The impact of women on the underground and alternative comic scenes of the late 20th century has been the subject of extensive academic research in recent years. This scholarship has helped shed light on the contributions of women to a historically male-dominated field. Academics such as Hillary Chute, Margaret Galvan and Leah Misemer have written about the political and artistic significance of works like Wimmen's Comix, Tits & Clits, Wet Satin and Manhunt in publications ranging from iNKS: The Journal of the Comics Studies Society to the New York Times. Another prominent figure in this field of study is Sam Meier, who was among the first to examine the political dimensions of Wimmen's Comix and Tits & Clits in depth.

Graduating from Harvard in 2012, Meier wrote her undergraduate honors thesis on how those who contributed to Wimmen’s Comix (1972-1992) and Tits & Clits (1972-1987) conceptualized the ideological elements of their art. Using interviews to bolster her sociological study, Meier was the first (whom I can find) to examine the difference between Wimmen’s Comix and Tits & Clits deeply or analyze the distinctions between the political engagement of alternative women cartoonists of the '70s vs. the '80s. After receiving two grants from Harvard, Meier went to California to further interact with the cartoonists with whom she originally communicated for her paper. At the 2013 University of Florida conference “A Comic of Her Own”, Meier discussed her undergraduate and postgraduate research on a panel with Margaret Galvan.

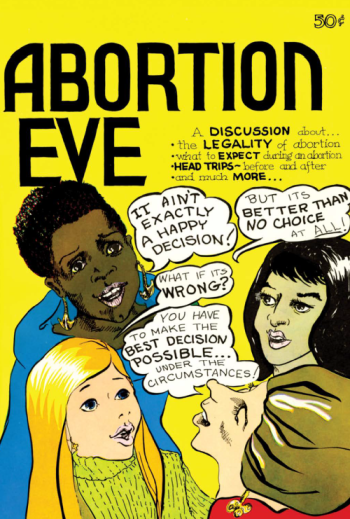

In 2014, Meier forged a closer connection with Tits & Clits after Joyce Farmer, the co-creator of the series, contacted her. Indicating the poor health of fellow co-creator Lyn Chevli, Farmer urged Meier to stay with her in Laguna Beach in order to speak more with both artists and sift through their archives. Meier accepted Farmer’s invitation, and would go on to publish research about that series and Abortion Eve (1973), a pro-choice one-shot also by the two artists, for venues like Bitch Media, the Comic Book Legal Defense Fund and the Hooded Utilitarian. Her prolific writing about these comics and extensive experience with Farmer’s and Chevli’s archives informed her editorship for the recent Fantagraphics omnibus, Tits & Clits 1972-1987—collecting the seven issues of the series, along with Abortion Eve and an interstitial 1973 one-shot, Pandora's Box Comix—for which she also authored an extensive introduction.

I spoke with Meier about what Harvard thought of her research on “trash” like underground comix, whether she viewed her work on Tits & Clits as political (a question similar to one that she asked individual creators for her undergraduate thesis), and what the value of Abortion Eve is for modern audiences. An oral history of Tits & Clits with several of its original participants can be read here.

-Edward Dorey

* * *

EDWARD DOREY: Before we begin this interview fully, I would like to look at some cliches of writing about comics from the 2009 Harvard Crimson article “Hitting the Comic Books”. The article begins by describing a scene from the highly underrated Watchmen. Then the piece discusses how comics are serious because films based on comics are now getting prestige - specifically The Dark Knight. Later, the writers include a statement from a comic book store owner who opines, “In general the best comics nowadays are much better written than the comics written 20 or 30 years ago.”

This is an Onion headline from 2012: “Comics Not Just For Kids Anymore, Reports 85,000th Mainstream News Story”. In his book Arresting Development: Comics at the Boundaries of Literature, Christopher Pizzino uses this headline to illustrate how, despite decades of comics having become legitimate (this discourse goes back to at least Maus), comic writers, comic artists, and comics themselves will always sit at an uncomfortable liminal point between high-brow acceptance and disdain.

While at Harvard, did you feel that studying comics, especially ones like Tits & Clits, was taken seriously by faculty, or did you ascertain that many did not respect your undergraduate research?

SAM MEIER:I had varying experiences at Harvard depending on the department I was working with. My thesis was written for the Sociology Department, and I concentrated in the field. (“Concentrating” is the Harvard word for majoring.) Everyone in the Sociology Department took my research seriously. In either my freshman or sophomore year, I shared my desire to do something with comics for my undergraduate honors thesis, which, initially, I wanted to do in graphic narrative form. The sociology department was on board with my plan.

However, when I went to the Visual and Environmental Studies (VES) department (which is now called the Department of Art, Film, and Visual Studies) to see if I could get a faculty member to co-supervise my thesis for a joint concentration, no one was willing to advise me. They told me that none of the faculty in VES had expertise in cartooning, and no one taught the subject. I took a couple of courses in VES that focused on animation and drawing, but the VES faculty at the time told me there wasn’t anyone who could ensure that my thesis met departmental expectations and that it would compromise the artistic integrity of the work to address sociological concepts or theory in a graphic narrative.

Right around the time that I was graduating, Harvard invited Peter Kuper of World War 3 Illustrated to be a guest lecturer and began paying more attention to comic books, cartooning, and graphic narratives. My sense is that VES changed around the time that I was leaving the university in 2011-2012.

My thesis advisor, Matthew Kaliner, never questioned my interest in comics, though he was unfamiliar with underground comix. When I gave him some, he was embarrassed by the content. We still joke about how much he blushed when I showed him Zap Comix for the first time. However, he backed my studying them and was a huge help to me. I’ll always be grateful for Matt’s support, and he continues to be my friend.

In addition to Matt’s outstanding advising, Katherine Stanton was at Harvard during the time that I was there. In my freshman year, I took her course on alternative comics mentioned in the Harvard Crimson article. During my junior year, when I was getting ready to submit my thesis prospectus, Stanton connected me with Hillary Chute, who, a year before, had written Graphic Women, which she worked on while she was a Junior Fellow in the Harvard Society of Fellows. Chute offered me support, too, and helped me refine my initial ideas for my thesis. A fellow student, Shaun Vigil, offered me advice on researching comic books based on his own 2011 thesis on the Spider-Man comics of the 1960s-1980s.

My initial idea for my thesis was to do a content analysis of Wimmen’s Comix, supplemented by interview-based research. I was lucky that Schlesinger Library [on the Harvard campus] had most of the issues in their holdings and that the staff at Schlesinger helped me access these comics and related materials. The sociology department gave me a small mid-thesis grant to buy some of the copies of Wimmen’s Comix and Tits & Clits that I could not find at Schlesinger.

I don’t think Harvard had any issues with my work. My thesis was well-received by the Sociology Department. It was nominated for a Hoopes Prize [an annual award for meritorious scholarship or research] and received a departmental award, the 2012 James A Davis Prize for an Exemplary Thesis in Sociology. After I completed my thesis, I applied for and was granted two different sources of postgraduate funding from Harvard: the Alex G. Booth Fellowship (a travel fund) and a research grant from the Schlesinger Library.

Overall, my experience at Harvard was that the Sociology Department said, “You can do whatever you want,” but the VES department was not as supportive. Sociologists are interested in deviance, subcultures, and fan cultures, so studying underground comix and feminism seemed to make sense to the faculty there!

How did Harvard’s backing compare to other institutions? Did you hear students at other universities lament how their faculty did not bolster them?

None of the scholars I knew said that. But they had been people who had managed to write about comics at their respective institutions. So there is a sampling bias because I did not talk to anyone discouraged from writing about comics or graphic narratives. I would not have met those people if universities had not assisted.

In your thesis, you note the multiple ways in which artists think that their work is political. You explore how, for example, those working with Tits & Clits view their work as “eroding the private/public boundary through art production.” Although you mention that artists working on Wimmen’s differed dramatically with regard to how political they see their work, you observe that many thought of Wimmen’s as a more “‘party-line’ feminist anthology than [T&C].” What drew you more into researching T&C over Wimmen’s after you finished your thesis? Is there something about T&C that appeals to you more?

It was mostly chance. Harvard awarded me the Booth Fellowship to visit many of the cartoonists whom I had interviewed for my thesis in person. I spent the summer of 2012 staying with, visiting, or meeting most of the artists whom I talked to for my undergraduate project.

Thanks to the fellowship, I was able to go to Laguna Beach to visit Joyce Farmer, Lyn Chevli, and Mary Fleener. I stayed at Joyce’s house for a few days. Joyce and I got along fairly well. Between 2012, when I finished my thesis, and 2014, several artists I had spoken to encouraged me to continue my undergraduate work and publish it. As you noted in your emails to me, little information was available about Wimmen’s Comix or Tits & Clits at that time, although Margaret Galvan and Ian Blechschmidt were starting to publish about series like those two.

In 2014, Joyce gave me a call and said, “Lyn Chevli’s health is actively declining. [Chevli had had various health complaints for a while.] If you want to write about me, Lyn, and Nanny Goat Productions [the company that Lyn and Joyce created and through which they self-published], the time is now. You can come out and stay with me, interview me further, talk to Lyn some more, and speak to other people I know in Laguna Beach. I will support your research.” I wound up taking Joyce’s offer. I quit my job, moved to Laguna Beach, and stayed with Joyce for a couple months. Then, I began conducting more serious archival research about Nanny Goat Productions at a variety of institutions.

What led me to focus on Tits & Clits was Joyce’s invitation to collaborate and access to materials by Nanny Goat Productions.

Would you characterize the work that you were doing on Tits & Clits as political? If so, how?

I have been thinking about this a lot recently due to the intensifying issues around book banning in both school and public libraries. My archival work led me to become an archivist myself because I became interested in how archivists and librarians manage materials like Tits & Clits and how the kind of work that archivists do influences the scholarship that can be done in any arena.

Now, there is a big pushback against allegedly controversial or pornographic books and graphic materials, particularly comics. Maia Kobabe’s Gender Queer was the most banned book of 2021. In fact, a former Republican congressional candidate in Virginia attempted to get Gender Queer (as well as the novel A Court of Mist and Fury) legally defined as obscenity in 2022, in a way that would have punished both booksellers and libraries who made the book available to children. However, a judge threw out the lawsuit, ruling that it violated the First Amendment. Art Spiegelman’s Maus has also been censored in school settings, e.g., removed from an English curriculum. And of course, Alison Bechdel’s Fun Home has also been challenged in public and school libraries. There is now a reinvigorated surge of book banning and censorial activities that target comics, especially those with queer or sexual content.

The political aspect of my work is asserting that comics like Tits & Clits do have social value (to paraphrase obscenity law), that there is something important about what the women who created and contributed to Tits & Clits were trying to say, and why the graphic, explicit nature of T&C is not a justification to suppress the series. My research is part of a broader series of issues about what content is acceptable in discussions regarding sex and sexuality.

Additionally, with the ongoing backlash against women’s reproductive health options, my publishing on Tits & Clits is even more political. The original legal definition of obscenity prohibited not just information about sex and sexuality but also abortion and contraceptives themselves. We are in a similar period of efforts to tamp down sexually expressive work and factual information on or access to abortion.

Could you speak more on why a modern audience should care for information about abortion told narratively in Abortion Eve? Today, many can easily find details about the subject online.

In 1972, when Joyce and Lyn began working on Abortion Eve, abortion was not yet legal nationwide as the Supreme Court had not made its ruling in Roe v. Wade (1973). Nevertheless, within the narrow context of therapeutic abortion, the procedure was legal in California where Joyce and Lyn lived. Roe v. Wade would later provide more protection for abortion.

Abortion procedures have evolved since the early '70s. Abortion Eve outlines a D&C (dilation and curettage) abortion, which was the common method at the time. While D&C abortions are still performed, there are now various options, including abortion pills, or medication abortions.

Abortion Eve is valuable in a contemporary context because it illustrates not [just] the ongoing political and personal concerns around abortion, particularly related to people’s religious beliefs and issues with access. The procedure, especially pre-Roe, was expensive. The availability of abortion was influenced by how much money and time you had. This remains relevant.

So yes, some of the information about what abortion actually is that Lyn and Joyce were trying to share at the time is different now; people can find details elsewhere. But the context of the comic matters - in the early 1970s, different states had either decriminalized or legalized certain forms of abortion, but the procedure was not yet available to people nationwide.

Who was reading Tits & Clits or Abortion Eve?

It is difficult to know who was reading either comic. The only evidence regarding who was perusing them are receipts from orders, fan mail that Joyce and Lyn received, or hate mail.

When Lyn and Joyce published Abortion Eve, their goal was to create something distinct from Tits & Clits. It was intended as an educational comic, more akin to Facts o' Life Sex Education Funnies (1972), edited by Lora Fountain. The two tried to distribute Abortion Eve through “overground” channels. For example, Joyce wrote to the National Organization for Women to try and get them interested in the comic book and help distribute it to the members of the group. They also solicited clinics and worked at the Multi-Media Resources Center [MMRC] of Glide Memorial Church, aiming to place the comic in sex education spaces rather than underground distribution channels. It is not clear if their attempts were successful.

Although MMRC purchased a certain number of Abortion Eve copies, their final destination is unknown.

However, based on the fan mail of Abortion Eve, several health educators obtained the comic. Lyn and Joyce received a few letters from nurses, college students, and others involved with sex education and reproductive health. These people were generally positive, saying, “It is a helpful tool; it is engaging, particularly to young people, which we appreciate about the comic format.”

Based on reviews of the first issue of Tits & Clits, readers of underground newspapers like the Los Angeles Free Press or Screw magazine possibly perused the comic. So it was in the underground network. Additionally, emerging feminist newspapers at the time covered the comic in a way they wouldn't for later T&C issues.

The initial issues of Tits & Clits and Abortion Eve got the most traction from underground channels. Later in the decade, when the women of Nanny Goat returned to publishing in 1976, those underground channels were not as strong, leading them to explore distribution through the feminist press.

I was hoping for a simple “x = y” style of analysis, but, unfortunately, that does not seem to exist.

No.

I have one more thing to say about Abortion Eve: it was published in 1973, and Lyn and Joyce initially got some warm reviews of the comic, but then they encountered a spike of critical mail later in the decade. I do not know why this happened, although a couple of the incidents seem to be related to the fact that a public library had purchased copies of Abortion Eve and was displaying them. A few people found them at their library and were angry, particularly about the Alfred E. Neuman / Virgin Mary parody on the back cover and wrote these angry letters to Nanny Goat Productions. Even so, Joyce and Lyn did not get pushback from reader mail in 1973.

Whenever I email Ron Turner regarding the audience for Tits & Clits, he emphasizes how the inflation of the '70s restricted many consumers’ abilities to purchase comics en masse. Did the economic problems of the decade change the audience of Tits & Clits after the comic returned from its hiatus in 1976?

Inflation likely impacted the audience as printing costs increased in 1973, leading to smaller print runs for underground publishers. These prices never seemed to decrease again. Joyce and Lyn published the first issue of Tits & Clits in 1972 at the lowest production cost they would ever experience; the price went up from there.

Again, it is difficult to say exactly who the audience of T&C was. There are so many factors related to why the market shifted and declined. However, price certainly played a role in the changing audience (if that group did alter).

Nanny Goat Productions collaborated with Last Gasp later in the 1970s, partly due to the higher production costs. To offset these costs, they had to increase prices for individual issues of their series and initially print fewer copies. And, if you have to raise prices, you could suppress your former audience.

Did you find a difference between statements that you received in your interviews and what you found in the archives?

The biggest difference is dates. Many artists have a memory of something happening at a certain time, and archival materials will indicate how it occurred at a different date. But I found no major discrepancies…. It is hard to remember the exact details of what happened 50 years ago, even if you recall the broad contours.

Do you think that, after the reprint of Wimmen's, the quote-unquote collective is getting its due by scholars?

It is difficult to assess, but I think the reprint has helped. More scholarship has come out since 2010 or so, possibly beginning with Hillary Chute’s Graphic Women.

I want to note that Trina Robbins has been writing about women’s comics, not only with an “i” [Wimmen’s Comix] but also without an “i” [i.e., in general], for some time. Her first nonfiction book was released in the 1980s. So people have been interested in women-created comics for a long time. Going back to what you were saying about this repetition of people saying, “At last, comics are being recognized as valid!” A parallel trajectory with women in cartooning exists wherein many articles, going back to the 1970s, shout, “Finally, women are being recognized in this field! After a long time, they’re being taken seriously!” Scholars contemporaneous with both Wimmen’s Comix and Tits & Clits were writing about these productions, particularly in feminist publications. Graduate students would contact both Nanny Goat Productions and the women of Wimmen’s Comix. Therefore, academics have been trying to do this work for several decades. Nevertheless, these efforts are hard to access now. It is difficult to track down a master’s thesis from 1976.

How did writing about Tits & Clits and Wimmen’s change from the '70s to now?

The thing that shifts is the framing of how different scholars address these comics. One resource that I found at the Library of Congress [Women's Culture: The Renaissance of the Seventies, Gayle Kimball; Scarecrow Press] was primarily focused on Nanny Goat Productions, analyzing the impact of their work. Since this evaluation was published in 1981, Nanny Goat Productions was still releasing comics. So, in that instance, you are not talking about something that is over; rather, you are speaking about something that is ongoing, that is currently impacting the feminist movement or the field of cartooning.

Now, much of the writing about the two series is framed as, “These brave pioneers intervened; they set the stage; look at all these people who came after them.” You could not write something like that when you’re contemporaneous with those people. That is the major difference.

Mary Fleener observes how, by the '90s, a myriad of comics both by and for women had been released and, thus, did not have a big “splash” in the way that Wimmen’s or T&C had for the cartooning field.

With Tits & Clits α [the first issue], Lyn and Joyce were the first women to self-publish their own comic as far as many scholars have documented. (It’s quite possible that there are other comics we don’t know about or that were not attributed correctly. I can’t say if we are sure that they are first.) In many spheres of cultural production and other industries, being the first to do something is often celebrated, especially if you come from a historically marginalized group. And, then, eventually, the “firsts” stop coming, or shift to a different identity or breakthrough. What was initially notable simply for existing becomes more commonplace. While women’s-only comics anthologies are still being published, I don’t know that they quite have the same impact that they did initially as far as being “firsts” at this point.

It’s worth noting here too, as I described in my thesis, that individual cartoonists and other artists have varying reactions to being categorized and recognized in terms of their gender. (This is also true for other identities.) For some people, it feels liberating, for others, stifling.

Do you think that this new re-release of T&C is going to have similar effects to the Wimmen’s Comix re-release or not?

I would hope that it does. Previously, Tits & Clits was hard to find. The Alexander Street Press has licensed some of the content of the series and made it available through one of its databases. Also, various institutions hold copies of issues of the series. But back in 2011 and 2012, I found T&C more difficult to find than Wimmen’s Comix, possibly because fewer institutions collected it. At least, Schlesinger Library did not have copies.

Another reason why Wimmen’s Comix was more prominent in scholarship than Tits & Clits or Abortion Eve is due to Trina Robbins. She has played an important role in documenting women’s comics. Trina always mentioned Tits & Clits and the work of Lyn and Joyce, although she was not as directly involved with the series.

How did the ideology of Nanny Goat Productions compare with other comic creators, especially those contributing to Wimmen’s Comix?

Lyn and Joyce were much more stridently anti-censorship than some of their peers because of their experiences with the Fahrenheit 451 bust in 1973, which demonstrated to them how their work could be classified as legally obscene and the potential consequences for their business. This is not to say that other cartoonists did not also hold these views: notably, Robert Crumb had the most trouble of almost anyone with underground comix busts, and other artists who contributed to Zap Comix had problems too, so they were also fervently anti-censorship. Yet I think that Lyn and Joyce were more directly impacted by their brush with law enforcement than some of the other underground cartoonists whose works were also defined as legal obscenity in the 1960s, ‘70s, and ‘80s.

Most of the obscenity charges for underground comix impacted suppliers and booksellers, like the infamous bust of Zap Comix #4 at the East Side Bookstore in New York City in 1969. Often, at least to my understanding, obscenity charges are filed against publishers or distributors of material, rather than the creators of the material, though of course such charges have a chilling effect on creators. (It’s worth noting that, in 1994, Mike Diana became the only cartoonist who has been successfully prosecuted on obscenity charges for his zine Boiled Angel, though of course that was long after the underground comix scene ended and Nanny Goat Productions ceased operating.)

The Fahrenheit 451 bust that impacted Nanny Goat Productions occurred at the bookstore Lyn used to own in Laguna Beach. This proximity made the bust particularly personal, and the women of Nanny Goat believed they were the real targets of the arrest. A district attorney involved in the case noted, in the Laguna Beach Daily Pilot, how law enforcement was trying to get to the creators and publishers of underground comix, rather than the distributors and booksellers. For the women of Nanny Goat, since they (like Mike Diana) were the publishers, distributors, AND the creators of their material, they could have been directly charged with obscenity charges and wound up in a situation like Diana's, where they would have faced fines or even jail time for their work.

It’s worth noting that some of the other contributors to Tits & Clits and Wimmen’s Comix, notably Melinda Gebbie, also had their own brushes with obscenity law in the 1980s, particularly when their comix were imported to other countries. As I mentioned briefly in the introduction to Tits & Clits 1972-1987, Joyce went to testify in support of Gebbie’s comic Fresca Zizis (1977) and Knockabout Press in a UK court in 1985. However, the judge ultimately found the comic legally obscene and ordered the imported copies to be burned.

Nanny Goat Productions’ philosophy regarding legal obscenity also connects to larger divisions in the feminist movement about erotica versus pornography. In the early 1970s, those in the feminist movement argued about whether one should view depictions of sexuality as liberatory or repressive. This issue came to a head in the late ‘70s, especially with the rise of feminist organizations specifically focused on addressing pornography with violent, sexualized depictions of women. Certain feminists, like Catharine MacKinnon, suggested legislation which could target pornography as a form of sex discrimination, a civil rights violation. This was meant to be a way for feminists to get rid of porn without using obscenity law, which has its roots in efforts to suppress information about birth control and abortion, as well as contraceptives.

Lyn and Joyce vehemently disagreed with the anti-porn feminists at the time. The duo had personal experience in seeing how subjective classifying something as pornographic or obscene was, and how ruinous it could be to be targeted by law enforcement on obscenity charges. They sided with the nascent ideology of “sex-positive feminism”. Joyce has a one-page story in Tits & Clits #6 called “If Ya Can’t Join Em…” It includes a stereotypical depiction of a butch-looking woman protesting pornography. The woman goes into a porn store to buy research material and is turned on by it. The narrative represents the different vantage points on pornography versus erotica that were arising within the feminist movement at the time, and Joyce and Lyn’s sense that anti-pornography feminism would only have oppressive and censorial impacts because no one could really define pornography.

So you do not think that Joyce and Lyn would approve of the increasing number of "Hays Code advocates" on sites like Twitter and TikTok?

I think that Lyn and Joyce understood that efforts to tamp down on sexually explicit material often have as much to do with repressive politics as with sex itself. I’ll quote an undated essay by Lyn here: “Without sex there would be no censor, and with sex the censorship is often directed towards women.” Today, as you and I discussed earlier, a lot of efforts to censor or ban comics and other books have to do with gender, sexuality, and race, which have long been hot topics for conservative ideological suppression. Censorship that allegedly targets depictions of sex badly conceals concerted efforts to block discussion of different identities and experiences and to deny that human difference exists and has always existed. It functions to make human experience impermissible in public discourse. The women of Nanny Goat were trying to achieve the opposite effect: they wanted to break down taboos and deconstruct myths about female sexuality to assert that women were human.