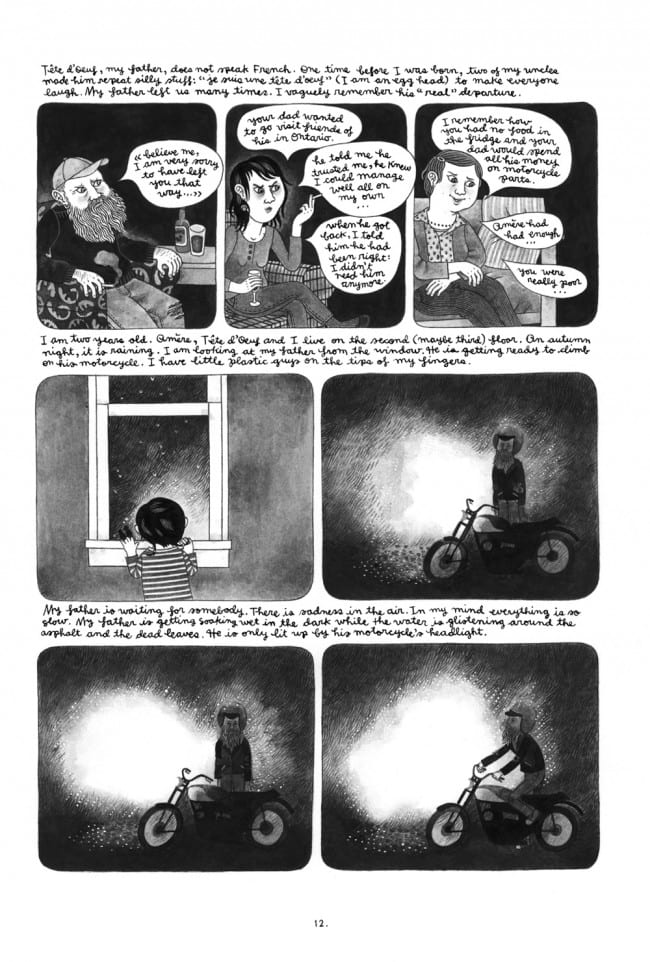

Geneviève Castrée is a Quebec-born cartoonist and musician whose gorgeous, carefully observed autobiographical graphic novel, Susceptible, was published in February by Drawn and Quarterly. In her comics as well as in her one-person music project, Ô Paon, Castrée’s sensibility is poignant but never maudlin, even when, as she does in Susceptible, she recounts complex and often painful moments from her childhood years, growing up in Quebec with a young single mother. Castrée, who now lives and works in the small Pacific Northwest town of Anacortes, WA, spoke with me recently over the phone about making art as a self-conscious person, the difficulties of writing truthfully about people close to you, and the relative virtues of walking away from conflict instead of resolving it. -Naomi Fry

Geneviève Castrée is a Quebec-born cartoonist and musician whose gorgeous, carefully observed autobiographical graphic novel, Susceptible, was published in February by Drawn and Quarterly. In her comics as well as in her one-person music project, Ô Paon, Castrée’s sensibility is poignant but never maudlin, even when, as she does in Susceptible, she recounts complex and often painful moments from her childhood years, growing up in Quebec with a young single mother. Castrée, who now lives and works in the small Pacific Northwest town of Anacortes, WA, spoke with me recently over the phone about making art as a self-conscious person, the difficulties of writing truthfully about people close to you, and the relative virtues of walking away from conflict instead of resolving it. -Naomi Fry

“I Mostly Have Psychological Reasons for Wanting to Live Here”

Naomi Fry: How long have you been living in Anacortes?

Geneviève Castrée: Well, officially, as in legally, for about eight years. Before that there was a lot of coming and going and immigration confusion, because my husband and I wanted to move to Canada, but we couldn’t figure out where we wanted to live in Canada, and in 2005 I finally said, although it wasn’t really my life’s goal to move to the USA, that we should move here. My husband was raised in Anacortes, and I didn’t really have a sense of roots anywhere. It’s a small town and there aren’t many young people, which actually gets difficult socially sometimes. It’s great for families, but if you don’t know if you want to raise kids [Laughs,] or you don’t know what you want to do with your life, this is a terrible place to be. You have to have something going on to live here.

It’s pretty unique for an active artist to live in such a small place. How does it work for you?

I mostly have psychological reasons for wanting to live here. It’s funny, I can talk a lot, and I can totally take up space in social situations, but overall I’m quite introverted as a person, and I really appreciate the space. I am rich in space here. It’s actually really nice that way. There’s this sort of magical power to Anacortes. The amount of money we pay per month to own a house here is probably half what somebody would pay to rent a place in New York. I have a room that I can close the door to and make a studio out of, and if I want to make music I have several options, there’s a room in my house that I can use for that, or we also rent this old Catholic church in town that some friends and my husband and I can access whenever I want and make music and practice. That’s the beauty of living in a small town. Since there’s always an exodus to the cities, the artists who choose to live in small towns have all these resources.

I often wonder what it would be like to live in a smaller place.

It’s kind of a total cliché to say this, but this is one of the advantages of this weird digital era we live in. If you’re a cartoonist or a musician or a writer there’s a long list of jobs that you can do from home, and it’s expanding. That’s the exciting part. you don’t have to be in a large city center anymore. I do miss the sense of community. Like, living in this town I really crave women peers who are closer to my age, who make art that I can relate to. Often, if I meet an artist who lives in this town it’s a seventy-year-old lady who does paintings of dolphins [Laughs.] And they’re like, “I know exactly how you feel!” And I’m like, I don’t think you do [Laughs.]

“In fact, I hope you don't” [Laughter.]

“Weird, Bold Things”

Before Susceptible, your first book with D+Q, you were publishing with L’Oie de Cravan in Montreal, right?

Before Susceptible, your first book with D+Q, you were publishing with L’Oie de Cravan in Montreal, right?

Yeah, I was a teenage cartoonist. The first book that I did with L’Oie de Cravan came out in 2000, when I was 18. I was a lot faster when I was younger. I guess maybe my style or the drawing itself was less developed. And then I did a couple more books with them. The third book, Pamplemoussi, was also a record. That was the first time that I made music. I thought, ok, I want to make a book and I want it to have music, and I don’t want anyone else to write the music, I’m going to do it. So I kind of had to teach myself how to make notes with the guitar, just to figure out a way to write songs and find a way to make some sounds come out of a guitar as I was singing them. And it was after that, in 2007, that I made another book that included a record, in collaboration with K records.

So you weren’t at all a musician before you made music for your own comics?

So you weren’t at all a musician before you made music for your own comics?

No, I wasn't.

What was it about the connection between the visuals and the music that you felt had to happen?

I don’t know. It’s not like I’d never ever considered making music before. When I was a really really little kid I went to this arts oriented school, for the first grade, and we had violin lessons in the morning. We didn’t go very far, we played “Frère Jacques” and that’s about as far as it went [Laughs.] But I do wonder often now that I look back, maybe it just awoke something in me, the way a child who is exposed to a foreign language as a baby has an easier time learning languages as an adult. And I was really obsessed with music as a teenager and I did have a lot of moments where my friends and I would “jam” in a basement, but I didn’t know how to play guitar and I mostly yelled lyrics that I made up on the spot. But I did know for a while that I wanted to make music and this was sort of my chance. People can be really bold when they’re young. I was 20 or 21 when I first got the idea to make music. And I think you do these weird bold things you might not have the self-confidence to do later on. The more I think about making music the more embarrassing I think it is [Laughs.]

Isn’t the whole idea of creative endeavor sort of embarrassing? For me it’s writing, but whether you’re a cartoonist, or a musician, or a writer, isn’t there a level of self-consciousness about the whole idea of self-expression?

For me, with music, even if I just had a show to play tonight, just the act of getting up on stage in front of a bunch of people and singing from the heart (Laughs,) if you think about it too hard it’s never gonna happen: like, oh my god, look at me, I’m singing in this pretty voice, these lyrics that I applied myself to write. If you think about it your lyrics start to sound, like, who the fuck do I think I am? (Laughs.].

Before talking to you I went online to look at Ô Paon videos, and there’s this one clip where you’re wearing this green hood, and you’re singing in front of an audience?

Yes, this was here, in Anacortes, as part of this festival we organize, my friends and my husband and I, which we used to call What the Heck. That hood video, that’s a great example of how embarrassing it can be, the only way it can happen is if you don’t think about it too hard. I had this costume thing that I had made for this photo shoot I was doing with a friend of mine for this other music project that I do called Urine [Laughs.] I just had this costume and on the day of the show I grabbed it on my way out and as one of the organizers of the festival, I was working the door and telling these volunteers what to do, and there’s all this stress, cause I have twenty people staying at my house, and the only way I could switch to performer mode was just to put this dumb green coat over myself (Laughs.] In trying to explain it, in hindsight, it’s like, yeah, I’m wearing this green cloak, because green is the color of nature, trying to give it any other meaning sounds so stupid [Laughs.]

When you switch into performer mode, or even writer mode, or artist mode, you need some sort of theatrical permission to say: ok. I’m doing this. And recognizing this and finding that you need these switches to do these borderline ridiculous acts…

I think that “borderline ridiculous” is a really good way to put it, actually. Because that’s what it feels like sometimes. I know plenty of males feel like this, and I hate making these generalizations about gender, I’m most definitely a feminist and I hate being like, this is what men do, this is what women do. But socially, I think that even if your parents are the coolest, raddest, want to help you break gender boundaries… basically even if your parents are doing this tremendous job, you go out into the world and you go to school, and in school you’ll learn these dumb stereotypes you’re supposed to fit into. And little girls are told to be pleasant, and to please, and boys are told to be boisterous and sturdy and have confidence, and to lose that fragility as a woman, like, oh, people are going to take pictures of me when I’m doing these really ugly faces on stage and I have to be ok with it, it’s really empowering but it’s also… the only way to deal is to completely remove myself… I’m so self-conscious so much of the time that the only way I can be onstage is to stop thinking.

It sounds very stage-centric, what you’re talking about, but can it apply to your comics, especially because they’re so personal? Is it easier to write about yourself as a child and a teenager, rather than, say, as a 26-year-old?

With Susceptible, it wasn’t that embarrassing for me, because the things that happen in it are from such a long time ago, and when you’re a kid you’re just inherently more vulnerable, you’re in this position of, whatever stupid thing you do, it’s not exactly fully your fault yet. I mean, I haven’t really processed what it was like for me as a 26 year old. Also, there’s a part of me that wants to keep it private, since it wasn’t that long ago, I feel as if I’m in exactly the same place I was when I was 26 years old [Laughs.]

But, you asked if it was stage-centric, and actually, I do think it applies for a lot of forms of art. I didn’t go to art school. I just went to high school, got my diploma, and that was that. But I have so many women friends who I really thoroughly admire who have had a fancy-pants arts education and who don’t work in anything related to what they studied, and when they do make art, it sounds horrible to say, but it’s kind of weak, some of the time? Like, a friend who went to this incredible art school made an art show of felted things. I’m not saying that you can’t make something that’s felted and is rad, but if you make a show of felted woodland creatures, why did you need to go to art school? But I think it’s self-consciousness – “I’ve seen other people do it and it works so…”

So do you feel lucky in a way that you hadn’t had an extended arts education?

Yes, I often feel lucky. Mostly because I don’t have that debt to pay back! [Laughs.] But, I feel that I was really unruly, I got out of school and I just wanted to do my thing. Who knows how long I can keep this up? But for the time being… I mean, I stand by everything I made, at least from the point where I started having somebody else publish my work. I sure hope that I do better things now, but I’m not embarrassed by those earlier comic books. And I feel like maybe I had more time to do trial and error before making my D+Q debut, instead of having my D+Q debut be when I was twenty.

“It Took Me 11 Years”

How did the connection with D+Q come about?

Well this is really ironic to say after I’ve told you this story, but the first time I was actually approached by D+Q was when I was 20. I met Chris Oliveros when I was 18, we went to this comics festival in France and there was a big group of people from Quebec. And then when I was 20, I remember I got my first email from Chris in 2001, talking about how he’d like to publish a book by me. And so it took me 11 years to come up with something where I could say, would you like to publish this? [Laughs.]

So, seriously, you’ve been in touch for eleven years?

Yeah. Doesn’t that sound really really really dumb? [Laughter.]

So how did that work? Did you keep in touch occasionally, or did you just lose touch for nine years and then two years ago you were like, hi, I have a book? [Laughs.] This is really fascinating.

I don’t know! [Laughs.] Well, first I felt a huge sense of loyalty to my other publisher in Montreal. He would never have been bothered by me publishing with D+Q. Ever. He actually was very clear about it: if you do a book with D+Q it’s just good for me. I just felt this sense of, I was working on this book project for him, and I think there was a lot of leftover intense family stuff that I didn’t know exactly how to deal with. And the weird self-consciousness stuff got much bigger, and like a lot of artists I struggle with depression, and then I got involved in music, so basically I had too many things going on at the same time.

So this was this sort of thing at the back of your mind, going, I need to take that next step but I’m not ready now…

In all honesty, I don’t think I was ready. It was nice of Chris and so flattering of him to invite me and to see something in me that he felt I was ready to do a project. But I sort of didn’t know what story would be good enough, and then in 2009 I just came to the realization that the best story I have to tell is to get rid of this family thing. I kept feeling I kept telling the same story over and over but in these camouflaged, hidden ways, metaphorically, poetically, talking about the depression I felt related to my childhood. Finally I was like, I just need to take this huge dump and move on! [Laughs.]

Yeah, a lot of your earlier work was more metaphorical and fantastical, less realistic.

I feel that I’m done doing more fantastical things. Who knows, maybe in ten years I’ll be singing a different tune. But it’s weird, because as I was making this book based on reality, I’ve encountered people who’ve said, oh, I wish there was more fantastical elements in this. And I personally feel there’s enough fantasy out there, there are enough beautiful landscapes. In the past, I think there were two factors in making those kinds of fantastical comics. The first factor was mainly that I was terrified, because I felt I still was under this impression that whatever happened at my house when I was a kid was nobody’s business but my own. And the second factor was that I was lazy [Laughs.] My default mechanism was to draw landscapes that were more from my imagination, and that’s kind of easy to draw, because you can make your pencil go and not have to look at anything. And for this book, because I wanted it to be as close to reality as possible, I had to find images, and I had to think of what kind of tree there would be in this or that geographical place, and in some cases look at photographs too, and I personally feel a lot more complete now that I’ve done that, as an artist I feel that I can do this! I can pull it off! And I just feel like a grownup about it. Also I care way more than I used to about facts, I think that all stories deserve to be from… even if I’m making stories that are not autobiographical, that are totally coming from my head, I like the idea that there would be these facts that could anchor it to a specific place in the world.

So, how true-to-life is Susceptible?

So, how true-to-life is Susceptible?

These are all memories from my childhood. I changed all of the names. But all the events are exact or as exact as I remember them. I’ve done maybe five interviews about this and I keep saying the same thing because I don’t know how to otherwise put it: I think that real, true autobiography is pretty much impossible. But I did write down all of the stories that I remembered and that I was thinking of doing in the book, and then I crossed some of them off because they were too redundant, or they made the book feel like a total drag to read, and then… it’s really funny to think about it so casually now, because when I was working on it was really really draining and emotional…

It was emotional to read it!

[Laughs.] Yeah, it was definitely emotional to work on! So I would do one kind of harsher story, and one that was milder, and the stuff that I was most excited about drawing right after the one that was hardest to draw. It’s a bit of an illusion because it sort of make the book itself look more consistent, because from page one to page 70 you don’t see this drastic evolution in my style, that I got much better at drawing [Laughs.]

How long were you working on this?

For 2.5 years, but the first year I was allowing myself to do other things, and then the other year and a half this was my only thing I was doing as my drawing project. I went on a music tour but that was pretty much it. Like the rest of my time was just really long hours of working on the book.

“The Most Selfish Thing I had to Do”

This is a question that obviously gets asked a lot of memoirists, but was it difficult for you to present family members in a light that might be compromising, or might open up old wounds?

It’s pretty surreal to do something like this. I was agonizing a lot, especially about my mom. I kept thinking, what am I doing to her? My intention was most definitely not to hurt. Even if it doesn’t feel cruel to other people, if she read it… first of all, I have no idea whether my mom knows this book is out.

Are you not in touch with her?

No, I’m not, and so… here’s the thing. I try to protect my family in this way, that there’s a part of me that wants to protect my family, not talk about them as real people. But then there’s another part of me that’s like, I just did this book. I don’t want to be a hypocrite about it. Like, “Oh, well, you’ll never know” [Laughs.] I feel comfortable basically saying that I was agonizing because I know I’ve broken her heart numerous times, already starting a long time ago. It’s just this thing, I have this magical power to break my mom’s heart.

Well, it seems from the book that she can break your heart too.

Well, it seems from the book that she can break your heart too.

Well, it’s this cliché of this mother/daughter relationship. This book is the most selfish thing that I’ve ever had to do but I needed to do it. I could never have called her up and told her all these stories, the minute I would start to talk about it, and this is not just because of her, it’s just the way these conversations go, when things are very tender and sore in a family, you start trying to bring something really intense up and you get interrupted immediately and it just snowballs, and the only way for me to get everything out was to write a book about it. And the reason I wanted to write a book about it was not purely because of me, I was also meeting more and more people who had similar relationships with their families, it’s not straight up abuse, it’s not like Daddy’s Girl by Debbie Drechsler.

Oh God, I’m still traumatized by that book! [Laughter.]

It’s these weird nuances that I was trying to talk about, where you can come from a family where there are these really strange gray zones, and you don’t really understand why it feels so terrible to everyone involved, to the parents, and to the children, but it’s a common thing, so I felt inspired to make this book about how a family can love one another but still do some pretty traumatizing things.

The situation in the book is obviously not like Daddy’s Girl, that’s monstrous, but just thinking about a child like you’re describing yourself being in the book, vulnerable and unprotected in certain ways, it was really powerful. Even though I realized that things were hard for your mom too, being a young mother with no support and so on, it really made me feel angry!

Thanks, I guess, and at the same time, ugh [Laughs.] I was trying to be fair. But that’s the thing. Sometimes when you have an audience or a readership when you’re in conflict with someone… I’m in a conflict with my family but I’m creating this readership so I have something on them. They don’t have that. They don’t have anyone to defend them. They don’t have anyone to say what you just said to me: well, things were hard, or, your daughter is just an ungrateful bastard [Laughs.] I guess with this book I was feeling a lot of anguish about what type of difficulties, of torture, I was creating for my mom. And I just have to accept that weather or not I was going be doing the book, my mom was already feeling tortured by me. I think that no matter what you get from the book, no matter how many times someone is like, well it’s a kid, it’s a kid, you were a kid and you were treated that way, my mom was also put in this horrible situation; having a child at 19, and having to raise it on her own, and the way single moms are treated in our society is totally unacceptable. They don’t have enough help. Another thing is that a 19-year-old having a baby probably thinks it’s going to be easier than it turns out to be [Laughs.] I don’t think that many children are wanted, that’s nothing new. I think a lot of 35-year-olds have babies they weren’t planning on.

Are you in touch with your father?

Are you in touch with your father?

Yes, mostly over the mail. I haven’t seen him in seven years. He did read the book, and one good thing about that was hearing him say, “at least the parts that I’m in are exactly as I remember them.” So it was good to have that approval. And also I knew that I could be honest about him. I knew starting the book that I had his approval, whatever I wanted to do I knew him and his girlfriend would be like, “the kid needs to do this” [Laughs.]

And also, just the fact that your mother didn’t abandon you, that you lived with her, would probably make that relationship in some ways more tortured. Because maybe it’s easier when there is that distance that your father created.

It was really hard for my mom to see me getting along with my dad because he hardly put any energy into raising me… In fact, he put zero energy into raising me [Laughs,] and then to see me having this relationship with him… I think a lot of teenagers feel like they don’t belong, like they’re aliens, and to find a blood relative of yours, not just a blood relative but your dad, and to find things in common and to be able to have a real conversation, that’s incredible, and that’s something that’s been going on between me and my dad throughout my adult life. With my mother there’s so much that’s left unsaid, and with my father there’s always been this openness, where I can just say whatever I want, including when I’m angry.

You start the book with an epigraph from a Joanne Kyger poem – “but blood does bring curiosity.” What was your intention with this quote?

You start the book with an epigraph from a Joanne Kyger poem – “but blood does bring curiosity.” What was your intention with this quote?

The way I interpret it is, you’re related to this person: what does it mean? I do feel that way about everyone on my mother’s side of my family, and my dad too. I’m constantly in awe that my dad is my dad. I’m like, what? [Laughs.] But then we look at each other’s features, our faces, our hands, our feet, and clearly we are the same. On the side of my mother’s family it’s sort of a psychological link that I feel. There is this darkness that doesn’t get talked about. I don’t want to expose too many private details but I do think there are a lot of amazing crazy stories in that family that nobody talks about. I was like, I have to finish this book! Because I think there are some cycles in my family that need to be broken.

“Walking Away is not necessarily that Evil”

There’s something brave about deciding to break the cycle, even if it means not being in touch with your family.

Yeah, you just said the magical words, about not being in touch. That was a lot of what went behind making the book. There are a million movies about families that are going through something hard together, and then at the end the kid finally says something to the parents, and the parents accept it, and they’re happy, and they have this tearful embrace, and in real life, things don’t always happen that way, it’s actually quite rare [Laughs.] I wanted to have this story that’s real in the sense of, you know what, you really can’t do anything about it. Move on by yourself.

Or create your own family, or find your own partner.

Yeah. Sometimes fixing a problem, the solution can be… if you’ve tried all other things, walking away is not necessarily that evil [Laughs.] And then this other thing, time heals all wounds, that’s pure fucking bullshit. Maybe it does for some people, but… [Laughs.]

There’s a lot to be said for moving far away from your family, particularly your parents. It makes things a lot easier, in some ways.

Well, sometimes it breaks that weird umbilical cord. The thing I regret with my own relationship with my mother specifically is that something I’ve observed happening with so many of my other friends didn’t happen. I saw many of these friends who finished high school, went to college, and then when they came back for Christmas or whatever to their families, there was this new relationship. The relationship had transitioned. It was not painless, in most cases, but there was this opportunity to know your parents as this new thing. And in my case, I came back, and I was expected to go back to the room I’d been sleeping, and stay there. Continue to go to school, but come home every night, or get an apartment with my mom and just stay there. The opportunity to have a new relationship never came up.

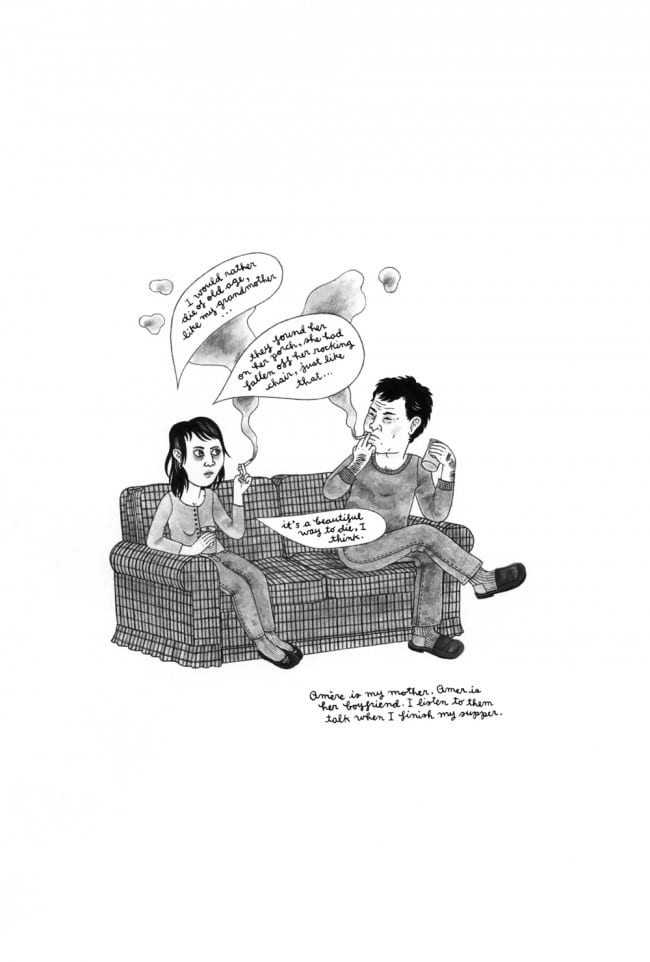

On the one hand it seemed like there was a lot of openness between you and your parents, too much openness. You were exposed to things kids aren’t supposed to be exposed to—drug use, alcohol use, sexual dalliances. But then on the other hand it seemed that your mother and your step-dad were also very strict with you.

My roles were different from those of other kids. I was expected to be more like a friend, from an earlier age – as soon as I was able to have logical conversation, I was all of a sudden a confidante, and I was expected to behave more like a grownup. It’s really funny: I was offered two extremes. I was offered to be like a grownup in some senses, and then in some other senses, I wasn’t trusted with some really simple things, like using the stereo.

Why was that, do you think?

Quebec used to be this place that was super Catholic, and while some of my Montreal friends who are close in age to my mom and her boyfriend, they had these childhoods where there were only two kids, and they’d go to the movie theater, my mom and her boyfriend came from very small villages where the church still held a lot of power. And with my mom coming from a family of 16 children, she came from a different era, and both her and her boyfriend had these values from these olden days. So while the two of them had emancipated themselves from this religious upbringing—he traveled to India, and she smoked hash sometimes, and they thought they were pretty cool people who listened to Pink Floyd—they were still like, "this is not the tone of voice you use to talk to your parents, young lady". And their idea of what an appropriate punishment would be what I could easily imagine was something from their childhood.

In one of the chapters, your mom comes and sits with you and a boyfriend, and she’s like, do you listen to Pink Floyd, and you want to kill yourself, “I’m so ashamed” [Laughter.]

Yeah, in those parts of the book I also wanted to show that I was kind of a snot, like, “oh, go away.”

I definitely identified with that. Now that I’m getting on in years and I’m a parent myself, I can totally see myself being the embarrassing mom, coming up and asking, oh, do you kids still listen to…

Belle and Sebastian? [Laughter.]

Exactly.

“I Just Procrastinate Until 3 PM”

What are you working on right now?

I’ve been getting into making porcelain volcanoes recently. The thing about this specific porcelain that I use is that it sort of collapses onto itself very easily. And so I’m trying to play with that. I can only build it up so high before it falls. So I’ve been doing things to the volcanoes to make them shoot out, all these tricks. I have made some porcelain sculptures in my house but lately I’ve been using this studio and it’s really great. One of the mad miracles of living here is I met this lady, Sue Roberts, who’s a sculptor, and she lives on the island right next to where I live in Anacortes, so I can ride my bike to the ferry for seven minutes and then the ferry ride takes seven minutes. It’s 15 minutes overall. It’s really exciting, you take a really fast boat and then you’re on the island next door, and I can work with porcelain in her studio. The great thing about porcelain as opposed to drawing is that I need to work a lot faster, and it’s never going to look like what I was planning in my head, so I just have to deal with what the clay is going to let you do.

So you’re saying it has less control than the drawing process?

Yes, probably because I’m just starting, I only started doing this three years ago, and I have so much other stuff going on that I’m definitely a novice. I don’t understand it as well as I understand the other stuff that I do.

How important is control for you in your process as a cartoonist? Do you plot out things in advance very carefully?

How important is control for you in your process as a cartoonist? Do you plot out things in advance very carefully?

I don’t think I have that much perspective on my process. I may say one thing and then somebody else who has seen me at work might say, oh no, that’s totally wrong. I saw this in a couple of places, people saying that: the line is very controlled, and I was like, really? It is? [Laughs.] But, I guess I’m really fussy or we can say anal about how I want things to be, but I think that as I’m getting older, and also as I’m doing other things, I’m excited about the improvisation or mistakes that get made. I look at it and think, actually this looks much better or more alive than it would otherwise. You do things over and over and then there’s a little quirk that happens and you’re like, I’m going to leave it there!

What are you reading right now?

There was this cartoonist in Quebec in the early 80s called Sylvie Rancourt, and she did this autobiographical comic about being a stripper, in French, called Mélody. At the time it was translated into English and redrawn by this cartoonist named Jacques Boivin, and was published by Kitchen Sink. But I’m reading the original, that Ego comme X in France just republished. And it’s incredible, because this woman had no professional training. She sort of read some Tintin, and she sort of read some Archie comics… She decided to draw her adventures as a stripper, and she’d photocopy them or print them maybe and sell them to her customers in the strip club where she worked. And the drawings are really naïve but in a really beautiful way, it’s really rare, they’re always present, their roundness; somebody said that it looks a little bit Japanese inspired, though I don’t know where she would have gotten that from. So I’m reading it now and it’s blowing my mind.

And then this other thing I’m really excited about is this woman Ulli Lust, from Austria. I think she lives in Berlin now, and she has this comic that I read in French a couple of years ago, but Fantagraphics is publishing it now in English, and I’m thrilled. In English it’s called Today is the Last Day of the Rest of your Life. It also takes place in the 80s, and it’s a brick, it’s super thick, and it’s autobiographical. It’s about how when she was a teenager, she and a friend hitchhiked from Austria to Italy, and they were these punk kids, and I feel like, as an autobiographical comic it’s mind-blowing, because the subjects that she brings into her story are things that happen to so many women that aren’t really discussed, that feeling of meeting a young guy your age and he’s basically forcing himself on you, and that awkwardness, and being this open-minded woman, and you don’t really want the guy to touch you a certain way, and these really bad things happen, and you want to be badass about it, but he basically rapes you. And it’s an amazing book, because she never ever has any self-pity, and it was kind of tricky, reading it; I read it as I was working on my book, it was kind of crazy to read something like that, because I was like, I’ll never be able to make something this good [Laughs.]

Are you reading anything that’s not comics?

I’m reading a lot of Margaret Atwood. I’m going through this Atwood obsession, I’m reading this book of interviews with her, and I’m finding it very inspiring. I think at one point Joyce Carol Oates asks her to discuss her day and Margaret Atwood is like, "Oh, I don’t know I just procrastinate until 3 pm and then I frantically start worrying about writing", and you’re so excited to read it and you’re like, oh, that’s my life! [Laughs.]

I know. You get to this age where you realize that what you’re doing—that’s the way life is. You keep waiting for this moment, you imagine it to be one thing when you’re younger, and when you become an adult you realize, I guess that’s the way most everyone is.

GC: She’s very prolific as a writer, she wrote a lot of great books, and so it’s exciting to think that… this is something’s that’s good and grounding, that people who are productive seeming have the same flaws you’re struggling with. And in her case what’s also exciting is that she didn’t start her writing career until a little bit later. She got it going between the ages of 30 and 35, which is also something I can relate to. And that’s good. I think we have this obsession with youth, and it’s getting worse now, in this digital age, everyone has to be the youngest singer, the youngest platinum-selling whatever… [Laughs.]

“Look at That, They’re all Ladies”

So you’re reading mostly stuff by women?

It’s funny; I’ve been feeling this duty to archive these comic books made by women lately. Often if I’m in a comics store and I find a comic made by a woman either in the past or from now, I’m more drawn to it. It’s not like I’m the sort of person who’s like, oh, I’m going to support sisterhood first before anything else. I just want to buy whatever I want. But lately, somehow, listing things that I’m reading and buying, I find myself going, oh, look at that, they’re all ladies.

Does it have to do with the autobiography thing? That you’re drawn to artists who are able to represent experience truthfully, and so you’re more attracted to women because it makes sense that they’ll represent experiences that matter to you more fully?

Partly. I don’t know what everybody thinks of my book, but a big chunk of the people who have given me good feedback on my book are women who can relate to it. And I assume it’s because the mother/daughter thing is not something many men can relate to. But I guess the reason why I’ve been feeling this duty to archive these women comics is, I do think that there needs to be more of a readership. I feel like it’s so easy to find an incredible woman cartoonist. I could go into a bookstore and I could find you so many women writers and cartoonists, and it wouldn’t be a big deal. But to find a group of women who are interested in comics, that’s a problem. I see some of these women’s books as masterpieces, for instance that book I was telling you about, Mélody, I think of it as this incredible thing, and also Ulli Lust’s book is a masterpiece. And I feel like, why aren’t these people more successful than they are, why weren’t they made a bigger fuss over when they were making these books I’m freaking out over? And people can be like, oh, it’s because of sexism, and I definitely think there’s a shit-ton of sexism, but I also feel like, who’s gonna read these book if none of my lady friends read comics? All these super awesome women I know are not interested in comics. Whenever I have women friends come over to my house I always put books in their hands, you should check this out, this big stack of things, and they’re always really into it.

So you think it’s a question of introduction?

Perhaps. A lot of my friends who I really admire and love and adore Kate Beaton's comics, but don’t read anything else. And I agree, Kate Beaton is rad, but once you’re finished reading this one Kate Beaton book you have you can check out some other stuff, too!