This interview with Harlan Ellison was conducted in 1979, and it is therefore a time capsule to a different world of comics culture — and, I suppose, of everything else. Very little of it will make sense to someone who does not have an historical understanding of that moment in comics history.

I had been editing and publishing The Comics Journal for just three years and had, by 1979, found my — and the magazine’s — dissenting editorial voice. This dissent was aimed at what was then a monolithic Comics Industry composed primarily of Marvel and DC, which comprised what was then called the “mainstream” and which published probably 98% of the comics being consumed by the American public (excepting Archie, which was under everyone’s radar, especially mine); the other 2% were the vestiges of the underground comix publishers as well as a few minuscule independent or self-publishers: Eclipse published its first book in 1978 (written and drawn by two mainstream creators); Mike Friedrich’s Star*Reach (1974–79, preposterously touted as “ground-level comics” — to position itself between underground and mainstream comics — consisted mostly, again, of mainstream creators doing work not far removed from what they were already doing at Marvel and DC; P. Craig Russell’s Parsifal being an ambitious exception and deserving of recognition as such); and two self-publishers, WaRP Graphics (Richard and Wendi Pini’s Elfquest) and Aardvark-Vanaheim (Dave Sim’s Cerebus). Eisner’s A Contract With God (which gets a cameo mention here) appeared in 1978 and was considered something of an anomalous breakthrough.

Perhaps most importantly in this context was Byron Preiss’s Byron Preiss Visual Publications, which, in 1976, began releasing what would later be referred to as graphic novels with Tom Sutton’s Schlomo Raven (published through Pyramid Publications as Fiction Illustrated #1) — reaching its zenith with Howard Chaykin’s adaptation of Alfred Bester’s The Stars My Destination Volume 1 (published through Baronet Publishing Company) in 1978. But that was it. It was slim pickings for us aesthetes, but that was how barren and unpropitious the aesthetic landscape of comics was in 1979. There was almost nothing to discuss except Marvel/DC comics and almost nothing good to say about them.

The idea that comics creators were capable of genuine artistic expression on the same level as the film directors (Bergman) and literary writers (Doctorow, Borges) we talked about in this interview was considered ridiculous or beside the point when it was considered at all, which it generally wasn’t. There were no models for “literary comics,” no such thing as graphic novels. Comics were the lowest common denominator entertainment form, and not even a mass medium any more — ignored by the general public, disdained or ignored by the intelligent reading public, and beneath the notice of reviewers and critics. Even Ellison, who boasted of his elitism and thought of himself as the elitist’s elitist, didn’t think comics as a medium could —or should— be anything more than junk. “I think anybody who takes comics seriously as an adult is already pretty far gone,” he said in this interview. “I can’t take them that seriously. When we talk about mediocrity, I say, ‘Yeah, but they were always mediocre.’”

That was the reality I was trying to buck at the time, and the only way I knew to do that was by engaging in a full-scale frontal assault on the comics industry in every issue of the Journal. One of the reasons I interviewed Ellison is because he was known for his full-scale frontal assaults.

Actually, that is revisionism on my part, now that I think about it. When I arrived at the midtown Manhattan apartment Ellison was staying at, I had no idea what to expect or what I would come away with. The original impetus for the interview was a review I had published panning a collection of comics adaptations of his short stories called The Illustrated Ellison (published, again, by Byron Preiss), which elicited a screaming phone call from Ellison.

I suggested that we record an interview where he could address what he considered the review’s shortcomings and critical inaccuracies. He agreed to meet me the next time he came east. I probably also wanted to interview him because he was familiar with and loved comics but traveled professionally in circles outside of comics; because he was not beholden to the corporate interests that controlled comics production and thus could speak more freely; and because he was notoriously outspoken about his high aesthetic standards.

The interview began about 9:00 p.m. and lasted until about 3:00 a.m. As it turned out, we both spoke freely — in the opinions of many working professionals at the time, too freely — often crossing the line into tasteless disparagement of good professionals and of the values of professionalism generally.

People who were not yet born when this interview was conducted have told me that today’s young generation may well be horrified by it. Maybe so. But I believed then, and I believe now, that it was a necessary corrective to the institutionalized complacency, sterility, and code of silence that had at that time settled upon the comics industry like a shroud.

Although one can see the seeds of Ellison’s public displays of fatuity to come — his incongruous obeisance to Stan Lee, for example — I still think this was a necessary interview for its era and that Ellison was the right voice in the right place at the right time — in The Comics Journal in 1979.

— Gary Groth, July 3, 2018

From the introduction to the 2006 reprint from The Comics Journal Library Vol. 6: The Writers by Tom Spurgeon:

The writer and essayist Harlan Ellison has written few comic books, but his presence among comics writers of the 1960s, 1970s, and 1980s is impossible to dismiss. Not only did he befriend several of the writers featured in this volume, he paid attention to their work and provided an example of a sometimes-scriptwriter, sometimes-prose author career that many no doubt aspired to. Ellison also cut an intriguing figure in the then-closely related field of science fiction, with a strong, forceful personality and a tendency to speak bluntly and to the point.

The following interview with Harlan Ellison by Comics Journal editor Gary Groth was a milestone in comics culture. It rambles mercilessly, careening from science fiction to literature to television to movies, but does so in a way that reminds how much comics at that time struggled with an artistic identity in a period where it had become clear that art wasn’t highly valued in any medium. Consider it a prediction of comics’ own movie boardroom dramas and outrageous behavior to come.

Ellison, as a famously contentious writer and critic — but one who didn’t always want to apply stronger standards to comics — provided an interesting model for and contrast to the more demanding attitudes of comics fans who, in increasing numbers, were continuing to read the medium into adulthood.

Comments within this interview led to a lawsuit by writer Michael Fleisher against both the interviewee, the interviewer, and the interviewer’s publisher. The defendants won in court, but the Ellison-Fantagraphics relationship was soured forever.

The interview begins in the middle of a discussion, featuring arguments that in many ways began early in the history of comics and continues today, even if the identity of the speakers have changed. [As the tape begins, Ellison is discussing then-current comic book writers.]

This interview originally appeared in The Comics Journal #53, Winter 1980.

HARLAN ELLISON: Dennis [O’Neil] has got the fatal flaw that I think is shared by many of these fellows. They pick the wrong idols. They worship at the wrong altars. When you’re a kid and you pick for your idol Jonas Salk or Charles Lindbergh or Babe Ruth, then you’ve really got something to shoot for. When you pick for your idol Jack Kirby — I mean, as nice a man as Jack is, he’s a comics artist. He’s top of his profession, but it’s a very rarefied kind of thing, and even Jack has finally gotten out of it, into other artistic areas. But there’s a thing about your dreams when you’re a kid… In some way — I don’t know how — [Mike] Friedrich and Denny [O’Neil] and [Steve] Gerber and all of those guys got burned out in their brains. They worshiped the idols of childhood and never made the transition when they became adults to understand that success is having the dreams you had as a child but in adult terms. If when you were a kid you wanted to be a cowboy, you grew up and became a rancher — you don’t become a cowboy. If you wanted to be Superman, you grew up and became a pro football player — I mean, that’s as close as you’re going to get in this life to being Superman.

Dennis is one of the nicest and finest people I’ve ever known — I’d like to think he’s a very dear and close friend — and I really weep about it sometimes, I mean not really weep, but it makes me very sad to think about it because Denny could have been anything. Could have been anything. He’s got one novel to his credit, not a good one. Dennis had the ability to really go to the top of the mountain, and you say, “Why didn’t he? What the hell’s he doing at Marvel, and what the hell was he doing at DC for 10 years?” I wish to Christ he were out of comics. I wish to Christ he were writing things that…

GARY GROTH: I have a feeling he does, too.

ELLISON: Yeah. I mean, he did a piece for — was it Oui, or Penthouse?

GROTH: The one on Vaughn Bodé?

ELLISON: No… it was a piece in New York magazine. It was very good; he really is a fine writer. I mean, God only knows whether he’ll ever be Dostoevsky, but a lot of years and a lot of visceral material has to be expended behind the typewriter before you can ever hope to be read five minutes after you’re down the hole. And Dennis has spent a lot of time writing a lot of stuff that even at its best — and Dennis to my mind is the best writer that’s come out of comics in the last 30 years.

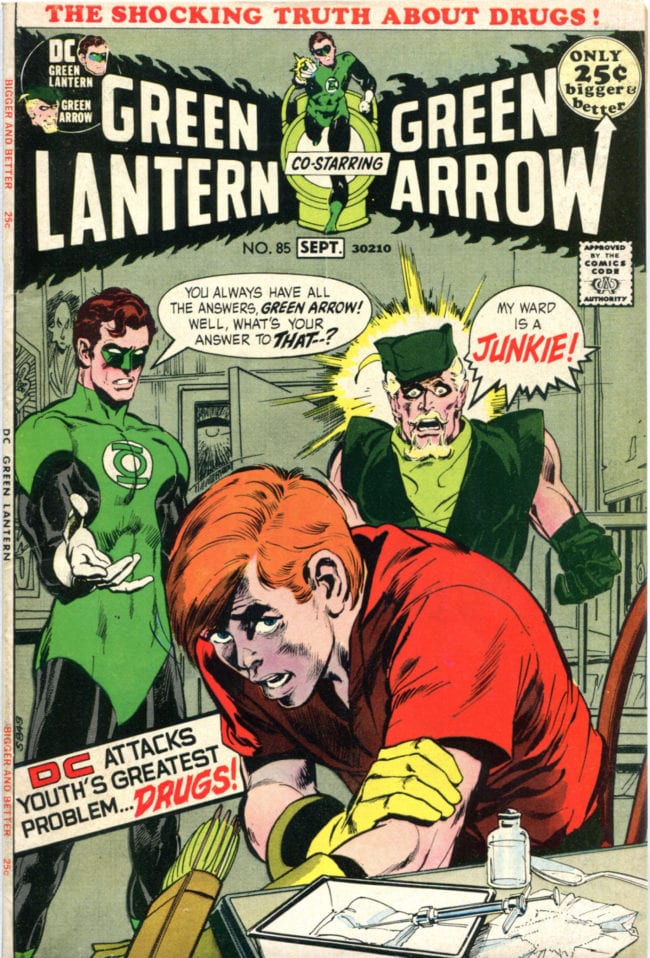

The stuff he did for Batman in the ’60s, man, the Green Lantern/Green Arrow stuff, was important stuff. He and Len Wein are the two best writers that I have ever read in comics. The best. Len doing Swamp Thing and Denny doing Batman and Green Lantern; that was heaven. That was a time to read the comics, for Chrissake — what a leaping, boundless joy. Pick up the crap today, man, I just — psheeeww. I mean, it’s silly. And the best you can hope for is less silly.

GROTH: Wouldn’t you say that most of the writers in comics have more or less reached their proper position in life in a way?

ELLISON: Yeah, I suppose. That’s a tragic thing. I know a lot of them.

GROTH: I’m not talking about Denny. I’m talking about others.

ELLISON: Right. There are some guys — I mean, I have no doubt that Len Wein and Marv Wolfman will be out of that in a few years, will be into something else.

GROTH: Really?

ELLISON: Absolutely. I think they’re too good. I mean, I’m more familiar with Len’s writing than with Marv’s, but I recently met Marv again. I had met him briefly before, but he and Len came out to the house and hung out and shot some pool and went and had a funny dinner and all. They’re lovely guys, and I think their aspirations are higher, and I think they’re good hustlers. A good hustler is not going to stay in a little pond if he has access to a bigger one. They’re already packaging these novels for Pocket Books, so they’re in an entrepreneurial configuration, if you’ll pardon the jingoism, already, and I think they’re going to go on from there. I really think they’re going to become less writers and more entrepreneurs of some sort. I don’t know how… Time is very strange. I mean, the first time I met Gerry Conway, who the hell would’ve known that Gerry Conway would single-handedly ruin the entire comics industry. He’s a classic example of the deification of no-talent in all industries. He’s not good, but he has it in on Thursday. And that’s all they care about. You know, fill them pages.

GROTH: That kind of attitude seems to pervade almost all popular entertainment — television, comic books, even book publishing.

ELLISON: Absolutely. They’ve got endless hours of prime time to fill, and they don’t care what they fill it with, because the drones in this country will sit and watch it, and they don’t give a shit whether they’re watching The Merry Wives of Windsor or Charlie’s Angels; they see it all as one and the same thing. And that’s one of the reasons taste in this country has almost totally vanished. There is no sense of discrimination. Good and bad alike are lauded and they applaud garbage on the grounds of, “Well, it was entertaining.” And they suddenly raise to the level of deification absolutely mindless and empty posturing poseur-kind of stuff like Coming Home and Heaven Can Wait and Black Sunday and Manhattan, all of which are really empty, pointless, silly, stupid movies. And a film like Apocalypse Now, which is breathtaking, a genuine work of high art, is treated as if it’s some kind of brobdingagian freak because it took so long to make. They don’t understand that high art occasionally takes time to perfect, that you cannot constantly have the script written by Thursday, that you cannot constantly have 64 pages of bright, fresh, and intelligent comic-book story written by Thursday, that high art demands clean hands and composure, as Balzac said.

When I was much younger, when I was just starting to write, I had a lot of respect for writers who could get it in on time, and then suddenly I realized, “Wait a minute, what the hell is this, ‘Get it in on time?'” I owe no allegiance to publishers or producers or networks. Even if they paid me staggering sums of money, I owe allegiance only to the work. Only to the work. And if I give them shit on time, then I have cheated them. If I take six months longer than they expected, or five years, or 10 years longer, and give them something that no one else could have given them, then I’ve honored the obligation to them. Whether they see it that way or not, that’s the way I see it. I’ve become totally irresponsible in that respect.

People say, “When is The Last Dangerous Visions coming out?” and I give them the same answer that Michelangelo gave to the Pope: “It’ll be done when it’s done.” And of course they scream and they yell, and Fred Pohl runs around and tells terrible stories about me. Fred Pohl was running around at SeaCon and telling everybody that The Last Dangerous Visions wasn’t going to come out because everybody was withdrawing their stories. People were pulling their stories left and right. Fred is an old acquaintance and periodically we have been very good friends, and I tell you, for the record, in no uncertain terms, Fred Pohl is full of shit right up to his earlobes. Not one single writer has pulled a story from The Last Dangerous Visions. Nobody — no one has pulled a story from The Last Dangerous Visions. Every single story that I had for the book is there. It’s going to be in very soon, in a month or two, and it’ll be done.

It’s been a huge job writing over 100,000 words of introductions because the book is 750,000 words; it’s 120 stories. It’s a three-volume boxed set. It’s the biggest anthology ever done, of any kind — it’ll certainly be the biggest science fiction anthology — and it’s the final block in that edifice called Dangerous Visions and it’s state of the art. It’s bloody state of the art. Somebody says, [in an idiot’s voice] “How can it be state of the art? Some of the stories you bought ten years ago.” Doesn’t matter. Doesn’t matter. It’s still state of the art today. It’s where it is, as far as I can tell, now. Because things have been kind of laying low, they haven’t done much in the last five or six years. There are a lot of new writers, and I’ve gotten those as they came along. I don’t know why Fred would say a thing like that. I mean, he may be mistaken, he may have been being funny, he may even be malicious, who the hell knows? All I know is that the book is going to press exactly with the table of contents that I had all along. The only story that was removed was one I removed a while ago from a writer who gave me a hard time, so I said “Fuck you,” took the story out and gave it back to him, because he was playing Mr. Moneybags. He’d had one little successful thing happen to him and all of a sudden he thought his shit didn’t stink, and he started siccing agents on me. And I said, “Hey, man, fuck you! Here’s the story, keep the advance I gave you, piss off! You know, roll it up and insert it up your tozz!” And I got a substitute story of exactly the same length from P.J. Plauger, and it’s a very very fine story, and the book’s the same length. It was just that one thing. But it had nothing to do with everybody pulling for any reason. Everybody’s stuck by me; they understand.

And I’ve had a tough year anyhow. I spent an entire year, from November of the year before last to last November, writing I, Robot for Warner Brothers. It was a full year; it just fucked up my health, fucked up all my relationships. The woman I was going with just one day wandered up into my office and said, “Forget it! I didn’t sign on for this!” I’d gone days without washing, without brushing my teeth, without shaving. I was like an animal. She would make me lunch and I’d come down and eat it with my hands and grunt at her and then go back to the typewriter. It was monstrous. I was like some sort of crazed vampire bat who would come out in the dead of night to suck up dinner and babble meaningless lunacies at her and then crawl on all fours through broken glass back to the typewriter. And this went on for day after day after week after month after… for a full year. I finally got it all finished, handed it in to Warner Brothers.

They said, “It’s a work of genius” — that’s a direct quote — “it’s a work of genius, it’s brilliant… we’d like a few changes.” So I passed on that, I wouldn’t do the rewrites, so they took me off it and gave it to four other writers in the last 10 months. A week ago they crawled back on their knees and said, “Would you go back on the script and do it?” I said, “If you stay out of my way. Get out of my fuckin’ face and then I’ll do it.” They said, “Uhh, I was waiting for you to say, ‘I told you so.’” And I said, “I don’t have to tell you ‘I told you so,’ asshole. I was right to begin with. You don’t pay me $150,000 to write a goddamn movie that you couldn’t get made in 15 years and I do it and you tell me I have to change this character for this, and this character for that.” I said, “We’re not going to change Susan Calvin into Rocky just so the assholes who sit in these four-in-one theaters can applaud. Fuck the assholes, man. If they don’t like it, let them go see another Smokey and the Bear movie — Smokey and the Bandit,” whatever the hell it is.

I’m getting crankier in my old age. Have you noticed that?

GROTH: I thought you were mellowing until now.

ELLISON: I did too. I swear to God, just one day I’d like to get up and not be angry. Just one goddamn day in this life I’d like to arise and not be fuckin’ pissed off at the world.

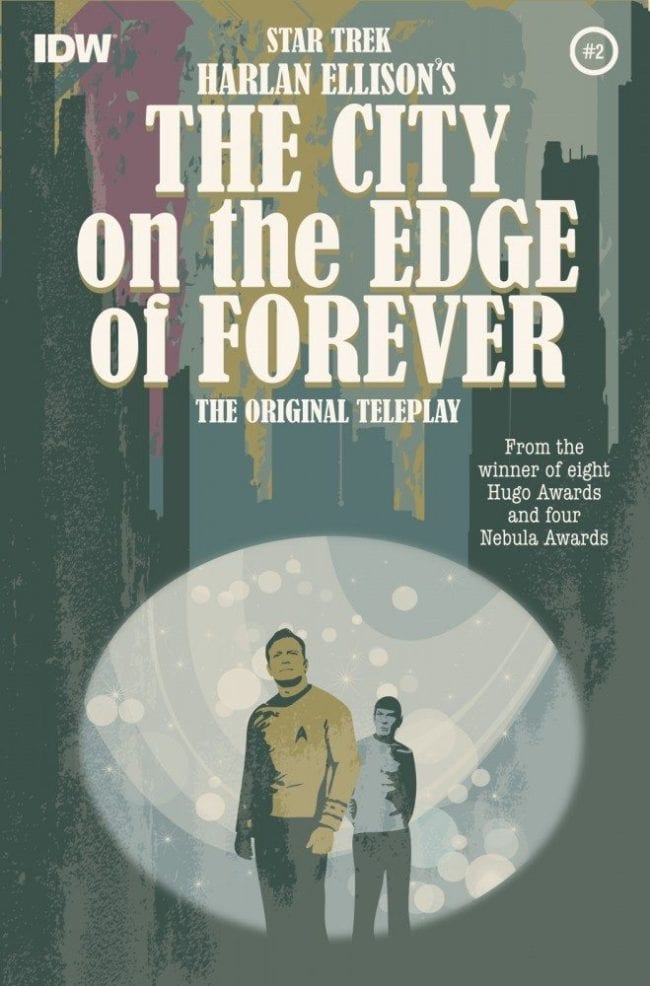

I spent an entire day today in deposition. I’m suing ABC-TV and Paramount for three million dollars. The lawsuit was filed two years ago; we’re going to trial. We’ve got pre-trial hearings on October 25, we’ll probably be in the courts in December. They ripped off my “Brillo” story and teleplay, which I did for ABC, and was then shown to NBC, to a guy who is an executive at NBC, who then went to Paramount and put together Future Cop and sold it back to the same people who had rejected “Brillo” at ABC!! And we got them on access, and… The sum total of their case is that “Ellison’s hands aren’t clean, because “Brillo” — the story I had in Analog, with Ben Bova — Ellison stole the idea from The Caves of Steel by Isaac Asimov.” Now, anyone who’s ever read both of those damn things will know how berserk that whole thing is. I mean, even the suggestion that I would steal from Isaac, who has been one of my closest friends for 25 years — I mean, you don’t steal from your friends. And if I were going to steal, I would really have to be some kind of a great schmuck to steal from a book like The Caves of Steel, that everybody in the world has read, right?

But what happened was… I mean, they don’t even know from Caves of Steel. What happened was, those putzhole attorneys, “Ahh, we’ve got a nuisance suit here.” It’s not a nuisance suit; I promise you, it’s not a nuisance suit. I’m going to have those fuckers’ hides on the wall and I’m going to drive it through their brains.

So they said, “We’ve got to find an expert on this and find out about Ellison.” So they go to somebody who works at ABC, somebody who’s a Trekkie, and they say, “What do you know about Harlan Ellison?” “Ohhh, Harlan is a terrible man, he insults Star Trek people, and the first time he met Isaac Asimov he insulted him, ohh, he’s terrible.” They said, “Well, do you know the story 'Brillo'?” “No.” “Well, then go read 'Brillo'.” So the person goes and reads “Brillo” and they say, “Well, is there anything else like this in science fiction?” and he says, “Well, there was a robot in Caves of Steel.” “Caves of Steel, okay, let’s write that down.” So they say that I stole “Brillo”, Ben Bova and I — Ben Bova, are you ready for this, the ex-editor of Analog, the fiction editor of Omni, stole from Isaac Asimov. That’s wonderful; I love that.

So they say I stole “Brillo”, which was published in the August 1970 issue of Analog from three sources: from The Caves of Steel, which I read when I was 15 years old in 1953 — or however the hell old I was then — and I didn’t even think of it when we did “Brillo”. I also stole it from David Gerrold’s book When Harlie Was One, which, strangely enough, was published three years after “Brillo.” But I clearly saw into the future, and I saw that book and I said, “Aha!” And the third book is Michael Crichton’s The Terminal Man, which doesn’t even have a robot in it, but why deal with logic here — which also, oddly enough, was published four years after “Brillo”. Now these schmucks are so stupid that they don’t even go and look up the fuckin’ publication dates on these things, and they bring this stuff into deposition and I sit there and I giggle at them! They’re such dummies! But arrogant, because they’ve got a big insurance company behind them and they figure they’re going to paper me out — that’s what they call it in the law industry — they’re going to paper me out with depositions and discovery and all that bullshit. It’s already cost me over $36,000 and it will probably cost me another 35 or 40 [thousand] before it’s finished but I’m going to get ’em!

GROTH: By “papering you out” do you mean that they hope you can’t afford to fight it?

ELLISON: Right, exactly. The attorney’s fees are going to kill me, and they’re going to depose this person and they’re going to depose that person and they’re going to take all these depositions and I’m going to have to pay for all that, and blablablablablablah, and they don’t understand. They don’t understand, man. I’m a snapping turtle. When I fasten, I’m on, I’m on to the grave with my teeth in their throat. They don’t understand that. They think it’s money. They already tried to settle. They tried $165,000, whatever the fuck it was they offered, and I said, “Put it up your snout! I don’t want it! Forget it!” The money is only to make them hurt a little. What I want is public admission. See, they don’t understand what ethics are. They steal out there constantly from writers and very few writers can afford to have the chutzpah to fight them. I can do it because I’m untouchable. Nobody can write like me. They’ve gotta hire me. I don’t worry about that. If they don’t hire me, fuck ’em. I do my books. I make a lot of money and I’m safe, man. And even if they fuckin’ blacklisted me and killed me in the publishing industry — I don’t write TV anymore anyhow — but in every industry, I can go back to being a bricklayer. I mean. I’ve still got my ticket. And if they broke my hands, for Chrissake, I could sing on the street for dimes. They cannot scare me and they cannot… The worst they can do is kill me.

GROTH: By “they,” you mean the television networks, the executives?

ELLISON: Yeah, yeah. The great military-industrial complex. You know, “them” out there. And if somebody reads this, he’s going to say, “Ho ho ho-o, has this poor fucker gotten paranoid.” No, I’m not paranoid, I just know that industries and corporations and machines like the movie studios, huge, giant corporations that are owned by conglomerates are no longer human beings. They are mechanical things that are run by insurance companies and fidelity reserves, corporations, and things like that, who have insured them, and they say, “This is a nuisance suit.” They don’t know… They don’t have the common sense to say, “Jesus Christ, we did steal this. Let’s take care of this with this guy.” And I would settle tomorrow for the attorney’s fees and time that I’ve spent — reimbursement for that and for Ben to get a chunk of change — for public admission, and I mean big public admission, not a line at the bottom of a newspaper. I want a full-page ad in Variety, I want a full-page ad in Hollywood Reporter: “We had our hands in this man’s pocket and he caught us cold. We stole from him and he made us pay for it. Signed, the President of Paramount Pictures, the President of NBC Television Network.”

And I want a billboard on Sunset Boulevard. I want that. They won’t give me that, of course. I mean, they’ll give me all the money in the world because money is what they give you to shut you up. They can afford to give money to you. What is it to them? It’s another drop in the bucket. But boy, they won’t give you the admission, and that’s what I’m going to take them to court for.

GROTH: Is this kind of casual theft that goes on malevolence, or ignorance, or stupidity, or what?

ELLISON: Arrogant stupidity is the base of it. First of all, they do not understand that it is wrong to steal. A man like Glen Larceny does not understand that it is bad to rip off Smokey and the Bandit and do BJ and the Bear. It is wrong to rip off Butch Cassidy and the Sundance Kid and do Alias Smith and Jones. It is wrong to rip off Star Wars and do Battlestar Ponderosa. It is wrong to do these things. He does not understand this. He says [in cloddish accent], “Wu-ull, it’s a viable idea.” That’s the wrong use of the word “viable,” but that’s the kind of language a jerk like him uses. They don’t understand.

I once had a meeting with a producer for a film, and he said, “I’ve got a terrific idea for a movie. You remember the giant ant movie? Well, we’ve got a whole new terrific idea: it’s a giant grasshopper,” and he goes on, to tell me about the giant grasshopper and I say to him, “That won’t work.” He says, “Why? Why? Why not?” I said, “There’s something called the Inverse Cube Law” — Square-Cube Law, whatever the hell it’s called — “as the mass grows, the weight grows, and a grasshopper has hollow bones, and it will collapse under its own weight. So you can’t have it, it won’t work.” “Oh, oh, oh, that’s all right, we’ve got a lot of other ideas, I’ve got a lot of ideas over there,” and he pointed to a stack of old science-fiction magazines. He said, “Pick any one of those! Take any one of those!” I said, “Those belong to writers, those are stories you have to buy.” “Why? Why? They’re just ideas!” They simply don’t understand. Now, the people who are at the networks, who are in charge of creative…

I mean, the things I’m hearing at these depositions are terrifying to me. We’ve been taking depositions from people at the highest levels at Paramount and ABC. One guy, who was in charge of creative development for the entire ABC network, his entire credential for being in that job was that he had gone to business college and had graduated and had been the executive assistant to the chairman of the board of RB Furniture. Now you say, how does a man like this wind up telling me what to write? How does this happen? Well, it’s because businessmen can talk to businessmen. They don’t trust artists. And they have producers who have been artists of one kind or another on a very low level, guys like Glen Larceny, are the interface. They are the axemen. They are the whistlers who come in between you and the merchants. And they get you to write this shit and they corrupt you and writers are turned into more hacks. I won’t do it anymore, but there are plenty who… Almost everybody in comics, every, one of them would give his arm to be able to go out there and write shit. They’re dying to do it. There are guys like… I’ve brought out a couple of guys on my own.

GROTH: The usual excuse is that they’ll make a lot of money and then they can get out.

ELLISON: Yeah. But they don’t, of course. You know, I’m firmly convinced that writing shit is like eating bad food. Eventually, you will be unable to eat good food. You write shit long enough and it will corrupt your talent if you have any. There are guys who’ve got very minimal talents and it doesn’t matter whether they corrupt it or not. I could name them and would happily name them, but why bother? There’s no sense kicking cripples. I mean, all you have to do is open up comic books from Marvel and DC and take a look at them. You see these guys have a very minor-league talent and to say, “Well, these people are wasting their talent” is ridiculous. I mean, they’re never going to be any better. What’s the name of the guy who used to do… over at Marvel… he used to do… [Pause]… the worst artist in the field.

GROTH: Don Heck?

ELLISON: Don Heck. [Laughter.]

GROTH: This is going to look good.

ELLISON: Well, of course. You say, “Who’s the worst artist in comics?” “Don Heck!” Of course. Absolutely.

GROTH: I’ll tell you a true story: A very high-positioned editor at DC told me three weeks ago that he respected Don Heck very much.

ELLISON: Because he turned in the work on time? Of course. That does not deserve respect. I mean, a dray mule can do that. You know, for whatever other flaws and faults Neal Adams has, and God knows he has many — he’s driven almost everybody bugfuck at one time or another — Neal is an artist, and Neal is conscientious and Neal cares, and when they rush him Neal turns out dreck and he hates it and he hates himself for it because he has the soul of an artist and he’s been a seminal influence and he’s a man capable of good work. Jeff Jones was driven away, Bernie Wrightson was driven away, Barry Smith was driven away, [Michael] Kaluta was driven away. All the really good guys, they vanished. They couldn’t take it anymore. And of course, the industry says, “Well, man, they were irresponsible.” Irresponsible is what the fuckin’ river merchants call artists who will not kowtow to artificial fuckin’ deadlines. That’s what they call them — irresponsible, crazy, hard to deal with, impossible. Five thousand Don Hecks are not worth one Neal Adams. And I don’t know Don Heck. I’m not even sure I’ve ever met Don Heck, and I mean him no harm when I say this. I’m talking about his work, talking about what I see on the page. Who was that guy who did Nova? Was that Heck?

GROTH: No.

ELLISON: That was Ayers?

GROTH: Wolfman wrote it, and who the hell drew that? I don’t know. It was awful.

ELLISON: Awful! Wasn’t it Heck?

GROTH: Dick Ayers or someone.

ELLISON: Yeah, it was somebody like Dick Ayers. It may have been Dick Ayers.

[The artist in question was Sal Buscema.]

GROTH: It’s all the same.

ELLISON: Yeah. And even guys like Gene Colan. There’s a man who had an interesting talent — on time, on time, on time — and he pissed it away.

GROTH: Gene Colan and Don Heck: Isn’t it just a matter of Colan having a little more talent but being totally unwilling to channel that talent in any meaningful direction? I mean, Colan’s the better illustrator, but that’s about all.

ELLISON: Yeah, well, that’s what I say, there’s a genuine talent there which he’s never done anything with. He got to a place and he did a thing and that’s all he did. And it’s like Neil Simon. People talk about how great a playwright Neil Simon is. Neil Simon bites the big one. He’s the worst fuckin’ playwright put on this planet. He writes cheap, shallow shit. He found himself a niche and he can do it and he can do it facilely and he does it and that’s what’s happened to Gene Colan.

The secret is what is the secret of all great art, I believe, which is taking risks, running into the mouth of the fire, walking the tightrope, trying the thing that nobody. Even if you fail dismally, goddammit, that’s what it’s about. You can’t be safe. The minute you’re safe in what you’re doing, you are dead. You have stagnated. People write comments — well, they don’t do this anymore, I’ve taught them enough lessons — when I say “they,” I mean just the general audience, the mindless wad that’s out there. They didn’t pay any attention to me for a while, and then somehow I started making a lot of noise, and I did “Repent, Harlequin”. So it won a Hugo and won a Nebula.

They said, “Oh, wow, terrific story, terrific story.” So then I sat down, and my next story was “I Have No Mouth and I Must Scream”, and they said, “Ahh, what a piece of shit, man, why don’t you write something terrific like ‘Repent, Harlequin’, why don’t you do that again?” Well, then that won a Hugo and so then the following year I wrote “Pretty Maggie Moneyeyes”, and they said, “Oh, Christ, what garbage! Why don’t you do something like ‘I Have No Mouth and I Must Scream’? I mean, that was terrific!” I never go the same place twice. You may be able to detect things in my style that I enjoy doing, but I’m never… You can hit a sitting target. That’s why, when they imitate me — when people do parodies of my work, they’re parodies of things I wrote 10, 15 years ago, because they don’t know where I am today, man. I mean, “Jeffty Is Five” is not like anything I wrote 15 years ago, a completely different kind of story, and next year I’ll be somewhere different. But they don’t do that in comics. They just don’t do that. The last time risks were taken was in the ’60s. They did “relevance,” and most of that was bullshit because nobody really believed in it, except for guys like Denny and Len and a few others, who really came out of the streets.

GROTH: Wouldn’t you say, though, that if even Denny’s stuff, the GL/GA books, were written as a book, or in any other medium, it would be laughed at?

ELLISON: Oh, sure, it was very sophomoric, but that’s what comics are. Comics are sophomoric. I mean, even when they’re doing some kind of great experimental thing like “Weirdworld”, I mean, Jesus, what imbecile, childish, adolescent bullshit. That’s the kind of stuff I read in the public library in Painesville, Ohio when I was a ten-year-old child. You know, stories about fuzzy-footed little creatures. I mean, if that’s the big, bold new development in comics… and I’m sorry to say it to you because it was on the cover of your bloody magazine. The “Bold New Direction.” You ought to be ashamed of yourself, for Chrissake.

GROTH: Well, I think we were more impressed with the technological aspects of it. For what it is, I mean, it’s a little elf tale…

ELLISON: But it’s banal! It’s imitation! It’s bad, cheap, silly imitation Tolkien! And Tolkien is imbecile shit to begin with. And God knows how many letters you’ll get on that [high-pitched whine]: “How dare he speak nyeh nyeh nyeh….”

I was at the Second World Fantasy Convention and Michael Moorcock, who’s been a real close buddy of mine, was the guest of honor, and they expected Michael to say all the things they wanted him to say. He got up there and sat down and he proceeded to tell them what shit Tolkien was, that he hated Tolkien’s stuff, that he thought it was absolute dreck and garbage, and that if they wanted to read good fantasy, they ought to go and get Gormenghast, the Mervyn Peake trilogy, which is brilliant. I mean, that’s high art. And right next to me was a woman who suddenly leaped up and said [indignant woman’s voice:] “You’re a terrible man” — and this was not even a little old lady in varicose veins and support hose, this was a woman in her 20s or 30s who should have known better — “You’re a terrible man and they should never have made you guest of honor. You ought to be ashamed of yourself and you aren’t even fit to carry Tolkien’s typewriter,” his hernia case, or whatever the hell he has, and she ran out of the auditorium and people were applauding her and booing Michael. Now, this is a man who is considered a natural, national treasure. This is a man who has won the Guardian Prize, for Chrissake, which is the equivalent of the Pulitzer over here. This is a man who is mentioned in the same breath as Graham Greene and C.P. Snow and he understands literature and he says to all of these slobbering, bucolic, tunnel-visioned, terminal-acne fans, “You deify shit! You worship garbage!” As John Gardner said in his book On Moral Fiction, there is room in the world for trivial art, but it is only because high art exists and is recognized and is worshiped and honored that the world is safe for triviality. But in a world of nothing but triviality, there is nothing to anchor to, there is no place to look for a firm foundation, and as a consequence, you get worse and worse and worse and taste gets further and further bastardized. And none of these people will take the risk.

Let me tell you something: Jenette Kahn is a nice woman. I’ve met her a number of times and she’s a nice woman. One day, paging through a DC comic — and it had never dawned on me before, and I have been reading comics since I was a very little boy, I mean, I was Supersnipe, I had all the comics, man — I suddenly looked at an ad for Crossman rifles and I suddenly thought, “Oh my God — I’ve been looking at these all my life.” It was an apple exploding and when I looked at it, I didn’t see an apple, I saw a kid’s head. I said, “Holy shit! A kid with a BB gun could shoot an apple and explode it, and if he’s ever read William Tell he’s going to put it on the head of another kid.” And I said to myself, Wait a minute, the condition in this country of macho craziness, where we wind up honoring an asshole like John Wayne, a fascist eggsucker like that, comes out of this whole tradition of guns. And where do kids get their guns? They’re brought up with them in comic books. “Dad will buy me a Daisy.” I remember wanting a — I probably had one — a Ryder, a Daisy Red Ryder BB gun, and I said to myself, “This is terrible. This is terrible…”

And I wrote to Jenette Kahn and said, “I’m a member of the Ban the Handguns Coalition, and it just dawned on me, and I’m not sure if you’ve ever thought of this, but it is infinitely painful for me to see a medium that I have adored since I was a kid be used for the promulgation of this kind of bad thing.” I said, “Do you really need these ads this much? Couldn’t you, out of a spirit of social responsibility, say, ‘No more gun ads, no more war toys ads,’ and seek other kinds of ads?” God knows they’ve got plenty of them these days, they’ve got the television networks and the candy companies, and Grit, Burpee seeds, and all that good shit. She wrote me back a note and said, “I’m going to look into this,” and for a couple of months there were no gun ads and I thought, “My God, I have been a force for good in my time.” And then, of course, they started up again and I realized that it had just been a couple of months where there were no gun ads. They simply don’t give a shit. They have no corporate sense of social responsibility. And I’m not sure anyone has ever mentioned this in print before, but I hope that whoever reads this article will take it and stuff it under Jenette Kahn’s nose and say I’m aware of the fact she didn’t do anything about it. I’m aware of the fact that she probably went to the moneymen, and [greedy voice]: “Well, you know how many hundreds of thousands of dollars worth of ads they take in our comics over the years, blablablablah.” That’s always what it is — it’s the fat burghers who make the bucks, and they don’t give a shit what you put in the comic. They don’t give a damn.

GROTH: I assume you’re advocating this kind of moralizing only when it has to do with children. Do you feel similarly toward ads for pornography, or, I guess, guns in magazines like Esquire…?

ELLISON: Having been someone who has had a very violent life… I have guns around my house. They’re all locked up; I haven’t used them in years, for Chrissake. I used to go out and hunt predators, and I’ve shot gophers in my backyard. I mailed one of those to the comptroller of New American Library. He wouldn’t let me out of a contract so I sent him this dead gopher by fourth class mail.

GROTH: It must have taken three weeks to get there.

ELLISON: Oh, it was ripe. It was in bad shape. There was also a recipe for Dead Gopher Stew in the package, a Ted Cogswell recipe that was in Anne McCaffrey’s book, Cooking Out of This World. You’ve got a dead gopher that’s redolent and covered with maggots, you’ve got to do something with it, you can’t just let it go to waste, So-o-o…

I’ve never seen pornography ads in comics, but I’m against guns. I really am.

GROTH: Don’t you think that people should be able to make their own choices as far as what they see and buy?

ELLISON: Yeah…

GROTH: Be it stupid or otherwise…

ELLISON: I suppose I do…

GROTH: In other words, there’s a dilemma here.

ELLISON: Yeah, there’s a First Amendment dilemma and given a choice of censorship or letting the gun ads run, I would say, let the gun ads run. Let anything run. Don’t start thinking for other people. You can’t legislate morality. You just can’t. Ordinarily, when I hear people talking about [whining voice:] “Well, we can’t let pornography get into the hands of children”… I don’t know what children they’re talking about. You go past a high school, you look at 13-year-old girls, and they look like a casting call for Irma La Douce! There’s a young woman, just turned 17, who has been on my back to get in bed for months. I can’t get rid of her, and I keep telling her, no! I’m not one of those guys who’s a dirty old man who likes young girls. I’ve nothing to say to young girls…

GROTH: Send her to Roman Polanski.

ELLISON: Whatever, yeah… He’s a creep. We were talking about protecting children. Most people who talk about protecting children are just a bunch of goddamn anal-retentive bluenoses who are terrified of sex themselves and are also terrified that someone else is going to have a good time. So I don’t make that brief on pornography, because I’m not really sure what pornography is. I really think I would blanch to put a copy of Hustler in the hands of a 10-year-old kid, but then, what the hell is it going to hurt? I mean, aside from the brutality in Hustler — the bit-off nipples, and the penises guillotined and the blood and shit like that, and the debasement of women and the debasement of men, too, the feces-humor — that’s really in terrible, tacky taste, but that’s not going to hurt a kid’s mind any more than my mind was hurt from seeing Dick Tracy serials when I was a kid. I mean, shit, I was brought up on all that stuff and I turned out to be a very moral and ethical person who is “against that kind of thing.”

But I think it cannot hurt if you have a series of options, if you can take an ad for candy or you can take an ad for kites or you can take an ad for any damn thing, for clothing, anything you can take an ad for, and God knows they’ve got very sharp advertising departments, both at Marvel and at DC — I mean, DC is Warner, and they’ve got a lot of clout, they’ve got a big, big sales force and they can go and say, “Okay, let’s start exploring some other areas.” I think it demonstrates a lack of social responsibility. I think there are some things in our culture that are basically destructive and negative in tone and one of them is this whole “We should be able to bear arms” bullshit, which is as sick and twisted to me as the taboos against homosexuality. They’ve just discovered, according to Tripp’s book, The Male Mystique, or The Human Matrix, or something like that…

GROTH: The Homosexual Matrix.

ELLISON: The Homosexual Matrix, that there is more homosexuality in societies where there is a taboo against it than in societies where there’s not a taboo against it. In societies that don’t give a shit, people seek their own level and do what they want to do. And there’s always the Anita Bryants of the world who want to govern for us. And if I sound at all like that by saying that I’m pissed off about gun ads, I really don’t mean to.

GROTH: The reason I bring up this point is because the New York Times proved their great moral responsibility by refusing to accept porno ads.

ELLISON: Yeah, and they run ads for Nestlé, who are poisoning babies all over three different continents, and they run ads, without checking out verifications, for shyster car dealers and fast scam artists. This whole high moral tone that people affect strikes me as an enormous pain in the tuchis. All it is is a leftover from the Puritan ethic, which was nothing more than a hand-me-down from Torquemada anyhow.

GROTH: How would you describe your own moral tone?

ELLISON: I have no moral tone. I have an incredibly high ethical tone, but no moral tone at all. I would fuck chickens in the window of Bloomingdale’s if I felt like it.

GROTH: How would you differentiate ethics and morals?

ELLISON: Well, every time I’ve tried to do that, someone says to me, “Well, that’s a very fuzzy definition,” and it probably is. Ethics is to me… I’m trying to give you a for-instance, to explain what I mean, and I can’t even do that. For morals, I say fucking chickens in the window of Bloomingdale’s, but for ethics, I guess I mean…

GROTH: Would you say ethics is more of a universal standard and morals are society’s conventions?

ELLISON: Yeah. That’s very good. You’re a wiser man than I, because I would not have been smart enough to think of that, but that’s what I mean. I know it is ethically correct for me to defy the war in Vietnam, to go to jail. Now people say, “Well, that’s your moral conscience.” Maybe it is, but I consider that ethics. It is ethical for me to take the vast sums of royalties that have come in from the Dangerous Visions books over the last 12 years and make sure that every single penny goes out to those writers. It is ethical for me to fight ABC and Paramount, not just for myself, and not to make the buck. If tomorrow they said, “We’ll give the public admission so that other writers can see what we did, and all we’re going to do is pay your attorney’s fees and you’re not going to make one penny off it,” I’d go for it. I’d go for it in a hot second. They won’t. They’ll never do that, but that would be a very ethical act for me. That whole thing I did with the ERA in Arizona, that’s ethics. It’s a sense of belonging to the community of humanity and knowing that you have a responsibility, and not just to yourself, to make yourself feel good and to get the best for yourself, but if you’ve got any kind of strength and any kind of clout and any kind of courage, to fight for other people, goddammit.

I tell you this in strict seriousness, in dead seriousness, in earnest seriousness, in serious seriousness:

People say, “How do you see yourself?” And I finally figured out how I see myself. I see myself as a cross between Jiminy Cricket and Zorro. That’s me, man. In my wildest dreams, I see myself precisely that way. I’m able to do a lot of fighting for a lot of people because I’m known as a pain in the ass…

For instance, Mystery Writers of America has for years had their MWA anthologies, to which MWA writers are supposed to contribute their stories. The money goes all to MWA, usually to put on a banquet and pay the office staff in New York. I got very pissed off at that. I said, “Wait a minute! How dare an organization that’s supposed to be a service organization for writers screw writers out of the money for their work?!” “Well, it’s tradition…” “Don’t give me tradition. I don’t want to know tradition, man; that fucks over writers. I don’t want to hear that.” And I made a big stink. Finally, they took it to the board of directors of MWA and said, “Oh, Ellison’s making noise again, he’s screaming and yelling,” and one guy on the board, one guy, Otto Penzler, who is the mystery editor at Gregg Press and publisher of The Armchair Detective and has got the Mysterious Bookshop here in New York — he’s a very good man, we’re friends — he said, “Dammit, Ellison is right. He’s right. Science Fiction Writers of America, they pay their writers for the stories that go into the Nebula Awards book every year. Why aren’t we paying our people? Even if it’s just an honorarium?” So they’re paying some ridiculously incredible stipend like $15, $25, but it’s a breakthrough. And of course the Board of Directors has taken all the credit for it: “We’ve decided that it’s not right…” Right? Nobody remembers and nobody will acknowledge that it was this deranged, crazed loon from Los Angeles who screamed in their ears and said, “Goddammit, do this.” And that’s okay. When the great book is written, they will say, “This little fucker did a lot of good.” And that’s okay because I know what I do. And that’s fine.

I’ve got a reputation for being a terrible man and a brutal, ruthless, rotten human being. A woman I know said, “I was afraid to meet you. I heard you brutalized women.” I said, “I do, I do… you know, I beat them with big sticks, I tear out their eyeballs, I embed them in walls — I’m a rotten human being. A rotten human being.” The stories they tell about me serve a very good and very worthwhile end. I love ’em, man. I love to hear the crazed mythology that comes back to me. I love it when they say I threw somebody down an elevator shaft — and they believe it! They believe it!

ELLIOT BROWN: Did you really punch Irwin Allen in the face on the top of the table?

ELLISON: No! I never touched Irwin Allen! It was the head of ABC Network Continuity that I punched. Irwin Allen was just sitting to the right. Yeah, well, that’s absolutely true. And actually, I would have kicked him in the face. See, I didn’t mean to punch him in the face, I meant to kick him in the face, but I ran down this table and it was a 10-foot-long table and it had been highly polished and I slipped and fell and I slid on my stomach and when I came at this guy I hit him and caught him in the mouth and he went over backwards and fell off his chair and this model of the Seaview fell off the wall and broke his pelvis. That’s what happened.

GROTH: Since this has been brought up, can you tell us why you punched this guy out?

ELLISON: Yeah. They did an article about it in TV Guide a few years ago. It was a man named Adrian Samish who was at that time the head of ABC Network Continuity, which is the censors. He was a gibbering gargoyle who was a failed advertising man, a failed college man, and a failed homosexual — he couldn’t even make it in that area — and they put him in as head of censors and he came on at a story conference for my script for Voyage to the Bottom of the Sea and insisted that I make a lot of stupid changes. And I said, “Those are stupid! And you’re stupid for asking for those things. I mean, I don’t know who you are, but I’m a writer. I have no idea what you are!” But I wouldn’t make those changes, and he says, “You’ll make them all right.” And I said, “No, you don’t understand, I will not make them.” And he said, “Writers are toadies. You’ll do as you’re told.” And I went bananas.

We were at this long conference table in Irwin Allen’s conference room. Irwin was to the right of me and there were 26 yes-men all up and down. I jumped up on my chair because it was the quickest way to get to him. It was a narrow room and everybody had their chairs back, and their chairs forward, and I would have had to go around them and I saw blood red and I wanted him then. I didn’t want to have to go around anything, so I just took the straightest route, which was right down the middle of the fuckin’ table. There were papers and everything, and I slipped on them and went right on my gut and just slee-ee-ee-id down the length of the table and as I approached him it was like one of those Alfred Hitchcock dolly-in shots and POWWW! I tagged him a good one right in the pudding trough and zap pow over he went, ass-over-teakettle, windmilling backwards, and fell down and hit the wall and Irwin had this big, six-foot long model of the Seaview, which I guess they had used as a miniature on the series, and it came off its brackets and dropped on top of him and just busted this dude’s pelvis.

GROTH: It sounds like a Road Runner cartoon.

ELLISON: Yeah, that’s exactly what it was. It was a Road Runner cartoon. And I went for him. I was still going, hanging half off the table, my ass on the table. I’m swinging and I can’t quite reach him, and three guys grab me and drag me into another room, and I’m doing an adagio. You know, Lemme at ’im! I’ll eat the fucker’s eyeballs! I’ll tear out his heart! I’ll spit in the milk of his mother! Piss on him and the snake he slithered in on! I was crazed. They put me down on a chair, you know, “Take it easy, take it easy.” Oh, he was going to sue Irwin, he was going to sue me, he was going to sue 20th Century Fox. Irwin settled out of court; I don’t know how much he gave him, but he settled out of court on the thing.

Anyhow, yeah, so that kind of thing does happen, but I’ve never thrown anybody down an elevator shaft. And no one ever stops to say, “Well, wait a minute. Is the body still down there? Who was this guy? Didn’t his family worry about what had happened to him? And if Ellison threw someone down an elevator shaft, isn’t that murder? Wouldn’t the police be here investigating?” I mean, they never stop to think about these things. I sat in a room where they didn’t know I was there and somebody was having them tell Ellison stories and I heard guys lie and say, “Well, this is a true story because I was there and saw it happen. Ellison dropped a chandelier on 200 people at a convention in San Diego.” You know what happens if you drop a chandelier on people? They die. They die. There are a lot of people who go to hospitals. Jesus. But see, it’s good…

GROTH: It promotes you, right?

ELLISON: No, it’s not the promotion. I’m not worried about the promotion. That kind of promotion doesn’t do diddly squat. That’s not going to make any one of my stories any better. In the final analysis of the work, that kind of promotion is only good if you want to do TV talk shows.

GROTH: But the work doesn’t sell it. I mean, it’s the promotion that sells it, isn’t it?

ELLISON: Well, no. You see, there are 200 paperbacks that come out a month. You have exactly 14 days — that’s the lifetime of a paperback on the newsstand unless you’re Harold Robbins or Jaws, and I’m not. Which means that my audience is an audience that comes to me and to my work because they like my work. My books have never been promoted. Have you ever seen an ad for one of my books anywhere? Except maybe in science-fiction specialty magazines?

GROTH: No.

ELLISON: No. There was not one single ad taken for Strange Wine in the paperback edition. Warner Brothers brought it out and took not one single ad. And yet the book sells very well. To whom does it sell? It sells to people who know my name and read my work. Now even if I was the most colorful fuckin’ character in the world they wouldn’t come back to read a bad book from a bad writer. You don’t do that. You just don’t go back. So it’s the quality of the work that eventually sells it. Because I’m a word-of-mouth, underground writer, really. I won’t be that two years from now, I promise you. There’s something in the offing. Two years from now, I will be on the top of the best-seller list, and everybody will know the name and everybody will buy the book. Every asshole who reads under a hairdryer or while sitting with a can of beer in his hand is going to be buying and reading the book that I will be writing, the novel that I’m writing and that will be top of the best-seller list. I promise you. Number one best-seller in the nation. God knows how long it will be there, but it will be the number one fiction best-seller in the nation. Your brow is furrowing and you’re saying, “This man is really out of his mind with egomania.”

GROTH: Do you have this planned?

ELLISON: It’s planned to be… I mean, I’m not going to write it any less than I write anything else I write. I write one way: I write for me. But the book that I’m writing is a natural best-seller idea. It’s got to be a runaway. I mean, it’s such a simple, terrific idea you say, “Oh Christ, why didn’t I think of that? Why didn’t anyone think of that?” I thought of it. And I’m going to write it.

GROTH: It’s possible to reconcile best-sellerdom with art?

ELLISON: I think so. Lolita was a best-seller. The World According to Garp is flawed, but it’s a good book. Ragtime was a best-seller and a brilliant piece of work. Sometimes it happens. Sometimes it slips through. I ain’t gonna write a Peter Benchley kind of book, I ain’t gonna write Jacqueline Susann or Erich Segal or Sidney Sheldon; I mean, I’d rather cut off my hands than do that. But it’s a contemporary novel.

GROTH: Could you verbalize the difference in values between Ragtime and Harold Robbins or Jacqueline Susann? I mean, it sounds like a sophomoric question, but I think it might be important to…

ELLISON: It’s hardly a sophomoric question. It’s just that it’s a very difficult question to answer in any kind of codifiable terms.

GROTH: I know. That’s why I asked it.

ELLISON: I think… You see, they all say, “We-e-ell, you know, Harold Robbins, Jacqueline Susann, Erich Segal, it’s just to entertain.” Well, that’s what they said about Star Wars. That’s how they validate Star Wars, that’s how they validate Moonraker, that’s how they validate Charlie’s Angels — it’s just entertainment as if intelligence and entertainment could be separated. And so as a consequence, the word “entertainment” has come to be bastardized and to mean the cheapest, lowest possible common-denominator of entertainment. I find Kafka vastly entertaining. Shakespeare is entertaining to me. Not high-minded and uplifting; it’s entertaining. I mean, I can read Shakespeare and just laugh or cry or feel morose or feel great angst — I am touched by it. Because great art does that: It touches you and reaches you on an absolutely human level. And I think that the difference between a book like Ragtime or One Day in the Life of Ivan Denisovitch, or anything else that had been a best-seller that one can say has a claim to art, is that apart from being high-minded, as opposed to cheaply entertaining, to appeal to the lowest common denominator of entertainment, there is an artistic sensibility at work that speaks to the human condition, that in some way uplifts and enriches. We should come away from the work better than when we went to it. Whereas books like Harold Robbins’s and Irving Wallace’s and people like that are anti-human. They deny humanity. They postulate templates, clichés, cheap, ready-made answers to human emotions. They’re like an old-time Western; they’re black and white in some ways. And they are, for that reason, negative. They are anti-human. Does that answer your question?

GROTH: Yeah. I think that’s a good answer.

ELLISON: I’m not sure I’ve ever said that before, because I’m not sure I ever thought about it in those terms, so you probably have some…

GROTH: It’s a difficult thing to make concrete.

ELLISON: And it also sounds very pompous, and yet Ragtime is a very bright book, and funny, and light, and yet it…

GROTH: That wasn’t one of his best books, though, was it?

ELLISON: I am in awe of Ragtime.

GROTH: Really?

ELLISON: Yeah. I think Ragtime is one of the most important books of the last quarter century. That book is an amazing tightrope walk. It’s strictly and severely plotted and has so many things going for it. It’s a watershed work in terms of using real history and real people and weaving them in and out. It’s a fantasy. Very few people realize that it’s pure fantasy. I’m knocked out by that book. I mean, I like Welcome to Hard Times and… uh…

GROTH: Book of Daniel.

ELLISON: Book of Daniel, but Ragtime really blew me away. I read it, I think, about six or seven times.

GROTH: Let me follow up on some of the things you talked about. One is this wretched condition in which we live, where the most trivial, vapid crap is glorified as entertainment. How do you think we have reached this state of affairs?

ELLISON: It has always been so. It has ever been so. At the highest peak of the Roman civilization, bread and circuses were their entertainment. The popular entertainment was throwing Christians to Protestants, or whatever they threw them to, and legalized prostitution, the public brothels, and bear-baiting.

What I’m about to say will not fall well on the ears of many people. We, in this country particularly, have always totemized the Common Man, which I’ve talked about endlessly in my essays. This nebulous concept of a noble savage who will always in the last ticking moment rush up and say, “You cannot lynch that man! It’s not the Amurrican way!” and take him down, when in fact the Common Man has always been the slobbering, no-nose, prognathous-jawed, slope-browed yeti that formed those lynch mobs. And the Adlai Stevensons of the world and the Isaac Asimovs of the world and the Jonas Salks and the Ralph Naders and Florence Nightingales of the world have been in the minority. As I say, this will not fall lightly or happily on the ears of a lot of people. I deny the nobility and honor of the Common Man. I think to be common is to be base. I think it is closer to the animal state than to be uplifted and noble. I think that I’m clearly an elitist and that has always been the worst thing you can call someone. I mean, you can call someone an incestuous child-raper and it is less offensive to the monkey mass than being called an elitist, because what it says is, “I’m better than you.” And there are people who are clearly better than the rest.

No one can convince me that Albert Einstein was not better than everyone around him when he was alive. Clearly, Galileo — better! Clearly, Jesus — better! Better because brighter, quicker, faster, stronger, more able to think properly, inventively. Louis Pasteur said, “Chance favors the prepared mind.” These are the people who move the world. These are the people who risk it all and who usually condemned and driven mad by it and are usually killed by it, crucified in one way or another. Driven to the madhouses, as Dylan Thomas said. And they are the ones who move us, micromillimeter by micromillimeter, off dead center, who push us into the future to, one hopes, a better world. The mass always, if left to its own devices either because of genetics or situation, will go for ease and comfort and non-involvement and non-responsibility.

Why is it, for instance, that so many women in urban areas these days are clearly going bugfuck? Women, as I perceive them today, are more irrational than they have ever been. You know why? Because for the first time in the history of this planet, they have demanded for themselves a kind of equality that is not only just their right — it is due them, it is long overdue them — but accompanying it comes a concomitant responsibility for their lives and because they have for thousands of years not borne that responsibility for their lives in the way that they’re asking of themselves and their sisters, they are going crazy. Why is there such a rise in cigarette smoking among women? The rise in cancer among women is something like 200 percent in the last five years. It’s because they are more nervous; they are edgier. All the old templates have been broken. This kind of responsibility that we ask of people, to live in a better world, to make it a better world, to be more responsible, to stop driving cars, to stop paving over the world, to stop chopping down trees to provide paper for attorneys so they can do more and more briefs. That’s the thing that drives me crazy about this lawsuit. I see the amount of paper they’re using. Fuckin’ acres of woodland are going into this. They do everything in five or six Xerox copies. They make a mistake, they throw it in the wastebasket; they don’t even turn it over and use it for scrap paper. It drives me mad. Do you know that one hundred acres of timberland is used every year to make McDonald’s wrappings? One hundred acres. It’s a terrifying thought.

Anyhow, to tie off that thought, the monkey mass, the wad, the great sleeping wad, all it wants is to be comfortable and fat. All it wants is its television and its car and it doesn’t want to be infringed upon. It resents the gas crunch only because it can’t have off-road dune buggies to tear up the land and get out in the woods and start fires with their fuckin’ campfires and be as fat and happy as they’ve always wanted to be. The pursuits of intellect, the pursuits of the godlike state, are beyond them, and to them go all of these joys and treasures. Not just in literature, but in television, in cinema, in terms of fast-food chains that have pushed good dining out the window. Kids are brought up now to believe that a good meal is to go to McDonald’s. And they push and shove at Mommy and Daddy and Mommy and Daddy justify it to themselves by saying [in whining housewife’s voice]: “Well, you know, they’re very nutritious meals. I couldn’t give them this nutritious a meal at home.” What do you mean, you can’t give them this nutritious a meal at home? What the fuck are you doing all day that you can’t give them a nutritious meal, Mommy and Daddy?

GROTH: Let me ask you this: What do we do with the stupid people, the people who are too dense to learn?

ELLISON: What do you do with the stupid people?

GROTH: Yeah.

ELLISON: They’re in the majority. We don’t do anything with them. We just kind of skulk around ourselves in the deep grass and hope that they don’t spot us and kill us. It’s the green-monkey syndrome. You take a monkey that’s lived in a cage with all these other monkeys for years, and you take him out and spray him with vegetable color, you spray him green, and they’ll tear him to pieces within moments when you put him back in. They hate us. I’ve said these things on television and they’ve gotten thousands of telegrams and letters saying, “Who the fuck does he think he is?” Well, I’ll tell you who I think I am, schmuck: I’m the guy who’da run Anita Bryant out of town, that’s who the fuck I am. I wouldn’t keep her from working, but I sure as shit wouldn’t let a crazed loon like that get a foothold and infringe on other people’s rights. You don’t do anything with the stupid people. You just hope to Christ they don’t kill you before you’ve lived out your tenscore and seven, or sevenscore and 10, or whatever it is. Ninescore and four. [Giggles.]

GROTH: Is the reason for our wretched state of culture that there are too many stupid people who refuse to learn and refuse to upgrade their lives? These two facts seem woven together.

ELLISON: Well, they are, they’re inextricably linked. But you see, it’s almost impossible to try and blame them for their stupidity because they’ve been programmed that way. I mean, we are taught to be cowards all our lives. They start teaching it to you in kindergarten: “Don’t stick your head out above the crowd, you won’t be well-liked, the kids won’t play with you.” You’re taught to be liked. Well-liked and secure are the two things that you’re taught are the highest possible goals you can have. To be on the football team, to get in a fraternity, to get that piece of paper that will get you a job, to get into the organization, to rise in the organization, to get two cars in the garage and 2.6 children and a house in the valley, and these are the things that you’re taught and they’re drummed into your head in every possible conscious and unconscious way, through full-color lithography and phosphor-dot television, and subtle pressures put on you by church and school and family. Your parents, God love them, run these numbers back at you because these are the values that were instilled in them. God forbid you grow a beard and say, “I want to publish a comics fanzine.” They say, “Ahh, he’s a bum, he’s a bum. Why doesn’t he get a nice job as a bagger at the Safeway?” Those are the same people who would drive past on the freeway and not stop when someone’s lying there bleeding. They’re the same people who — what was it, 10 kids got on a bus here in New York and robbed 65 people on the bus. By the time the cops got there, there were only four people left on the bus and nobody wanted to get involved. You bow down to that kind of thing, man, and they will enslave you! Because the outlaws are always there and they don’t give a shit.

GROTH: “The Whimper of Whipped Dogs”.

ELLISON: Yeah, exactly. You either become a willing supplicant at the altar of street violence and brutality and dehumanization, or they eat you alive. You have no other choice! There’s my choice, which is to fight back, and they do you no honor for it. Because it makes them nervous. As long as they don’t have — and when I say “they,” I mean the monkey mass, the wad, you know, the scuttlefish — as long as they don’t have before them a living example of courage they can con themselves into believing that cowardice is discretion, is judicious behavior, is the better part of valor.

GROTH: As a critic, a television critic, do you feel a responsibility to teach, or do you write to those people who are already enlightened?

ELLISON: I don’t know the answer to that. I’ve wondered about that, too. I’ve done all the TV work I’m ever going to do. I don’t write for TV anymore, nor will I ever again. They cannot buy me, there’s no amount of money they can offer me, there’s no inducement, either. They can’t say to me, “Yeah, but gee, you’ll put something good on,” because my belief is, it doesn’t matter what’s on. It’s the medium that drives you crazy. As long as it’s on, you’re watching it, you’re a passive clone sitting there and letting this shit seep into your brain. The better the stuff is that they put in, the more intriguing it is and the more people will sit and watch it and the more they’ll turn into Jukes and Kallikaks and illiterate babbling boobs. And I don’t want any part of that. As for my criticism, I did two full books; I did the column [“The Glass Teat”] for two and a half years. It’s a massive compendium of everything I could say about TV. If you can’t say everything you’ve got to say about TV in two and a half years, you shouldn’t have started in the first place. The books are constantly being reprinted, The Glass Teat and The Other Glass Teat are being taught in universities in this country along, in the media classes — media classes, whatever the fuck that means, “Media,” another one of those babble-words…

GROTH: Dreadful-sounding. I took them in college; they’re dreadful things.

ELLISON: Psychobabble. They talk about, “Yes, television is a fine media.” [Laughter.] And I say, “No, you simp, it’s called ‘medium.’ ‘Medium’ is the singular.”

GROTH: There are two corrections to be made in that sentence. “Fine media…”

ELLISON: [Chuckles.] Yeah, well, it’s mutually contradictory. Well, in any case, they just reprinted the introduction to my book, Strange Wine, which is my most recent statement about TV, in which I said many of the things I’ve said here. It’s called, “Revealed! At Last! What Killed the Dinosaurs! And You Don’t Look Too Terrific Yourself!” And it’s all about how TV is turning us into a nation of illiterates and with statistics to prove it. I mean, this is no longer even up for grabs anymore; it’s not even in contention. We’ve had TV for 40 years now. We know what it does to people. We know what it does to children. We know what it does to the social order. For the first time in the history of the planet, we have a universal curriculum. The child in Beirut and the child in Bayou, New Jersey both get the same picture of the young, the old, the rich, the poor, men, women. I mean, once you start working with templates and clichés, everything blands out, and there is no room for the individual anymore. When there is no room for the individuals, you do not get the Jonas Salks, you do not get the Ralph Naders, you do not get the Wilbur and Orville Wrights, you do not get the Mary Wollstonecraft Shelleys. You don’t get those anymore. Or if you do, they die young.

So they reprinted it in the newsletter of the Television Critics’ Association. Well, the shit-rain fell, m’friends. Because these suckers make their living off that. I mean, they suck at — the neck of this hideous goblin, television, this behemoth that bestrides the land. And they cannot face that they are pimps and whores for a basically destructive force. They cannot face it. And so they will offer all of these off-the-wall and absolutely irrelevant reasons why TV is good or why it’s worthwhile, or the worst delusion of all, [pompous voice] “Well, I’m helping to change it by writing relevant crit-icisum,” which is about as valid as the schmuck who works in the mail room at NBC saying, “Ah’m gonna change it from within.” I lied to myself that way for years so I could make the money, and then one day I couldn’t lie to myself anymore. I said, “This is fuckin’ evil! I can’t be a party to this!” I get really messianic about it. It’s about as close to religion as I come. So it is not the fault of these people, because it is comfortable to be stupid. It is comfortable to be cowardly…

GROTH: Stupid people are happy.

ELLISON: I’m not sure about that. I’ve got another theory. I’ve heard all my life: “Ignorance is bliss.” I’ve got another theory. Here we go; fresh theory: I think that human beings are all basically the same, the smart ones, the dumb ones, me, you. I’m the same as the poor devil living in a slat-back shack in the redneck mountains in Virginia. I’m the same as he. But I know why I’m unhappy. They’ve got the same angst; the world is crushing them too. They’ve got to pay bad taxes, they get bellyaches from bad food, their children are getting fucked up and they don’t know how they can’t find any enrichment, their marriages are going bad, they long for and hunger for better things, they don’t know the nature of these better things, they don’t know who they want to be. They’ve tried to live the way their fathers and grandfathers and forefathers lived and it doesn’t work anymore, because it’s a different world. There’s a guy out there with a button. He can push the button at any time. They don’t understand why it is they’re dying from black lung, they don’t understand why it is their children are born with two heads, they don’t understand that somebody put pollutant into the air in Tibet, which has now floated down to wherever the hell it is, Decatur, Georgia. But they know they’re not happy. There’s tremendous subliminal, subcutaneous unhappiness there. The difference is, they don’t know who’s doing it to them. They don’t know they’re being manipulated by television and by big corporations that want them to buy cereals with sugar in it and another new car that is worth maybe a thousand dollars and they’re buying it for 10 thousand dollars. They don’t understand the nature of dishonesty. They look at a schmuck like Ronald Reagan, and he tells them they’re unhappy. They say, “Yeah, I’m unhappy,” and he says, “Well, wait a minute, you know who’s making you unhappy?” It’s the Jews or the communists, or it’s the big business, or it’s the Democrats, or it’s Jimmy Carter. “Yeah! Yeah! That’s who’s making me unhappy!” They’ll take anybody. They don’t give a fuck.

But they’re no happier than we are. They’re no happier just because they’re stupid. They’re in pain too, for Chrissake — they’re human beings! They burn, they hurt, they bleed, they cry — they just don’t know where it comes from. They don’t know what to do to relieve it. So what they do is, they get drunk, they go to football games, they fuck each other’s wives and husbands, they drive fast on the highways. You’ve got it in New York — people who go to the goddamn New York Experience and Studio 54, they’re just as stupid as the slatback rednecks. The only difference between the dope in Paswell, Virginia and the dope in New York is that in Paswell, Virginia it comes out of the mouth of Ernest Angley and the PTL Club and the 700 Club and Billy Graham and Oral Roberts, you know, “Gimme a snake!” and here it’s coke. They dance ‘til they drop, and they fuck ‘til they’re blind if they can get it up, and this is high life to them. A big evening is being in the same room with Truman Capote, who’s ‘luded out…

GROTH: Did you read John Simon’s essay on TV?

ELLISON: No, where was that?

GROTH: It was in TV Guide. He bought his first TV, and he ended it by saying that it wasn’t a total loss because he could put plants and things on the TV set and he wouldn’t have to bend down to pick them up off of a night table.

ELLISON: Right, and all the stupid letters from the schmucks in Pittsburgh. You notice how the schmucks always write from Pittsburgh? (Whining nasal voice:) “Who the heck does he think he is, nyeh nyeh nyeh nyeh, just because he uses big words doesn’t mean he’s smarter than…” Yes it does, lady, it means he understands the English language. It’s a tool and he uses it well. I admire John Simon enormously. I think he’s one of the few people in the world who has standards that are high. And occasionally he’s wrong and occasionally he makes a fool of himself, but what the hell, he runs the risk, he really plays the tightrope act.

GROTH: He has the courage to do it.