This is John and I'm flying solo this week, as Frank Santoro just got back from England, where he was attending the Lakes Festival. I'm sure he'll fill us in on all that next week, but in the meantime, you can check out the plans Frank has to create a brick and mortar school for cartooning HERE. I know the fundraiser for the school is going strong and amazing premiums from famous cartoonists continue to come in.

As we said last week, the inaugural Cartoon Crossroads Columbus event (CXC), held mostly on the campus of Ohio State University in early October, was a terrific time and one that gave historians of the field ample material to digest. This week we will focus on the keynote event of CXC, a panel in which the co-founders of the influential RAW magazine-- cartoonist Art Spiegelman and his wife, The New Yorker Art Editor Françoise Mouly--discussed the early days of the magazine with cartoonist Jeff Smith.

The sprawling discussion ranged from Spiegelman's involvement with Arcade, the comix magazine he co-edited with Bill Griffith in the mid-1970s, to Mouly's various temp jobs and attempts to broaden her command of the English language via reading comic book, to Spiegelman's friendship with comic artist and historian Woody Gelman while employed at the Topps bubblegum card company, to his early attempts at creating what would eventually lead to MAUS, his Pulitzer Prize-winning graphic novel, as seen in the video below:

In the clip below, Spiegelman and Mouly explain what they were looking for when they assembled the artists that appeared in the first issue of RAW:

Mouly described how her interest in the printing process--and dissatisfaction with commercial printers--eventually led her to acquire her own printing press, which was used to self-publish early issues of RAW and other projects. The printing press, a giant AM Multilith machine, needed to be lifted to get it in to their illegal SoHo loft, which, since their building had no elevator, was not an easy job.

Mouly explained that the early projects created with her printing press included local business street maps/guides that she and Spiegelman made in effort to make some money, as well as stickers, postcards and other small projects for their cartoonist friends.

One of the first of these was a Zippy-Scope (above), an ambitious spooled-reel toy of sorts that took 287 wordless panels of Bill Griffith's famous Zippy character (from a tale called "The Enigmatic Donut") and placed them in a printed cardboard viewing contraption that looks a bit like the cheap disposable cameras of the 1990s. A total of 100 signed copies were created and you could view the Zippy strip by turning the device's handle counterclockwise to see the panels one at a time through a clear plastic window. In the clip below, they discuss the process of naming RAW, as well as how the Zippy-Scope was constructed.

In an email, Bill Griffith explains, "The drawings in the Zippy-Scope are taken from the center spread of my comic, YOW #2 [Last Gasp, 1979]. In the comic, it's called 'The Centerspread Caper,' 280 little panels in all, across two pages. Art and Françoise were impressed by the craziness of this piece and came up with the idea to make it into the Zippy-Scope. Françoise printed all 280 little panels (plus seven more for 'front matter') in sequence on two long turning spools inside a box,

viewable one at a time through a little plastic window. Now who's crazy? Art and Françoise made a few for themselves and I got five 'artist's proofs,' of which I still have two. I also did a flyer which was mailed out to potential buyers."

Copies of the rare item have been listed for up to $1,200.

---------------------------

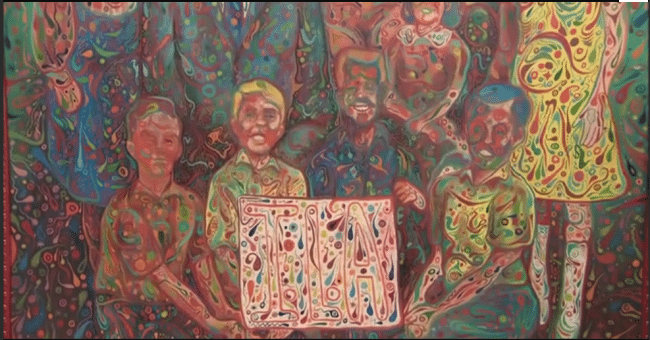

Lost Jay Lynch Painting Featured on Roadside Antiques

The other underground comix creator that we will check in on this week is Jay Lynch, who was in the news thanks to the discovery of a "lost" early painting he created in the mid-1960s. This week's episode of the PBS program Roadside Antiques ran a segment in which an appraiser examined a painting by Lynch and concluded that given the work's condition--it has "a couple of little punctures and tears" in it--it was worth between $5,000 and $7,000. The painting, described as "trippy" on the program, was created as a class assignment when Lynch was a student at the Art Institute of Chicago and features a happy family scene in which some members hold up a sign with the letters "ILA" on it. The program concludes that, given the psychedelic paisley swirls that mark the image, the lettering is shorthand for "I Like Acid" and says that Lynch was "perhaps under the influence" when he painted it.

Well... I asked Lynch about the painting.

"I think I did this in '65 or '66... before the Summer of Love," Lynch says. "I don't think there was any LSD art [back then], but there was LSD. But I didn't take it at school. I took it at home, but it stayed with you, the memory of it, you know?"

Lynch says that while he was a student at the Art Institute in the mid-'60s, there was a billboard across the street from the school that advertised the political campaign for a local sheriff. "It showed this guy and his wife and like eight kids. And the kids were holding a sign that said 'Woods For Sheriff' and you could see the billboard outside the window of the art class. So I painted it. But then I got carried away. I was just trying to kill time really, and I painted it for months. After a while you put it up in front of the class and the teacher critiques it. And so the teacher says, 'Well, what were you thinking when you did this?' And I gave this sort of long-winded speech about when certain things affect the brain it allows you to see the plasticity of your environment, blah, blah. After I got done with that, he said, 'Oh thank God. I thought you were taking LSD or something' and that got a big laugh."

And what happened to the painting?

"I gave it to some guy in 1966 and he gave it to his girlfriend in the '70s and then that's the last I saw of it," Lynch says. "Then this guy found it in a dumpster 15 years ago on the other side of town, so I don't know where it's been for the last 40 years. And then he called me before he went to the Roadshow thing and asked me what the deal was."

So, was Lynch in fact tripping when he did the painting?

"Uh, yeah. I was tripping... Not when I was doing the painting, but around that time, yeah. I was art school and this was before there were hippies... and they're not 'paisleys' that I drew [on the painting]. They're like vitreous humours, the things that float around in your eyes, or the spots when you look up at the sky. When I was a kid, there was an article about MAD in Pageant magazine in like 1955, and on another page there was an article called 'Pills Chase Away the Blues' and it was about LSD. I guess I read it when I was a kid. I tore out the Kurtzman part and I saved that. [The other article] said that if people take this thing called LSD, they see these two Disney dwarfs--a black dwarf and a white dwarf--fighting, and they spin around in a circle and they turn into a yin and yang. And that's what I saw, because I had read that, you know, 10 years before. So, it was a 'suggestion' [from the article]. An 'implant' is what Scientology calls it."

Lynch says he painted the image on a $5 piece of canvas that he stretched himself and nailed on to the frame.

“It’s an oil painting and it’s a linen canvas and it’s stretched. I bought pre-cut canvas and it cost me like $5 in 1965, but I had to gesso it myself. I had to paint white on it myself,” he says. “They disrespect these store-bought canvases because the store-bought canvases are cheap cotton canvases and this was a linen canvas, which cost $5, which was a lot of money back then. I looked up this canvas company—this is what canvases cost now—and a canvas this size, pre-stretched, a linen canvas—is now $500. So, I don’t know… I should get more now [for my art]. I must maximize my income. I’m still getting what I was getting in 1975 for these paintings. I never sold my paintings for a lot [of money] but the ones who sell my paintings get a lot."

Lynch added that at the time he did the painting, LSD was legal. You can view the episode HERE.