From The Comics Journal #79–80, January 1983–March 1983

George Pérez began drawing comics professionally nine years ago as an untrained rookie; his subsequent rise to superstardom has been nothing short of meteoric. His and Marv Wolfman’s Teen Titans is the bestselling comic in the direct sales market, and Pérez himself has become one of the most talked-about young artists in the field. Pérez was born in 1954 in the South Bronx. Not having the temperament of a street kid, Pérez retreated into the world of comic books and discovered a talent for drawing. A formal art education was beyond Pérez’s family’s financial means, so he is entirely self-taught. Pérez drew from the age of 5 but didn’t give serious consideration to drawing comics professionally until a friend convinced him to attend a comics convention and the rest, as they say, is history. Pérez joined Rich Buckler as an apprentice in 1973, but their approaches to drawing and their personalities didn’t mesh. So, Pérez went solo and was soon drawing Man-Wolf and Sons of the Tiger for Marvel. Pérez soon found himself working on the Avengers, the Inhumans and the Fantastic Four. Due to personal pressures and health problems, he cut his work back to such an extent that he had trouble meeting deadlines and maintaining a regular output. His career turned around three years ago when Marv Wolfman invited him to do some work at DC. After drawing a Justice League of America story, Wolfman asked him if he’d like to take a crack at a New Teen Titans book. Pérez initially thought the book would last only five issues but with its enormous commercial success and the more private professional fulfillment he’s found drawing the book, Pérez hopes to stay on the Titans through issue 120. — L.K. Speerloop

This interview was conducted in September 1982 by Steve Ringgenberg and Gary Groth. It was copy-edited by Pérez, edited by Groth and transcribed by Tom Mason.

*All scripts by Marv Wolfman and penciling by George Pérez unless otherwise noted.

STEVEN RINGGENBERG: George, where are you from?

GEORGE PÉREZ: I was born in the South Bronx, New York, June 9, 1954. So, I lived in that version of war-torn Berlin for 19 years, until I moved to the East Bronx — real gypsy in me — and I finally moved to Queens when I was about 23. And I’ve been here ever since.

RINGGENBERG: Where did you go to school?

PÉREZ: I went to Catholic high school, Cardinal Hayes Memorial in the Bronx. I’ve had no formal art-training. So, I never went to art school. I was accepted when I applied to the School of Art and Design but my mother, being a devout Catholic, wanted me to get a Catholic education. I went to a school hoping they had an art course; regrettably they had none. I went to a Catholic high school and just got a regular formal education, but no art-training at all.

RINGGENBERG: Are you entirely self-taught?

PÉREZ: Entirely.

RINGGENBERG: And you never picked up any night classes or anything after you started working for comics?

PÉREZ: We couldn’t afford it. At that time, I had just gotten married, to my first wife, and there was no way I could afford a night class. Also, as most newcomers are when they start out, pretty cocky and a little too self-assured. I figured, “What do these professionals really know?” I thought I knew it all. Learned the hard way that I was wrong, but at least it gave me a little puncture in my ego when I realized that I wasn’t that good. Had a lot of professionals who told me a lot of the troubles I had in my basic drawing. I was lucky I was a fast learner. I learned on my own, based on the fact that since the time I came in, Marvel had expanded and was cutting down on quite a few things. They were, I think, having economic problems. So was DC. I had to improve very quickly or else be ousted like many others had been. Basically, I had to improve on my own and started taking advice from Johnny Romita and other people to heart as opposed to putting it aside as just a bunch of criticism of my major talent.

GROTH: When was this?

PÉREZ: About 1974.

RINGGENBERG: How long have you been drawing comics?

PÉREZ: Just a little over eight years now.

RINGGENBERG: Were you doing comics for yourself before you were in the industry?

PÉREZ: Oh, sure. I’ve been drawing since I was 5 years old. My first medium was a pencil on a bathroom hamper. [Laughter.] I was just sitting there on the bowl and started penciling on the hamper, which my mother greatly appreciated. Then I started using paper bags, because I had a ghetto upbringing, and we couldn’t afford to buy stationery. So, to doodle, I was using old paper bags all the time. And just kept on drawing. It wasn’t until my freshman year of high school that a young kid who was a friend of mine, Tom Sciacca, who was a big comics fan —I mean, bigger than I was — introduced me to conventions, where I got the real bug, to make a living out of being a comics artist. He took me to a convention where I got my very first critical appraisal by a professional. I felt like I had just been bombed from above. I was really, really shell-shocked. I was hurt. I was disappointed. But at least it gave me the incentive to improve, because now I could no longer get by on the praise of fellow students who knew nothing about art. I learned the hard way that I had to start improving. And unfortunately, not having the training, it was a lot of hit-and-miss. When I started in the business, I was considered one of the worst in the business, and it was quite a reputation to get away from.

GROTH: Who appraised your work?

PÉREZ: When I was an assistant to Rich Buckler, he was the first one helping me out. He was the first professional training I ever had, working as his assistant, But there were editors there; Tony Isabella commented on the weaknesses of my artwork. A number of people, some contemporaries, I don’t remember who. But they were quite a number, and they were all right. My art was definitely below par.

GROTH: What kinds of criticisms were they?

PÉREZ: My lack of backgrounds, lack of knowledge of perspective, anatomy. The one thing they never complained about was my storytelling, my dynamics. That, they said, was my strongest suit. But as far as basic drawing ability, I had no knowledge of real anatomy, no knowledge of perspective, which is one of the first things I worked on. Everything was empty. I could not give a sense of place for the characters. If I had a futuristic setting, I may draw one panel dealing with the futuristic setting, and then totally ignore it for the rest of the story.

The thing that I’m proud of is that I can look back and say “OK, I was the worst, but not now.” I’d hate to think I was the worst, and still rated that way.

GROTH: Have you lived in this apartment long?

PÉREZ: In this particular building I’ve lived for about two years. My wife lived here first, before we got married, and I just moved in. Half of my stuff is now in storage. And I just bought these [bookshelf] units with the money I earned at a convention selling artwork [laughter]. The Titans artwork finally got on sale.

RINGGENBERG: How good is DC about giving it back to you?

PÉREZ: The thing they’ve done is change their personnel so many times that sometimes you don’t get the artwork at all. I just finally got all the artwork that was due me.

GROTH: You were talking about your work lacking a sense of place …

PÉREZ: Yeah, I did not know how to do a continuity of backgrounds. Continuity of figure, momentum from panel to panel wasn’t the trouble. I think Marv Wolfman pointed it out, and Marv was one of my harshest critics in the beginning. And I didn’t like Marv then, either [laughter]. He knows this. But he constantly got down on me for the weaknesses I had, because he was editor of the black-and-white line at the time. In one particular story, the “Sons of The Tiger” in Deadly Hands of Kung Fu, there was a bomb on a bridge, and I did not fully establish that there was a bomb there that would go off. So, there was no tension involved. And I established a bridge in the very first panel of the sequence. And then never established it again until it blew up. Which was a bad sense of place because you have to keep reminding the reader of where he is, where the characters are, and where everything is in relationship to them. So, I had to start learning that. And I finally developed that to a fine edge, where I can pretty much keep the character consistent with the background.

RINGGENBERG: What other kinds of art have you done in the past besides comics?

PÉREZ: Well basically, even though they weren’t comics per se, they were comics-oriented. Some work for National Lampoon. Science Digest, a science fact magazine with illustrations, wanted a comics format for a couple of pages. So even that was comics-oriented. And I haven’t done anything other than comics except for my own enjoyment. I’ve done portraits of friends, wedding portraits, things like that. But other than comics, I don’t have much time to do anything else.

GROTH: Can I ask how you started to work on improving your weaknesses? Like perspective and anatomy. Did you just buy books and study?

PÉREZ: No, actually I was self-taught there, too. I was a very good listener. I would hear people say things like vanishing point, and proportions, just basic generalities that they were talking about, and I would apply it until it looked good to my eye. I figured that if it looked right, it was probably right. And if it looked right to other people, it was probably right. So, I just did it as a hit-and-miss thing, without any formal investigation to find out the exact principle of it. I just kept on doing it. Marv constantly hounded me because I was doing perspective wrong on Sons of the Tiger, which was a great experimental book. I learned a lot working on that series. And finally, just got the knack, that I learned on my own. And it was a tough experience, Something that I would not recommend to anyone else. If you are going to be coming into comics, learn some of the basics of actual drawing. If it weren’t for my pushiness, I might not be working now. I wanted to make it in the business, so I pushed hard, for a person who was not really that well-equipped to negotiate. Saying “Hey, you should use my artwork.” Then they would ask why, and I wouldn’t have a good answer [laughter].

RINGGENBERG: What would you tell them?

PÉREZ: “Because you have no one else to do it.” That was my one advantage in the group books. No one else wanted to draw the group books, So I volunteered for it. Better getting someone with enthusiasm than a more talented person with none. The group books were something that I took because I enjoyed them, but they gave them to me because no one else wanted them.

GROTH: Are you fairly self-assured that you can do fairly complex perspective drawings?

PÉREZ: Oh, sure. I’ve done it so many times now. I enjoy a good challenge. If it looks challenging, it will take me longer, but I get a great feeling of accomplishment when I do it.

RINGGENBERG: Getting back to the group books, is that why you like drawing the group books — because of the initial, you know …

PÉREZ: Well, I’ve been a fan of group books since I’ve been reading comics. The first book that was actually a fan of was the Legion of Super Heroes, ironically, the only group book I haven’t drawn, practically. But I enjoyed group books from the beginning. Maybe it’s the interaction, or all the costumes, I don’t know. I like having characters interact. And I never get bored with one character, and if I do, I just draw another. I like the soap opera technique you can use when people react when they’re talking, open mouth, closed mouth, giving an ugly look, whatever. But it’s easy for me. Group books are actually easier for me than a single character, if not time-wise, then staying with it. Because I get bored with a single character very easily, and if I took a single character book, I’d leave it: Firestorm, while I enjoyed the graphics of the character initially, I did want to get off it. I was only supposed to be there for two issues, it ended up being four, then five. But I did want to leave the book because a single character doesn’t thrill me as much as a bunch of characters, particularly if there are more women involved in the groups. I love drawing women.

GROTH: We know. Isn’t the drawing more complex in a group book because you have more characters to organize?

PÉREZ: Oh sure. It requires a special choreography, but I enjoy it. It’s easy for me. I do not design my pages ahead of time. I just design them as I draw them, and I know how to arrange the groups. My only hassle is, as with almost any group artist, that I’m drawing in black and white, and these characters are in color, you have to watch yourself. Sometimes, I bunch all the red-colored characters on one side without knowing it, instead of intermingling them. But that happens all the time because I’m not working in color. That’s the only problem. Everything else is just so easy. And the only hassle I sometimes have as well is that in working with a writer, they tend to write their books in the same way they would write a single-character book, which means they’ve got a lot more action than you can possibly fit in because of all the characters that are involved in it. It takes a lot of pacing. Most of the writers, thank goodness, give me the option of what I will leave in and what I will take out and how I will pace the story. They give me a lot of leeway there. And thank God they do, because otherwise it would be hard to characters. So, it’s easier to do your work now that you are more established and can have more input.

RINGGENBERG: So, it’s easier to do your work now that you are more established and can have input.

PÉREZ: Input is one thing that I’ve always had the advantage of. From working with Dave Kraft and Bill Mantle right at the very beginning of my career on Man-Wolf and Sons of the Tiger, they both, since they were starting themselves, gave me a lot of input in to the books. I worked briefly with Roy [Thomas], Gerry [Conway], Steve Englehart, Marv, and they gave me the same amount of leeway also for the simple fact that they saw what I could do. And after one or two issues of trying to develop a working relationship, they entrusted me with a lot more. Marv entrusts me with everything.

RINGGENBERG: How closely do you guys work together?

PÉREZ: Very closely. Marv only lives about half a mile from here anyway. But Marv and I have such a simpatico relationship on the Titans that there are times when I will call him, or vice-versa, to suggest an idea, and he will have thought of the same idea or a similar idea, the night before. He gives me very, very loose plots, depending on how much of a physical or cerebral story it is; the plots vary. But usually, he gives me a fairly loose plot and I will draw it without putting a single liner note on the book, which is very unusual. Most artists have to put liner notes in to tell the writer what’s going on. I don’t put any liner notes in for Marv, and a good 85–90 percent of the time, he’ll know exactly what I meant in the story. And what he does not understand, he’ll make better. So, I have no complaints of the way Marv handles it. And it’s the closest working relationship I’ve had with anybody. The fact that he and I are close friends, we live close together, and we co-created characters, does give us the closest working relationship I have ever experienced.

RINGGENBERG: Do you guys hang out together?

PÉREZ: From time to time, sure. He invites us over to the house. My wife and his wife invite each other out for lunch and stuff like that. So, it’s a very nice relationship.

RINGGENBERG: When you were working for Marvel you were working on characters that other people had created, and now you and Marv are working on characters that essentially you all created. How is your approach different working on someone else’s characters instead of your own?

PÉREZ: When working on established characters, it’s almost like you have the shell there and you are animating the statues, trying to put life into something that is physically there. From the Titans, we are working from the inside-out. We know the characters as individuals, we have a lot of ourselves in there. So, we work from what the gut feeling is, to their reaction, and then the character develops physical self, based on those inner feelings. The characters work from the inside-out, as opposed to just being animated statues, which is what I had on the Avengers. The Titans are more alive because I’m the poppa, the co-poppa [laughter] and that makes all the difference in the world. We understand the characters inside and out, as opposed to having to research them.

RINGGENBERG: How does your attitude about a particular character affect the way you draw him?

PÉREZ: Well, take Cyborg. Since I was born and raised in the ghetto and Marv was not, it gives me a certain insight into the character that would never have been there otherwise. The fact that he’s become big, tough, a little hard-bitten, mean-tempered, but still mush on the inside. The character would have been totally different in his development if it weren’t for my experiences, my upbringing. Marv usually gives me a lot of leeway on his characterization. In fact, when we did the Cyborg story for the first issue of Tales of the New Teen Titans, it was one of the first times I almost reconstructed a whole plot; just to make the character seem real, because even Marv wasn’t satisfied with the way it looked when he did the plot. So. I reconstructed it, built up his relationship with his mother, which was almost nonexistent in the plot, and just totally turned it around. There’s an example of a character who would have been totally different if it were done by someone else. And as far as the insights to the characters and the way we built it up, it’s usually Marv and me discussing back and forth, and disagreeing back and forth, about what a character would and wouldn’t do, which you couldn’t do as much with a pre-established character because we know them enough. We know what they won’t do because we established the pattern of the character. So that’s basically how the characters have been motivated by us.

GROTH: Are you and Marv given almost complete freedom to do with the New Titans what you want?

PÉREZ: Sometimes too much so. They feel that the Titans sell well, they can trust us, and that when we make mistakes, they sometimes let it slide, which they shouldn’t. I’ve made some art mistakes, or some things that Romeo [Tanghal] misinterpreted, which were let go because they figured, “Well, we can trust this book.” I don’t think any book is that good, that anyone should be given full freedom because we are all going to make mistakes. Marv’s made mistakes, letterers have made mistakes, I’ve made mistakes, Romeo’s made mistakes, and if they are not caught and corrected, the book is going to keep suffering for it. We are given a fairly autonomous hand but not so much that the thing’s going to be anarchic.

GROTH: What kinds of mistakes? Are these minor things?

PÉREZ: Well, minor things, and some things that bother me only because you spend enough time designing it. In the first appearance of Blackfire in issue #23 of the Titans she’s supposed to wear black leather. But at that time, I was doing layouts on the book, there were no blacks put on her costume. I didn’t put the blacks, and neither did Romeo. And since she had already been drawn two or three times, and I had already drawn her on the cover. I drew a fully rendered version of her in the issue before so they could have some guidelines. When that wasn’t caught and she appeared throughout the entire issue without the black highlights on her costume to give the look of leather, that annoyed me, because that established the character. And now you have a character named Blackfire without any black on her costume.

Typos. In the Annual, a proper name was spelled differently three different times.

GROTH: [Laughs.]

RINGGENBERG: In the same issue?

PÉREZ: The same issue. As it turned out there were two proofreaders on Titans, because Len [Wein] was at a convention and was not proofreading at the time. So, it’s things like that that should not be allowed to happen because mistakes like that cheapen the look of the book. We do have clout; we do have quite a bit of control over the book, and I’m given quite a bit of control over the covers. But it is still not so much control that Our Word Is Law, which it shouldn’t.

RINGGENBERG: How close are you to the Titans as characters?

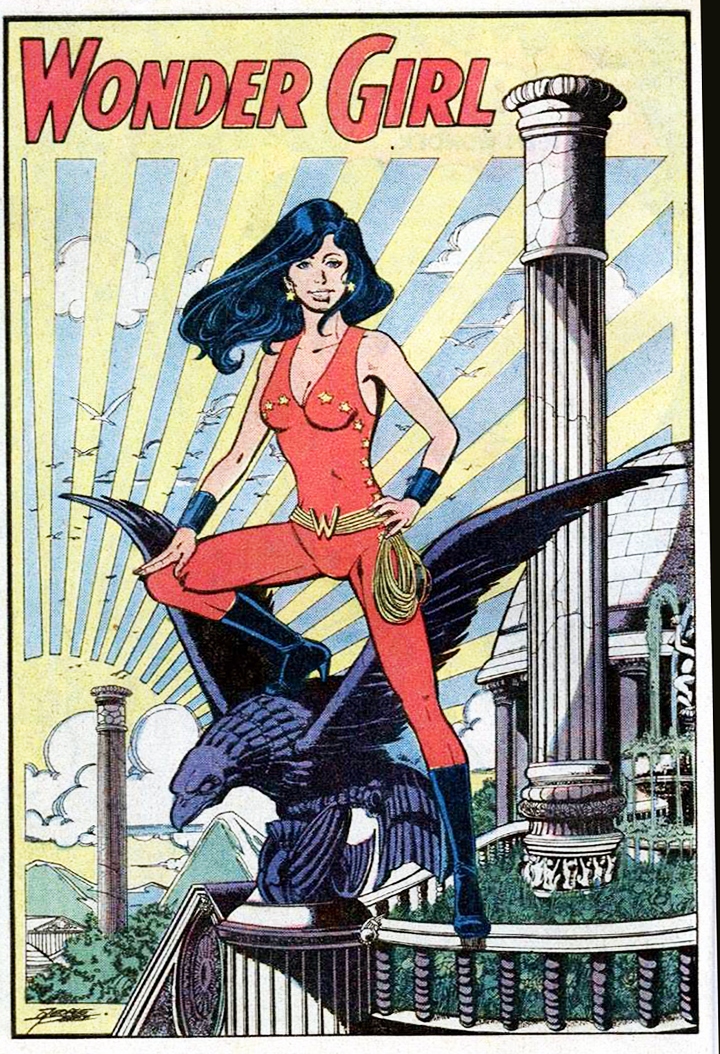

PÉREZ: Very, very close. I know those characters; I love those characters. Let’s face it; those characters resuscitated my career. And I have the greatest pleasure in doing them because of the fact that it’s more of an emotional experience, as well as a cerebral experience. I enjoy drawing them. The characters are becoming more and more human-looking as I draw them. Marv has commented on the faces, on the subtlety. Wonder Girl looks a lot more human now.

RINGGENBERG: Robin.

PÉREZ: Robin looks more human … There’s one scene in which Robin is dead tired. He’s been wasted a bit by the fact that he has so much to do, and he’s got five jobs. How many people can handle five jobs without getting a little wasted? So, he’s developing more of a human look. They all are. Even the Barbie-doll look of Starfire is becoming more moderated and there is a softness to her. She always does look human despite the alien highlights on her body. And Raven doesn’t look anything like she did when I first co-created her. It was just totally amazing. She looks totally different without the hood. When I first took it off in issue 4 she has a totally different face than she does with the new face that was established in issue 8. And it’s been worked on since then. And even Kid Flash has had a new face developed for him. He’s gotten different looks so he doesn’t look like Robin. And we’ve re-introduced Speedy into some of the storylines, he makes an appearance in issue 27, and he has a totally different face, because otherwise he would end up looking like Robin. I had to develop a different face for him.

RINGGENBERG: Were you influenced by Adams’s depiction of Speedy?

PÉREZ: I tried not to, because except for hair color, his depiction of Speedy didn’t look too much different from Robin. Because he never had to draw them side by side really, except for one Titans story that was inked by Cardy anyway. So, I had to draw him with a totally different look. I changed the shape of his nose, he’s got a slightly wider face than Robin does, doesn’t have the cheekbones that Kid Flash has, and his hairline is slightly higher. Little, subtle things like that. His nose was a big thing, and I gave him a very tight lower lip, not a full lower lip the way Robin and Kid Flash have. And that developed a fuller face for him that looks the same when he’s Roy Harper and when he’s Speedy. That face is always the same because I developed a code for the faces.

GROTH: Did you change their faces over the issues as their personalities, codified in your own mind?

PÉREZ: Yes. They started to become distinctive human beings and I couldn’t do the type of thing I was doing at Marvel where they had interchangeable heads. I could have put Steve Rogers’s head on Thor and there wouldn’t have been much of a difference because I was just doing standard faces. And now they all have individual faces. My test was to draw them all without hair, so their hairlines could not identify them. If they could be recognized without their hair, then I had developed individual faces. And also, the supporting characters are starting to be fleshed out a little more. It’s become a book of people. I enjoy drawing the non-action sequences more than the action sequences of the book now. Something I would never be able to say about the other books, because I enjoy seeing them in action. I enjoy seeing them loafing, talking, getting to know each other. And I enjoy those scenes more than just the slam-bang action.

RINGGENBERG: How much do you identify with specific characters?

PÉREZ: Cyborg I identify with because of my upbringing. Most of the others are not so much identity things as opposed to people I have known or characterizations of people. Sure, when Marv writes it, he has certain bits of characterization based on either experience or imagination that he puts in as well, so it becomes a collection of things. But Cyborg is the closest to me as a person. And a lot of the characters who appear are based on the characters I’ve known. Frances Kane, who made an appearance in issue 17, is based on a young girl named Fran Costanzo who I know personally. We had to change her name and everything because of the nature of the story.

The redesigning of Raven, because Raven is one of the few characters who has actually gotten slighter. Her bust has gotten a lot smaller, she’s gotten thinner, she’s developed more of a dancer’s body, and that was based on a young lady I know who dances in the same dance school as my wife. And she has a nice light body and all. And even facially looks a little like Raven with the hood on, but she doesn’t have the eyebrows and the crazy hairstyle. But he’s a very attractive young lady and I’ve used her as a physical basis though, nothing more.

But most of the characterization with the exception of Cyborg is mostly Marv’s doing. We talk it out, but Marv has the biggest hand in how the characters behave. And whatever motivation he had to have the characters behave that way, it works well.

RINGGENBERG: Do you have a favorite character that you like to draw more than any of the others?

PÉREZ: Well, obviously Starfire. And she’s also the one I get the most requests to draw. She’s become the individual representation of the Titans. I enjoy Cyborg because the fact that he’s just a gritty character. But as far as the most fun to draw, the one that comes very easy, is Starfire. She is without a doubt the most popular of the Titans.

RINGGENBERG: She just like flows out of your pencil, man.

PÉREZ: Easily. And Romeo has even mentioned that when he gets a page and Starfire’s on it, she’s the first one who’s inked. He loves her also. Romeo loves inking Starfire.

RINGGENBERG: It was a little crazy in that one story where you met Starfire’s parents and there were all these masses of hair.

PÉREZ: Right. All these lion manes, which is the way we established the feline race. I always forget, I don’t even know if the parents’ names were ever established. Were they?

RINGGENBERG: I don’t remember.

PÉREZ: I don’t remember either [laughter]. But I love those characters, I loved doing that particular sequence. Again, just the little personal touches. My one regret was that the story was just so big, I was running out of room. I would have loved to have given that a lot more space.

RINGGENBERG: Like the reunion with the parents?

PÉREZ: Yeah, the reunion. I just had no real room to do what I would have loved to have done. Really build-it up, maybe give it an extra two pages. But the pin-ups had to go in because I had promised to do those three pin-ups. And. the story was just so big that I couldn’t afford to keep doing small shots. I had more large panels in that than was normal.

RINGGENBERG: Getting away from the Titans, is there a character that you’ve always wanted to do, but never had the chance?

PÉREZ: … Metamorpho.

RINGGENBERG: Really?

PÉREZ: I enjoyed Metamorpho. I really did when I was young. The Legion as a group I would love to handle, for one story.

RINGGENBERG: Any possibility of doing a Legion story?

PÉEEZ: Well, now that Keith Giffen is so enthusiastically with the book, it isn’t like I can say “Want me to fill in?”

“Oh, thank you, yes.”

Keith loves doing the Legion of Super-Heroes, so there’s hardly any opportunity there. As far as any DC characters, since I’m doing the History of the DC Universe, every single character they’ve created, I’ll have drawn, so that’s no trouble. As far as Marvel is concerned, while I did him a lot while I was doing the Avengers, the one single character I enjoyed drawing and would not have minded doing a single story with was Iron Man. I enjoy drawing Iron Man.

RINGGENBERG: Because of the metallic highlights?

PÉREZ: The metallic look, yeah. Bob Layton once mentioned that his version of Iron Man was influenced by mine, because finally he got the metallic look to him. I’m not sure, but I think I based mine on Starlin’s. So, everyone else has some kind of influence. And I’m sure Jim had some kind of influence himself when he did his version.

RINGGENBERG: Which artists have influenced you most?

PÉREZ: The earliest influence was Curt Swan, then there was Kirby, of course. Ditko, just for the sake of the ballet approach to the body. Neal Adams, Barry Smith, Jim Starlin, Gil Kane, John Buscema. There were quite a number, but those are the major ones. I’m sure there are some I’ve slighted. John Byrne. Byrne and Starlin were the last major influences as far as noticeably looking at their style for influence. There are other more subtle influences. People like George Tuska, whose hands I studied. Little things like that. But those are probably the main ones. Almost anyone who produces decent quality work has been an influence at one time or another.

GROTH: Can you talk about what artists influenced you in what way? In other words, with regard to Barry Smith, it looks like his layouts have had an influence …

PÉREZ: Yeah. And the detail work. The fact that he did so much in one panel, and I like the idea of filling up as much as I can. Starlin the same way, although I liked his dynamics more than Smith’s. His bodies moved better. I just loved the way Gil Kane drew figures flying, jumping. I loved his Spider-Man, and I loved his Green Lantern. I enjoyed his Atom when he did that. Just the fact that his characters seemed to move. I love the folds in clothing that he did. Now, there’s a strange reference. I love the way he draws folds in clothing. And the way he does water. He does great water, that Gil. Jack [Kirby], obviously, was the dynamics. The sense of bigness that he did on all the books. Obviously, Jack was not an influence on my drawing women [laughter], with all due respect to Jack. The. If you are going to be coming into comics, learn some of the basics of actual drawing. dynamics, the power, that no one else has ever really matched.

RINGGENBERG: Also, his battles.

PÉREZ: Yes. Jack had everyone look like they were made out of rock. When I did the sequences on Paradise Island it gave me a more realistic look. John Buscema again. His characters tended to look a little more beefy than Neal’s did. Neal was a big influence in learning how to draw women, as was John Buscema. Curt Swan was the quiet touch I needed so I didn’t go overboard. I loved Kirby but didn’t want to be Kirby. I didn’t want to get that strong as an action artist. I would lose all sense of softness. At DC I’ve developed a subtlety of character which is what I’ve always wanted to have. I’ve envied John Byrne’s ability to produce it. The quiet moments. And that’s where John Byrne was a great influence. The sense of design and his ability to do the quiet things were big influences. And facial expressions: Neal, Byrne, and Curt. Those were probably the major ones. And there were a lot of minor things. Kirby’s rocks, for instance. I was basically a comics fan who picked them up from the stands. Williamson, and Krenkel’s work, I’m still not as familiar with. Alphonse Mucha as far as fine art, So I tried to do a little Art Nouveau. My wife was big into Mucha and introduced me to it. Maxfield Parrish was another one I started looking at, because of his great knowledge, of faces.

RINGGENBERG: Have you looked at any strip artists like Raymond or Hal Foster?

PÉREZ: I loved Kerry Drake. I was mad as hell when they took it out of our local paper. But I enjoyed Kerry Drake. Probably one of the few realistic strips I actually followed. Williamson when I started looking at some of the old stuff. And Alex Raymond. Ah, that was great stuff. And Leonard Starr. You could expand upon it, but the nucleus is still Raymond. I’m not so stylized that I can only do one thing. The History of the DC Universe is going to give me a shot at everything. The only thing I wish I could do is the Warner’s cartoons. That type of funny animal thing, which I’m not proficient at. Never having practiced it and never having time for practical application. I would like to do that just to entertain kids at conventions or non-comics functions. Lord knows the number of times when I say I’m a comic book artist a kid asks me to draw Bugs Bunny.

RINGGENBERG: So that’s something you would like to do besides superheroes?

PÉREZ: At least to know how to do it if asked. Like if I were asked to do Captain Carrot right now, with them saying they need it tomorrow, I’d have to go to the store and get all the issues of Captain Carrot just to learn how to draw those funny animals. Not to draw them exactly but just to get the knack of drawing funny animals. I’ve never done it before. But I’m always in for a challenge. Who knows. If they ever read this thing, I may be in for a weird phone call. This Peter Ledger airbrush work. Ah, neat stuff. I was stuck up with this sort of snobbery saying that superhero art is the only realistic art that was of value, and then you start seeing the value of people you may not have … Look at Grandenetti, he and his horror stuff at Warren. The early stuff, not counting Prez, which because of my name I despise. [Laughter.] You see people like Alex Toth. He puts in just enough.

The one thing I do enjoy about Romeo is that he’s constantly trying to improve. There was a time when I thought that the inker should be taken off or I’ll leave the book. He was strictly a brush artist, and he learned how to use a pen more for his backgrounds. And I’ve since asked him to use a pen more, and his backgrounds are superb. But very few people can match Romeo for his faithfulness to the faces I draw, because he knows them almost as well as I do. I am very happy with his inking now, but I wasn’t for the first few issues. I’m not the only one who’s been helping him. Dick Giordano’s been helping him, and you can’t ask for a much better teacher than that. I love to ink my own work because I think I have a much better sense of the faces than Terry [Austin] would. But realistically, if I want to make money, I’ve always loved his work, and I’ve told that to him. And if ever he wants to work on something, a graphic novel or whatever, I would love to work with, Terry Austin. There. was a time when I thought I would prefer Terry to Romeo on Titans; but now that Romeo’s got it down ... I love Terry’s work, but Romeo has a sensitivity to the characters. Pablo was a little closer but he was a little rushed. Ernie was rushed. But I was probably the most pleased with Ernie Colon’s, which was fine. And Gene Bay was a personal choice for the Changeling issue. And what he lacked in the faces he made up for the same reason that Brett Breeding did, the extra rendering that he did. The only thing that disappointed me was that they didn’t have Romeo’s experience inking my faces issue after issue. Very few people can top Romeo for being faithful to my faces. I’m probably the only one who’ll do it better than he does.

RINGGENBERG: How satisfactory over all have they turned out?

PÉREZ: I was very happy. I was very pleased because the books had some Blacks write in saying it was nice to see a good fair treatment of Blacks in the ghetto, an individual look. The way Marv handled the story, the way they were designed. The first issue was inner city, the second was nightmares; then a comedy, then a science fiction-fantasy. And they all had such an individual nature that it did separate them. The one thing I was afraid of when we did Tales of the Teen Titans was that it wouldn’t have any difference from the regular Teen Titans book. Otherwise, why do a miniseries if it’s not going to be something special? And with Marv and me sitting down and deciding how these stories were going to be different from each other, it worked out. As far as Marv’s concerned, the proudest thing he did was with Changeling. And what we thought was going to be the weaker story, in some people’s letters, it was their favorite of the four-part miniseries. Strictly because he wrote it totally against what I had drawn, which was deliberate. In which I would draw something, and he would contradict it all with the dialogue. And it was magnificent. I enjoyed it. Some people criticized it for being too wordy, but that’s Changeling. He talks a lot.

GROTH: Since we are talking about characters you know so well, what did you think of the X-Men/Teen Titans crossover?

PÉREZ: I think Chris [Claremont] did a marvelous job with a group that was [little] more than a year old. There were a few flaws, granted, out of lack of experience. Starfire was the one character I think he didn’t quite hit on the mark. All of her real characterization took place in stories after he had written his story. So, he had very little to work with. But as far as the execution, I thought it was very well done. Walt and Terry have given me a very hard act to follow when I do the next Titans/X-Men. But my experience is that I have drawn the X-Men, only for one Annual, but it is experience. And I have been the only artist, practically, to handle the New Titans. So, I do have a certain advantage there. And the same thing, the Justice League/ Avengers story. The only other people who have drawn both the JLA and the Avengers are Neal, very briefly, and Rich Buckler and Don Heck. And I look forward to it because I have a good working knowledge with all the group books So far. Except for the Defenders, but then again, I didn’t really care about the Defenders. [Laughter.]

GROTH: Who did? [Laughter.]

PÉREZ: Yeah.

RINGGENBERG: With the X-Men/Titans crossover, did you have much contact with Chris, Walt and Terry?

PÉREZ: I don’t know about Marv, but they didn’t get in contact with me because the only reference that Walt needed obviously were The Titans are more alive because I’m the co-poppa and that makes all the difference in the world. The comics that were published. I’m glad. Because when I draw the X-Men/Titans, I wouldn’t want, say, John Byrne or Someone giving me art tips. I think it would have been an insult to Walt if I told him how to draw. And I think it would be an insult to me if he told me how to draw. The reason they have Walt there is to get Walt’s interpretation, not Walt’s interpretation of my interpretation. So, they didn’t get in contact with me and I’m glad they didn’t. It was nice, pure Walt Simonson. And I don’t think Walt does enough work that comes into the limelight, even though the sales on Star Wars, and some of the others are decent. Somehow his super-hero work is not as appreciated as it could be. And the Titans/X-Men was a nice spotlight that was highly overdue.

GROTH: You said the Titans resuscitated your career. Were you stagnating at the time?

PÉREZ: Oh, At one point, I remember Al Milgrom asking me, “George, I heard you were getting out of comics.”

I was going through a divorce. And I had a lot of personal hassles at that time, and I was doing less and less work. Now I produce between three and four pages a day during a good week.

RINGGENBERG: Is that a comfortable rate for you?

PÉREZ: It’s still a heavy load because I put more work into every individual page than maybe other people will. Out of my own choice, it’s not a bravado or anything. It’s the only way I feel comfortable. I do work a lot, anywhere between 12 and 15 hours a day.

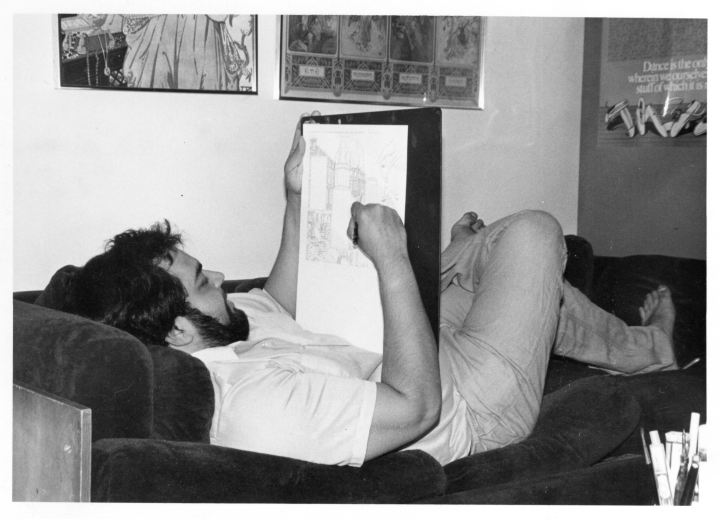

RINGGENBERG: What are your work habits like?

PÉREZ: You see that couch? That’s my drawing board. That’s my seat. I lie on that couch, have a lap board which is just an old drawing slate, which I lay on here, put my piece of paper down and draw. And the TV’s usually on too. [Laughter.] The most unprofessional attitude you ever saw.

RINGGENBERG: I notice that a lot of artists seem to draw with the TV on. Mike Kaluta does. If I was drawing it would drive me crazy.

PÉREZ: It’s more of a controlled noise. I couldn’t take a lot of, say, street noise all the time. But it’s controlled noise, a background hum. And sometimes it’s also a visual rest. Like after drawing for a while, then looking at the TV, you’ve rested your eyes from the concentration of drawing. You let your mind go blank and receive rather than send out. So sometimes it’s just a nice visual rest. Looking at TV, looking at something, something that’s moving. Since the picture’s always changing, it’s not like looking at something that stays the same, is always stagnant. At least TV provides something different to look at other than the drawing board, picture, and anything else that surrounds it.

RINGGENBERG: Like, 12 to 15 hours sounds pretty heavy, man.

PÉREZ: It is a heavy schedule. I try not to work weekends, though.

GROTH: You were talking about your situation and Milgrom?

PÉREZ: Oh, yeah. So, I was doing, for a while, three-and-a-half books a month. I was doing Avengers, “Sons of the Tiger,” The Fantastic Four, and The Inhumans. And little, by little they were being sliced down. Until eventually, I was doing one book a month and barely making that. I was having a hard time doing that. I was going through enough emotional instability that I couldn’t handle any other pressure. So, I ended up not doing a regular monthly book. The Avengers was the last one. I made a mild comeback with Logan’s Run. But then again I went through Some kind of nerve disorder. So, I couldn’t draw for two weeks because I couldn’t hold a pencil. And after Logan’s Run, I was freelancing on assignments. I was still working with Marvel, but there were very few things that they ever saw from me regularly. I couldn’t stay on a book except for maybe two or three issues at a time. And then I was off again. So, I was becoming unreliable. The Titans, now I’m working on issue 29, I’ve only missed issue 5 in the entire Titans run. And I’ve done four miniseries chapters, and the Annual, and for a while I was even working on Justice League while still on Titans. So, I’ve managed to get back the reliability. But that’s what I meant by resuscitating my career. Because then I was starting to do Marvel Two-in-One, came back on the Avengers for its 200th issue which was a disappointment to me because it seemed like a story that didn’t go anywhere. It didn’t make any sense because no one knew exactly what they wanted from the story. And I was just treading water. I was a comic book artist who was there, but I could have been anyone else. One thing I always wanted in the business, I guess anyone wants in the business, is to be exceptional. And I had gone from being an exceptional person because of the amount of work I was doing to run-of-the-mill, to a person who might be a special, or even nondescript treat by just appearing in a couple of things. I did a book called Sgt. Pepper’s Lonely Hearts Club Band, which was the nadir of my career. [Laughter.] I mean, it was so horrible.

RINGGENBERG: Was that a movie tie-in?

PÉREZ: It was a movie tie-in and it was so horrible …

RINGGENBERG: Well, it was a horrible movie.

PÉREZ: Oh, it was an even worse comic. [Laughter.]

GROTH: Wasn’t that only published in Japan?

PÉREZ: Only in Japan, and it was done to pay them back for Pearl Harbor, I think, really. [General laughter.]

GROTH: We finally got them.

PÉREZ: We finally got them. [Laughter.] Hiroshima wasn’t enough, So we sent them Sgt. Pepper. It was horrible, definitely the low point, in my career.

GROTH: I never saw it; I assume you can get us a copy of the book?

PÉREZ: I don’t have a copy of the book. They didn’t give me a copy. I didn’t want one [laughter]. When they finally returned the artwork, I gave it away. It was horrible. Horrendous. My artwork was about as substandard as when I started, and that’s how far back it had gone. I had actually gone downhill.

GROTH: Just because of the stress you were under?

PÉREZ: The stress. And this book was cursed. We weren’t getting any cooperation from the [Robert] Stigwood Organization. So, it was a book that seemed doomed to die from the very beginning. I had no reference on it, They kept cutting out scenes and putting in scenes, telling us who was going to be in it and then finding out they were not in it. Erasing heads. It was a lousy book, and I really had to do something to get out of that. And even though I was doing The Avengers at that time, I really didn’t feel as satisfied as I could be. In particular I guess because of the disappointment of Avengers #200.Until Marv asked if I’d be interested in doing something over at DC. That’s how the Titans came along. And it boosted me up. I’m finally up on the upper echelon. People have mentioned … that I think I’m one of the top 4 people who get called to conventions now. Which is a great feeling, and Something I hope to keep working on. I intend to stay on the Titans until issue #120, because that will break the late Dick Dillin’s record on JLA — he has the record of most consecutive issues of anyone on one book. And it will also make a nice even 100year run on the book. And Marv says he’ll stay on it as long as I do, so that means we are safe. And Romeo’s not going to leave it as long as I’m on it. So, we have a fairly steady team for quite a while.

RINGGENBERG: What do you think is responsible for the Titans’ great appeal, beyond technical virtuosity?

PÉREZ: In particular, the X-Men’s popularity. If the X-Men hadn’t been popular, Lord knows if the Titans would have. We got a lot of the X-Men audience initially, just to see what everybody’s talking about with “DC’s X-Men.”

GROTH: Does that irritate you?

PÉREZ: No. Initially, when they first told me, we knew we were going to get that. But I’d rather DC’s book be compared to a good83’’Because if it was just a cheap copy, it would have died at this point as far as direct sales, anyway. And at least in direct sales, Teen Titans outsells X-Men. And the only book that outsells Titans in direct sales, is Daredevil.

MIKE CATRON: Let me ask a couple of quick questions here and then I have to leave. Did growing up in the ghetto have any influence in your gravitating toward comic books?

PÉREZ: I needed to escape. Reading comics was obviously not a popular past time there because most of the kid were very heavily into sports, or gangs. I did not like gangs, I’m not particularly a violent person. And I just had to do Something that would take the place of going down into the streets. I was involved in only one fight when I was young and I was quite young, and I was beaten up. I made sure that I would not be down there again. When I went to high school it was different because I had to travel, So in turn I did a little more exercising, got into weightlifting. Something at least that would make it harder for someone to come and try to start a fight. I’ve. only been involved in several minor skirmishes since then, which I’ve usually won. But art was the one way where I would not have to get into that. I enjoyed drawing. It was a fantasy world. It was an escape at first and after a while, just sheer enjoyment. And when I got to high school it was also a way to meet new people. When they saw that you could draw, they gravitated toward you because you were different, you had Something special. And it was in high school that I realized that this was Something that people did admire and not just Something to be used for an escape. My brother even drew when he was young, but my brother was a street kid and he gave up drawing before he turned into his teens and potentially, from what I remember of his artwork, he probably would have been better than I was. But he gave up and couldn’t draw worth a damn now. He just never had the heart for it.

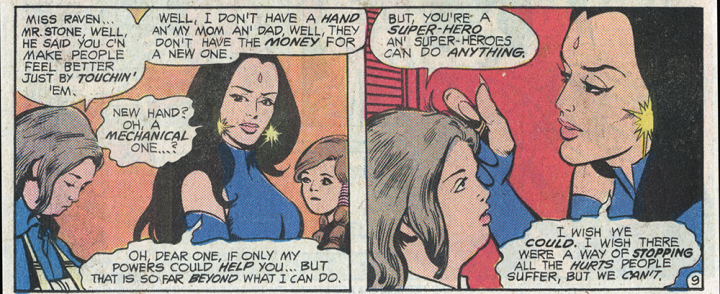

GROTH: Did you ever characterize yourself as a street kid? Originally, Marv Wolfman only had Cyborg walking through the park. Pérez added this touching sequence with the little boy.

PÉREZ: No. I wasn’t there enough. They knew me there, but I wasn’t popular there. They knew I didn’t like them. They knew I had contempt. The kid who beat me up is now in jail. But not because he beat me up [laughter]. But because he went into a life of crime. As a lot of people did. It was a mutual contempt. I did not like being their Marvel book, than a bad Marvel book. I would hate for them to say that this is DC’s version of the She-Hulk [general laughter]. Then, I’d be concerned. But if they say it’s DC’s version of The X-Men, OK, it’s a compliment. The one thing that we did establish as the issues went on was that it did have an identity of its own. The one thing chat worked for us was the one thing we wanted to get rid of initially, the name “Teen” Titans. But since we had to use the name Teen for some copyright reason, the fact that they were teenagers did give them an identity of their own, because the X-Men are not teenagers anymore. So, we started developing storylines using that. And then they were no longer DC’s X-Men, with the exception of the fact that they were DC’s best-selling book, a resuscitated book, the same way the X-Men were for Marvel. Other than those superficial similarities, they each had individual identities. And Marv and I were never displeased with the phrase that we were another X-Men book. But it did give us the incentive to make it more than just that. And they didn’t like me there, and I was just as happy to finally move on.

RINGGENBERG: The opposite of Jack Kirby growing up on the streets.

PÉREZ: Except that when Jack grew up on the streets, it was different than when you grew up in the South Bronx. Jack’s in his 60s. So, he would have grown up on the streets of New York about 1920-something.

GROTH: He’s 67.

PÉREZ: Sixty-seven? OK. And I was growing up there in the 1960s. So, there was a lot of unrest then.

RINGGENBERG: The vibes were a lot meaner.

PÉREZ: Minority troubles were there. It was a Puerto Rican/Black neighborhood. And anyone who was not with them was against them. It was a very tense time. And I was not with them. And that’s why when I got into high school I started pumping up, making sure I that I was bigger. I always had the idea that they would love to attack me. My mother knows a lot of people there now, and a lot of them know I’m a comic book artist, and now I’ve got the respect, not because I was bigger than they were, but because I got out of there. I think deep down inside, they all wanted to succeed; I was one of the few who did.

GROTH: When did you get out?

PÉREZ: I moved out, because of my first marriage, at 19. But it wasn’t until I started getting notoriety as an artist that anybody even noticed that I was out of there. “We remember him.” And it was a good feeling. It was also a good feeling when my parents finally moved out of there. I had been begging them to move out of there for some time and they moved out a little over a year ago. And they finally moved to a different area. It’s not a lot better, but it’s different. So, I was just glad to get out of that center of the ghetto.

RINGGENBERG: Cyborg, how much of your upbringing do you bring to your work?

PÉREZ: The grittiness, the violence, and knowing how to drawbacks, and ethnic types. A lot of artists have trouble drawing ethnics. It’s second nature for me. Because I am an ethnic and I’ve lived among them for so long. So, they became something that I was quite used to drawing. I received a compliment when I was down in Texas recently. This Black man came up to me and said, “l like the way you draw Black people.” It’s something that not too many people notice because you figure the best thing is that it’s so realistic that it doesn’t call attention to itself. I try to draw Cyborg as an amalgam of a lot of Black people I’ve known. Sometimes I don’t think of it consciously, but when I do I come to realize what that ghetto upbringing did do for my artwork.

GROTH: What other than your art? How did it affect your social attitudes?

PÉREZ: I found myself gravitating toward people who were not of my own ethnic persuasion. Since I went to a private Catholic high school, where you had to pay tuition, and I was from a lower income area, not too many people from my neighborhood went to the same high school. So, I got to meet a greater variety of people. And I enjoyed being with them more because I really did not seem to fit the stereotype, or mold of an average Puerto Rican in the South Bronx. I have since accepted the fact of what I am. There was a time when I hated it. Because of the bad stereotype, the constant feeling of being trapped, and the feeling of danger that always surrounded me.

CATRON: You hated the fact that you were Puerto Rican?

PÉREZ: Oh, yeah. I hated it. I hated the stigma of what people always expected from a Puerto Rican. I’ve had a few bouts with prejudice in my time. I remember dating one girl whose father hated Puerto Ricans. And when I was with my own, I never felt it as much because. they aren’t going to be calling you a dumb Puerto Rican because they are themselves. [laughter]. But because of my art, my artistic temperament, I didn’t want to go into a violent stage. I wanted to find the beauty in life. I was alienated in my own ethnic background and sometimes felt alienated when. going into other ethnic backgrounds. So, for a while, I Anglicized myself. I tried to hide what I was. If they said, “Are you Puerto Rican,” I said “No, I’m an American.” I’ve since become proud of what I am, mostly because I’ve met a lot of Puerto Ricans who have succeeded on their own. I was blaming a race because of people I had bad experiences with. But I’ve gotten to accept it a lot more, to enjoy it: I am quite proud that I am Puerto Rican, and a successful artist. And I’m in a career where my race meant absolutely nothing. They couldn’t care less what my last name was, just what I could produce with my talent. And it helped get rid of some of that hate that I carried for so long. And now I’m “proud as peaches.” [laughter]. Ernie Colón and I are two of the most successful Puerto Ricans in comics now.

RINGGENBERG: Do you think a book like the Titans can be a positive force for educating kids?

PÉREZ: Sure. For one thing, it educates me. Well, Marv is Jewish, he was born in Brooklyn, and how much in common we really have, in common about our knowledge of human beings, not much is really different. It’s just that when you are ghettoized you feel it’s only your type of people whose wrongs are centralized in this area. But all the wrongs and rights are everywhere. It educates me and educates other people. The first issue with Cyborg opened up a lot of people’s eyes. Some Blacks actually wrote in saying it was nice to see a fair treatment of Blacks in the ghetto.

GROTH: I think with Cyborg, you’ve been praised for not making him a stereotypical angry young Black.

PÉREZ: Which is what everyone was afraid of at the very beginning. But Marv had the idea and he knew exactly what he was leading up to, going into issue #7 where his father dies. That was the turning point in the character. But Marv had it planned. It was all going to be wait and see. He was not going to put all his cards on the table immediately, or else he would have nothing to do later. He was willing to stand up to the angry letters because many of the things he kept me in the dark about. But when the fruition of his plans came along, as in issue #7 or “Day In The Lives” in issue #8 it was worth it. And the people who stuck by were even more surprised to see “My God, they went from one angle to another and made a smooth transition instead of changing him overnight.”

CATRON: What do you think it is in your work that appeals so strongly to the fan market?

PÉREZ: Well, I hope not only the execution, which I’m very proud of. The amount of work that goes into it, the dynamics. The personal love that goes into each page of what I’m doing. And I love what I’m doing. A lot of letters come in saying that you can tell that George and Marv love what they do. I sincerely love what I do. I wouldn’t trade it for anything. I’ve had offers for commercial art and everything else. The fan market thing is fine, there is an ego stroke there that everyone needs. But I genuinely love doing this. And even with all the problems I’ve had, the ups and downs of my career, this is the career I hope to stay in for the rest of my life. I was born to be a comic book artist. I love doing it, I think I’m good at it. And when I love what I do, I produce the best work, and I think that’s why the Titans are so popular. There’s just something extra. The subtlety of the people’s emotions show through because there’s a comfort that I have in 9ealing with them.

GROTH: A certain commitment that is communicated?

PÉREZ: Yes. The characters are not just going to go through the paces, they are going to live in those pages. One thing I have to be careful of is on weekends when I don’t work, to get away from the Titans. Because they are still just drawings on paper [laughter]. And I always have to separate reality from fantasy.

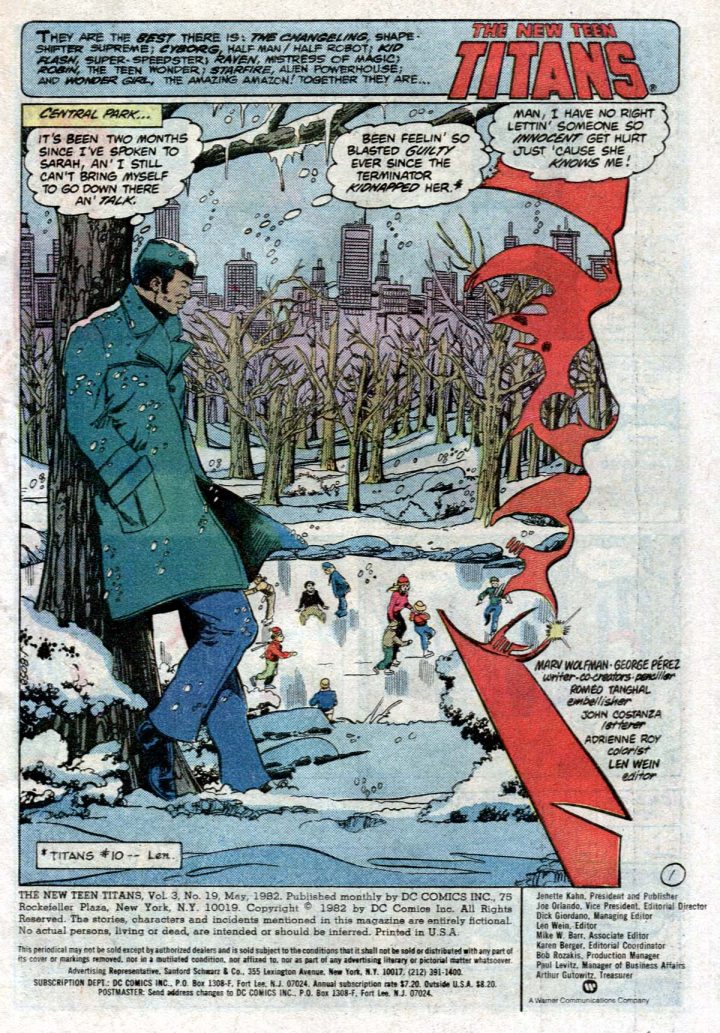

PART TWO OF THE GEORGE PÉREZ INTERVIEW

This interview was conducted in September 1982 by Steve Ringgenberg and Gary Groth. Part I of this interview appeared last issue. It was copyedited by Pérez, edited by Groth, and transcribed by Tom Mason.

RINGGENBERG: Do you find that being such a popular artist among the fans has had an inhibiting effect on your work? Are there things you can’t do because the fans might not like them?

PÉREZ: No. I draw to please the fans, but the first thing I do is to try to draw the best book possible. So technically I am trying to please myself because the only criterion for the best book is what I think is going to be the best book. So, I try to do innovative things that I feel I have to do in order to improve. Both as far as my ability and for the way the book is going to look. And I think the fans appreciate the innovation, or at least the trying of something, even if it falls flat on its face. I’ve gotten criticism about certain things, and one of the things I’ve got to watch out for, are too many panels on a page. And in order to get rid of that, I will get rid of borders, reorganize a page, the design. Just do Something different. And when I start talking to fans, and they offer advice, I greatly appreciate the advice — I sincerely care — but you can never judge by one fan. I draw with the fans in mind, but I don’t draw for the fans. I can’t, because no two fans are going to agree. So, it is not a burden because mostly I don’t think about it. I hope they enjoy I’m glad they enjoy. But most of all, it has to be the best I can do. And I can’t be self-indulgent either.

RINGGENBERG: So, you don’t feel any great critical pressure?

PÉREZ: No. The only pressure that Marv and I felt was that DC’s sole skyrocketing book was the Titans and that the pressure of them exploiting the Titans was heavy. Doing the miniseries was okay because we got to go into the characterizations more and that would have taken a lot longer in the regular book. And the Annual was an actual progression; since there was a line of annuals, it didn’t seem we were picked out. The exploitation of the book is the thing we worry about. When the Titans appear in other books, Marv makes it a point to tell them not to put on the cover a statement that they are appearing in the issue because you are exploiting them. Like DC is worth nothing, right, except for this one book. I’m looking forward to Frank Miller’s new assignment, and the other books that DC is coming out with. I would like Something to outsell or sell nearly as well as The Titans for DC. If nothing else, to get rid of the pressure of being the one real success they have. That’s the only thing I fear. I think that hurt The X-Men a bit, having way too many X-Men things on the market. It cheapens it. It’s like saying Marvel cannot do anything unless the X-Men are there, because that’s the only way to guarantee sales. Which is not true, but it looks that way. And I don’t want them to say, “My God, we’ve got a good book, let’s put the Titans in there.” It’s unfair; you are only artificially raising sales and you cheapen the reputation of the company.

RINGGENBERG: Did the success of the Titans surprise you?

PÉREZ: Oh, sure, I thought the book would be cancelled after six issues.

GARY GROTH: Really?

PÉREZ: Realistically, I was doing a new book for DC, and DC’s track record being what it was at the time, I figured the book was going to die. Even if we produced our best work, I didn’t think enough people were going to take a look at it. Obviously we underrated the fan. But it was a book I did strictly as a favor to Marv and a shot to do one issue of the JLA. So, I did it, figuring five issues not counting the giveaway. So, a total of six issues, and I’ll be off, the book will have been cancelled, I’ll have done my best, and everyone will be happy, blah, blah, blah. Issue #5 was actually the one issue I missed. And the sales were going up slowly but were still no match for any of the Marvel books. But it finally started catching on. By issue #13, #15 we had broken 100,000 in direct sales. We were attracting a lot of attention, the book as succeeding. Now I’m nearing the 30th issue of this book, and there seems to be no end in sight. The sales are constantly up there, we are the No. 2 seller for both companies, and the enthusiasm is still there. Marv and I already have the basic plot for issue #50 down, because we have something special planned for #50. We want to marry Wonder Girl off in that issue.

RINGGENBERG: And get her out of the book?

PÉREZ: No, no, keep her in. Just a nice healthy relationship where he does not get involved in her super-hero stuff; he’s not Steve Trevor or Lois Lane. He’s a teacher, and she doesn’t go into the classroom and tell him how to teach, and he doesn’t go into Titans Tower and tell her how to be a superhero. So, they will be happily married. He won’t be kidnaped or anything. We want to do a double-sized book for #150, because I’m going to demand a double-sized book and get rid of the super-heroics in the first 10 pages or so and use the remaining 30 pages for the wedding — civilian wedding. She’s getting married as Donna Troy, not as Wonder Girl.

RINGGENBERG: And have the Titans there in civilian clothes?

PÉREZ: Yeah, because obviously they are not his friends. It will be the human side of it. And in the 30 pages we aren’t going to have any gate-crashing supervillians. Just a straight wedding where the whole issue is characterization. The Titans proved, particularly with issue #8, “Days in the Lives,” and from the letters we got, people really want to see the nice human touches to the characters.

GROTH: You said it was the #2 seller; does The X-Men outsell it?

PÉREZ: No, Daredevil. X-Men is #3.

RINGGENBERG: Any complaints about the industry you work in?

PÉREZ: Well, Sometimes the checks are late [laughter]. But that’s the way it is in most publishing. Sometimes it takes a month, sometimes two weeks.

What I really regret is that there are a lot of people who have been working a long time and are not in their prime as far as potential, and as far as their output is concerned. And they missed out on all these wonderful innovations, the royalties and all that. They are not fan favorites and they won’t get the kind of assignments from which they can benefit the most from the new programs, the financial rewards. That’s the only thing that bothers me when you think about people like Curt Swan. I’m entitled to royalties, and a nice hefty amount, and Curt is not. But Curt has been working for them for 40 years, and that doesn’t seem fair. I wish there was something that could be done.

RINGGENBERG: Wouldn’t you say that the fact that you are getting royalties now is more of an exception than the way they are treating Swan?

PÉREZ: Well, Curt’s being treated very well. I do have a creator’s credit and Curt doesn’t because he didn’t create Superman. And as far as Siegel and Schuster are concerned, if there were no fuss about their rights, I would not be getting royalties now. And I agree that they did not get what they should have gotten. But when I came into the business, I did not expect royalties. I came in with my eyes open. I knew this business. Obviously for them, it was a new experience. When the royalty thing came in, I wanted it. I fought for it too. But I was not going to leave the business if I didn’t get it. I got into the business not expecting royalties. And when they did get it I was glad. I wish it was more fair to those who have worked before us. But it’s like any publisher, you only pay for what is successful now. And if your books aren’t selling as well as the others, you aren’t going to get as much. I’ve heard there are going to be changes for the people who have worked a long time, like for foreign sales. Because Curt’s done a lot for foreign sales. He may benefit from that, I don’t know. But they are trying, despite a lot of criticism to the contrary. Even though the big, corporate heads are giving it a game try. I have no complaints. I’ve benefitted a lot. And I know Paul Levitz, who has been maligned by other people, has struggled like crazy to get this legal thing drawn up. And he’s one of the people responsible for getting us so much of what we wanted. I was talking to Frank Miller, and he was offered some other work and he turned it down, not because he didn’t have the time, but because he was making quite enough from comics and didn’t need it. Five years ago, when did you hear anyone say, “I earn enough from comics, I don’t need. any outside work?” It works very well for me, but I can’t speak for others who may have had bad experiences.

RINGGENBERG: Have you been approached by any of the independent publishers?

PÉREZ: All of them. [General laughter.] I’ve turned down most. I’ve been approached by Pacific, Fantaco—I’m doing a four-page story for Fantaco simply because I said I would before I got all of this other work. Schanes and Schanes wanted to do an “Art of George Pérez” book, but I don’t have time to do one. And I’m negotiating with Marv as well to do a portfolio for Schanes and Schanes. Marv would do a short story that would accompany my illustrations. So, it would be a little different. And others have called up. As for the Art of George Pérez, four different publishers called up about doing one of those things. But if there was one, it wouldn’t be until 1985. Because I have enough stuff, not including the Titans, to keep me busy for the next couple of years.

MIKE CATRON: Are you afraid of burnout?

PÉREZ: Of course, I’m afraid of burnout. When I finish all these big projects, and there’s even talk of a Titans Graphic Novel for mid ’84 or something like that, I’ve told my wife around 1984, 1985, I’m through with all this stuff. I’m just going to spend a year doing Titans. Nothing else. I won’t be accepting another bit. of work other than Titans. Mike Golden said, “Bullshit,” which is what my wife thought the book would be cancelled after six issue said, though she wasn’t as graphic. And they are probably right. Despite my fear of burnout, I’m a workaholic; I can’t go cold turkey.

RINGGENBERG: What do you do to relax?

PÉREZ: I go out with my wife, watch movies, television, do a little shopping. A few months ago, I went a whole week without doing a single drawing. And one thing I try to do on weekends, unless I’m working to meet a deadline, I don’t pick up a pencil at all. I just divorce myself from my professional life. And I don’t use drawing as a recreational thing, I find something else. Just basically relax, turn my brain to neutral.

CATRON: Do you dance?

PÉREZ: No. I like to but those are all my wife's dance trophies. Quite a talented little lady.

CATRON: What would happen next year if you stopped being a fan favorite, you just became a reliable journeyman penciler? How would your ego handle it?

PÉREZ: My ego would probably be hurt. My greatest feeling of elation was seeing my name mentioned in the Comic Book Price Guide. A book actually being sold on the merit of having Pérez art in it. That was a great feeling. And I wanted that feeling. If the light suddenly shifts, and moves on to someone else, I would have had my day. It just means I’ll have to keep on improving. When I get to the point where I feel I’m doing my best work, then I’ll be in danger. The next issue should always be my best work. If I realize I don’t have to improve, then I’m going to regress.

RINGGENBERG: What are your favorite films?

PÉREZ: Well, certainly fantasy films. I like well-acted dramas. One of my favorite films is Inherit The Wind. I like interaction with people. I like musicals, my wife though more than myself, but lately I’ve been getting into them. The MGM musicals with Fred Astaire. Adventure films. Almost anything. I don’t like things that are a little too artsy. Federico Fellini. I love Steven Spielberg. The man is a comic book artist on celluloid. The man is magnificent. There’s no really central thing I enjoy more than others. I love to study film, maybe do some amateur directing. Just get together with a group of fans and do an amateur film. Eventually I’ll probably work on one, if ever I have the time and the money. I’m saving for a house now.

RINGGENBERG: How does film affect your work?

PÉREZ: Constantly. I keep in mind that the characters are constantly moving and I’m just freezing one frame every time I draw them. I have to keep in mind that they are moving continuously and that will lead to another angle. So, I try to keep a cinematic flow. I do not have the artsy construction of a page the way Frank Miller does, because he takes a cinematic approach and adapts an entire page and makes it work for him. I try to use the restrictions of a rectangular panel and apply cinematic techniques to that without changing the construction of an actual comic page.

RINGGENBERG: What about how it affects content?

PÉREZ: Um.

RINGGENBERG: Say you just saw Citizen Kane; how would you interpret that into a comic book story?

PÉREZ: The characters would get more shadowy. I would probably do more things with the Art Deco backgrounds. I’m constantly looking at backgrounds. And anyone who has seen my artwork would know why. I will study the way people are posed next to each other. And then switching camera angles and remembering where everyone is in that scene. When I do a dialogue scene or any scene that is going to last for a couple of panels, I always keep constant the position of the characters in the establishing shot or show a person actually walking from one place to another, just to keep the whole thing flowing; to give it a continuity.

RINGGENBERG: Here’s a technical question. What medium did you execute the Titans Annual cover in?

PÉREZ: I used Dr. Martin’s coloring dyes for the bright intense colors, then I mixed them with water in order to get some of the lighter muted colors, The line figures in the background were done with India Ink . . I used different color inks for different lines and then just colored around them. And for the regular characters, I used the regular India ink and for the gray sky I used both gray wash and pencil, streaking it with a sno-pak. And the bright turquoise blue that I used for the mountains were magic marker.

RINGGENBERG: Would you like to work in different media on the Titans?

PÉREZ: Sure. I’ve always wanted to do a detective story with Robin trying to find out Wonder Girl’s origin, and I want to do a Mickey Spillane cover, a pulp type cover in which Robin is in these deep shadows. More of a painting. Marv said he didn’t think there would be any trouble in them okaying that. Titans is now a book that they are willing to experiment. with. And using wash on #26, “Runaways,” was one of the things I wanted to do. But I’m not that good of a painter so I couldn’t do a full painted cover. But I definitely want to try mixed-media stuff. They didn’t think that cover on the Annual was going to work, they didn’t think it would reproduce well. And I was surprised that it came out.

RINGGENBERG: What’s been the response to the cover?

PÉREZ: Fantastic. I already sold it [laughter]. Some soldier in California bought it before I even got it back. It was very, very well received. It was about the first time I ever worked in that media before. So, it was all hit and miss, hope for the better. There are a lot of flaws in there that I really want to improve. But at least it was a chance to try it. The next annual is going to be a lot better than that. Get it right. Or close to it.

RINGGENBERG: I’d like to see you do a cover in airbrush. I think it would work well with your style.

PÉREZ: I’m going to get an airbrush when I get a house because I don’t want to subject my neighbors to the sound of an air compressor in this building. These are mostly fixed income people.

RINGGENBERG: Does Marv ever make suggestions about your art? Does he give you a bunch of notes or just call you up?

PÉREZ: He gives me just a few ideas as far as visuals. But he usually lets me have Carte Blanche on it. He did suggest for improvement on a recent issue that there weren’t as many close ups, as many intense close-ups as I used to do. He made that suggestion, and looking through the book, he was right. Marv used to be an art teacher, So I take his advice to heart, because obviously he do. es know what he’s talking about. He makes up in knowledge what he lacks in ability. I agree with a lot of it, though I may disagree with Some of it but I always appreciate it.

Marv is one of the best technicians that comics has ever had. Not only is he a good writer but he knows how to make things work and why things work because he is able to explain it a lot better than I can.

RINGGENBERG: He’s a great teacher.

PÉREZ: He is. And when it comes to telling you what to do, and how to do it correctly, or how it feels ii: should be adaptable to your style, Marv is one of the best. Len Wein is another one. They both have a good working artistic sense. And that’s important. to any writer.

RINGGENBERG: What’s been your favorite story so far?

PÉREZ: I think the “Runaways” issue has taken the place of “A Day in the Lives,” as far as my favorite Titans story. Because there was so much commitment to that story to make it the best it could be. We tried to. make it the most researched and intense story we could on the subject. And its similarity to “Day in the Lives” in that they are both personal stories. The characters are very much individuals there. I think the most current one is my favorite so far.

RINGGENBERG: Marv was on TV recently, wasn’t he?

PÉREZ: On The Today Show.

RINGGENBERG: Talking about the Titans success?

PÉREZ: “Runaways”: he was there for a meeting on the runaways situation, in Washington DC, or Some kind of press conference that was covered by The Today Show. He neglected to tell me about it: [laughter] and I didn’t find out about it until it had already aired. But they’ve got it on tape so I’ll be able to see it. But that story was very important to Marv. It was a story that would not have worked as well in any other comic except the Titans because they are teenagers. I’m very proud of it, and I’m sure Marv is too.

RINGGENBERG: Would you like to see the book do more social commentary? Like the O’Neil Adams issues of GL/GA?

PÉREZ: No, that’s not what the book was created to be. It’s good to do once in a while when you find a story that works within the framework of the series. If it does become a message book, it will alienate too many people because people do want to be entertained. So, the book is to be entertaining. There are too many other books around for the responsibility to be tossed onto .one title. We did our:’ bit, and I’d like to see other books carry the ball. Primarily, the book is supposed to be entertainment.

GROTH: Are you very political?

PÉREZ: No. I’m not. There are certain basic rights I feel everyone should have. But I’m not really very involved at all.

RINGGENBERG: Why do you use so many tiny panels?

PÉREZ: Have you ever tried to fit that many characters into a Marv Wolfman script [laughter]? Marv is not as used to doing group books as I am. And it is hard to fit that many intense characters into a storyline which has a lot in it. I leave out a lot and I still have w put all those panels in. Not to any fault of Mary as a writer, it’s just that it’s very hard in 23 pages to get a story in which there are seven very intensely characterized people. They are each supposed to be living individuals in the story. So, it’s a lot of squeezing. And I’ve tried to put larger panels in to offset that, but there are still some pages with eight panels to a page. Which is actually an improvement for me because I used to put 12, 14.

RINGGENBERG: What’s the most number of panels you remember putting on a page?

PÉREZ: Probably 22. [Laughter.] I think I remember Rich Buckler saying he could fit 32 panels on a page and still get in a large panel [laughter]. And I have yet to see Rich do it [laughter].

RINGGENBERG: What do you think has been your best story artistically?

PÉREZ:: There are a couple. “Runaways,” because I penciled that a lot more heavily than others and probably I think X-Men Annual #3, where I finally got to work with Terry [Austin]. And the amount of work that went into that, my detail and Terry’s extra detail, was the most satisfying combination I had up until Romeo working with me on the “Runaways” story. Those are probably the closest to fulfillment of what I want. Hopefully the next one will be better.

RINGGENBERG: Do you ever give extensive color notes?