I had the opportunity to interview not only cartoonist and self-publisher (I Will Destroy You) Tom Neely, but Tom Neely’s parents, on the Seattle leg of his recent tour to promote his self-published graphic novel The Wolf. Bill and Bonnie Neely were RVing up and down the West Coast, visiting their children and travel blogging.

We spoke for a while and I learned 1. They were notably proud of Tom; apparently relations are good between Tom and his parents 2. They had worked hard to expose their children to art and culture despite living in a small town that, in the words of Bill, “was not very accepting of avant-garde art.” They were both very gracious about being interviewed on a side street, in the rain, next to a bar and the Fantagraphics store.

My conversation with Neely was conducted in a vegetarian café (Neely is a vegan) and in the basement library of Fantagraphics; we discussed his body of work to date.

Transcribed by Ben Horak, Janice Lee, Madisen Semet

All images ©Tom Neely unless otherwise noted.

PARIS, TX

KRISTY VALENTI: What was it like growing up in Paris, TX?

TOM NEELY: Sigh. That’s a big question. I have a lot of good memories and bad memories of it. But I think it was good in a lot of ways because, to end up being an artist, it helps if you’re an outsider and pushed aside by a lot of people around you, or if you’re a nerd. You gravitate toward an inner self, and I think being in a place surrounded by farm boys and rednecks — there was some good people too, but I was always different because I was into art and into music. And my parents traveled a lot. We would travel a lot in the summers, and then we would go out, and I was always interested in seeing other parts of the world and interested in doing other things. In a lot of ways growing up in Paris, TX gave me the drive to want to go somewhere else and do something more with my life than what a lot of people around me were doing. I think out of the people I graduated with there were probably only like five or six that even left the city, probably more. I know only two or three of my friends left Paris.

But it was a good place. It was a nice small town, kind of quiet growing up. My dad was a farmer for the first 10 years of my life. And then he put himself through grad school to get his master’s in English literature and became a professor after that at the Paris junior college. So it was fun, I grew up hanging out on the farm all the time with cows and stuff. And then he also had this strong literary influence of tons of books in the house. Dinner conversations were always about existentialism and stuff like that. Which probably I think also helped make me even more of an outsider in school [laughs], being the nerdy, existentialist 12-year-old.

VALENTI: Is there a specific philosophical branch of existentialism that you subscribed to?

NEELY: No, I don’t really subscribe to anything in particular. I think dad got me really interested in philosophy and literature in general. But I’ve always liked a pretty broad range of different ideas: just find parts here that you like, and parts here that you like, and mix it all together to make your own. Looking back, I still really like Albert Camus a lot. His brand of absurdism seemed to fit with my sense of humor. But, I don’t really particularly subscribe to anything.

VALENTI: I had the opportunity to interview your parents. Your dad said he saw elements of Franz Kafka and Joseph Campbell in your work. Would you agree or disagree?

NEELY: Yeah, I’d say that. I was probably 10 when my dad gave me a collection of Kafka short stories to read, 10 or 11. He’s one of my favorite writers. I’ve never really studied that much Joseph Campbell, but my dad was always talking about Joseph Campbell when I was growing up. So I just picked up a lot of it just from listening to him all the time. I could see that.

VALENTI: When your dad said that, it made me think of your ectomorphic bodies and “A Hunger Artist.” So I didn’t know if that might have been a strong influence.

NEELY: Could be, maybe somewhere in the back of my brain. He’s definitely a big influence in there, but not necessarily a conscious one. Kafka’s definitely one of my favorite writers. I’m not very good at talking about writers intellectually, though [laughs]. I just love them and try to absorb their ideas, and then they come out of me in another way.

VALENTI: Let’s talk a little bit about your siblings, because you said you were the youngest. How much younger are you than your brother and your sister?

NEELY: Six years younger than my brother, and my sister is nine years older than me.

VALENTI: So there’s a gap, where they were way ahead of you in school.

NEELY: Yeah.

VALENTI: Do you think that affected you at all?

NEELY: Yeah, in a lot of ways. My sister went to college when I was in second grade, so we were really close when I was really young, but I think, until the last couple of years, once I got married, I think she still thought of me as that 8-year-old she left behind. So we’re not as close. But my brother and I were always really close. I wanted to be him when I was really young, but then he went to college when I was in sixth grade. So I had the benefit of having siblings, but then I also got the benefit of being an only kid and figuring stuff out for myself. Because early on I just wanted to be him, so I dressed like him, listened to the same music as him, and all that stuff. But then he went away, and I had to find my own thing, and that’s when I really started to get more interested in art and getting more focused on that. I remember very distinctly around sixth grade starting to discover bands for myself, and then I’d call my brother and be like, “Oh, have you heard of this?!” and he’d be like, “Oh no, I don’t like that stuff.” And I was like, “What? Really?!” So then the concept of having your own thing became really important to me, so I think it was good to have siblings, but also have time when I was on my own a lot.

VALENTI: According to your mom, you’re all in the arts in some fashion.

NEELY: Well, not all. My brother is a musician, and he does a lot of music for TV and movies. I just found out yesterday, because it was on TV, I guess he’s doing the score for that show Pan Am, and The Mentalist, and a few other things, and he works on a lot of movies and stuff. He’s definitely a really incredibly talented music person. My sister used to be into writing and stuff in college, but she didn’t keep up with anything, and she never really pursued art or writing as much. She seemed to always be interested in writing poetry and such when she was younger, but I’m not sure what she does any more, as far as that goes.

But my mom just thinks everybody is … if you do anything, she’s like, “Oh you’re wonderful; you’re an artist!” [Laughs.] It was good, my brother and I were both definitely very creative, and we’ve always egged each other on and encouraged at the same time. I was always interested in music as well, and he was always interested in art, so it was good. He was always a good influence to have around.

VALENTI: Does he do personal music?

NEELY: Not as much anymore, but he does some. He has two kids and an expensive house; so I think a lot of his time gets taken up by music for pay. But when I was younger, he lived in L.A. when I was still in high school, and I would come out to visit him sometimes. I can remember a few times where he had composed a string quartet and put together a concert in a music hall somewhere and conducted a string quartet or something with his original music, so that was always really cool to see him.

He’s not as much of a DIY-er, but with some of those things he was doing that, and I think that always impressed me, [the idea that] you can just make it happen yourself, so that was good to see that when I was in high school, to see him doing stuff like that. But over the years it’s gradually become more and more just work focus, but we talked recently about doing some collaborative thing, like an art show with his music, and combine it somehow, I don’t know. We talked about that a lot but we’re both so busy; it’s hard to find time to figure out when we’re going to do it, but I think eventually we will.

VALENTI: Are you familiar with the Texas underground movement, like Gilbert Shelton and Frank Stack?

NEELY: I wasn’t until later. I’m still not that familiar with all that. But I didn’t know any of that stuff growing up. Never been a huge Gilbert Shelton fan, but I’ve read a lot of that stuff. But that’s about it. Until after art school, I was really oblivious that there was even underground comics around. First time I heard of [Robert] Crumb was when I saw the movie in college.

VALENTI: The reason why I bring it up is, I was talking to Frank Stack about this — I interviewed him this summer at the convention. The thing that I think really characterizes the Texas branch of the underground movement is a strong DIY attitude and aesthetic. And you’re obviously committed to a DIY aesthetic. So I was wondering if there’s something specifically about Texas that brings that out?

NEELY: I think for me, it was just like I said about growing up in Paris — I never felt like anybody else was gonna help me do what I wanted to do. So I just had to do it myself, and I was determined to do it. I wasn’t going to let anybody tell me, any gallery or any publisher or whatever or art teacher, “No you can’t do it that way.”

I’d be like, “No, I’m gonna do it. And if you’re not gonna help me do it then I’ll do it myself.” It’s how I always thought of things. And over the years, it’s just become more important to me as I think the whole DIY thing has become a part of my process and a part of my art in general. But originally: “Well, fuck you. If you’re not gonna help me I’ll do it myself.” [Chuckles.]

But I wasn’t really even aware of a DIY culture especially in comics until after college, when I went to A.P.E. Well, I went to Comic-Con, I started going to Comic-Con in ’98. And then in 2000 I met Jesse Reklaw and Martin Cendreda and a few other people at Comic-Con. And they showed me: “Hey, there’s this small press area of people making their own comics.” And I had had my own Xeroxed comic that I didn’t know anybody else who’d done that. I had submitted it to publishers, got rejected by every one, so I might as well just make it myself and see what happens. So then I discovered there was a whole DIY culture to comics and got really involved into that. But I had no mentors in that realm until I was 25 [chuckles].

TEACHING

VALENTI: So tell me a little about leaving Texas to go to art school, your decisions … you have those two degrees, right?

NEELY: When I was getting out of high school, my parents were supportive of me going into art school or whatever I wanted to pursue, which was great, and they took me around to see a bunch of schools, and at first I was looking at art schools like Chicago Art Institute and Maryland Institute College of Art in Baltimore. But my parents were also like, well, you should get a more well-rounded education, because you’re going to need to get a job. So I eventually decided from that influence that I shouldn’t just go straight to art school. Everybody else at my school was going to either University of Texas or Texas A&M, and I just wanted to get away from them, so I went the other direction, but not that far, because I had a girlfriend in high school, so I went to the University of Tulsa.

But that was great. It was the first time I was totally on my own, arriving somewhere where nobody from my high school was there and my parents weren’t there or anything. Some of my best friends in the world are from Tulsa, like the guy I was staying with this weekend — Matt, he was my roommate for a while. Several of my friends from Tulsa ended up moving to L.A. around the time I went to grad school, and then we all ended up back in L.A. together. So Tulsa ended up being a really good place to be. And I think it was also a good transition, because if I went from a tiny farm town to…because I almost went to Maryland Institute, that was my first choice before I chose Tulsa. But I think that would have just destroyed my small-town brain if I had gone to that urban environment immediately, so Tulsa was a good transition to a small city, and then off to San Francisco after that.

VALENTI: Is that where you got your teaching…

NEELY: Yeah, at Tulsa I had a double major with a B.F.A. in painting and printmaking and then a B.A. in Art Education. And then I spent a year teaching junior college there while I was working on my grad school applications and portfolio, and then I went to San Francisco Art Institute for my M.F.A. in painting.

VALENTI: When was that? What years?

NEELY: I was in San Francisco at the art institute in ’98, graduated in 2000.

VALENTI: So do you like teaching? You said you might want to do more.

NEELY: I’ve been really wanting to get back into it. [San Francisco] Art Institute was such a weird situation for me that it really burned me out on school and the fine arts world. And so I just found myself wanting to run away from that and get a commercial art job and make comics instead of working in an art supply store and pursuing galleries and teaching jobs. But now, after 11 years of doing freelance animation, I’ve been feeling rather unfulfilled in that aspect of my life, because it’s just the same videogame, different characters for these anonymous Flash Disney websites, and I get burnt out on that. I mean it’s a good job, I can’t complain. It pays wells and keeps me afloat and gives me the free time to do my comics, but now, 10 years later, I feel like I maybe have something to offer as a teacher that I didn’t when I was right out of school.

And I like the idea of trying to encourage other kids to do that, to make art and comics or whatever. So I’ve been trying to find a teaching job lately, but L.A. is difficult for that. I think I’d prefer teaching college level, but in L.A. you’re competing with people like John Baldessari and Mike Kelley for teaching jobs. Or the Clayton Brothers or all the other famous artists that are in that city. So that’s hard to do, but now I’m starting to look at some after-school programs at little art centers around town to maybe start doing some teaching part time. Maybe I can build up my résumé again, and eventually get to teaching at college.

VALENTI: You expressed some skepticism about comics colleges. What would be the difference there?

NEELY: My friend Matt was asking me this this morning, about teaching, and I think I’d rather be teaching more art in a general sense. I think it’d be really fun to just teach Drawing 101 and Painting 101. Just the basic beginning stuff, where the kids are new to it, they’re open, and they haven’t had their spirits squashed by too many teachers yet. So I think that would be more fun than … I have friends who teach illustration for comics or how to do comic strips: these more specific, rigid ideas of teaching that I don’t really like. I think I’d rather teach more in a general sense, like learn how to draw and then you can do anything, you can paint, you can do comics; you can do illustration, whatever.

The whole teaching comics in school is … well, if someone offered me a job doing that I would do it, but there’s something really weird to me about that. Because as I said earlier, it feels like I’m part of maybe the last generation of independent cartoonists who had to figure it out on their own, because we were all shunned by art schools. I even had that in my art school. I somehow managed to convince them, and I did graduate basically doing comics, but I did comic oil paintings instead, so it worked out somehow. But I was in a school that was mainly focused on installation and new genre art and performance art. So me just doing little … well, A) they were against painting, and B) they were against comics, so I was making basically one-panel comic strips as oil paintings, but I somehow convinced them to give me a degree for that.

THE WOLF

VALENTI: Does that have anything to do with The Wolf at all? Did you get back around to that?

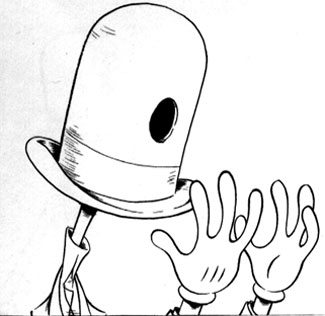

NEELY: I think more like a painter in a way, but I love telling stories that are bigger than you can do in a painting. So I think I’ve always been trying to merge the two, and The Blot was more specifically making a comic/graphic novel, but with a weirder, arty idea behind it. But then, with my comic strip poems, it’s my first attempt at really trying to do something that was more art-minded, but in a comic form. And the originals of that are 30 inches by 15 inches. They’re pretty big; they work like paintings.

And then The Wolf started out as a series of paintings. I had a solo art show about three months after The Blot came out at a gallery in L.A. of all these pornographic werewolf paintings, and also the paintings from the guy eating himself — “Self-Indulgence.” The spark of the idea was in those paintings, and then it grew from there. It just felt like there was a much bigger story to it that was bigger than you could really do in an art show or in a painting, so it just became this really long series of paintings that told a story.

And that was also influenced by having the art show and The Blot happen at the same time was really interesting to me, because I had a really good comparison of the two worlds and how they affected me. Whereas the Self-Indulgent Werewolf art show was up for a month, got a couple of write-ups, but a couple of months later it’s all forgotten, and all those paintings are in my closet. But I’ve been on the road at shows for the last four years with The Blot and at SPX last week I sold a dozen copies, so it’s still getting that art out there, whereas that art show is in the past.

I approached The Wolf almost like another solo show, but in book form. It’s just a big narrative series of paintings in which the end result, instead of being in a gallery, is in a book, so I think of it that way. I feel like comics is a much more rewarding experience than the gallery system has been for me. I think the Bound & Gagged book was an attempt at doing that too, but like doing a group art show as a book as opposed to just a gallery show.

VALENTI: Let’s talk about horror movie imagery in The Wolf. You go through some of those tropes, like the wolf representing the primal, and rehabilitating him into a romantic hero. Were you consciously playing with that?

NEELY: Definitely playing with that a lot. I’m not exactly sure where The Wolf came from, but it just started happening in my sketchbooks and I just let it go. With the original set of paintings, it was definitely about a primal thing, sexual, getting in touch with what we are as animals and those ideas. I’m also a nerd too, so as soon as I get this idea of working with a werewolf, I want to read everything I can and make sure that I’m not copying anybody. The more research I did on werewolf lore and books and movies, most of which are not that good, I wanted to subvert or invert the ideas of the traditional werewolf story, and it was definitely at that point already evolving into a love story to my wife. But the traditional werewolf story is more a story of rape, and I wanted to specifically invert that idea. It wasn’t like, here’s my agenda: I want to subvert werewolf stories. That just happened organically as I was studying it. I already knew the story was about me and my wife, but all this other stuff was tied into it. There’s a lot of symbolism in the backgrounds, and other aspects of the story that are often inverses of their traditional symbolic value. I read a lot of books on traditional symbolism in classical painting and stuff like that, often taking a specific symbol and inverting it, even the cover, which is a traditional vanitas painting, it’s trying to speak to that tradition, but vanitas is all about death and the acceptance of death and usually the fruit would be rotting. I wanted it to be the opposite, so I wanted it to be representing life, but with an acknowledgement of death. So it’s a slight inversion of the original idea of a vanitas, and that’s how it relates to the overall story of the book, inverting the traditional werewolf story into a love story instead of rape.

VALENTI: It’s the most natural of your books; it’s the one that’s the most set in nature. It’s moving out of an urban interior. I’ve don’t think I’ve seen that yet in your comics.

NEELY: Yeah, it’s something I’ve been thinking a lot about too. Ironically I’ve started to — after 10 years of a love-hate relationship with L.A., I’ve finally started to really love living there, and it feels like home. But it was always a love-hate of the urban environment and wanting to get — just desperate for years to move somewhere with more space and more nature. So there’s that aspect, too, of that desire. But that becomes more metaphorical, about just trying to find yourself and where you’re at peace and you can find it anywhere if you look for it. So I think that’s maybe where I’m at now. I’m at peace with L.A. even though I hate lots of aspects of it.

Nature’s become a lot more important to me over the years, especially since I moved into living in cities. When I was a kid, all I ever wanted to do was to travel to big cities and go to museums and see all the interesting things, because there was none of that at home. But now that I’ve been living in cities for 15 years, whenever I go on vacation, I want to go to Hawaii or go to Big Sur or go to somewhere where there’s lots of hiking and nature, and get away from the city. Especially with comics, ’cause I’ve spent so much time travelling to big cities, which I love too. But I want to have down time. I just want to go retreat and get away from it all and just get away from technology and everything. So I think there’s a lot of that in there.

VALENTI: I want to talk about the color in the sex scene. Was this the first time you used color in a comic? I guess you did use some in the —

NEELY: There’s some color in The Blot.

VALENTI: That’s a very significant linking.

NEELY: I’ve always been interested in what can you do with an aspect of art. I mean for comics or drawing or painting, any art, any two-dimensional drawing-based art, the basics are black and white. But rather than just like arbitrarily coloring everything just to have a full color comic, I’m more interested in the idea of, “Well, what does color add to this story?” And I flirted with that with The Blot by introducing color at the end, and I really liked the way that that worked and how it changes the story. I wanted to explore that more fully in The Wolf at the point where I was trying to start to off as a black-and-white story, and I always knew that color would be introduced into it. But I didn’t know when or where. And originally it was just gonna be the red skeletons. But then when it got to the point of wanting to represent the connection between the two characters, it seemed like color was the best way to represent that.

When they first meet, I spent a lot of time with my dog [chuckles], and I study dog behavior all the time, just thinking of how can you represent when a dog meets someone, they smell you. So color, when you first get that in that scene, it’s representing how they can connect. And then as that scene progresses he attains color from her and to represent them connecting and fulfilling something that they didn’t have individually. So then you’re just carrying on that idea through the book until you get to the end where it’s all full-color vibrant world that didn’t exist when they were separate. I like the idea of color, lines, any element in art should not be arbitrarily decided upon.

One of the reasons I self-published The Blot was because I definitely wanted color, in the last part of it, and Top Shelf would not do that. They didn’t see the point of it, they didn’t agree with me. And I agree from a business standpoint, publishing-wise it adds a lot of expense. But if you, traditionally, you know indy comics are more often black and white for budgetary reasons, and mainstream comics are full color for completely arbitrary reasons. And I don’t think those decisions should be made based on budgets or marketing solutions. It should have a meaning and it should have a reason for being there. And I think that comes more from my painting background.

And my interest in film too, ’cause especially in the modern day, when some directors choose to do black and white, that’s a really impacting idea. I remember a few years ago that movie The Mist came out, and Frank Darabont originally wanted it to be a black-and-white movie, but the studio forced him to do it in color. And then when they released it on DVD they released both versions, and the black-and-white version is much better; it makes more sense. And it’s just one of those things, like dealing with Top Shelf, it’s like that’s an arbitrary decision. That movie company wanted to do it because they can’t market a black-and-white movie as well.

VALENTI: I think there is a wolf cycle going on right now in indy comics; there was that werewolf anthology they put out at CCS.

NEELY: I haven’t seen it.

VALENTI: I don’t know if it was the whole vampire-werewolf-zombie cycle or —

NEELY: I have no idea. I have specifically avoided reading most comics while working on The Wolf. Except for a few exceptions from friends, but I didn’t want to be influenced by anything contemporary or any external ideas. But I was very conscious of Twilight and all that stuff happening around me. And my mom was always like, “Oh, I think your book is gonna do really well, because everybody’s into werewolves and scary stuff.” And I’m like, “Mom …” And she’s like, “You should market this to the Twilight…” And I was like, “I’m not marketing my semi-pornographic book to teenage girls.”

[Valenti laughs.] That will get me arrested [chuckles].

It’s just a coincidence. It wasn’t any specific attempt to tap into that market, I was just off doing my own werewolf thing in my cave. And apparently there’s other stuff going on too — I didn’t even realize Jason did a werewolf story until somebody told me that the other day. So I haven’t really kept up with anybody [chuckles]. That’s what’s nice about finishing it, is now I’m getting to read all these books that I’ve avoided for the last five years. And someone else brought up that there’s a lot more sex in indy comics right now too. And I was unaware of that as well. Maybe there’s just something in the collective unconscious that’s leading us down that path. But it wasn’t any conscious attempt at being a part of that. I’m largely unaware; I guess there is a lot of it.

VALENTI: The Wolf was in the The Blot too — not the same wolf, maybe. Does that have some kind of personal significance for you?

NEELY: There’s not really a specific thing, I think everything starts as imagery. My process always starts with paintings and single images. The Blot started off as just 20 paintings of the character and then just dropping ink on them, and they were supposed to be these weird, abstract one-panel comic paintings, but then the story grew from there. So everything starts as single-image paintings, and then once it’s done, I sit and think about what it’s about, and sometimes it grows into more work, and sometimes it stays as a single image. I definitely approach each page like a painting, especially The Wolf, thinking of them all as individual pieces, but they all have to rely on each other too.

MUSIC

VALENTI: Your video presentation for The Wolf had music you did: heavy metal and banjo. Why is that such a big element for you?

NEELY: I think it’s just fun. I’ve always really liked making music and I’m not really a great musician, but I like making noise and experimenting with sound. I play the banjo around the house when I’m taking a break from drawing or freelancing, and I just want to chill out and think, and I will bang around on my banjo and play with my dog in the yard.

I was talking to my friend Skinner, who is an artist from Sacramento, because he’s in a band, and they just recorded their first album, and we were talking about, once your art starts to get some exposure, and you start getting known for doing one thing, there’s a part of me that wants to go and do something that’s more hidden. That’s what compelled me to go make an album, because nobody has any expectations for me making an album, so I can do whatever the hell I want. That’s how I try to approach my art and my comics, but it becomes more complicated the more you get interviewed … the more eyes that are on you. I remember reading a Basquiat biography once, and he talked about him doing music too as a secret outlet for creativity, where people don’t have expectations, that I think can be important to some artists. I think that’s what compels me to do it.

But as far as how music applies to The Wolf, originally it was going to be a book with a soundtrack composed by my friend Aaron Turner and the original idea was that I love his music and I like music in general, so I thought it would be interesting to combine the two and collaborate. But also, one of the frustrating things about doing largely wordless comics is that I spent four years working on The Wolf and someone can read it in 10 minutes and be done. I was thinking, how can I make people slow down and spend more time with each page and think about it? Because I put a lot of stuff in there that I think isn’t always that obvious in a quick read, and you can read it quickly and it works, but I think there’s a lot more to it if you can spend more time with it. So, I thought if I added a time component, which would be music, and it was originally divided into four chapters and it would have four songs, and each was around 10 or 12 minutes, it would force you to spend at least 15 minutes with each chapter. But, then that fell through; we weren’t going to do it together anymore.

But I think it actually worked out better because, I think a lot of people wouldn’t necessarily connect to that music, and that can create a weird thing for people that aren’t attached to the music, they might feel like they’re not getting a part of the book that they should, where really, they weren’t specifically married in my brain, but then I started thinking about how that could effect it. So I’m actually happy that it’s a separate entity, and it turned out that I wanted to make a preview movie, a trailer, for the book. I’ve seen a lot of other trailers for books and I thought, let’s try another publicity angle, and it seemed to work really well with the album. The music I originally recorded for my art show in 2007, and it was my soundtrack for the art show, but I think it worked really well when I started playing around with the video editing. I figured it was a fun way to put it together.

VALENTI: Metal is a visual genre of music; it’s very theatrical. Do you think that’s one of the things you responded to?

NEELY: As a kid I was always drawn to bands that had a strong visual presence, whether it was Iron Maiden with their Eddie character or Pink Floyd with all the Storm Thorgerson surrealist album covers. Growing up in a small town where nobody was listening to anything I listened to, often my only way of finding new was, I’d go and look for something with an interesting cover, and if it was a cover I liked, I thought, “Wow, that’s really cool, it must be a good album or it must be an interesting album,” so I’d give it a shot.

Art and music always went together in my brain, and I’ve always wanted to be a musician rather an artist, so I’ve always been compelled to find ways of merging the two or working with musicians, doing album covers or posters. When Aaron asked me to do The Melvins comic for his record label putting out a box set for their album, that was the perfect idea for me. That led me to the idea of doing the opposite: whereas I wrote a comic to their album, I thought it would be cool to have somebody write music to my comics, so that’s how the idea of having me and Aaron working together came together. Also, growing up with my brother, he was always doing music and in bands. They are all tied up together for me.

(Continued)