When I heard Peter Milligan was going to attend the Comic-Salon Erlangen, I knew I had to go. Since the mid-1990s, Milligan’s writing on titles like Human Target, the psychological study of a bodyguard who impersonates clients targeted for assassination, and X-Statix, an absurdist media satire starring a group of celebrity superheroes, had left an impression on me. For all its self-aware genre thrills, wry wit, and frequently inconclusive struggles with concerns of identity and memory, Milligan’s work has been moored by a heartfelt humanist outlook that belies its more sardonic surface trappings.

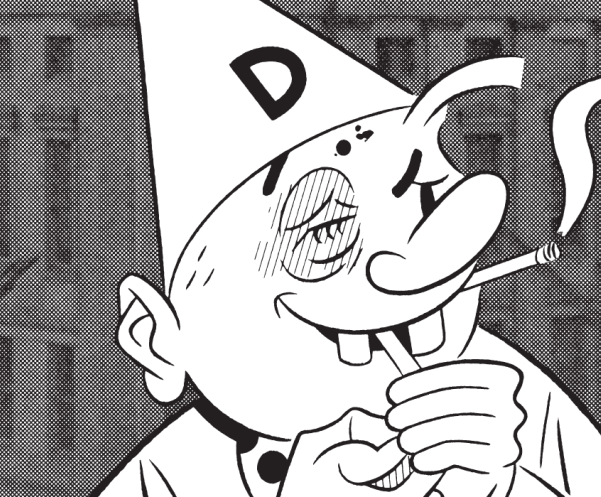

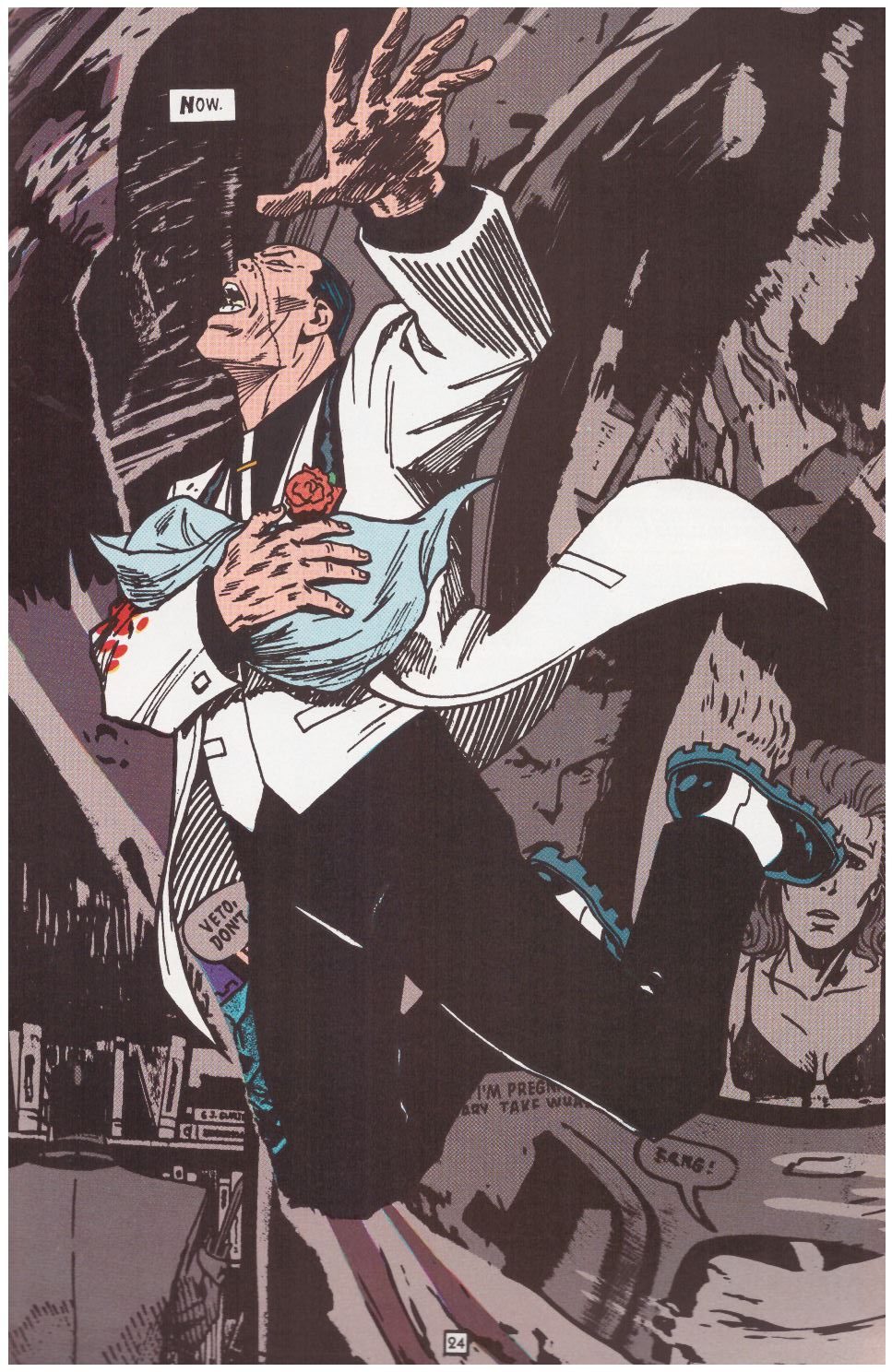

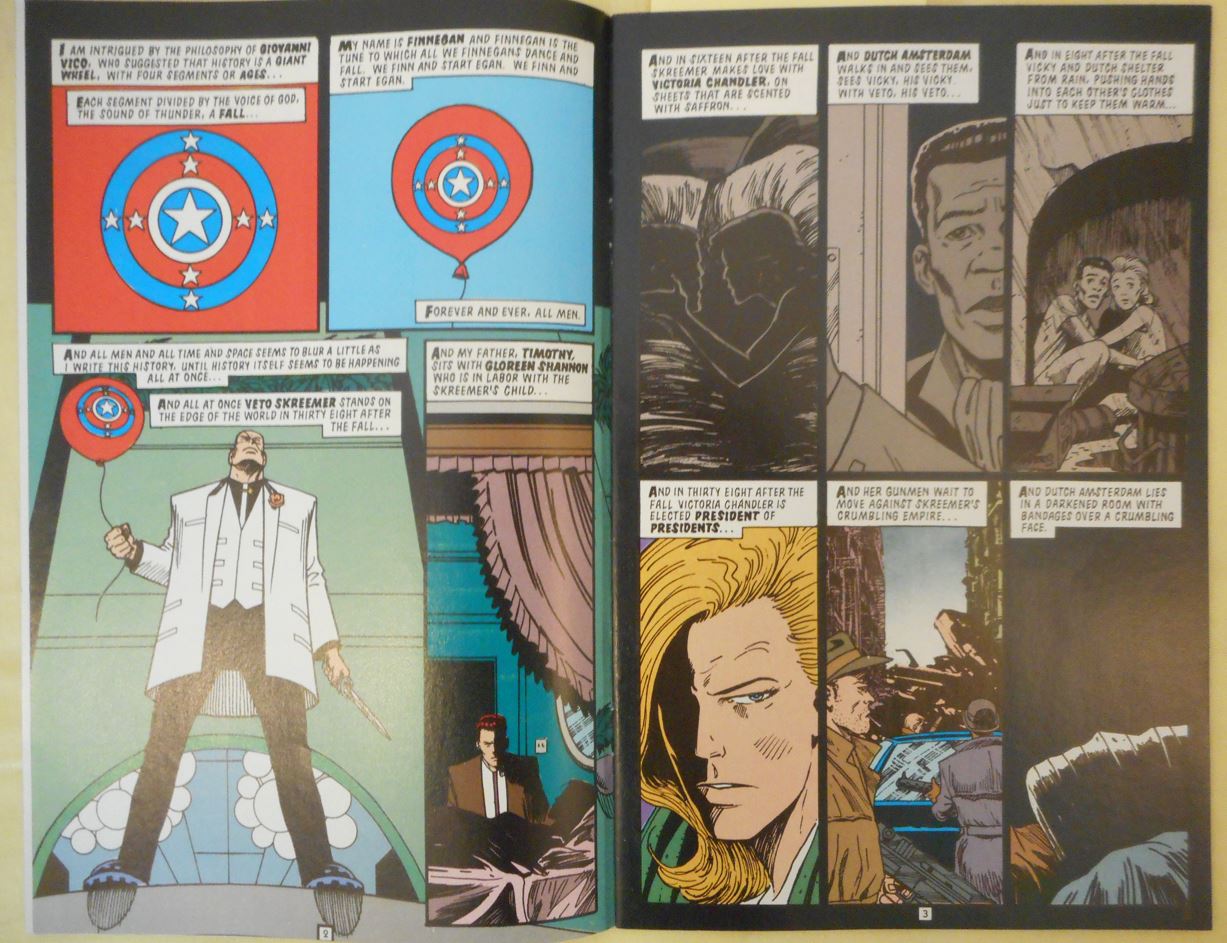

Based in London, Milligan began writing comics more than 40 years ago. Following The Electric Hoax, a strip created for Sounds magazine with Brendan McCarthy in 1978, and “The Man Who Was Too Clever”, the first of many 2000 AD contributions, drawn by Brett Ewins and published as one of "Tharg's Future Shocks" in 1981, Milligan’s work soon appeared in the U.S. anthologies Vanguard Illustrated and Strange Days. With the miniseries Skreemer, created with Ewins in 1989, and the subsequent relaunch of Shade, the Changing Man in 1990, Milligan emerged as one of the most prominent British voices in American comics, racking up brief runs on Animal Man, Batman, and Detective Comics, all published by DC Comics. In 1993, he was among the first creators to be published by Karen Berger’s and Art Young’s Vertigo imprint at DC, contributing titles such as Enigma, The Extremist, Egypt, Girl, and many more over the following two decades.

Milligan has since collaborated with scores of artists on hundreds of comics, released by a wide range of publishers both in Britain and in the U.S., in addition to writing screenplays for film and animation. So when we sat down over beers on a hot but breezy late afternoon in June at a café in one of Erlangen’s tranquil church squares, there was no shortage of things to discuss.

I’m indebted to Nick Hasted, whose talks with Milligan in 1997 (first published in The Comics Journal #206, August 1998) were a crucial source of insight and informed my line of questioning. And I’m grateful to Jörg Faßbender, translator of a recent German edition of Enigma, for his help arranging this interview.

-Marc-Oliver Frisch

MARC-OLIVER FRISCH: I’d like to start with something not directly comics-related, the 2000 film Pilgrim that you wrote the screenplay for, directed by Harley Cokeliss and starring Ray Liotta--

PETER MILLIGAN: The late Ray Liotta.

The late Ray Liotta. He died--

Really recently.

About three weeks ago, as we’re speaking.

That was really sad.

How did you get involved in this film?

Harley Cokeliss, the director, was interested in comics, and he contacted us. And I was quite interested in this idea of a man who is continuously discovering things about himself and almost feels like a blank slate - but of course no one’s a blank slate. So this is the story of how the story developed. I have to say, though, some changes were made at the end which I think took out what might be called some more Peter Milligan touches to it, some changes beyond my power, that I think normalized it a bit. I had some elements in it that were perhaps more reminiscent of the kind of work I do in comic books, and I think, as often is the way in films, without me even knowing there were some last-minute changes when I left. I spent some time in Mexico as it was being shot, which was very cool, meeting Ray. Overall, there were some interesting things in the film, but I think it could have been more interesting. But that’s always the way. You look back at some work and you wish you had a little time machine to go back and change this or add that, so I think that’s quite normal.

It struck me as a very Peter Milligan story.

Well, I think the high concept is a very Peter Milligan story, because quite a lot of my work has been about identity. And I think the story of Pilgrim was completely about identity. Even the name "Pilgrim" suggests someone who is on a road to some kind of discovery - either a religious kind of discovery or a self-discovery. So I think that was the deal with that. In its big ideas the story was very much me. But I think some of the ways in which the ideas were realized were perhaps changed and perhaps normalized a bit. They took out some of the slightly more idiosyncratic touches of the original screenplay.

Right. It seems like a very noir-ish film--

Deliberately so.

But compared to other noir-ish films the ending is almost a happy ending.

Exactly. Exactly, yeah.

So that’s what they changed?

Yeah, and I think when I deal with Americans, often I find there is a difference in feel. Perhaps it’s a very British thing or a more European thing. I’m often looking for the darkness in the ending, and I think the Americans are often looking for the brightness in the ending. But you know, the greatest stories ever told, one could argue, are the Greek dramas—Euripides, Aristophanes—and they did not worry about a happy ending. I mean, a happy ending was the furthest thing on their mind. That was not the issue. You have to be a grown-up and deal with it, it is life. But, you know, Americans-- and a lot of my best friends are Americans, and I think they’re fantastic, but... they want to be happy. They want to be made to feel everything’s okay. And it’s not. It’s just not.

Was the script written with Liotta in mind?

No, it wasn’t. The script was written, and then when Ray came aboard... were some changes made? Yeah, I think when we met up and Ray had a couple of scenes, he said "can we kind of tweak this a little bit," and then I spoke to him and I think we changed a few things. But nothing major. It was nothing that was fundamentally changing the script. So I think it was essentially the script that I had written except for the changes that were made later on without my knowledge. But again, that’s quite normal. As soon as you do something like a screenplay or even a comic book, it’s a collaborative medium. There’s other people involved and other people have their ideas of how it should be. So if you hate that, don’t do it, if you know what I mean.

I don’t know if you knew, but Liotta was an adoptee and reportedly hired a private investigator in the late 1990s to locate his birth mother. So this seems like a role that was tailor-made for him.

Different people have different reasons for wanting to take a film on. On another film I wrote, called An Angel for May, which was set in Yorkshire, Tom Wilkinson, who is a fantastic British actor, said one of the reasons why he did it was—I would like to have thought that he thought the screenplay was so fantastic—but actually there was something in it that reminded him of his childhood. And a comic book of mine is on the way of being made as a film, and I can’t say what it is, or who it is, but a very well-known British actor is going to be in it, and the reason why he wants to be in there is, when he was young, a teenager, he loved this comic. And he said, "let’s try to do something a little bit different," and this comic landed on his desk, and just by coincidence, he said, "oh my god, it’s this." So then we had meetings with him, and I can’t tell who, but he’s a really well-known actor. And it was great talking to him, because he loved the comic already. We didn’t have to sell the comic at all. It was just about how best to realize this comic in a different medium. So often I think that’s what happens when an actor sees something in a script which perhaps reminds them of themselves. And I imagine this is what you‘d want, isn’t it? You’d want to think this story might be set in ancient Rome, or this story might be set on a different planet, but at its heart, what this character is going through resonates with me.

You mentioned going to Mexico and meeting Liotta--

I didn’t just meet him, we hung out.

How closely were you involved while the film was being shot?

Well, at one point we were shooting a scene on the beach, and we needed a rewrite, and I was walking back to my van, scribbling the script-- I was rewriting the script as I was walking on the beach to my writer’s office, and the director said, "Pete, hurry up, we gotta do this." And I said, I’m rewriting the script as I walk across the beach to my office. I think this is quick, you know. It doesn’t get any quicker. So there are a few things I changed then and there. And you know what? It was great fun. I mean, shooting a film in a small town in Mexico with Ray Liotta, and of course all of the town knew we were making a film-- I mean, it’s not like we were stars, I’m not into that kind of bullshit, but everyone was kind of aware, and some of the people from the town were employed, not only catering but in the office as well, and there were some really interesting experiences. It was a real eye-opener. In this town there were some retired Americans. I don’t think their pension went further than Mexico, and they went there to slowly drink themselves to death. And I think they could do it in a better fashion than they could have in America because the dollar was stronger there.

There’s this quote from Skreemer: “Sometimes the past seems too big for the present to hold.” That’s something that struck me about a lot of your work, this sense that the past is almost kind of attacking the present--

Well, I’ve been struck by this notion that the present is this pinprick of nowness, and we carry this huge expanse of the past. Which is obviously gone, but is this huge thing, and it... I don’t know how deep it is, but that’s always struck me. And with Skreemer obviously it was really a key element. It was also ironic, because normally the only thing that exists is now, whereas the future hasn’t happened yet and the past is gone and subject to memory and the only thing that exists is the present. Obviously with Skreemer it was very different, because he could see into the future. He could see what was going to come in his life, so his relationship with the past and the present and the future was different from that of most normal humans. Yeah, I’m not sure I’ve answered your question. Have I?

There are many answers to that question.

Yeah, there’s no answer. It’s just something that’s intrigued me. How we walk around in this ongoing present which continuously exists as a pinprick and we all have this huge past behind us.

Let’s circle back to your talks with the Journal’s Nick Hasted in 1997 that you mentioned earlier. Do you remember those?

Well, I don’t remember the talks.

Back then, you said, “Our idea of the past, our idea of the future, is actually a structure that we use, because it’s the only way we can look at things, it doesn’t exist. It’s a structure; it’s a fabrication; it’s not the reality. That’s quite daunting, as well, the idea that what we know as reality does not exist. It’s a model we use to try to describe something that defies description.”

Right, now that is a good answer. It’s much better. You’re not going to get anything like that today. It’s too hot! [Laughs] Well, yeah, but it’s true. Because the past doesn’t exist. It can be recorded, it can be remembered, but memory is faulty, and anyway, memories die out. And so the past doesn’t exist anymore except in the imprint it’s had on you, the effect it’s had on you. And the future certainly doesn’t exist, and is improbable. And the only thing that exists is this tiny pinprick of reality, this is the only thing we can know. And it’s always struck me how we are continually teetering on this tiny piece of reality whilst flanked either side by the past that is gone.

This reminds me of this Spiegelman quote [from “Memory Hole,” in the 2008 edition of Breakdowns], that “comics are time, time turned into space.” As part of this model that we use to look at time, would you say comics can be a means to help us grasp this concept?

I think all forms of storytelling actually are a kind of wrestling with the past, a kind of wrestling with this stuff that’s gone on before us. And I think that comics, films, novels - I think that time is key to all of that, and I think that comic books have a certain relationship to time which is different from novels or different from films, and that’s why certain stories work really well in certain mediums and some don’t. I’ve always thought that horror stories don’t work as well in comics as they do in novels or in films, and I think that’s about the control of time and what is revealed. What’s scariest in a film is that we do not control time, it’s that time is spooling in front of us and what’s gonna happen is gonna happen and we have no control. In a novel you have control over time, because it depends on how fast you read, and you can stop reading, but the great thing about a novel is that so much is not revealed, and so much is inside your head. And in this sense you have less control over your imagination, less control over the film that’s running inside your head. In comics, you have neither of that, because the reader decides how quickly they turn the page. But also, it’s sort of all out there. So it’s more definite in terms of what’s going on.

Comics is also quite different from film, or from animation, in terms of dialogue, I imagine - how do you approach switching between these modes?

At heart, I don’t. At heart, you still got to understand where someone’s coming from. You still got to understand the character. I mean, there’s tiny little structural things, like in a comic book you might be thinking in terms of panels, in terms of balloons, in terms of page turns. But at heart it’s the same for me, because I think that I want to understand what the character’s about, I want to understand what the scene’s about, and those principles are the same whether it’s a screenplay or a comic book. Characters move around through time and space with an object.

How much of your workload is related to comics these days?

Well, quite a lot. I mean, I’m really enjoying what I’m doing at the moment, which is working for these smaller independent companies. Because I tend to have lots of ideas, and doing five- or six-episode short miniseries is a good way to get lots of ideas out, and it isn’t like you got to do a, say, 24-episode thing or something. And these smaller companies are very interested in what you have to say. AfterShock I really enjoy working with, I think they’re a really good company.1 AWA, which is Axel Alonso’s new company in New York, it’s a really good company.

At some of these publishers you’re working with editors that you were working with back at Vertigo, is this something that--

Well, not Mike Marts [editor-in-chief for AfterShock at the time of the interview], because he was at DC. I think I may have done a Batman story with Mike, but I certainly knew him at DC, so we had a kind of relationship.

He also was at Marvel when you did X-Men, I think.

I forget, but he probably was - I know that we had worked together. And obviously Axel Alonso and I worked together. So yeah, I guess that’s how it works. I know people, so it’s easier for me to discuss with them ideas that I have. Of course, you know, if you like working with each other. I mean, it seems to me that’s one of the critical things about deciding whether you want to do a comic for a company - it’s whether or not you enjoy working with the people there.

When people have asked you about your favorite work, you’ve said you remember the time you spent working on certain projects and the people you worked with, and that you don’t really have any favorites other than that. Would you say, in a sense, that the process itself and the relationships are what really matters?

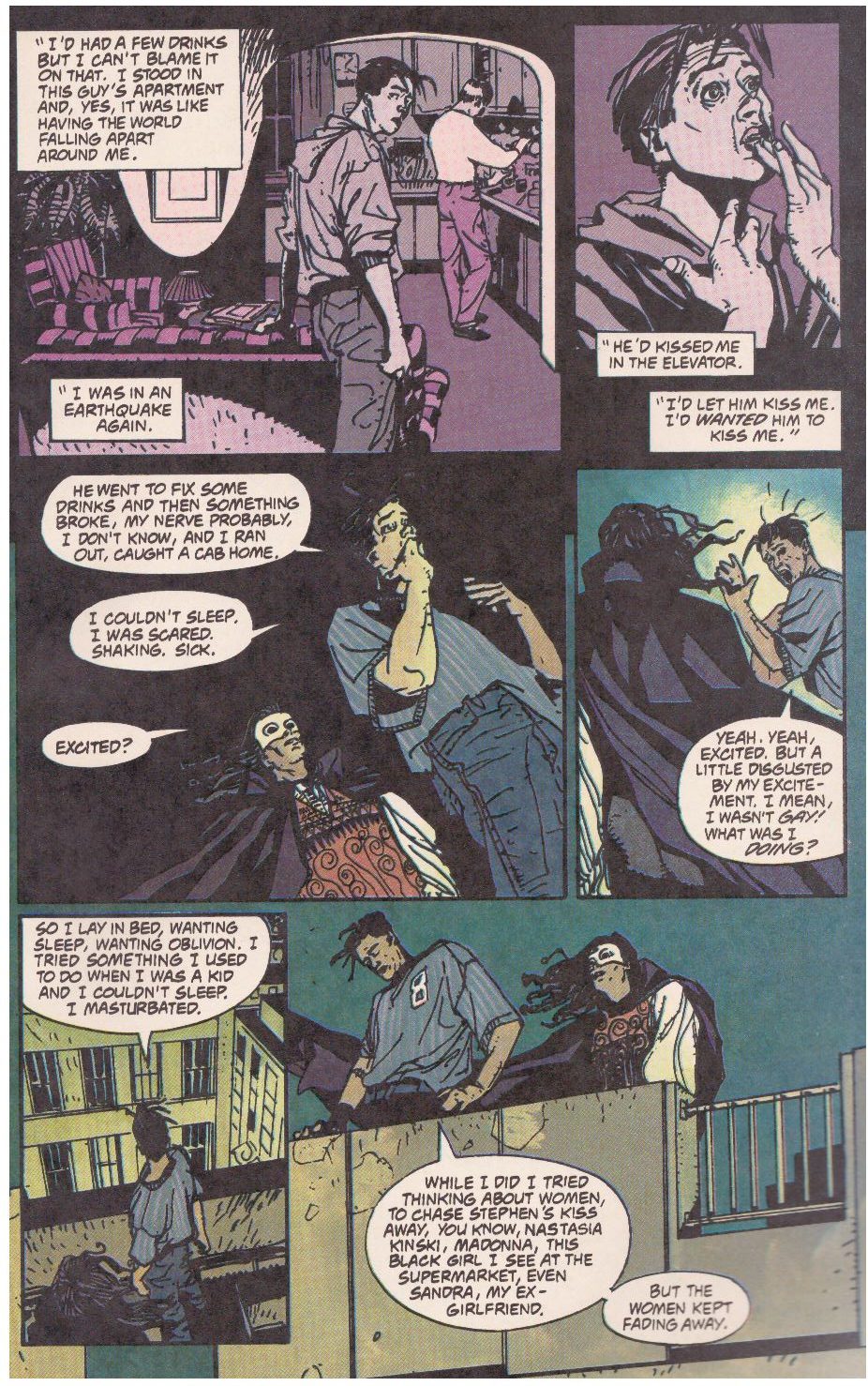

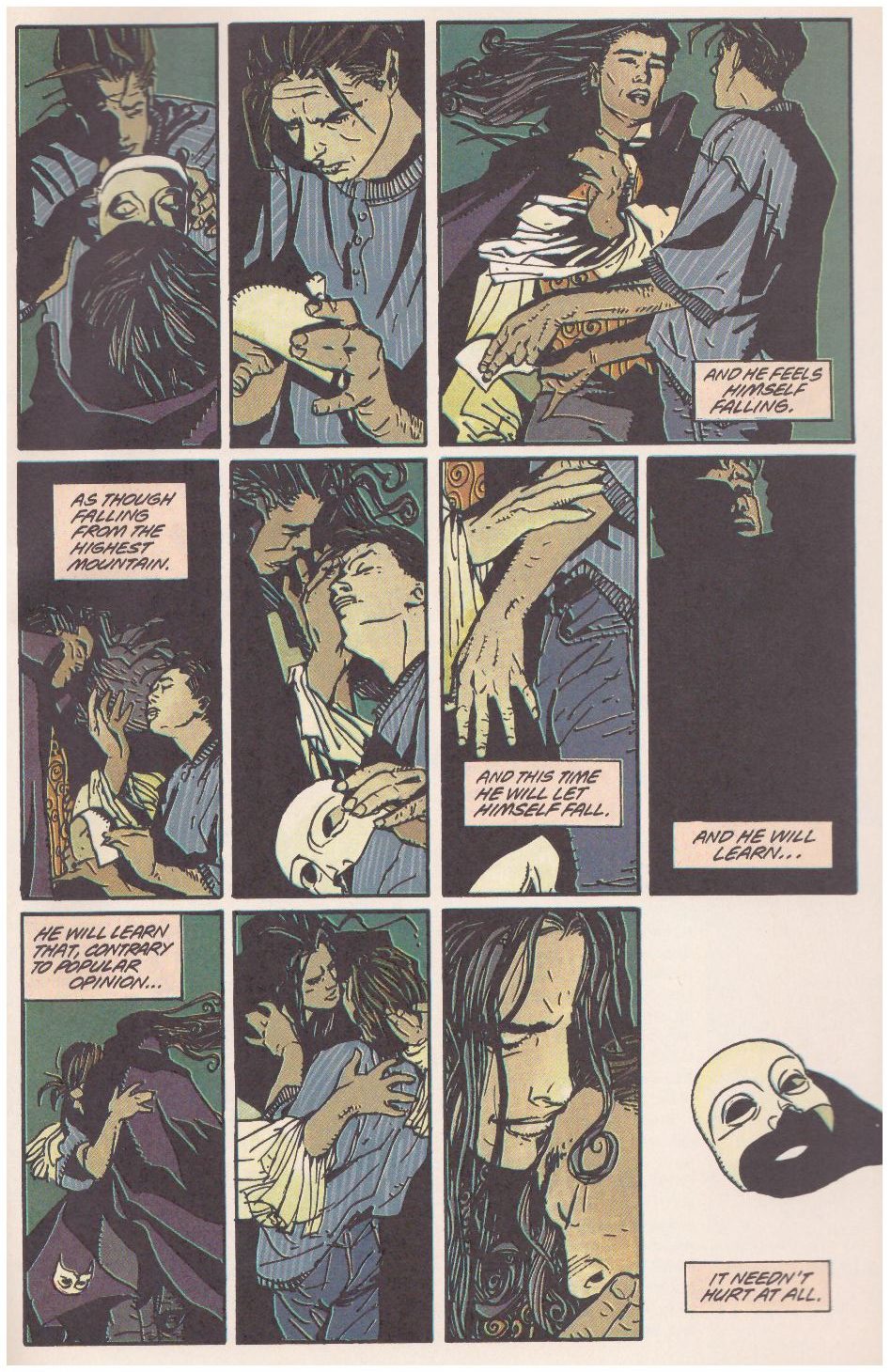

Well, clearly it’s not all that matters. It’s not like it’s an ongoing party. It’s just that when you look back at the time when you were writing, some of that is-- and I don’t just mean I was having a great time, it could also be a really good creative time, one that feels like you’re writing something important, something that felt important to myself. Shade, the Changing Man was fantastic. It seemed to have an attitude, and it seemed that people really connected with it. Enigma was an incredibly important book for me. It’s wrapped up in a close friend, who was the editor, who was coming out at the time. And some of my interest in Enigma, and I guess some of the inspiration for some of the things that were in Enigma, came through looking at my friend, who was coming out quite late in life - the editor, Art Young, he won’t mind me saying he’s gay, because he is. And what I detected was that... a lot of people use that word, “normal,” which is a very loaded word, because what is “normal”? And what struck me was that, as Art came out, he became, for what he was meant to be, completely “normalized” - not in a way that people who normally use the word “normal” in that context would agree was “normal”, but he just felt much more right for the person he was meant to be when he embraced his sexuality. So that was a really important bit for me when I was writing Enigma.

I used to always talk to Art about his experiences, which were very useful. He took me to some gay bars in West Hollywood, and that was just interesting, as a straight person, to go into gay bars. Not done coldly, as a kind of research thing - it was just me and my friend who was going through it. And at the time when I wrote it there was quite a lot of debate whether or not homosexuality—well, I’m no expert, I didn’t write it as an expert, I wrote it as an emotional response or something—whether or not it was “natural”, whether it was “nature” or “nurture”, whether it was something you were when you were born, or whether it was life experiences. And I suppose the conclusion I came to as a person, through looking at Art.... At the end, Michael [the protagonist of Enigma] wasn’t sure whether Enigma [the title character of the series] had made him gay purely so that he could have some kind of emotional connection with someone. But by the end, it didn’t matter. If Michael said, like it was with my friend Art, that it was the completely right thing to be, then it hardly mattered if he was gay because he was born that way or if it was because something happened to him. It has always seemed to me that was irrelevant, and what’s relevant was whether he was the right person in the right place at the right time, and not whether it was seen as an equally valid thing to be - which for him it clearly was. I don’t know whether this was PC or not, I didn’t really care about that. It was, as I said, my own emotional response to it - as a straight man, so obviously there’s always gonna be some things I can’t do. But one tries, you know.

So when you talked to Art—who was the editor, after all—about Enigma, did that change the ending?

No, no. No, I think it was what I’d always had in mind. But I think that if he’d felt deeply offended by it, I think I would have listened. Because he was gay.

I’d like to go a bit further back now. You’ve mentioned that you were basically self-taught when it came to writing.

Yeah.

I was wondering if you had any mentors, any people you could--

I wish. No, I had no mentors. I was my own mentor. And I led myself astray sometimes. But I was my own mentor. But you accept mentors, it’s like the people you read, you know. But actually I didn’t read comics when I grew up, it wasn’t really a wild thing I was into. I was just into art and literature, my great loves.

So once you got into comics and started writing Future Shocks strips for 2000 AD, was there someone who kind of gave you a rough--

Well, I mean, I was looking at some of the artwork that Brett Ewins and Brendan McCarthy were doing on some of these strips. But, really, I’ve never felt encumbered by what comics were meant to do, or how they were meant to be - because I didn’t really grow up reading them. I kind of made up my own idea of what comics could be. And even now when I write a comic, I don’t see it completely as a comic, I see it as situations, as people, so it’s always something of a surprise when I look at the finished comic. It exists in some kind of more rarefied place.

Is there a scene of creative people that you’re currently part of, or that you’re exchanging notes with?

Nooo, completely not. They do exist, I’m sure, but I’m not a member of any of them. I used to hang out more with Brendan and Brett, and we talked ideas - that was the closest thing, but they were friends. They were mates, you know.

Your output is impressive, you’ve been very prolific--

I like to keep busy. I mean, the trick with hard work is to only do things that really interest you, and then it doesn’t feel like work at all. It’s the best. To paraphrase Noël Coward, fun is not half as much fun as work. Because if work is fun, it’s the best thing you could do. You never wake up in the morning thinking, “Oh my god, I’ve got to do this.” As long as you try to handle it so that you’re doing things that really interest you, then it’s all good.

What does a typical day look like for you?

On a typical day, I get up at half past six, I’ll probably be at my desk at quarter-seven, then I have coffee and work through to nine o’clock and have breakfast. Then I work through to one o’clock and have lunch. You know, it’s very boring, but this is how it works. The morning is my most creative time. I really like the early morning. It’s quiet outside, and there’s not too many e-mails happening, there’s no phone calls happening. I don’t know if this is true or not, but I just find that at this early morning time, there’s still some kind of-- on some level, some kind of connection with the sleeping brain. Which, I hope, has some kind of creative flux going on, you know, mixed up with dreams, and the unfettered nature of the sleeping brain - perhaps unfettered by your own prejudices, unfettered by your own limitations, and it’s just your subconscious at work. I like to think that, by starting early in the morning, before I’ve done other things-- I don’t want to be talking to other people an awful lot, I don’t listen to the radio, but go straight to work, to have this link to the creative potential of the sleeping brain. That’s the idea, anyway. Whether or not it’s true - it might not be. But that’s how I feel, and for whatever reason the morning is my best time.

There’s a lot of logistical stuff to do, as well, in your profession, like pitching, communication with editors and artists, promotion, not to mention the usual chores and paperwork for taxes and such - basically, how do you get anything done, I guess is my question.

By working. I mean, there’s no shortcut. You have to do the work. And you have to work. I mean, you can’t just sit around being creative. Yes, you have to be at least sometimes, but-- in some ways I’m never not working... a bit. I rarely don’t have a notebook with me. If I’m on holiday with my wife, I grab hold of my notebook and I’m being a sort of a pain in the ass. It’s just that, you know, it means that you’re trying to think of ideas, you’re trying to think of scenes, so when you sit down to pitch some ideas to someone, rarely do I then think, “Okay, blank sheet of paper, what idea do I want?” Normally I’ve already been thinking about something. Maybe it’s half-formed, and maybe it’s just the germ of an idea that I’ve already been having, and maybe it’s been working its way through my brain and maybe some connection with something else that’s happened. So it’s a full body-and-mind immersion, you know. But that’s great, and that’s how I like it.

Do you write full-script?

Do I write full-script? Meaning descriptions, dialogue...? Yeah, everything. I think that’s the job. That is my job. Also, I think that turn of the page in comic books is a technically very important thing - at what point of a scene does the page end? It seems to be that comic books have certain things, and one of the things which are specific about comic books is that they come to an end of the page. And I think that does affect the reading of a scene, or the break of a scene. And dealing with this is part of your armory, these are things you just have to be aware of when you write comic books.

Comic books can do some stories. And now the next question, of course, is what stories, and I’m not sure what. But I have a feeling which irritates me sometimes, that comic books seem to be this poor cousin to films or TV. If you take away the money, if you take away the fame, and you take away all of that stuff, on purely aesthetic grounds, on purely creative grounds, they are of equal worth. And some stories are best told as comics, and the best way for them to be realized is through a comic. And maybe a film could be great, and maybe a TV show could be great, but some stories lend themselves really well to the comics form, because comics do certain things differently. At heart, you have words and pictures on pages that turn, and this is really unlike anything else. And it seems to be a really old way of telling stories. I’m not suggesting it goes all the way back to the caves - but I kind of am suggesting that. You know, it’s this basic thing of making pictures in a line, in a narrative, that really seems to be something that’s embedded in our psyche, our—if you like—archetypal human experience. And so it seems to be it’s at the heart of something.

So it’s irritating that comic books are increasingly just seen as some kind of feeder club-- I don’t know if you know the expression. In, say, football, and I think also in baseball, a big team might finance a small team, and really that small team is usually young players coming through in that team, and then the bigger team will say, "all right, let’s have them, and let’s elevate that person to the bigger league." So a feeder club in comics is that comics is just seen as, can this be turned into good TV? Can this be turned into a good film? And that is the way in which we value whether or not it’s a good comic. But, you know - if that’s what you want to do, fantastic. Great. But there’s other ways of judging whether a comic is good. And I think that’s whether it’s a story that’s best told as a comic. Anyway, that’s my little thing.

I’m really interested in the process here. Because there’s this so-called “Marvel method”, where someone gives the artist a rough description and then goes back and fills in the dialogue when the art is done. So you’re not doing this.

The truth is, there’s a bit of that in everything. I will do a full script. You know, Scene One, we see this, Panel One, we see this. And sometimes with references, and a caption, if there’s a caption, with dialogue. Scene Two... you know. So it’s a beat-for-beat. And I showed a comic book script—I was doing some comics work for Hammer, the people who are usually known for movies—and I showed them a comics script. They’d never actually seen one before, and the producer there said that it was kind of more like a shooting script, a shot-by-shot script rather than a regular screenplay. I thought that was quite an interesting insight. I guess that’s what my comic book scripts are like. Every single shot is laid out.

Now with good artists, they take that, and because they have the visual capacity, they might play with that a little bit, they might change that a little bit. And, as far as I’m concerned, as long as they’ve seen and understood the script and their change is a better way of telling that scene, I think that’s fantastic, and I’m always happy for that to happen. Then, once the artwork has been done—this is getting quite technical—and it’s lettered.... Well actually, before it’s lettered. Once the artwork has been done, I like to look at the artwork with my script, because sometimes scenes look different than you imagined them, or the way the artist has done it has changed certain things, so you do then have to tweak bits of your dialogue. It’s a constant state. It’s not like I do my job and then it’s over and then the artist does their job. It’s a constant state of, I take like five steps forward, and then the artist takes that a few steps, then I might take it another half-step forward. So it’s a constant kind of refining and changing. But I like there’s that side to it. It seems to me it’s specifically comics, and it seems to me it’s very interesting. I like getting the first artwork through and then saying: Okay, is this not how I imagined it? Or is this not how I described it? So then it’s a problem we have to solve. And I think that’s good.

How involved are you in the selection of the artists?

Well, I’m doing a story at the moment, and we’re in the process of choosing artists. So I’ve written the first script, which is good so that we can show it to different artists. And then the editor—we talked about the kind of artists we might need—sent me a list of five or six people he thought might be the right kind of ballpark, and then I look through them. And then probably I’ll say that these two look really interesting. And then the editor might say, "I really think this is the best one." And I say fine. And then we just ask if they’re free and then, depending on how big they are, you’re going to ask for a character design to see whether they’re right for the job. Obviously, if you’ve got-- I don’t know, if you’ve got Bill Sienkiewicz to do something, you don’t ask him for a character design, because you just know he’s gonna do it. And if someone’s of big enough stature, you’re happy to have them. But with people who are just starting out, you might want to look at a couple of character designs to see whether or not they’ve got the right feel for the story. So yes, I’d say I was very involved in the choosing of the artist. As it should be. But sometimes it’s just, you’ve got the story, and then the editor would say, "I think we can get this person to do it, they’d be great for it," and you just say yes.

You mentioned the irritating tendency to see comics as a feeder club for the supposedly bigger league of movies and television. In your experience, is this something comics creators are pushing for themselves, or is there pressure from publishers to regard any potential comics projects in that light?

I think it’s a bit of both. Bland answer, but true. It’s being pushed by publishers and I think some creators.

I wanted to talk about one of your recent books at Aftershock--

Good, I’m glad we’re talking about some recent books.

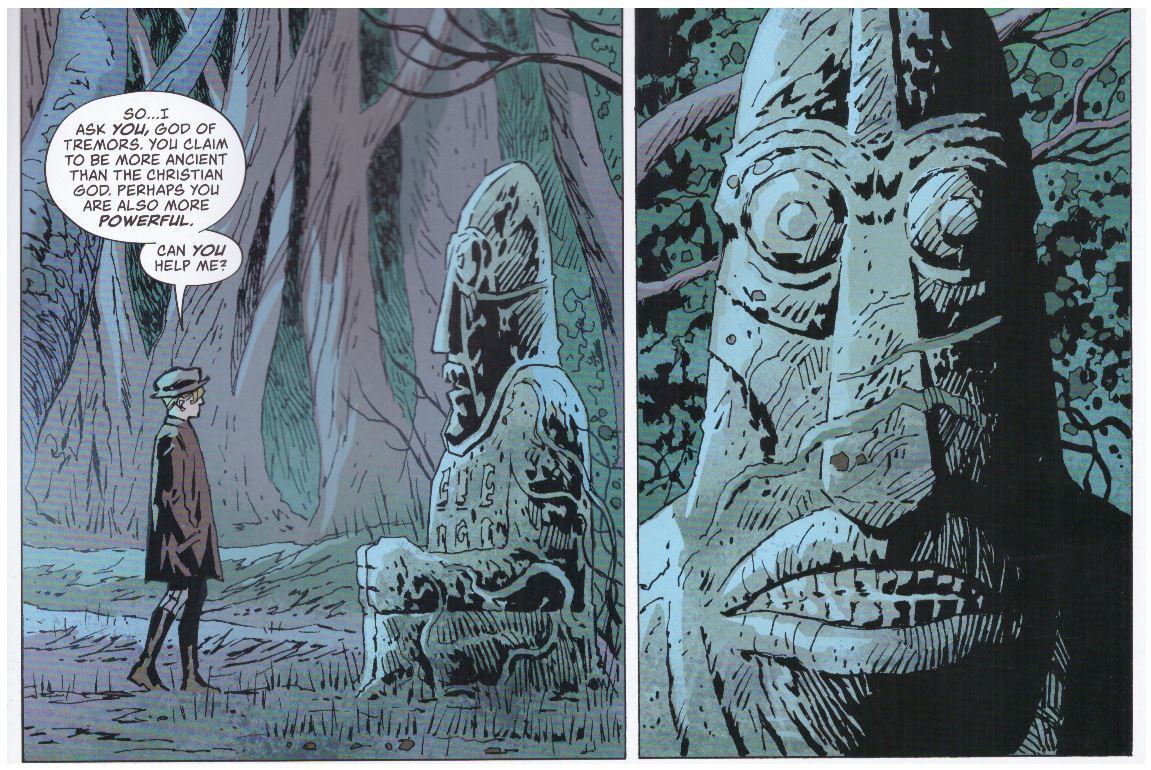

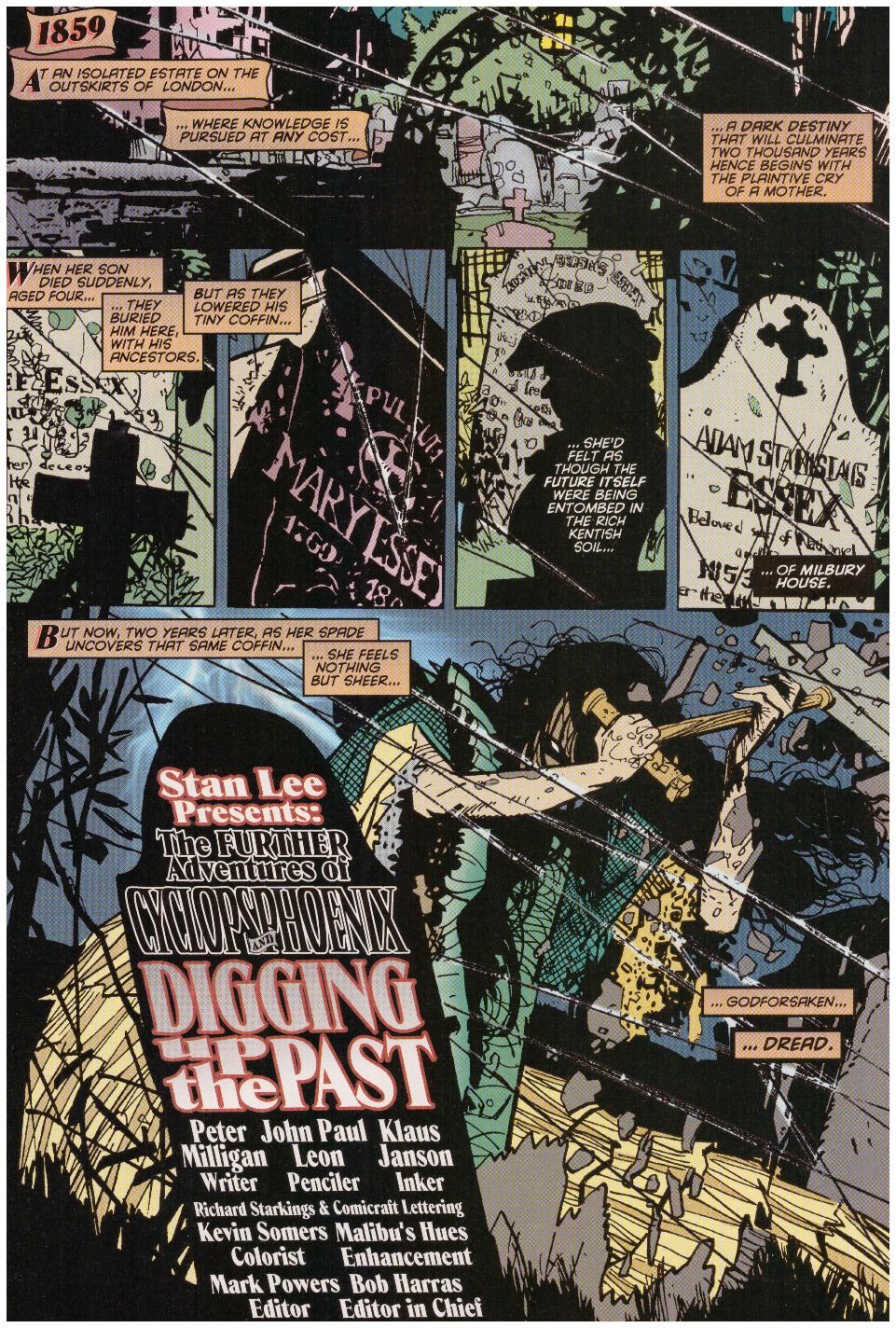

When you did God of Tremors, when the idea occurred to you, was it that you wanted to do a story about epilepsy, or was there another image, or aspect--

Yes. I’m epileptic, and I wanted to do a story about epilepsy. I had this idea of the God of Tremors, this idea of this young kid with epilepsy, and my first thoughts were of finding some kind of effigy, or finding some kind of thing which represented, if you like, the cruel power, or the damaged god that was epilepsy - which made him what he was, but also fucked up his life. So it was very cruel. And it was an idea which I had knocking around in the back of my head but couldn’t quite realize fully for a while, and then a couple of years ago I had a few bad seizures quite close together. I mean, normally my seizures are really well-controlled. Normally there’s a reason for them to happen. And it was during this time of having these seizures and recovering in-between and then feeling a bit patched-up about it, that the story came more into focus. Sometimes it’s about seeing the story differently and perhaps setting it in a certain time which allows you to explore certain aspects of the story.

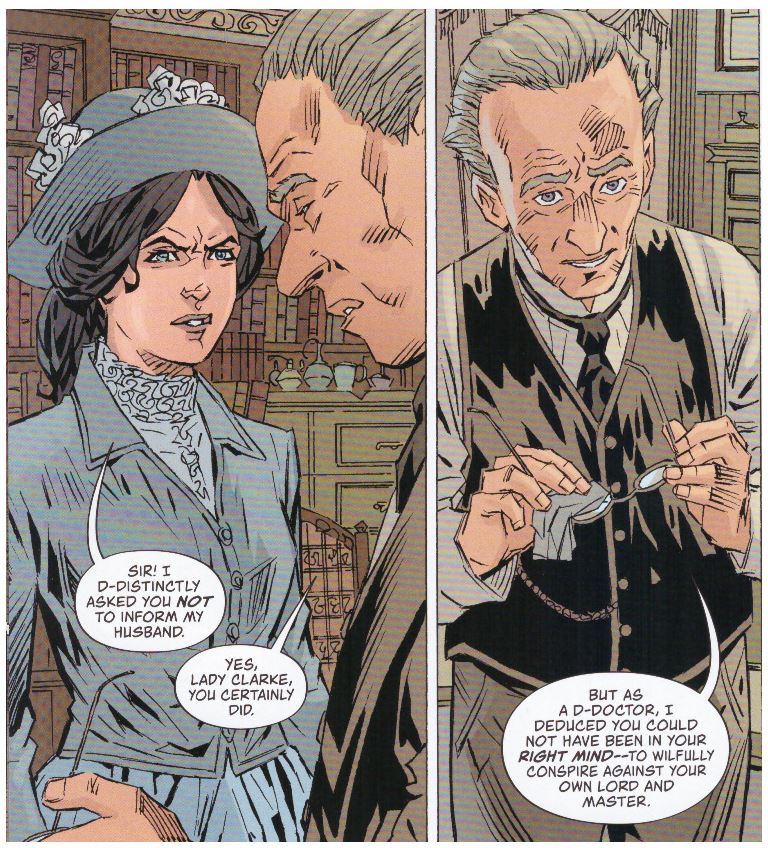

I mean, epilepsy obviously has been happening since there were people walking around, but in the Victorian era it was thought that because epilepsy in teenage years affects boys more than girls—not exclusively, but that was the idea, anyway—that epilepsy was linked to what the Victorians would call “beastliness”. Which obviously was masturbation. So Victorian morality was linked up with this medical thing, which I think is not the last time we see the morality of a time being mixed up with what is a medical issue. It happened with AIDS, I think it got all confused with morals and morality. Obviously, it’s got nothing to do with morals and morality. [A bell starts chiming in the distance.] So I think that’s quite a common thing that humans do, what societies do. And I knew that some kids who’d started to have epilepsy, they’d be sent to bed with their hands tied behind their back, so they couldn’t “abuse” themselves. How particularly cruel that was, to have this kid, who was obviously confused and scared by this terrible thing that’s happening to him, and not only that, he’d have to go to bed with his hands tied behind his back. That image struck me. It helped me to have the rest of the story fall into place. With that I realized I wanted it to be set in the Victorian era, so I could use that scene, use that moment, and sort of get a feel for what kind of story it was. [A bell starts chiming nearby.] I felt I wanted to set it in the history of British folk horror. In terms of films, there’s The Wicker Man-- I don’t know if you’ve seen it, it’s an amazing film. Look, honestly, you should see it, if you’ve got any interest in horror movies. It’s quite odd, but it really holds up. It’s part of a line, if you like, of British folk horror, going back to M. R. James, who was a classic writer of ghost and demonic stories and, ah-- [Laughs as the bell of the church tower right next to us starts tolling.]

Here’s the fun part.

The bells! The bells! [Talking over the bells now.] Yeah, so the story suddenly started falling into place, to become this gothic-y horror kind of thing, and then the idea of this God of Tremors started to come into place. And I guess fell some more into place when it struck me that to have an interesting idea of a god was to set it against the kind of god that child may have in the Victorian era, when as the result of the Enlightenment the whole idea of this Christian god was being challenged by science. So then these elements started to come together, and I could tell my story about this young kid with epilepsy, who has his hands tied behind his back, and finds this creature in the garden who he—if you like—imbues with certain powers over his epilepsy. And I guess that was some kind of way to control the uncontrollable. Because one thing you feel while having a seizure is just how out of control you are. We sort of take consciousness for granted, the consciousness of who we are. But when you have a seizure, which is just some glitch in your brain, you all of a sudden come to realize how tenuous consciousness is, this very thing through which we experience the world. And in the book there’s a scene where he [Aubrey, the young protagonist of God of Tremors] talks about how he feels that consciousness is this thin layer of ice that he’s walking on. And how he had that feeling like this thing that we take for granted could crack at any minute and you could fall off into unconsciousness. So that was a way in which I could use some of the things which I had gone through.

In the book, while there is some horror to the seizures themselves, I thought the most horrific thing was actually the society around this boy. That the actual horror of this book--

Completely.

--is the patriarchy, the Christian morals, the corrupt scientists and doctors--

Yeah, like the way the mother was treated. This idea of “moral insanity” was a thing in the Victorian age. Guess what, it was always women who were morally insane. Usually if they’d had an affair, or certainly if they wanted to separate from abusive husbands. It was better for the husbands to have them locked away to maintain some control over them.

So it’s all a function of social control, really, tying back to this idea of “normalcy” that you mentioned.

Yeah, absolutely. [Bells stop.] And I suppose tying this kid’s hands behind his back when he goes to bed is a very physical form of social control, and the desire to control. Yeah, so that’s where it came from. That’s a good example of a, if you like, inchoate idea. Which is to say you have some things you want to write about, but the story isn’t quite there yet. And I think it’s best not to force it. Just let it percolate, and just to have it there, maybe do notes, and then maybe return to it a bit later. Because then often you return to it with something, another aspect, another thing, and things can fall into place - or not. I mean, some stories just don’t happen. But sometimes they do.

At what point did Piotr Kowalski get involved in the book?

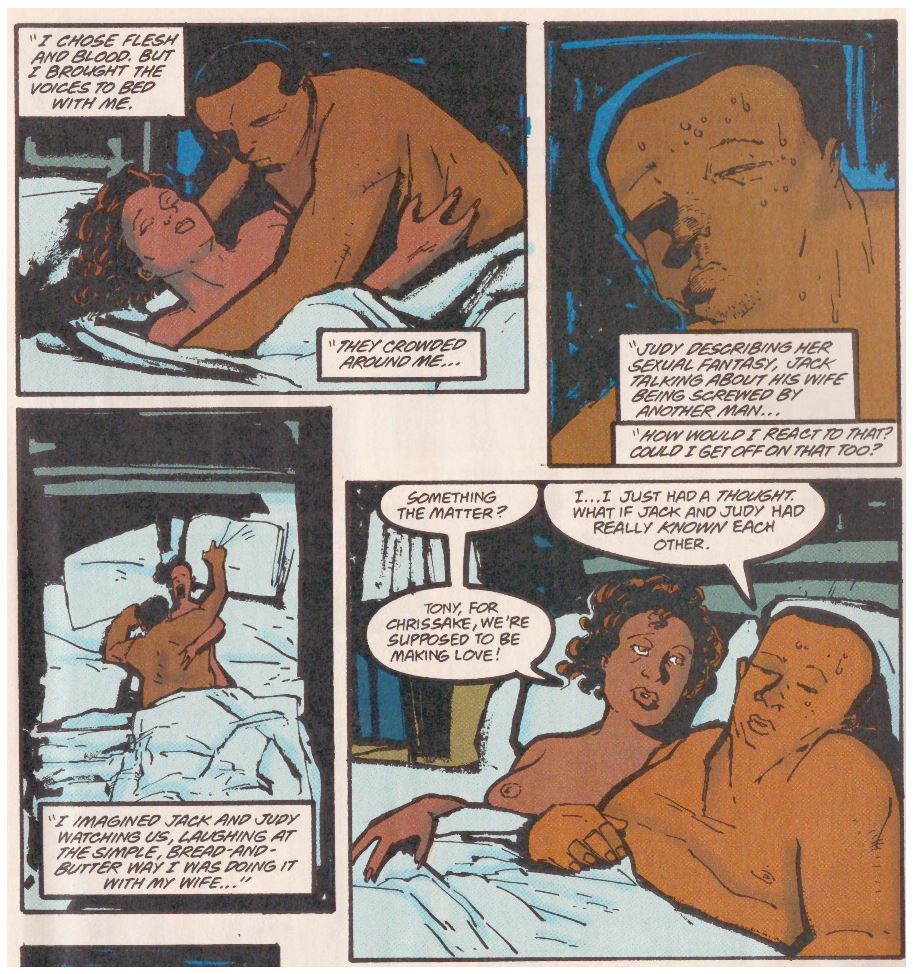

We’d been talking, and Piotr had been sending me some of his artwork, and we were talking about maybe doing some more work together. I think he’s got quite a distinctive style. So I talked to Mike Marts, our editor, about Piotr, and he said he’d be really happy with Piotr because he’d used him before. I looked up a bunch of Piotr’s work, and he had this slightly, almost overwrought style of artwork. I mean, it’s very kind of worked, and it’s very kind of almost slightly uncomfortable. There’s not a lot of space in it. The amount of inking he does is quite a lot, and I think a purist might say too much. But it felt right for this story, which was about this person whose life was being controlled, and everything was closing in on this person’s life. And so Piotr’s artwork appeared to be just right for this slightly uncomfortable, slightly nervous and difficult kind of story. I didn’t want someone whose style was too pretty. So sometimes someone’s just right for the story, and sometimes it’s for strange reasons. Back when I did The Extremist, which was a very sexual story, I remember saying to Art—again, Art Young, who was our editor—I didn’t want it to be just a wank mag, you know. I didn’t just want it to be lots of pictures of beautiful girls with big breasts and big asses for the boys to love. So I wanted to desexualize that a bit, and so that’s why Ted McKeever was perfect for that, because his bodies, his humans, are so uniquely his, so odd and so almost, like, divorced from “normal” sexuality that it just seemed so perfect, because it was a way of making it not just some glossy titillation. Rather, it was something through which we could then concentrate on what it was really about.

How has the work process changed between the early 1990s—when The Extremist or Enigma came out—and now? Are there any fundamental differences, or things that--

Well, Vertigo doesn’t exist. For writers like myself, doing the kind of stories I want to do, obviously at a certain time Vertigo was the perfect home for me. So that doesn’t exist, and that changes things. But I think Vertigo’s effect on the industry is intact. It changed the way lots of people thought comics could be done, or what comics could be. And I think a lot of smaller companies, like AWA, and AfterShock, and Vault Comics also, I think they’re doing the kind of comics that wouldn’t have been out of place in early Vertigo. Because this is our idea of what a Vertigo comic could be.

In terms of the process, was there more collaboration between writers and artists in the early 1990s, or is there more now? Has the way of collaborating changed at all?

No, I think the big thing that Vertigo did was to really, if you like, not have the auteur idea of story, but get a sense that the writer’s or the creator’s vision was really important. That comics creators had a vision, and there was a creative necessity for them to tell a story. And I think that’s the thing that Vertigo changed. And a lot of these other companies carry that forward. I’m not sure if there’s any more or different kind of a collaboration. Different projects might demand a more collaborative kind of story, but generally I talk to the editors if I have an idea, we talk about it, sometimes we finesse it, sometimes we elaborate it a little bit. Sometimes somebody comes up with a good idea that I haven’t had. And then what you try to do is, you try to convince yourself it was your idea in the first place anyway, and you use it.

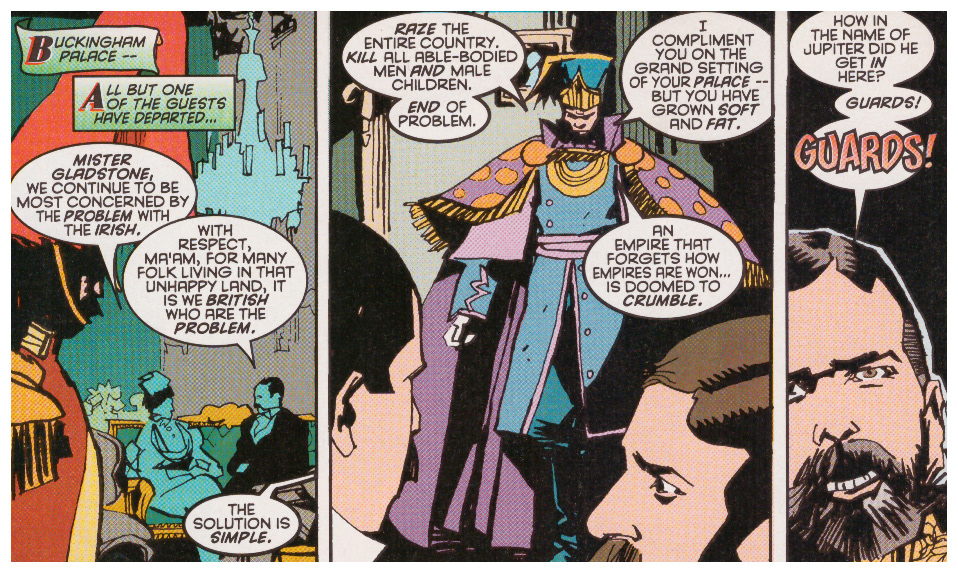

Speaking of the Victorian world, I want to go back to the first comic by you I read, which was, I think, The Further Adventures of Cyclops and Phoenix--

My god. My god.

Yes.

See, that was a very different kind of comic.

Right.

They weren’t my characters and... so that was very collaborative. Of course I worked out my idea for the story, but then they [Marvel] would be quite clear about perhaps... perhaps spelling stuff out more than I would naturally do, because that’s how they wanted to do their comic. So I want to say the difference between that and, say, God of Tremors, is huge. The difference between the comics I did for Vertigo and God of Tremors is negligible - they’re of the same stable, the same way of doing comics. Cyclops and Phoenix, they were established characters who you don’t have a lot of wiggle room with. You try to have some good ideas, you try to kind of make them your own for that short period when you have them. But you ultimately hand them back, and it’s their characters.

But you did collaborate with Leonardo Manco and John Paul Leon and Kelley Jones on your early Marvel projects - all artists who could have worked, and later did work, for Vertigo. So how--

But back then, Vertigo wasn’t what it is now. We now look at Vertigo as this great thing. But I think some people wanted to draw superheroes, and some people wanted to draw those kinds of big hitters. And Vertigo was often strange little stories. Not everyone wanted that. So I don’t think Vertigo was keeping them out.

How did Marvel contact you?

Probably at a comics convention. I probably met someone who said, “we’d like to work with you.” But I can’t remember the exact occasion. It was all quite painless, anyway.

I recall being disturbed by this comic, in a good way. It’s very dark, and it’s got some horrific stuff in it, like--

Well, I wanted to bring that kind of British-- not Elephant Man, but that dark side of the Victorian world, and also the whole idea of the Enlightenment was going on. Stuff about burials, and dead bodies, body-snatchers, you know. So you try to bring this other stuff to these characters. And also, I think I was exploring the American idea of Manifest Destiny, because it was interesting to me at the time.

You added a lot of background, and a lot of authenticity, I thought, to characters like Mr. Sinister and Apocalypse, who were literally action figures at the time.

I think you have to take them seriously. If you don’t take them seriously, you can’t expect anyone else to take them seriously. Even if they’re.... It doesn’t really matter what they are. It could be the Wooden Man, just kind of like a person made of wood, but you’d still have to take that kind of character seriously. They have a character, they have a background, they have an objective, and they have loves - or maybe not loves. Also, I think that when you can’t change the main characters that much, like Cyclops and Phoenix, like Batman, you try to make the scene, or make the setting another character which you can change. Because that’s yours, you know. And perhaps that is one reason why you can work with these characters and still have it feel like it’s your story, because you’ve added this whole other thing which is very mutable. Unlike Batman or Cyclops or Phoenix.

There’s this bit in Sub-Mariner: The Depths--

I love that story!

--where one of the U-boat men gives the sea-sick scientist this pill that he says is made of “a little crushed mermaid fanny” among other things, to which the scientist says: “I guess if it helps my breakfast stay down, I’m willing to suspend disbelief just this once.” Is this basically you when somebody hires you to do some of these characters?

[Laughs] Nooo.... But I see where you’re getting that, like it could be some encoded message. But no, I think not. I was just doing the story, and obviously--

Not even a little bit?

Maybe in some kind of unselfconscious way. [Switches to German] Vielleicht auf eine unbewusste Art.

You told Nick Hasted in 1997 that you had a destructive side, that there was a need for you to go and do something self-destructive at times, and you felt like chaos was always just around the corner.

Oh. Yeah.

Is this still something you feel is true today?

Look.... Yes. And I think one gets better using strategies. My epilepsy was very late in coming, I think it was after that interview. And certain things happen when you have epilepsy. You have to take control of that chaos a bit more, because it will kill you. So what I was saying back then probably was, yeah, I had this crazy side. And you just have to not give free rein to that crazy side as much, because the consequences, when you have epilepsy, can be brain death, or severe injury. So you have to kind of reel it in a bit. And when I got epilepsy, the chance of me dying from epilepsy obviously increased. But also the chance of me being stabbed in a pub in Finsbury Park at two in the morning drunk and on cocaine probably decreased an awful lot, you know. But I didn’t mean to say you need to be crazy and do crazy stuff to have crazy ideas. But I think you still try to ferment the kind of chaotic quality inside the brain, to have this kind of ferment of ideas and feelings. Because it’s a strange thing, isn’t it, writing? Saying I’m going to now imagine myself into this person’s thoughts and prayers, and now I’m going to imagine myself into doing this, and now I’m going to have these people walk around, and I’m going to try to make it all mean something. And no matter if it’s films or a poem or a comic book, it’s a strange thing, this storytelling malarky. But it’s something that humans do. Maybe it’s the defining thing of making us human that we tell stories. That we make stories up to have a meaning. It seems to me that’s quite unique. As unique as these strange thumbs we have, and walking upright as an ape. That’s not a bad way to end, is it?

Do you still play music?

I play guitar every day.

Speaking of thumbs.

Yeah, work thumbs. [Laughs] Yeah, I’ve got some good guitars. I want to play more acoustic guitar, really. Yeah. But with work, the guitar, and with trying to improve my German, there’s not much time left - and reading, of course. We have to read to be smart.

* * *

- [Editor's Note] Since this interview was conducted, AfterShock Comics filed for bankruptcy under a cloud of allegations of late payments or nonpayment to creators. Peter Milligan Creations is listed among the creditors in the bankruptcy documents. Milligan did not respond when asked for comment.