson in that, seeing someone have to painfully drag it out of them and then move on.

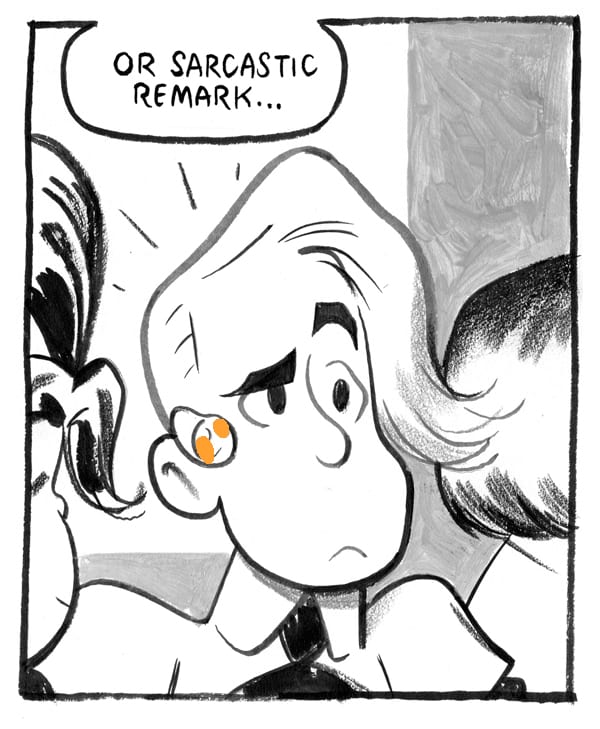

MOK: This “unsexy” thing makes a lot of sense, because there’s a part in which Jacqueline, Avery’s friend and housemate, says to Christophe, “I don’t know what they see in you.” When I read that I thought, “Yeah, I don’t know what they see in him either!” He’s kind of a jerk, and he’s also not drawn sexy. He’s got a Moomin-y kind of face, and his head is a complete circle, and his nose is also almost a complete circle. You get the sense of Avery pining over someone not worth their time. Who seems cartoonishly jerky.

MOK: This “unsexy” thing makes a lot of sense, because there’s a part in which Jacqueline, Avery’s friend and housemate, says to Christophe, “I don’t know what they see in you.” When I read that I thought, “Yeah, I don’t know what they see in him either!” He’s kind of a jerk, and he’s also not drawn sexy. He’s got a Moomin-y kind of face, and his head is a complete circle, and his nose is also almost a complete circle. You get the sense of Avery pining over someone not worth their time. Who seems cartoonishly jerky.

SORESE: I haven’t read many reviews yes, because it’s still early, but so far everyone’s said that he’s an adult Charlie Brown! Which was not intentional on my part, but it made me think that there is an emotional unavailability, or that Christophe’s features—he’s not fully there. Going back to the whole not making a sexy book, it felt so strange to try to tap into… That’s a problem I’m facing now, making more comics that are… sexy for lack of a better word, is that it’s so subjective, attractiveness in a drawn cartoon character. The way that I draw is already so goofy, and maybe it’s a vocabulary I don’t want; I don’t want beefcake-y people, I don’t want to perpetuate the idea that that is what sexy is supposed to be.

MOK: I mean, I think Avery is cute. I mean, Avery is one of my types. [Sorese laughs] Avery’s cartooned, but they have less Muppet-y proportions, and your drawing is very solid, so I think something that does lend itself to being sexy in the work is the real tactile nature of the figures, which you miss in a lot of comics, especially in “indie” comics. There’s a lot of attention to shadows and lighting, and the planes of the figures, that give them this weight. Can you talk about that physical weightiness? Are there any particular influences you can point to where you were developing that?

SORESE: I was talking to someone not to long ago about that sort of indie comic style of, not simplicity, but approaching it from almost a short story point of view. There’s like, a man, in a t-shirt, generic, and you can very quickly describe him and move on. I was saying how, for me, that’s really frustrating; yes, I know comics read really fast and you don’t have the time to visually develop someone in three dimensions, but there is something about having a tactile quality. I always think of it as like an action figure. As a kid, you bonded to a toy, and it’s that specificity that I’m always trying to find, that you can do so much with, even though indie comics is not into that. And I don’t know why. When I went to SCAD, I noticed—which really bummed me out—this delineation between indie cartoonists, people who were manga influenced, and superhero people, and none of them would ever cross paths. It was also very gendered. You would be in a critique and someone would reference someone or something—it’s not that that they hadn’t read it, it’s that they would pretend they didn’t know what it was, as sort of party lines. That tactile quality is something I love so much in manga and anime, that this is not only a character in the story, but that you could market and turn it into something that’s larger where it stands on it’s own. Which allows you to bond, hopefully, to the story in a more personal way than “generic man with t-shirt and particular haircut.”

MOK: Was there a particular manga that you were looking at?

SORESE: Earlier on it was more manga influence, so, for example, Avery was very much an attempt at making a dopey [Ghost in the Shell creator] Masamune Shirow character. I actually just dug up old character designs. Avery, at one point, had a lot of floopier hair parts, and sort of the sci fi babe on the motorcycle—sort of a Bulma [of Akira Toriyama’s Dragon Ball], Masamune Shirow moment. That stuff was a really big influence. I was also pulling from sci fi worlds that felt really macho, and trying to make something that was not macho at all. Dragon Ball’s soft, but it’s still very macho. I was trying to go for something that had all that fun and had these cool things, but it wasn’t about the cool things, it was hopefully more emotionally resonant ideas than “This is a sweet robot design!”

MOK: That makes me think about Sendak, who you brought up earlier and who I know is a hero of yours. This comic [title of yours] Goldy, Over There, which makes me think of Outside Over There, the Sendak book. I was wondering if that was a direct pull.

SORESE: Not really, I think maybe subliminally.

MOK: What does Sendak , and the [2009 Lance Bangs/Spike Jonze] documentary Tell Them Anything You Want: A Portrait of Maurice Sendak mean to you? [Jeremy had recommended the documentary to me in January 2013.]

SORESE: When I was a kid I was really obsessed with Where The Wild Things Are, and when I was coming to terms with my homosexuality—that feels really dramatic to say, sorry!

MOK: The word “homosexuality” makes things sound dramatic.

SORESE: Yeah. The realization of that in my life was just a very late realization, and it was the same time that he publicly came out.

MOK: Oh really! When was this?

SORESE: I just packed it up—I still have the article printed out of when he came out, from The New York Times. It must have been 2008. I was starting my junior year of college.

MOK: Was it something he had mentioned casually, or was it a big announcement?

SORESE: I mean, he was with his partner for 50+ years, so it was like, the best kept secret, but it was never mentioned publicly. It was after his partner had just passed away, and he was talking about a book he just put out, the name of which I can’t remember right now, and at the end they were asking him, “Is anything you haven’t told everybody?” He was like, “Oh yeah, I’m gay!” [laughs] At that moment, I think it was like was having… ‘cause there are so few gay role models across the board, role models that were great not because they’re gay but because they were just great people, and made great work that I’m attached to, and I feel like Maurice just became bonded to me. And of course, on top of that he was just an amazing illustrator and not only that, a great person. That Spike Jonze documentary, I watch almost every six months, and I just cry my eyes out. It’s like being aware of A: How lucky my life is, and that I get to be the person I am, and B: have a recording of someone who is being very emotionally honest, which I think so many of us struggle with. It’s a byproduct of him being at the end of his life and losing his partner, and being able to have nothing to lose. But I’m so grateful for that, and have that reflect back on this work that I already loved before having any of the pressure of him being a gay man.

MOK: That’s interesting that you say “the pressure of being a gay man”, because that’s something I think about a lot, or I used to. This thing that you brought up, that “he’s not just great because because he is gay and he’s out, but he’s just a great person and a great artist who is out.” Is that something that was important to you at a certain time, or still is, this kind of distinction between people who are known primarily for their sexuality or queer identity, and people who are known as artists first?

SORESE: Um, I don’t now, I think it mostly comes out of the fact that there are so few that it’s hard to get choosy. And, you know, with the gay media that we get, which, I can’t talk for all queer media, but at least the gay material from or about gay men in any context is always garbage.

MOK: Yes, there’s a lot of bad, bad media about gay people. That is classically true.

SORESE: Yeah. So I think for me, having a space and having a person who made great work, and also was gay, it’s sort of like a slam dunk, it feels like. Instead of having to parse out, “they have great politics or they’re trying really hard, but this story sucked, or this TV show is garbage.” That’s the thing too with gay men, where they bond to women, because there’s a longer tradition of better stories written by women, and better stories written about women, that they become the placeholder for things that we emotionally bond to. So when it’s something good actually by a gay man, it’s exciting.

MOK: Were you doing journal comics before starting Curveball?

SORESE: No, I think the Little Heart story was the first journal comic ever, not in history, but in my personal life. I definitely was not a person willing to divulge that sort of stuff for a very long time. Especially in comics I was making in college, they were very goofy and not emotional in the way I’m trying to be emotional now. I don’t think that was something I could have done.

MOK: That’s interesting because goofiness is such a key component to the character designs and the design of the world. To have the goofy things balanced with that kind of sweet emotionality makes this great soup. There’s so much anthropomorphized in this version of the future: Jacqueline goes to get coffee at a machine called “A Cup of Joe” that has a face sticking out of a giant coffee cup, like “Kilroy was here”. [Sorese laughs] I’m curious if you were kind of thinking about isolation in regards to technology. The robot guard looks like character actor-y old man from a ‘forties movie. Were you thinking about our desire to connect and technology taking the place of that in some regards?

SORESE: That was sort of by happenstance. Back in 2012, a friend of mine was reading the first chunk of pages that I ended up scrapping, and they made a comment about that false positivity that ended up becoming a big part of the book. Putting on a brave face, and how that’s really hollow. It became a thing of like, when you’re talking to your toaster. Even talking to anything that can’t answer back to you, and how that becomes a crutch. It can seem really cute at the time too. I talk to my roommate’s cat all the time and it’s a running joke, but the cat can’t understand, and I’m talking to myself with the cat as the placeholder. So the world, and the way I was thinking about it, became this sort of anonymous hug from the world around you, saying, “It’s gonna be okay!”, and how fake that actually is.

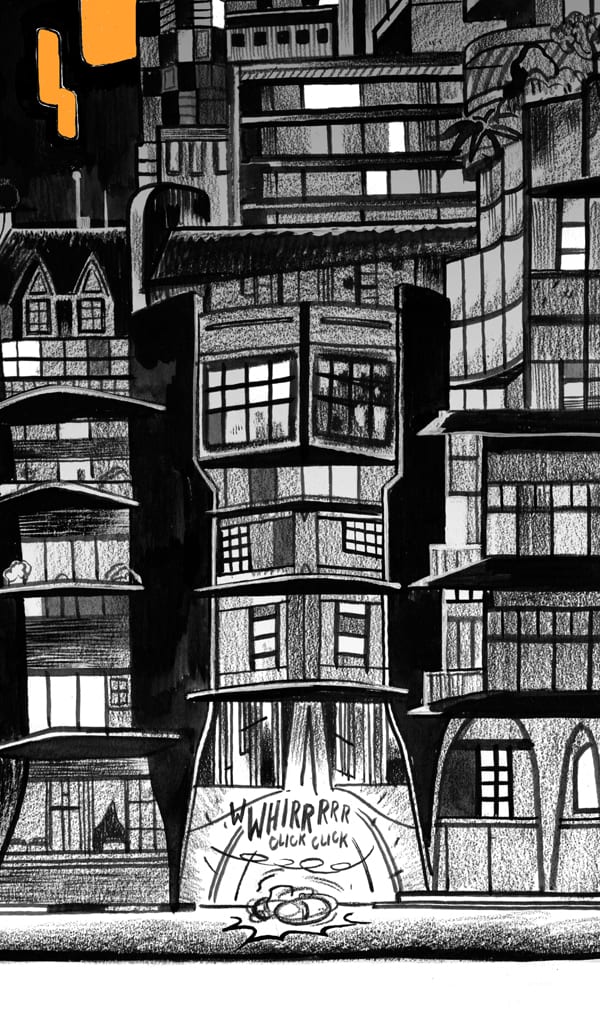

MOK: [laughs] I think of talking to the cat is a little bit real because you and the cat do have some relationship, whereas you and your cellphone don’t. [both laugh] And there’s all this stuff about interactions with technology. There’s this orange spot color as a margin in the book, and there’s an orange spot color running through [in the art] that represents everything electrical, computer-based or technological, while everything else is in black and white. One of those things that’s orange is this kind of Google Glass-style earpiece that Avery wears that connects to messages. And because it’s with them in every single panel. You get this sense of technology following them. What was your thought process in regards to looking at the deep inextricability we have with technology at this point?

SORESE: It sort of just became stress, the idea that you’re never allowed to be away from it, especially with relationships, regardless of whether they are romantic, or whatever, it’s just part of the way we relate to each other. That the option to reach out is always there. To have Christophe be removed from the grid was an added stress of wanting to but not being able to. It’s always on your mind, 24/7.

MOK: Christophe is a sailor, and he’s off doing his work. When he finally comes back, he communicates in code with a piece of paper, which is shocking to Avery and Jacqueline. Jacqueline says something like, “Where do you even get a piece of paper anymore?” Then they later, in the book, talk about this machine, this curveball machine, which is a decoder. It seems almost like a toy decoder, in the way it’s presented. What drew you to this connection between relationships and deciphering a code that holds this kind of promise, and this fear, of what it might mean?

MOK: Christophe is a sailor, and he’s off doing his work. When he finally comes back, he communicates in code with a piece of paper, which is shocking to Avery and Jacqueline. Jacqueline says something like, “Where do you even get a piece of paper anymore?” Then they later, in the book, talk about this machine, this curveball machine, which is a decoder. It seems almost like a toy decoder, in the way it’s presented. What drew you to this connection between relationships and deciphering a code that holds this kind of promise, and this fear, of what it might mean?

SORESE: The letter-writing thing became this idea from taking the classic romantic tropes, and especially with this story in which it’s about a person at shore and their love that’s a sailor, to sort of take that tongue in cheek Greek Tragedy.

MOK: And a gay trope too! For him to be a sailor. [laughs]

SORESE: [laughs] That’s a thing I didn’t quite realize until halfway through the book, like, oh, I’m a gay man, of course this is what I’m drawn to. Another big influence on the book was Jane Austen novels. There was something that I loved so much when I first read Pride and Prejudice in college was that so much of that book is waiting for letters. You write a letter and wait three days for it to get delivered, and then they write a letter. Just painful, in the most literal sense of that word. So for me, taking this sci-fi story, and liking that idea so much and just finding a way to fit it together and allowing it to be as cheesy… and hopefully to break through the cheesiness and make something better through it. That idea that it doesn’t matter how easy it is communicate with with each other, how “accessible” it should be, it’s all elaborate code. And especially when you’re in that moment of being obsessed with someone and you don’t know how to articulate it, and you’re waiting and you don’t know what to do with yourself, everything is like an Illuminati-level cipher. All the times I’ve ever let a crush borrow a book from me, and the times I’ve assumed that there’d be a message somewhere in the book… just the most cheesy part of yourself that is convinced that they’re not only thinking about you in the same way that you’re thinking about them, but also as psychotic about it as you are. [Mok laughs] So the story and the code-messaging came out of that. specially if you are dating someone or in love with someone who is emotionally unavailable, like Christophe is, there are layers that you have to try to peel back. You think that you can do it, that you can ride it out and figure out where they are coming from, but of course it’s a puzzle you will never figure out, that’s the point of it.

MOK: What drew you to that sense of melodrama and cheesiness?

MOK: What drew you to that sense of melodrama and cheesiness?

SORESE: [laughs] The things I was really influenced by, storytelling-wise, especially when I first started the book, I was really obsessed with old movies. My mom got a Tivo when I was in high school, and I just Tivo-ed everything.

MOK: Which old movies? You’re talking to the right girl.

SORESE: [laughs] Things like The Philadelphia Story. I was obsessed with anything by Billy Wilder. I will be obsessed with Billy Wilder for the rest of my life. The Apartment, for example, is a huge influence on this book, and so that sort of jokey, tongue-in-cheek, pun-y elaborate joke setups. For many Billy Wilder movies, especially later on, getting really intense in terms of the subject matter, like alcoholism or depression, suicide. Things like that having this slow burn, where you’re being tricked for like an hour and ten minutes into thinking, “This is a really fun movie!” Then of course something horrible happens, and everybody’s trying to pick up the pieces, especially since the protagonists in Billy Wilder movies are pitiful optimists. Even when things fall apart around them, they’re still like, “Well, we have to keep going!” I think that stuff is really ingrained in the things I’m drawn to. It just came out really easily.

MOK: I think of Marilyn Monroe’s character, Sugar Kane, in Some Like It Hot, her optimism in her character is so sweet and relatable, but also so unbelievably sad, in the way that she [feels] beaten down by men who are unreliable, and then throws herself into a relationship that, at the end of the movie, hopefully will change, is the optimistic part.

SORESE: The one review I have so far [of Curveball] compared anything that happens on the boat to a Groucho Marx movie, which, I hadn’t thought about a Groucho Marx movie in so long, but I was like “Oh my god! Of course!” I was obsessed with those back in college. Your influences are just in there, and you don’t even realize you’re regurgitating this stuff forever.

MOK: Well that’s one thing that’s so interesting to me about this book. Having interviewed Liz Suburbia previously, and talking to her about Sacred Heart, which is another first major, giant work, and both of you siphoning through so many different influences. When you mention The Philadelphia Story, that’s interesting to me to think of because, having looked at that movie in particular and a couple others for this workshop I did recently, and showing it to the students, there’s something about those old movies that have such a strong visual sense. Strong silhouettes and shadows, and the character relationships are depicted through the visuals, where they stand in relation to each other, that is missing in a lot of modern films, and certainly in a lot of modern comics. Are there visual throughlines that you saw throughout the book, particularly in terms of character relationships, which are so essential? There’s the way that technology really overtakes by the end of the book, or merges. At the very beginning the orange is very sporadic, and then the spot color completely overwhelms the characters in certain climax sections near the end. How did you design that, or come to that?

SORESE: The way the energy was depicted visually, where I was coming from with it was, like, shojo manga sparkle. That was the start, and then I was sort of like, how can I make this design element literal. Like, how can I make it a story point. Because, you know, the way I see it in my mind when it’s in a three-dimensional object is like glittery dust. When enough of them get together they form a three-dimensional shape. I guess the Shoujo sparkle is an emotional resonance made into a design, and I was like, how can I make this design a plot point and also an emotional point of the story.

MOK: We’re talking about an incident that happens in this universe where there is a “spark,” which is this event where technology overflows and it’s protected against by the society and really watched for so it doesn’t happen, but they see it happen a few times, where the spark overtakes a building or a mass of people. Can you talk about that idea of overwhelming, and making that overwhelming visualized?

MOK: We’re talking about an incident that happens in this universe where there is a “spark,” which is this event where technology overflows and it’s protected against by the society and really watched for so it doesn’t happen, but they see it happen a few times, where the spark overtakes a building or a mass of people. Can you talk about that idea of overwhelming, and making that overwhelming visualized?

SORESE: For me, it was that the technology has the good and the bad. It destroys but it’s also the building block that holds everything, so it’s how they rebuild structures, and how they fix things, through the same process backwards. So, I wanted it visually to be something that stood out, but felt very in contrast to the gloomy gray tones of the whole book.

MOK: One of the climaxes that sparks this issue—pun there! [Sorese laughs]—is that Avery listens to a mix CD, and it’s this outdated technology that melts. It’s Avery’s feelings that kind of overwhelm everything and then make that technology unstable. Can you talk about the relationship between attaching your feelings to technology, and the dynamic that creates? There’s also a part where Avery is looking through their messages from Christophe, and the messages come up through this earpiece that they have, and then they appear in front of them, and they surround Avery, and then Avery take the messages and drags them to a trash bin and delete them. So there’s this running theme through the book of technology, particularly in regards to memories and communication encircling you, and this thing of a relationship to technology that becomes this placeholder.

SORESE: It became a compare and contrast between technology as sort of this… not getting anything emotionally substantial out of technology, like, for example, saving text messages. Wanting something so badly but not having anything substantial, so you hold onto whatever you can get. Also, the other contrast being, for example, the letter writing, which is substantial, but the stress of that. Where you have this thing and, like the mixtape, it’s a substantial, real object, and not knowing what to do with it. When you’re with someone or trying to be with someone and it’s not working, and they’re distant in every sense of the word, you need any kernel to hold onto. It should be like, “Yeah, I got the letter,” of course it makes sense that I’m substantial in this person’s eyes, but of course it never works like that, and it becomes more stress because it’s just a placeholder .Everything in the world being made out of this synthetic material, and being more easily synthesized energy-wise, it’s sort of all Marshmallow Fluff. So, even though the building is substantial, and people live their whole lives in it, that stuff can go away and come back and nothing has any permanence.

MOK: This thing you said about Marshmallow Fluff reminds me of coming back to this thing about goofiness. There’s a throughline in this book about Avery’s laughter. Early on, Jacqueline says, “Oh my God, you laugh like Christophe laughs,” and it’s represented visually. Throughout, characters are cracking jokes with each other, trying to endear themselves to one another, and also annoying one another with jokes. Can you talk about this? You see it in so few comics and so few stories, characters trying to egg each other on. Can you talk about developing these relationships?

SORESE: Going back to Billy Wilder, what I’ve always loved in Billy Wilder movies, people have jokes and inside jokes with one another that are not funny. [Mok laughs] You can sort of see why people are laughing, but they’re such elaborate in-jokes, but they end up explaining so much more about these characters that I love so much, which is the way we speak to each other anyway. I didn’t want it to feel like people were playing to the audience, where they’re like, “I am so funny!” And no, no one is actually that funny. [Mok laughs] We’re funny because we know each other, and we have a rapport, and we get where each person is coming from. So the humor was this idea of that, but also when you’re in a rough time in your life and you’re trying to put on a brave face, there’s the false-jokey quality that, well at least I put it on. This sort of plucky, overcompensating for however you’re feeling inside. You’re deflecting your own life. How everybody’s ensuring to everybody that, “Yeah, I’m good, because I’m laughing right now.” But actually I’m pretty bummed out.

MOK: Yeah! The whole thing seems to take place in Chicago, or some version of Chicago.

SORESE: [laughs] Yeah, very Chicago-y.

MOK: It was of course potent for me, because we both lived in Chicago at the same time, although we didn’t know each other then. Can you talk about Chicago as a kind of memory city?

SORESE: Chicago in general, or Chicago for me?

MOK: Chicago for you, as a city holding memories and transforming it in this way, where you’re making this dream version of Chicago.

SORESE: [laughs] Yeah, it’s this very idyllic Chicago. Avery and Jacqueline’s apartment is very much the Chicago apartment, with the courtyard and the gate. It’s where I started making the book, so it has the very literal sense of being the first city I have ever lived in. My understanding of how cities work was very flavored by Chicago’s goofiness. But then there will be other parts of the book that are sci-fi versions of cities I was living in while I was working on the book. There’s a scene from the end that is very much Paris, and then there’s a scene where Avery has an incident on their bike, and that’s very much sci-fi Berlin. It’s already this Jeremyverse, this Jeremy Universe inside my head, finding places that felt lived-in and understood by the way I see it, as a sort of intimacy. Like, I’m familiar with this, and this is a city I know, these are places I’ve been, I can vouch for it, therefore I want to put it in a book. It’s a thing of trust for the reader. Chicago is very much, you know, Navy Pier, and the suburbs, and quietly biking at night, because no one is out and it’s Chicago and everyone is in bed by ten. All that stuff was a big part of how I wanted the book to feel. Going back to the action figure idea, being this substantial thing, you can go into it, touch it, and are better for having read it, because you can feel it, instead of just being like, this is a cardboard town that’s erected purely for the story.

MOK: You mentioned living in Paris and in Berlin. You were on an Angoulême residency? Was that during the middle of making this story?

MOK: You mentioned living in Paris and in Berlin. You were on an Angoulême residency? Was that during the middle of making this story?

SORESE: Yes, technically the middle. I went there in fall 2012, and I’d had 150 pages of the book penciled. I threw them all out. I’d gotten a really intense critique from Jessica Abel that was amazing, but it was, “This book is a mess! You should refigure this out!”

MOK: This was at the residency?

SORESE: Yeah, I gave her the PDF and we had lunch, and I will never forget it because I didn’t eat while she just blew cannonballs through my whole story. She just ate and digested, and was having a really nice meal, just being like, “Your story is a mess, you have to start it over.” So I stopped it and started other projects and came back to it.

MOK: What were the wrong turns you were making [with the story]?

SORESE: I was just a baby starting my first book, so there was a lot of things I was not fully thinking through. Especially because the way in which Jessica and I approach sci-fi—because she’s also a sci-fi author—is very, very different. So having someone who approaches it from a very scientific, very analytical way, in a way I’m not approaching it, clued me into the things that were a mess because I didn’t really think about it. Like, larger societal things, about race, or about gender, in a way that I was like, “This is a thing I just want to draw!” and she was like, “Well, you have to think about these things, there’s reasons for these things to be in your story, and you have to tell me why.” So having that critique was good for me, because that’s the thing about sci fi, it’s so hard to… When you do sci-fi, you can’t divorce it from societal stresses, racism, gender… it’s kind of inherent to the story. That’s why I’m going to be doing more sci-fi, and that’s why I’m excited about sci-fi, because it is a good place to talk about things larger than yourself, just because you have to. I feel like in fantasy, you can get away with so much more, because fantasy is already built into this world of lords and knights and there’s already a hierarchy in place that you can plug into and you don’t have to really think about. But sci-fi, because it’s not too distant from our own lives, every decision you make is substantial. And I just wasn’t thinking about it in that way.

MOK: I was curious about the place of oppression in the universe you created is, because aside from the fact that capitalism still exists, and you have this boss man character, who is listed on the list of characters on the belly band as being “Boss Man”— [Sorese laughs] —I didn’t get a clear sense of the place of racism in this universe, and the place of gender within this universe. Avery, of course, is genderqueer, they are referred to as “Mx.” and as “they.” I didn’t get a clear sense of what that meant in terms of social hierarchy, besides maybe a couple of small mentions. I was also curious if Avery was assigned male at birth or assigned female at birth, and whether that still had similar connotations in this universe as it does, as I understand, within our current day.

SORESE: Well, for me the story is not dystopian, it’s utopian. It’s about that thing I think we all do where people are like, “Oh it’s fine, we’re good now.” How could I construct a world where, the problems are there, but everyone is very much smiling through them, so it’s not so much a problem because we’re not saying it’s a problem. The same way that Avery’s relationship with Christophe works, where they’re saying that they’re fine when they actually aren’t fine, and they sort of ignore it until the problems are really in their face. I very much wanted the story to be about obliviousness, so that… there’s violence towards the end, and bad stuff comes to the surface at the very, very end. But the critique is sort of that ostrich in the sand, but there’s no solution for it and there’s no critique on things that we should be doing better. The same thing for race and gender, coming from the same place of being like, well, no one’s got any beef with any of it, so it’s not a thing that’s drawing attention to itself, it’s just… “We’re good.” It’s that thing, especially being in a queer community where you surround yourself with like-minded people, and you’re like, “Oh, we’re great!”. You’re in this little bubble, and you’re not aware of the larger things beyond your front door. I’m working on a short story now that is very much about life outside of the city…

MOK: Oh, in the same universe?

SORESE: Yeah.

MOK: Oh, great!

SORESE: Yeah, my next book is also set up in the Jeremy-verse.

MOK: Oh, that’s great!

SORESE: Which is why I’m excited to delve into larger things, and tiptoe into things like what suburbia means, what the countryside means, and what it means living in the city, and be very calculated about that. So I think, you know, there’s a ton for me to talk about with racism and gender hierarchy and all that, but Curveball was generally not that kind of story. Curveball’s like that point in your life where you’re, like, 22 and optimistic and super oblivious.

MOK: If you come from a very privileged background, like we have.

SORESE: Yeah. So the book is very much reflective on that same time in my life, like, these are the lessons that I’m learning now, and now is when I can talk about these lessons.

MOK: Can you talk about your approach to designing pages and your use of materials? There’s a wonderful layering of values and value hierarchies that you don’t see in many other comics that maybe have more traditional or staid layerings of blacks, whites, and grays, within a black-and-white comic.

SORESE: Well, I really wanted to get away from that sci fi dead-line Moebius, so that was the first thing. Like, nope, I’ve got to use colored pencil, I’ve got to make it a little more clumsy, or at least attempt to make it clumsy. Using actual materials not only to contrast the sort of energy burst pantone decision, but also to give the world weight.

MOK: There’s a luminousness to the pages. Light is extremely important.

SORESE: It’s that thing too, of my influences from old Hollywood black-and-white movies, that Vaseline on the lens, that theatricality that I really wanted the story to have. There’s actually an Italian comic by Manuele Fior, about an alien crashing to Earth, he’s a huge influence on me. His book came out in the middle of me making Curveball, and I was like, “Damnit!” His is very much coming from the same place of subtle sci-fi that is hinting at larger societal problems but isn’t addressing them head-on because it’s not that kind of story, and because the characters are oblivious as well. He’s using charcoal and watercolor pencil and making this soft, delicate story about this aging couple going through a rough time. I feel very much akin to that book, this sort of space, finding sci fi that was very warm and inviting, very much bottom-up storytelling instead of top-down. Like, I don’t want to care about the Trade Federation, I don’t want to know how spice is made, I don’t want to know any of that stuff. I just want to know what music they’re listening to, if they had a good day.

MOK: One thing I’m curious to ask about is, in all your stories that I’m aware of, there’s a dedication, which I love. I do that with my work sometimes, and I really enjoy seeing that in other people’s work. Curveball is dedicated for Dave, John and Molly. “Pups in Peril,” your Adventure Time short is for Jon Chad, the cartoonist. “Give Us Back Our Beemo,” also an Adventure Time story is “for Benicio,” and Goldie, Over There is dedicated to your mom. What does it mean to you to dedicate a story, and to have an audience of one, or an audience of couple, in a certain way? Are you visualizing those people as your audience, and are you sending something specific to them?

SORESE: There’s a quote from Yoko Ono that’s about making your work as a gift. Since hearing that, I was like, that’s perfect. Once I make it, it’s not for me anymore. This book is huge, and I spent so much of my life working on it, and I look at copies and know it’s mine, but it doesn’t mean anything to me anymore. Someone last night told me that it’s like a death in the family: someone you’re so intimate with who is no longer a part of your life, they’re just sort of gone. It’s only memories of your time together. Which is very emo. For me, having an intended person that the book is specifically for ensures it a life beyond my time with it. It bonds it with another person, who it’s intended for beyond me. That’s the thing too, trying to make more emotional work, and trying to put myself on the table in terms of what I’m willing to talk about, being emotionally open. Even something as simple as, “I made this, I spent a million hours on it, it’s super embarrassing, and I’m in love with you enough to put your name in the book.” When I step up to the plate to make work, I want to be there and put as much of me out there as I’m willing to do. Because it’s embarrassing to make work, it’s embarrassing to put yourself out there. It’s like asking someone to go to prom over and over and over again.

MOK: When you make a work of art, and you think of it as a gift, using Curveball as an example, what is that gift? What do you hope people take from it?

SORESE: The things I make, they’re for the person I was when I started making it. Curveball is for 22-year-old Jeremy. If I could go back in time and give him that, it would be the best feeling. But that’s not possible. When I spend all these hours making comics for other people, it’s that idea of wanting to pass something back, to be like, “I learned this, and I want you to have it. I want you to benefit from all of my shittiness, all the things I’ve endured.” There’s an intimacy to it and a warmth that I love so much. Which is what I love about comics so much is that there’s no hiding. You don’t get to sugarcoat your own life or the way you work. It’s all out there in the open. The goofiness of Curveball is so indicative of the goofiness of me, so to have someone feel appreciative of all the hours I put into it is the ultimate gratification. Because the book isn’t the gratification, it’s just a stack of paper. Hopefully it transcends that, and someone feels like they know me more because of my work, in a way that knowing me as a person sometimes isn’t as clear .

MOK: Whose work affects you in the way you hope to affect people, or at the level you hope to affect people, and what do you get from their work?

SORESE: You mean in comics or in general?

MOK: In comics or in general.

SORESE: Well, coming out of a really intense Alice Munro phase, where I just read every short story this year by her. The thing about any work I really love, it’s that feeling that they’re… it feels so cheesy to say it! I’m trying to phrase it so it doesn’t make me sound like such a cheesy, sappy guy. But it’s that willingness to share your own life with someone. It’s like that cheesy dating metaphor, when you’re dating someone and they’re slowly unveiling things about their life and opening up to you. And it’s more humanizing than just getting to know someone in real life. What I love hearing from people who are just starting to make comics, especially when they’re a little bit older, is that they are so embarrassed, because there’s no separation. Everything you do is indicative of who you are. That sincerity, that you’re willing to be okay with who you are, your willingness to put yourself out there, not make joke work, or make work that’s diffusing your own life. I’m better about it now, but I had a lot of beef with fan art for so long because it felt avoidant, like you weren’t willing to talk about your own life. “Well, I can only talk about Sonic.” I’m learning that’s not the full truth of it, but I’m always so grateful for someone who is willing to talk about their own life through their work. Because when you make enough work, especially like we were talking about earlier with the journal comics, you can’t avoid the important things of your life. Like, with those journal comics, and me talking about having a threesome, it’s like, well, this happened, and it’s not a big deal. Being okay with talking about that is not something everyone is willing to do. They’re not willing to go to bat for their own life in that way.