The fifteen cartoonists assembled in the lovely and lavish Screwball! The Cartoonists Who Made the Funnies Funny, published by IDW Publishing's Library of American Comics, represent peak moments of laughter during some of our country’s most troubled times, from the Gilded Age to the Atomic Age. Combining more than six hundred rare cartoons, comics and photographs with deeply researched and insightful text, comics historian Paul C. Tumey builds the case for the genre of Screwballism, convincingly illustrating why names like Frederick Burr Opper or Boody Rogers should be at least as familiar to Americans as Charlie Chaplin or Mel Brooks. Better yet, he curates examples of the cartoonists’ work — much of which is previously unpublished since first appearing in newspapers — that make the case for themselves. Tumey — whose previous work on comics history include contributions to books on Rube Goldberg, E. C. Segar and Harry Tuthill, and an Eisner Award nomination for co-editing Foolish Questions and Other Odd Observations — brings to this book seven years of research and a lifetime of comics scholarship and fandom.

For this interview, Tumey and I spent two days typing at each other over Google Chat, while Tumey listened to old screwball-accented music. The wide range of topics reveals how pervasive a screwball sensibility can be, just as Screwball! The Cartoonists Who Made the Funnies Funny shows how great humor can be timeless.

Michael Tisserand: I’m going to start with the most personal question I can ask another person: What makes you laugh?

Michael Tisserand: I’m going to start with the most personal question I can ask another person: What makes you laugh?

Paul Tumey: The other morning, I came across an old New Yorker cartoon by Peter Arno that I laughed hard at. It shows a movie set where a vast World War One battle scene is all set to go, in what is obviously an indoor set. You see the trenches and dozens of costumed actors. We see the director and crew and camera. And there's a little tiny bird sitting on a barren tree branch. The caption reads: "Well we can't start until we get that robin out of there."

I laughed out loud when I read it. I think what gets me about this cartoon, and what makes me laugh is when life or art reveals the underlying absurdity of … well, everything. In that cartoon, the ridiculously extreme contrast between the deeply serious drama of war and the tiny little bird cracks me up. But now I am explaining the joke, which is the opposite of funny.

I disagree. You're not explaining, you’re celebrating, which brings even more delight to the joke. That's one of the reasons I love your book, but we'll get there soon enough.

I can say I prefer humor that is kind, if that's possible. Instead of poking at an individual or a group, I like humor that jabs at universal truths. Laughing should lighten things up, cast light into the shadows. It's kind of the way a clown works — s/he makes themselves the butt of the joke, not the audience.

Many of my favorite old comedians accomplish that — making themselves the real butt of the jokes. Including Joan Rivers or Don Rickles or others that some found or find offensive. But they're engaged in this act of stripping away something — pretense, politeness, civilization, maybe what Milt Gross would call banana oil — to get to something essential and very funny about our little shared human project.

Yeah, Rickles had this insult style, but he was really making fun of himself, I always thought. He created this absurdly cranky, obnoxious clown character. Sort of like A.D. Condo's comic, The Outbursts of Everett True. I think, to make me laugh, I either need that kind of layered, truth-telling gag or something that is just plain silly. I love silliness, which has gone out of vogue.

Where did you find your best early laughter? The funny pages, TV, movies, a funny kid in the neighborhood?

I was born in 1962 and lived in Baton Rouge, Louisiana for my first eight years. Then I lived in Alexandria, Louisiana for my next ten years or so. Of course I loved the comics, especially the color Sunday funnies. But, truth to tell, they weren't that funny except for a few standouts, like Peanuts, which was my favorite.

I remember reading Our Boarding House as a kid, but of course it wasn't Gene Ahern's version, since he left that strip in 1936. I liked it anyway, though, because of the fussy blowhard character of Major Hoople. The strength of Ahern's original concept kept that strip going for decades after he left it! I also remember reading Smokey Stover, which I loved. But more than comics I loved funny TV and movies. I remember watching W.C. Fields movies with my mother and us both laughing so hard we were crying and literally rolling on the floor.

Schulz certainly found laughter in the shadows, to paraphrase your introduction to this book. And while you note he wasn't a "Screwballist," which is a word I'm going to try to use constantly now, the screwball cartoonists were among his influences. So we see a shocked Linus with his hair sticking straight up, or Charlie Brown doing a sort of spin in the air after missing the football.

There are screwball moments in Peanuts, to be sure, but they are more like accents to the humor, and not the main dish. I'm glad you are picking up on the word I've coined, "Screwballist." I figure if you can have “Surrealist,” and “Cubist,” you can have "Screwballist."

Getting back to your question, my mother loved Little Lulu comics. She bought them off the stands as a little girl in Ponchatoula, Louisiana. Fresh John Stanley stories, although no one knew who Stanley was at that time. She passed her love of Lulu on to me. I remember laying in bed between my mom and dad as a little tyke and all of us reading comics.

For me, in the newspaper, it was Peanuts. But the laughs I really remember were at a pizza place in Indiana that showed W.C. Fields and Laurel and Hardy movies. I ingested more than my share of 1970s sitcoms but the projections on that screen in that pizza place blew my mind. They were so antic. One thing I noticed in screwball comics that relate to those old movies is the sheer amount of physical activity. Even the comics I love today rarely have characters who burn off those kind of calories. Usually they stand or sit and say funny things.

Oh, was that pizza place called Shakey's?

Village Inn, in Evansville, Indiana.

We had Shakey’s, which showed the old silent comedies on a wall. I was so fascinated by these. As a comic-crazed kid, I had this idea of somehow freeze-framing Chaplin shorts and using them as models for drawing funny comics. I'm still fascinated by how these brilliant comedies work. They seem as fresh to me as a movie made this year. Another early influence for me came in the 1970s, when PBS began showing Laurel and Hardy shorts and an Ernie Kovacs series. This, plus discovering Marx Brothers movies, was my first real introduction to screwball humor.

We’re now talking about old movies and pizza parlors, but I don’t think it’s a tangent at all. Your book illustrates just how interwoven screwball comics were with other entertainments, from vaudeville into movies. It makes this book indispensable to anyone wanting to learn about American humor in the 20th century, just as much as a book like Kliph Nesteroff’s great The Comedians: Drunks, Thieves, Scoundrels and the History of American Comedy.

I'm glad you caught that. When I started writing Screwball! I had no idea what I'd find. That was the motivation to spend seven years researching and writing the book — to see what I could turn up. One theme that quickly emerged was the many, many connections between all the forms of popular entertainment in the late 1900s and first half of the 20th century, especially between movies and comics. The two forms were born around the same time and grew up together. And in the early days of both movies and comics, comedy was as revered and celebrated as drama and genre forms.

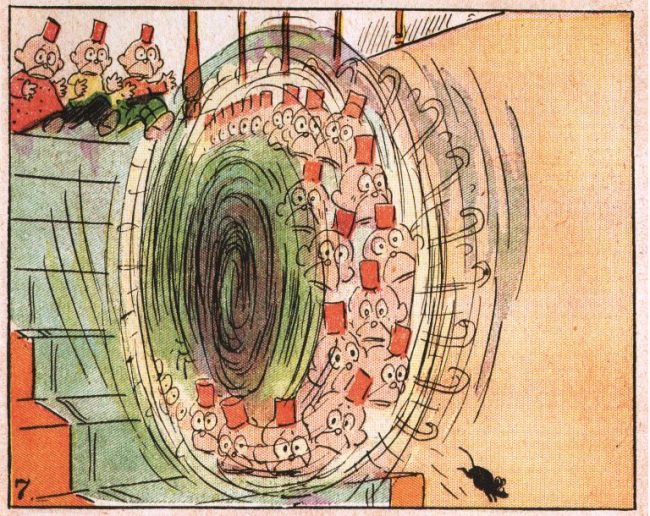

They were all drawing from vaudeville, but comics and film had to figure out how to use sequential visual narrative to make people laugh. You can really see this in Frederick Opper's panels of pinwheeling chaos where you have something like four heads, eight hands, twelve feet, and an alligator all swirling in a blur of frenzied action; it's like a freeze-frame of a movie! I don't think comics started moving like this until cartoonists started watching movies — that's my theory and I have yet to prove it.

Could you describe this affliction of being a comics-crazed kid?

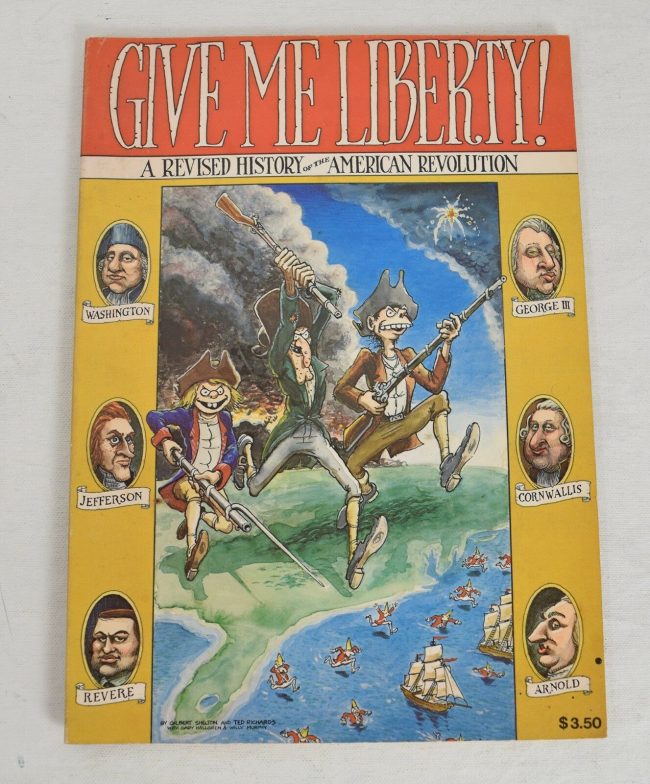

Growing up in Louisiana at a time when there were two TV channels and my family had little money, most of our fun was had fishing on and swimming in the lakes and rivers. I was bored a lot. Also, although I didn't know it at the time, I had a rather challenging upbringing since my parents were alcoholics. Comics lifted me up. One nice thing my parents did for me was to let me buy some comics through the mails, which was the only way to get something besides Marvel, D.C., Archie, and Dell reprint comics which were all you could find in the stores. I got hold of a Bud Plant catalog and bought some Crumb and Gilbert Shelton and man did that stuff make me laugh! Gilbert Shelton and Ted Richards created this wonderful screwball satire of American History during the 1976 Bicentennial called Give Me Liberty! A Revised History of the American Revolution, which I dearly loved. I used to laugh out loud reading it. It opened my mind up, providing a counter-narrative about the United States to the one somberly taught to me in school. Which gets back to that "truth-telling" aspect of screwball humor.

The other big event for me around comics was when MAD magazine reprinted the early Kurtzman material. They ran it as smaller color comic book inserts glued into the magazines. If you tried to pull the comic out, you wound up with a handful of torn paper! This was my first exposure to Will Elder, the funny side of Wally Wood, Jack Davis, and Basil Wolverton. I remember reading stories like "Ping Pong!" and "The Hound of the Basketballs" and spending hours looking at Elder's "chicken fat" background gags and giggling and guffawing. In some ways, my book is an answer to the question I've wondered for most of my life, which is, "Where the hell did MAD come from?" There's a note about this in the book's afterword, and also a nod to MAD in the title of the book, with the inclusion of the Kurtzman device of including an exclamation mark.

Right. We have now started at the end.

Which is appropriate for an interview about screwball humor!

Besides money and fame, is that the reason you wrote this book? To learn more about the history behind your childhood guffaws?

Oh no, it was just for fame and money! It kind of started when I was doing my blog on the great Screwballist Jack Cole. I wrote over 200 essays about Cole and his comics there and naturally wondered about his influences. At some point, newspapers.com got started up and I found Cole's hometown newspaper, the New Castle News, and was able to see what he read as a kid. His comic page had some of the great screwball cartoonists on it, including Rube Goldberg and Bill Holman. That led to the creation of a second blog about screwball comics. So I've been working backwards all along, you see.

At some point you decided that this thing you love needed to be better available so more people can discover these comics and fall in love with them, too. How long have you been considering this project and how long did you spend building it? And did you ever think along the way — like your story of Walter Bradford building a 30-foot wooden boat in an urban backyard without knowing how he was going to get it the hell out of there — that this whole thing might be folly? Did you have those nights?

I think the whole project took about seven years .Although I knew I would probably lose money on it, I never saw it as folly. Quite the opposite, it seemed like a very worthwhile endeavor. Nonetheless, it was a rough ride in some spots. However, I was all in from the start. I even gave up my seventeen years of self-employment to go back to a corporate job so I could have a simpler income situation which would allow me to focus more energy on this book, I would work all day at my corporate job as a graphic designer and then work into the early hours of the morning on my book. For years I worked like this, including most of my days off. I was as obsessed about this book as Wimpy is about hamburgers. But I will admit to having periods of doubt in my ability to pull it all off. What really got me through was that creating this book was a thrilling, addictive treasure hunt.

You see, when I started, many digital archives of newspapers and magazines became available online, as well as scans of comic books I had long dreamed of at places like the fabulous Digital Comic Museum. I became addicted to this pursuit. Sometimes, I'd be too excited by what I was finding to go to sleep. Discovering stuff like the story behind Happy Hooligan's tin can hat, or that incredible story about Bill Holman's father was truly exciting. Someone called this "research rapture." I imagine you know all about "research rapture."

Yes. It can zap you away, leaving only your shoes behind.

I have never stopped researching my guys and strips. More stuff becomes available all the time. Shortly after we went to press, I found a newspaper article in which Ving Fuller reveals the inspiration for Doc Syke was his experiences with the Army psychiatrists when he was drafted during World War Two.

Maybe we should get around to defining the term. You write that these comics were described as everything from “rubbernose” to “grotesque.” “Screwy” and “screwball” were adjectives used at the time, but not exclusively. How was it that "screwball" started to define a genre of comics?

The thing about the term "screwball" as I use it in the book is that I am kind of welding it onto comics history, retrofitting it after the fact. The book starts with this sentence: "They didn't call themselves screwball cartoonists." I want to be very up front about that.

With this book, I have to avoid defining the term "screwball" because I think we are still figuring out what it really is. I see it as a descriptor that can be applied to many things. I know cinema experts may have a difficult time with this book because they will see my use of the term as incorrect. I've already had some email exchanges with film scholars and, I'm happy to say, I've managed to win them all over to my way of seeing it, so far.

You don't define “screwball” in the sense of drawing a boundary around the term, instead choosing to amply describe it. Which makes this book, ultimately, your best answer to, “What is ‘screwball?’”

It’s not my best answer, but it's my best non-answer. And of course, at this point, I need to mention there is a great issue of Richard Marschall's Nemo magazine published in 1985 that collects screwball comics and has some of the same artists I've selected as well.

Yes, in the book you credit Rick with reclaiming the name for comics.

But I've wanted to be careful not to limit the scope of the form. That's why I've included an artist like Clare Victor "Dwig" Dwiggins in the book. His delicate, flowing line and beautiful women stand out in stark contrast to a lot of the comics of the time, but there is definitely Screwballism in his work up to about 1915.

So comics scholarship is sort of tugging on the tuxedo tail of film scholarship here, with its new definition of screwball. Most movies considered screwball comedies wouldn't make a good screwball comic strip. Bringing Up Baby, maybe.

Exactly! The way I see it is we are currently in the same place with comics studies in academia as we were with film studies in the’60s and ‘70s. If a film scholar can retroactively define a genre and give it a label, then I think comics scholars have the same leeway. What today we call "screwball comedies" in film seem to me could be much more appropriately labeled "screwball romantic comedies." You can have a "screwball" anything, even a western — look at Blazing Saddles.

Another look at “screwball” I really liked was the way Max Schulman described Milt Gross’s work: “You get the feeling that Mr. Gross wants you to laugh because he likes you.”

I think screwball is really playing with — in many different approaches — the absurdity which is part of the human condition. I mean, go to a Buddhist lecture, and you see the teacher and students laughing a lot. When you look closely at human behavior it's pretty damned funny.

As with that Ving Fuller story, there are overt nods to psychology and psychologists everywhere in screwball comics. And it seems if there is a single thread that runs through screwball comics — and there isn't but I've started this sentence so I’m going to finish it — it is sanity vs insanity, or steady vs punch-drunk, or logic vs everything else.

Yes, you are on to something, there. In a brilliant inversion, these so-called nutty cartoonists may actually be the sanest guys in the ball park.

And these comics span the development and popularization of psychology. This is civilization and its malcontents. These were mostly hard working, professional, responsible family men but they found a way to express — as you said it — silliness.

Well, it kind of seems to all start with Opper, a giant. He was indeed this sober, hard-working man from the Midwest. Most of his photos show this dude who looks pretty uptight. More like a businessman, as Winsor McCay noted, than a funny man. But Opper was the first great humor cartoonist in America. He did a ton of political cartoons in Puck magazine, where he spent roughly the first half of his career, but he also started this second stream of comics purely for humor. They had nothing to do with politics. Some of his Puck cartoons are quite silly. I show a few of them in the book. And Opper was indeed expressing his lack of contentment at the ways people and life in the United States struck him.

Wouldn't it be great to be able to watch Opper draw a screwball spin? With Maud, or a policeman, or Happy Hooligan popping up out of the maelstrom saying "help"?

I'd give anything to watch Opper draw a cartoon. I found an interview with him in a New Orleans paper in which a journalist describes watching him draw a cartoon on the spot. After he finished it, he turned it upside down and spotted the blacks and made final touches, which shows what an artist he was.

Your book reminds us constantly that these comics were in newspapers. So there were world wars and Depressions on the front pages, and times that seemed mad in a different way, just like today. Then you had this big release of laughter.

My theory is these screwball comics were a tonic for the people going through all these grim times. The crazier the world got, the funnier the comics got.

Madness is foundational in literature of course, in Shakespeare and Cervantes and before that, it’s shot through our religious texts and myths. But even in my lifetime we have a very different way of talking about it. When I was a kid forty years ago, we'd think nothing about joking about a place called the "Fergus Falls Funny Farm.” Not anymore. In the comics in your book, there is no shortage of jokes about looney bins and the like. How would you advise readers of historic screwball comics to be able to find laughter in these works, even when the content is now cast in very different light?

I would tell readers — and I hope it comes through in the text I wrote — these cartoonists were some of the kindest, most gentle souls you could find. They were not making fun of people with mental or physical disabilities. Quite the reverse, they were making fun of people who think they are somehow superior in some way. Screwballists love to poke holes in pretensions. In my research, I discovered Rube Goldberg had a summer job where he picked up people and drove them to homes for people who had mental illness. Goldberg was literally a man in the white coat. I think this exposure to madness made a huge impact on him, because the main theme in his work is how we are all mad in some way, and usually don't know it. Look at Opper’s treatment of Happy Hooligan. He doesn’t cast him in anything but a positive light. Happy means no one harm, but in his earnest efforts to help others, he leaves behind him a vast swath of chaos.

I knew that Herriman had built many of his characters on obsessive behavior, such as Major Ozone and of course Ignatz. I hadn't fully appreciated how much the humor in early newspaper comics rose out of such obsessions.

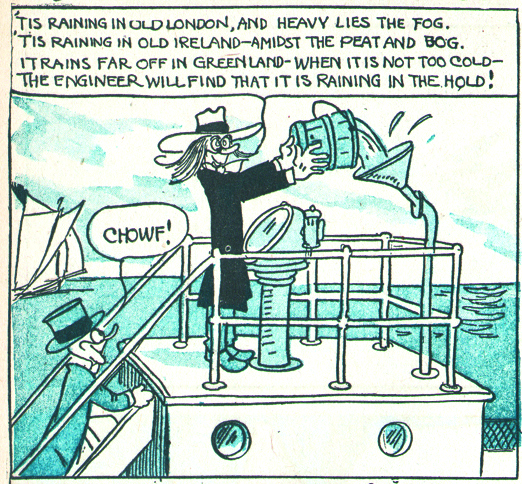

For a while, in the first decade of the 20th century, many comic strips were built around an eccentric behavior. W. R. Bradford had strips like The Almost Family, whose members could never be on time for anything, no matter how hard they tried. Or Mrs. Rummage the Bargain Fiend, about a woman who cannot resist buying junk to make herself happy. Winsor McCay had Hungry Henrietta, a highly sympathetic strip about a little girl's eating disorder. The Screwballists in comics at this time took these characters to extremes. W.R. Bradford's Jingling Johnson is about a poet who compulsively spouts nothing but bad verse. And to your point about sympathetic humor, Bradford drew himself as Jingling Johnson!

In looking at your fifteen Screwballists, some readers are going to ask, "Where are the women?" There weren't many female cartoonists in the first half of the twentieth century, but there were some. Did you consider any for this book?

I wanted to include cartoonists who didn't just dip their toes into the form, as many have, but the ones who lived and breathed it throughout large portions of, or all of their careers In the era I wrote about that seems to be the province of men as far as newspaper screwball comics goes.

So the limitation is historical then? Few women were employed as cartoonists so the options to include them were just that much more narrow?

Yes, exactly. There is a paucity of women cartoonists in the early 20th century to begin with. And among those, the ones identified as career Screwballists is — well, I couldn't find any. Which isn't to say there weren't any — I'm sure there were. Probably in local papers.

So Grace Drayton or Fay King or Nell Brinkley rubbed shoulders with the Screwballists but that wasn't what they set out to do. Histories of women in cartooning by writers like Trina Robbins and Martha Kennedy give an idea why.

I thought about including Kate Carew, but I honestly couldn't tell from the few comic strips she did if she had the screwball sensibility.

I've found that it's also true that in researching early cartoonists, their marriages are often the least understood aspect of their lives. There were no surviving letters between George Herriman and his wife Mabel, and most of what I could determine about their marriage and how it affected his comics was guesswork at best. Did you find any examples of women being significant contributors to these cartoonists' work, as wives or friends, or as editors?

No, I didn't find any information about the wives providing any significant contributions to the work, beyond keeping a home for the men. Again, that doesn't mean it didn't happen. We just don't know, with the materials that have so far been found.

One story I couldn’t include in Krazy was that Hearst would communicate with Jimmy Swinnerton’s wife, Gretchen, to make suggestions about Swinnerton’s work. Gretchen wrote back to say that Swinnerton didn’t want her advice.

I did find a delightful story about Boody Rogers and his wife taking a road trip with cartoonist Frank Beck and his wife. Rogers was assisting Beck on his strip, Gas Buggies. The newspaper article said the wives "all help with suggestions on stories and sketches.”

I imagine one of the greatest challenges you faced was how to deal with the foundational role that is played by racial, ethnic and other stereotypes in early cartooning. You address this most directly in your chapter on Zim but you also return to the topic throughout your text. This book is at heart a celebration of screwball, and Screwballists, and Screwballism. How did you — and how do you — factor in that critical piece of history?

The widespread use of ethnic, gender and other stereotypes in the first decades of American comic strips is a challenging problem for a modern comics historian working with this material. I wanted to acknowledge the inherent lack of awareness around these issues, but I also didn't want to offend my readers with offensive material. So I did include some examples in the art choices, but only lightly so. I relied on my running text to address this aspect to the material, but it is far from a main point in the book. Still, I think it is a key part of some cartoonists’ work. A scholar estimated about one-third, I think, of Zim's cartoons are racist by today's standards. I think Zim had some awareness of this in 1905 when he penned his impressive full-page cartoon, "Our Comic Artist's Nightmare," in which all his stereotypes exact their revenge on the cartoonist — a depiction of a troubled conscience, perhaps.

That’s how I see that cartoon. It's an incredible admission, but not really a penitence. The cartoon perpetuates the stereotypes even at the moment they afflict the cartoonist.

I think stereotypes were part of the cartoonist deal back then. Maybe so today, as well. Look at Crumb's depictions of women, or the way certain cartoonists draw the Gen-Xers. At a certain basic level, cartooning IS stereotypes.

Historically, stereotypes of African Americans are grounded in minstrelsy so the caricatures are generally much more gross, to the point where they seem like they are drawn in a different style than the rest of the comic. Yet — and this is as difficult as conversations about culture can get, I think — each artist and each work deserves to be judged on a case-by-case basis.

Well put. I agree wholeheartedly. “Gross” comes from ”grotesque," which is a key word in looking at cartoons and comics from 1880 to about 1950.Many early screwball cartoonists were known as “grotesque cartoonists” at the time. It think it’s neat that grotesque art is part of Screwballism’s DNA and one of the greatest Screwballist was named Gross: Milt Gross. In the early days, cartoonists strove to create grotesque imagery. And not just for laughs. The famed Puck publisher and cartoonist Joseph Keppler's center-spread color lithograph cartoons often showed the heads of political figures stuck onto animal bodies — extremely weird! Grotesque is also still in play today. There's a whole group of up-and-coming modern cartoonists like Max Clotfelter who play with grotesque imagery and get vital, authentic results.

I want to tell you about an incredible personal experience I had today that made me think of your work in this book. I attended a memorial service for an 18-year-old-kid who died suddenly in a freakish, tragic skateboard accident. A lot of his friends who spoke were kids. Eighteen-year-olds. And many of the stories they told were hysterical. One friend told of meeting him in a Waffle House and he was so excited to see her but he had his mouth full of waffles. Another was about a bus ride back from a soccer game when there was no bathroom so he peed in a bottle in the back of the bus —and bus hit a bump, sending the pee everywhere. These stories communicated something essential about what bonded these kids. They were the stories they told at their greatest time of grief. And they were screwball stories through and through. As I sat there listening to them, the line from Stan Laurel that starts your book — about humor being a tonic for depression in both individuals and nations — came back to me. And I began to see yet another meaning in Krazy Kat’s "love letter written on a brick."

I am so sorry to hear about that young man’s death. Your story reminds me of the South, where we laugh a lot. I was raised in the deep South and my family always laughed when we all got together. Once I was fishing on False River with my Uncle Joe and Granny James. I was about 8. We drifted underneath a cypress tree with the branches and moss hanging over us. A sleeping snake lost his grip at that moment and fell into the boat. Granny took her cane pole and started hitting my uncle with it in a panic. "Joe! Git that damn snake out of the boat! Git it!" My uncle was saying "I will Granny if you'll stop hittin' me and give me a chance to!" When Granny James died about a year later, it was a huge loss to the family, since she was the matriarch of our clan. My uncle told that story at the funeral and everyone laughed hard and then seemed to feel a little better.

I’m laughing now. You had me with "Granny James."

They told a lot of funny stories about her fear of snakes. Another time we were driving around town and she saw a sign for a snack bar. She croaked "SNAKE BAR!" And we all cracked up. I guess my family bonded through laughter. And in that way, I think all us humans, even total strangers, can bond thorough shared laughter.

Given the tradition of this Southern humor in literature, I would expect to see more Southern Screwballists.

Boody Rogers comes from Texas. He’s the one great Southern Screwballist in the book.

So many of your Screwballists' lives were touched by tragedy. Some had their careers started by it. Train crashes, people falling to their death from a hotel window ...

Yeah boy. Whew, there were some dark stories I ran across. At first, I tried to gloss over them with the idea this book needed to be a fun book and this stuff seemed too heavy. And then I realized these dark events threw the humor into sharp relief, so I began to give this material proper treatment. When he was very young, Dwig all but witnessed a relative of his murdering the town sheriff. And he had to testify in court. I was fortunate enough to find that transcript and reprinted some of it — an extraordinary event, and also a chance to read the words an early cartoonist spoke as a child. And then I found later on Dwig and his wife Betsy had a baby around the time he started his amazing screwball comic, Home Wanted By a Baby. The baby dies a year later and you see Dwig's art thereafter is frozen in boyhood nostalgia. So finding these forgotten stories adds enormous context to the art.

Those Dwig stories were staggering and Home Wanted By a Baby is astounding. The scene of the child watching his father laugh at mayhem in the comics but then punishing the child for trying out his own mayhem ... and knowing that the kid was trying to please his father … that’s a novelist's work in eleven panels.

There are so many layers to that one Sunday page! If you read closely, you can see one of the strips the father is laughing at is Opper's Maud. So the strip becomes a statement about violence in comics — or perhaps a parody of it. Curiously, And Her Name Was Maud had ended years before Dwig created that page!

The cartoonists seemed to particularly love that one. When Herriman was interviewed by Boyden Sparkes decades later, he brought up Maud.

It’s sort of a pure screwball comic, with the wind-up and then the mule's explosive kick. It's very funny because you know what's coming. But Opper rings numerous variations on the simple premise, just as Herriman did with Krazy Kat.

There are some moments in the comics in this book where the brutality is kind of breathtaking. The scene by Dwig of a baby with his ear in a bear trap, and blood dripping. And that Thimble Theatre in which Wimpy butchers a cow.

I was talking about how gentle-spirited these cartoonists were and now we are talking about babies in bear traps! But I think including this harsh stuff shows the screwball cartoonists understood how their form of humor was a kind of whistling past the graveyard. That the laughter they dished up was to quell some of the awfulness in the world.

What do you see as the relationship between screwball and slapstick?

I see slapstick as one element of screwball, but not the whole thing. A recent interviewer kept substituting "slapstick" for "screwball." To me, that is like substituting "perspective" for "painting." A screwball cartoonist may use slapstick (and they often did), but there are many other elements included, such as: verbal and visual puns, background gags, delightfully weird characters, grotesque imagery, satires, and so on. All of these are in service of a certain sensibility.

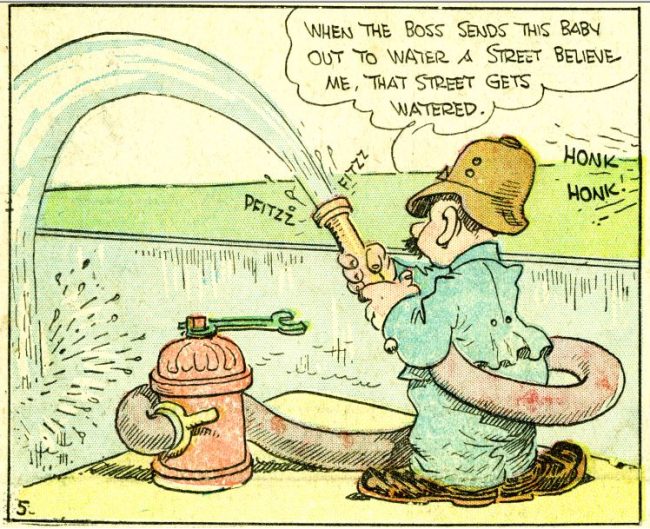

And the laughs come throughout the strips, not just saved for the punch. One of the happy surprises for me was how much I laughed out loud reading Walter Hoban. The set up in his Jerry on the Job where a fireman is watering the street is so delightful, because it's a little man musing to himself about the good job he's going to do watering the street, but a tiny "honk honk" in the panel tells you all you need to know about what's coming.

Absolutely! There's a warmth that comes through. I mean, these guys were making a living, sure — but they didn't have to go to such extremes to make people laugh. Where other humor cartoonists give you one gag per strip, a Screwballist works in multiple jokes. In one Dwig panel, I counted 37 jokes! Newspaper comics in the first decades of the 20th century were not meant to be read quickly. I think some of them were designed to be savored as much as the Sunday pot roast. Readers today, including me, are trained to zoom through a comic strip. By the time you decided whether or not to read Dilbert, you've already read it!

Actually, do you know why a man would be tasked with going out and watering a street?

Not really, and that's funny in itself. Whether it was a common thing back in 1922, when that Jerry on the Job Sunday page first appeared, I don't know. And that illustrates the Problem of Lost Context when it comes to writing about and presenting older comics. Sometimes you can't tell if something is a deliberate gag or simply funny because it is incongruous to a modern reader. That guy in the Jerry comic does remind me of old men who water their driveways. I used to have a neighbor who did that every day at 5 pm, like clockwork. By the way, as we talk, I am listening to Fats Waller’s novelty parody songs. He loved to lampoon hit songs. The music is so bouncy and boisterous I can't help but view it as Screwballistic.

Slim Gaillord gets pretty screwball, too. And Gaillord, like Herriman, had Afro-Cuban roots and spoke multiple languages.

Of course, there's Spike Jones. Milt Gross painted a backdrop for one of his touring shows. And Rube Goldberg even recorded a novelty song, "Father Was Right." I show his beautifully grotesque cartoon of making the record in the book. Milt Gross made three records in which he recites his Yiddish-English poems. I hope they surface someday.

What about radio shows? I've been thinking that Vic and Sade might get a nod for bringing screwball to radio.

The screwball cartoonists were all over the radio. There was definitely a stream of screwball humor in radio — probably culminating in Bob and Ray in the 1950s.

Their Wally Ballou could have been a comic strip star.

So Screwballism is not dependent on the form -- it is a sensibility. You see it in comics, radio, TV, and so on.

You chose fifteen cartoonists of that sensibility here. But you're not trying to create canon fodder here. You call them representative, but you're not setting them up as the greatest fifteen Screwballist masters?

Oh no, not at all. I think many of the cartoonists in the book rank among the greatest screwball cartoonists. But others may see it differently. For me, Herriman, Segar and Opper are at the top. However, I also wanted to offer readers some of my “finds” among the more obscure but worthy cartoonists. Plus, I think it’s useless to the reader to impose one’s own opinion about who is the best and who isn’t when it comes to art.

As I explain in the introduction, the original concept of the book included many more cartoonists. I realized I have to make a choice. We could either have a book with a lot of cartoonists and a little bit of text and art on each, or we could have a book with fewer chapters that go deeper. Since I was finding all this great new information and art, I wanted to go deeper. I have enough research and art to easily fill a second volume. One of the big limitations I imposed on the book early on was to only discuss American newspaper cartoonists. So the obvious candidates for screwball cartoonists like Basil Wolverton, Harvey Kurtzman, Al Jaffee, and Jack Cole were not included because they worked in comic books.

As a native of the Midwest, I have to say I was a bit astounded by how many of your Screwballists hail from that region.

I know! What is it about that region and silliness? I don't normally think of the Midwest as being the cradle of nonsense.

The hard-working ethos of the Midwest sort of underlies a lot of these characters. Like you said, Happy Hooligan just wants to help. And Jerry just wants to get his fucking job done.

A lot of these Midwest cartoonists migrated to New York to establish their careers. But once they had some success, they moved out of New York as soon as they could! Some moved to the other side of the country! A notable exception is Rube Goldberg, who kind of became the social mayor of New York.

Thanks to watching Peter Bogdanovich's documentary on Buster Keaton last week, I kept thinking of Jerry on the Job as a Buster Keaton figure, getting bounced on the head while maintaining that perfect blank expressiveness of the face.

I’ve had that insight, too. The straight-faced plops of Hoban are the comic strip equivalent of Keaton's film gags. Hoban uses the plasticity of the comic medium to do things Keaton couldn't, like having Jerry literally bouncing like a ball on his head with a dotted line describing his bounces. Jerry's body posture is no different than it is when he is standing still, which makes the whole thing much more hilarious than if Jerry was reacting to the pratfall. Hoban knew W.C. Fields, by the way. They were both Philly boys.

So who really makes you laugh again and again? When you need a shot of screwball, who do you turn to most frequently?

I’m so close to the material now, it's hard to single anybody out. I love all of the work included in this book. It all makes me laugh. That was a criteria for inclusion: It had to make me laugh, even if I didn't know why. But I guess if I was going to be marooned on a desert island, I'd want some Thimble Theatre with me. Because Segar managed to not just work with gags, but also long humorous continuities, which deepens the humor.

Has your own writing always been this funny, or do you credit your immersion with Screwballists? Because in reading the book, I laughed not only at the comics, but at your sentences such as "A bit of a character himself, Rube Goldberg swam with his shoes on." Your prose has plenty of its own gems.

I’ve always tried to inject humor into my writing, with varying degrees of disaster. You can see me getting pretty silly in my screwball blog but for an actual print book, I toned it down. I felt it important to try to match the tone and style of the other volumes in the Library of American Comics. Even so, like Bill Elder, I managed to work in a few gags around the edges. It was gratifying, in the edits stage, to get a "ho ho" in the margin from my editors Dean Mullaney and Bruce Canwell when they would spot one of my gags in the text.

Finally, who gives you hope for a healthy screwball sensibility in comics today?

I was afraid I'd get that question. I hate to mention certain cartoonists and leave out others. There are so many good and great humor comics coming out lately, it is really hard to get my arms around it. That being said, I can mention a couple. Tom Van Deusen seems to be almost entirely devoted to humor comics with some screwball moments. And I am just becoming aware of the work of Nick Maandag which seems extremely screwy and funny to me. I've ordered every one of Maandag's books and comics I can find.

To be honest, I'm not sure if we will ever see "pure" screwball humor again. I think this form was a product of its times. For a 21st century cartoonist to work in the screwball form is tantamount to modern painter working in Cubism, or a modern musician playing blues. You will find some "authentic" voices, but a lot of it seems to be people playing with the form instead this deep drive coming out.

I hope I'm proven wrong about this. We need all the laughs we can get these days!