From The Comics Journal #291 (July 2008)

Today’s mainstream superhero comics aren’t exactly known for nourishing the careers of artists who are quick to ignore the latest fashion. That’s one of the unique things about comic-book artist Tim Sale. Be it through luck, fate, elbow grease or sly calculation, Sale’s managed to create a successful career out of illustrating the cape-and-cowl crowd exactly the way he wants to, in a style distilling a century’s worth of influences, in all manner of popular media.

Born in Ithaca, New York, Sale grew up in Seattle (evident, to the ears of this East Coast city dweller, in his calm, thoughtful speech patterns), and on a steady diet of comics and pop culture. The passions he’s accumulated inform his conversation — littered with references to the Beatles and vintage film noir — as well as his work. His only formal education was a two-year stint at the University of Washington. And a brief turn at New York City’s School of Visual Arts and a Manhattan workshop, staffed by the Marvel artists he adored as a child, only confirmed for Sale his love of the West Coast. He now resides in sunny California.

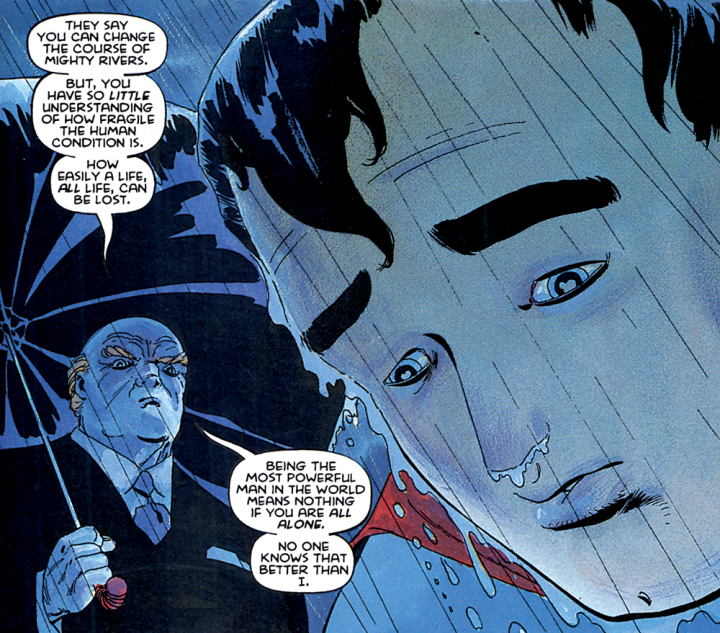

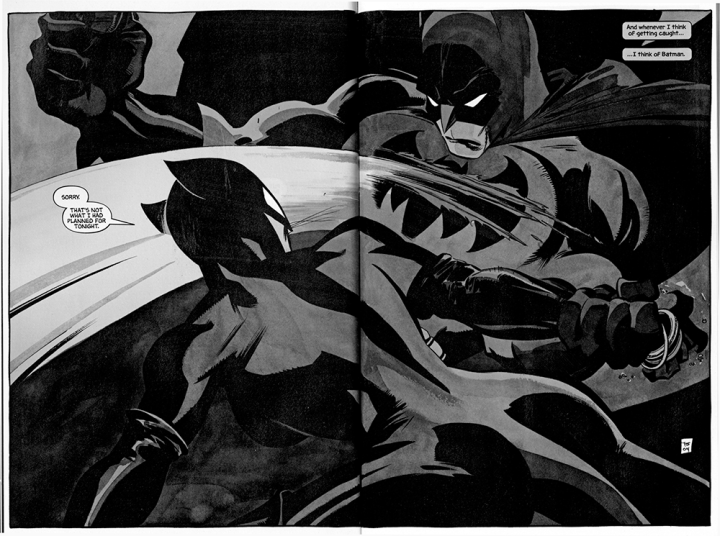

Sale claims he pays no mind to those who deem his subjects insubstantial, and his focused approach has led to hit titles like Batman: The Long Halloween and Superman for All Seasons — titles that have influenced the ongoing series of Christopher Nolan-Christian Bale Batman films and the CW’s popular TV drama Smallville. Sale’s media connection increasingly broadened when he was recruited by NBC-Universal’s hit Heroes to provide the comic artwork featured in many of its episodes.

But as much as he loves superheroes, and as well as he’s done illustrating their adventures for other creators, Sale reveals in the following interview that he’s finally ready to try his hand at creating his own property, and, in so doing, exploring new forms of freedom and escapism.

— Joe McCabe

* * *

Joe McCabe: It seems that there are a lot of ironies to your career—one of which is the fact that you’re colorblind, yet you’ve worked primarily in mainstream comics—a medium that, to many people, is synonymous, if not defined by, color. The term “four-color,” for example, is often used as a substitute for the word “comics.” As a young fan of comics, did you notice differences in the ways you perceived them compared to your peers?

Tim Sale: No, I didn’t. I’m not a social misfit. But I’ve never been somebody who had a very wide circle of friends. But I had a couple of guys on my block who … at least for a very short period of time, we were all into comics. But color was never a part of that. What was cool about comics was not the color. At least we never talked about it. And I know that for me it was never an issue. It’s funny — I’ve recently been, because of my website, sharing some of the artists that were an influence on me as I was growing up. And so I was scanning artwork and showing them and talking about them and asking for other people’s opinions, and often color comes up, and the silliness, for instance, of how many of the Marvel comics of the ’60s were colored; and that was my primary and initial introduction to comics and comics influence. And it never occurred to me. It wasn’t until someone else said, “Well, I don’t like it, because of the color,” that I even considered it. And even to this day … For instance, just last week, I’d been sharing some magnificent Jack Kirby artwork. For somebody to look at that stuff and say, “I just can’t get past the color,” is missing the point entirely, it seems to me. And that’s not to defend the color. It just seems irrelevant. Maybe it was easier to seem irrelevant to me because of my color blindness. I don’t know. That may be just too hard for me to say objectively. I know that I feel it strongly that the point of comics is not the color. And when I call the coloring of Marvel comics and the Kirby comics in the ’60s “silly,” I do think it’s silly, but it’s wildly colorful maybe just to grab attention, I guess. And to make it sort of coloring-book-like. But it never really seemed the point to me. I do know what you mean when they talk about “four colors for a dime” and that sort of thing. It was not a concern of my friends either, my friends who were not colorblind. But I do know that as I got more into comics, I discovered at some point the Warren black-and-white comics. I was immediately attracted to them. And I was aware of them partly because of the black and white. But that seemed to me to be more about the contrast and the drama inherent in black and white, not because it wasn’t in color.

I did learn after the fact that many successful comic-book artists, from John Byrne to Alex Toth, are colorblind. It’s an interesting little side note — I always think of it as a side note — that comics is one of the ways you can be a successful professional artist and be colorblind, because you’re working primarily in black and white, if you’re a penciler or an inker.

I once heard Will Eisner remark that, to a comic-book artist, the presence of color was like that of a full symphony orchestra playing behind a musician who’s trying to do a solo. He seemed to regard it as an obstruction.

Well it’s not an obstruction for me. People like Darwyn Cooke, I have a huge admiration for them. But it’s more than just the way that he can color, although he works with Dave Stewart, as do I primarily. But he can do everything. It’s not just color — he knows production inside out: writing, penciling and inking, the computer. I will say that I enjoy working with Dave Stewart inordinately, both because he’s a great guy, but also because he’s hugely talented, and enjoys working back and forth with pencilers and inkers. And he’s very accommodating and very imaginative in how that collaboration can be. He can take the barest notes and turn it into something pretty spectacular. And my relationship with any colorist has been helped hugely by computers, because you’re not dealing with a separate separator; the production line is much more streamlined than it once was, even just a few years ago. Things like color holds or different effects, textures, can be much more easily imagined and described by me and then executed by Dave or another colorist. That whole process is so much easier and allows so much more freedom than coloring in comics once did.

You began by talking about irony. I don’t how ironic it is, but it is certainly true that I can’t color, and yet I have opinions about it. But it’s rarely shaped how I appreciate comics.

Bi-Coastal Education

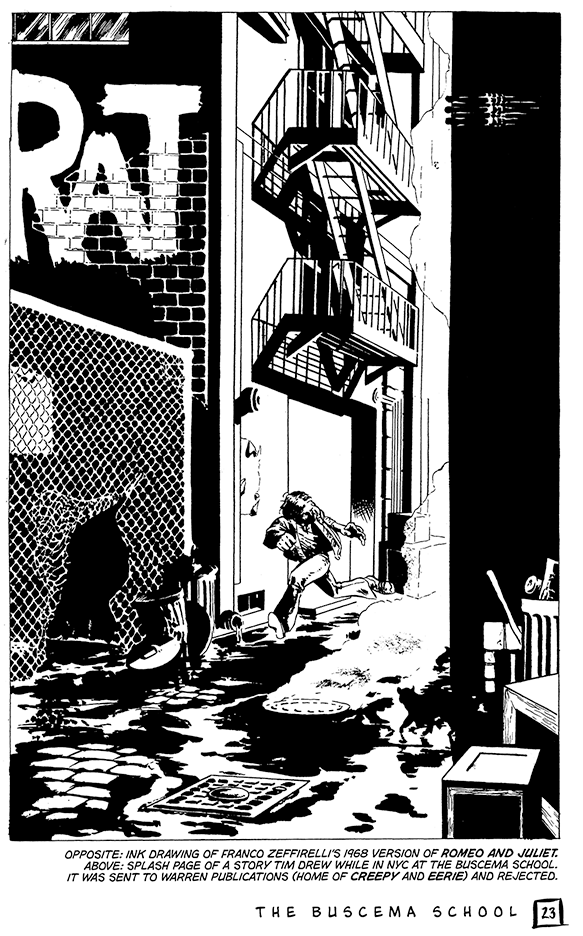

Your career in comics has taken an interesting circuitous route, because you attended the John Buscema School in New York, and learned more about the kind of comics you grew up on, but then you kind of took a step back for a while, and returned to the West Coast.

Right, I did. Yeah, I was pretty burned out by the time I finished my 20th year in New York, in the Buscema School of Art. What is ironic to me is the primary thing I thought I might never get was storytelling. I knew that I could draw. I had affirmation of that both in the Buscema workshop and the School of Visual Arts. But drawing comics was an entirely different animal, it seemed. I was constantly being told it was an entirely different animal, and the main thing that I couldn’t get was putting together what seemed to be a whole bunch of rules that you had to follow that ended up being storytelling. And it’s ironic now, because if I end up being thought of in any way well now, usually one of the things that comes up is my storytelling.

I had 10 years between my experience in New York and actually working professionally in comics. Something just seemed to gel during that time. I’ve never really sat down and looked hard chronologically at it. My first work ever in comics was as an inker, and I know that I wanted to do that because I thought that I couldn’t tell a story. It was a way of working in comics, drawing — having fun that way, not having to worry about telling a story. That job was inking Phil Foglio on a WaRP Graphics comic called Myth Adventures. I did about a dozen issues of that. It became more boring as it went on. It was actually pretty exciting at first, and my relationship with Phil was never close. But he had worked a little bit more than I had, and so he was an experienced voice that helped me in certain ways or asked me to do certain things. But as it went on, it became clear that we were both pretty limited in the book.

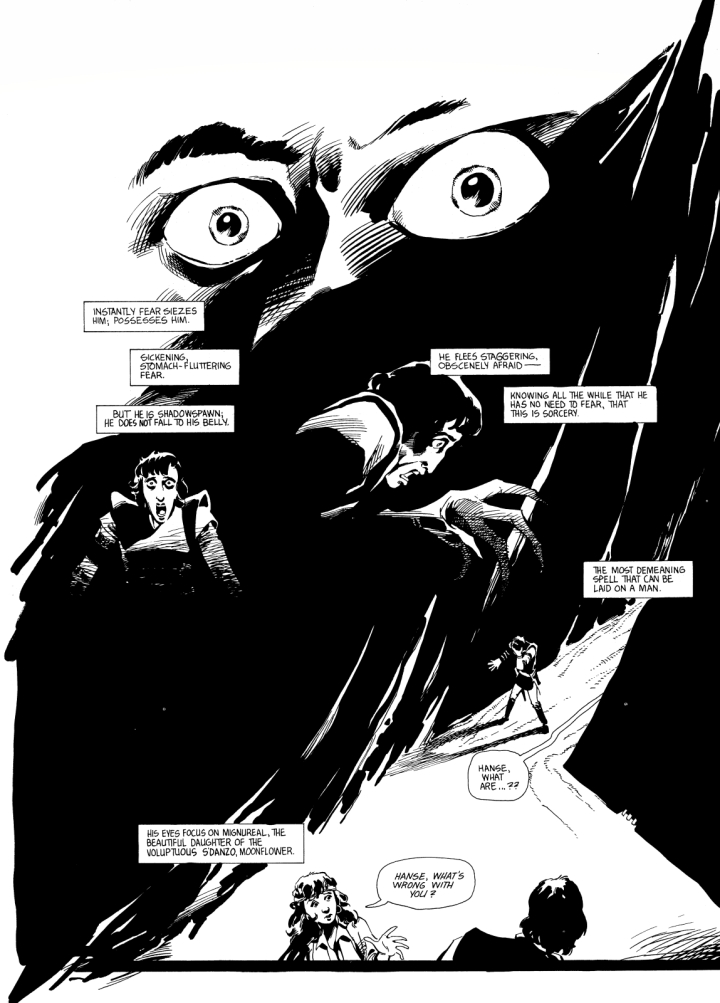

The next thing I did though was to pencil, ink and letter a book called Thieves' World. And I learned a lot in doing that, because I was working with two writers who had never done comics before, although they were professional writers. Thieves' World was a successful series of paperback anthology short stories — Ace or Dell published it, one of those fantasy publishers that thrived, in the early ’80s in particular. There were maybe half a dozen books out by the time they decided they wanted to try to adapt them into comics form. But there was an established publisher who had never published comics before, called Donning/Starblaze Graphics. And they had discovered a small goldmine in reprinting Richard and Wendy Pini’s Elfquest, in anthology form. They wanted to branch out a little bit and see what they could do, so Robert Asprin and Lynn Abbey were the editors and writers, sort of the founders, of the Thieves' World shared universe. Because Robert Asprin was the one who wrote the Myth Adventures stories, that’s how I knew them. They came to me. I was cheap, I was young, I was hungry — well, I was 30, but relatively young and hungry. That’s how that started. They saw some work of mine that I had put up in an art show at a fantasy convention. And it was kind of fantasy work, so they said, “Well, let’s ask Tim.” So I did that for a couple of years, and because they had never done comics before, I was really sort of the voice of comics on the team. To be fair, there was also a woman who had been an assistant to Archie Goodwin at Epic Comics, by the name of Laurie Sutton, who was our editor. She was helpful and welcoming to me, but there really wasn’t much back and forth between us. And it fell to me to do the storytelling as it were. And I learned an awful lot at that time. I know that I was looking a great deal at Dave Sim’s early Cerebus work, influenced both by the black and white of it, and by its storytelling, how playful or how straightforward he could be. No matter what the story or subject matter was. What to pay attention to and what to move quickly through, primarily. That was influential and helpful to me, but I was largely self-taught. In the intervening 10 years, something just seemed to click somehow. And then being thrown into the deep end of the pool with Thieves' World was also helpful. A lot of that changed or modified when I started [in 1991] with Jeph [Loeb], also, on Challengers of the Unknown, which was my first mainstream work.

I’d done a lot of drawing in the intervening 10 years. My sister and I had a company called Gray Archer Press that was largely fantasy stuff. It was all black and white, it was notecards and prints, portfolios, which, again, were popular in the ’70s and early ’80s. We never really made much money, but I did a lot of drawing during that time, and I kept my hand in. But that wasn’t storytelling. There really did seem to be something subconscious that happened by the time I came back to comics. Storytelling suddenly made sense in a way that it hadn’t.

Was it sparked in part by the mid-’80s renaissance in comics?

Well, the black-and-white boom, of which Cerebus was a big part. But then when Thieves' World ended, which was late ’80s, Dark Knight Returns and Watchmen and The Killing Joke, Daredevil: Born Again, all that stuff was setting the world on fire. And that hugely influenced the work that Jeph and I first did and the approach that we took to Challengers, when we started on it. That’s why it was kind of as crazy as it was and as conceptual as it was, which is not the way that Jeph and I work at all any more.

When you went to New York, having grown up on the West Coast, did you find it incredibly romantic to be studying comics in the city in which they were more or less created, and where the Marvel comics that you loved as a kid were born?

Sure, I don’t know how much of that was [growing up on the] West Coast. I mean I could have lived down the street and I still wouldn’t have known them personally. But absolutely, I worshipped Buscema’s work. He was pretty deep into Conan by the time I was there.

He supposedly never cared much for superheroes.

No, he didn’t. And — if you want to talk about irony — I never liked any of his work except the superhero stuff. I never liked his Conan work for instance. But as an artist, one of the things I talk about with my friends is how poor a judge of their own work an artist is, in any field. Now, that’s a very judgmental thing to say. But if what an artist, and rightly so, is going by is how much fun they’re having, that isn’t necessarily reflected in the quality of the work. One of the easier ways to describe it, perhaps, is when you’re younger and struggling, you’re not having a whole lot of fun, but you’re just grinding so much more into the page, the work, that it has an energy to it that it doesn’t have even when it’s more fun. But regardless, there was a huge amount of romance involved with the idea that I was in New York, and learning from three people that I had really admired to various degrees — and that would be [John] Romita [Sr.], John Buscema, and Marie Severin, who were teaching at the Buscema workshop. I didn’t like New York, and that was part of my problem. It was a whole other experience — that is the 3,000-miles-from-the-West-Coast aspect of it. But I had grown up reading these guys. I was currently reading these guys. It was a huge thing, absolutely. I turned 21 when I was in New York at school. We shouldn’t really hit too hard at my experience at the School of Visual Arts [laughs], because I didn’t really go all that much. I was accepted and I did attend classes, but I remember very little of it, and I know I didn’t get all that much out of it.

So your formal art education is pretty much the two years you spent at the University of Washington?

Right, and self-taught. It was primarily life drawing that I got something out of. And I enjoyed that a great deal, working with charcoal, live models; both 30-second gesture drawings and hour, hour-and-a-half-long-or-more finished charcoal drawings. I like that a lot, but that was about all that I liked. I took some painting classes, and you might imagine how that went, being colorblind.

For the record, could you define the type of colorblindness you have?

I can try. It was once defined for me, and of course I forgot it. But it is not red-green, I can start that way. I was told by somebody who knows such things that there may be 20 different variations, if not more, of being colorblind. The easiest way for me to describe it is that I can see color but I can’t create color. It’s more complicated than that, because I can look at something and see something and other people say, “No, it’s not that.” And it’s true. But most of the time that isn’t what happens. I mean certainly I can do primary colors and I can see earth tones, I can see warm and cool colors. That sort of thing. If somebody says, “No, that’s hazel — it’s not brown. That’s violet — it’s not purple,” well, I happen to know people who are not colorblind who have that argument as well. Jeph would argue for hours with a professional colorist about a certain color and insist that he was right, and yet make fun of me. That’s what used to happen a lot before I got tired of listening to that sort of thing. So I’m aware that that happens, as well, but the easiest way to say it is that I can’t go, “You know what would look good next to this color? It’s this color,” and “It would look even better if there was a little bit more magenta in it.” But it’s either value or hue, and I never remember which one is which. That’s another way of describing it, but it does have to do with intensity also. The misperception is that somebody’s walking around seeing black and white. And it’s certainly not that. But most of the time when I have conversations with colorists, I talk warm and cold, and mood, and then decide what colors best represent those things.

Meeting Matt Wagner and Jeph Loeb

Getting back to where you left off, in the late ’80s, is that when you met Matt Wagner?

Well, I mentioned Laurie Sutton earlier, and when Thieves' World was winding down, I realized that I’d done a fair amount of work in comics, but I didn’t know anybody who could further my career, and she suggested somebody that ended up being very, very helpful to me. That person was Mike Friedrich. Now Friedrich had been a writer in the ’70s, primarily DC , but he’d worked with artists like Neal Adams. He went on to self-publish something called Star*Reach, which was an early attempt at having people own their own artwork, create their own characters, and make some money with it. That didn’t continue, but he then branched off into being an agent, and Laurie Sutton went, “There’s this guy. Why don’t you contact him. I know him. I’ll put in a good word for you.” So I put together a portfolio, sent it Mike, and Mike said, “Well, I wasn’t gonna take anybody else on right now, but I like what you do, so I will take you on.”

The first thing that he said to do was to come to the San Diego Comic Convention. This was about ’88, ’89, something like that, and the convention still took place in the hotel. It was big, but nothing like what it is now. In fact, it was still a comic convention. That first year that I went down, I met Matt Wagner, Diana Schutz and Bob Schreck, and a woman by the name of Barbara Randall, who was an editor at DC Comics. It turns out that I showed portfolios around to everyone. I don’t think that Diana or Bob knew me, but we got along pretty well and we had a lot of similar tastes. They were interested in my work. Matt did know my work; he knew Thieves' World and liked it. Grendel was part of the boom, and it was a pretty big alternative comics hit at the time. Barbara did not know anything about me, and I didn’t have anything that was mainstream to show her, but she liked it well enough to show it to a writer that had been kind of forced upon her by Jenette Kahn. Now, Jenette Kahn was the publisher of DC at the time, and she really wanted to get a kind of Hollywood connection going between DC and the movies. So she reached out to a guy named Jeph Loeb, who was I believe writing a treatment for a Flash movie; that eventually became the Flash TV show. He was no longer involved with it by the time it got to TV. She knew that he was way into comics, and that he had a certain name in movies. He’d directed Teen Wolf, he’d directed Commando.1 So he had a certain cachet that way. Prior to my meeting Barbara, he’d made a deal with DC to write Challengers of the Unknown, and they were looking for an artist. Now Jeph will say that he had no history with the Challengers, and when he looks at a lot of the work, he couldn’t tell them apart, except for the hair color being different. But he wanted somebody who could individualize people, and when he looked at my work, he said, “Well, he draws ugly people, but they all look different. So yeah, let’s go with Tim.” For years, that was how he classified me. He said I drew ugly people.

Jeph and I are really different as people, but are very, very close friends. So it was one of those magical things that happens every once in a while. I’m not quite sure how it happened. But that’s how we got together and then became friends, over the course of figuring out how to not drive each other crazy. I couldn’t be more grateful for that. That’s how I met Jeph, and that was the next step, right after Thieves' World. It was Friedrich, San Diego, Barbara Randall and Jeph and Challengers. But that also was where I met Diana Schutz and Matt Wagner. That was my career for the next 10 years, all from one San Diego. Pretty great. And the next San Diego, after we did Challengers, I was there with Jeph, and we met Jack Kirby and gave him a page from the book, and he couldn’t have been more gracious. We’d already been getting a ration of shit from people who were old-time Challengers defenders. Neither Jeph nor I had … especially Jeph — I was a Marvel zombie, and Jeph knew more DC stuff but he did not know the Challengers. And a lot of people thought we were disrespecting Kirby’s work by doing what we were doing. And what we were doing was really essentially not paying much attention to what Kirby or anybody had done with Challengers afterward. We were a part of what was going on with comics then, but we were just wildly experimental. So there were a number of people at DC, we learned later, that didn’t like what we were doing and thought that it was disrespectful to Kirby. Which, of course, horrified Jeph. We never would have wanted to do anything like that. So the idea that he was very gracious toward us when we met him … He of course had no idea what we were doing. And in fact the main thing that he said: He looked us directly in the eye and said, “I just hope you’re following your own vision and you’re doing what you feel needs to be done. You’re the artists in that way. You’re not just looking at my work, or somebody else’s work, and trying to ape that.” I’m sure what he was referring to was that he knew he was somebody who had influenced many generations of people, and that, especially at Marvel, he had been somebody whose work had been pointed to and used as a house style for other people to follow, and he just wanted to say, “Be creative, and go off and do your own thing,” as he’d always done. That was exactly the right thing for him to say to us at exactly the right time. It was very powerful, very freeing for us. So we always point to that, whenever anybody has come to us and said, “You’re screwing Kirby.” I’ve rarely seen Jeph tongue-tied around anybody, and he was tongue-tied around Kirby.

You mentioned that some of the people at DC felt your Challengers work was disrespectful to Kirby — were any of those people with the company when DC was cutting the head off of Kirby’s Superman in Jimmy Olsen and replacing it with Curt Swan’s?

Not that I know. [Laughs.] Actually, and I don’t know this, I’ve only been told this. Nobody ever came up to me and said, “I have a problem with what you’re doing.” In that respect, it’s all rumors. I think Mark Evanier did a wonderful job on his book on Kirby. It’s extremely well researched and a fair overview of his career. I was told [Evanier] was one of the ones who was upset. He’s never said anything to me. I have known him on and off through the years. I can easily see somebody who is as fond of Kirby and his work and his legacy and was as close to Kirby as a person as Mark was might be sensitive to the kind of bastardizations that have come along, say certain things that over time seem less important and are just mitigated by circumstances in time. My very, very limited relationship with Mark is nothing but cordial and respectful and I certainly admire his relationship with Kirby and his legacy of chronicling and writing about Kirby. But at the time, as we were trying to make our way in the industry, hearing about it, whether or not it actually happened, was hurtful.

Did your Challengers work come before your Grendel work?

You know what? I have a hard time remembering that, too. But it’s right around the same time. Let’s say the first — what? — three or four years after Thieves' World there were a number of things. I did a lot of short work for hire and stuff. Some of it was Challengers, some of it was for Comico, who was the publisher that Diana and Bob and Matt were working for. That was Grendel, but it was also something called Amazon. Which was a three-part limited series that I did with Steve Seagle, who was a young writer at the time. That’s about to be reprinted by Dark Horse actually. I’m doing new covers, to make three separate issues and then a collected edition, recolored by Matt Hollingsworth. But all that happened within three or four years after Thieves' World. I don’t remember exactly what order. My run on Grendel was, I’m pretty sure, after Challengers, but it would have been right after Challengers, and it was about seven issues. I know I was still talking with Jeph through that, because he would give me shit about it periodically, and “When are you going to come back?” or “When are you going to be able to start?” However it went, we were together again.

I became pretty good friends with Matt [Wagner], and we would sit together at conventions. And he had a rabid, and still has a rabid, following. I remember sitting in San Diego, sharing a table with him, through his generosity, and people walking over me to get to him, and ignoring me. Through that, we became good friends, but also through that, I learned how to behave as a professional at conventions. Matt is great with the fans. really very genuinely friendly, very genuinely interested. We’re still close friends. And the idea that people would ignore me to get to him, never for a minute, would have bothered me. I’m just not built like that, for whatever reason. And so fame or acclaim never was a driving force for me in that way. All I ever wanted to do really was to have freedom to do creatively what I wanted to do, and fame and acclaim helps with that — it translates to money for the publishers, and therefore they ask you, or allow you to do other stuff. Matt was a real mentor and pal through my first five years, and he could not be more different than Jeph. He’s much closer to me in demeanor.

That’s the second time you’ve mentioned, even though you and Jeph are close friends…

How different we are? He’s from a well-to-do family in suburban Connecticut. I’m from Seattle. My father was an English professor at the University of Washington, and so I’m from an educated liberal household in an educated liberal city. Jeph is driven by success in its many permutations; how people think of you, how people don’t think of you. Money, freedom, constraint, all that stuff. All those things are more important to Jeph than they are to me. Not that they’re unimportant to me, but they’re driving forces to him. He’s a more intensely upfront person than I am. I think most people, if they met me, would describe me as more accommodating or laid-back or something, which is not entirely true. Which is one of the ways that our demeanor can be quite different, yet we can end up being close. We’re both very opinionated, articulate, interested in arguments, and interested in opinions. And we have, not entirely, but very similar tastes. We are both very interested, predominantly interested. in many ways, in pop culture, in all forms. We could talk forever about movies and comics, things like that, or music. I don’t listen to much contemporary music, but we could talk about the Beatles forever. Stuff like that. I’m 52; he just turned 50. So that’s our era. He’s more obviously intense than I am. My intensity comes out in different ways. He was once described as: “The minute he walks in a room, everybody knows how he’s feeling, even if he doesn’t open his mouth.” That isn’t me. So there’s an overtness in Jeph. He’s certainly one of the smartest men I’ve ever met. But by far the funniest, most charming man I’ve ever met, if he wants to be. [Laughs.] Look, I adore him, but I know that — and we figured out intuitively pretty early on — that in our partnership, one of the things that benefited both of us was a kind of good-cop/bad-cop, and I was the good cop and he was the bad cop. He didn’t care about expressing himself. I was always more shy about it. And so he knew how to play that, intuitively. And he knew how to take advantage of the fact that I was perceived as the artiste, and him the commercial aspect of the team. I can’t be commercial. I’ve tried, every once in a while, and failed at it. It’s entirely too limited to stick Jeph in a just commercial box, but he was happy embracing that, as that side of the duo, for him and me. I admire his ability tremendously, and I love him as a guy. But we’re really … We like being different too. I know I don’t have anybody else like him in my life. Never met anybody else like him.

You were talking earlier about Grendel. It seems there are some parallels between you and Matt Wagner, both coming from the black-and-white indy arena around the same time and moving into mainstream work.

But he was successful at it and I wasn’t. [Laughs.]

But the two of you had an appreciation for mainstream superheroes. And you were unapologetic about that and unafraid to inject that into your work.

Absolutely. It always seemed, for both Matt and I, silly that anybody would get all bent out of shape about feeling like you had to make a choice between mainstream and alternative. It’s telling stories with comics; let’s have fun. Movies are a good analogy to that. Just because you like art-house films doesn’t mean you can’t like a thriller. Just because you like a thriller doesn’t mean you can’t like an art-house film. And then how cool is it when something like Terminator 2 comes along and you go, “Well, that’s really smart.” Or The Bourne Identity — that’s a really smart thriller. It has all the qualities you might ask of any movie, but that you usually don’t get in a thriller. Yet you can do it, and it’s a thriller, and isn’t that cool? Shakespeare in Love is really a very mainstream movie, and it’s kind of not at the same time. At it’s heart, it’s a mainstream movie, except it’s an Elizabethan comedy. You wouldn’t really go in and pitch that as a mainstream movie.

So Matt and I are very similar, absolutely. Jeph never really saw the appeal of smaller stuff. Although as a reader, he was a really big fan of things like Reid Fleming: World’s Toughest Milkman. Things like that. He would read other stuff, and we would buy other stuff. But he never had any interest in creating, or being a part of creating, anything other than the biggest thing he could do. That’s why, when he eventually did Hush with Jim Lee, it made perfect sense to me. And there was part of me that went, “Well, thank you for spending time with me. Now you can do what you really wanted to do.” Which again is too limiting, and not true. But it made perfect sense. He had a great time doing it, got a lot of acclaim and made a bazillion dollars and it was great work by him. I was really happy for him. But that’s not Matt and that’s not me, though we’ve both done Batman work.

Was there a point at which, like Matt, you considered writing your own stuff, or even going the self-publishing route like Dave Sim, or were you always just focused on the art?

I was always just focused on the art. I never had aspirations or ideas about writing. I’m not sure why. I’ve been recently looking at that and trying to break that down. If I can find a way to write, to be creative with that, I’ll start from scratch on my own. But no, I was always content to not write. It wasn’t really a consideration of mine. Through the years, it became a little bit more of a consideration, just because you control what you’re doing. So it was curious in some ways that I hadn’t considered it earlier, because I am as much of a control freak as you can be without writing your own stuff. I have opinions about what the writers that I work with do. I insist on having input. I ink my own stuff, partly because I can’t stand the idea of somebody else going over my art. Even though I don’t color or letter, I work with Dave Stewart and Richard Starkings, give notes to each and want to see what they’re doing before it goes off to the publisher. Things like that. But it is curious. It never occurred to me to want to. I always just thought, and in some ways still do think, that I don’t have that writer gene. I tell stories in a different way. I shape things. I know I can’t color. I think I could letter, but I don’t have any interest in getting more disciplined about it. I have lettered before. I don’t know what kind of writing thing I have in me, or don’t have in me. But it’s never been a driving force to get better at it or to explore. Until recently. Now I’m thinking about it, not because I have ideas, but because I want to control more stuff, shape my career a little bit. But that’s something we can talk about later. I didn’t look at Dave Sim and Matt Wagner and go, “Yeah, that’s exactly what I want to do.”

Billi 99

One of the titles you worked on early in your career was Billi 99. I suppose that’s from the period in which you were working in indy comics and…

… trying to break in. Yeah, it was. It was right before working with James. But it was definitely in my head that the city that Billi lived in was Gotham City, that sort of … not post-apocalyptic, but near-future, run-down urban landscape. I was paid $110, for penciling, inking and duotoning a page, and it was four 48-page books. So there was a lot of work. I obviously did it because I needed the money. But it was an incredible learning experience, as well, and I absolutely had in my head that it was gonna be a strong portfolio. It was only successfully a portfolio piece for one person, but that one person was Archie Goodwin, and that was all that mattered. I was living in Seattle, and it was written by a Seattle woman by the name of Sarah Byam. She was a bleeding-heart liberal, as am I, but she was more bleeding, and wanted to tell stories that were about that. That really doesn’t drive me, but I was certainly OK with that, as long as there were visual things that were cool and fun. And there were in Billi. It’s unlike anything else I’ve ever done. I’m quite proud of it. I was glad that Dark Horse reprinted it. I was glad to do a new cover for it, and be involved in some of the design of it, things like that.

And I learned an awful lot doing it. I did it all with the brush, I didn’t use any pen. That was as an exercise. I chose to use duoshade paper. (It’s a chemically treated piece of paper that has visible but not reproducible lines or dot patterns on it. You buy the paper with a liquid solution that you can paint onto it either with a pen or a brush. And when you do that it brings up the dots or the stipple or the line. So it’s like using Zipatone, except you don’t have to cut it out and stick it down. It’s much more creative, because you can use it just like ink, except you’re getting different patterns. And you can either have one pattern or two patterns, and what I chose to use was two patterns, so there were lines going one way and then lines going the other way — so it’s a crosshatch effect. Two shades of gray, and then there’s a black and a white, and it reproduces much cleaner than ink wash. I think most people are probably familiar with it from editorial cartoons, but it’s been used in comics for a long time. It does not, in my opinion, reproduce very well with color over it. So it’s much better than just a black-and-white piece of art. John Byrne used it a lot in some of the stuff that he inked later on in the ’90s, all of which looked comparatively ugly. Every once in a while, people would try to put color over it.) That’s how I did it. Again, it was an attempt to make it look gritty and urban. I had a lot of fun doing it, and it got the attention of Archie.

Now Archie, I think by the time I met him he had already been sick, but was in remission. He eventually died of cancer while Jeph and I were doing Long Halloween, years later. But I’d known Archie’s work, never having met him. I knew his work on the Warren comics, Creepy and Eerie and Vampirella, in the ’60s and early ’70s. Along with the Marvel comics, those were my biggest comic influences, growing up, just by virtue of the fact that they were black and white and gray, I loved that. And then they had giants of the industry, like Alex Toth and Neal Adams and Angelo Torres, working on them; Frazetta was doing covers. It’s just amazing to think about it now. And for a while, each issue had six or seven stories in it, and for a couple of years, Archie wrote every damn story and was the editor, and he was like 22 or 23. Just spectacular and quality work. I knew it, intuitively on some level and then recognized it more as I got smarter about such things myself, he wrote towards the strengths and away from the weaknesses of the artists that he was working with. And that’s a really rare thing in the industry. It sounds like it ought to be fundamental, but it’s not. Writers in comics tend to write what they’re going to write, and the artists sink or swim on their own. It’s one of the things that makes Jeph as good as he is, because Jeph writes towards the strengths and away from the weaknesses. If he’s working with Jim Lee, he wants to write a great Jim Lee book. If he’s working with me, he writes a very different thing. Archie was like that. He also was a tremendously generous and smart and dryly funny person. He grew up in Oklahoma, and that somehow seems to make sense in some way. [Laughs.] A very gentle soul. And I know that he was quite a talented artist in his own right, and he obviously worked with many artists, but he was more of a writer. And he meant a great deal to Jeph, in that he was not intrusive, he somehow knew what you wanted to do. He had a talent for figuring that out and helping you do it. And letting you do it. Each of us, he would do things like, after he turned the work in, he would call and say, “I love the way you had the cigarette fall out of that guy’s mouth on page 19.” That would kind of be it. But it was detailed enough that it would let you know that he’d really looked at what you’d done. That he’d appreciated what you’d done, and by virtue of what he’d picked out, it helped you shape a way to go and a way not to go. The conversation may not be more than 10 minutes long, but it was just so helpful and so great. He was just an amazing guy. I know of no one who has a bad word to say about him. Personally, he meant a great deal to me, and, if anything, he meant even more to Jeph. And the idea that he let me work with James and then let me do another Legends with Jeph when no one had ever done more than one before. My career would be who knows where without him.

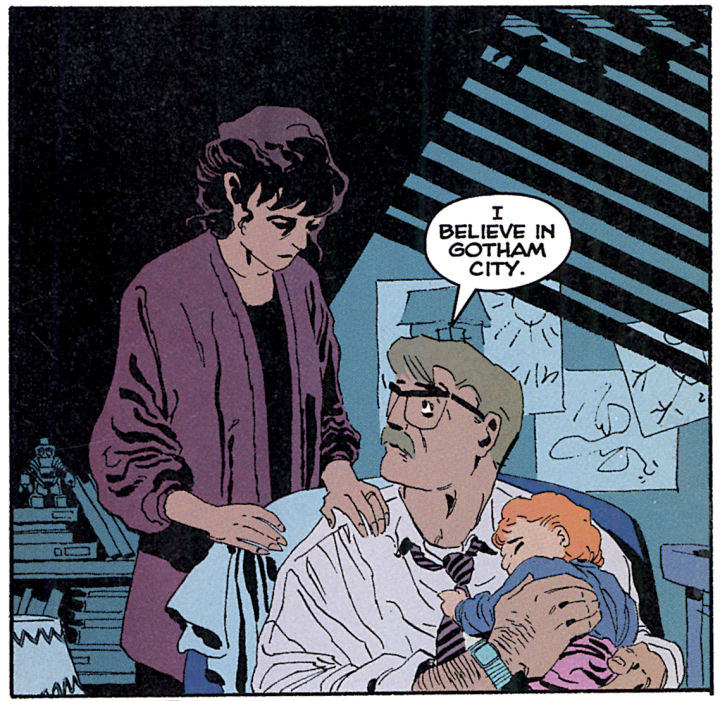

After Challengers of the Unknown, you got more heavily involved with DC, and with Jeph. I first discovered your work in a Legends of the Dark Knight story you did with James Robinson — “Blades.”

After Challengers of the Unknown, you got more heavily involved with DC, and with Jeph. I first discovered your work in a Legends of the Dark Knight story you did with James Robinson — “Blades.”

I met James at [the San Diego] Comic-Con through Matt, I think. James hadn’t worked very much in comics, but wanted to very much. He knew Matt better than he knew me. So I knew Matt first. He actually was one of the people who didn’t like what I did with Challengers. [Laughs.] Because he was a big DC fan and thought it was a little disrespectful. But we got along as friends, and we talked periodically on the phone. At one point, we were talking on the phone, and he told me that he had sold a script to Archie Goodwin for a Legends of the Dark Knight story. I said, “Do you got an artist?”

He said, “No, I don’t.”

I said, “What about me?” And that was “Blades.” When I’d finished that, it turned out — I didn’t realize it at the time — Jeph had been jealous. Jealous of both that I had gotten to work on Batman, but also that I’d worked with another writer. He’s very possessive in that way. But when I was done with “Blades,” Jeph — really for the first time — expressed his desire to do a Batman. So I called Archie and said, “Could I possibly do another one of these with Jeph?” And I didn’t really know what to expect, because no artist had really ever done more than one arc on Legends. So I thought maybe that was a rule.

But Archie said, “Yeah.” And so the first Halloween special began, as a story arc in concept, on Legends.

The Long Halloween

How do your collaborations with Jeph compare to those with other writers? On “Blades,” for example, your panels were smaller, tighter than on your Halloween specials with Jeph. Was that because Jeph, having already worked with you on Challengers, knew what to expect from you, and gave you more room to play with?

Yes, very much so. James comes from the Alan Moore school of scripting. One of the first things he said to me was “Feel free to modify or change or ignore. But I’m gonna put it all down.” I’m not like Alan. I don’t know if you’ve ever seen an Alan Moore script — 10 pages to describe a panel, right? James comes from that school, but he wasn’t like that. James said to me, “Feel free,” but I didn’t believe it. It was also early enough in my career that I didn’t feel that I could take those liberties, either with him or with the public. I wasn’t very bold in that way. But regardless, there was still an awful lot that had to happen on a page. Maybe I didn’t have to draw it exactly the way he described it, but there were a lot of things that had to happen on each page, and there were quite a few panels, and a lot of work. It was hard to find a way, for me — in the way that I draw — to feel free and express what I think I do best. That was one of the things that became magical about working with Jeph, what we learned to do through the Halloween specials. I really felt by the end of Long Halloween that we had it down.

James loves comics, certainly. But he conceives of comics in a different way than Jeph does. And one of the things that Jeph first said to me was that he believed that comics were a visual medium. His job was to push that and to allow that or encourage it. When I first met him, he had a writing partner in movies. And this writing partner was the more rounded one in some ways. Jeph described it to me once by saying he’d be sitting in a room with him, and he’d say, “Well, why can’t we put the camera on the end of a broomstick and throw it through the window? Why can’t we?” Then his partner’s job would be to say, “Listen, the reason why is because …” So he was gonna push things, and that’s what Challengers really was: How much can we fuck around with the medium and still tell a story? And a lot of those visual ideas are Jeph’s ideas that I would then play with and add my own flair to. James had a much more word-heavy, standard way of approaching a page or approaching a story. And I would talk with James about it.

When we were working on Amazon, Steve was the first person that wrote a script that was about three or four panels on a page. And it was incredibly fun and freeing and open, that I could screw around with that in various ways. It was really enjoyable. Ever since then, whenever I’m working with anyone, I’ve said, “Can’t we just have three panels on the page?” [Laughs.] And every writer has always said, “No, we can’t. I can’t possibly tell a story in that few panels.” Which is one of the reasons why I loved New Frontier. Because Darwyn said, “Yes, you can. Let me show you how you can do it.” Regardless, I had those conversations with Jeph and I had those conversations with James. And Jeph kind of got it, and figured it out in different ways.

Does Jeph give you more than what’s traditionally referred to as “The Marvel Method,” with just a basic plot on a sheet of paper?

It isn’t anymore. But it was in the beginning. We’d throw around a lot of different ways of working in the beginning. Partly because we were both so new to the process and new to each other. But Jeph had never written a comic before working with me. And there was a lot of artwork that got thrown away, that I did thinking that we could be more equals and more back and forth. Well, the problem is, his stuff is words, but mine is a daylong drawing, right? If he says, “No,” or what I’ve done gives him an idea for something else that works better, I’ve still spent an awful lot of time doing something. Jeph once drew a drawing in a sketchbook of mine that was 24 panels, like a comic page, and 23 of the panels are the same drawing — of just a frowning man’s face with one word balloon saying, “No.” In the last panel, he’s smiling, and it says, “Yes!” The caption for the page is “The way in which we work — by Jeph.” It was pretty fucking true. There was an awful lot of that early on. He now writes a full script, not Marvel style at all. For a number of years, all the Halloween specials were produced this way. By the time we got to Long Halloween it wasn’t any more. But I think all of the Halloween specials were five- or six-hour phone calls, where he would get a yellow legal pad, and take a credit card, and draw a rectangle on the legal pad, and the rectangle would be a comic page. He’d divide it up into panels, and he’d make little notes and call me and describe the book to me. And I would do the equivalent on my end, drawing rectangles and making notes and saying what they were. But it was a really good way for us to get to know each other. For us to get closer, and for us to just sort of bullshit about what he meant, and then my interpretation of what he meant, and play off each other in that way. In the beginning, he always used to cast actors as characters. I know that each one of the Challengers had different touch points, either actors or characters — Mr. Spock, as opposed to Leonard Nimoy, or Ed Harris in The Right Stuff. Miller and Mazzucchelli were big, big influences early on. But other comics, dating back from the mid-’60s on, were also touch points, because we remembered when Neal Adams did that or Jim Steranko did that. We’d just riff on that. It’s very seamless now. It took a long time to get there, but it was worth it.

Synthetic City

Around the time you were working on the Halloween specials for DC, you did some work for Image, following Jim Lee on one of his titles — Deathblow.

It was between the first and the second Halloween special I think. I know that the way I drew Batman in the second one — he was hugely muscular and had a tiny head — I know that was because of my drawing Deathblow. It’s all comical now to me and it’s certainly not how Batman should be drawn, I think, but there was a lot of stuff, just visually, in Deathblow that I like a lot. It was a lot of fun to play in that faux Sin City that Jim had established. I like the high-contrast look, and I’d never exaggerated the figure in that way before, so that was a lot of fun to play around with. It was a lot of hard work because the writer, Brandon Choi, was always way behind deadline, and they were on me a lot about trying to make up that time. If that were to happen now, I’d go, “Well, that’s not my problem.” But my personal record is that I penciled 11 pages in one day. Now the pages were all bog sort of splashy things, and a lot of the drawing was to be done in inks, so it’s not as though these were really tight pencils or anything, but still they weren’t thumbnails — they were actual pencils. [Laughs.] I made the mistake of telling Jeph that once and now he gives me shit about it all the time. “What do you mean you’re not done? I knew a guy that once penciled 11 pages in a day!”

“That guy is gone.”

So anyway that was not a whole lot of fun, chasing those deadlines. The story wasn’t terribly interesting to me, and I was aware that working in a world that wasn’t really my world, from the story to the character, the company, I wasn’t really invested in what I was doing in the way that I ideally would like to be. I was also really aware that whatever I was doing, sales of the book were going down and down and down. A lot of that was because it was coming down off the Image boom winding down, and I wasn’t Jim fucking Lee, and was never gonna be, right? So certainly I didn’t have then, and even to this day I don’t have the kind of cult of personality that Jim has, and rightly so. Jim’s work is remarkable and very different than mine, and much more commercial than mine. I think we’re both comfortable with our own places in the world. I certainly am. But I was aware that I was hired to do a job, and the sales were going down, and that was a drag. But there were also a lot of fun things about it, just in relation to “Here’s a drawing that I have to do.” I liked imitating the Sin City look. I liked the exaggeration I could do, that I was encouraged to do, all that kind of stuff.

When Jim Lee first came out with Deathblow, was Frank Miller critical of it?

Here’s how it went in my experience: Bill Kaplan was Archie Goodwin’s assistant editor when I did the first Halloween special, and he was hired away from DC by Jim, to come work at Wildstorm, or Homage at the time. But when he was still at DC, Jim’s work on Deathblow had come out, and we both kind of giggled. Here was a guy who was the most commercially successful artist in comics in 15 years, who was purposefully changing his style to imitate another artist, and we didn’t quite get why. When Bill moved over to work with Jim, he called me. We talked, we were friends, and he said Jim just really loved what Frank was doing, and as a kind of side job Jim wanted to try and work in this other way. He was inking himself. The storyline was gonna be very different — it was this mystical military thing. But he was just in love with it, and when Jim decided that it was unrealistic for him to continue to pretend that he was gonna continue to draw this book on anywhere near a regular basis, he said, “We should get somebody else to do it,” and I don’t know who suggested me. But the idea that somebody whose natural style was closer to Frank’s Sin City work should be the go-to, and I was told directly that the idea is to draw as close to Sin City as possible. That’s what Jim’s original concept for the series was, and that’s why I in particular was hired. I was uncomfortable, and in fact, as I said, I had laughed with Bill about what Jim was doing, even though I thought the work was pretty good, but I didn’t get it; it sounded funny. I was told that Jim and Frank were friends, that it was acknowledged to be OK and sort of a winking homage to Sin City, and that everything was fine.

I’ve never heard that Frank had a problem with what Jim was doing. I did hear later that Frank had a problem with what I was doing. I heard that because he wrote about that in print, on a letters page in an issue of Sin City. I was upset about that. I was upset I guess for a number of reasons: one, that if he had a problem, all he had to do was say something, either to Jim or me, and I would have worked differently. The other was not only did he not do that, but he did it in print. And he’s Frank Miller, he’s the biggest guy in comics — he was then, he is now. That carries a fair amount of weight. To this day, I get shit from people, not a whole lot any more, but I get shit from people about that. I just think that was very poor form on Frank’s part, and unfortunate. Partly because it was detrimental to my career for a little while, but also because I’d been having a good time thinking we were all kind of laughing about this, and I was carrying on a tradition of “Don’t we all love what you’re doing, Frank?” Then to be taken to task for it was disappointing. People in my corner, as it were, always leap to “Oh yeah, like Frank invented noir or a high-contrast look. What about Will Eisner?” He gets to do it. There was a direct line to what he was doing on Sin City to what Jim was doing on Deathblow to what I was asked to do. I don’t want to defend it in those terms.

It is, interesting however, that Matt Wagner pointed out to me the job that Jim Steranko did on an adaptation of a Peter Hyams movie called Outland. It more than anything else is a direct precedent for the high-contrast Sin City look, much more than Eisner or anything else. It’s pretty remarkable, and I hadn’t really put those two things together. Matt was the first one to put them together. So there’s that. I have no interest in defending what I was doing in artistic terms. It’s just too bad that if Frank had a problem he didn’t say something other than in print. But I don’t know if Jim took any shit for it. If he did, I just don’t know.

With the Halloween specials and The Long Halloween under your belt, did DC want to pair you with other Batman writers?

No. I did work with Alan Grant a little bit … I worked with a few other people. But it wasn’t on the part of the company. Jeph has a really, really good business sense, and one of the things that he has always done is long before we are done with the current project, he is thinking about the next thing we might do, and starting to formulate that, and starting to sell that to DC, or now Marvel. One of the things I learned over the last two years, and feel very strongly now is that from the Halloween special on there was a concept of us as a team, that when the two of us worked together you kind of knew the story you were gonna get, regardless of the character or the particular story that we were telling. You could rely on it in a certain way; there’s a Loeb-Sale imprint. I think that’s really valuable. I think other people, from Grant Morrison and Frank Quitely to Lee-Kirby, whatever, different people have different favorite teams. It’s one of the cool things about comics. Jaime Hernandez or Matt Wagner, I’ll follow what they do, just because I’m a fan of theirs. I really do believe there’s a Loeb-Sale … I can’t think of a better word than imprint, although that’s so corporate. There must be a more creative word that escapes me. [Laughs.]

I think you’ve described it before as a sort of boiling down of characters and their mythology to their basic elements, their essence.

Right, that’s our basic approach. I’m just trying to think of what would be a good term for what it is. But yes it is. Partly because of our age, but also because of our demeanor, and the way we look at comics. I mean Jeph could live in the Ultimate universe. I could never do that. It would drive me insane. So he can work in a number of different ways. When we work together, what we bring to it is: “OK, what was really cool about these guys that made them stick around for 20, 30 years?” Or in the case of Captain America, 60 years. That’s the kind of stuff that we want to do. And tell those stories in a more contemporary way, but not get bogged down with all the bullshit of what’s come to be known as continuity. When I first started reading Marvel Comics in the ’60s, what continuity meant was that you giggled because Spider-Man might go swinging by in the background of a Daredevil comic. Or there would be a team-up every once in a while. And they’d have to figure out how to coordinate those things. At some point, both companies discovered that you could fill a ton of comics by making things more convoluted. It seemed to me that the X-Men office was the first example of that. It made all of that unreadable and uninteresting to me. But they sold a gazillion comics, so you can only argue with it a certain amount, right? It’s just not what I’m interested in doing. In the same way that I like three panels to a page, and I like a high-contrast look in my artwork. I don’t use full bleeds. I don’t break the panel border, either with balloons, or with artwork. I like a cleaner look, aesthetically, and because I am interested in reaching an audience that goes to the comic-book store every Wednesday. I believe that the people who have not grown up reading comics … If, for instance, let’s say somebody loves the new Batman movie, and they go, “You know what? I’m gonna go check out Batman comics. I haven’t seen one in 20 years.” They go and they see there’s a million speed lines and a million panels and a million words on a page, they’re gonna go, “OK, this is too much fucking work.” I know that I look at those pages and I think it’s too much fucking work to follow. I’m interested in being somebody where they can open my book and go, “Well, that’s kind of cool. I wonder what happens next.” I think one of the ways to do that is to not have it so busy all the time. That’s one of the reason I love New Frontier.

One of the theories is that it should take as long to absorb the art in a panel as it takes to absorb the words …

I know that one of the first lessons that Jeph was taught about storytelling — because we talked about it a lot — was that you ought to be able to follow the story without the words at all. Now the words can add a great deal, but in the basic sense, A to B to C is followable without the words. The way that we worked together taught each of us how to get better at that. It’s a different way of describing what you’re talking about. He learned pretty quickly how many words to have in a balloon before the tendency of the reader was “Let’s see if I can skip reading that and still get the gist of what’s going on.” My girlfriend has a 9-year-old boy, and he’s just reading Long Halloween now. I was looking at it with him last night, and he told me he doesn’t read the captions. It doesn’t hurt his experience with the book. Obviously it would enhance his experience with the book, but he’d prefer to do it that way. He could follow the story, he enjoys doing it. Long Halloween is very copy-light, but he’s anxious to get through it. Pictures are what excites him. He is 9, but he’s kind of new to comics, too. And adults can be new to comics, and they’re gonna have a lot of the same experiences, and go, “OK, what do I need to do? What can I get away with? If it turns out I like it, how much more can I get out of it? And will I get more out of it if I read the captions as well?” That kind of thing. But one of the things that Jeph had to learn as he was learning to write comics was how many words and balloons, how many balloons on a page, that kind of stuff. I know that when he would talk to me about working in the X-Men office, he said that they wanted more. That was part of what they believed the imprint of an X-book was. Jeph would joke about inventing the Caption-O-Matic 5000 — “Why use one panel when you can use 20?” That kind of thing. Thank God he could put that aside when he went back to work with me.

Change of Seasons

After the Halloween specials and Long Halloween, were you starting to get a little sick of Batman? Is that what prompted Superman for All Seasons?

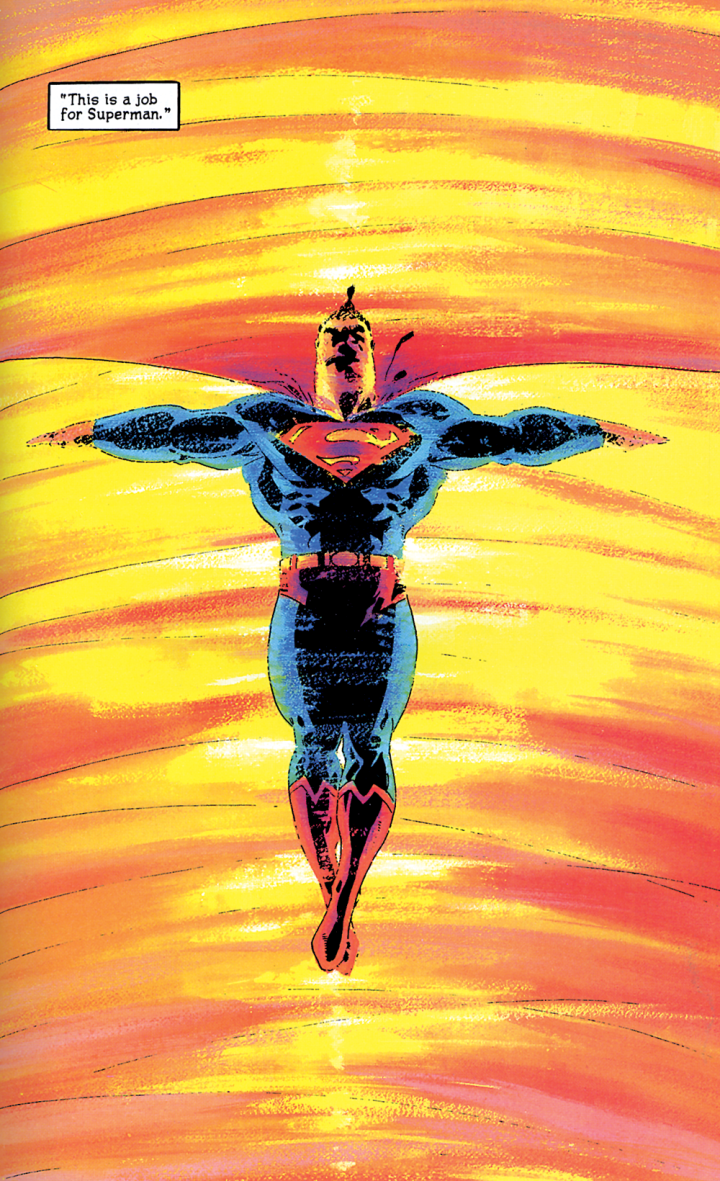

Well, “sick of” is too strong, but yeah. What I remember is that Jeph had always been interested in doing Superman with me. Because he loved Superman, but also because he saw the business sense in it. In my opinion, there are only three real icons in comics, and Batman and Superman are two of them, Spider-Man being the other one. We’ve now done all three, but having done a lot of Batman there was a sense of “Why not do the other one?” I just didn’t see it. I couldn’t feel it. In my memory, it was very quickly that I suddenly did, and I don’t know what prompted it, but I know that my [way] in was influenced by two things. One was Norman Rockwell, and an idea of describing America and goodness via an image of it. So Americana, not America; and goodness as an ideal, something to aspire to, not reality necessarily. And if you’re Superman, you can do a lot more obviously than most people, but you’re still going to be constrained by

what you can and can’t do. The story’s about what you can’t do.

So that was one thing. The other thing was there was a DC Christmas special that was an anthology. Paul Chadwick wrote and drew the Superman story. And this is one of the things that will happen with Jeph and me — we both remembered it, and we’d never spoken of it prior. It’s relatively obscure. It’s not like it was a big hit or anything. It’s about an old man in a car in the middle of winter. His life is in the crapper for some reason. I can’t remember what — I think he’s lost a job. It may be the kind of thing that if he dies, his wife is gonna maybe get some insurance money. He’s sort of doing it for her. But he’s also very sad and self-pitying. And Superman shows up. What he does is, he gets in the car with him, and talks to him, and talks about doing the right thing; and talks him out of killing himself. Then he becomes Superman. He uses his heat vision to heat up the engine block, which was frozen, digs him out of the snow, things like that. But it was about the goodness and the humanity of who Superman is. And I loved it. I haven’t looked at it in at least a decade, and, again, I don’t know the name of the story. I know that Paul didn’t ink it himself, and it’s fairly crudely drawn. But it was a great take on the character. For both Jeph and I, it was a big influence on Superman for All Seasons, as a way of looking at the character, and who he was and wasn’t. Ways that he was special that were not just bouncing bullets off his chest and changing the course of mighty rivers. So all of a sudden — at least my memory of it was that — it made sense to me. I remember saying it to Jeph, and Jeph was flabbergasted. Because he’d been pushing Superman for years and I’d been saying, “No,” and all of the sudden I was saying, “Yes.” He got very excited. It was the only time it’s ever been like this for us — we had this talk, and it was relatively short, but it was clear that he was excited, and that excited me. We hung up and I called him a few minutes after that and left him a message, saying, “I can’t stop thinking about it. I just wanted to call you again.” He called me in a few minutes and said, “ I was just about to leave you the same message.” It was one of those things that just solidified in our brain.

Then the actual process of doing Superman was an entirely different thing. How I was gonna draw it and how we were gonna write it were in flux, and we knew we wanted it to be really different. There was no point to doing it like Batman. The whole idea was that it was an entirely different character, and that should be reflected in both our work. We were at San Diego, and I would describe that I wanted to do the blue-line process, because computer coloring was really crude at the time. I didn’t like any of it. It was like everybody had just learned Photoshop, and they wanted nothing but kick lights and lens flares, things like that, or garish coloring. Jeph really didn’t know what blue-line was. He didn’t know what to expect. So it wasn’t until he saw some sample pages from the colorist that we were working with, Bjarne Hansen, that we were really excited.

To my knowledge, Superman for All Seasons may have been the last blue-line process thing DC ever did, maybe even the last done in comics. There are a lot of registration problems that you can run into, there are a lot of presentation problems that you can run into. But DC was great about it all, and it really, really affected my approach and the look of the book in a very positive way, I think. I’ll always be grateful to DC, Richard Bruning in particular. The headaches that came after that, though, with my approach and the way I was gonna draw Superman, was an entirely different thing. There was a lot of back and forth about that. My idea was that I wanted it reflected in the physicality of Superman that he wouldn’t have to go to a gym to work out. He’s an alien, so he was this kind of giant. The intent was that he looked like he was a corn-fed country boy. But if you don’t do that just right he looks kind of retarded, or slow, you might say. And DC freaked. I think they expected Long Halloween Part 2. And it certainly wasn’t that. And then you’ve got their flagship character maybe looking like a doofus — “What the hell is goin’ on? This isn’t what we’re paying for.” It took a while to calm everybody down and prove to them that we had an idea that made sense. To give them their credit, I didn’t have it quite right at first, and they had a point. He did look kind of like a doofus sometimes. And also to give them credit, they did ultimately allow us to do, and me to do, our vision of what we wanted it to be. But there were some growing pains along the way — all of which, when I won the Eisner for Best Artist of the year, was forgiven. [Laughs.] That was a nice point of validation for me.

After Batman: The Long Halloween and Superman for All Seasons, you and Jeph Loeb collaborated on a third DC series, Batman: Dark Victory. How satisfied were you with the way that project turned out?

I’m in the minority in that I much prefer it to Long Halloween. I know that my work is better. I was a much better artist by the time I got to it than I was when I did Long Halloween. And I actually think Jeph’s writing is better, in almost every aspect. What it doesn’t have is that it’s not the first, and so it doesn’t have the blush of the first, and the sort of groundbreaking quality, as it were, of Long Halloween. Most people don’t look at it in the same way, or consider it the bastard stepchild. But I feel the opposite way about it. There are many points in Long Halloween where I will cringe looking at it, and there are very, very few places in Dark Victory. That’s the thing that I look at most, and think “I can’t believe that I did all this, month after month.” It’s like somebody else did it. It’s that kind of thing.

I resisted doing any story with Robin forever, and I wrote about this in the introduction to the collection. I never liked Robin; I thought he was a dumb character. I thought Batman was essentially a loner, and the idea of pairing him up with some brightly colored kid was just stupid; and too clearly a commercial pandering to try to get kids to buy the comics, that sort of thing. And then Jeph figured out a way to make it make sense to me. That came because I was involved with a woman at the time who had a little kid, and so I was involved with both of them. And my relationship with Trevor, Jeph wrote into Bruce’s relationship with Dick Grayson. Jeph really got it, he really got my relationship with Trevor, and he really knew how to make that make sense with Bruce and Dick. It was a just a whole lot of fun, visually and storytelling-wise. And also it was great to come back to it right after doing something so different in Superman for All Seasons. To come back to Batman really felt like coming home again. I just loved drawing Batman in that world. I hope I always have the opportunity to do that. I just think he’s a really great character, and I think he really fits me, or I fit him, however that works. [Laughs.]

Also, I would say there’s a couple of other aspects to it. My relation with the three other people besides Jeph involved with the creation of that book, Mark Chiarello, Richard Starkings, Greg Wright, deepened while working on Dark Victory. Greg and I never became great friends, certainly not in the way that Mark and Rich are for me, but I had worked with Greg a great deal prior to Dark Victory. Both Jeph and I agreed that we wanted to kind of challenge Greg to work with a different palette on Dark Victory, and in my opinion it’s the best work of his career. It was in fact a different palette, and it was a great one I thought. It’s quite different than Long Halloween. There’s a lot more that I asked him to do, things like color holds, the removing of lines, things like that, as well as the palette he was using. (It may be kind of funny to hear me talk about things like palette given that I’m colorblind, but I can see color, and I can see how things are different. I just can’t really create with it.) I was so proud of him for what he did, and I think it’s really one of the strong aspects of the book. It was the first time that, in working with Richard, we’d used a font that he created based on my handwriting. (Which anyone can go to Comicraft.com and buy, by the way. [Laughs.] It’s called the Tim Sale font, and for $50 you can have it on your computer and use it.) So that was very, very interesting and exciting. My working relationship blossomed into a very strong friendship with Richard, and, most of all, my friendship with Mark and how he influenced and inspired me and broadened my horizon of influence. His knowledge of American illustration really opened my eyes to a great deal. Part of what made it satisfying was that I really felt like I was in a groove and I knew what I was doing, whereas on Long Halloween I was hacking my way through and finally toward the end I’d figured out some things. It had its own kind of excitement but also felt more like work, whereas Dark Victory was more the headiness of “Wow, this is great. We’re really in the groove.” I think it’s the most consistent work I’ve done.

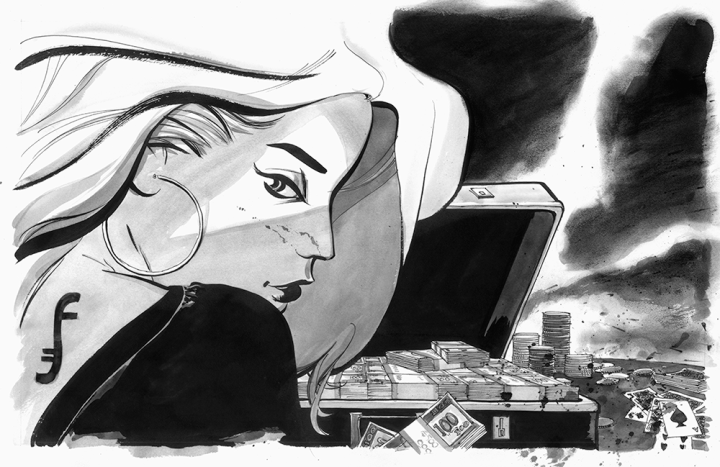

Your third extended foray into the Batman universe was Catwoman: When In Rome. What appealed to you about that project? Was it the opportunity to apply a lighter tone to this sort of material?

Well, no. Because I didn’t know it was going to be lighter when we started it. This was Dan DiDio’s idea. Jeph and I had no intention of doing anything like it, but as soon as Dan pitched it, it made sense to both of us. I remember Jeph calling me and saying, “You know, the fucker made sense. I didn’t want to do it, but it’s too good an idea not to do.” The idea being that there were six months during Dark Victory when Selina Kyle leaves Gotham City and then returns at the very end of Dark Victory. Where’d she go? What’d she do? It’s implied that she goes looking for her own origin, who her father is. She has a conversation at the Roman’s grave at the end of Dark Victory, so that certainly implied who she thinks her father is. What happened was that Jeph’s concept of the story of what she did in Rome turned out to be lighter, and I personally found that much less satisfying than I’d hoped it would be. I’ve spoken with Jeph about this, but it was disappointing to me, that series. I didn’t particularly enjoy Selina’s relationship with the character of Blondie. There wasn’t as much Rome, given that it was set in Rome, as I would have liked there to have been. We go to the Coliseum and we go to the Vatican, and both of those were a lot of fun. I like doing that, I like being in specific places, I like doing that kind of research. You feel a sense of place. But we spent a great deal of time on a boat in the Mediterranean, and that was dull to me. I did like the comic foil of the Riddler. I find him less interesting when he’s actually evil. I like him better when he’s a comedic foil. But I think what Jeph does best is a melodramatic sense of romance and tragedy, and the opportunity for this story to be very strong that way was — I don’t think — ever really reached. The way that he could do it so well, and did do it so well in Long Halloween and Dark Victory with Selina and her relationship with Batman and her own closed-off-ness. Not being in touch, wondering about it, being tortured by her own past, or not knowing — I don’t think was ever really dealt with all that successfully in When In Rome. It was also the first time I did ink wash where I didn’t think it was really that necessary, that it was a commercial consideration as opposed to an artistic one.

I mean when I did Daredevil: Yellow, it was absolutely an artistic choice, because I wanted New York City to be a character in the book, and I thought that was the best way to draw New York City, or it was the way that I wanted to depict New York City. The way that I wanted to depict it was best represented using ink wash, and I didn’t think that When in Rome really benefited that much from it. And it’s a lot of work, it’s a lot of work to do something in ink wash. You’re inking something actually more than twice, so that was draining in a way.

Having said all that, I look back on it and there are some things that I really like a lot. I just didn’t think that it held together conceptually quite as strongly.

Yellow, Gray, Blue

Marvel really seemed to latch onto the approach you took toward DC’s superheroes. They let you apply it to three of their characters: Daredevil, The Hulk and Spider-Man — in the three “Color” books.

Marvel was interested in us working for them, because by that point we’d already done Dark Victory…. The Loeb-Sale way of doing comics, and the imprint of the team, Marvel was interested in doing stories about that. They said, “What do you want to do?”

We said, “We want to tell Year One-ish stories about these characters.” Actually Captain America was always meant to be the fourth. We never got around to doing it for various reasons when we were first over there. As I mentioned earlier, I was a Marvel zombie growing up, Jeph was not. But Daredevil and Spider-Man and the Hulk, they were big shit to me, and Cap was too. Now, there were also other characters that were big shit to me that I don’t really have an interest in drawing, but they were. So I, in some ways, pushed Jeph into it a little bit. He didn’t have a natural affinity or an inclination for telling stories about these guys. He downplays this now, but I remember having a number of conversations that were really pretty uncomfortable with him about “What am I gonna do?” Because it wasn’t just stories of early parts of their careers; we were retelling specific storylines, except for the Hulk. But with Daredevil and Spider-Man we were. Jeph had a hard time figuring out what was his job. He didn’t just want to rewrite Stan, so what was he gonna do? I think The Hulk is the best of the three, best in concept and execution — it’s a purist, original story, a very simple story that takes place over 24 hours. Jeph had a great idea that I believe was entirely original, in that Betty is attracted to Banner and the Hulk because their dichotomy and monstrousness reflects her relationship with her father.

But with Daredevil, he sort of retold the origin in the first two issues, and then wrote a romantic comedy. And I don’t know how good I am at drawing a romantic comedy but I look at that now and just think what a terrific piece of writing that story is. And I worked like hell on it, too. It was in ink wash, and I thought that was the best way of delineating the kind of urban environment that I wanted to do. But it was a hell of a lot of work because of that. You’re essentially not just inking a book twice, but the wash takes a lot longer than the inking does. So it’s more than twice. Spider-Man is the weakest of the three for me, which makes me sad, because he’s really pretty much, at least at the core, my favorite comic-book character. So it’s personally sad that I could never quite figure that out. And part of the reason that I could never quite figure it out is that I like to have a different artistic approach for every character and every story that I do, and I wanted to kind of emulate John Romita on that book, and I just couldn’t do it. I can’t. I worked and worked and worked at it, and I can’t draw as pretty as him. I can’t come close to drawing as pretty as him. I knew I could do some version of Ditko if I wanted to — we’re both kind of oddball artists. But I didn’t want to do that. I wanted to do a very smooth ink line. I mean, everybody that Romita draws is pretty! Well, maybe not the Vulture. [Laughs.] But Peter Parker is beautiful. Not to mention Gwen and Mary Jane. But I think my legacy from that book is that I ended up getting better at drawing pretty girls, to the extent that now I get requests at conventions to draw pretty girls fairly often. So I must have learned something by just staring at Romita’s work for hours on end and trying to do it. But I do think that’s the most derivative of the three that we did. Captain America is going to be its own challenge, but he doesn’t as a character have the same weight, have the same kind of emotional and historical baggage that the others did, either for Jeph or for me. The most baggage is “How do you escape Kirby’s legacy on it?” So far, my work on it has been nothing but fun.

So you’re well into the Captain America series at this point?

Yeah. The idea is that it will be just like the previous three, a six-issue miniseries, except this one is really almost seven, six and a half to seven, because we’re doing a zero that will appear in San Diego. It’s 17 pages, so it’s almost as full. That’s at my request, actually. I wanted bigger, bolder things. It was originally an 11-page story. But then it’s really a teaser, the first issue debuts in October. Jeph and I have long thought that October is our month, beginning with the Halloween specials.

Have you signed any exclusive contracts with Marvel or DC?

I’ve been exclusive for years. I think my first exclusive was going back to DC after the Hulk. Jeph and I went back together. And I’ve just recently gotten out of that contract to come back with Jeph over to work at Marvel. I’ve signed an exclusive with Marvel. Really, on my end, it’s a no-brainer, because I can only do so much work anyway, and if the terms of the exclusive are tied to X, Y and Z projects, and there are things like a signing bonus or completion bonuses, because it’s an exclusive, that’s just all the better. It isn’t like I can do two monthly books, and one is for DC and one is for Marvel, anyway. So what I’m doing is working with Jeph on a number of projects and that’s what I want to do, and if the deals are better because it’s exclusive, then that’s fine. I do have a clause for the TV show, however, so there’s no problem working on Heroes while I’m working for Marvel; and obviously I did that working for DC as well.

You’ve spoken before about how you like to vary your look from project to project. Earlier you commented on some of the visual cues you used for Challengers of the Unknown. I can’t help but wonder what kind of cues you referred to in the subsequent DC and Marvel projects. With The Hulk, however, it strikes me there’s a weird kind of children’s book look to it.

It’s pretty cartoony. Some of that is just my evolution in general in those directions. There’s some Chuck Jones in it.