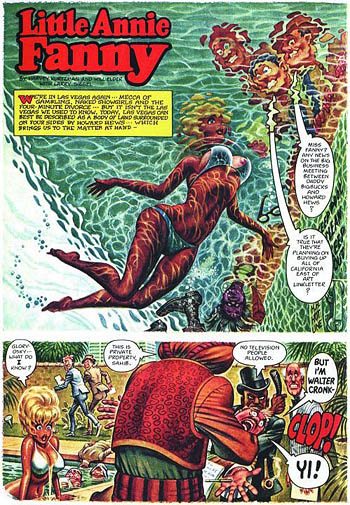

Little Annie Fanny

GROTH: You've seen the two big volumes of Little Annie Fanny, of course.

ELDER: Yes. I was sent one.

GROTH: I read all of that. I wanted to know if you could sort of put yourself back in 1962 and tell me what you know about how Kurtzman and Hefner got together on Annie Fanny and how you were brought in. What were you doing prior to Little Annie Fanny? Was the work that you were doing for Help! enough to pay the bills?

ELDER: No. Not where I lived. Taxes went up suddenly, drastically. I had to go confront that sort of thing.

GROTH: Right, because you weren't doing a tremendous amount of work in Help!

ELDER: I was, and I was trying to get all I possibly could, the more the better. I figured people would get to know me and often. [Excuses himself to take a phone call.]

MRS. ELDER: Gary?

GROTH: Yes?

MRS. ELDER: OK. We're back.

ELDER: Nosy neighbors. They're very good. You need the neighbors, around here. Otherwise you grow old alone. What were you saying?

GROTH: You were doing work for Help! and Kurtzman was on salary there as an editor. But you weren't on salary; you were still freelancing.

ELDER: That's right.

GROTH: Now, I know that you also did work for Pageant.

ELDER: Oh, yes. I did quite a number of works.

GROTH: And I'm not sure if that was the same time you were doing work for Help! in the early '60s; I think Pageant was the late '50s, though it could have spilled over into the '60s.

ELDER: Well, yeah. I think you're absolutely right. The thing is, there were some stories I'd rather not have illustrated, just because anyone can do them. The surface of the moon or deep-sea diving for some kind of mining. But when it came to humor I was right there. I loved what I did.

GROTH: You were first and foremost a humorist.

ELDER: Yeah. I was doing some stories on Christmas cards, all of the different renditions of Christmas cards: the homemade kind, the very classy kind like a Rembrandt painting. But there's a theme running through all of them, which showed that it was not the real stuff. It was something kind of fictitious and ridiculous.

GROTH: Can you tell me a little about Pageant?

ELDER: Pageant was like Coronet. It was one of these handy magazines. You could hold it in one hand. And it covered all sorts of things, like People magazine today. The latest movies, the latest shenanigans of a movie star, that sort of thing.

GROTH: And you would illustrate articles.

ELDER: Yeah, I would do that. If there was a story attached to it, I would do some lead-ins, leading illustrations.

GROTH: After Humbug, one thing I'm curious about is why you didn't go into doing more comic books — go into DC Comics or one of the other companies and try to get a job?

ELDER: Because I knew a lot of people in the trade by this time. Or at least they knew me. And they offered me all kinds of things. But I like the humor and you had a lot of humor in the later cartoon comic books. To me, it suited my tastes moreso. As long as there was work, I was able to get that sort of genre.

GROTH: How did you get the Pageant gig? That lasted for a few years, I think.

ELDER: Well, Harvey had worked there and he recommended me. I went up there one day and showed them my work and they asked me for an example of my ideas. They were very pleased, and they offered me the first story and that's how it began.

GROTH: I have to ask you about something called Hateful Thoughts.

ELDER: Oh yeah. This was an early cartoon book. Black and white. There were some very funny things in it. The ape at the end of the book, that's what I remember the most.

GROTH: Yes. The back cover.

ELDER: It's an ape or a Neanderthal. Did you ever see the Neanderthal I did where the guy is chipping out a message on a stone? Do you remember that one?

GROTH: Yes.

ELDER: That was the epitome of the Ice Age or the aftermath of the Ice Age.

GROTH: So how did this book come about?

ELDER: I kept looking for work. I went from door to door, and I figured I'd better go to a publishing company that puts out comic books or comic art. And sure enough, Citadel was one of those companies. I dropped by the offices and the editor told me he had something up my alley. He said, "Come around next week." I couldn't find other work during the week because I knew I was going to get something at the end of the week. And the guy kept his word. A miracle.

GROTH: So basically this was just a commission job. They gave you the manuscript and you did the drawings?

ELDER: Right. It kept me in the business.

GROTH: I was surprised to learn that you actually did work for Cracked.

ELDER: Yes. That was in the early days of Cracked.

GROTH: That's right. 1959.

ELDER: Yeah. It was fun. Severin was an old buddy of mine. We worked together on many things penciling and inking, as you know. This was something that they needed at Cracked.

GROTH: And you did a cover as well.

ELDER: Yeah, with Brigitte Bardot.

GROTH: Right. So your memory's good.

ELDER: Thank God!

GROTH: In the '50s, when you were looking for work, you were knocking on doors and you were working for Cracked and Pageant and so forth, did you consider calling up Gaines and going back to Mad?

ELDER: I got a call from Al Feldstein. Al offered me all kinds of things — to sleep with his wife...

GROTH: Which I assume you did.

ELDER: Yeah, I didn't mean it, Al, wherever you are. He would laugh. That's the kind of guy he is. I like Al. I think he's a very bright guy. He deserves more credit than he's getting. Just because he took over institutions, people hate the people who take over the institution. They don't realize that if it wasn't for them, the institution wouldn't be around! That's what happened to Mad magazine. There's 50 years of it. Don't forget that for a moment. That guy kept it alive. As much as I thought Harvey was tremendous, one of the best, Al shouldn't be pointed out as an interloper. Nothing could be further from the truth.

GROTH: So after Humbug, why didn't you go back to Mad? Do you remember?

ELDER: Because that would have meant that I was leaving Playboy and I was starting to build a career at Playboy. If Annie Fanny didn't work I would have other work to do. So that was too appealing, too appetizing for me to turn down.

GROTH: But how about after Humbug and before Playboy. It sounds like you were kind of scrambling for work between magazines. Have you ever thought about what would have happened with your career in Mad if Kurtzman had continued editing it?

ELDER: I don't know. Really. I wish I had the answer to that. I don't know what would have happened. I have to be under duress before I can make any normal decision. I just don't know. It's hard to judge how you'd behave. It really is. You base your judgment on what's happening and it's not always the best thing.

GROTH: How did you segue into Little Annie Fanny?

ELDER: Well, Harvey later on expressed his ideas and opinions to me and said, "Will, there may be a book coming up soon. I hope you can become available." And I said, "Well, I have to find out what it is." He said Hefner and he had gotten together. Harvey said we'd have steady work, we'd get paid a lot better than we were; the only difference would be that we would have to stick to a code of ethics and material that is acceptable to the Playboy reader.

GROTH: Did you ever talk to Hefner before you entered into this agreement?

ELDER: No, not really. He asked Harvey who he would recommend to draw the strip, and he said, Will Elder. Hefner agreed immediately. But he didn't know who the heck to... Jack Davis, Wally Wood. They are all great artists.

GROTH: Now, Annie is essentially a female Goodman Beaver.

ELDER: Exactly.

GROTH: How did you go about designing her?

ELDER: Well, I suggested Marilyn Monroe and Brigitte Bardot. They both were cutie pies and they're very, very sensuous. A girl like Jane Russell is a little too masculine, if you ask me. There's nothing pitiful or lovely and feminine about Jane Russell. Of course, I thought very much of her looks, but the rest of her is another story. But Marilyn Monroe had that sensual innocence. She was like a sexy child. She would appeal to most anyone. In fact, she was very famous at the time. Why not work with someone who is famous?

GROTH: Right. She was at the very height of her popularity.

ELDER: I think so. Yeah. In the early '60s. '60, '61. She died in '62.

GROTH: Right. So you and Harvey must have talked about the concept of the strip,

ELDER: Yeah. I would make a few sketches in color and show them to Harvey and he'd look at them and give his opinion. And he'd say, "Can you make some suggestions?" We went over it about three or four times before we got what we liked. Or rather, I should say what Hefner liked. He was footing the bill.

GROTH: How was it decided that you would paint the strip rather than draw it with pen and ink?

ELDER: Hefner had given out freelance work to his brood of people, and I got a challenge. He said, "Give me an illustration that is realistic, but a cartoon illustration instead." That's just what I did. I did a panel of Phil Silvers in Sgt. Bilko. He's lighting a cigarette, I believe, with a toy gun. And everything is rendered very tightly and illustriously. He liked that technique. He said to do that with Little Annie Fanny, and I did and it was accepted. It was more work. I told him I was going to spend a lot of time doing these things, because they take up a lot of room. An illustration is a very slow process, unless you have a simple style, which he didn't point out at the time.

GROTH: What was your preference at the time? Did you actually prefer to paint the strip, or did you —

ELDER: I would rather have an outline and painting it semi-flat. Not entirely flat, because you have a comic book. I stuck to the realism, but in a line casement.

GROTH: I was surprised when I read the strips. I mean, the early strips were four, five, six, even seven pages long.

ELDER: That's right.

GROTH: Did you already have your painterly technique down when you started Annie Fanny?

ELDER: It developed. It hadn't fully blossomed yet. In fact, no one knew how it would develop, they would accept it for what it was at the time. But since it grew, and if you compare notes at that point, you can see the development, the change of technique — for the better, actually.

GROTH: You used tempera and watercolor.

ELDER: Watercolors and tempera where it needed it. But I used the white, blank surface of the drawing board, or illustration board in this case, to carry out my point.

GROTH: What do you mean by that, using the white of the illustration board?

ELDER: I would go over everything very lightly, more or less. In fact, Harvey would give me a rough sketch. I would refine it, redraw it, sometimes put in the color. Harvey would put in dabs of color but more or less sketchily put in colors. Not always, but some stories that were complicated. I would take it from that point and develop it a little bit more and give it a three-quarters, if you could measure it, a three-quarters adjustment to the entire strip, show it to Harv. He'd make some suggestions and say, "Go ahead and finish it." And that was the first Annie Fanny. When she's taking a bath in front of the cameras, with the screen background of a beach, and her boyfriend comes to visit her at the house, this little young kid always bringing groceries. I remember it like it was yesterday. I don't want to waste your time going over it again.

GROTH: I want you to waste your time going over it. How do you combine tempera and watercolor? When do you use one, and when do you use the other? And why do you use the two?

ELDER: Watercolor covers a broad surface with enough water and a little pigment, as much pigment as will carry the color. Tempera is an opaque medium. If you find that you've gone too heavily on a thing that should be lighter, like Annie's skin, it looked like she had a bad sunburn at one time. I used an electric eraser, because I used to erase it by hand with one of those erasing sticks that you peel away and you have a nub at the end. I bought myself an automatic erasing machine. It does a tremendous amount of work. It brings out highlights. If I put it on the paper and I want the light area to be lightened even moreso, you use the electric eraser on that spot and you have a highlight, without destroying the texture of the illustration board. You've got to get three layers. Three layers would be a good term. Three layers of illustration board laminated together would be a very solid board, because you can erase all you want and you're not going to tear up any of the surface. You have two more, three more surfaces underneath. You can blend it very lightly by holding the erasing machine very lightly so it doesn't leave any fuzz on the top. It's a technique that I just slowly learned to develop. I may sound like I'm building a V-2 rocket. But I'm not, really. It's very simple. Once you apply your style and your time and the experiments, you find you're making a very nice illustration, something that's practical. When I say practical, I mean not time-consuming because that kind of thing can consume a lot of time. The seven or eight pages that you mentioned before were pages because there was room enough for it and they were sort of an introductory set of pages. No one had ever seen this thing before and it got pretty good results. Let me think now. Some of the details are completely lost in my memory bank. That's what happens to banks today. They're closing.

GROTH: This was a pretty radical departure for you, because it was a painted comic strip.

ELDER: Not really. I used to paint portraits of movie stars just to get the feeling of how watercolors should work. It gave me pleasure to see things develop right under my nose. I did that for years. I would make my own cartoon strip and go around the town selling something. I sold a few one-panel gags. It developed slowly from Mad, and along came Harvey. I'm rushing through it because a lot of it is redundant. We would shorten the pages for the simple reason that we wanted to save time. It was taking up too much time. By shortening the number of pages we'd reach our goal.

GROTH: I noticed that virtually from the beginning of the strip that you started getting help from other artists.

ELDER: That was when we realized the pressure that was on us.

GROTH: I assume that's because you were trying to turn out more material than you could do by yourself?

ELDER: Absolutely. I was only human, and so was everybody working around me, I hope. We just had so much time to do it in. Otherwise, it only appeared three or four times a year, and that was a no-no.

GROTH: I think the first artist who helped you was Russ Heath.

ELDER: That's right. I think so.

GROTH: Did you know Russ at the time?

ELDER: Yes. Russ would come up to the Charles William Harvey studio. I met him somewhere, either there or somewhere else at a cartoon meeting, or something. I knew his work. He was good. He was very good with watercolor. A lot of cartoonists don't handle watercolors generally, like Jules Feiffer. Well, they handle brush and stain, but not really watercolor technique, where the body has three dimensions.

GROTH: I thought Heath was the artist who blended most seamlessly with you.

ELDER: Well, he was on-call when we needed him. We said, "Put everything aside, unless it's a deadline that you're working on elsewhere," and he said he'd do that. In fact, we found that a lot of fun. We were out in Chicago where Hefner had his old haunts, his old mansion. We had fun at night. We'd kibbitz and we'd go to a show at night. We'd ruminate and we'd explore the place. It was cavernous, his mansion in Chicago. We'd discuss memories and cartooning and that sort of thing.

GROTH: I thought he was the artist who adapted himself most easily to your style.

ELDER: Frank Frazetta would have been, because Frazetta was an illustrator, if you ask me. A darn good one.

GROTH: But Frazetta's work stands out. You can tell Frazetta's work within the strip, whereas Russ Heath's work sort of blends with yours.

ELDER: Well, you have to look again. Of course, I'm being very unfair.

GROTH: No, no. Go ahead.

ELDER: I see the difference. Most people don't. It doesn't matter if other people see no difference at all. That was fine. We're all happy. If it was an obligation of some kind where I had to do exactly what he did, then the technique would be gone and we would hear from Hefner. He was a stickler on mechanics and illustrations. He knew his stuff. He had some very great artists working for him.

GROTH: Jack Davis's stuff stood out. You can tell Davis's work a mile away.

ELDER: Well, his stuff is line-driven. There's always a line around it. His feet are big. His legs or knees are skinny. I think they're wonderful, but they're not in the right place.

GROTH: It was a little jarring with your style.

ELDER: Perhaps. I hadn't looked at it that way, but maybe you're right. I think the world of Davis. He's a remarkable artist.

GROTH: He's a great artist, but you two are such different stylists.

ELDER: Well, I figure maybe slightly so, in my estimation. I'm not trying to be modest. I think his work is off on his own planet.

GROTH: At the beginning of the strip, Russ Heath helped you a lot. How did that work? Did you two work in the same studio together?

ELDER: We did at times, yes. Because we were experimenting so much it was getting very costly flying out for every mistake that was made. We had a studio up in Hefner's loft. It was a gigantic place. This was in the mansion in Chicago. We'd sit there and we'd goof off occasionally. We had a lot of time, because we were right next door to the studios. We'd finish what we had to. And Hefner would look at it and we waited a half a day for him to finally get around to looking at it. It was sent back. In fact, we hardly saw him at all. Eventually we did get to see him. And when we saw him he said, "Let me point out what I like. This is what I like. This is what I don't like. This is where we can improve. This is where we should leave it alone." He was very, very efficient.

GROTH: And very hands-on. Let me skip back for a second. Where did you live at this point?

ELDER: I was living in New Jersey.

GROTH: And Harvey was in Mount Vernon, N.Y.

ELDER: That's correct.

GROTH: I don't know where Russ Heath lived.

ELDER: Neither did I, but he showed up. That was important.

GROTH: Why did you go to Chicago? In other words, why did you do some of the work in your studio at home and then some of the work in Chicago?

ELDER: Chicago was a place where we could make corrections without losing time traveling back and forth. Hefner could see the thing immediately. He was there in a second if there was an emergency. If we needed help we'd tell him about it. Sometimes we needed his help or we'd never make the deadline in time. So he agreed to that. And it was just a big, convenient time for us to do that.

GROTH: So would you fly to the mansion in Chicago to fine-tune every strip?

ELDER: Not every strip. After a time we were able to handle Annie Fanny and we would send it to Chicago already packaged and ready to be reproduced. And when the editor there, I forgot his name — they had a change of editors over so many years — he would eventually show it to Hef. Hef would then come to the studio and say, "You guys can take this home and finish it off and mail it in," because there was very little to do after all of those corrections. So it was one of those arrangements where we would need him only on very rare occasions.

GROTH: Can you remember — and I'm talking about the first few years of the strip — what Russ Heath would do and what you would do?

ELDER: I would show Russ the figures I did. There was a big orgy party and a lot of nudity running around. I know those figures were Russ's and they were good. Believe me, they were very good. They were acceptable not only by me but by Hefner and his art director. They looked like those naked balloons, the sex dolls. Their bodies were wrinkle-proof. Smooth. Nice and pink. That's Russ Heath. That's the way I saw it. What I described to you isn't a disadvantage. Do you find anything wrong with it? If I gave you those qualities?

GROTH: No.

ELDER: That's how I felt most people would react. It seemed to work because no one complained.

GROTH: Frank Frazetta worked on three strips.

ELDER: I don't remember the number, but I'll take your word for it.

GROTH: And, you can tell what he did on the strips. Did he work in your studio? Did he come over to your studio?

ELDER: He would work somewhere else. I believe he had his own studio or something.

GROTH: So for him, for example, you would do your figures and then send the board to him?

ELDER: Right. We had to find a system that worked for all of us. Otherwise, we were wasting somebody's time. I would only do the heads and hair and Annie's body, in fact. I didn't want anybody to touch Annie's body, because it should be the same everywhere. It should be consistent. That's what I aimed for. That's when you've got a lot of figures around — boyfriends, girlfriends, or nightclub people dancing. We'd pass it around and Harvey would point out the areas that should be tackled, like the heads of strange girls with fellows. They could be handled by somebody else. Arnold Roth did a few panels for a story we did on Mexico. Let's see. Who else? Al Jaffee would throw in his 15 cents. That's the way it went. That was our established technique.