In this, the year of all things Thor, we have been treated to no end of barrel-chested, distended approaches to Jack Kirby's thunder god. The film's already-large 2D canvas got juiced in post-production and inflated into 3D spectacle, while Kirby's own take, in Marvel's reissue of Tales of Asgard, likewise got slathered over with digital sheen to render it more real-ish. A more befitting bit of Thor monumentalism was the thousand-plus page collection of Walter Simonson's run on the character: a real cinder block of a book, retouched to the artist's standards, that virtually dares you to question the “definitive” label so often applied to Simonson's Thor.

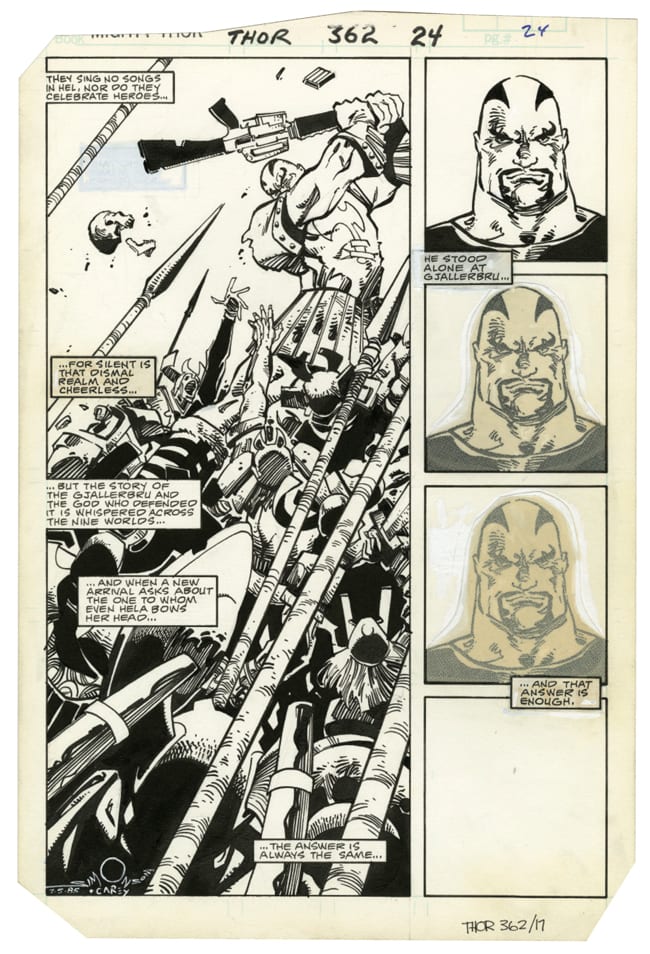

Amid all this god-sized maximalism, however, another Simonson tome arrives. The Thor Artist's Edition, from IDW publishing, reproduces seven of the cartoonist's key issues in facsimile from the original art. While it retains a monolithic scale Ol' Goldilocks would approve of—the Marvel art boards are printed at original size, so each page measures a whopping 12” x 17”—the book is still somehow minimal, stripped-down. Call it Thor... Naked. Devoid of color, with each brush stroke boldly apparent, the book doesn't give us Thor so much as it does Simonson, its large pages encouraging us to admire the clarity of his storytelling and the muted abstraction of his design.

Such reminders of Simonson's dedication to craft are always welcome. The artist took to the field in the early '70s, when industry norms of layout, character-type, and illustration style were under furious and experimental revision, thanks to like-minded young turks like The Studio and Simonson's future stablemates Jim Starlin and Howard Chaykin. 1973's Manhunter, a back-up feature in Detective Comics, would set the pace for the rest of Simonson's career: intricate yet clear page designs, a firm grounding in genre traditions beyond simply comic books (in this case, pulp adventure), and a constant interest in kicking away his protagonists' sure-footing. Oh, plus some serious knock-down, drag-out fight scenes.

Simonson would hopscotch from genre to genre in the adventurous years to follow—from pirate comics to humor to sci-fi to movie adaptations—but it is for his extended residences in various superhero universes he is most celebrated. Following the long Thor run, he would investigate other Kirby creations like X-Factor, Fantastic Four, and Orion. Lately, the artist has started more fully exploring the kind of straight-fantasy that he's been developing in hybrid form at least since Thor. Most notably, perhaps, Simonson has convincingly envisioned and inhabited Michael Moorcock's Melniboné in Elric: The Making of a Sorceror.

The interview that follows can only touch on much of this work from a decades-long career. The artist was instead gracious enough to dig deep into his Thor work once again with me, on the occasion of his Artist's Edition. But, as becomes evident while reading and thinking about that book, it can't help but launch us into discussions of other accomplishments, as well as the challenges of analog art-making, the subversiveness of comics, and the great tradition of comics storytellers, from Mézières to Mignola.

***

SEAN ROGERS: So how did the current project come about, the IDW book?

WALTER SIMONSON: Scott Dunbier, who is an editor at IDW and a very old friend, got ahold of me to see if I’d be interested in having a facsimile edition created of some of my Thor stories. This kind of full-size reproduction of original artwork is something Scott has been wanting to do for a long time. Last year, IDW came out with the Dave Stevens Rocketeer Artist’s Edition, which included all of Dave’s Rocketeer work. Scott had talked to me about it before, just the idea in general. But this time, he called me up to see if I’d be interested, assuming that he and IDW could get a negotiation with Marvel squared away that would allow IDW to publish the work. So that’s what happened, really. Of course, I didn’t deal with Marvel directly on this because, at that time, I was under contract to DC.

ROGERS: This kind of project has got to be something that’s difficult to put together, in terms of having all the original art in one place.

SIMONSON: I would imagine. It’s kind of funny, because when the news broke I saw stuff on the web where a lot of fans were excited about it, and a lot of them were going, “Wow, then we can do this, and we can do that, and I would love to see this.” And some of the stuff that they wanted--I know that artwork’s out there scattered to the four winds, and I think it would be awfully difficult to pull all those pages back together. I'm guessing there are a limited number of projects that you could do this way, where you would really have complete sets of art. I don’t know what those would be. A lot of guys in my generation and younger sold a lot of their artwork when it became available to them, and so I do think that the general idea of publishing facsimile editions is something that’s going to be a little tough to do on a broad scale. You’d have to kind of pick and choose, and you’d have to see what was available.

ROGERS: Even with the DC Absolute books that Scott was doing, it seems like the original art is more of a bonus feature than the main attraction.

SIMONSON: I think the idea behind the Absolute books was to reprint the published work in its best possible form for reading. I don’t know what kind of archives the companies have generally. In the old days it was all Photostats, which means that, if they’re good stats and they’re printed reduced size and colored and so on, they’ll come out just fine on an Absolute edition. But a facsimile edition is a little bit different. For a facsimile edition you’d really have to have the originals to shoot from.

ROGERS: Now was this standard practice at the time where the artist would be receiving the original art back? In terms of the 1983 Thor work at Marvel, that just came back to you without question ?

SIMONSON: Yeah, by ’76 or thereabouts, the companies—I believe Marvel and DC—had begun giving artwork back on a regular basis, and you didn’t have to make any special arrangements for it. By around the late '70s, I was working at Marvel, and they actually had a person on staff whose job was to return artwork, who logged in the work, who cataloged it, who got hold of the freelancers to whom it was going, and made sure it got out to them. They had a system in place to return artwork, and that’s the way it was done.

ROGERS: How do you think the IDW book showcases that original art? Obviously, the art is intended for reproduction, but you still have these original documents that are their own pieces. How does the book foreground that?

SIMONSON: Essentially, what these books are is facsimiles of the original art. I grew up in the Washington D.C. suburbs, and I remember back when I was a kid—probably no more than ten or eleven—my folks drove us around to a variety of historical sites in the area. We went, just for a couple days, down to Williamsburg and Jamestown and Yorktown, on the peninsula in Virginia. The thing I remember that’s relevant to our discussion is that I was able to buy an envelope with facsimile documents of the Declaration of Independence and the Constitution, and maybe the Bill of Rights. There were four or five documents on fake parchment. They smelled like vinegar, they were on yellowed paper, they were crinkly, and they had this feeling of age. And they were photographically reproduced from the original documents, so they were facsimiles of the originals.

It’s kind of the same thing here. The idea is, this would be as close to getting hold of the originals and seeing what they look like before they go through production, where things are cleaned up and the editorial comments are taken out. Blue lines, which you would not normally see in reproduction, are still there. Editorial comments, whatever. And of course the work isn’t colored, so it’s just in the black and white.

And in some cases—for example, in the first issue of Thor that I did [#337]—my original editor, Mark Gruenwald, had changed a line in the script, and we had a discussion about it. It was something I thought should probably stay the way it was originally, and he was game to change it back. So we had a patch put in with the original line restored, and in the original page and in the facsimile you can see the paste-up on that balloon.

A lot of the paste-ups back then were all done with paper and rubber cement, which has a lot of acid in it, so it turns the paper yellow after a while. It just kind of destroys paper eventually. So you can see the patches on the originals, you can see where people spilled coffee across the artwork. You can see the scratches where a cat laid a dead mouse across the pages.

Part of the lure, for me, is that it humanizes the artwork. I got into Marvel comics in college, and there was no organized fandom at that time so basically I knew nothing about the production of comics. As far as I was concerned, comics kind of appeared like magic on spinner racks once a month. I had never thought about the fact that somebody was slogging out midnight deadlines trying to get the art done. Once in a while there’d be an issue where it’d say, “So-and-so was ill this month, so so-and-so is stepping in to help him out.” And so I understood that people really did it, but boy, I just did not have a clue. I had no idea what the actual artwork looked like. Everybody’s more familiar now with how artwork looks—you go to conventions, there are a lot of art dealers, auction houses on the web sell originals. So you can get a better look at that stuff. But I just think it’s kind of cool to be able to see full-size facsimiles where the hand of the artist—and, to some extent, the hand of the writer—are so clearly defined.

ROGERS: You can definitely see where you’ve scratched out some things, where you’ve made little notes to the colorist in some parts.

SIMONSON: Yeah, I’m hoping I don’t have any scatological notes in there that I’m going to regret seeing in print [laughter]. I don’t make many of those, but one hopes.

(Continued)