The Shazam movie prompted a shameless flurry of publishing activity as DC Comics set out to make a quick buck from an old comic book, the one that introduced us to the word “shazam.”

“Shazam” is an acronym, the letters of which stand for a roster of heroes who represent various heroic traits—Solomon, wisdom; Hercules, strength; Atlas, stamina; Zeus, power; Achilles, courage; and Mercury, speed. “Shazam” is also a magic word, which, when pronounced by a teenager named Billy Batson, turns Billy into a super-powered adult named Captain Marvel, who can fly and lift ocean liners out of the sea, and whose body is invulnerable.

But at first—in the initial stages of his conception—the character was quite different.

As concocted in 1939 by Bill Parker, then editor of publisher Fawcett’s Mechanix Illustrated, and artist C.C. Beck, the character was named Captain Thunder, and he commanded a team of heroes, each possessing one of the attributes later combined in “shazam.” The team notion, however, was soon abandoned, probably because of its inherent cumbersomeness, and by the end of the year, Captain Thunder embodied all the traits of his erstwhile lieutenants.

Captain Thunder was to debut in Flash Comics, but another publisher, All-American Comics, had just launched a comic book with that title, so the Fawcett editors tried again with Thrill Comics. That title, unhappily, was too close to another rival publisher’s Thrilling Comics. By the time they resorted to Whiz Comics in February 1940, Captain Thunder had been re-christened Captain Marvel.

The most inspired aspect of the Captain Marvel creation was his being the alter ego of the youth Billy Batson. Young readers would identify with Billy, who was a protagonist in the Captain Marvel stories: a smart, inquisitive and precocious orphan (who, as an adult, works as a radio reporter), he gets himself into trouble by investigating mysteries, and then summons a grown-up version of himself who gets him out of trouble. For any child reading superhero comics, it was a dream come beautifully, simply, true.

Unfortunately for Fawcett, when DC Comics, the publisher of Superman, saw Captain Marvel, it saw copyright infringement (skin-tight costume with cape, invulnerability, super strength, and the ability to fly) and sued to get Fawcett to cease and desist. The lawsuit lasted for the entire run of a catalogue of Captain Marvel comic books (which established Captain Marvel as the most popular of the super-powered heroes of the day, out-selling even Superman). The suit went on and on, back and forth, DC winning one battle, Fawcett the next. Finally, Fawcett gave up in 1953 and settled out of court.

By then, superhero comics were fading in popularity, and as circulation dropped, Fawcett decided to get out of the comic book business. So Captain Marvel disappeared until 1972, when DC Comics, having negotiated the publication rights for the character, brought him back to life, thinking, no doubt, to revive not only the character but also his stunning sales record. For a complex of legal reasons (which we’ll get to anon), DC could not use the name “Captain Marvel” in the title of the comic book, so the book was entitled Shazam, and it has been by that name that most of the subsequent attempts at rejuvenating the character have appeared, albeit with today’s personality-driven superhero formula.

The current revival of Shazam, like all its predecessors, is startlingly unsuccessful. It, like all the others, fails to capture the essential nature of the Fawcett character.

By the summer of 1941, Beck and writer Otto Binder had shifted the character off the center of superhero gravity and started doing more whimsical stories. Before long, a light-hearted, tongue-in-cheek treatment prevailed. And once that set in, the similarities between Captain Marvel and Superman ebbed away into near non-existence, and Captain Marvel emerged as a unique creation, scarcely a copy. So unique that no one has since been able to satisfactorily bring him back to life. But they keep trying.

And in anticipation of the arrival in theaters last spring of the Shazam movie, DC once again attempted to do justice to Captain Marvel.

AND IT HAS, ONCE AGAIN, FAILED as we shall see shortly. But Abrams tried to do justice to Cap by producing a scrapbook, entitled, like all Cap’s appearances since 1972, Shazam, with the subtitle, The Golden Age of the World’s Mightiest Mortal (224 9x12-inch pages, color; the 2019 reissue of a 2010 Abrams hardcover, $24.99) by Chip Kidd and Geoff Spear. Kidd’s byline signals a book that is as much a stand-alone design artifact as a printed source of information or entertainment. And that’s the case here: it looks like a scrapbook. The scrapbook format permits the editors to scatter hither and thither fragments of Captain Marvel’s past, all kinds of merchandise— rings, t-shirts and jackets emblazoned with lightning bolts, wrist watches likewise, figurines, Captain Marvel Club membership cards and letters to members, promotional photos for the Captain Marvel movie serial, jigsaw puzzles, coloring book covers, and on and on—all on loan from the collection of Harry Matetsky.

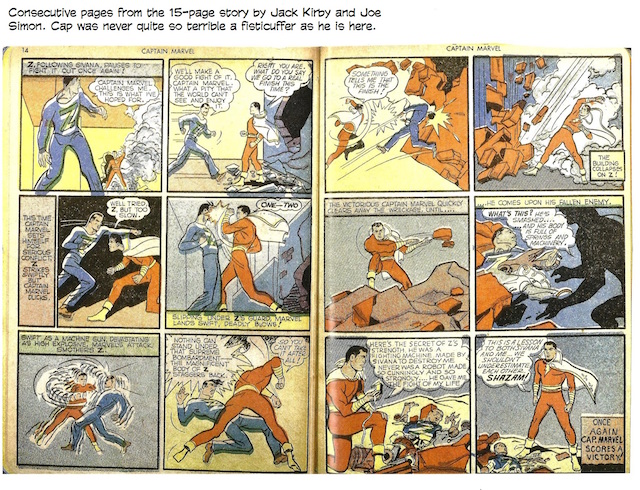

Among the treats herein, a complete 15-page Captain Marvel story by Joe Simon and Jack Kirby. There's not much expository text. But pictorially, the scrapbook seems to cover all the bases. It includes information about other members of the “Marvel Family”— Captain Marvel, Jr. and Mary Marvel but not much about the “fake” Uncle Marvel, the old geezer who goes around imitating the others in his home-made Marvel costume.

When a long-lost sister of Billy Batson shows up, she’s given Shazam powers and becomes Mary Marvel. In those discrete days of yesteryear, her creators made her a pre-teen girl. If Billy becomes an adult when he says “Shazam,” why doesn’t she? The decision was probably a sound one: it enables her writers to avoid the topic of sex altogether, retaining a distinguishing feature of the Captain Marvel books—their absolute sexless wholesomeness, aimed, unflaggingly, at young readers, so young that they may not have heard about sex yet.

Freddy Freeman, a disabled newspaper seller, is a little older than Billy, I’ve always thought. He turns into Captain Marvel, Jr. by saying “Captain Marvel.” We used to get a good laugh out of that: Captain Marvel, Jr. is the comic book superhero who can’t say his name because if he does, he turns back into Freddy. And that’s not all that’s odd about this character, as the editors of the book at hand point out:

“Freddy lives a drearier life than a down-and-out waif in a Victorian novel. He’s stuck with a gimpy leg that requires him to always use a crutch; he’s clad in tattered clothes; and he lives and sleeps in a drafty, forlorn attic when he’s not toiling at his job hawking newspapers on the sidewalk for pennies. ... Why on earth Freddy wouldn’t want to be Captain Marvel, Jr. 24/7 defies logic. ...”

As Captain Marvel, Jr., Freddy escapes all the miseries of his daily life. But he choses to be Captain Marvel, Jr. only when evil strikes others. The rest of the time, he’s just a poverty-stricken kid with a crutch. That’s beyond odd: it’s perverse.

Even odder, we never thought of this while laughing about his name.

The man who drew much of the early Captain Marvel, Jr. oeuvre, Mac Raboy, became as famous as C.C. Beck whose drawing style established the Captain Marvel visual. But I never liked Raboy’s work: he was too fussy, laminating his fine-line drawings of the lithe Junior with far too many feathering and modeling lines. Raboy’s Captain Marvel Jr. had an almost prissy air about him, wholly out of place in an slam-bang adventure story hero. Raboy left Fawcett in the spring of 1946 to assume pictorial command of the Sunday comic strip Flash Gordon.

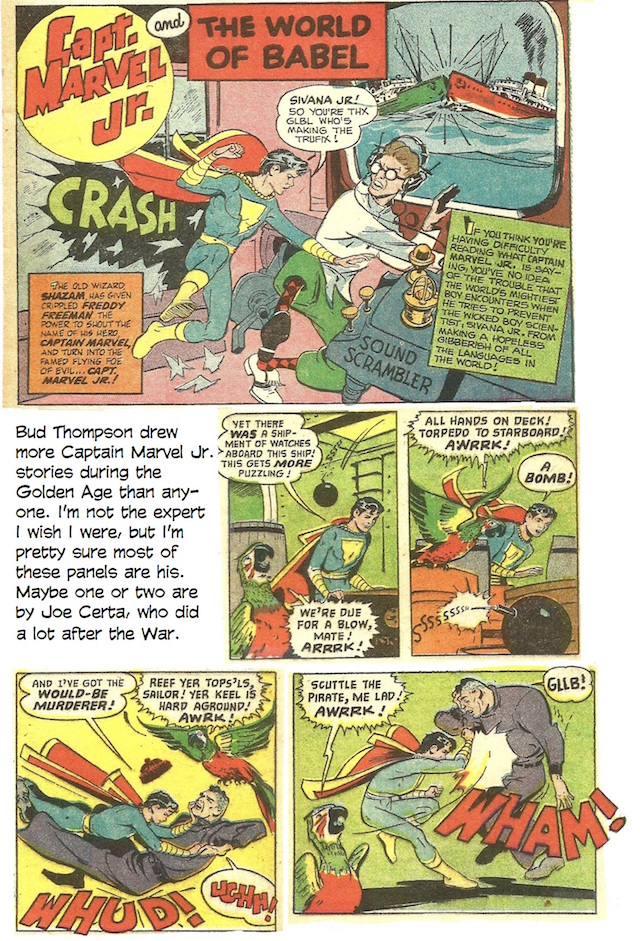

About 30 years ago, I learned the name of another Captain Marvel, Jr. artist—Bud Thompson—whose work I admired for years without knowing his name. His art was cleaner than Raboy’s, his line was more confident, his work less sprayed with feathering.

The Abrams book also includes material from the Spy Smasher’s career with Fawcett. Spy Smasher was Fawcett’s Batman, but I was never taken in by the character. I was taken in, however, by another branch of the Marvel Family.

Fawcett’s Funny Animals comic book starred a cotton-tailed rabbit, Hoppy, who, by saying Shazam, could turn himself into a much more formidable version of himself with a swelling chest, red costume, yellow cape and yellow boots. Captain Marvel of the hutch world, Marvel Bunny, drawn by the redoubtable Chad Grothkopf (who drew the other stories in the books, too).

But I liked two other regulars at Funny Animals more: Billy the Kid, a Western starring a goat; and Sherlock Monk, a detective chimp. We’ve posted nearby samples of the scrapbook content of the Abrams book plus a helping of Funny Animals stuff.

Shazam the Golden Age takes us back to those happy days of the forties, culling from the cultural detritus glistening reminders, for me anyhow, of a long lost youth with comic books. But DC has produced another variety of Captain Marvel’s history—reprints of landmark tales from the last 75 years.

SHAZAM! A Celebration of 75 Years (400 7x10-inch pages, color; 2015 DC Comics hardcover, $47.99) like all Captain Marvel books these days avoids mentioning the hero’s name in its title, but there’s a hugely muscled Cap by Cameron Stewart on the front of the dust jacket and, for the sake of contrast here, a classic Cap on the book cover by Beck, the man responsible for the appearances of Billy Batson and Captain Marvel.

Despite Beck’s formative role in Captain Marvel’s history, only 7 of the book’s 21 stories were drawn by him. The book is organized chronologically, beginning with the origin tale from Whiz Comics No.2 in 1940.

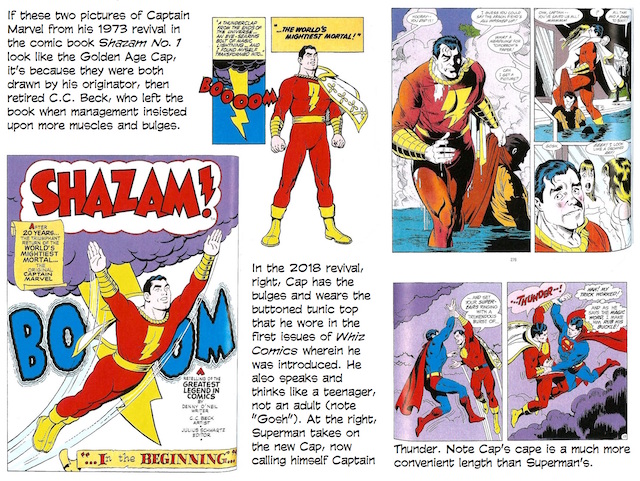

The first chapter takes us from 1940 to 1953, when Fawcett gave up its struggle with DC. The next chapter resumes Cap’s history by reprinting stories from the Shazam reincarnation of the 1970s. Beck drew these at first, and we all rejoiced. But DC wanted a Cap bulging with muscles, and Beck was philosophically opposed to that (he used to write articles scoffing at the bulgey-muscled superheroes) and persisted in drawing Cap in the simple outline manner of his first incarnation. Beck and DC soon came to a parting of the ways, and other artists, led by Kurt Schaffenberger, took over. Before long, Captain Marvel’s physique looked pretty much like every other superhero’s. Still does.

Shazam ran February 1973 -June 1978, and after a brief pause, Cap resumed appearances in other DC titles, represented in this volume’s second chapter with stories from 1982 to 1991. The third chapter resumes the history in 1995 with another Shazam title and then Cap has guest appearances in other titles, ending in 2013. The fourth chapter includes the New 52 version of Cap.

Each chapter has a text introduction by (in order) Richard A. Lupoff (comics historian), E. Nelson Bridwell (editor), and Jerry Orway (comics writer and artist), all reprinted from earlier publications.

The stories brush by various of the classic Captain Marvel tales—Black Adam shows up, Mr. Mind (the all-powerful intellectual worm who tortured Cap for more than two dozen consecutive issues), the Marvel Family, Hoppy, and Jeff Smith’s version of the Monster Society of Evil (led by Mr. Mind).

The original Mr. Mind’s Monster Society of Evil serial with cliff-hanger endings in every chapter ran from No.22 (spring of 1943) to No.46 (spring 1945), 25 issues of Captain Marvel Adventures. That a fantasy involving an evil worm directing the criminalities of monsters would occupy so many pages of a superhero comic book during World War II when exciting patriotic violence had broken out over half the globe may seem odd. Why not attack Nazis? But I think the fantasy was created deliberately to divert young readers’ attention from the real warfare. By the end of Mr. Mind in the spring of 1945, the war in Europe was over, and Captain Marvel could resort to other excitements involving people rather than an insect.

The Mr. Mind series did not entirely displace ordinary criminals and fiends in Captain Marvel Adventures and the other Fawcett titles Cap appeared in, so the strategy, if that’s what it was, wasn’t airtight. But it seems at least possible if not probable.

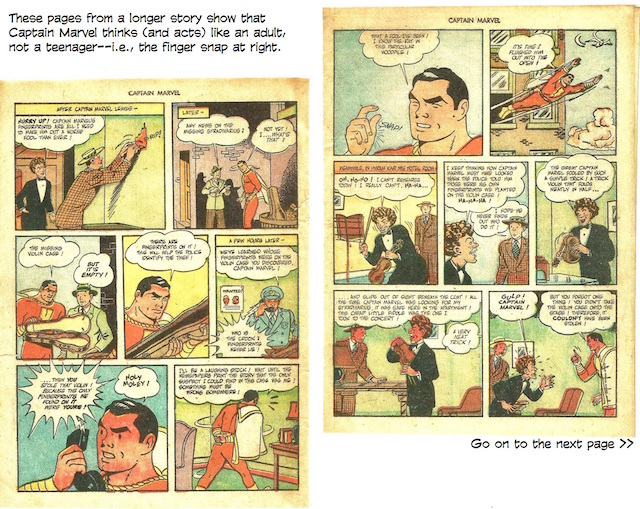

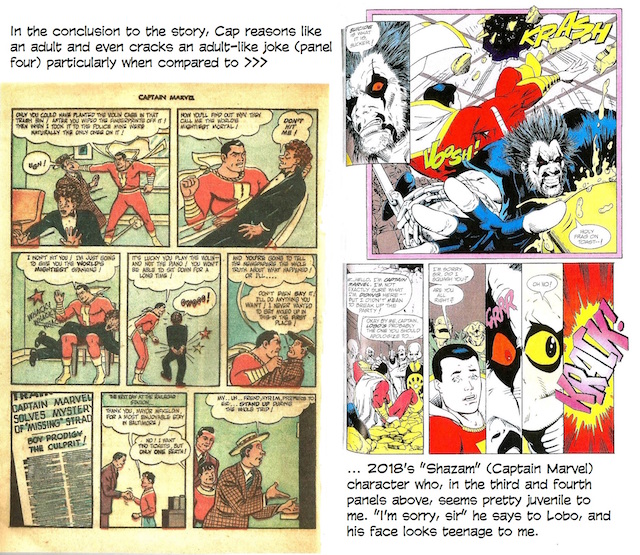

The most serious damage done to the Captain Marvel tradition was the alteration in his appearance, all those muscular bulges. But another change was introduced in the early 1990s. Someone at DC evidently wondered what happened to Billy Batson’s personality when he shouted “Shazam!” and turned into an adult superhero. The brilliant conclusion of this pondering was that Billy’s personality stayed right there, now inhabiting the adult body of Captain Marvel.

So we now encountered an adult superhero with the mind of a 12-year-old. (Sometimes, they say Billy is 15 years old, a somewhat more believable age for a kid with Billy’s record of harrowing exploits.)

Many of today’s comics fans have assumed that Captain Marvel always had the mind and desires of a 12-15-year-old kid. Not true. That’s a modification of recent times. In the olden days (when Beck was overseeing everything in the Captain Marvel universe of a half-dozen titles), Billy’s juvenile personality all but disappears when Cap shows up. That may seem highly illogical, but we all accepted it as normal (insofar as the world of superheroes is ever “normal”).

In any event, as far as I’m concerned, that alteration is the final desecration of the funnybook hero of my youth. Phooey.

All the recent publishing of Captain Marvel stuff was paving the way for the arrival of the movie.

SHAZAM THE MOVIE I haven’t seen. My grandson has, and so has his mother (my daughter), and she says one of the aspects of the character of Billy is that his personality is carried over into Captain Marvel whenever he yells “Shazam!” Too bad. That makes the whole enterprise a somewhat juvenile undertaking.

I’ve read several reviews of the movie, and it doesn’t sound promising. Reviewers generally like the more light-hearted treatment of a superhero adventure after suffering through a score of more serious endeavors in several of which the world as we know it is decimated. Or at least made noisier.

I probably won’t go see it.

But I have read and studied the first four issues of the new Shazam comic book, which seem to perpetuate the ambiance of the movie. The focus of the continuing tale, through the fourth issue, is on Billy Batson and five of his friends—Mary, Freddy, Pedro, Eugene, and Darla—who are all residents of a foster home run by Mr. and Mrs. Vasquez, Victor and Rosa. Just like the movie. The youths are all Shazam-endowed, and when Billy says his magic word, all of the “Shazam Team” appears, each in his/her colorful costume.

Captain Marvel—with Billy’s 15-year-old personality—shows up in No.1 to stop a robbery by some unruly teenagers. Then the six stalwarts go to a deserted train station and take the next train to MagicLand.

Cap doesn’t appear in No.2. But Dr. Sivana, Captain Marvel’s arch enemy in the old Fawcett books, shows up; ditto, Mr. Mind, the worm. And Mr. Batson—presumably Billy and Mary’s father—arrives at the Vasquez’s front door. But he doesn’t appear again until No.4, and even then, we don’t know what he’s doing there.

In No.3, the kids are in FunLand, being led around by King Kid, who hates adults and wants to keep all of our gang in Funland, virtual captives. So Billy shouts his word again, but only he and Pedro and Eugene are transformed; the other three are not in proximity and therefore don’t get the transformation.

Next in No.4, we’re in WildLand and we meet Talky Tawny the voluble tiger in a business suit, another happy relic from the Fawcett years. Meanwhile, King Kid is still on his rampage, and Cap (shocked electrically into unconsciousness) is taken captive; ditto Mary, although she’s in a different place. Freddy and Darla are in WildLand, and Eugene and Pedro are in Gameland. And Mr. Batson is still at the Vasquez’s but is taking his own sweet time telling us why.

On the last page of the book, Black Adam (another of the traditional evil-doers) shows up, muttering imprecations.

I fully expect Hoppy the Marvel Bunny to arrive in No.5, but I wasn’t there to see him. This title is more than mere desecration: it is a wholesale slaughter of all that Captain Marvel Club members hold sacred. And since the whole purpose of the title is to resurrect the spirit of the departed world’s mightiest mortal, I’m fairly confident in saying this re-launch is a thundering failure.

And hereabouts, we’ve posted a few more specimens of the new Shazam for our Marvel Gallery.

AND THEN, FINALLY, comes a Captain Marvel book that does justice to the original creation. Shazam: The World’s Mightiest Mortal, Vol. 1 by Denny O’Neil and C.C. Beck (352 7x10-inch pages, color; 2019 DC Comics hardcover, $49.99) succeeds where other recent publications have failed because its stories are drawn by Beck, the creator who knows and understands Captain Marvel better than anyone. But the stories in this volume are not stories from the original run of the character: this volume reprints stories from Shazam, the comicbook about Cap that DC began publishing in February 1973.

The comicbook is entitled Shazam because it can’t be entitled Captain Marvel, as it ought to be. As most comics fans know, Fawcett, the original publisher of Captain Marvel, was forced out of the comicbook business eventually by DC’s persistent law suits alleging that Fawcett had copied Superman when it created Captain Marvel. Today, with comicbook experts on every block, this proposition would be laughed out of court; but from 1940 to 1953 the courts, unschooled in superhero matters, entertained DC’s persistence until, at last, Fawcett simply gave up, settling out of court and promising never to publish Captain Marvel again.

Then, decades later, along came Marvel Comics, which, believing that the copyright on Captain Marvel had lapsed, began publishing a character called Captain MarVell. So when DC acquired the rights to the original C.C. Beck Captain Marvel, it couldn’t use the character’s name as a comic book title without risking a lawsuit from Marvel. Eventually, DC decided to publish Captain Marvel adventures again, but since it couldn’t use Captain Marvel as the title, it used Shazam, the word that Billy shouts that turns him magically into an adult superhero named Captain Marvel.

To bring the character back to four-color life in 1973, DC had persuaded Beck, who was happily retired to his own bar and grill in Florida at the time, to take up his pencil again.

And Beck did a gratifyingly accurate job of reproducing his Captain Marvel for 8 of the first 10 issues of the new comic book. Eight issues published two new Beck stories and a reprint of a story from the 1940s. By the 10th issue, the book was moving away from Beck, who was having what the volume at hand calls “creative differences over the direction of the book.”

Captain Marvel stories, almost from the beginning, were nearly tongue-in-cheek tales: they didn’t make fun of “the world’s mightiest mortal” (as Cap was called), but a thread of gentle humor was evident. The writers of the new incarnation, first O’Neil then Elliot S. Maggin, didn’t quite capture the essence of the character, Beck thought. He thought their stories were just silly.

Moreover, management was unhappy with Beck’s simple line drawings: they wanted a more muscular-looking Cap, and Beck, as I said, had been systematically ridiculing the bulgey-muscle superheroes of the day, so he was scarcely likely to draw Captain Marvel to these new imagined specifications. After doing one story in No.10, Beck went back into retirement but continued a presence in comics fandom as the “Crusty Curmudgeon” railing against bulgey-muscled superheroes and other sins he saw being committed daily. And he did that until he died November 23, 1989 at the age of 79.

Shazam No.8, the only issue of the first 10 that didn’t have a new Beck story, was a “Super Spectacular” issue, all reprints of some landmark tales, all of which are included in Vol.1. Among them, the origin of Mary Marvel and stories about Captain Marvel, Jr., Uncle Marvel, and the “lieutenant Marvels,” a trio of characters whose individual distinction was different hair color (and one was fat); Black Adam, the evil version of Captain Marvel, and Tawky Tawny, the voluble anthropomorphic tiger. Doctor Sivana, the evil genius whose plans to conquer the world are frustrated regularly by “the Big Red Cheese” (as Sivana calls Captain Marvel), shows up often.

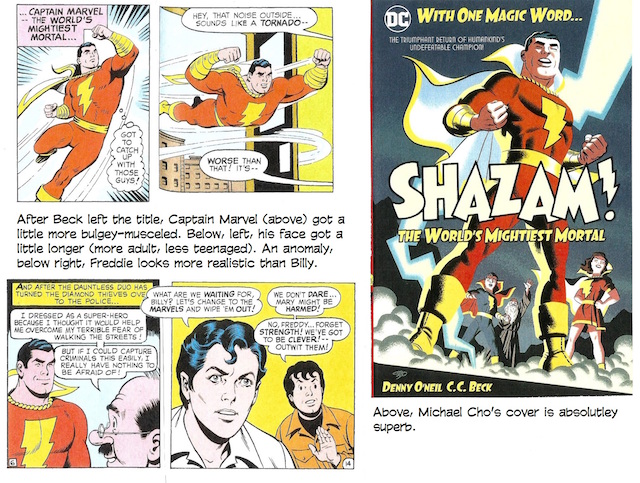

Bob Oksner did most of the art from No.11 to No.14, when Kurt Schaffenberger came aboard. In No.13, Captain Marvel starts to get some bulgey arm muscles, and the Beck-inspired visual starts to disappear. Cap’s face gets longer, leaner, less round under Oksner, and Schaffenberger continues that evolution. The book reprints only the new stories in Nos.11 through 18, and some issues had only one new story; they filled out the page count with classic reprints, which are not included in this book.

Three text pieces trace the history of the Marvel enterprise and introduce the cast. This is Volume 1, and it takes the Shazam title through No.18; Volume 2 will, presumably, carry on, perhaps to the last issue, No.35. But if Beck is present in those issues, it’ll be in reprints; he did no more work on DC’s Captain Marvel.

In supplying the cover for this volume, Michael Cho deviated spectacularly from the Beck model. But I don’t mind: his interpretation partakes of the Beck tradition, injecting just a glint of humor in the visual bravado.