Wrapped up with Mad

GROTH: You only got to Long Island. That's not nearly the same. The first issue of Mad, was published in October of 1952. Can you tell me what you know about how Mad came about?

ELDER: Well, it was during the Kefauver Committee, the hearings on juvenile delinquency. Of course Bill Gaines appeared and he spoke about "The Night before Christmas," which I, by the way, drew, penciled and inked. He said, "I'm going to get up there and tell them what I think." And he did. He said, "The Night before Christmas" is poking fun at Santa Claus. Santa Claus is not a religious figure. It's a phony figure. It was made up by Thomas Nast, another cartoonist. He also invented the Democratic donkey and the Republican elephant. So the committee wasn't surprised but they figured out that Gaines knew what he was talking about.

Gaines was going bankrupt really rapidly. But someone said, "Why don't we start a humor magazine or something that pokes fun at these characters that we've been advertising all of the time. Make a comic book that makes fun of the comic book." That was a very unique idea at the time. Now, it seems like it was a simple idea, but it wasn't. And it was a desperate idea, because we needed to find something that would keep us afloat. And because of that, we came up with a humor magazine that was going to be very irreverent and perhaps sell a few copies and it overwhelmed everybody. It did well. It didn't do as well as it did a few years later, but it certainly kept us afloat. And that's how Mad was born.

GROTH: You mentioned "The Night Before Christmas."

ELDER: That's correct. They thought that would be corrupting the youth.

GROTH: That was also banned in Massachusetts.

ELDER: Everything is banned in Massachusetts.

GROTH: That I didn't know.

ELDER: It has a notorious outlook on life.

GROTH: What was your relationship with Harvey at this point, in 1952?

ELDER: Well, Harvey would take me into his little room where he always took artists and discuss a story or whatever.

GROTH: At the EC offices?

ELDER: Yeah. Right down on Canal Street, somewhere around there. And he would say, "We just came up with the idea of a magazine called Mad. I think it's up your alley. If I were you, I would go put yourself into it and become an actor or become an actress, become an opera singer. Do whatever you want for yourself, but make it funny. It's got to be funny. And you can do it." He encouraged me like a football coach. Get out there and fight! That's the way I got myself wrapped up with Mad.

GROTH: There were basically four revolving artists in Mad: you, Wood, Davis and Severin.

ELDER: Johnny didn't hang around too long; he left for other pastures.

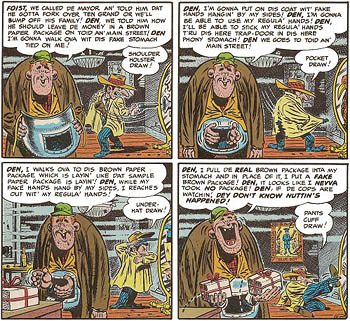

GROTH: The first strip you did for Mad was called... "Ganefs?" [Mad #1]

ELDER: Gah-niffs. It's an old German term, which means thieves. They were more or less influenced by the early comedians of physical humor. Buster Keaton. Harold Lloyd. Charlie Chaplin. You can see that in the little guy who uses violence in his humor. Always flapping the big dumbbell... What the hell's his name? I can't remember his name. Oh, it's been so long. My God, it's over 50 years.

GROTH: In the story? The character's name is Bumble.

ELDER: Hello? [Phone glitch.]

GROTH: Can you hear me?

ELDER: Sorry I woke you.

GROTH: The character, are you referring to Bumble?

ELDER: Bumble. Right. That's it.

GROTH: I want to get into some details with the stories you did for Mad. "Ganefs," for example. My understanding is that Harvey wrote the stories.

ELDER: Right, for the most part, I had a lot of freedom with Harvey at Mad. He would write the stories and give me a lot of latitude and say, "make it funny, Will." So I would say that "Ganefs" in particular and "Mole," [Mad #2] were much more from the two of us, I think I came up with "Mole" and Harvey may have come up with "Ganefs." It's hard to know who did what after all these years, but I do know that Harvey gave me a lot of freedom to do whatever I wanted on the Mad stuff.

GROTH: And he provided layouts?

ELDER: Yeah. He would roughly set it down on paper in these little panels and written dialogue and sound effects. I would work with that as a base. Basically I would use that and start throwing my things in. And he never said a word, because he figured whatever I did would only enhance the humor of what he did. And it was a good combination. It worked well. Before you know it, I was throwing in the kitchen sink and the dumbwaiter. Every blessed thing that came into my mind, which ended up in a hilarious clutter, as he put it.

GROTH: Was the lettering on the boards by the time that you started?

ELDER: It wasn't finished lettering. No. It was just the story that was being told or that was being recorded on the paper.

GROTH: When would the lettering be put on the artwork? At what stage in the process?

ELDER: After I got through with the inking. They would either paste it on, and have balloons that were pasted on ...

GROTH: Oh, really?

ELDER: Yes. Because I would try to leave room. I had to have the example of the lettering first, to see how many lines of lettering there would be so that when I made room for it eventually, it wouldn't cover up part of the pictures or part of the illustrations. I would leave a note where the balloon would go for each panel with the proper lines and size of the letters. So it wouldn't... beforehand it would be sitting in the right place in each panel, where the dialogue took place. Do I make myself unclear?

GROTH: Very precisely. I assume that many, if not all, of the details in the work are yours?

ELDER: I would say a good many of them. Yeah.

GROTH: When Harvey wrote the scripts for the stories, did he also accompany that with a description of what was going on in each panel?

ELDER: Yeah. He would reenact each scene. It was kind of peculiar and it was rather humorous. He would reenact each scene, he would tell you what every scene should have, what the situation was. His voice would change in order to express his ideas. It was fun. I would throw in a few ideas and he either rejected them or accepted them. Then I would take those ideas that I got from Harvey's re-enactment and go to town, adding as many things as I could think of to Harvey's basic layout.

GROTH: Let me ask you a specific question which you might not be able to answer because you might not remember. I wouldn't blame you a bit, but let me go ahead and give it a shot.

ELDER: I don't remember the shot.

GROTH: In the story "Dragged Net!" which ran in Mad #3, I noticed things that you've drawn in the panel that wouldn't necessarily have been indicated in the script.

ELDER: Right. Good thinking.

GROTH: I'm wondering to what extent you took the script and visualized it differently than Harvey or another artist would, and to what extent Harvey gave you directions.

ELDER: Every artist that worked for Mad had a style. Harvey knew that. He prescribed certain stories to certain artists, to one of the four of us who was best-suited to that particular story. But Harvey would reenact the story in addition to the layout so the artist had the layout and Harvey's explanation to go by. I would listen very closely to Harvey's explanations, his reenactments and I would use that to embellish the story with my own ideas. Somehow he introduced Bernie Krigstein to Mad. Bernie was certainly not, to my mind, a humorous cartoonist. His work is very serious and very well done, but I found that he wasn't suitable enough for Harvey, for Mad. He did From Here to Eternity ["From Eternity Back to Here!" Mad #12]. There were a lot of things that he could have done better, because I've seen his work. His work, some of it is beautiful. The thing is, Harvey knew exactly what could be done by what artist and how he worked. And somehow it worked. It was a very good plan. It was a good way of organizing each one of us into doing what we best do.

GROTH: EC started Panic as soon as they realized Mad caught on. You were in every issue of Panic. In fact, in later Panics, I think you had two stories in each issue.

ELDER: I wish I had it in front of me, but I'll take your word for it.

GROTH: Let me ask you how you worked with Al Feldstein vs. how you worked with Kurtzman. I assume that Feldstein also gave you the layouts?

ELDER: Feldstein was a little looser than Harvey. He relied on the artist more and gave the artist more freedom to do it on his own. He also did layouts, but they weren't tight like Harvey's and he never reenacted the story like Harvey did.

GROTH: So it was the same method.

ELDER: Yeah. They figured, what's good enough for them is good enough for themselves. [Laughter.]

GROTH: So the stories in Panic were completely written when you got them?

ELDER: No, Feldstein would leave a lot to the artist, including some of the writing. I know for Panic #1 we were under a lot of pressure to get that issue out and Al said to me, "Just do ‘Night before Christmas.'" I don't even think I had a layout on that one!

GROTH: Describe the difference between working with Harvey and working with Al.

ELDER: Uh... With Harvey, I was a little closer, because we'd known each other years back. At least, ever since we'd met in the streets of New York, and that was about ten years ago or so from that point in time. And we'd be very frank with each other. I'd suggest some ideas. He'd accept them or not accept them. He would laugh and we'd have a good time. I'd go to his house in Mount Vernon, sit on his porch and have tea or whatever we drank, Coca-Cola. It was very homey and very homespun and we were very open with each other. Feldstein I didn't know that well. I knew him, of course. He remembered me from Music and Art. He was another Music and Art-er. And we spoke about Music-and-Art days. It was a friendly but a distant friendly. But he wasn't as hands-on as Harvey was; he wanted the work to get done and he gave some input, but he wasn't as involved with the details of the story like Harvey was. When Harvey re-enacted those scenes, the artist really knew what he was looking for. Al didn't do that, so — for me anyway — it was different. I wasn't always sure what Al was looking for, but he seemed to like what I did.

GROTH: Did you detect a difference in Feldstein's approach to humor?

ELDER: Yeah. It wasn't classic enough for me. To me the challenge was something classic, something that had an intelligence behind it — an intelligent thought. It was like... I'm trying to make a comparison here to something I've seen. It's like Chaplin compared to a Laurel and Hardy. Chaplin was physical, but with an idea behind it. Laurel and Hardy were not exactly physical. They were physical, but I wouldn't call them physical artists. They were endearing characters, someone you would have loved to have known as a friend. So to me the lot of them are comedians, but at the same time their approach to any problem is slightly different, given their characters.

GROTH: You did "Starchy" in Mad #12.

ELDER: Oh yeah. There were a lot of letters on "Starchy."

GROTH: Which was actually remarkable. It seemed to me to be the most risqué strip that Madpublished up to that time. You had Starchy smoking —

ELDER: All the things that are wrong with people in society registered on those pages.

GROTH: You had the principal chasing Betty and Veronica around.

ELDER: Well, it happens. Some teachers prey on their students.

GROTH: Right. But it was pretty unheard of to put that in a comic in 1954.

ELDER: Yeah. But I feel my zaniness is based on truth. If it weren't that way it would be pretentious. It wouldn't be believed at all; all really great comedy is based on truth.

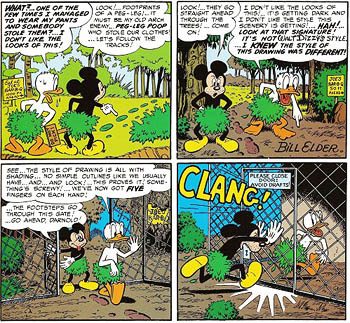

GROTH: How are you able to capture the likenesses and the artistic styles of these strips? I'm thinking of "Starchy" and the Li'l Abner —

ELDER: I worked like a b-a-s-t-a-r-d. I worked very hard, because not only was I challenged to do something interesting, very interesting, but also to show Harvey that he's got a guy whose doing hard work for him and myself. I was really out to please him, because he never knew I could do that many characters, and accurately. Of course, when I say accurately it was them during those days. They changed during the latter part of their careers. People forget that. When you do a caricature of anybody like that — like Hirschfeld, the Line King, you know, he drew pictures of people in the theatre who aren't recognizable in their last days on Earth. They've changed. So you're apt to be criticized for the fact that it looks like them but many years later.

GROTH: When you started off at Mad, your first four stories were crime satires. They were "Ganefs!" "Mole!" "Dragged Net!" and "Shadow!" [Mad #1-4]

ELDER: Well, it's like the old Hollywood days. They'd come out with films that were pretty much all alike. Westerns for a time dominated the screen. Everybody loved them until the darn things wore off. Gangster movies were very, very famous, very popular in the later '20s and the early '30s. You had Cagney and Bogart, Edward G. Robinson. Then you had the romantic comedies with Cary Grant and Katherine Hepburn and that sort of thing. So it changed with the audience and the times.

GROTH: Right. Then you did a couple of horror satires: "Outer Sanctum!" and "Ping Pong!" [Mad #5 and 6]

ELDER: Well, you have to try something new.

GROTH: Then you started to do character satires like "Shermlock Shomes." [Mad #7] One of the things that I liked most in your stories was, for example in the Holmes satire, suddenly toward the end bubbles are coming out of his pipe and Dr. Watson is holding up an umbrella. Would that sort of invention have just been a spontaneous decision on your part?

ELDER: Probably so, because it had nothing to do with the story.

GROTH: It had nothing to do with the story or the dialogue. It just pops up out of nowhere.

ELDER: Harvey, when we went on these conventions, would answer questions from the audience and from the fans in general, and would tell them that he never knew what I was going to come up with. He laughed at everything, Harvey. If you laugh at something, you're more or less forgiving them.

GROTH: I think the fact that it simply pops up for no reason makes it even funnier.

ELDER: Yeah. It's like the Marx Brothers. They would do something anti-social out of nowhere.

GROTH: Like a series of non sequiturs.

ELDER: It's also battering the social divides to hell, such as people who are very rich and very mannered as opposed to those who are starving to work for a buck. Harvey would say, everybody will be reading Will's sight gags and not even read my stories. Everyone laughed and I expected them to laugh because the whole thing was ludicrous.

GROTH: Do you, among the strips you did for Mad and Panic, have any favorite genres that you worked in or any types of strips that you preferred?

ELDER: In Mad I liked the newspaper-comics and radio parodies. Those were the things I knew the best and I had always made fun of them when I was in school, so it came very naturally to me. Harvey knew that. I would have to say that the radio — "Dragged Net!" and "Outer Sanctum!" — and, of course, the newspaper funnies — "Poopeye!" [Mad #21], "Mickey Rodent!" [Mad #19], "Tick Dracy!" [Panic #5] — jeeze, that list just goes on and on. It's hard for me to pick one; I like them all. There are things I like about all of them, but I can't say I have a favorite. It's like asking a parent which child is his favorite; you just can't do it... out loud!