For many criminals who managed to operate beyond the long reach of the law, the Spirit was a dead end. Still there is none of them... er... alive, that is... who knows that this outlaw is really Denny Colt, a young criminologist presumed dead by the public but who continues to assist society behind the mask of the Spirit. “That he operates out of Wildwood Cemetery, where he is supposed to be buried, is known only to Commissioner Dolan and his daughter, Ellen…

Will Eisner, The Spirit, December 1945

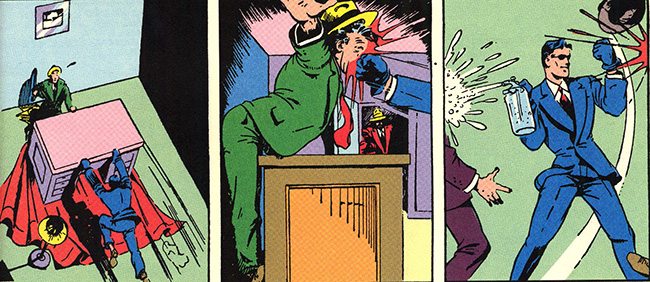

5. Fiction House put out Fight Comics, Planet Comics, Wing Comics; its one attempt at innovation was an outsized black-and-white book called Jumbo Comics — an unworkable hybrid of conventional comic book material and conventional newspaper material. Its single feature of interest was Hawk of the Seas, signed by Willis Rensie (Eisner spelled backwards). Hawk was a pirate feature, notably only as a trial run for The Spirit, full of the baroque angle shots that Eisner introduced to the business. Eisner had come to my attention a few years earlier doing a one-shot, black-and-white feature called ‘Muss Em Up’ Donovan in a comic book with the flop-oriented title of Centaur Funny Pages. ‘Muss ‘Em Up’ Donovan was a detective, fired from the force on charges of police brutality (his victims, evidently, were white). Donovan is called back to action by a city administration overly harassed by crime who feel it is time for an approach that circumvents the legalistic niceties of due process. Such administrations were in vogue in all comic books of the thirties and forties. The heroes they culled out of the darkness operated, masked or not, outside the reach of the law. Their job: to catch criminals operating outside the reach of the law. In theory, one would think a difficult identity problem — but as it turned out in practice, not really.

Heroes and readers jointly conspired to believe that the police were honest but inept; well-meaning, but dumb — except for good cops like Donovan, who were vicious. Arraignment was for sissies; a he-man wanted gore. Operating within the reach of the law a hero could get busted for that. So heroes, with the oblique consent of the power structure (“If you get into trouble, we can’t vouch for you”), wandered outside the reach of the law, pummeled everyone in sight, killed a slew of people — and brought honor back to Central City, back to Metropolis, back to Gotham.

‘Muss ‘Em Up’ Donovan was one such vigilante, a hawk-nosed, trench-coated primitive, bitter over his expulsion from office, but avid to answer the bell when duty once again called. Pages of violence: “Muss ‘Em Up’ beating the truth out of a sniveling progression of stoolies; Muss ‘Em Up’ kicking in doors; ‘Muss ‘Em Up’ shooting and getting shot at — a one-man guerilla war on crime. A grateful citizenry responded with vigor. ‘Muss ‘Em Up’ was reinstated — allowed to ‘Muss ‘Em Up’ in uniform once again. In those pre-civil-rights days, we thought of that as a happy ending.

Will Eisner was an early master of the German expressionist approach in comic books — the Fritz Lang school. ‘Muss ‘Em Up’ was full of dark shadows, creepy angle shots, graphic close-ups of violence and terror. Eisner’s world seemed more real than the world of other comic book men because it looked that much more like a movie. The underground terror of RKO prison pictures, of convicts rioting, or armored-car robberies, of Paul Muni or Henry Fonda not being allowed to go straight. The further films dug into the black fantasies of a depression generation the more they were labeled realism. Eisner retooled this mythic realism to his own uses: black fantasies on paper. Clothing sat on his characters heavily; when they bent an arm, deep folds sprang into action everywhere. When one Eisner character slugged another, a real fist hit real flesh. Violence was no externalized plot exercise; it was the gut of his style. Massive and indigestible, it curdled, lava-like, from the page.

Eisner moved on from Fiction House to land, finally, with the Quality Comics Group — the Warner Brothers of the business — creating the tone for their entire line: The Doll Man, Black Hawk, Uncle Sam, The Black Condor, The Ray, Espionage — starring Black-X — Eisner creations all. He’d draw a few episodes and abandoned the characters — bequeath them to Lou Fine, Reed Crandall, others. No matter. The Quality books bore his look, his layout, his way of telling a story. For Eisner did just about all of his own writing — a rarity in comic book men. His stories carried the same weight as his line, involving a reader, setting the terms, making the most unlikely of plot twists credible.

His high point was The Spirit, a comic book section created as a Sunday supplement for newspapers. It began in 1939 and ran, weekly, until 1942, when Eisner went into the army and had to surrender the strip to (the joke is unavoidable) a ghost.

Sartorially the Spirit was miles apart from other masked heroes. He didn’t wear tights, just a baggy blue business suit, a wide-brimmed blue hat that didn’t need blocking, and, for a disguise, a matching blue eye mask, drawn as if it were a skin graft. For some reason, he rarely wore socks — or if he did they were flesh-colored. I often wondered about that.

Just as Milton Caniff’s characters were identifiable by their perennial WASPish, upper middle-class look, so were Eisner’s identifiable by that look of just having got off the boat. The Spirit reeked of lower middle-class: his nose may have turned up, but we all knew he was Jewish.

What’s more, he had a sense of humor. Very few comic book characters did. Superman was strait-laced; Batman wisecracked, but was basically rigid; Captain Marvel had a touch of Lil’ Abner, but that was parody, not humor. Alone among mystery men the Spirit operated (for comic books) in a relatively mature world in which one took stands somewhat more complex than hitting or not hitting people. Violent it was — this was to remain Eisner’s stock in trade — but the Spirit’s violence often turned in on itself, proved nothing, became, simply, an existential exercise; part of somebody else’s game. The Spirit could even suffer defeat in the end: be outfoxed by a woman foe — stand there, his tongue making a dent in his cheek — charming in his boyish, Dennis O’Keefe way — a comment on the ultimate ineffectuality of even super-heroes. But, of course, once a hero turns that vulnerable he loses interest to both author and readers. The Spirit, through the years, became a figurehead, the chairman of the board, presiding over eight pages of other people’s stories. An inessential do-gooder, doing a walk-on on page 8, to tie up loose strings. A masked Mary Worth.

Not that he wasn’t virile. Much of the Spirit’s charm lay in his response to intense physical punishment. Hoodlums could slug him, shoot him, bend pipes over his head. The Spirit merely stuck his tongue in his cheek and beat the crap out of them — a more rational response than Batman’s, for all his preening. For Batman had to take off his rich idler’s street clothes, put on his Batshirt, his Batshorts, his Battights, his Batboots; buckle on his Batbelt full of secret potions and chemical explosives; tie on his Batcape; slip on his Batmask; climb in his Batmobile and go fight the Joker, who in one punch (defensively described by the author as maniacal) would knock him silly. Not so with the Spirit. It took a mob to pin him down and no maniacal punch ever took him out of a fight. Eisner was too good a writer for that sort of nonsense.

Eventually Eisner developed story lines that are perhaps best described as documentary fables — seemingly authentic when one reads them, but impossible, after the fact. There was the one about Hitler walking around in a Willy Lomanish middle world: subways rolling, Bronx girls chattering, street bums kicking him around. His purpose in coming to America: to explain himself, to be accepted as a nice guy, to be liked. Silly when you thought of it, but for eight pages, grimly convincing.

Or the man who was a million years old — whose exploits are being read about by two young archeologists of the future who discover, in mountain ruins, the tattered remains of an old Spirit pamphlet, which details his story: the story of the oldest man in the world, cursed to live forever for being evil, until on the top of a mountain, in combat with the Spirit, he plunges into the ocean and drowns. “Ridiculous story,” say those archeologists of the future as they finish the last page; these being their final words, for coming up behind them is that very old man, his staff raised high to crush their skulls, to toss them over the mountain edge into the ocean, and then to dance away, singing.

I collected Eisners and studied them fastidiously. And I wasn’t the only one. Alone among comic book men, Eisner was a cartoonist other cartoonists swiped from.

Foe to crime is the Hawk-man — Reincarnation of an ancient Egyptian warrior — Fighter against the strange forces that powerful criminals use. He fights the evil of the present with his collection of the weapons of the past!

The Hawkman, Flash Comics, January 1940

6. Swiping was and is a trade term in comic books for appropriating that which is Alex Raymond’s, Milton Caniff s, Hal Foster’s or any one of a number of other sources and making it one’s own. Good swiping is an art in itself. One can, for example, scan the first fifteen years of any National publication and catch an album of favorite Flash Gordon poses signed by dozens of different artists. Flash, Dale, Dr. Zarkov and Ming the Merciless stared nakedly out at the reader, their names changed, but looking no less like themselves even if the feature did call itself Hawkman. Other cartoonists preferred the Caniff touch, so next to nine pages of swiped Terry and the Pirates there often appeared nine pages of swiped Flash Gordon. Then there were those who mixed their pitches — using within the same story Alex Raymond swipes, Milton Caniff swipes, Hal Foster swipes, and movie-still swipes. So that a villain might subtly shift his appearance from Raymond’s Ming in one panel to Caniff s Captain Judas in another to Foster’s Sir Modred in a third to, at last, Basil Rathbone.

Swipes, if noticed, were accepted as part of comic book folklore. I have never heard a reader complain. Rather, I have heard swipe artists vigorously defended, one compared to another: who did the best Caniff, the closest Raymond? Hawkman, a special favorite of mine, gave an aged and blended look to its swipes — a sheen so formidable, I often preferred the swipe to the original, defended the artist on economic grounds (not everybody was rich enough to hire models like those big newspaper guys), and paid his swipes the final compliment of clipping and swiping them. On occasion, swipe artists would try to be clever, try to confuse the reader by including, within a single frame, a group of figures swiped — and even changed slightly — from three or four different sources. They may have gotten away with it with others, but never me: no comic book man could cloud the gray cells of the boy Poirot.

I not only clipped swipes, I traced and managed to get hold of their sources. I stapled them together, lay them in front of me and began my own chain of comic books. 64 pages in black-and-white pencil: Comic Caravan, Zoom Comics, Streak Comics. Each book contained an orthodox variety of super-heroes who, for their true identities, were given the orthodox assortment of prep school names: Wesley, Bruce, Jay, Gary, Oliver, Rodney, Greg, Carter — obviously the stuff out of which heroes are made —you didn’t find names like that in my neighborhood. I had a harder time with magicians because almost every name was taken. There was Mr. Mystic, and Merzah the Mystic, and Kardak the Mystic Magician, and Nadir Master of Magic, and Monako Prince of Magic, and Marvello the Monarch of Magicians, and Zambini the Miracle Man, and Ibis the Invincible, and Merlin the Magician, Yarko the Magician, Dakor the Magician, Zanzibar the Magician, Sargon the Sorceror, and Zatara.

I created a Spirit swipe (The Eel) and a Flash swipe (The Streak), a Lone Ranger swipe (The Masked Caballero) a Hawkman swipe (The Vulture) and even a Clip Carson swipe (Gunner Dixon: “Gunner Dixon is not meant to be a bold super athletic math genius who with his super powers turns to do good in this war-torn world — NO! He’s just an ordinary guy, he’s no mental giant, he can’t lick an army with his bare fist, but he can hold his own in any fight. All he is, is an American”).

Each story was signed by a pseudonym, except for the lead feature, which, star-conscious always, I assigned to my real name. I practiced my signature for hours. Inside a box; a circle; a palate. Inside a scroll that was chipped and aged, with a dagger sticking out of it which threw a long shadow. I had a Milton Caniff-style signature; an Alex Raymond; an Eisner (years later, when I went to work for Eisner, my first assignment was the signing of his name to The Spirit. I was immediately better at it than he was).

To me these men were heroes. The world they lived in, as I saw it in those years of idolatry, was a world in which a person was blessedly in control of his own existence: wrote what he wanted to write, drew it the way he wanted to draw it — and was, by definition, brilliant. And thus, loved by millions. It was a logical extension of my own world — except the results were a lot better. Instead of being little and consequently ridiculed for staying in the house all day and drawing pictures, one was big, and consequently canonized for staying in the house all day and drawing pictures. Instead of having no friends because one stayed in the house all day and drew pictures, one grew up and had millions of friends because one stayed in the house all day and drew pictures. Instead of being small and skinny with no muscles and no power because one stayed in the house all day and drew pictures, one grew up to be less small, less skinny, still perhaps with no muscles, but with lots of power: a friend of Presidents and board chairmen; an intimate of movie stars and ball players — all because one stayed in the house all day and drew pictures.

I swiped diligently from the swipers, drew 64 pages in two days, sometimes one day, stapled the product together, and took it out on the street where kids my age sat behind orange crates selling and trading comic books. Mine went for less because they weren’t real.

To advise a child not to read a comic book works only if you can explain to him your reasons. For example a ten-year-old girl from a cultivated and literate home asked me why I thought it was harmful to read Wonder Woman (a crime comic which we have found to be one of the most harmful). She saw in her home many good books and I took that as a starting point, explaining to her what good stories and novels are. “Supposing,” I told her, “you get used to eating sandwiches made with very strong seasonings, with onions and peppers and highly spiced mustard. You will lose your taste for simple bread and butter and for finer food. The same is true for reading strong comic books. If later on you want to read a good novel it may describe how a young boy and girl sit together and watch the rainfall. They talk about themselves and the pages of the book describe what their innermost little thoughts are. This is what is called literature. But you will never be able to appreciate that if in comic-book fashion you expect that at any minute someone will appear and pitch both of them out the window.” In this case the girl understood, and the advice worked.

Frederic Wertham, Seduction of the Innocent

7. Though I may have pirated the super-heroes I never went near their boy companions. I couldn’t stand boy companions. If the theory behind Robin the Boy Wonder, Roy the Superboy, The Sandman’s Sandy, The Shield’s Rusty, The Human Torch’s Toro, The Green Arrow’s Speedy was to give young readers a character with whom to identify, it failed dismally in my case. The super grown-ups were the ones I identified with. They were versions of me in the future. There was still time to prepare. But Robin the Boy Wonder was my own age. One need only look at him to see he could fight better, swing from a rope better, play ball better, eat better, and live better — for while I lived in the east Bronx, Robin lived in a mansion, and while I was trying, somehow, to please my mother — and getting it all wrong — Robin was rescuing Batman and getting the gold medals. He didn’t even have to live with his mother.

Robin wasn’t skinny. He had the build of a middleweight, the legs of a wrestler. He was obviously an “A” student, the center of every circle, the one picked for greatness in the crowd — God, how I hated him. You can imagine how pleased I was when, years later, I heard he was a fag.

In Seduction of the Innocent, psychiatrist Frederic Wertham writes of the relationship between Batman and Robin:

They constantly rescue each other from violent attacks by an unending number of enemies. The feeling is conveyed that we men must stick together because there are so many villainous creatures who have to be exterminated ... Sometimes Batman ends up in bed injured and young Robin is show sitting next to him. At home they lead an idyllic life. They are Bruce Wayne and ‘Dick’ Grayson. Bruce Wayne is described as a ‘socialite’ and the official relationship is that Dick is Bruce’s ward. They live in sumptuous quarters, with beautiful flowers in large vases... Batman is sometimes shown in a dressing gown ... It is a wish dream of two homosexuals living together.

For the personal reasons previously listed I’d be delighted to think Wertham right in his conjectures (at least in Robin’s case; Batman might have been duped), but conscience dictates otherwise: Batman and Robin were no more or less queer than were their youngish readers, many of whom palled around together, didn’t trust girls, played games that had lots of bodily contact, and from similar surface evidence were more or less queer. But this sort of case building is much too restrictive. In our society it is not only homosexuals who don’t like women. Almost no one does. Batman and Robin are merely a legitimate continuation of that misanthropic maleness that runs, unvaryingly, through every branch of American entertainment, high or low: literature, movies, comic books, or party jokes. The broad tone of our mass media has always been inbred, narcissistic, reactionary. Mocking Jews because most of the writers weren’t; mocking Negroes because all of the writers weren’t; denigrating women because all of the writers were either married or had mothers. Mass entertainment being engineered by men, it was natural that a primary target be women: who were fighting harder for their rights, evening the score, unsettling the traditional balance between the sexes. In a depression they were often able to find work where their men could not. They were clearly the enemy.

Wertham cites testimony taken from homosexuals to prove the secret kicks received from the knowledge that Batman and Robin were living together, going out together, adventuring together. But so were the Green Hornet and Kato (hmm — an oriental ... ) and the Lone Ranger and Tonto (Christ! An Indian!) — and so, for that matter, did Fred Astaire and Ginger Rogers hang around together an awful lot, but, God knows, I saw every one of their movies and it never occurred to me that were sleeping with each other. If homosexual fads were certain proof of that which will turn our young queer, then we should long ago have burned not just Batman books, but all Bette Davis, Joan Crawford, and Judy Garland movies.

Wertham goes on to point to Wonder Woman as the lesbian counterpart to Batman: “For boys, Wonder Woman is a frightening image. For girls she is a morbid ideal. Where Batman is antifeminine, the attractive Wonder Woman and her counterparts are definitely antimasculine.”

Well, I can’t comment on the image girls had of Wonder Woman. I never knew they read her — or any comic book. That girls had a preference for my brand of literature would have been more of a frightening image to me than any number of men being beaten up by Wonder Woman.

Whether Wonder Woman was a lesbian’s dream I do not know, but I know for a fact she was every Jewish boy’s unfantasied picture of the world as it really was. You mean men weren’t wicked and weak? You mean women weren’t badly taken advantage of? You mean women didn’t have to be stronger than men to survive in this world? Not in my house!

My problem with Wonder Woman was that I could never get myself to believe she was that good. For if she was as strong as they said, why wasn’t she tougher looking? Why wasn’t she bigger? Why was she so flat-chested? And why did I always feel that, whatever her vaunted Amazon power, she wouldn’t have lasted a round with Sheena, Queen of the Jungle?

No, Wonder Woman seemed like too much of a put-up job, a fixed comic strip — a product of group thinking rather than the individual inspiration that created Superman. It was obvious from the start that a bunch of men got together in a smoke-filled room and brain-stormed themselves a Super Lady. But nobody’s heart was in it. It was choppily written and dully drawn. I see now that my objection is just the opposite of Wertham’s: Wonder Woman wasn’t dykey enough. Her violence was too immaculate, never once boiling over into a little phantasmal sadism. Had they given us a Wonder Woman with balls — that would have been something for Dr. Wertham and the rest of us to wrestle with!

Rat-at-ta-tat! Rat-at-ta-tat! Hear that roll of a drum? Twee! Twee! Twee! Hear that shrill of a fife fit’s a call, brother — it’s a call to join the parade. You too, sister ... you’re in on this! Get in step! Get in step! For here they come! The butcher, the banker, housewife, school-kid! Everybody’s marching ... marching behind The Minute Man! $o buy tho$e war bond$! Buy tho$e war$tamp$! Get in step! Get in step with Batman and Robin as they go marching on to victory with ...

The Bond Wagon. Batman, Detective Comics, August 1943.

8. World War II was greeted by comic books with a display of public patriotism and a sigh of private relief. There is no telling what would have become of the super-heroes had they not been given a real enemy. Domestic crime-fighting had become a bore; one could sense our muscled wonder men growing restless in their protracted beatings up of bank robbers, gang overlords, mad scientists. Domestic affairs were dead as a gut issue: super-heroes wanted a hand in foreign policy. At first this switching of fronts seemed like a progressive political step — if only by default. Pre-war conspiracies had always been fomented by the left (enigmatically described as anarchists), who put it into the minds of otherwise sanguine workers to strike vital industries in order to benefit unidentified foreign powers. Now, with the advent of war it was no longer necessary to draw villains from a stockpile of swarthy ethnic minorities: there were the butch-haircutted Nazis to contend with — looking too much like distorted mirror images of the heroes, perhaps — but no less bold an innovation for the conceit that Anglo-Saxons, too, could be villains.

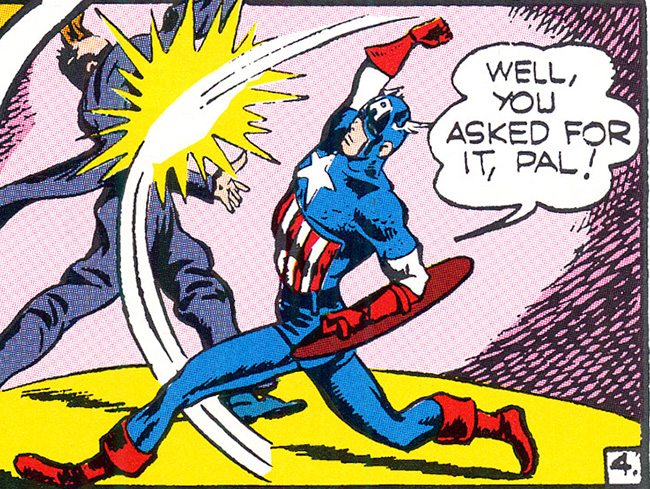

Consistent with the policy formalized by Chaplin’s Great Dictator, Hitler was never portrayed as anything but a clown. All other Germans were blond, spoke their native language with a thick accent, and were very, very stupid. The I.Q. of villains dropped markedly as the war progressed. Whatever there used to be of plot was replaced by action — great leaping gobs of it, breaking out of frames and splashing off the page. This was the golden age of violence — its two prime exponents: Joe Simon and Jack Kirby.

The team of Simon and Kirby brought anatomy back into comic books. Not that other artists didn’t draw well (the level of craftsmanship had risen alarmingly since I’d begun to compete), but no one could put quite as much anatomy into a hero as Simon and Kirby. Muscles stretched magically, foreshortened shockingly. Legs were never less than four feet apart when a punch was thrown. Every panel was a population explosion — casts of thousands: all fighting, leaping, falling, crawling. Not any of Eisner’s brooding violence for Simon and Kirby: that was too Liston-like. They peopled their panels with Cassius Clays — speed was the thing, rocking, uproarious speed. Blue Bolt, The Sandman, The Newsboy Legion, The Boy Commandoes and best of all: Captain America and Bucky. Like an Errol Flynn war movie. Almost always taken from secret files. Almost always preceded by the legend: “Now it can be told.”

But the unwritten success story of the war was the smash comeback of the oriental villain. He had faded badly for a few years, losing face to mad scientists — but now he was at the height of his glory. Until the war we always assumed he was Chinese. But now we knew what he was! A Jap; a Yellow-Belly Jap; a Jap-a-Nazi Rat: these being the three major classifications. He was younger than his wily forebear and far less subtle in his torture techniques (this was war!). He often sported fanged bicuspids and drooled a lot more than seemed necessary. (If you find the image hard to imagine I refer you to his more recent incarnation in magazines like Dell’s Jungle War Stories where it turns out he wasn’t Japanese at all: He was North Vietnamese. At the time of this book’s publication the wheel will, no doubt, have turned full circle and he’ll be back to Chinese.)

The war in comic books despite its early promise, its compulsive flag waving, its incessant admonitions to keep ‘em flying was, in the end, lost. From Superman on down the old heroes gave up a lot of their edge. As I was growing up they were growing tiresome: more garrulous than I remembered them in the old days, a little show-offy about their winning of the war. Superman, The Shield, Captain America and the rest competed cattily to be photographed with the President; to be officially thanked for selling bonds, or catching spies, or opening up the Second Front. The Spirit had been mutilated beyond recognition by a small army of ghosts; Captain Marvel had become a house joke; The Batman, shrill. Crime comics were coming in, nice art work by Charles Biro, but not my cup of tea. Too oppressive to my fantasies. Reluctantly I fished around for other reading matter, stumbled on Studs Lonigan — not exactly an example of Dr. Wertham’s boy and girl watching the rain fall while discussing their innermost thoughts, but still it was a novel. By the age of fifteen I had had it with comic books. I was not to read them again until I went into the business a year later.

Fear not, queen mother!

It was Laertes

And he shall die at my hands!

... Alas! I have been poisoned

And now I, too, go

To join my deceased father!

I too — I—AGGGRRRAA!

The Death Scene, Hamlet Comics

9. Had I only been six years older I could have been in comic books from almost the beginning: carting my sample case in the spring of 1939 instead of 1945; a black cardboard folio with inside overlapping side sheets, secured tight with black bows on its three unbound corners, containing fourteen by twenty-two inch pages of Bristol board on which could be drawn typical adventure swipes of the day, inked with as slick a Caniff line as one could evoke at sixteen — a series of thick and thin brush strokes wafted onto the paper with the lightest, most characterless of touches. Draftsmanship was not the point here — this was technique!

Going the rounds then: checking the inside glossy covers of comic books for names and addresses, riding the subway out of the Bronx in the morning rush, my portfolio on the deck, squeezed tightly between my legs so that the crowd could not bruise it, nor art thieves steal it. The bigger houses — so official looking — would have scared me, and then dismissed me for lack of experience. How are you supposed to get experience when no one will give you experience? The answer: to begin low — at one of the countless schlock houses grinding out the junk in small, brutal-looking offices all over town. These, the cheapie houses, were where one got the first breaks. Not being worth anything, no one else worth anything would hire you. But the schlock houses operated as way stations for both the beginners and the talentless.

Artists sat lumped in crowded rooms, knocking it out for the page rate. Penciling, inking, lettering in the balloons for $10 a page, sometime less; working from yellow typescripts which on the left described the action, on the right gave the dialogue. A decaying old radio, wallpapered with dirty humor, talked race results by the hour. Half-finished coffee containers turned old and petrified. The “editor,” who’d be in one office that week, another the next, working for companies that changed names as often as he changed jobs, sat at a desk or a drawing table — an always beefy man who, if he drew, did not do it well, making it that much more galling when he corrected your work and you knew he was right. His job was to check copy, check art, hand out assignments, pay the artists money when he had it, promise the artists money when he didn’t. Everyone got paid if he didn’t mind going back week after week. Everyone got paid if he didn’t mind occasionally pleading.

The schlock houses were the art schools of the business. Working blind but furiously, working from swipes, working from the advice of others who drew better because they were in the business two weeks longer, one, suddenly, learned how to draw. It happened in spurts. Nothing for a while: not being able to catch on, not being able to foreshorten correctly, or get perspectives straight or get the blacks to look right. Then suddenly: a break-through. One morning you can draw forty per cent better than you could when you quit the night before. Then, again you coast. Your critical abilities improve but your talent won’t. Nothing works. Despair. Then another breakthrough. Magically, it keeps happening. Soon it stops being magic, just becomes education.

I’d have met, in those early days, other young cartoonists. We’d talk nothing but shop. A new world; new super-heroes, new arch-villains. We’d compare swipes — and then, as our work improved, we’d disdain swipes. We’d joke about those who claimed no longer to use them but, secretly, still did. Sometimes, secretly, we still did too. Some of us would pair off, find rooms together — moving our drawing tables away from the family into the world of commercial togetherness. Eighteen hours a day of work. Sandwiches for breakfast, lunch, and dinner. An occasional beer, but not too often. And nothing any stronger. One dare not slow up.

We were a generation. We thought of ourselves the way the men who began movies must have. We were out to be splendid — somehow. In the meantime, we talked at our drawing tables about Caniff, Raymond, Foster. We argued over the importance of detail. Must every button on a suit be shown? Some argued yes. The magic realists of the business. Others argued no; what one wanted, after all, was effect. The expressionists of the business. Experiments in the use of angle shots were carried on. Arguments raged: Should angle shots be used for their own sake or for the sake of furthering the story? Everyone went back to study Citizen Kane. Rumors spread that Welles, himself, had read and learned from comic books! What a great business!

The work was relentless. Some men worked in bull pens during the day; free-lanced at night — a hard job to quit work at 5:30, go home and freelance till four in the morning, get up at eight and go to a job. And the weekends were the worst. A friend would call for help: He had contracted to put together a sixty-four page package over the weekend — a new book with new titles, new heroes— to be conceived, written, drawn, and delivered to the engraver between 6 o’clock Friday night and 8:30 Monday morning. The presses were reserved for nine.

Business was booming. New titles coming out by the day, too many of them drawn over a two-day weekend. Cartoonists throughout the city took their pencils, pens, brushes, and breadboards to apartments already crowded with drawing tables, fluorescent lamps, folding chairs, and crippling networks of extension cords. Writers banged out the scripts, handed them by the page to an available artist — one who was not penciling or inking his own page, or assisting on backgrounds on someone else’s. Jobs were divided and sub-divided — or sometimes, not divided at all. An artist might not work from a script, but write his own story, in which case it would be planned in pencil right on the finished page. Some artists penciled only the figures, leaving the backgrounds for another artist who then passed the page to a lettering man who then passed the page to an inker who then might ink only the figures, or sometimes only the heads, passing the work, then, to another inker who finished the bodies and the backgrounds. Everybody worked on everybody else’s jobs. The artist who contracted the job would usually take the lead feature. Other features were parceled out indiscriminately. No one cared too much. No one was competitive. They were all too busy.

If the place being used had a kitchen, black coffee was made and remade. If not, coffee and sandwiches were sent for — no matter the hour. In mid-town Manhattan something always had to be open. Except on Sundays. A man could look for hours before he found an open delicatessen. The other artists sat working, starving: some dozing over their breadboards, others stretching out for a nap on the floor, their empty fingers twitching to the rhythm of the brush. During heavy snow storms stores that stayed open were hard to find. A food forager I know of returned to the loft rented for the occasion, a loft devoid of kitchen, stove, hot plate, utensils, plates or can opener, with two dozen eggs and a can of beans. Desperate with rage and hunger and the need to get back to the job, the artists scraped tiles off the bathroom wall, built the tiles into a small oven, set fire to old scripts, heated the beans in the can (which was opened by hammering door keys into it with a the edge of a T-square) and fried the eggs on the hot tiles. They used cold tiles for plates.

This was the birth of a new art form! A lot of talk about that: how to design better, draw better, animate a figure better — so that it would jump, magically, off the page. Movies on paper — the final dream!

But even before the war the dream began to dissipate. The war finished the job. The best men went into the service. Hacks sprouted everywhere—and, with sales to armed forces booming, hack houses also sprouted, declared bankruptcy in order to not pay their bills, then re-sprouted under new names. The page rates went up to $15 a page for penciling, $10 for inking, $2 for lettering. Scripts got $5 to $7 a page — few artists wrote their own any more. Few cared.

The business stopped being thought of as a life’s work and became a stepping stone. Five years in it at best, then on to better things: a daily strip, or illustrating for the Saturday Evening Post, or getting a job with an advertising agency. If you weren’t in it for the buck, there wasn’t a single other reason. Talk was no longer about work. The men were too old, too bored for that. It was about wives, baseball, kids, broads — or about what a son of a bitch the guy you were working for was: office gas. The same as in any office anywhere, not a means of communication but a ritualistic discharge. The same release could be achieve through clowning: joke phone calls, joke run-around-errands for the office patsy, joke disappearances of the new man’s art work. Everyone passed it off as good fun in order not to be marked as a bad sport. By the end of the war the men who had been in charge of our childhood fantasies had become archetypes of the grown-ups who made us need to have fantasies in the first place.

Afterword

Respect for parents, the moral code, and for honorable behavior, shall be fostered.

Policemen, judges, government officials and respected institutions shall never be presented in such a way as to create disrespect for established authority.

In every instance, good shall triumph over evil and the criminal punished for his misdeeds.

From the Code of the Comics Magazine Association of America

1. In the years since Dr. Wertham and his supporters launched their attacks, comic books have toned down considerably, almost antiseptically. Publishers in fear of their lives wrote a code, set up a review board, and volunteered themselves into censorship rather than have it imposed from the outside. Dr. Wertham scorns self-regulation as misleading. Old-time fans scorn it as having brought on the death of comic books as they once knew and loved them: for, surprisingly, there are old comic book fans. A small army of them. Men in their thirties and early forties wearing school ties and tweeds, teaching in universities, writing ad copy, writing for chic magazines, writing novels — who continue to be addicts, who save old comic books, buy them, trade them, and will, many of them, pay up to fifty dollars for the first issues of Superman or Batman, who publish and mail to each other mimeographed “fanzines” — strange little publications deifying what is looked back on as “the golden age of comic books.” Ruined by Wertham. Ruined by growing up.

So Dr. Wertham is wrong in his contention, quoted earlier, that no one mature remembers the things.

His other charges against comic books — that they were participating factors in juvenile delinquency and, in some cases, juvenile suicide, that they inspired experiments, a la Superman, in free-fall flight which could only end badly, that they were, in general, a corrupting influence, glorifying crime and depravity — can only, in all fairness, be answered: “But of course. Why else read them?”

Comic books, first of all, are junk.*4 To accuse them of being what they are is to make no accusation at all: there is no such thing as uncorrupt junk or moral junk or educational junk — though attempts at the latter have, from time to time, been foisted on us. But education is not the purpose of junk (which is one reason why True Comics and Classic Comics and other half-hearted attempts to bring reality or literature into the field invariably looked embarrassing). Junk is there to entertain on the basest, most compromised of levels. It finds the lowest phantasmal common denominator and proceeds from there. Its choice of tone is dependent on its choice of audience, so that women’s magazines will make a pretense at veneer scorned by movie-fan magazines, but both are, unarguably, junk. If not to their publishers, certainly to a good many of their readers who, when challenged, will say defiantly: “I know it’s junk, but I like it.” Which is the whole point about junk. It is there to be nothing else but liked. Junk is a second-class citizen of the arts; a status of which we and it are constantly aware. There are certain inherent privileges in second-class citizenship. Irresponsibility is one. Not being taken seriously is another. Junk, like the drunk at the wedding, can get away with doing or saying anything because, by its very appearance, it is already in disgrace. It has no one’s respect to lose; no image to endanger. Its values are the least middle class of all the mass media. That’s why it is needed so.

The success of the best junk lies in its ability to come close, but not too close; to titillate without touching us. To arouse without giving satisfaction. Junk is a tease; and in the years when the most we need is teasing we cherish it — in later years when teasing no longer satisfied we graduate, hopefully, into better things or, haplessly, into pathetic and sometimes violent attempts to make the teasing come true.

It is this antisocial side of junk that Dr. Wertham scorns in his attack on comic books. What he dismisses — perhaps because the cause was made badly — is the more positive side of junk. (The entire debate on comic books was, in my opinion, poorly handled. The attack was strident and spotty; the defense, smug and spotty — proving, perhaps, that even when grown-ups correctly verbalize a point about children, they manage to miss it: so that a child expert can talk about how important fantasies of aggression are for children, thereby destroying forever the value of fantasies of aggression. Once a child is told: “Go on, darling. I’m watching. Fantasize,” he no longer has a reason.) Still, there is a positive side to comic book that more than makes up for their much publicized antisocial influence. That is: their underground antisocial influence.

2. Adults have their defenses against time: it is called “responsibility,” and once one assumes it he can form his life into a set of routines which will account for all those hours when he is fresh, and justifies escape during all those hours when he is stale or tired. It is not size or age or childishness that separates children from adults. It is “responsibility.” Adults come in all sizes, ages, and differing varieties of childishness, but as long as they have “responsibility” we recognize, often by the light gone out of their eyes, that they are what we call grown-up. When grown-ups cope with “responsibility” for enough number of years they are retired from it. They are given, in exchange, a “leisure problem.” They sit around with their “leisure problem” and try to figure out what to do with it. Sometimes they go crazy. Sometimes they get other jobs. Sometimes it gets too much for them and they die. They have been handed an undetermined future of nonresponsible time and they don’t know what to do about it.

And that is precisely the way it is with children. Time is the ever-present factor in their lives. It passes slowly or fast, always against their best interests: good time is over in a minute; bad time takes forever. Short on “responsibility,” they are confronted with a “leisure problem.” That infamous question: “What am I going to do with myself?”

Correctly rephrased should read: “What am I going to do to get away from myself?”

And then, dear God, there’s school! Nobody really knows why he’s going to school. Even if one likes it, it is still, in the best light, an authoritarian restriction of freedom where one has to obey and be subservient to people not even his parents. Where one has to learn, concurrently, book rules and social rules, few of which are taught in a way to broaden horizons. So books become enemies and society becomes a hostile force that one had best put off encountering until the last moment possible.

Children, hungry for reasons, are seldom given convincing ones. They are bombarded with hard work, labeled education — not seen therefore as child labor. They rise for school at the same time or earlier than their fathers, start work without office chatter, go till noon without coffee breaks, have waxed milk for lunch instead of dry martinis, then back at the desk till three o’clock. Facing greater threats and riskier decisions than their fathers have had to meet since their day in school.

And always at someone else’s convenience. Someone else dictates when to rise, what’s to be good for breakfast, what’s to be learned in school, what’s to be good for lunch, what’re to be play hours, what’re to be homework hours, what’s to be delicious for dinner and what’s to be, suddenly, bedtime. This goes on until summer — when there is, once again, a “leisure problem” “What,” the child asks, “am I going to do with myself?” Millions of things, as it turns out, but no sooner have they been discovered then it is time to go back to school.

It should come as no surprise, then, that within this shifting hodgepodge of external pressures, a child, simply to save his sanity, must go underground. Have a place to hide where he cannot be got at by grown-ups. A place that implies, if only obliquely, that they’re not so much; that they don’t know everything; that they can’t fly the way some people can, or let bullets bounce harmlessly off their chests, or beat up whoever picks on them, or — oh joy of joys! — even become invisible! A no-man’s land. A relief zone. And the basic sustenance for this relief was, in my day, comic books. With them we were able to roam free, disguised in costume, committing the greatest of feats — and the worst of sins. And, in every instance, getting away with them. For a little while, at least, it was our show. For a little while, at least, we were the bosses. Psychically renewed, we could then return above ground and put up with another couple of days of victimization. Comic books were our booze.

Just as in early days for other children it was pulps, and Nick Carter, and penny dreadfuls — all junk in their own right, but less disapproved of latterly because they were less violent. But, predictably, as the ante on violence rose in the culture, so too did it rise in the junk.

3. Comic books, which had few public (as opposed to professional) defenders in the days when Dr. Wertham was attacking them, are now looked back on by an increasing number of my generation as samples of our youthful innocence instead of our youthful corruption. A sign, perhaps, of the potency of that corruption. A corruption — a lie, really — that put us in charge, however temporarily, of the world in which we lived and gave us the means, however arbitrary, of defining right from wrong, good from bad, hero from villain. It is something for which old fans can understandably pine — almost as if having become overly conscious of the imposition of junk on our adult values: on our architecture, our highways, our advertising, our mass media, our politics — and even in the air we breathe, flying black chunks of it — we have staged a retreat to a better remembered brand of junk. A junk that knew its place was underground where it had no power and thus only titillated, rather than above ground where it truly has power — and thus, only depresses.

*1 The Funnies in 1929; Detective Dan in 1933; New Fun in 1935. The single unique stroke in the pre-Detective Comics days was the creation, by Sheldon Mayer, of the humor strip, Scribbly — an underrated, often brilliantly wild cartoon about a boy cartoonist with whom, needless to say, I identified like mad. I regret that it is not within the province of this book to give Mayer or Scribbly the space both of them deserve.

*2 Action Comics, June 1938

*3 Clip Carson, Action Comics.

*4 There are a few exceptions, but nonjunk comic books don’t, as a rule, last very long.