Xeric award winning graphic novelist Kevin Mutch discusses his work including his new book, The Rough Pearl, as well as the relationships between cartooning, the fine art world, the price of living in New York City and making a living (or not) as a “creative.” He barely even touches on the subject of zombies.

Xeric award winning graphic novelist Kevin Mutch discusses his work including his new book, The Rough Pearl, as well as the relationships between cartooning, the fine art world, the price of living in New York City and making a living (or not) as a “creative.” He barely even touches on the subject of zombies.

Thanks so much for the interview, Kevin! Let’s start with a “big picture” question: what are your thoughts on the role and purpose of art in society?

Heh, I’ll go full “evolutionary psychology” here and say that I think that -- at root -- we’re inclined to make art for the same reason bowerbirds build their elaborately decorated “bowers” - as a display of fitness and of access to resources. In that sense, the evolution of apparently “wasteful” behavior like art would be an example of Darwin’s idea of “sexual selection” - the behavioral equivalent of a peacock’s tail.

Having bought into that view, I'm not surprised to see fine art mostly used to signify and support wealth, power and status rather than criticize or interrogate it (despite all those bohemian claims to the contrary). I wholeheartedly believe in the possibility of critical art though - I think the best art calls things into question.

The problem for traditional art forms like painting and sculpture is that they generally exist as unique objects, which allows any criticality they do possess - any calling into question - to be defanged by their own patrons. The wealthiest people in the world can buy the most radical art in the world -- and lock it up in their homes (or more likely, their high end storage facilities) for decades, or at least until it’s safe to donate to a museum.

That’s what’s so great about what the art world calls “multiple” forms like music and books — where it’s possible to disseminate art to anyone with a few dollars. That type of art is much more slippery and insidious - way harder to control!

On that theme of calling everything into question, please tell me about how your two graphic novels, Fantastic Life and The Rough Pearl, are concerned to do exactly this. Both works are set against backdrops of art worlds and academia. Fantastic Life takes place in Winnipeg, Canada, and the story involves multiple or many worlds theory. Anything you can share on this, and also regarding the fascinating idea of ‘appropriation art’ in relation to meanings, explored to great effect both here and also in your Captain Adam work?

On that theme of calling everything into question, please tell me about how your two graphic novels, Fantastic Life and The Rough Pearl, are concerned to do exactly this. Both works are set against backdrops of art worlds and academia. Fantastic Life takes place in Winnipeg, Canada, and the story involves multiple or many worlds theory. Anything you can share on this, and also regarding the fascinating idea of ‘appropriation art’ in relation to meanings, explored to great effect both here and also in your Captain Adam work?

Okay, well, I suppose you could argue that there’s a lot of common ground behind “postmodern” strategies like appropriation and the implications of quantum mechanics. The history of the two movements is similar too – both had their early beginnings (considering Dada as a PoMo precursor) around the turn of the last century, both developed a lot during the first World War - often in Zurich! – and both came to fruition by around the 1960’s.

More to the point, both of them have at their core the idea that there’s no fixed single “truth” (speaking of calling things into question!) Instead, the world is seen as relative, conditional, contextual – something that changes with every new perspective.

Hugh Everett’s “Many Worlds” interpretation famously claims that the apparently singular universe we find ourselves in is actually just one iteration (or maybe inflection) of a “Universal Wavefunction” in which every possible universe actually exists, simultaneously. So reality itself is totally probabilistic in quantum mechanics.

Meanwhile, appropriation art has always used what John Cage called “chance operations” - the introduction of randomness into artmaking. In the case of my Captain Adam comic the entire story was made with a random process by cutting up a stack of old comic books into a pile of their smallest narrative unit, the “panel”, and then combining them blindly to try and create some sort of new narrative. A lot like William Burroughs’ “cut-ups” strategy, but with pictures too.

Those “swiped” drawings carried a lot more freight than the dialog - it was usually obvious that they were coming from totally specific genres, each with their own associations and tropes - so much so that I had to redraw them all and tone down the disjunctions a bit before anyone (besides me) could follow the “story” at all. I really liked watching all of the old meanings change as the cut-out panels (I called them “narremes” after the idea of “phonemes” in linguistics) jostled into each other in their new contexts.

In my Fantastic Life book the protagonist Adam explains to a woman he’s trying to impress that his painting “When Pussy Gets Her Back Up” isn’t meant to be misogynist — he sees it as an example of how a change in context (in this case solely due to the passage of time) can create a change in meaning -- from something charming and innocent (a child’s book illustration) to something deeply troubling and problematic (a monstrous vagina dentata).

Ironically, his entire life seems to be undergoing a similar process -- because he keeps waking up in unfamiliar situations where the whole world has changed around him. The explanation he’s given, by an undead character who calls himself the “philosophical zombie,” is that he’s careening around alternative realities - the “Many Worlds” come to life. To escape this, he’s forced to pour out his heart - literally his “expression” as an artist.

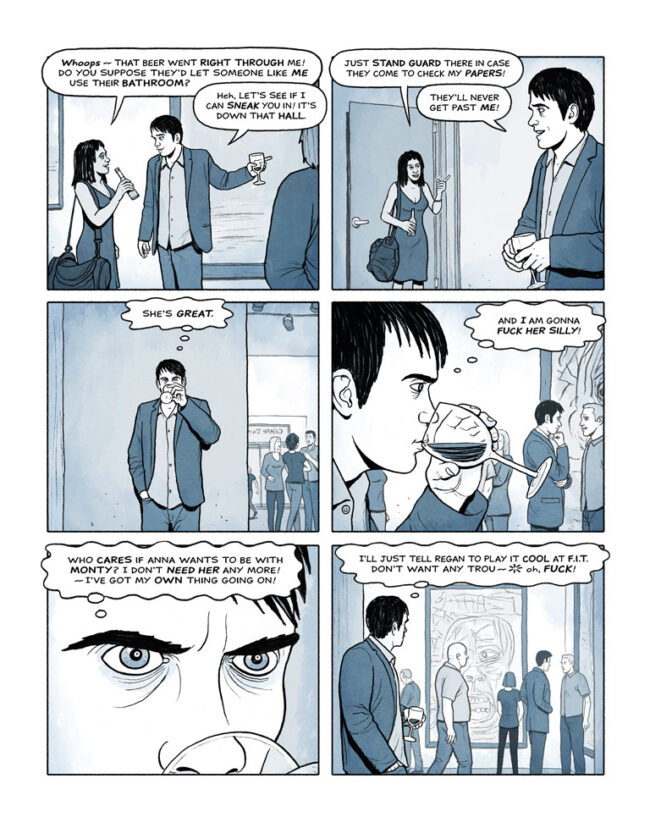

Adam is also the “hero” of my book The Rough Pearl - a sequel which finds him a little older, living in New York City (okay, New Jersey!) and trying to hold onto his grasp of a single unitary reality with the aid of antidepressants. He’s still making appropriation art, but now he uses a computer to smoosh photographs from pornographic magazines around until they look like Expressionist paintings. So his “expression” is actually a Conceptualist strategy - and still heartless!

The Rough Pearl addresses issues surrounding the intersection of class and race privilege in the “precariat” creative communities in and around New York City. To what extent is your work semi-autobiographical?

The Rough Pearl addresses issues surrounding the intersection of class and race privilege in the “precariat” creative communities in and around New York City. To what extent is your work semi-autobiographical?

I’d say it’s a roughly 50/50 combination of biographically accurate facts and invented fiction. For example, Adam lives in Union City, NJ and teaches at the “Fashion Institute of Manhattan”. I lived in Union City, NJ and taught at the “Fashion Institute of Technology” in Manhattan. The whole story arc about Adam meeting an art world heavy hitter and his protege/boyfriend who offer him a shot at the big time, only to have it completely bolloxed up by misinterpreted sexual overtures - that’s all based on stuff from my own life (seriously!).

On the other hand, Adam is presented as trapped in a dying marriage and yearning for one of his students, Regan, who’s based on my wife Melissa. But in reality my wife and I met very innocuously through a mutual friend - she wasn’t a student (let alone a stripper, which is how Regan supports herself). The idea of a prof dating a student came from when I was in art school in the 80’s - it was a common scenario back then. Having the student be a stripper was based on an article I read about an old strip joint in Manhattan where students from F.I.T. and other art schools would dance to pay for school.

So, to answer the rest of your question, the class and race issues that get -- I won’t say “addressed”, but raised -- in the book are very much based on my own experiences. I’m from a traditionally blue-collar background in the sense that my father was a policeman in Canada — a mountie, in fact! — but I was able to go to university and grad school because it was very affordable to do that in Canada in the 1980’s. When I moved to the US I found myself in a weird outsider/insider position as a white/male/credentialed member of the “creative” class -- but also a dirt poor immigrant.

And meeting my wife there was an eye-opening experience - she’s Black, and also an artist, but she grew up poor in Baltimore and couldn’t afford college. Like a lot of people from my background, I grew up watching US cable TV and wondering why African-Americans didn’t just “get over it”, so I’m lucky my wife has been patient and good-humoured enough to explain that all to me in great detail. Although I hope that living for a couple of decades in inner-city New York and Los Angeles would’ve been enough to open my eyes anyway.

At any rate, we both spent many years as members of the “precariat” as you say, trying to be artists and struggling to make a living. We were lucky enough to be able to scrape by and raise two kids, but it got increasingly difficult in recent years as the cost of health insurance and education (to say nothing of the political situation) got out of control, and all the work available trended toward “gigs”. So in 2018 we moved to Canada, which was extremely difficult (and shocking for our kids) but I think the right thing for us.

Please tell me about your webcomic, The Moon Prince. What inspired and motivated the project?

Please tell me about your webcomic, The Moon Prince. What inspired and motivated the project?

I was a voracious reader of pulpy old adventure stories when I was growing up - especially the science-fantasy books Edgar Rice Burroughs wrote in a genre called “planetary romance” which were set on Mars or Venus or the Moon, and also his Tarzan books set in Africa. When I had children of my own I looked forward to sharing these stories with them, hoping that they might be as exciting for them as they were for me.

But I also realized that these books would be problematic nowadays, because the protagonists were always white males encountering primitive tribes and conquering/enlightening them with their superior knowledge and technology — colonialist fantasies, in other words. Also, my children are biracial (Euro-Canadian and African-American) so I try to give them a lot of context when I show them something that touches on these issues.

With all that in mind, I sat down with my son and picked up one of my old Tarzan books — but it was so immediately openly racist that I couldn’t bring myself to read it aloud to a ten-year old, not even as a “teachable moment”. I just wanted to shield my kids from that poison. So that was a real disappointment.

Then a while later I was watching TV and an old movie version of HG Wells’ The First Men in the Moon came on - the 1963 version - and it had this crazy charming “steampunk” quality, where these Victorian explorers were claiming the Moon with a Union Jack! I was thinking about how that sort of “alternative” history could give you the freedom to reimagine anything (just like “many worlds”), and it occurred to me that I could write a “planetary romance” set in that same sort of turn-of-the-previous-century environment, but turned around - showing the other side of the colonialism story.

And from that, it was a very short leap to imagining kids of colour like my own as the heroes - going into space and having those adventures but without all the conquering of ignorant alien tribes - just the opposite in fact. So I laid it all out as roughs for a graphic novel and then got my children to pose for it (and my wife - she plays an African-American space pirate). They were total troupers, but it took several years of posing every weekend - I had to hurry up before the kids got too big for the roles!

How do you feel the work resonates in terms of inequalities, both historically and in terms of contemporary society, today? Put another way, what does the work say about the world, in your view, and about people’s experiences in the world?

How do you feel the work resonates in terms of inequalities, both historically and in terms of contemporary society, today? Put another way, what does the work say about the world, in your view, and about people’s experiences in the world?

In the case of The Moon Prince, I’d say that the piece is aimed at the historical inequality of how adventure stories are presented. So it’s actually not as much about the all the racism and inequality the protagonists experience (they’re indentured servants, not much better off than slaves, and get referred to by their overseer as “mulattoes”) as it is about addressing a longstanding (and ongoing!) problem of representation in popular culture by who the protagonists are. I wanted my biracial kids to see a story where people who looked like them (exactly like them, since they posed for it!) would be the heroes at the heart of it.

Shortly after I started posting it online, I had an email from a reader who told me that her kids were biracial too and that it meant a great deal to them to see those characters. Needless to say, that’s my all-time favourite comment.

In the case of The Rough Pearl, which is a very different type of story, I suppose I’d like to think that people would recognize some truth in it about how tough -- scary in fact -- things are starting to get in America, but also see some possibility of hope and reconciliation. I was pretty shocked by the levels of inequality I saw when I first moved to NYC in the 1990’s, and they were so much worse by the time I left that it felt a bit like running out of a burning building!

But having said that, many of my experiences there were of extremely diverse groups of people coming together to work and play (and have babies) across every sort of colour and religious and sexual line imaginable -- people from many worlds! So I’m still hopeful, and I hope that comes across in my books.

In terms of your cartooning thus far, which work do you see as your magnum opus?

Well, a magnum opus implies a certain heft, and The Moon Prince will be 421 pages when complete (I’m almost there, after 10 years!) which is a very long work indeed by graphic novel standards - it’s meant to be broken up into a trilogy actually, so as not to intimidate anyone! However, in terms of the work which I hope has the most -- let’s say meat on its bones -- I’d go with The Rough Pearl since it tries to get into a lot of ideas that have preoccupied me for most of my life.

For such a maligned medium, there’s plenty of room in comics for detail and subtleties in the drawings and texts that can feed into and complicate each other. The more comics I’ve made the more convinced I’ve become that they can be as deep and rich and problematic -- can call as much of the world into question -- as any other type of art.

Can you please explain what you mean when you say that comics are a ‘maligned medium’? And what are your thoughts on the cultural position of comics today?

Comics in North America have usually been thought of as a lightweight entertainment, produced mostly for children. This is changing as graphic novels and graphic memoirs and so on gain greater acceptance in academic and high(er) culture, but it might be a Pyrrhic victory given that the entire model of publishing books on paper -- of reading, in the sense that existed when I was young -- is withering away in the face of video games, movies, streaming television, the internet, social media etc. “Web comics” is the obvious way forward, I suppose, but I think we’ve already seen that longer, deeper, difficult stories don’t do as well there.

So given that, I’m not sure if serious “graphic novel” comics have enough time to survive their current, uh, “pupal” stage and emerge as a fully fledged high art medium — but maybe they will. I just hope they won’t be as marginal as, say, poetry!

Please tell me about Blurred Vision, and please share your thoughts on the reception the works received from the mainstream comics press. And what do you feel can be said of the reception, looking back, in relation to popular perceptions of comics, and the places that art, narrative and comics occupy within the broader cultural landscape, and their potential?

Please tell me about Blurred Vision, and please share your thoughts on the reception the works received from the mainstream comics press. And what do you feel can be said of the reception, looking back, in relation to popular perceptions of comics, and the places that art, narrative and comics occupy within the broader cultural landscape, and their potential?

Blurred Vision was an anthology series I co-published and co-edited in NYC with my old business partner Alex Rader in the mid-2000’s. At the time, the focus of “alternative/indie” comics scene in North America seemed to be moving away from “autobio” or “literary” comics such as Chester Brown, Julie Doucet and Seth produced here in Canada, or Chris Ware, Harvey Pekar and Dan Clowes in the States, or Eddie Campbell in Australia.

Maybe as a reaction to that previous emphasis on ideas and story, a lot of younger creators were gravitating toward “art comics” -- comics that focused on formal qualities like the styles of the images in a comic or the use of panel arrangements and colour. Often they were overtly influenced by 1930’s Expressionist painters and printmakers like Max Beckmann or Käthe Kollwitz, and also ’60’s Pop surrealists like the Hairy Who, and ’80’s neo-Expressionists like Sue Coe or Francesco Clemente. Oh, and Philip Guston -- they usually loved Philip Guston!

Coming from a background in 1990’s “contemporary art”, which was really dominated by critical theory and Conceptualism, I was struck by the way these cartoonists seemed to be centered on Expressionist/Romantic -- let’s say Dionysian -- types of visual art as their model, pretty much as though they were the be-all and end-all of serious art.

http://thenextissue.blogspot.com/2009/07/and-speaking-of-apollo.html

So, being bugged by this, Alex and I decided to find and publish “art” comics that engaged more with Conceptualist strategies like appropriation and critical theories like poststructuralism that emphasized readings and meaning and ideas — some Apollonian work, in other words. And instead of expressive mark-making and lurid colour, we were on the lookout for comics made with photographs, or computers or deadpan drawing styles.

That type of work wasn’t easy to find! But eventually we managed to put out four issues of Blurred Vision, each with fifteen or twenty pieces by cartoonists we thought were working that angle -- or at least, were outsiders to that dominant expressionist/formalist mode. So we published work by Bishakh Som, and Flarf poet Gary Sullivan, and people from the contemporary art world like Doug Harvey and Roland Brener, people employing photography in their work like Toc Fetch or Karl Stevens, abstract cartoons by Andrei Molotiu, conceptual comics by Matt Madden, appropriation comics by Henriette Valium, digital comics by Ethan Persoff, and so on.

We were able to get distribution through Diamond so the books went out -- and more or less sank without a trace. I mean, several of the pieces made the “Notable Comics” lists in The Best American Comics and one or two were actually excerpted in it, but there was very little critical response. Heh, a well-known “art comics” figure declared that they were “beyond terrible” so I guess at least one nerve was struck!

In fairness though, I think a lot of people in comics -- even “art comics” -- are legitimately skeptical of that “critical theory/conceptual/academic” pole of the art world — what I just called Apollonian — given that that’s probably the exact part of high culture with the most historical disdain for the comics medium. So maybe Blurred Vision was doomed from the start.

What about the reception you’ve seen for The Rough Pearl? And how much of this, do you think, owes to individuals, probably precariously employed journalists, writers, as opposed to the “comics press”?

Well, I’ve been happy with the reception so far — knock on wood! Nowadays it’s probably fair to describe the “comics press” as increasingly driven by individuals, with fewer and fewer printing “presses” involved -- it’s mostly websites and blogs now. So yeah, maybe the theme of the sinking “creative class” is hitting home for people in those fields.

How do you see the economics of comics and the market for comics and graphic novels today? And where do you see yourself, your career within these contexts?

I’m writing this in the middle of the Covid crisis, so I don’t know whether to try and answer that in pre-pandemic or mid-pandemic or (hopefully) post-pandemic terms.

As a share of the cultural economy in dollar terms, North American comics peaked in the 1950’s and have been declining ever since. On the other hand, their influence in popular culture has never been greater -- in fact, it’s never been close to as great as it is now, because digital special effects have finally made it feasible to make movies and TV shows that do justice to superhero stories, and they are obviously the most popular “popular culture” in the world today.

There’s this idea now of comics - even “indie” or “art” comics - as essentially highly developed “storyboards” just waiting to be filmed, and publishers as “IP” (intellectual property) farms feeding into the movie and TV industries. And even as the absolute dollar value of comics as a product becomes smaller and smaller, their value to the broader entertainment economy has become enormous - a single superhero movie can gross more money than every comic book and graphic novel published in the US in an entire year put together!

So the economics of comics is bizarre - huge entertainment conglomerates like Warner and Disney own the biggest comics publishers (DC and Marvel) and don’t really care whether comics publishing is a viable business any more, as long as the comics IPs continue to make money as movies and TV shows. But the artists and writers making comics typically don’t have a share of the intellectual properties. They’re notoriously poorly paid and professionally insecure - a perfect example of a “precariat.”

In my own case, that’s why I make images for the music business -- where I can make a reasonable living, and make my comics on my own time, with no need to get paid (and no expectation of it either, sob!).

Why are you serializing The Moon Prince for free online?

Partially it’s just because that’s the strategy most of us employ now to get our work noticed and hopefully published on paper. But, honestly, it’s also from a need to feel like the whole exercise is part of the real world, as opposed to something that only exists in my own head (or on my own hard drive). Making comics is deeply solitary -- cartoonists often compare it to becoming a monk -- and a project like the Moon Prince, which has taken over 10 years to (almost) complete can start to feel a little too solipsistic!

What are your thoughts on race, ethnicity, identity and social class, in relation to representation, within the historical context of the comics form, and markets and the economics of art and publishing worlds? On the relative openness of the field to critical works, voices and representations? How do you feel dynamics have changed, over time, and where we are now? In looking at the present and future, where would you most like to see changes?

There’s a tension in the arts between authenticity and privilege, as in: “how can you possibly have an authentic critical voice when you operate in the art world? That’s the most privileged arena imaginable!” But in comics, as a historically populist medium produced by (usually anonymous and poorly paid) craftspeople, there hasn’t been a question of privilege until quite recently.

Instead, comics production has tended to reflect a broader pattern within American life -- immigrants or their children formed a large part of the early comics workforce, along with “journeymen” illustrators and writers who took comics work when more lucrative and respectable gigs at “glossy” magazines couldn’t be found. So as a cultural field, it was open to working class people, and to people of ethnicities that didn’t belong to the elites of that time.

On the other hand, as a popular medium it was hardly in the vanguard of criticality and representation. It’s worth noting that the highest honor in American comics -- the “Eisner Award” -- is named after the creator of The Spirit, a white crimefighter with a Black sidekick who was drawn (and written) as a particularly grotesque racist stereotype even by the standards of the time.

Comics has come a long way since then -- the advent of “underground comics” in the 1960’s opened the door to all sorts of marginal and critical voices, but that generally came at the expense of popularity. Nevertheless, there are many people working in “indie” or “art” comics today -- people who no one could accuse of “privilege” -- who feel that comics is a real and worthwhile way to be heard. Many of them print and distribute their comics themselves, which might sound like the very definition of an open field -- but it’s a hard row to hoe.

I was lucky enough to receive a Xeric award to self-publish my first graphic novel, but the Xeric award no longer exists. I was also lucky enough to have my second graphic novel [The Rough Pearl] published by Fantagraphics, but that type of publishing is under terrible strain right now because of the Covid crisis. At this point, I’d have to answer “where you’d most like to see changes, in terms of the present and the future” with the hope that we all get through this, and that change for the better will still be possible when we do.

More:

Kevin Mutch can be visited online at http://kevinmutch.com/ and The Moon Prince can be accessed at http://www.themoonprince.com/

Mutch, Kevin. 2001, July. “ArtLexis Manifesto.”

Mutch, Kevin. 2009. “Trouble with Tribbles.”