Garrett Price’s White Boy, a vividly original comic strip set in the American West, appeared on the scene in 1933, shapeshifted three times in three years, and then faded into obscurity faster than a wind-blown smoke signal. Since then, a few slim sheaves of pages have been reprinted in book collections and magazines. These tantalizing excerpts have served to place a complete revival of White Boy on the want lists of many a comic art aficionado.

Garrett Price’s White Boy, a vividly original comic strip set in the American West, appeared on the scene in 1933, shapeshifted three times in three years, and then faded into obscurity faster than a wind-blown smoke signal. Since then, a few slim sheaves of pages have been reprinted in book collections and magazines. These tantalizing excerpts have served to place a complete revival of White Boy on the want lists of many a comic art aficionado.

The strip represents a high-water mark of the American newspaper comic, with striking visual storytelling that evokes the expansive beauty of the American West and the subtleties of the natural world.

I love the White Boy trilogy. It stays in my mind and touches something deep inside. It's filled with mystery and presents me with secrets in plain sight. A black-and-white pony explodes into a splashed lake of hatred and racism, while a canoe holding two young people in love silently glides through the shadows and across the panel breaks. Every element in this comic is skillfully crafted and intuitively shaped, like a proudly carved totem. The more I look, the more I see in White Boy. For me, the White Boy trilogy is capital "A" Art. The Great Spirit speaks to us across time, through the dip pen of a 1930s artist, briefly working in the funny papers.

White Boy in Skull Valley (Sunday Press, 2015)

White Boy in Skull Valley, a large, handsome volume published by Sunday Press in December 2015, collects the complete series for the first time. It is now possible to absorb the full span of the White Boy trilogy, and to understand both the brilliance and shortcomings of this extraordinary, exquisitely crafted comic strip.

White Boy in Skull Valley presents the comics in their original sizes and colors. This is a critically important feature. Like any good comic strip artist, Price designed his pages to be seen at a particular size. An accomplished painter, Price also put a great deal of inspiration and craft into designing his strip’s colors. To reprint his strip, as is often done, in a smaller size, and/or re-colored, would be to greatly reduce the artistic and historic value of the reprint project. Savoring these lovely pages in their original sizes is a world of difference. To paraphrase Mark Twain, it is the difference between lightning and a lightning bug.

The book is designed by Philippe Ghielmetti, who gives the package a bold, inviting feel. Sunday Press publisher Peter Maresca edited the book and wrote the introductory material, journeying to the American Heritage Center at the University of Wyoming in Laramie to research the Garrett Price archives that are held there. The volume includes some of Price’s New Yorker covers, rare illustrations, gag cartoons, family photos, and unpublished art.

While Sunday Press’ presentation is flawless, the comic itself is, for all the promise of its breathtaking first pages, flawed when considered as a whole. White Boy is actually three different strips, each one losing its story’s trail and ending abruptly. The three strips are: White Boy (84 pages), White Boy in Skull Valley (49 pages) and Skull Valley (20 pages).

It is barely possible that Garrett Price regarded the three strips as selected chapters in the life of Bob White. It could work like this: As a boy, Bob is adopted by the fictional Rainbow Indian Tribe in the nineteenth century American Southwest. As a young man he works for his rancher uncle, and as an adult, we glimpse him working at a dude ranch. Jarringly, the last two chapters include 1930s automobiles, making the continuity harder to sustain, because Bob’s adventures with the Rainbow Tribe appear to take place much earlier in time.

Maybe, if the strip had lasted longer, Price would have continued transforming it. A later version might have presented Bob as a married man and father on the prairie (White Man). Perhaps there would have been a final chapter in which Bob’s red hair turns white (what else?) and he becomes a determined lawman battling train robbers (Skull Valley Sheriff).

In any case, whether the three-in-one aspect of the strip was by design, or the result of an artist and syndicate trying different approaches to connect with a readership, White Boy is well worth savoring for its highly original imagery and moments of exceptional visual storytelling. At times, the strip achieves a tenderness and impressionistic effect that is rarely found in comics of any era.

White Boy (October 1, 1933 – April 21, 1935)

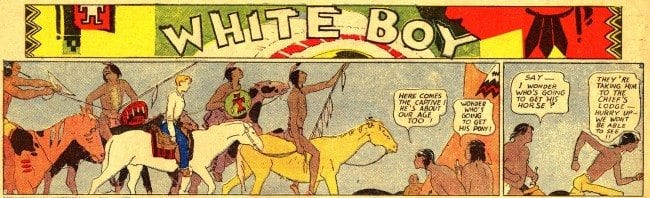

By far the most extraordinary part of the White Boy trilogy, and the basis of the strip’s claim to greatness, is the first section of 84 episodes, the ones that bear the title, White Boy. As Peter Maresca points out, “White Boy was unique in comics and in the popular culture of the time… It was a nineteenth century western from the Indian’s perspective.”

A rarity for its time, White Boy is the first comic in America to portray Indians in a sympathetic, human light. Starting in 1937, Jimmy Thompson created a series of Indian comics that also did this, most notably his long Red Eagle book in 1938, but Price’s White Boy was the first.

White Boy’s first 84 strips comprise a single continuity told entirely from within the world of the Rainbow Tribe. It’s a story about the assimilation of an outsider – a white boy – into an Indian society. Price makes no bones about the tension and conflict between the races – in fact, it’s how the story begins, with the first panel of the first page showing a Rainbow raid on a party of whites, caught helpless on a plain near the tribe’s settlement. The first panel is well-staged, with a far-away view of the slaughter, observed by three teen-aged Indians in the foreground. The series, which is told from the Indian's point of view, literally begins that way.

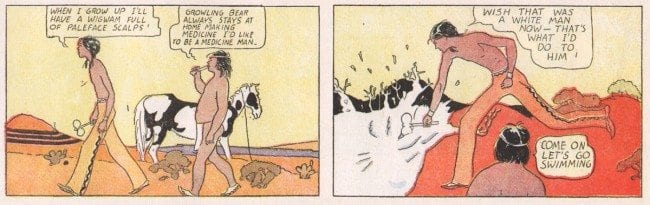

In the second panel, one of the teens, a girl speaks kindly to a dog (this is possibly a tribute to an early mentor of Price’s, John T. McCutcheon, who often included a little dog in his cartoons).

The episode’s middle tier is a conversation that reveals an immature teen’s racist animosity toward “white man.” By this point, just four panels in, we already have a strong sense of character, and a sharply delineated presentation of story from the Indian’s point of view. The second and third panels of this tier offer an astonishing graphic device as the black and white horse is visually similar to the third panel’s white water splashes shown in contrast against the black hills in the background. It looks as if the Indian teen, hitting the water with his tomahawk and saying he wishes it was a white man, is shattering the horse. This illusion only works because we are used to visual continuity between panels. By transforming the horse into a pool of attacked water, our minds are momentarily tricked into an assumption that is as incorrect as the underpinnings of racism -- it’s a stunning moment.

In the third tier, the less aggressive Woodchuck appears to hang in the air as he dives into the cool, peaceful waters. The oddness of this image, with Woodchuck’s deeply tanned buttocks in full view, signals the strip’s playfulness and humor. The teens learn that one member of the slaughtered white party survived, a white boy. In the last panel, the girl, Starlight, emerges from a teepee, saying simply, “A white boy –.” Her curiosity inspires, and reflects our own, while introducing the second theme of White Boy, an endearing pre-pubescent love across cultures.

Price’s White Boy comics have much to teach about the art of visual storytelling. The subtlety, inventiveness, and visual poetics of these comics bring them into the realm of “graphic novel” far more firmly than many modern works that bear that label.

The early episodes include a four-week story in which White Boy and Starlight are alone on a great prairie and must survive a raging, apocalyptic fire. Price’s art on these episodes ranks among his greatest work.

In the second episode, animals run wildly from the fires of doom marching behind them. There are unforgettable panels of deer, jackrabbits, and birds fleeing for their lives.

In the next week’s episode, slower, heavier herds of buffalo stampede past White Boy and Starlight. Here, Price depicts them in a way that calls to mind the ancient aboriginal rock art of the southwest. While most of the White Boy pages have 10-12 panels, for this one episode, Price designs an unusual three panel layout. The larger panels add to the sense of urgency, as time seems to speed up. The air is gritty with dust and smoke. The skies are almost black with panicked flocks of birds. White Boy and Starlight begin to realize they are going to be burned alive – and then, a single wooden match is discovered.

The last of the four prairie fire strips begins with Starlight accepting her seemingly grim fate, saying, “Ooo. It will be like torture!” As Maresca points out, Price’s dialogue for the Indian characters is natural and avoids stereotypical clichés. Price’s Indians are real people, and they speak that way. Beyond that commendable quality, Price shows he is a solid writer, able to develop character through dialogue.

The single match ignites a counter fire that creates a small safe space. It’s a powerful metaphor for good versus evil, light against dark, and life itself. The final panel of the adventure is perhaps one of the most abstract images to be found in mainstream American newspaper comics of the time. And take a close look at the speech balloons in this panel. White Boy's speech balloon looks like it is blown by the wind, as are the words. Starlight's speech balloon is vertical, protected by White Boy's -- subtly mirroring his actions to protect her.They are tiny figures in the swirl of destruction around them. It’s a transcendent image, conveying the immense, awesome majesty of a world on fire. This panel anticipates Hiroshima and Nagasaki, and the nightmares of generations of people in the not too distant future. It’s beautiful and otherworldly.

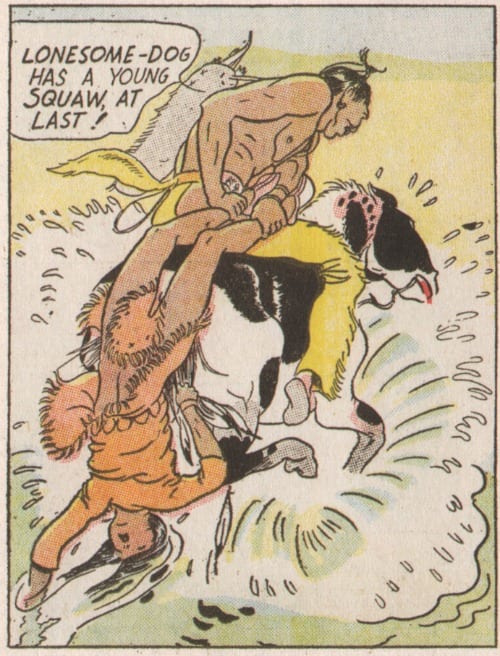

Two weeks later, we get these erotic and violent images, of White Boy and Starlight captured by vicious Sioux warriors.

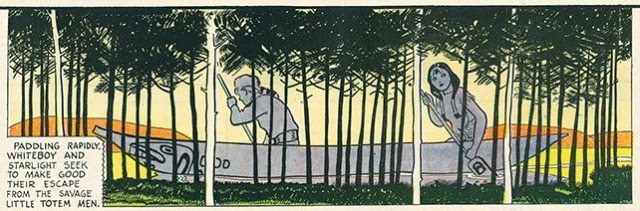

Once our hero and heroine are saved, Price creates a scene of lush, vivid beauty as our characters take refuge in a grove of trees. We can feel the coolness of the air and see the movement of shadows on the leaves.

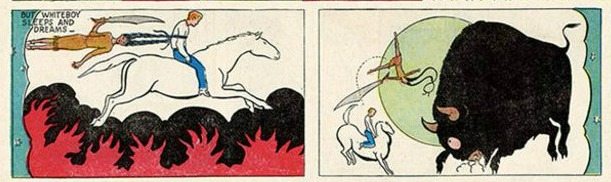

This relatively pastoral episode is followed by a wildly surreal strip in which White Boy dreams about all that has happened to him -- the deepest Price will take us into the psyche of his character.

After these first spectacular pages, White Boy’s layouts become less inventive, mostly rows of equal-sized squares, with occasional variations. This may be because Price was required to reshuffle his pages into a second version, in a different format. As with many strips of the time, White Boy was sold to its newspaper clients in two orientations: a half-page horizontal, and a full-page vertical tabloid format, known to collectors as “tabs.” The tabs were reconfigured and slightly altered versions of the half-pages, which were drawn first. Often, the tab versions included different art from the half pages.

The comics in the Sunday Press book are the half-page formats. A bonus insert sheet included in the book reprints the April 1, 1934 White Boy in tab format (also one of the few later exceptions to the mostly standardized grid layout Price adopted). Comparing the two reveals a different logo and a completely different third panel.

The practical necessity of keeping his half-page layouts modular, for easy rearrangement into the tab format very likely, and unfortunately, discouraged the creative layouts seen in Price’s initial pages.

Which is not to say the remaining strips are bereft of creativity. Price's drawings and staging are constantly surprising. He has a way of changing the angles of view so that the human forms in his panels become more and less defined, supporting the flow of the story in subtle ways. At times, his characters blend into the landscape, and at other times, they tower over it, imposing human culture on nature.

Particularly intriguing is the use of color in White Boy. Color is a visceral element that communicates on a semi-conscious level. Color is probably the first element in the comic strip to be perceived, with shape perceptions mere micro-seconds behind. Before we read the words and visual story of a comic, our minds have already absorbed the messages of the colors and shapes. If I say to you, "Tide Detergent," you very likely will think of bright oranges and yellows in concentric circles. Product packaging, an industry that pre-dates newspaper comic strips, very consciously manipulates the overall impact visual design can have on our subconscious minds with color and shape. In White Boy, Price seems conscious of this phenomenon more than most comic strip artists. Each strip has its own color palette, each panel and layout is thoughtfully designed.

Though the process of printing the strips with different presses, all over the country, inevitably leads to variations in shadings, there is a general consistency of color that suggests Price, a career painter (see part 2 of this essay, which presents other examples of Price's inventive use of color), had control over color as as design element in his comic.

There is something about White Boy that communicates on a deeper, intuitive level, and one senses at least a partial conscious design behind this. Furthermore, the range of feeling "tones" White Boy's colors, shapes, and images evoke is much broader than most comic strips of its time. In this regard, reading the strip -- and absorbing it -- is a satisfying, moving experience.

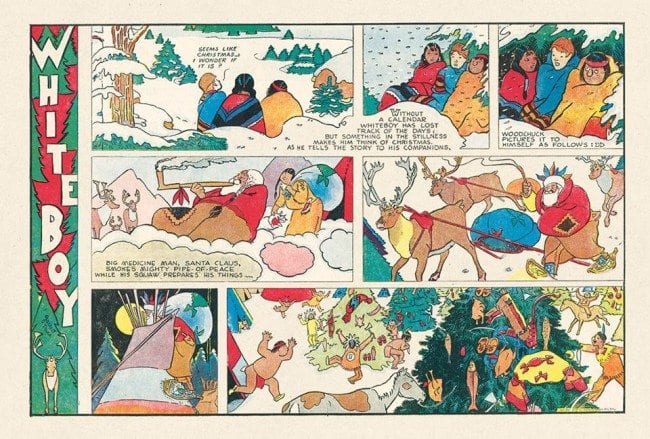

The remainder of the White Boy strips wind through a long, rich narrative. Price alternates plot developments with character-driven vignettes. There’s a particularly clever variation of the Christmas strip that was de rigueur for syndicated newspaper cartoonists of the 1930s.

In time, the Rainbow people decide to relocate and they begin a long, slow march. White Boy, Starlight, and Woodchuck are separated from the tribe and find themselves involved with a fantastical, feminine version of Joseph Conrad’s Heart of Darkness story. It is unsatisfying that White Boy and his companions never reunite with the Rainbow Tribe. Instead, they settle in with another tribe, in a totem village. The story seems to lose impetus, and the last few strips are loosely drawn, with less details.

The final strip in the first of the series’ three chapters is a stylistic shift, with tighter rendering, dark, muscular shadows, and a different narrative approach. It's as if Price is shaking his own strip by the shoulders: wake up! The last episode also marks a return to the violence and savagery shown in the first strip -- mixed with humor, and in that sense it provides a sense of closure.

White Boy in Skull Valley (April 28, 1935 – April 12, 1936)

The next week, White Boy in Skull Valley begins, without warning or explanation. Suddenly, the Indians are gone and replaced by cowboys. White Boy now has a name resonant with Indian culture, that of a bird: Bob White. We move from rifles on the prairie to pistols and Fords in the hills.

While Price’s art remains exemplary, the main story trots into a much more worn path, as Bob White grimly chases evil outlaws as though he has become an overnight star of b-westerns. There are a few interesting episodes, such as a some poetic strips involving a travelling circus (Maresca's essays reveal that Garrett Price based these strips on fond memories of enjoying a travelling circus when he was a boy in Wyoming). A continuity involving a masked man has nice art, but seems to go nowhere, veering into a sequence involving a prehistoric lost world complete with dinosaurs. The art in White Boy in Skull Valley remains so inspired that the reader may well forgive the meandering storyline.

It is hard to read the transformed strip and not mourn the loss of the sweetness between White Boy and Starlight’s innocent young romance, or the respect for an indigenous people and their culture. Despite the sad loss of an original, charming story concept, the strip continues to rank high in aesthetic value. Price’s style continues to shift in fascinating ways, and he remains interested in capturing subtle moments, like the sensuousness of diving into a warm natural spring.

Skull Valley (April 19 – August 30, 1936)

In the last third of the White Boy trilogy, the lovely, strong red-headed Nan, emerges as the central character of the strip’s last, brief incarnation: Skull Valley. The concept for this series is simple: Nan runs a dude ranch, where Bob White works.

The last chapter is played mostly for laughs, poking fun at the city slickers who come to the ranch, but it has a few deeper moments, as well. In one episode, an Apache Indian works for the dude ranch. When he grumbles over having to cater to two silly white women who have only a superficial understanding of his culture, a white cowboy tells him: “If you don’t like this country, why don’t you go back where you came from?!!”

After 20 mostly unconnected episodes, Skull Valley ends, as does Price’s involvement with comics.

On the one hand, the strip seems to plot a downward course, starting out in brilliant, spectacular fashion only to lose the trail and end with a silly, insignificant version of its original concept.

On the other hand, if one is interested in exploring the story of the American Indians and the assimilation of their lands, resources, and cultures, the strip’s course makes a little more sense. We start with a white boy adopted into an Indian tribe – and note the strip is named for that very concept, seen from the Indian's point of view: a white boy! Through the white boy's eyes, we learn about the world of the indigenous peoples of the past. Shifting time and place, the strip then explores the world of the modern (1930s) white man, filled with crime, technology, and a ruthless exploitation of nature. We end with a disguised comedy: a seemingly light-hearted comic strip which, around the gags, portrays the reversal of the strip’s original premise: Indians are absorbed into white culture.

It seems doubtful that the visual and structural intelligence of the White Boy trilogy was by grand design. There's an oddness to the story and art that suggests Price was intuitively feeling his way along, seeing where his adventure took him. The resulting atypical depictions of the American West, that vast and surreal land of myth, makes Price's single contribution to comics noteworthy.

Time spent in the world of White Boy raises a curiosity about its creator. The next Framed! column will explore the life and career of Garrett Price.