COMING UP: THE NEW YORKER, A HOUSING COMPLEX, STAINED GLASS, A FLIPBOOK

PENISTON: It sounds like you keep very busy; you have a lot of projects.

SWARTE: Yes.

PENISTON: You still do a lot of work for The New Yorker?

SWARTE: Yes. About once every month or once every three weeks, they ask me to make an illustration and I gladly do so. It’s fun to work for them. If they want me to do an illustration, they send me the article and they’re always such well-written articles and I learn so much about things I never thought I would have learned about, so I like very much to work for them.

PENISTON: You did one cover for them, right? Did you do any others?

SWARTE: No, only one cover. They asked me recently to present new ideas for a new cover so probably another will come, but you never know. [Laughs.] They have a policy that they keep things quite in their hands, and it’s probably the reason why they are so good. But I can work with it; it’s not a problem. I think the last one that I did about two weeks ago was an article about a gentleman called Mike Brown, and how he did his research on finding a new planet — it was a great story. It’s always fun to read these well-written New Yorker stories.

PENISTON: What are some other upcoming projects that you’re working on now?

SWARTE: One think I recently did is for a hospital in Nijmegen, which is a city about 120 kilometers from here, for a newly raised hospital. I made six stained-glass windows and I also did a sort of … what do you say … signalization for children?

PENISTON: Oh, signage?

SWARTE: Yeah, signage. In the hospital they have mostly numbers and letters for people to know where to go to and, if children go to the hospital, they don’t want to get lost but they don’t understand all these numbers on signs, and the hospital decided to develop a special signage just for children. There are lots of corridors in this new building, so they could easily get lost. What I found out was that it would be nice for them to follow a trace, and I had coins made, and we glued them on the walls, and they could follow the path of these coins. So if you see one golden coin on a wall and then, two meters ahead, there is another in another spot, a bit higher or a bit lower, and if you just follow these coins, you come over to the elevator to go home or at a desk where friendly people will help you. So that’s the idea. There are seven different floors with different treatments for children and each floor has its own name, and I made different designs of coins for these different floors, and there is also a coin given to the child. When the child is [admitted] in the hospital, probably with one of his parents, the child is given one coin of his floor and he can hold it in his hands and he can keep it.

PENISTON: And if he gets lost he can show it to somebody.

SWARTE: That’s right. And his parents get the same coin. That way he knows that, “My parent will always find me, because they have the coin with the name of my floor and with my design. And if he [my parent] enters the elevator hall, he can follow the coins and find me.”

PENISTON: That’s great.

SWARTE: Yes, and it’s fun. I’m doing in the center of all of Amsterdam a little, four-apartment building. And I had a presentation of it. Another architectural project is what is built now here in the center of Haarlem, just beside the theater that I designed, and that is a … I don’t know the word in English, but it’s 10 small apartments around a garden for elderly people.

PENISTON: Oh, for elderly people?

SWARTE: Yeah, mostly for elderly women. It’s a traditional form of housing for widows. And in old European towns you find these – we call it here “hofje,” which means garden, little garden. In the old towns, you can hardly see them. Mostly they’re locked up in a block. But they have an entrance door, sort of a porch, and when you go there you find a garden and around it small housings. Most of these forms are from the 16th century. In the past century, very little of them were built. It seemed to be an old-fashioned way. But people rediscovered this way of living and they asked me, together with the architects that helped me out on the theater, to design one here in the center of town.

PENISTON: So is it pretty modern-looking, like the theater?

SWARTE: Yeah, it’s modern-looking. It’s a historical thing. The principle originates from the 16th century, probably from the Middle Ages, but we do it in a modern form. And for this one in Haarlem, I designed last week a stained-glass window and a fence, which will also have a sort of a cartoon in it.

PENISTON: Are you still doing any comics, though, or cartoons or drawings?

SWARTE: Some months ago, I made a two-page comic for a publication that was done here in Holland, and about 14 comic artists were asked to visualize their favorite Dutch-language pop song. So I chose one of an unknown young pop singer, Leon Giesen, that I consider very good, and I made a comic on it. That was presented I think in February, and it seems to be quite a success.

PENISTON: In a magazine?

SWARTE: Well, in a book form with a CD.

PENISTON: Oh, it comes with a CD?

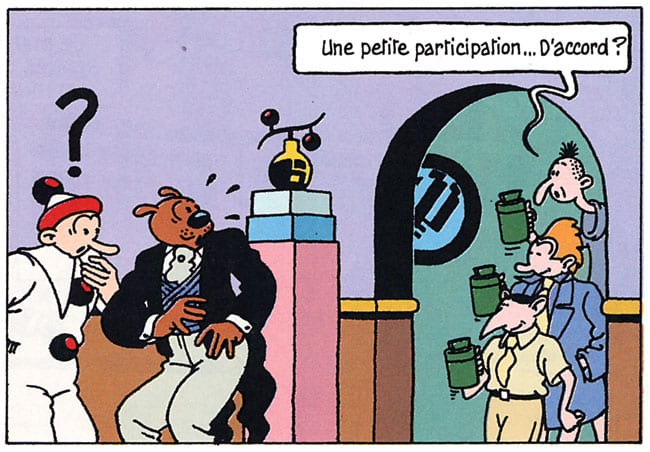

SWARTE: It comes with a CD. But it’s more a book with a CD than a CD with a book. Many different comic artists from Holland illustrated their favorite pop song. It’s called Strips in Stereo. And I almost finished, and that’s what I intended to do today and tonight, and that is work on the last illustrations of a short story of a Dutch writer who lived in the 20th century. And he had a very small oeuvre. He published only about four or five short stories and then a diary about nature. And that’s about it. But he is absolutely famous. He’s fantastic. And the story that I’m illustrating now will be published in book form, and it’s on … I don’t know the word for such a man in the English language, but it was recently translated in French, and he’s called pique-assiette, the man who picks the leftovers from the plates.

PENISTON: He’s kind of destitute?

SWARTE: Well, I don’t know. He profits from his friends. If they drink together, he never pays the bill. It’s always the other ones who pay the bill. And friends never come to him; he always goes to friends, so he can drink on their money.

PENISTON: That’s what we’d call a freeloader — or a mooch.

SWARTE: A mooch. And that’s the title of the story. But this man, when first people of his own age — I guess in the story he’s about 22 or something like it — discovered him, he seemed to be somebody with a philosophy on life and on nature and a very wise guy. But he doesn’t succeed in society. He cannot hold a job. He had something of a sort of hippie way of life. When he was discovered, he was considered to be a young man with a philosophical approach on life. When the story evolves you find out that he takes profits from his surroundings and he gets stuck in his own world, and finally he steps off a bridge. So it seemed to be a suicide in the end. I think it’s a sort of a symbol for life. People start quite positive, and after some time they find out that you can’t succeed in everything you start, and maybe you succeed in nothing you’ve started, and maybe it’s better to step off the world before the world kicks you off.

PENISTON: [Laughs.]

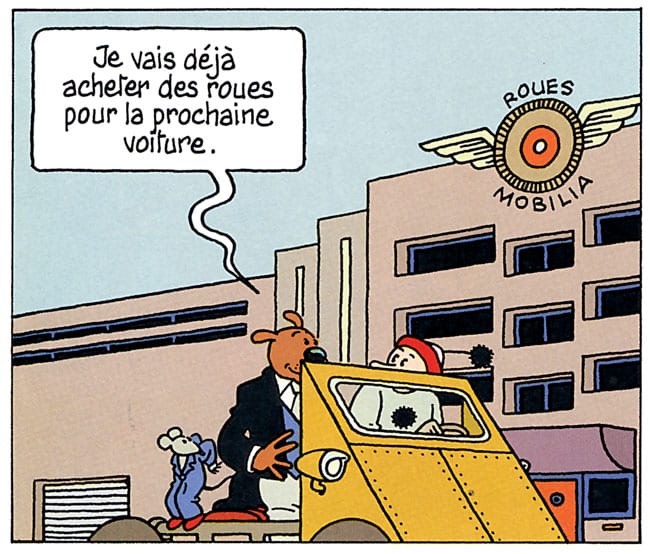

SWARTE: So it’s something like that. And I decided, in the illustrations, to place this man always in the center of an illustration — almost in the center of an illustration. And I made a sort of an animated cartoon. I always did the illustration on the right side of the right page, and if you move the pages through your thumb, you see a sort of an old movie.

PENISTON: Yeah, kind of a flipbook.

SWARTE: Yes, that’s right. A flipbook. So in this literary work I made my flipbook, and you see this character change, from his looks, from a quiet and optimistic little man standing in a world, and he gets older and lousier, and in the end he falls off the page.

PENISTON: Wow. So it’s a single illustration per page?

SWARTE: Yes. Each right page has an illustration. Now it’s a very short story, so it’s only 22 illustrations. So I forced myself to make an animated cartoon in a 22-page flipbook.

PENISTON: That sounds great.

\SWARTE: I started with the positions of the man. So that he makes sort of a curve, and then he falls off the illustration. And for that reason, the center man, I always have him printed in black. And his surroundings, and all the people around him, are printed in the second color. So that you can focus on the movement and the changes in this man.

PENISTON: Yeah, so he stands out.

SWARTE: Yeah, absolutely. That’s something that, I think we will print it this summer. And it will be published early September.

JUDICIOUS ENLIGHTENMENT

PENISTON: So you’ve been doing a lot of stained-glass work too, huh?

SWARTE: Yeah.

PENISTON: And how does that work? Do you do the sketches first and then somebody fabricates it for you? Or do you get into making the stained glass too?

SWARTE: No, there is a workshop which makes it after my designs. What I do first is, of course, I first propose a design for the people who asked for the window. And then when they agree on my idea, I finish it. I make the drawing. Let’s say, if I’m in the place and I know that a window for a specific place needs a lead line of about one centimeter large, then I scale down to my paper and I know how thick my pencil is. For instance, when a window is about one meter large, then I know I have to make it eight centimeters large in my drawing. And when I enlarge it, I come to one-centimeter thick lead line.

PENISTON: I see.

SWARTE: So that helps. And all the technical aspects I solve while drawing. For instance, if you cut the piece of glass, you can easily cut in a volume, a certain volume. Also with edges, when they are on the outside, then the glass won’t break. But if you have an edge on the inside, an inside edge, when you make for instance a hook or a capital “L,” that’ll certainly break. So you have to construct that in two pieces of glass.

PENISTON: Wow. So there’s a lot of technical stuff you have to consider in your drawing to begin with.

SWARTE: Absolutely. And then of course another limitation is that a piece of glass is never bigger than about 70 by 70 centimeters. That’s about two and half feet by two and a half feet. That’s the maximum size. And then if you have a big window, it should be divided in different pieces; otherwise it won’t be solid. It will be the unsolidness of a curtain.

PENISTON: You mean you can’t have a big piece of glass right in the middle surrounded by a lot of little stuff?

SWARTE: No, you can have a big piece of glass. But if the total of the window measures, let’s say, about six feet high and three feet large, then you have in the middle, or somewhere almost in the middle, you need some extra thing to make it more rigid.

PENISTON: Sturdier.

SWARTE: Yeah. Otherwise the window won’t be stable. So that’s another thing. So a horizontal line, or just at an angle is also OK, where you can put some extra metal in it, to make it more solid. So that’s all sort of technical things that are involved. But what I always try to do is make the drawing with the lead lines and not on the glass. If you do it on the glass, on the colored glass, you’ll keep the sun outside, and you’ll keep the colors outside. If you have yellow glass, a hundred percent yellow, it’s all the yellow which comes in through the sun. But if you make a drawing on the yellow, you have maybe 30 percent of the yellow coming in, or 70 percent.

PENISTON: I see, yeah. It blocks out the light, in other words.

SWARTE: Yeah, so I love to have the colors come in. You can also consider the stained-glass windows like a sort of huge transparency, and when the sun shines it is exposed on the inside of a building.

PENISTON: Right. How big are these stained-glass windows you design?

SWARTE: It depends. I made 34 for the apartment building in Amsterdam. Most of them measure about three feet wide and four feet high. And then after that I made one, a bigger one, for a swimming pool in the south of the country. And that was about five meters square, so it was about 16 feet large and 16 feet high. So that was huge. But recently I made the biggest ever, which is about one hundred square meters. So it’s about three meters, 80 centimeters high, which is about 13 feet high, and about six times as wide.

PENISTON: Wow, that’s huge.

SWARTE: Incredible. And that was for a courthouse.

PENISTON: Wow.

SWARTE: Yeah. [Laughs.] That was a funny commission. They had some extra money for a piece of art and they asked me to think about it, and I found out that in their entrance hall they had a problem. And the problem is when you enter, the sun, through a huge window from the central court, is coming into your eyes. Now the effect of it is that people become silhouettes, which is not quite a very social or open way for people to meet each other. I mean, it’s nice to be able to look people in the face, not to look at silhouettes. So I advised them to cover the upper part of this huge window with a stained-glass window. So they can still look into the courtyard, but the light that’s coming from above will be blocked a bit by the colored glass. Earlier on, the interior here was all painted white and these stained-glass windows I do, I don’t draw on the glass, I just use the lead in between the glass as being my drawing lines. I fill them in with colored glass. So in fact what you create is a huge transparency and if the sun shines, the whole drawing is projected on the white walls inside.

PENISTON: Then did you use darker pieces of glass, like blues or greens or something?

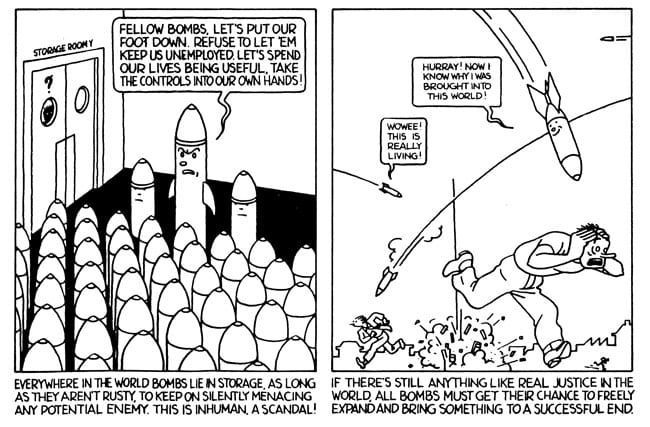

SWARTE: Yeah, yeah, absolutely. In the middle of it, that’s the place where you come in, that has the darker pieces of glass, and to the edges it’s lighter. So you come in and you can adapt to the light, and then it’s less important, but for the beginning it is important. What I first did was interview the judges. To know what they’re doing there. I mean, you know it from films or from the news on television, but I wanted to know what sort of judgments they speak there. And they do all sort of things there. They have civil rights, they have international rights, they have military rights, so it’s a huge courthouse. And I wanted to present all this sort of judging into the design. And I proposed to the judges to make sort of cartoons of what is happening in the world, so when visitors come to this courthouse and they see this image they will see, well, if it’s this bad with the world we certainly need judges to solve some of our problems that we cannot solve.

PENISTON: Is it kind of like your series of “Niet zo maar zo” dilemmas that you did?

SWARTE: Absolutely, that’s right. There is a link. And they accepted this idea, which gave me the freedom to show many things that can go wrong in life. And that’s more fun than to show people that are successful in life. So I could make quite a humorous glass window and they were very enthusiastic, they keep their enthusiasm.

PENISTON: So it brings a light-hearted atmosphere to the courthouse. Not so oppressive.

SWARTE: No, often, what they already had, they had Solomon’s ordeal somewhere, and they had also Dame Justice — I don’t know under what name she is presented in the English or American culture. A sort of a lady, who is standing, sort of an old-fashioned, I mean, from the Roman times, Greek times, an old lady standing with a scale in one hand, blindfolded, with a sword. It’s a symbol that you often see in courthouses. And I said, “Well, you have already one, so why make a double? Do something else.” And they accepted.

PENISTON: Right — we call her Lady Justice. Was that in Haarlem, or Amsterdam?

SWARTE: No, that’s in Arnhem, another town. It’s in the east of the middle of the country, about 150 kilometers from here.

PENISTON: You have your studio in Haarlem, and you live in Amsterdam?

SWARTE: No, I live in Haarlem, too.

PENISTON: Are Amsterdam and Haarlem right next to each other, then?

SWARTE: Yes, very close, it’s about 16 kilometers. That’s about 10 miles.

PENISTON: So they kind of join together as cities?

SWARTE: Not really. There is some green in between, some farms.

PENISTON: So you take like a highway to get there?

SWARTE: Well, yeah. Or you take the train. It’s about a 20-minute train ride. Or you go by bike if you want to. It’s not so complicated. Holland is quite a small country. But here, in the western part of the country, the cities are so close to each other, if I go to other cities it’s mostly 30 kilometers, or 50, or maybe 80, but that’s it.

PENISTON: Do you take the train or ride your bike?

SWARTE: Well, if I go to the seaside, that’s six kilometers, that’s by bike. When I was a bit younger I usually did in an afternoon up and back to Amsterdam. But I prefer to go by train now. And I have a little bike sometimes with me, that you can fold in two, and you can take it with you as a sort of an extra bag with you in the train.

PENISTON: Do you ultimately consider yourself more of a graphic artist, or a cartoonist, or an architect?

SWARTE: I cannot choose. I mean, it’s all fun. It’s all fun to do. You have to twist your head in another direction if you do a different job. But in fact it’s not the discipline that’s important. The creativity, the way how you come to a good solution, and the way how you do your storytelling. I mean, that’s important. If you do that in a drawing or in architecture — architecture’s also sort of storytelling — you give the people elements, you give them something like a storyteller does and they interpret like they do in a story. And if you give people different views, if you have rooms that give a certain view that’s important and that they can fantasize with, then you are sort of a storyteller.

PENISTON: Absolutely. Even in your cartoons and your drawings you see a lot of architectural elements: buildings and things like that that show up. So they kind of overlap, all these different hats you’re wearing.

SWARTE: Yeah, I think so, too. But you have to, if you make a cartoon or a drawing, you must know that this is not a building. It’s there to tell people something. So you have to think differently each time. But if you can change these buttons in your head, it can work. To me it’s inspiring. When I make a comic drawing, I dream of designing a building, and when I’m designing a building, I dream of making a cartoon or a stained glass window.

PENISTON: Right. And then when you make a stained-glass window, you’re drawing it.

SWARTE: [Laughs.] Yeah, it’s always something else.

ROBERT WILLIAMS, TANTELENY AND CHARLES BURNS

PENISTON: I heard that Robert Williams came to Amsterdam to see you. What was that like, and what’s he like?

SWARTE: Well, he was very kind. He came here with his wife, and I think together with Glenn Bray, who is a collector of comics in the United States. He works also on projects, a Polish artist who lived in America called Szukalsky. He is an interesting man, this Glenn Bray, and already when I worked in Tante Leny Presenteert, the Dutch comic, underground comic paper, he was interested in what was going on, and he had contact with the publishers of this little magazine. I don’t know exactly when this happened, but about 20 years ago Tante Leny, the wife of one of the comic artists here, started a relationship with Glenn Bray, and she’s lived already for a long time now in America with him.

PENISTON: And she’s the lady that the comic strip was named after?

SWARTE: That’s right. Leny. I mean, I didn’t name the comic magazine, so I didn’t name it after her, but her husband did. [Laughs.]

PENISTON: When did Robert Williams come to see you?

SWARTE: Ah, that must be, when was it? I think in about 1985, 1986, I don’t know exactly. They made a trip through Europe, and we always had in common a love for cars. [Laughs.]

PENISTON: Oh yeah, he’s a big car collector.

SWARTE: I remember, when I was in high school, I collected publications for hot rod cars, and there were always designs in them by Big Daddy Roth. And I loved it. They were really fun things. When I started to see [Williams’] work, and see how he did the chrome, the chrome work on the cars, I said, he probably had something to do with this Big Daddy Roth.

PENISTON: That’s right. He worked for him, didn’t he?

SWARTE: So we had some things to talk about, and I could inform him about nice European cars that I am a fan of. Not that I collect cars, I mean, that costs too much money. Too much time. You can’t do everything.

PENISTON: And you need a place to put them!

SWARTE: Absolutely. It’s too complicated. Too complicated for me, I guess. I’ve chosen bikes. Anyway, we had a good time. I think we had a dinner together. He was here with his wife, together with Glenn Bray and Leny. So it was fun.

PENISTON: You’ve also collaborated with Charles Burns on a couple of posters, right?

SWARTE: Well, on one poster.

PENISTON: On the animated film festival, right?

SWARTE: That’s right. When I started for the Holland animation film festival, they asked me to design their logo and their first poster. And for the second festival they wanted for the poster something else, but not too far away from it. And in the meeting we came out, “It would be nice to invite to each festival another of comic artist to design the poster.” In collaboration with me. That is to say: A comic artist is not necessarily also a good graphic artist. So to combine this was the idea of the director of the festival. And he said, “When we choose somebody we will propose him to work together, you do the graphics, and the artwork will be done by a comic artist.” So that seems a very good idea. So for the second festival we came out that Charles Burns would be a proper artist to invite, and he agreed on this collaboration, and he made the central drawing, and I did the coloring of the drawing and the graphics around it. And of course I discussed with Charles the details, and he agreed on it, and I’m very satisfied with this poster. It was very nice. And he came also to participate in the jury of the festival.

PENISTON: So he was there?

SWARTE: Yeah, yeah. And another time, we had a poster by Art Spiegelman, for which I also did the text, the graphics, and the control of the printing. And then we had also one by Mariscal, that we did together, the Spanish artist. And we had one by Chris Ware. And Chris asked if he could do the graphics, as well, and everybody knows that he’s a fantastic graphic artist as well, so we gave him all the freedom. And he made a very good poster. And there was one made also by a French artist called Stanislas. And he did also the graphics himself. Last year — the last festival was about two years ago — there was a 10th anniversary festival. We invited a variety of artists to participate with just a small interpretation of the logo. So we made a sort of collage poster. And now we’ve invited Dave Cooper to make one. He already did a proposition for the artwork, and I think it will be a very nice poster.

PENISTON: Are you still involved in designing the poster, then?

SWARTE: Well, not in this case. We’re still discussing it. I presented an idea, to give Dave Cooper all the freedom in the drawing, and do the coloring of the drawing, and then I could do a sort of a framework around it, in which I could do with simple colorings all the typographic information. But he wanted some time to think about it. So we gave him some time, and we’ll see how it works out. We haven’t yet decided what form we will do. But as long as it makes a good poster, I mean, that’s the only purpose. So if it came out that it’s better that he does it, let it be so.

THE CLEAR LINE

THOMPSON: One quality your work has it that you seem to give equal importance to foreground elements and backgrounds, and often you have little echoes of the storyline in the background, such as the painting of a key on the wall at the end of the Little Lit story.

SWARTE: Your question touches the essence of The Clear Line. This style of drawing makes it possible to give attention to information on foreground and background equally. All elements add something to the story. You’ll find it also in Rembrandt’s paintings. All that helps to bring the message across is welcome.

THOMPSON: Ah yes, the famous clear line. You were literally the one who coined the term “clear line,” or “klaare lijn” in the original Dutch, weren’t you?

SWARTE: That’s right: 1975, I guess it was.

THOMPSON: Did you think there was a need to define a whole movement?

SWARTE: Well, it didn’t start that way. It was just that I was invited by an art council in Rotterdam to work as part of a team on an Hergé exhibition, and when the idea of making a catalog came along, I said to the other people, “Why not make four catalogs? We have four different themes, and as Hergé mostly worked on series, why not make a series of catalogs, we’ll print on the back cover, ‘Collect them all’?” That’s a familiar phrase in the field of comics. So, then came the question of finding titles that had the same kind of impact as a book or a comic title. One of the books concerned Hergé’s roots, his ancestors. And I thought of the title “The Clear Line,” which is almost a Tintin-like title. Afterwards, referring to the people who were mentioned in this catalog, it was added, they worked in the “clear line.”

It was quite soon thereafter that “clear line” seemed to become sort of a style of working. Now, the way you draw has an effect on what you can tell or not. There is an effect on storytelling if you work with what we shall call clear line. On the other hand, the quality of Hergé is not only that he would draw in a clear line, but he knew how to make a drawing come alive, and that’s something other than the style, the façade. It’s more cinematographic knowledge that he uses to make his comic characters come alive.

THOMPSON: I looked up the Dutch word klaar, and actually ligne-claire and clear line don’t exactly have the same implications as klaar. There’s something really definitive about klaar, like “clear to the mind,” “finished” — there’s a certain authority and confidence to it.

SWARTE: Yeah. Well, it had also to do with stipulating something. The other translations emphasize more the “clearness.”

THOMPSON: Right, just the crispness of the line itself; they’re narrower, more reductive than the original Dutch term. I’ve always been interested where the clear line begins and ends… It’s not necessarily just the ones who draw like Hergé, his assistants like Bob De Moor, or Ted Benoit. For instance, would you consider someone like Franquin to be clear line?

SWARTE: Yes, yes. His early work, certainly. If you see his earlier Spirou stories, they cover the same grounds as Hergé. I mean, I know exactly what Franquin felt his roots were. But if you see what Alain Saint-Ogan had done earlier —

THOMPSON: Right, Alain Saint-Ogan was very much clear-line, and he of course influenced Hergé and therefore every Belgian and French cartoonist from the ’30s and ’40s up. Hergé is in their bloodstream, there’s no getting around it.

SWARTE: Franquin has quite a loose way of drawing, with a lovely, how do I put it, sense of motion. I just answered some questions on Franquin recently, and I think he’s really one of the masters.

THOMPSON: One thing I find interesting is that a lot of the progressive cartoonists who really changed the field tended to go back a generation, incorporating an older style. That’s the case with you and the klaare lijn cartoonists, and with the underground cartoonists who looked for inspiration in the EC comics. People like Chris Ware, Dan Clowes really also look to earlier work for their inspiration. Do you think there’s some sort inherent nostalgia in cartoonists?

SWARTE: I don’t think so. It’s a matter of studying. I mean, I never studied cartooning in art school. It was just to find out what was good and not good and to find it out yourself by doing it. As you know, I designed some covers for the Krazy Kat collections — I drew in Herriman’s style, as best as I could, just to find out¸ how did he do it? How did he make such drawings? And if you can get past that stage, then you come to the second stage, which is how to tell a story. But you have to find something. And of course, if you start looking at good comics, they’re all comics that have been published, all from the past. I don’t care if it is from 100 years ago or five years ago, a good comic is a good comic.

THOMPSON: And as you just said, an important element of the clear line is that it gives equal weight to all parts of the picture, the foreground and the background.

SWARTE: Oh yes, that’s a technical aspect of the style.

THOMPSON: It’s almost also philosophical, isn’t it? To basically say that everything is equally important, that it’s all — ?

SWARTE: It has that idea also, yeah, involved in this explanation. Yeah, I guess so. I think what cinematographers often do is to put light on the smaller detail in the background. It’s always very hard to focus on the foreground and the background at the same time. I think with digital photography, it’s easier, but at that period, if you see good, old, quality pictures, it wasn’t that easy.

But for us comic artists, we can make all the elements as sharp as we want to: whether it be foreground or background. And often, the meaning of something that’s already seen in the background comes into the story later on. It helps in building up a story.

THOMPSON: I guess sort of a democracy of information.

SWARTE: Yeah, that sounds good. [Thompson laughs.] That suits me fine.

THOMPSON: Along those lines, and maybe I’m way off base there, but it seems to me like one movie that would perfectly encapsulate this principle would be Jacques Tati’s Playtime.

SWARTE: Absolutely. That was a great movie. One of the interesting things in this movie is that there is not what would be considered a logical story from A to Z, with something of an overture etc. — it’s a collage. It asks people to look differently at their surroundings. And it’s a great film, yeah.

THOMPSON: All the information is there, and it’s not forced upon you, it’s just there.

SWARTE: It’s presented in a different way.

THOMPSON: One thing about the clear line — sometimes there’s the danger of becoming a little bit sterile, no?

SWARTE: Absolutely. Yeah, you’re right. You’re right: If you consider this to be a theory used by artists, I don’t think it’s a wise idea. You should always follow your instincts and see what’s good, to find it out in practice. It can be used by critics, by art critics maybe. But they have to be very clear on the meaning of the clear line.

THOMPSON: Ironically, Hergé himself went a little bit too far down that path. I think the monument to that was the redrawn version of The Black Island — it’s nowhere near as good as the original.

SWARTE: Absolutely. That’s what I feel.

THOMPSON: I like Ted Benoit‘s work, but there’s something really strange and ambivalent to me about the fact that now he’s doing Blake & Mortimer stories, using it almost too much just for nostalgia. It’s like the serpent eating its own tail. [Laughs.]

SWARTE: Yeah.

THOMPSON: I mean, it’s resulted in a lot of beautiful work to look at, and there are people — like certainly, Tardi — who have taken that theory and gone in interesting different directions.

SWARTE: Yeah, yeah. There is a lot of inspiring artists from the past. Gus Bofa from France is such an inspiring artist. He was also an art critic, and he was already a cartoonist in the First World War. He came back with a crippled leg. But he made a lot of limited editions, beautiful books on anxiety or the circus of life. A publisher in France who is doing a lot of reprints of his print work is Cornelius. It’s great stuff. I mean, what he expresses in simple drawings: That’s great. And, as you can see, Jacques Tardi is a fan of his too. There was a beautiful book, a selection of his work, published at Futuropolis at a time when I had my books there. From that moment on, I’ve collected as many of Gus Bofa’s works as I can get. I’m astonished with how little means, how intelligently he can tell stories in a drawing. He’s great.

STAGE AND SCREEN

PENISTON: In 1996 you produced a theater production of Dr. Ben Cine and D?

SWARTE: Yeah. Well, I did not produce; it was made after my book.

PENISTON: And that was directed by …

SWARTE: My brother.

PENISTON: Your brother. Rieks Swarte.

SWARTE: He is a theater man from his early youth. He is a theater director. And he often works with …not with written-out pieces. If he has a subject that he finds that it attracts his interest, he asks a writer, or he writes himself, to write a theater piece around it. And well, he makes beautiful things. And then there was the comic festival here in Haarlem, and he asked me if he could do a piece on this story that I once did. “Of course you can.” And I didn’t get involved too much in this production, because I knew if I want to keep my brother like he is now [laughs], leave him free. Let him do whatever he likes, and that’s important, that’s his profession, and I know that the theater profession is something else than making comics. But he did a great job. He did fantastic. It was a 20-minute theater piece. It was fun from beginning to end. It was great.

PENISTON: Well what did you exactly do? Did you design the costumes or the background, or …?

SWARTE: No, no. He adapted my illustrations, he adapted my text and my illustrations from the story, and he just did that. And we worked together on the poster. So I drew this Dr. Ben Cine character, drew the D character, and so we came together on the poster. But for the rest of it, it was all his job. I saw a run of the piece before it came out, and there was only comment on my side on one hat of the characters that wasn’t properly understood from my drawing. But that was all.

PENISTON: Oh, so he pretty much got it right.

SWARTE: Yeah, yeah, he did a great job. It was fantastic. Luckily enough, I have a tape, an amateuri video tape, but we still have it.

PENISTON: Have you done other collaborative pieces with your brother?

SWARTE: No, not really. Just sometimes — Oh! Some cat war is going on here in my garden …

PENISTON: Uh-oh. [Laughter.] Now, you mentioned you like film. Have you ever worked on any animation?

SWARTE: Yes. Yes, I did some experiments when I was still a student. But it was more abstract, and I think also influenced by McClaren, the Canadian animated-cartoon pioneer. R. O. Blechman, from New York had a studio — he still has, I guess — called The Ink Tank at that time. That was, I think, in the ’80s. He made station calls for MTV. And he asked me two times for a collaboration. So I made some, not really key drawings, but I worked on the script with some drawings, and he finished it off to film in the studio.

PENISTON: A little animation piece.

SWARTE: Yeah, a little animation piece of maybe, what are they, 20 seconds or something. Then about four years ago I was asked by the city where I live here, Haarlem, to cooperate with Gerrit van Dijk, an animated cartoonist here in town. He’s quite famous in animated-cartoon land. Together we worked on a film about the town that we are living in. We came to moving storyboards, so we have the moving storyboards, but the financing of the film became a problem, so it was never finished. But if somebody with enough money comes up, we could still finish it. [Laughs.] But it’s often if the dynamic is lost in a project … well, I guess it will never happen.

PENISTON: Computer animation is that the way art’s going to go these days, you think?

SWARTE: I don’t know. I mean, the computer helps. It’s a new thing. If I look at Shrek, the movie, here, I think it’s very good. And the Toy Story movies too. I mean, we have a lot of fun with it. But when I see a small thing, even if it’s a flipbook, or if I see an animated cartoon — I saw a beautiful one by, there was a presentation of the work of the Argentine artist Carlos Nine, in Angoulême, in France. And they showed a little animation film by him, a sort of a Betty Boop character. Something in between Dave Cooper and Betty Boop, but it was Carlos Nine. And it was so fantastically done, but it wasn’t yet in color, it wasn’t yet inked, it was just in pencil. The forms were so great. And it was a beautiful little animation. And you can see that animation is not only what you give to the people, it’s also what the people who look at the animation, they can finish it off in their head. They finish the story, just like comics. I mean, you offer them something, as if you finish it, and even if it’s in pencil it has a bigger effect on me than most of the computer animations.

PENISTON: Really? Yeah, so there’s still hope for drawing these days. Not an entirely lost art yet.

SWARTE: Oh no, not at all. I’m sure. What I see for instance, and even in architecture, they all try to represent their ideas in almost reality. But reality makes the viewers also anxious that all has been done, nothing can be changed any more. And that’s dangerous. In the beginning you have to make people enthusiastic about your ideas. So if you leave open something, they fill in with their own fantasy. And they have the idea that their own fantasy will be realized. And that helps a lot in the process.

THE FUTURE

THOMPSON: For the last 15, 20 years you seem mostly to do the few comics you do on commission: Someone approaches you. Like Little Lit, and the strip you were doing for the CD.

SWARTE: Yeah, that’s right. It’s mostly on commission. But that doesn’t bother me too much. If it is a comic or some other contracted project, you are sort of building your own labyrinth, what is possible within the limits, and whether it’s considered to be, and while you can give the labyrinth another form, it’s still a labyrinth, and you have to come out of it. And this process of coming out of it, that’s the fun.

THOMPSON: Of course. After all, the Sistine Chapel was commissioned, and, for that matter, presumably the Mona Lisa. But you don’t ever feel, “Gosh, I should I be doing more comics”?

SWARTE: Oh, yes, of course, because each year I visit the comic festival at Angoulême — and that’s not the only comics festival that I’m visiting — and each time I’m knocked out by many young, talented artists and how they tell their stories in comics. I mean, it’s such a rich medium that there is always a moment while visiting such a festival that I say to myself, “Why did I ever leave this rich medium? Why not sit behind a drawing table and make a lot of beautiful comics?”

Well, you never know how things evolve. Now that I’m 58 years old, it’s not a problem for me to travel, to negotiate with people, to have meetings, whether it be in Brussels or in Amsterdam. But there comes an age when you don’t travel that much any more, you prefer to stick behind your drawing table. Now, although you cannot say what the future brings you, I have the idea that there will come a moment where new comics come out of me.

THOMPSON: You look at someone like Will Eisner, who basically retired, and then in his retirement, decided, “I’m just going to sit down and do comics,” and he did.

SWARTE: Absolutely. And that was a wise decision.

David Peniston is an art instructor in Oakland, Calif.

Transcribed by Raymond Fleischmann, Kristy Valenti and Stephen Charles Hirsch.