THE PINNACLE

PINKHAM: You said that until Swamp Thing, you weren’t really known. Do you really feel that way?

VEITCH: Well, I was known, but I think Swamp Thing was the pinnacle of my being “known” — [laughs] probably throughout my whole career. That was the highest profile work I ever did. Especially after working for Epic magazine where I’d only be doing a page a week. People might enjoy those pages, but they don’t really remember who you are. Readers in America tend to be plugged into that 30-day mentality of, “We’ve got to have a new comic every 30 days!” That’s what they really remember, and everything else is just like side dressing.

Steve Bissette and John Totleben took over Swamp Thing at its artistic nadir. At the time, this seemed completely absurd. Steve and I were still really tight friends, but I had reached a point where I had sworn I was never going to work with him again because all of the deadline bullshit that had gone down. He was saying, “Well, I want to do a horror comic!” So he and John looked through all the comics published and there was only one horror comic, and that was Swamp Thing! So they went down and campaigned for the job — and got it. They were doing amazing art, but the scripts were your typical comic book fluff — there wasn’t much going on. I was positive the whole thing was going to crash. Then Steve called me up and said, “Yeah, guess who we got as a new writer? That guy from Warrior. Alan Moore.” He sent me over a copy of the first script, “The Anatomy Lesson.”

PINKHAM: I think that’s the best one.

VEITCH: It was as detailed as a non-nuclear proliferation treaty, but it worked. I was absolutely floored. And of course, Steve was going through his strange, freelance soap opera of on-again, off-again, “I can draw; I can’t draw.” And inexplicably disappearing for great lengths of time, putting the whole thing in jeopardy. I ended up become the uncredited ghost artist who assisted Steve, mostly just to get him going and back drawing again. He would just get himself into these weird moods where he couldn’t draw, and I would say, ‘To hell with it!” and drive over to his house and set up, and pick up the scripts and pick up the pages and start drawing and pretty soon he’d be rolling, too. I think I never asked for credit or payment because I didn’t want to accept that I was really working with him again [laughter]. Steve and John made sure I got credit and payment for the first collected edition, but DC was pissed off at me by the second collected book and they left me off.

But I absolutely loved every minute of it, too, because the scripts were kick-ass material and Bissette’s approach to the graphics was perfectly realized. It was an extremely strong book that virtually changed the direction of comics. Obviously, the reading public agreed. The book started taking off in a big way — I think at one point they were adding 5000 readers a month. Good sales. At the same time, we were beginning to get a taste of having to deal with a sick, old company like DC Comics that had all these arcane rules that were designed to keep freelancers working for dirt. Steve got caught up in tons of company bullshit which I think kind of colluded to keep him from working and concentrating on the book. He was feeling really bad about it a lot of the time.

PINKHAM: Any specifics?

VEITCH: There was one incident … I don’t think he’s even allowed to speak of it because he had to sign some crazy non-disclosure form — but I can talk about it. [Pinkham laughs.] He worked for DC for a year and they were giving him miserable wages, like $63 a page for this incredibly beautiful book that was making a name for them, and he’s trying to get the measly insurance policy from DC that DC supposedly allows all the freelancers to buy into. But they just keep putting it off, putting it off ... Then his kid got spinal meningitis and it was devastating. All of a sudden, there’s a humongous hospital bill and DC is disavowing all knowledge of it. It was just a huge mess. Finally, they settled and covered it but he had to sign some sort of form to never talk about it — your typical business move.

PINKHAM: It seemed like you guys — Totleben, Bissette, yourself — were passing the book back and forth between one another. Was there any point that DC started asserting their command over who was going to do the art?

VEITCH: Not really, because Karen Berger was the editor, and she’s got a really even hand at dealing with creatives. She was able to keep a pretty good balance. Steve was really flaky, I’ll say that. He created a lot of his own problems with all his publishers. But at the same time, DC I think threw some absurd stones at his ass — at all those guys’ asses — and the whole thing just got really bad, really ugly. At the same time, Alan was just taking off. It seemed like every week he’d have a new script down, and he got way ahead on Swamp Thing. Then he started doing the double-size issues, which made it more difficult for the art team. Each script was an incredible treat to read because of the density of thought that he brought to book. He would write the script almost like a letter to the artist, he’d talk about his life and what he’d read of your stuff, what he liked about the last story you’d done, and then he’d say: “Now I’m going to be absurdly obsessive about detail here, but draw whatever you want. I just tend to run off at the mouth. It’s really up to you what this story’s, going to look like.” Of course, I would try even harder to give him exactly what he was looking for. And there was usually something really worthwhile in each one of those scripts, there was always some kernel of originality and creativity that made it quite worthwhile to try to reach for what he was doing.

PINKHAM: It seemed to reach a peak at Watchmen.

VEITCH: Alan Moore created one of the great, mainstream, comic scripting styles — and it’s kind of simple. It’s not that tricky. But it tends to weave a story together quite elegantly. Mostly it’s based on irony. Almost every scene will end on an ironic note, although the irony is often seen from different directions. Every transition from one scene to another would resonate — whether it was a word or a phrase, visual, shape, something — so that the whole thing wove together into a kind of a tapestry. Beyond that, I think he brought a real humanity to many of his characters that was startling. In Swamp Thing, Abby becomes this complete person, right off the bat, in the first few issues, and it was ground breaking, his ability to do it. He was never that great with the villains. His villains tended to be kind of one-dimensional bullies.

PINKHAM: On American Gothic it seemed like he was pulling the villains out of the stock room.

VEITCH: The villains probably only seemed weak because everything else he did was so strong. The characters of Abby and Alex and the dynamic between them — you know that those characters are still living in my head? To this day, when I drive around in a car, sometimes in my mind I’ll create scenes with Abby and Alex [laughs]. And those were characterizations he laid down 10 years ago.

PINKHAM: If Moore owned it, you could call him up and ask if you could do another story!

VEITCH: Alan, and all of us, understand that we don’t have to own Swamp Thing. In fact we’ve talked about it: “Let’s do the Green Man.” — which would be the final Swamp Thing story that he planned and never did, which was the death of Abby. We’ll never get around to it because he’s lost his interest in superhero stuff. But we all learned, like in Watchmen, that you can create stand-ins for the old heroes and tell the stories you want to tell. And the audience will follow. It’s a neat little trick that I used in both Bratpack and Maximortal.

PINKHAM: Did you notice Alan as a writer getting manipulated by the editorial — not Berger as much but …

VEITCH: Only in the sense that they wanted to exploit him. In contrast to Steve, he really was a workhorse. He could just churn this stuff out like greased lighting — it was awesome. Whereas with Steve it was very difficult getting the pages out of him. So naturally the company tends to want to exploit the guy who will poop out endless pages of fresh, new, interesting material. You have to give them credit for allowing Watchmen to happen. I think the success of Dark Knight opened up a lot of possibilities in the minds of the people who run DC Comics. Especially with characters like Batman and Superman that had Ten Commandments engraved in stone about what you could and couldn’t do with them.

Miller had broken a lot of the “rules.” So Alan benefited from that. I did run into Dick Giordano a few years ago and we were talking about Watchmen. He told me something I had forgotten, which was that Watchmen was actually written as The Charlton Heroes, and then they asked Alan to change it. [Laughs.] Dick said he could kick himself ever since — because he was the editor of a lot of the old Charlton books, and here was his shot to bring them back big time. And he missed it. [Laughs.]

PINKHAM: So you’re gradually watching this happening and getting more and more involved, and finally you’re officially drawing it.

VEITCH: Yeah, it was strange how I got drawn in … I’m still not sure how it happened! [Laughs.] Most of it was I began to talk with Karen Berger a lot on the phone when she was looking for Steve [laughter].

PINKHAM: It sounds like a marriage going awry!

VEITCH: That was the kind of stage he was in at that time. He would concoct stories about pages that were done that weren’t actually done, and all that crazy stuff. So it became really obvious that they were going to need fill-in artists, and I had already worked on the book so … Boom — I was a fill-in artist. Then when Steve and John decided to pull out, I became the penciler. Right about that time Alan began Watchmen is when I became penciler. At the same time he’s doing Marvelman, plus he’s doing backup stories for half the comics on the stands — he was everywhere! He engraved himself in the comic readers’ minds.

PINKHAM: When Moore eventually left, they had to call in Gaiman and Morrison to mind those.

VEITCH: Well, DC was beginning to realize there was a lot of talent in England. And there was very little work in England at that point for that talent. The nature of the foreign exchange was they could pay them cheaply. So it was a good thing for everybody.

PINKHAM: They could keep the copyrights viable on these old characters.

VEITCH: You got it. What was amazing about Alan was, when I was penciling the book, he was usually phoning in eight pages at a time — we’d be that close to deadline. I’d be given 12 days to do the whole book. That was how tight everything was. But when I’d run out of script, I’d call him up, or Karen up, and the next day he would have written another full eight pages. You’d think that at that speed it would be complete shit, but it wasn’t. They were still really good scripts — some of those were great scripts. He did one called “My Blue Heaven,” which I think was my favorite. The story is that Swamp Thing has landed on this planet in Outer Space and populated it with vegetable beings based on all the characters in the book. And at some point at the end of the book, he realizes that the Abby construct isn’t really Abby.

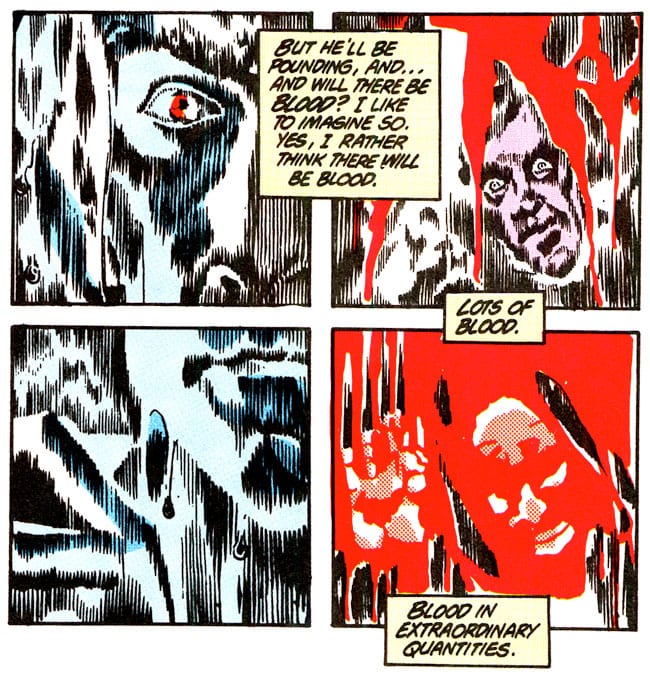

And in the script, Alan asked me to have Swamp Thing rip her head off with horrifying realism, and I tried to draw it, and I tried to draw it, but I couldn’t do it. I absolutely couldn’t do it. What I finally did was, I had him knocking her head off, but I had a big grin on her face to make it really obvious that it wasn’t a real woman getting her head ripped off, and that sort of worked. It was the one time that he actually took it farther than I could handle [laughs].

PINKHAM: I guess his fight with DC over Watchmen happened after you were writing Swamp Thing, right?

VEITCH: Yeah, I don’t think the battle was as much about Watchmen as it was about the standards that Jenette tried to impose on all DC comics. Out of the blue, she came up with a list of standards of things that couldn’t be done anymore. I suspect that Alan had been working for three or four years, and there was probably bad feelings festering and it all focused on the standards. So he resigned, and very publicly. That was the issue that he chose to go out on, and he made a big stink about it.

PINKHAM: Miller did around that time too.

VEITCH: A whole bunch went out together: Chaykin, Simonson. But I wasn’t included in that group, so I didn’t have to make the moral choice — although I probably would have joined them just for solidarity.

PINKHAM: Oh I see, so you really didn’t have any choice.

VEITCH: Right. I heard about it from Bissette, and I agreed with a lot of their points, but not all of them. So when the petition went around they didn’t send it to me. Too bad, because Jenette’s standards came back to haunt me a couple of years later.

PINKHAM: So this happened just after you started writing it?

VEITCH: Right.

PINKHAM: What made you decide that you could handle both?

VEITCH: Well, more than anything it was if I didn’t write it, I wouldn’t have stayed on as penciler. I really did feel close to the characters. And it was obvious to Alan and Karen and myself that there really was no one else to do it.

I think there was a certain amount of career death wish on my part. But, I understood the style he had created. I understood the synergy between the characters. I definitely wasn’t the writer Alan was, but I think I did a pretty good Swamp Thing. Some of the issues aren’t that great, but I was overall pretty happy with the results. I’d have to say that working with Karen really enabled to get the most out of what I had.

PINKHAM: She gave you advice?

VEITCH: She basically kept me safe [laughter]. And protected me from the corporate unconscious of DC Comics.

She also gave me, and this is something that no editor had ever done before or after, she gave me the option to do a final edit after the whole book came in to her desk. She would send me a set of Xeroxes of the whole thing, she and I would get on the phone. Any words or sentence structures that didn’t quite work, didn’t quite make sense, she and I would go over it and come up with a solution. And we saved a lot of scenes that wouldn’t have worked. She really did go that extra step. I got to give her credit. Something really strange happened at that point: I think I was into my second issue and hadn’t been paid for my first. I’d written and penciled the first issue, was writing the second issue, and I’m broke. I haven’t gotten the check. “Where is the check?” “Urn, I’m not sure. There’s seems to be a problem.” I said “What problem?” [Laughter.]

As it turns out, DC Comics has a policy that if you write and draw the comics, then work-for-hire doesn’t apply. So they gave me a choice: either I become a corporation, or become an employee of Warner Communications, neither of which I wanted anything to do with.

So it was like this big, stressful shitfight that we had at the beginning… with me finally acquiescing, saying “OK, I’ll become an employee of DC Comics, as long as I can have some sort of clause saying that I can do other comics for other companies.” I was not locked in completely; this was just for Swamp Thing. We worked out the wording, and all that kind of stuff. We did all that, and then they didn’t want to give me any of the benefits [laughter]. I began to really see, in stark terms, how freelancers were screwed. I had to fight to get the same insurance, retirement and vacation package they give the guy in the mailroom.

The worst part is the freelancers, under work-for-hire terms, look like an employee; act like an employee; smell like an employee; but they don’t get any of the benefits of an employee.

Fortunately, at this point, I met Eastman and Laird, in Massachusetts, and they had just had a black-and-white hit in the Direct Market with the Turtles.

Peter was my age, Kevin was in his early 20s at that point. They put the comic out ... They kept ownership, even though they had made the rounds and tried to sell it to Marvel and DC. They had been turned down everywhere. They ended up self-publishing the damn thing. And they had great success. They had linked up with Dave Sim. This was the point in which I’m beginning to get into Sim’s orbit, and he had been meeting up with Eastman and Laird at conventions and they were all talking about how to get people into self-publishing, and try to define why self-publishing works, and what parts don’t work.

Dave came to a comic-book symposium that was going on at Greenfield College, in Massachusetts, where I first met him. We did a panel, and he instantly raked me over the coals as a DC stooge. You know, he was feeling his oats, he had a couple of drinks; we’re all standing around, and he’s telling us these hilarious stories about being with Colleen Doran at a convention, and all these middle-age artists, you know, from the generation ahead of us, are coming around and acting like complete male chauvinist pigs to Colleen and Sim was doing these outrageous imitations of these people we all knew. And unfortunately, at that point my wife walked up. He had never met my wife, and I introduced him, and he went right on with his imitation of a middle-aged artist chauvinist pig, aiming it all at her! It was a strange way to meet the guy [laughter].

PINKHAM: Don’t show her Cerebus #186.

VEITCH: I guess because of the dynamics of our situation at that point, he would paint me as an apologist for DC Comics, which really wasn’t where my head was at. He had just begun to release his phone books, and he had cut the distributors out. And this had caused great consternation, I think with Diamond.

PINKHAM: They pulled Puma Blues.

VEITCH: That’s right. They whacked Sim by refusing to carry Puma Blues. And we began what we called the “Blacklist Group.” It began as these really informal meetings between Eastman and Laird, and Bissette, and myself, and Steve Murphy and Michael Zulli, and whoever else happened to be in our local Massachusetts, Vermont, New Hampshire area.

And we would just sort of go to a diner and eat greasy french fries and talk about what was wrong with comics, what was wrong with work-for-hire, what was right in self-publishing, and I was beginning to think more about “Yeah, yeah, this self-publishing thing can work.” And this sort of all evolved into the “summit meetings,” which I think began with the Kitchener meeting sponsored by Sim. And the second summit meeting in Northampton was sponsored by the Turtle guys. And they brought in Scott McCloud, Larry Marder, and myself, Sim, Gerhard …

PINKHAM: They provided transportation?

VEITCH: Some people I think they helped. I think Mark Martin was there, Richard Pini, a bunch of the guys at the Mirage Studios, which was really starting to grow. Mirage had just signed with Surge.

PINKHAM: Sounds like they were putting their money where their mouth is.

VEITCH: Well, you’ll see as I tell the story that it became a real point of contention. As soon as we got there, Scott McCloud produced a rough draft of what he called the “Creator Bill of Rights.” We started debating it the first day, trying to define what the inherent rights are of a person who creates a property in the comic-book field.

And we said, “Yeah, this is a worthy thing for us to do.” We spent a couple of days trying, word for word, to define that a person who creates something owns it before he signs it away. It sounds slightly absurd, but believe me, a lot of those things were not defined in those days, especially by the big companies. A lot of rights were assumed by the big companies without so much as an eye blink. And we felt it was a worthy cause to figure it out and to try and get everything down on paper. It was much more difficult than it sounds, to get the correct wording, and I think we all agreed on the final document, although certain people objected to certain clauses in the document.

PINKHAM: Did you have any?

VEITCH: No, I was happy with the whole thing. And I learned a lot hashing it out with these guys. At the same time, of course, Sim and Eastman and Laird are beginning to work on me to self-publish. They got their eyes open for people who know how to write and to draw and to letter. And they were trying to convince me to learn the next level of skills, which is self-publishing. And I was kind of dragging my feet, I’m having my problems with DC but in my head I’m still thinking that the best thing for comics would be for DC to change their policies and act decently towards freelancers, not for DC to be torn down. Which was basically what, I think, Dave and the others felt at that point. That these structures should be destroyed, not rehabbed.

But, at the same time, we had a lot of common ground. I feel this with Dave especially. Creatively, I really click with him. We start to talk about cartooning, and the nature of creativity, and the energy levels really start to rise. Non-verbally, I think, we have a connection through the nature of comics and how they’re created and what it means to do that kind of work. The interesting thing that happened at the end …We signed the document, and we’ve taken the picture, and we have one last meeting. At this point, Dave very pointedly began to criticize Eastman and Laird and Mirage Studios. And he, I can’t remember his exact wording, but he saw a studio set-up that they were building which involved bringing in a lot of young artists from all over the country to Northampton and hiring them to do Turtle comics and merchandising.

Dave saw this as a dead-end road. He laid it all out. He thought they were getting away from being self-publishers. And it got really intense, and Eastman and Laird took it very personal, and didn’t want to hear it.

The meeting kind of broke up on that sour note. And I don’t think Pete and Sim ever really connected with each other again. But I think they should have listened to what Dave had to say at that point. A lot of things he predicted came true in spades later on down the road.

PINKHAM: It seemed like Eastman started distancing himself from Mirage at that point.

VEITCH: That’s when he formed Tundra. Actually, at the point I’m talking about now, Eastman and Laird were a smooth functioning partnership. They were completely contrasting personalities. Kevin is ebullient and charismatic and all energy, he’s all happy, he’s all fun; and whatever you say to him, he goes, “Yeah, let’s do it.” Peter is more laid back and cynical. A better businessman. He won’t jump into things. He’ll think things out, and find a real good reason for doing things. The two of them made a lot of really smart decisions, consciously or unconsciously, before everything got out of hand.

CRUCIFY HIM!

PINKHAM: It seemed like there were little things that plagued you when you were working on Swamp Thing: changes in format, cross-overs…

VEITCH: Those are the kinds of things that take the wind out of your creative sails when you’re working on a book. It’s the guys who run the business side of it; they don’t have a clue about what they’re doing to their creative people. They sort of offhandedly toss these bogus decisions into the creative people’s laps... I think the people that really survive the longest in the pressure-cooker of companies like DC and Marvel are the ones who can just adjust to whatever gets thrown at them, and I wasn’t that good at it.

PINKHAM: You said in your King Hell press release that DC couldn’t handle your superhero limits.

VEITCH: If you look back at my run on Swamp Thing, there’s a page of Superman’s chest symbol and you look at the lettering style in the captions. And there are two or three captions that were re-lettered. And that’s because what I wrote in the first three or four captions was too much; it set off the alarm bells in the DC hierarchy —

PINKHAM: What did it say?

VEITCH: Well, it was me talking about the dark side of superpower. And I’m beginning to formulate these ideas for The Bratpack, right? And, they went, “Well, hey, talk about heroism and good deeds and that kind of stuff.” I ended up having to write two or three sugary descriptions to add to the bits I had done.

PINKHAM: So where did that come from? At that stage it was even going up to the higher-ups?

VEITCH: I’m not sure who ordered that. It could have been Karen who flagged it. You have to understand that superheroes are their business. Anything that stains it they tend to freak out a little bit.

PINKHAM: I thought it was interesting that you chose the “Invasion” crossover, which could have been a real intrusive element, as the start of the time travel thing.

VEITCH: I wanted to get out of it any way I could [laughter]. Those were the things that you dreaded. They would go out on some retreat, come back, and have some cockamamie crossover and you had to work it into your comic.

PINKHAM: When you decided you were going to do the time travel stories, did you see the potential controversy that might come when you reached crucifixion?

VEITCH: Slightly. What I did was I proposed the story to Karen. She told Dick Giordano what I had in mind. And he wanted to see an outline. It got accepted. He wanted to see the script as it came in. I think I did it in two parts. And it was accepted. I guess at that point Jenette wasn’t part of that loop, and I don’t know why it wasn’t until that whole issue was done that the flags started to come up.

I think everybody was taken back and surprised by Jenette’s reaction to the issue. I don’t think Karen agreed with her thinking. I don’t think I’ve ever met anyone who agreed with Jenette, that the issue shouldn’t be published, or the idea shouldn’t be written about.

But you know, we all tried to solve the problem. We remain pretty good friends. We didn’t get mad at each other. Although at the time, I think I did write a couple of letters to express some anger.

So I quit. The whole thing kind of went away. It was no big deal. Then MTV picked it up. Then Wall Street Journal picked it up. And then Time picked it up. And then all of the sudden it was like everywhere; I was talking to people all over the country: radio interviews, it was a blast. And it taught me a lot of why stories become stories. Why does a certain fluffy item like Swamp Thing #88 become a story that is followed by the print media? You have to get inside there and watch it happen to understand the dynamics.

PINKHAM: The Wall Street Journal one was kind of flippant.

VEITCH: Yeah. It was very flippant, but I think it was like a direct hit on the DC bunker. Remember, the Batman movie is about to be released. Time and Warner are attempting to merge. The religious right is all over the media, and Salmon Rushdie has been condemned to death. That issue was dedicated to Salmon.

One of the funny things that happened was that lady from Time called to interview me. She told me Time was running the story because all the employees at Time were losing a fortune on their stock options the way the Time-Warner merger was happening, and they were pissed off at Warner [laughing], and they were running this story, and probably a lot of other stories to make Warner look like shit [laughter].

PINKHAM: I had never heard that angle on it.

VEITCH: It’s a very real angle.

So I was feeling great, but they got me good before it was over. My wife was pregnant, the baby was due; it was just a couple days before she went into labor and we got a call saying that DC was going to fire me as an employee of Warner Communications and they were canceling my health insurance policy. Anyone who’s had a baby knows the last few days of labor watch are just incredibly tense and you’re extremely vulnerable. I was devastated. I got right on the horn to the Warner personnel department, and it turns out there’s a law against canceling health insurance for retribution because I was a real employee, not a work-for-hire! I was able to keep it up by making the payments myself. Fortunately, all went well with the birth, and we got this great little baby boy named Kirby. It seemed so fitting, after all the bullshit that Jack Kirby had been through, and all the bullshit I had been through. It seemed a perfect exclamation point.

THE HUMAN COST

PINKHAM: Then you were looking for new things to do.

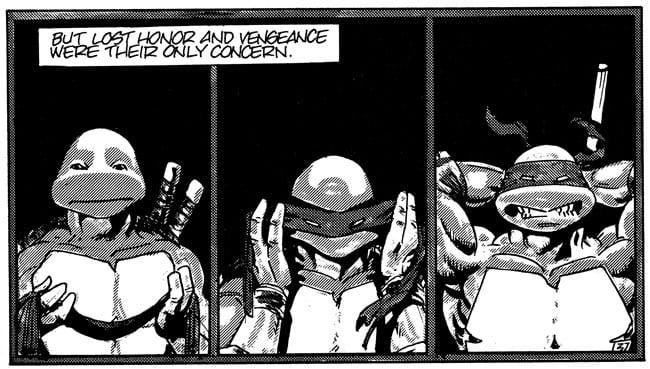

VEITCH: After Swamp Thing #88 had happened, Peter Laird called me up, and said, “Hey, why don’t you do a Turtle book?” So I said, yeah.

I didn’t quite understand the Turtles at first. I hadn’t really read the comic. I knew the guys, I flipped through their comic, but I hadn’t really sat down and read it. My other son, Ezra, was 12 at the time and I asked him, “What’s with these Turtles?” And he kind of looked at me. “It’s a joke, Dad. Don’t you get it?” [Laughter.] As I read them, I began to get what the Turtles were about, and why so many people were ga-ga over them. And settled down to start writing and drawing a three-issue miniseries.

I was paying the rent, hanging out with all the guys at the studio, stuff like that, and then the movie comes out. And the movie ignites one of the biggest pop culture fads in 25 years! And then all of the sudden my phone starts ringing off the hook from every real estate agent, stockbroker, car salesman, everybody I’d ever met that knew anything about money was calling me up because I was somehow connected with the Turtles. And they all wanted to meet my Turtle friends. I just basically shut everybody down. But I know what Kevin and Peter must have been going through at that point. I mean, when the movie hit, they were totally overexposed, on television, newspapers, everywhere, being touted as the success story of the early ’90s. The buzz was all about how much money they made and within weeks they were inundated with every kind of lowlife, rip-off, scumbag and legal beagle in all of New England, if not the whole country [laughter].

PINKHAM: The sweet smell of success.

VEITCH: It was more than anyone bargained for. And what was interesting is that it formed a kind of closure: comic books begin with Siegel and Shuster being tragically denied any share in the huge success of their character. With Eastman and Laird, you’ve got just the opposite. It’s like 50-60 years later that finally creators hung on to their characters and the magic hit again. But there’s a downside to that success.

PINKHAM: And then they were kind of shut off from their characters in a way as well.

VEITCH: I don’t know. They were pretty sly about setting it up. They separated the cartoon characters from the comic books. And they let everyone know: there were the little-kid characters in the cartoons; and then there were the real characters in the black-and-white books. They never tried to tone things down. But it was like trying to ride a cyclone. The tragedy of Mirage is the human cost of that kind of success; it’s just a horrible thing to witness.

PINKHAM: How did you start noticing it?

VEITCH: Well, right after the fad hit, Kevin and Peter became incredibly wealthy. That Christmas they went around and handed out big bonuses to all of us that really weren’t deserved. It seemed that that generosity brought out the worst in everyone. Pretty soon, there were lawyers everywhere [laughter]. You couldn’t turn around without bumping into a lawyer. And things began to get kind of strange; it was obvious Kevin and Peter were disagreeing with what to do next with Mirage. Which is why Kevin formed yet another company. Mirage always tended to be lightly organized. But once Turtlemania hit with the huge growth in personnel and lawyers and more lawyers and more lawyers, it just became impossible to get anything accomplished. That’s when Bissette and I got approached by Kevin about starting a new company. And he introduced us to his Uncle Quentin, who was the guy who lent Kevin and Peter the money to print the first Turtles book. Kevin’s idea was to start a company that would revolutionize how comic-book properties were brought to market. He wants to base the business on creators’ rights, and the Creators’ Bill of Rights. And he wasn’t worried about making a profit. The accountants had told him to invest his fortune or pay out in taxes and profit. Kevin really took that to heart. He started Tundra, and he bought into a number of other companies.

Steve and I and Kevin sort of worked out a plan for what we thought Tundra could be. Again, there was really no need to make a big profit. So Tundra could publish lots of esoteric titles, which there weren’t that many of in the marketplace. The original plan was to do five titles the first year and 10 the second year, and then cap it at 15. The first title we did was Bratpack, which I think at this point I was planning to completely self-publish as a black-and-white comic on my own. On a handshake, we worked out a co-publishing agreement that Bratpack would be published as a King Hell book, they would put up the money so I could do more intricate half-tones. His organization would take care of business and marketing things so that I could sit back and create; and we split the profits. This really pissed off Dave Sim, who saw Tundra as undercutting everything he was trying to do with getting people involved in self-publishing. I was one of his prime targets. He had been instrumental in helping me to self-publish The One trade paperback. At that point, that was the one project I had actually self-published.

PINKHAM: Before Tundra?

VEITCH: Before Tundra. And Sim had been instrumental in helping me get credit with the printer. That whole coming, together of self-publishers really began to unwind with Tundra. Now, it seemed, there was no reason to self-publish with Tundra around, because they would take care of the business problems and artists would be free to create. And I fell for it. And I was warned, by Sim in no uncertain terms, what would happen, what all companies tend to do. But I don’t think even Sim was ready for how fast things went screwy.

PINKHAM: He probably wasn’t used to a company that was being run by a very generous benefactor.

VEITCH: Kevin lost control of it very early on. That first summer in San Diego. He had bought into 65 projects. And everything became this mad dash to build an organization to handle that much material overnight.

PINKHAM: Was word going around that he was buying stuff?

VEITCH: I don’t think it was like that. Although word does travel quickly through a creative community when things are happening. Bissette and I were trying to keep a lid on it. We could see it already getting it out of hand. Originally, we had hopes of bringing in Alan, and Neil, Dave McKean, and few key people like that and turn out the first five books. Our idea of Tundra was to be able to concentrate things and make a big splash with a few really cool projects. But Kevin was just insatiable. It was his thing, his choice. No one talked him into it. But I think he tended to be a patron as well as a publisher. And he did, because he loves cartooning, and he had so much wealth he just wanted to help people. A lot of terrific creative people are barely getting by in our society. He bought a lot of artwork, and he didn’t like to buy single pages. He would buy a whole miniseries. And this could make a big difference in some poor artist’s life. Kevin was also planning his museum so it was a way of funneling more money into the community that would have gone to taxes.

I think in a big way Kevin changed the economics of what it is to be a comic-book artist!

PINKHAM: I remembered seeing Tantalizing Stories, and thinking that it was great that comics could finally support something like this.

VEITCH: More than once. I heard people say that the whole reason Tundra existed was to publish Frank in the River. And Understanding Comics. I don’t think there were any publishers out there at the time who could have done either of those projects. They got behind them in a big way. They got out there and found their audience. They’re both high-water marks in comics publishing.

PINKHAM: What was the situation like when you sold Bratpack? Did you get a big advance to live on?

VEITCH: No, foolishly I didn’t exploit that [laughter]. All I wanted was a decent page rate, so I got paid as I turned in pages. I didn’t want to get behind and not deliver. A lot of other people had a lot of other deals. But I came in at the beginning, and I saw myself as part of Tundra. I think Steve felt the same way. Especially the first year. As the company desperately began to grab any warm body and put them into positions of authority, Steve and I worked really hard to try and solve a lot of personality conflicts that arose. There were no real lines of authority. Kevin was way too vague about his goals, and underneath him there tended to be this mad free-for-all the entire time, about what Tundra was, what direction things were going in. It was a real mess. I don’t think we ever really got control of it. Until near the end, when he sold it to Kitchen.

PINKHAM: Wasn’t Bratpack supposed to also be published by Ballantine Books ?

VEITCH: Oh yeah, yeah. It was Dell. That was another great debacle [laughs].

Tundra got an agent, and the agent ran an auction, and out of the auction, they made a sale of, I think, five Tundra projects, and Bratpack was one of them. I think From Hell was another, and Melting Pot; I’m not sure what else.

PINKHAM: How does an auction work?

VEITCH: It’s done by fax. The fax goes to 20 different publishers, and you say: “You can buy all these titles. We need your best offer by ‘blah blah blah.’” Then they fax you their best offers. And we got a pretty good one for Bratpack, I think it was $50,000 to deliver film.

Of course, I’d just finished the comic- book series and all my friends had called me up. “Man, you blew the ending!” [Laughs.] So, I went back to it and reworked the whole novel: rewrote chunks of it, added pages, gave it a completely different ending with the help of Bissette and Neil Gaiman (who read the thing over, suggested things, and kind of acted as the de facto editor) [laughs]. And it came together — it actually worked — but that meant going back and redoing all of the film, which was a major expense and a headache for dear old Paul Jenkins in the production end.

But we did it, and I was down at Tundra the day the book was supposed to go to press. I was checking bluelines, and Kevin called me into his office. He had been called by Dell, who were pulling out because Waldenbooks refused to carry it because of a crack-smoking scene. And right in front of my eyes, the whole deal just completely unraveled.

It put the project deep in a financial hole. Bratpack had actually made money up to that point. It had paid back all its own costs, and was in the black (not by a lot, but being in the black was a strange thing at Tundra) [laughs]. And with all the extra film work, I think it’s still in the hole. It was a heartbreaker.

FEEDING THE HUNGER

PINKHAM: What were you trying to do with Bratpack?

VEITCH: It was a catharsis for me, because I had been on the track to becoming one of those workhorse superhero artists that fill pages for big companies. I’m someone who thrived in the pressure cooker of comics, someone with the mania — I think that’s the right word [laughs] — for superheroes and for drawing lots of comic-book pages.

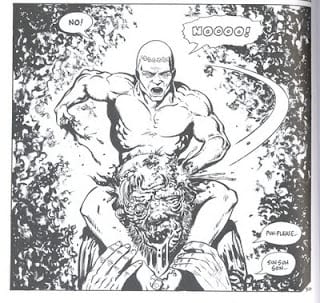

My experience at DC had soured me. After Swamp Thing #88, I wanted to tear the whole thing down. Bratpack was very much a scream of betrayal about my own personal feelings towards superheroes; how my childhood love of the form had been devoured by cynical businessmen.

I was frustrated after having spent three or four years working on a company’s stable of characters and held back from really trying to make important points about superheroes in general and certain characters specifically.

Bratpack for me was also a result of having a lot of problems digesting Reaganism. [laughs]. I guess a lot of people were. Vigilante archetypes were running rampant in the culture, pushed along by the needs of politicians. Fear, paranoia were the order of the day. We sent the army out to fight the war in the Gulf to lines taken from old Clint Eastwood movies.

PINKHAM: “Go ahead, make my day.”

VEITCH: But I was trying to make a point about vigilantism: how it had been grafted onto the modern superhero. I just figured I’d make the meanest, baddest, most outrageous superhero vigilantes that can be done, figuring that it would outrage people enough to stop reading superhero comics. In hindsight, I’d say that it didn’t work; it fed the same hunger in readers that feeds the superhero machine right now, and just brought it to another level.

PINKHAM: Did you get letters congratulating you in ways you didn’t intend?

VEITCH: I got letters from some creep in the Man/Boy Love Association congratulating me on the Midnight Mink and Chippy [laughs]. So, I’m proud of Bratpack, but at the same time, I wasn’t quite prepared for how some people could use it to rationalize child abuse.

PINKHAM: You just said you were trying to stop people reading superhero comics with Bratpack, but that was also the first book in your King Hell Heroica.

VEITCH: The thing is, I didn’t think it would really work. I didn’t actually think superheroes were about to self-destruct. Then I started Maximortal, and the death of Superman happened — which I tend to see as a major historical juncture in American superheroics. I suspect the death of the superhero archetype might have been signaled to the body politic by this cynical corporate play for more market share [laughs]. Sure, they brought him back, but everybody out in the real world thinks Superman’s dead.

PINKHAM: That said, do you stick by your original description of the Heroica as a ten year project?

VEITCH: Well, it will take another seven years of work to finish it, and I know now’s just not the right time. In pure business terms, to attempt a color superhero comic by myself would create a very difficult economic problem for me to solve. And in terms of what I’m trying to say about superheroes, the whole process is working itself out in the larger context of the culture. The things I felt weren’t being said are now being said, and the superhero phenomenon may now be heading for a transformation. I think it’s best for me right now to sit back and see what transpires.

PINKHAM: We should return to Bratpack, to clear something up. You reworked the whole series, particularly the last issue. Did your friends’ response change what you were saying with the book — not just the way in which you said it?

VEITCH: The first version, like I say, was a weird catharsis and I didn’t plan it as well as I should — going back to what we talked about earlier with Heartburst, where it was more about what I was feeling, rather than something I was thinking out. That kind of happened with Bratpack. Part of the reason for that, though, is the general madness of trying to help set up Tundra. While I was doing Bratpack I was also serving as, without an official title, part of a braintrust trying to get Tundra up and running, organized and on track with creators’ rights. A lot of my time was being spent solving personnel problems, trying to show people who had never worked in comics before how to do basic publishing functions …

PINKHAM: So you were taking a lot of trips down to Northampton?

VEITCH: Oh, yeah. Between Bratpack and trying to help Tundra plan, I was probably down there once or twice a week that first year — we were trying to set up contracts, all this crazy stuff anyone starting up a big publishing company has to go through. That’s one of the reasons I can’t complain about what happened, I was right in there, working on it, and had a lot of say, especially with my own projects.

PINKHAM: Did any of the “official” employees resent your involvement when you were trying to teach them how to publish?

VEITCH: Well, I wouldn’t say I was trying to teach them how to publish; it’s more like I would be there, so when troubles cropped up I was there to offer possible solutions, not “create” solutions. I had no power over anyone, other than the fact that Kevin seemed to listen to what I had to say.

There was sort of a power vacuum, because Kevin was very vague about what he wanted, and if two people had two different ideas about what Kevin wanted, things would get really confused and out of hand. I just think it was lack of experience in the personnel that caused a lot of the problems.

PINKHAM: A major part of Maximortal is the screwing of comics creators by their publishers.

VEITCH: Maximortal is a fictionalized take on the Siegel and Shuster story which has essentially been shut down — co-opted by Warner.

PINKHAM: That’s a pretty big force to be up against.

VEITCH: Yeah. I think Siegel and Shuster themselves finally gave into it because they had to be taken care of. When the Superman movie came out, they were old men, and Warner was kind of shamed into giving them an annual stipend by the creative community. I guess they didn’t want to rehash the sad history of Siegel and Shuster in the press. So they gave them a stipend, a tiny fraction compared to what Superman’s generated over the years. At that point, they clammed up. There is speculation they had to sign non-disclosure statements to get the money.

PINKHAM: It seems to be a favorite corporate strategy.

VEITCH: Just before the movie, Siegel gave a number of interviews, in which he discussed a lot of the things that had happened — I was able to find some of those interviews, although they’re pretty hard to track down — and I came away from reading all that stuff thinking that yes, it was a real tragedy.

I wish someone would actually research and write a true history of Siegel and Shuster and the character they created. It’s as if Conan Doyle lost Sherlock Holmes to the Strand magazine. Someone once said that the three greatest creations of popular culture in history were Mickey Mouse, Sherlock Holmes and Superman. And here with Superman, a whole artform and industry constellated around the character. The tragedy is how the creators were excluded from Superman’s success, and spent most their lives impoverished.

PINKHAM: Did you get “Spiegal and Schumacher” not even knowing their character is a success long after the fact from those Siegel interviews?

VEITCH: Yeah. In an early interview, Siegel reprinted a letter from one of those early DC guys. DC’s in the process of negotiation for the Fleisher animated series, there are Superman books everywhere, toys everywhere, the comic sells in the millions. And this guy writes a letter to Siegel saying that “Yes, we know you are due a certain amount of royalties for any use of Superman outside of the comic, but we’ve actually lost money on the character.”

So it really wasn’t hard [laughs] to come up with tragic elements for my Spiegal and Schumacher characters. I was talking to a friend of mine who worked in production up at DC in the mid-’70s. And his first week there they called a big meeting. The police came and showed a picture of Jerry Siegel, and they said, “This man threatened to bomb the office building. If you see him or see any strange packages around [laughs] just let us know.”

There’s also a story, in Joe Simon’s book, that Siegel at one point went around and told everyone that he was going to dress up as Superman and jump off a certain building at a certain time, and everyone showed up ... but he didn’t do it. But it kind of pointed at how desperate he’d gotten. Unfortunately, at this point we don’t really know why he was desperate, other than the fact that he was royally screwed. I don’t know anything about his personality make-up or anything like that.

And having had a good taste of being a work-for-hire cartoonist, working under the system that was essentially set in motion by the rape of Siegel and Shuster 35 years before, I saw it as a worthy endeavor to bring this up. I think there’s a couple of points where I went a little too far; I could have been a lot more subtle and been a lot more effective. But, again, there was a certain deep anger in me about all this that needed to come out.

PINKHAM: Given that anger, how do you feel working for Tekno Comix?

VEITCH: [Laughs.] I’m not really “Roarin’ Rick” when I work for Tekno’Comix, I’m “Whorin’ Rick.”

I think the big difference is I’ve grown up, so I don’t need to connect with Tekno Comix on a personal level. When I went to work for DC, it was still that little kid who loved the Julie Schwartz superheroes. And when I went to Marvel, I had deified Stan Lee and Jack Kirby. That gets trampled out of you. Now I realize that I’m nothing but a well-paid technician for Tekno Comix. On an emotional level, I’m mature enough to go, “Yeah, that’s all it is. It’s a job: work-for-hire, and I’m getting paid pretty well.” But I’m not going to plan my long-term artistic need around them. I just can’t. If they went belly-up, I wouldn’t shed a tear. And if they become the next Sony Corporation and make a lot off my work I won’t feel bitter, either.

PINKHAM: In Maximortal 7, your brother Tom writes in the letters column: “I’m disturbed by the racist subtext: ‘True Man’ as a blonde blue-eyed Aryan type vs. the evil Jewish money-man. ‘Sydney Wallace’ could be a cartoon face right out of Nazi propaganda. The same kind of prejudices marred the otherwise excellent Bratpack.” What was that about? You reacted pretty hotly [laughs].

VEITCH: That’s the neat thing about being a publisher — you get the last word! I think it’s part of a conflict we’ve been having for years about the nature of our shadow sides, using “shadow” in the Jungian, psychoanalytic term. Which is to say, the dark side of the ego that is an essential component of the human race. Tom and I used to get into, call them arguments or philosophical give-and-takes about the nature of the shadow. Ultimately, he claimed he didn’t have a shadow and that he’d transcended his dark side, and I was only too obliging to point out that I thought he was full of shit! This is his response: looking at Maximortal for a shadowy, unconscious side to my fantasies but perhaps revealing his own soft spots in the process. He kind of let fly with his poison pen, which he’s famous for. But hey — it’s all in the fun. It’s not like we’re mad at each other; it’s just a weird game of “chicken”; he likes to write letters like that [laughs]. It’s not like we’re mad at each other; it’s just a weird game we play.

PRIORITIES

PINKHAM: Which has priority with you, Rare Bit Fiends or the Heroica?

VEITCH: Right now, it’s Rare Bit Fiends. Rare Bit Fiends is closer to high art than anything I’ve ever done. I’m just pouring my heart out. I could actually see myself doing Rare Bit Fiends until I die. It would be kind of amazing to leave record of human dreaming in the form of comics.

My approach to Rare Bit Fiends is like being a painter. The days I spend drawing comics of my dreams are like being in this deep and meditative state. I find it very rewarding personally. I’m getting a deeper and deeper understanding of what I am.

Rare Bit Fiends is art. It’s not a commercial thing. Right now it is kind of like a commercial vehicle—getting it up and running in the direct sales market, getting it printed, all of that. But the dreamwork itself is what’s important. I kind of feel I’ve found my “thing.”

PINKHAM: Do you think it’s gotten you past ideas you may have had about what “has” to be in a comic book?

VEITCH: Absolutely. It’s completely experimental. It’s more poetry than entertainment. In that sense, sure it’s going to be difficult finding a decent-sized audience to support it. But I’ m not going to worry about that; I’ve got a feeling it’ s all going to work out. At the same time, what’s neat is that I’ve created a comic book that’s absolutely impossible to license.

It’s something that is a pure comic, and is pure art. It just can’t exist in any of these other bastardized forms that stormed comics in the ’70s and ’80s. With Rare Bit Fiends, I feel as if I’ve hit upon something that’s right for comics as a form, not comics as a commodity.

PINKHAM: Has it been a conscious decision to make most of the dreams so far one page in length?

VEITCH: You have to remember, I do this comic in my sleep! [Laughs.]

PINKHAM: Are you getting more sensory information than you show, making the decision as editor to convey everything in one page?

VEITCH: I tend to dream, or remember my dream, in small bits. I’ve got these prose dream diaries I did when I was younger and I used to have long all-nighters. My brain doesn’t work like that anymore. I know I’m still dreaming all night, but what I remember … It might be a function of old age, I’m not sure.

PINKHAM: [Laughs.] In an interview you did with James Pascoe, you say there is plot and character development to be found in the comic if you look through the faces of the characters to the archetypes behind them — these archetypal characters continue to be expressed in various ways throughout the series.

VEITCH: I keep dreaming about going back to the old mill, which is the place my father worked when I was a kid. That symbolizes the Rick Veitch father complex [laughs]. You’ll notice in those dreams there’s always some real problems going on. There’s a lot of emotion and desperation that’s involved in it. And I bet you, if I do this project over time, the mill will keep coming back. And people who stick with me for years and years will go: “Oh, Rick’s back in the mill again! He’s dealing with his dad again.”

PINKHAM: You could organize Rare Bit collections by theme: “The Old Mill Book,” and so on.

VEITCH: I was thinking if I ever do a CD-ROM collection, it would be a way of organizing dreams in series. You could press “self-publishing” and get all the Dave Sim dreams.

And I open up every issue with the cat; I have the cat dreams regularly.

PINKHAM: You’ve called it a “rare bit fiend”?

VEITCH: Right. I called it “Rare Bit Fiends’’ That was more for entertainment value than anything else, but I do dream about the cat a lot. In fact, each time I dream about it it’s seen in a different light. In the first dream it’s referred to, it comes down and jumps me, rips me apart. Then it’s a thing that dies and vomits out stuff that morphs into another cat. And then, with the third one it’s standing up there, giving a course on dreams on its hind legs. There’s another one where there’s about fifty cats, all licking me [laughs]. So, I’m not sure what it symbolizes, but it seems to be something that’s evolving.

PINKHAM: Is there a danger that you may stop dreaming about things which are important to your psychological well-being; which either hold no interest for your audience, or could embarrass you in front of them?

VEITCH: The thing is, I don’t create strips out of all my dreams. There are definitely ones that I’m not ready to share. So, I hate to wreck your fantasy; (whispering) don’t tell anyone, but I actually do ’em while I’m awake [laughs]. I’m only sharing the ones I want to share.

PINKHAM: I was wondering if by staking your career on them, you could eventually end up blunting your dreams with expectations — “Oh, shit... Time to think up some more dreams!”

VEITCH: If I ever run dry, I can go back and do 10 issues of Rare Bit Fiends from my 20s. My real interest in that project would be to see how they vary in content and tone from what I do now, and also to see what they prophesied. I’m quite sure there’s a prophetic element to dreaming. I’ve thought about it; in fact, I may have sent you a dream I had where I saw myself at 20 years old. I’m at Jack Kirby’s funeral, and I look up on the mountain top; there’s a figure standing up there, and at first I think it might be my neighbor, but as I look closer I see that it’s me, but 20 years younger. In the dream, I just zoom in on my eyeball, and the color and pattern of my eye became this incredible hypnotic kind of thing. And I was struck by that dream. I kind of saw that as a sign that it might be a good idea to actually do that project.

1963: THE SIMULATED SWEATSHOP

PINKHAM: In the first Rare Bit Fiends, you tell the story of what went on behind the scenes of 1963.

VEITCH: I should tell the whole 1963 story, because it’s actually a kind of interesting time. Bissette and I figured we needed to self-publish, because obviously the Tundra thing wasn’t going to work. Tundra hadn’t been sold yet (to Kitchen Sink), but Steve and I had both come to the conclusion that Dave Sim was right. Dave Sim had warned us about every pitfall, but we went ahead with Tundra anyway. Finally, it began to make sense; we really wanted and needed to take control of our own fate, and take responsibility for business decisions. But we were missing the capital. We were both making decent livings, but we needed some sort of capital, because publishing just doesn’t happen without it.

So, we were just sort of thinking about that when Image came along. I think everyone was surprised. Those guys all left Marvel, formed Image; and it was really happenin’. We were excited by the fact that here were some creators that didn’t stay at their publisher and turned around and started their own thing, and actually continued the big sales, gouging market share out of the industry giants. That’s a key point in the evolution of the comics business.

Anyway, those guys were coming along, and we saw in what was happening, the good potential being, “Hey, here are some creators with responsibility and control over the business side of their comics.” At the same time, I’m a little scared for them, ’cause I’d just been through the Mirage and Tundra explosion — gold rush mentality and capital coming in combined with poor organization; we were crawling out of the trenches. I had just gotten an after-the-fact work-for-hire contract [laughs] from Mirage. Some crazy maniac at Mirage I’d never met, in some strange position of power down there, was calling me up and threatening that if I didn’t sign over work I’d done years before I would never see any more royalties.

PINKHAM: Ouch.

VEITCH: Worse, the contract is more wretched than anything even DC had ever done to me.

PINKHAM: Eastman and Laird are friends of yours, right?

VEITCH: I’d like to think of them as friends.

The pressures they were under I understood. I felt bad for them, for the positions they had found themselves in: possessors of incredible means, and owners of a rich vein of comic book culture, namely the Teenage Mutant Ninja Turtles. But on the personal level, they were in an organizational nightmare.

It seemed they’d lost the human connection that had been such a part of why the Creators’ Bill of Rights happened, and it was like the flip side of being so generous to all of the people around them right after they’ d hit it big.

So, me getting that horrible contract and being ragged by some junior-level flak, whom I’ve never heard of, really kind of ended the possibility of me working with them.

PINKHAM: Did you have to sign?

VEITCH: No, I never did. But I know a lot of other people who are worse off signed.

What they’re afraid of is they’re going to get sued — for good reason. The way the laws are set up in this country, you have to protect yourself from lawsuits. That means having a contract with every dot on the “i” and every “t” crossed. If they ever want to sell The Turtles, it may cause a problems that they let people like Dave Sim, Rick Veitch, Steve Bissette, Michael Zulli and a number of others draw their own versions of the Turtles on a handshake deal.

PINKHAM: Although you’d think Mirage would have no problem outlasting any freelance cartoonist’s pocketbook in court …

VEITCH: Honestly, I don’t think it’s Peter or Kevin; It’s lawyers sitting around looking for something to do. [Laughs]. You know, I’m glad it didn’t happen to me.

PINKHAM: Back to 1963.

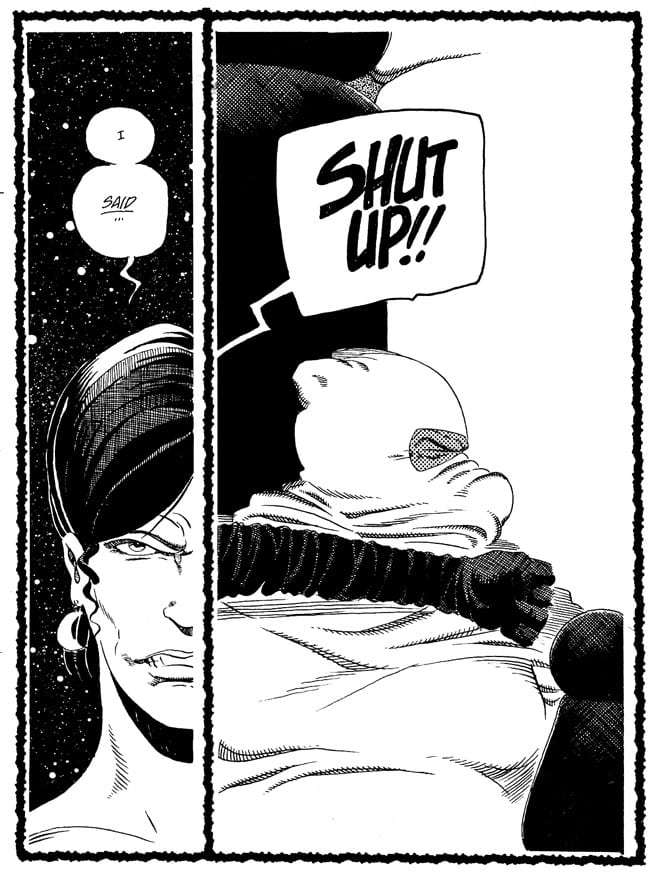

VEITCH: Out of the blue, Jim Valentino called Bissette; he wanted to spread the gravy around to other creators. Jim wanted to bring Alan in. I think it started out he wanted Alan and Steve, to do another Swamp Thing, and Alan just wasn’t interested in Swamp Thing at all. He had this vague idea to do a superhero comic deadpanned exactly as comics used to be. It was real vague, but it was enough for Valentino to go, “Yeah, Sounds great!” And he sold it to Image. Early on, they decided they wanted me in. Again, I think a lot of it was I’m good at … production.

PINKHAM: [Laughs.] “Now all we need is someone who can do the work.”

VEITCH: So, early on they called me, and Alan overnight created the world of 1963, all six titles. It took Steve and me awhile to catch on to what he wanted. We were doing the production sketches and we faxed them over to him: “No, no, Rick ... That’s too good [laughs]. Do them looser.” Pretty soon, as it picked up, we became a “virtual bullpen” on the phone and the fax machine. He became “Affable Al,” I became “Roarin’ Rick” (which actually was my nickname in the Hero Comics I did as a kid), Bissette became “Sturdy Steve.” And creatively, stuff began to happen. It came together pretty quickly.

Bissette and I went down to San Diego that year, and we still hadn’t agreed on the deal. One of the reasons was Jim Lee wanted to work with Alan; he very much wanted to be brought in on the comic. So, the idea began to come together of Lee doing the Annual to end the whole project. Our characters from 1963 and modern, 1993 Image superheroes having a big bash —

PINKHAM: So you guys weren’t going to be the art team for the Annual.

VEITCH: Right. We were going to do the first six.

But we still hadn’t cut the deal; Steve and I were still afraid of it. We were talking a lot with Valentino, who was terrific, really working his balls off to bring the other Image guys around to what we wanted to do. We were one of the first outside projects Image took on, and those guys were having a hard time agreeing on where they were going. There were seven of ’em, having this massive success, trying to get a hold of it, trying to come up with some sort of direction. They’re hiring people, and starting organizations — a lot of confusion. And we’re looking at this, going: “Oh, man ... it’s Tundra all over again!” [Laughs.]

We’re a little afraid of it, and we hadn’t decided— and a couple of points were dangling, and one of ’em was Jim Lee; if he was really into it. And I’m walking around the dealer room in San Diego when up runs Don Simpson: “Hey, man — you’ve got to get up to the Image panel right now! They want to talk to you. Grab Bissette.” So Bissette and I go up there, and there’s like 2,000 people — I mean, it’s a mob scene. McFarlane’s doing his Oprah Winfrey shtick, he’s got the audience eating out of his hand. I mean, it’s obvious they had really tapped into something. And here’s Steve and me, in the back of the room, trying to cut the deal with the guys on stage —

PINKHAM: Over a microphone?

VEITCH: No, through hand signals. You know, like Valentino would run down to talk to us, then he’ d run back, then he’d send someone else down. Finally, Lee came down, and we asked the question: “Does Jim Lee really want to do the project?” So, he said: “OK, listen. If we can announce it right now — [laughs] “I’m on the project.”

PINKHAM: They wanted to get this all wrapped up oh the spot, so they could announce it on the panel?

VEITCH: That’s it. It was a huge pressure situation. Steve and I, we were completely out of our element. We’d never had to deal with anything like this.

So, we talked it over and after about five minutes we signaled “OK.” So, they announced it and a big cheer went up, then they rushed us up on the stage. They talked a little bit more, then Liefeld started throwing T-shirts and hats and things into the audience. The audience surged the panel, and the security guards were pushing us out the side door [laughs]. The crowd came up on to the stage — Bissette and I were like “What happened?” [Laughs.] We were flabbergasted by the whole crazy situation we’d been caught up in.

PINKHAM: Sort of like being signed to Apple Records during a Beatles concert.

VEITCH: But we still didn’t have a final deal. It was basically a handshake, and we started work. The terms were outrageous: Image makes 10 percent of the profit, Valentino’s Shadowline gets 10 percent of the profit, and the creators get the other 80 percent — which is fantastic. It was like a dream. At the same time, Alan and I were in such financial straits, we needed some sort of funds. We needed a loan, which Valentino provided through Shadowline, sort of bankrolling a really small page rate — 75 bucks a page — just enough to keep us afloat until some of the profits came in.

And so we came back to Vermont, and called up Alan — bing, bing, bing — and started work. Steve and I rented a little cabin right between our houses (we live 30 miles apart) and a couple days a week we’ d meet at the cabin and we’d start blastin’ out the comics, Alan saying, “You’ve got to draw two or three pages a day.

PINKHAM: To give it that rushed look.

VEITCH: “… Blast it out, like Ditko and Kirby.”

PINKHAM: Under those conditions, I hope he didn’t give you one of his usual scripts—unless he meant reading two or three pages a day.

VEITCH: It was all done Marvel style. Affable Al would call up and sort of describe what would take place. Then we would fax him finished pencils, which he would dialog — and if you read 1963, dumbing the dialog down, which is difficult for Alan.

PINKHAM: Well, after flipping through Violator…

VEITCH: The mistake we made — actually, I can remember a lot of mistakes. One of the mistakes we made was that Steve and I took on editorial and production of the whole series, with no pay. We figured this thing was going to pay off, and pay off big. So we ended up working our balls off organizing, making sure the thing happened. Valentino was right there all the time; he couldn’t have been better, handling everything on the Image end. Anything we needed, he took care of. But we just — we should have known better. Organizing a bunch of crazy artists all over the world, and a writer who’s a world-class eccentric… [Laughs.]

PINKHAM: So the simulated sweatshop was becoming a real one.

VEITCH: What’s funny is it really kind of did evolve into that. I don’t think Alan was really ever connected with the thing like he gets with his real projects, like From Hell. As we got deeper into it, he seemed to become disengaged; we were stuck with a lot of the letters pages, and ads, shit like that, that he should have been doin’.

Steve and I sorted out whatever problems were coming from Image. You know, it was crazy. They were in this protoplasmic stage of massive success, kicking the shit out of Marvel in terms of market snare. And of course it fueled the speculator bubble. Steve and I didn’t understand what the speculation was all about — because none of our comics were really speculator comics —but we caught it. We had our books out just as the bubble burst, so the first two issues of 1963 had ridiculous orders — I think the first one was 600,000.

PINKHAM: Jesus [laughs].

VEITCH: The second issue ordered 500,000. They were massive, massive — Although the big mistake we made, this was the main thing: we didn’t understand promotion and advertising, how important it was to the Image cachet. If you go back and look through the distributor catalogs, there’s massive blocks of full-color Image ads: “Man! 20 pages of full-color Image ads …” We never did that. We didn’t understand how important it was, and we didn’t have time because we were just barely holding the virtual bullpen together, getting the books out on time. I think we were the only Image book ever to ship on time — ever.

So the creative end really came together. Valentino, in a last desperate act to promote the book, hired on Larry Marder to do an ad campaign, although it was very late in the game — the book’s about ready to come out. And he was able to identify a certain amount of the problems and address them. I think the sales of ’63 could have been better in the retail outlets.

SIM AND SELF-PUBLISHING

PINKHAM: You’ve said Dave Sim has been a big influence on your move to self-publishing. Given his idea of wife and family as vampiric drains on male artistic potency, is self-publishing a bachelor’s art?

VEITCH: I can tell you, from everything I know about him — I’ve hung out with him some — he is expressing things that he’s discussed informally with me. That’s one of the reasons why I found the “Reads” novel so powerful. I’ve been hanging out, talking self-publishing till four in the morning — three or four of us sitting in the hotel room, all blitzed out. He would start going off about this outrageous stuff which he really seemed consumed by and, when I saw him actually putting it down on paper, “Yeah, he’s actually getting there, he’s actually going public with it!”

PINKHAM: Yet, according to him, you should be failing, or will soon fail, as a self-publisher. You’re married; you have a family…

VEITCH: I don’t think he’s only applying what he’s talking about to self-publishing. I think he’s talking about what he sees wrong with the world. There’s no doubt, in the case of a self-publisher, things might be easier if you’re a bachelor. There’s plenty of cases on record of interesting creative work that got derailed by marital pressures. But I know a lot of single creatures that can’t get it together [laughs].

It does make it more difficult for me. I’ve got to ultimately set up Rare Bit Fiends at 10,000 a month to maintain the same middle class income, as if I were doing, say the typical DC book. That’s what I’m shootin’ for, but I’ve got a long way to go in establishing Rare Bit Fiends.

PINKHAM: Which of Sim’s ideas are particularly important to you?

VEITCH: That all companies are bullshit, [chuckles] I learned the hard way. I think when I worked for a company, I was trying to connect with it on an unconscious, emotional level. That was one of the reasons why I always come away from the experience feeling kind of violated — although I often was violated [laughs], I wasn’t cool and professional enough to say, “Oh, it’s just business.”

The whole process led me to Tundra, where it still got out of hand. It was a splash of cold water in the face. Steve and I, both of us, came out of that process saying, “This sucks. We’ve got to get control.”

The other thing that impressed me was at the end of the second meeting of the Creators’ Bill of Rights, and how Dave pointed out to Peter and Kevin what he thought was bullshit about the studio they were setting up — he predicted a number of things which sounded really outrageous at the time, but which came true. You know, one of Dave’s problems is he’s so blunt; he pisses people off and drives them away so they don’t even try coming to grips with what he’s talking about. He builds terrific coalitions, then tears them down on ideological grounds.

Dave’s a real piece of work; when Hunter Thompson proclaimed, “When the going gets weird, the weird turns pro,” Dave answered the call! [Laughs.] That said, I can’t really agree with his rant against “merged permanence” in #186.

What most people miss is that underlying the gender issue is his condemnation of human feeling. To me, the heart is very important. A lot of the problems of society can be traced to the fact that people are out of touch with their feelings. There’s a whole historical context, beginning with rational humanism, scientific method, and the Enlightenment, where the rational mind kind of took over the emotional needs of the heart. It seemed like such a brilliant idea. In the 1700s, 1800s, all these scientific discoveries were being made and industry was forming, machines were being created, and society was being organized into a workforce of consumers. By the 20th century, we’ve had two horrible world wars, and we’ve got humongous ecological problems that trace back to the Industrial Revolution. It’s a catastrophic situation that could have been avoided, I think, if way back during the Enlightenment folks would have allowed their hearts to help make decisions. When Henry Ford created the Red River assembly line and populated the planet with automobiles, he wasn’t listening to his heart or the planet’s real needs, he was rationalizing the immediate need for transportation.

PINKHAM: In the Pascoe interview, you tie these developments to our reliance on text.

VEITCH: I think reading linear text puts you in a linear thought process. It’s very single-minded and goal-oriented. The thing I like about comics is that they impart information more holistically and holistic conceptualization is what we need in this day and age. Napoleon was a linear thinker. So was Hitler.

PINKHAM: Sim takes a real Enlightenment point of view: women are animals, part of man’s natural habitat to be tamed by order and ingenuity.

VEITCH: The war of the sexes is between feeling and reason. But it’s just one battle in all of humankind’s war with itself — or search for itself. Jung said there were four functions of the human psyche: thinking feeling, intuition and sensation. It seems none is intrinsically superior to the others. The target should be a balance between all four, as if you were balancing your senses; you don’t cut your ears off because your eyes provide you with everything you need.

I suspect that the optimum way for humans to exist is running all four of these functions.

That said, I think of a lot of things Sim pointed out about the problematic aspects of emotion are true. But there’s a difference between feeling and emotion. Emotion, I would define as something raw, something out of control, something unconscious. Whereas feeling can be a well-tuned instrument by which we can get in touch with things that we cannot see, like the macro-ecological systems that are beyond anything the rational mind can compute.

In my own case, having a child was the thing that helped me open my heart and get in touch with my feeling side. The situation forced me to mature. That may be what Dave needs [chuckles]. It worked for Gary [laughs].

Dave’s out of balance, but he’s one of the best things that’s happened to comics. He appeared at the beginnings of the direct sales market, and probably made better use of its potential than anybody else, in terms of creative output. He’s hard-bitten, but he’s created a valuable franchise doing exactly what he wants, and through trial and error, he’s streamlined it of most of the fat. Now, I think he’s applying his incredible powers of deduction to try to fulfill the real promise he saw in the direct sales market before it was hijacked by the large publishers.

PINKHAM: So, Sim’s imbalance provides an element of balance to the comics industry?

VEITCH: Because the industry needs smarter artists. Any cartoonist who can write and draw should self-publish. What you need to learn to self-publish is so minor compared to any of the other skills you have to learn to draw, write or letter a comic book, that it’s just piddling stuff.

You know, the real fulfillment of the direct sales market will be the day Marvel and DC lurch into Walmart. I think the big publishers — Marvel and DC, Image and a few others — will end up trying to sell comics only to mainstream consumers. Now, you can’t sell Rare Bit Fiends to the mainstream, you can’t sell Vertigo, or Fantagraphics. This could be a real opportunity for the alternatives to inherit the wreckage of the direct sales market when the big guys move out.

Just imagine what comic books might be like with 20 or 30 self-publishing houses in a solid position, like Cartoon Books, Aardvark-Vanaheim, Colleen Doran, James Owen, Spider-Baby ... and hopefully King Hell [chuckles]. I mean, just think of the stability and integrity for the art form that that kind of structure would create. Focus on the importance of the creative output first, rather than the corporate needs which, except for a few bright spots, have dictated the whole history of comics in America.

PINKHAM: The hard part is convincing retailers they can survive without that system.

VEITCH: Well, they can’t survive with the system. They’ve all got crates of Marvels in the back room they’ll never sell. Hopefully, some of them will wake up. I’m surprised at how long it’s taken. Every summer some marketing genius [laughs] at some giant company figures out some way to stick retailers with jillions of hideous books that won’t sell.

PINKHAM: “Universes!”

VEITCH: The poor retailers take it in the neck. I have to say, I profited from that; a lot of ’em are stuck with copies of 1963! [Laughs.] The difference is that I didn’t realize until after it happened what had really gone down.

I think some retailers are moving towards something akin to self-publishing; we call them “self-retailers.”

PINKHAM: You mean mail order?

VEITCH: No, people who are creating comic-book stores based on what they like, not on what the market is putting out. It was Larry Marder who came up with the concept of “self-retailer.” It’s the equivalent of self-publishing; the guy who runs the comic store, he orders only what he really likes. And you know, across the country, if there were 400 or 500 of these self-retailers, self-publishing would take off like a shot. It that comes to pass it will fulfill the potential we all saw in the direct sales market in 1978!