15. Ghost Rabbit, by Dakota McFadzean. Here's my original review. This is a simple, elegant, and poetic comic about how a young girl processes the concept of death. From a promising artist with a beautiful, fluid line.

14. Kids, edited by Melissa Mendes and Jose-Luis Olivares. Here's my original review. This is another outstanding anthology in year of great ones from CCS-affiliated artists, this one featuring the editors, Chuck Forsman, Lambert, Lydia Conklin and many others telling stories from or about childhood. That hook winds up being a powerful one, as the tone of the stories ranges from fanciful to serious.

13. Too Far, edited by Joseph Lambert. Here is my original review. This is an extremely strong anthology featuring work by Lambert, Jose-Luis Olivares, Dane Martin, Alexis Frederick-Frost, and Alex Kim. They all work around the title as the theme, as various narrative ideas go "too far" in various fashions.

12. Danger Country #1, by Levon Jihanian. Here's my original review. Jihanian's clear-line style, quirky detail and unusual imagination make this one of the best of the alt-comics fantasy series. It reminds me a bit of Kaz Strzepek's Mourning Star series in terms of tone.

11. N.Y.D.I., by Jesse Reklaw. Here's my original review. Reklaw is well known as a webcartoonist and minicomics creator, and he's starting to share his wealth of experience in interesting ways. This is an instructional mini of sorts about Reklaw's experiences in self-publishing, providing some hard numbers as to how difficult this process is. The autobiographical spin he puts on the numbers and charts makes reading this a rich experience even for those who don't aspire to publish.

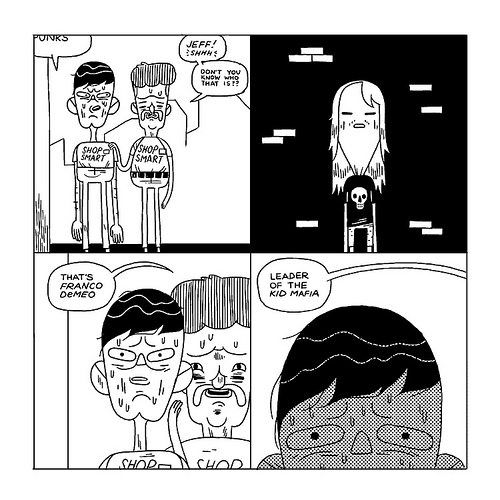

10. Kid Mafia, by Michael DeForge. The young master of fusion comics strikes again with a new series that combines Sopranos-style gangster human drama with slice-of-life teenager angst. The teardrop-shaped head, squinted eyes and long hair of the lead character, Franco DeMeo, are simply rendered but unforgettable. Throughout the course of the story, DeForge mashes together the two totally incompatible genres in a way that nonetheless make narrative and (more importantly) emotional sense. Franco is worried about finding a new consigliere because his current one is about to go off to college, but tries to shrug off his concerns by saying "whatever." DeForge ingeniously gets at the heart of the banality and humanity of its protagonists that The Sopranos was so good at; in the eyes of each of the characters, they are noble individuals--heroes in their own personal narratives. The issue ends on a cliffhanger as an impulsive fit of rage lands the Kid Mafia in some possible hot water. This has the potential to be a series with some legs, given that its source material was serialized over a long period of time, with greater emotional complexity arising because of the ways the characters were developed over time. It will be a great feat for DeForge to combine the more absurd elements of this narrative while still maintaining its ties to the humanity (and more often, inhumanity) of its characters.

9. King-Cat Comics and Stories #72, by John Porcellino. This issue is a little more fractured and free-form than recent editions of Porcellino's trendsetting autobio comic. Among other things, King-Cat has proven to be both journal of and therapy for Porcellino's battle with depression and the disillusionment of middle age. The strip "Wedding Band" features him driving and looking down at his empty ring finger, wondering "Where's my job? Where's my home? Where's my kids? Where's my wife?" The usually meditative strips of Porcellino in nature take on a far more desperate tone, as "Christmas Eve" sees Porcellino getting out of his car and taking a walk through a snow-covered forest. Whereas that would be a meditative experience in many of his strips, here he ends the strip by making the disquieting statement "I don't want to be alive anymore" but follows it up a couple of panels later by saying "But I am." It's the essence of his work, really, the ability to find ways to survive in moments of great despair. As if to leaven that heaviness, there's a lark of a story about an LSD trip he was on as a teen and some hastily-scrawled diary strips about meeting a new potential girlfriend. The issue ends with a funny story about his now-girlfriend and him dealing with a bat in their room at night and how they safely set it free. It's an understated moment of hope that avoids cliche and sentimentality. Porcellino's art is always minimalist, but there is an ease and warmth in that last story, a lightness almost, that is absent in the more painful stories he tells. In both cases, his ability to confront his own inner demons and his willingness to illustrate them forthrightly make him one of the greatest of all autobio cartoonists.

8. The Death of Elijah Lovejoy, by Noah Van Sciver. Here's my original review. This is a great-looking art object published by 2D Cloud on Zak Sally's press, and it features some of the most beautiful and confident work of Van Sciver's career. It depicts the awful details of a lynch mob hunting down the publisher of an abolitionist newspaper in pre-Civil War America, an incident that further emboldened the abolitionist movement.

7. Annotated #7, by Aaron Cockle. Here's my original review. This is Cockle's best work to date, an enigmatic story about an author who manages to apply "Edits and Revisions" to the human mind and winds up as a sort of agent for both human governments and aliens. In Cockle's stories, what is not said or shown is every bit as important as what is plainly illustrated.

6. SF #1, by Ryan Cecil Smith. Here's my original review. Fusion comics at their best, SF is a manic, sprawling and frequently ludicrous attempt at creating epic science-fiction, filtered through more influences than I can name. Smith provides sheer entertainment with a knowing nod to the audience at all times. This is a perfect match of style and content.

5. Ishi's Brain, by Eamon Espey. Here's my original review. In terms of narrative, this comic is much more straightforward than many of Espey's nightmare-logic minis, making it an excellent entry point for readers new to the artist. As always, Espey's comics inspire laughter, dread and revulsion all at the same time.

4. Sundays: Forever Changes, edited by Chuck Forsman, Alex Kim, Sean Ford, & Joseph Lambert. Here's my original review. Forsman does most of the heavy lifting in this most ambitious volume in the Sundays series. Drawing from fellow CCS alums like Aaron Cockle and Dane Martin as well as notable talents such as Lydia Conklin, Michael DeForge, and (most especially) Warren Craghead, this volume has a striking array of visual styles and approaches to narrative. If I were to choose a single comic to give an interested reader an overview of what minicomics are like at this point in time, I'd give them this anthology.

3. Snake Oil #6, by Chuck Forsman. Here's my original review. This is Forsman's best comic to date, employing a delicate line in its story of a son who cannot please his father, a professional soldier in some unspecified medieval society. While Forsman uses all sorts of formal tricks like chronological fracturing, it's the painful way he explores that key relationship that gives this comic its resonance.

2. Papercutter #17, edited by Greg Means. Here's my original review. Every story was written by Jason Martin and drawn by an impressive array of alt-comics stars like Jesse Reklaw, Vanessa Davis, Sarah Oleksyk, etc. The feeling I got from these quotidian autobio stories was reminiscent of Harvey Pekar at his peak.

1. Thickness #2, edited by Michael DeForge and Ryan Standfest Sands. This is a wonderful, weird project: an alt-comics porn anthology. The artists that DeForge and Sands chose for this issue very much fit into their aesthetic of genre fusion and body transformation. The collection is about the drawings qua drawings, where the reader experiences the narratives specifically as lines on paper in addition to reading them as stories. That thread that connects the opening entry, Angie Wang's untitled story, to the rest of the book. Her story is an otherwise unremarkable set of images about a sexual encounter between two women—it's interesting because of the way Wang uses unusual close-ups and cuts away to just a few lines here and there in depicting desire and awkwardness.

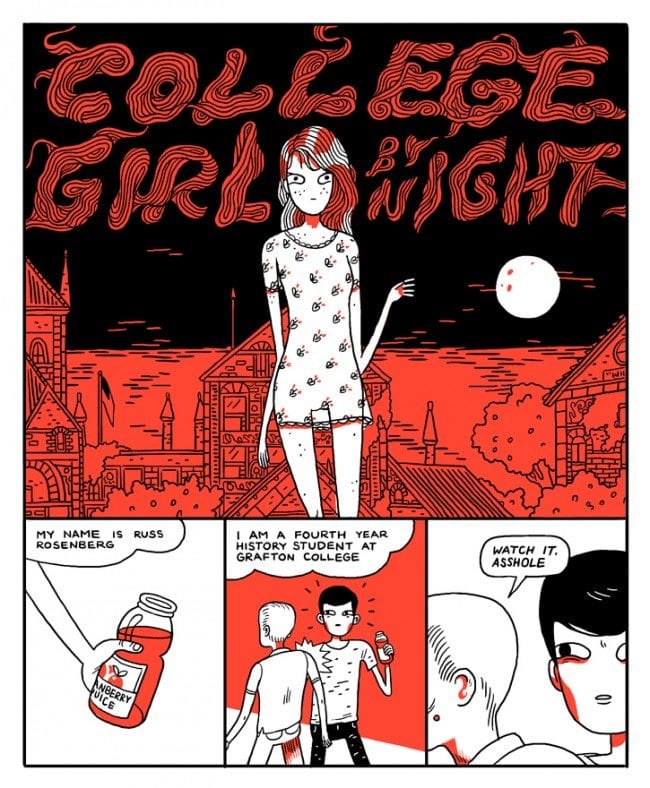

The other four stories are all headliners in their own way. DeForge's "College Girl By Night" is an ingenious mash-up of a '70s Marvel comic (Werewolf By Night), horror, and slice-of-life gender exploration. It's about a young male college student who transforms into a young woman during the full moon. It's both funny and disturbing, as DeForge gives his characters an almost reptilian set of countenances as the nameless protagonist does little else but have sex when he becomes a woman. The way DeForge draws the transformation with flesh melting off is genuinely unsettling, especially during a scene where she changes back to her male form during sex, creating a scene fraught with awkwardness and shame. Even using a highly stylized line, DeForge creates genuine erotic tension in this story, something that's not present in the same manner in the other stories.

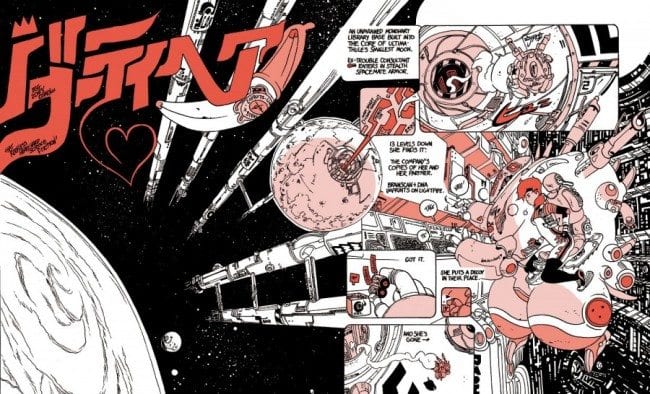

Brandon Graham's "Dirty Deeds" is a throwback to the early part of his career when he did a lot of porn comics, and it's a sci-fi/porn mash-up that uses Will Elder eye-pops for laughs in the middle of graphic, technophilic sex scenes. His clear line and the spot colors make this feel like something that might have appeared in a magazine like Heavy Metal in the 1970s. It's also a gleeful counterbalance to the heaviness of both DeForge's story and Mickey Zacchilli's "Slime Worm". Zacchilli's story is dense, crude and powerful, as a woman goes through physical and metaphysical trials in a swamp. Lisa Hanawalt's exquisitely disgusting comics go to another level with "Early Bird", her take on the student-teacher sex fantasy merged with Crumbian deviant sexual weirdness, all in the service of a groaner of a pun. Seeing the bird-headed teacher's bird-headed penis essentially puking up semen on the ass of a worm-headed Crumb girl is hilarious and revolting at the same time, as Hanawalt goes a step further than in her own solo comic, especially in terms of the explicitness of the images. Throw in the strange and beautiful pin-up by Jillian Tamaki (made all the more exciting given that this isn't an artist who normally "works blue") and a crudely hilarious "True Chubbo" strip, and you have a truly remarkable achievement: an intelligent, unsettling, erotic, and funny work of pornography--and a work of art, to boot.