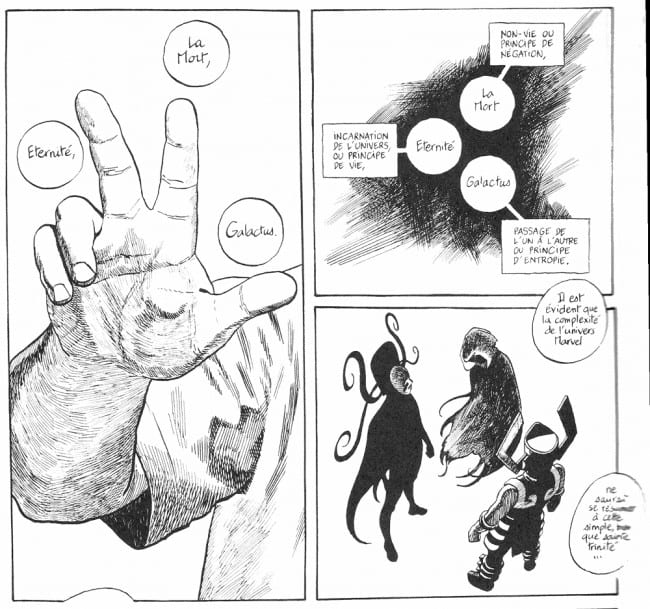

Toward the end of the fourth, and so far last, volume of Fabrice Neaud’s comics diary, Journal (4) (2002), one of the author’s friends, the gregarious Denis, holds forth on the structure of the Marvel Universe. He explains succinctly the conceit, developed by John Byrne during his '80s run on The Fantastic Four, of a core trinity—Death, Eternity, and Galactus—constituting the cosmic balance. Death personifies the principle of negation, Eternity the principle of life, and Galactus the passage between the two, or entropy.

The scene is the culmination of a book in which Neaud seeks to address the balancing of the scales that happens with time. After the emotional ordeal of his masterpiece, Journal (III) (1999), the fourth volume is concerned with how life goes on, healingly but also relentlessly. It carries the feeling of aftermath, describing life negotiated around a repressed, cooling emotional core. This is accentuated by the familial reality creeping in around the edges. Neaud’s grandmother suffers a stroke and forces him to face his alienation toward his family.

The book is subtitled "Les Riches heures", which recalls the Duke of Berry’s famous book of hours, illuminated unforgettably by the Limbourg Brothers, and denotes the cyclical nature of reality and the passage of time. Nothing is resolved in life, it just ends. Happiness is a question of how one negotiates entropy. In the end it is a cautiously happy book, sweepingly beautiful in its lush opening and closing passages—a structural idea imposed by Neaud upon his work to assert that negotiation in his life.

What we have here, then, is something almost unthinkable in American comics, at least until recently: an artist working at the most personal level, taking reality-based comics as far as anyone, and in doing so invoking the power of Galactus. And not the palatable original version from the work of the character’s creators, Jack Kirby and Stan Lee, but rather the one made by Byrne, an artist almost uniformly (if unfairly) reviled in American alternative comics. (Neaud also brings in Jim Starlin’s '90s work, which is held in even lower esteem.) “Denis” goes on to tease out the meaning of the blank, white panel backgrounds used as often by Byrne as almost to constitute an auteurial signature. He describes this “plane of manifestations,” in which the celestial entities of the Marvel Universe occasionally appear, as a space “before creation”—a potent metaphor for pre-conceptual reality that Neaud, as explained, attempts subtly to harness in how he writes his life in comics.

When I interviewed him in 2010, I asked Neaud about this, after we’d finished our main discussion of his new, augmented version of Journal (III) (2010). He explained that since superheroes had never held the kind of hegemonic sway over French-language comics culture that it has in the English-speaking countries, they had come rather to represent a stimulating alternative to the local mainstream for him and his peers. As “Denis” explains, Franco-Belgian comics lack the audacity and ambition to work in metaphors that broad.

Since then, Neaud has suspended his work in autobiography. His appropriation of real people’s likenesses landed him in trouble some years ago, causing what he has described as a personal and creative crisis. His 2000 short story, “Émile”, depressed and depersonalized, presents a dark reverse of the hopeful Journal (4)—the Death to its Eternity, so to speak.

After several years of low productivity, he now seems to have found a different outlet by returning to the ambition he had as a young cartoonist of working in the fantastic genres. Earlier this year, the first volume in a science fiction series called Nu-Men was published by Quadrants. Owned by Mourad Boudjellal—best known as the owner of the hyper-commercial upstart pop publisher Soleil—Quadrants specializes in auteur-driven genre comics. A perfect fit for Neaud’s drastic shift in register, his reverse Mazzucchelli.

The premise of Nu-Men is kind of boilerplate. The setting is a near future where North American civilization has been wiped by a huge volcanic eruption in the Yellowstone Park, and Africa’s population decimated by a pandemic. This has left an increasingly autocratic European Union as one of the centers of world power, fighting clandestine wars abroad and securing its borders against the huge waves of migration set off by these upheavals.

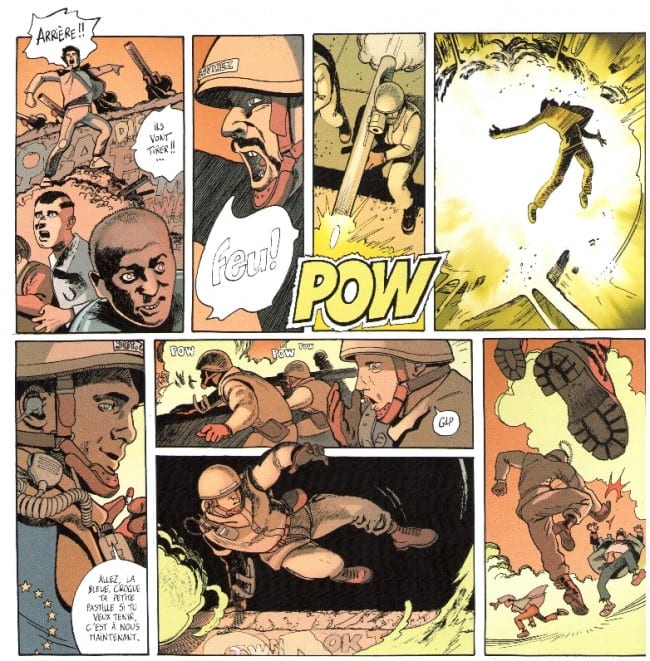

The protagonist is Sergeant Csymanov of the Common Territory Defense Force, a military unit charged with eliminating terrorist threats to European security. A routine operation goes awry when his squad witnesses a strange para-technological manifestation. As readers we learn that this ties into top-secret experiments of the super-soldier type so well-known to readers of superhero comics, as well as the nebulous machinations of the scientists behind them. And in the margins a rogue mercenary commander who looks like the original comics super-soldier Captain America’s arch-nemesis, the Red Skull, is making his own play.

The protagonist is Sergeant Csymanov of the Common Territory Defense Force, a military unit charged with eliminating terrorist threats to European security. A routine operation goes awry when his squad witnesses a strange para-technological manifestation. As readers we learn that this ties into top-secret experiments of the super-soldier type so well-known to readers of superhero comics, as well as the nebulous machinations of the scientists behind them. And in the margins a rogue mercenary commander who looks like the original comics super-soldier Captain America’s arch-nemesis, the Red Skull, is making his own play.

It is hard to say from just the first volume what Neaud plans to do with his premise. The initial volume is a bit of a mixed bag. The political satire, which presents a typical European left-wing view of immigration policy, is solid enough, but a little predictable, while the media satire—personified by a trans presenter nicked pretty much wholesale from Chris Tucker’s character in Luc Besson’s The Fifth Element—is kind of trite.

Another problem is that Neaud’s heavily photo-referenced, naturalistic artwork works less convincingly than one might expect. In his lovingly rendered autobiographical work it performs the essential task of representing a recognizable external reality, while at the same time allowing for the nuance of characterization necessary to convey that of inner life. Here, it is put in the service of sprawling tableaux of urban unrest and natural catastrophe; it has to fathom futuristic high-tech environments and post-industrial squalor and, hardest of all, render a believable future. Plus it has to convey action.

Although never a natural, Neaud drawing chops are impressive—the result of years of hard, focused work—and his solutions to storytelling problems are often inventive. He rises to the task with admirable brio, never making things easy for himself. One senses that he really enjoys the challenge. But his characterization simply remains too stiff, his articulation of space at once too rigid and unclear, and his panel-to-panel narration in action sequences too choppy, fully to carry the illusion of reality. He is no Bryan Hitch, never mind a Katsuhiro Otomo.

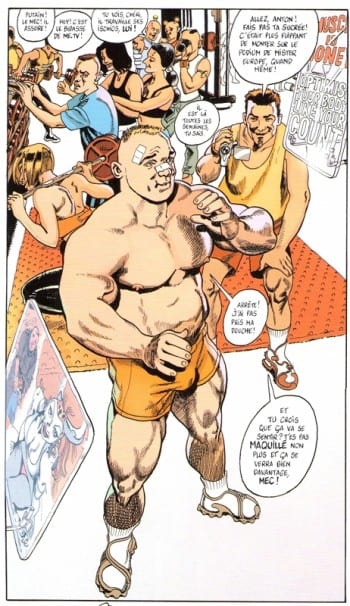

On the other hand, we are dealing with one of the smartest cartoonists around, and it does not fail to show. Those familiar with his work, and thus his preferences in men, will recognize just how enthusiastically he appropriates the scopophiliac tendencies of a set of genres historically disposed toward self-indulgence. In a direct challenge to the most strongly heteronormative area of comics, he lays on the beefcake as he likes it: muscular guys in various states of undress, with a preference for tight-fitting sweatsuits and foamy sneakers. In this respect, the morally centered Csymanov appears as a heroic, human projection of Neaud’s fantasies. An intelligent and both emotionally and socio-politically resonant use of the genre tropes at hand.

Beyond that, his blend of hard science fiction with the kind of high fantasy accents benchmarked in comics by Jodorowsky and Moebius in The Incal cycle is achieved with great confidence. And it becomes all the more interesting as it is slowly revealed that this might not actually primarily be a science fiction story after all, but something more in the spirit of Byrne and Starlin, with elements, perhaps, of Grant Morrison and even Frank Miller. It is too early to say, but the prospect of somebody with Neaud’s ability engaging entropy in a superheroic register is an intriguing alternative.