If the psyche is the moon, its dark side is the unconscious mind. It exists in perpetual shadow, its back to us; nonetheless we blindly sense its pull. The unconscious is where we keep memories, desires, and fears, both personal and cultural, that we’re unable to face directly. It’s a spooky crawlspace crammed with old possessions we don’t want in our house proper—things we mistakenly longed for, unwanted gifts, ill-fitting hand-me-downs, accumulated filth—but these relics sneak out to force themselves upon us whenever we deny them. They visit us in dreams. They influence our decisions. When we try to spot them directly, they scurry out of sight.

Because it’s dark and dangerous territory, the unconscious mind manifests itself in allegory as nighttime, underwater, underground: locales to which humans are unaccustomed and defenseless, with senses incapacitated. Creatures native to those environments sometimes act as psychopomps, leading us with confidence through the labyrinthine horrors of our own minds. As discussed in a previous column, winged animals are symbolic messengers, and nocturnal winged creatures—moths, bats, owls—often come bearing news from the hazardous world of the unknown. We reject these messages at our peril: the unconscious world is the more powerful one, and those parts of it with which we refuse an open dialogue threaten to covertly destroy our waking lives.

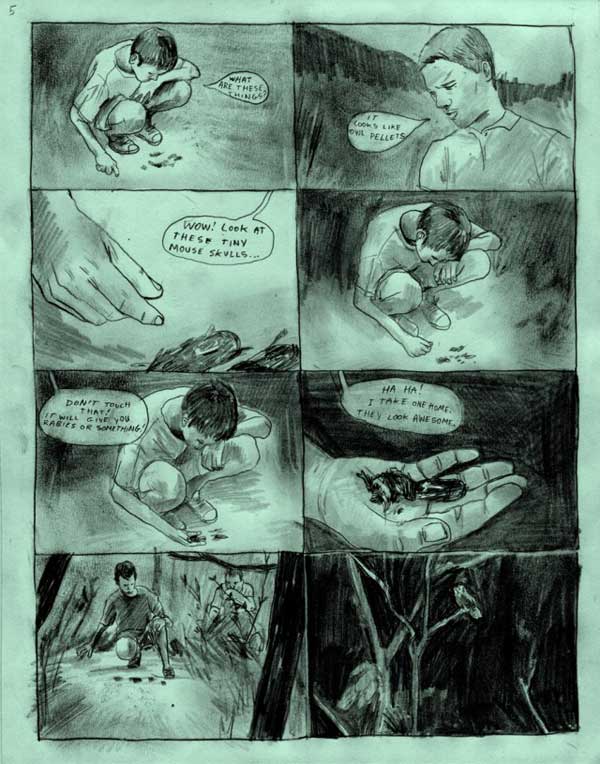

The young men who appear in Ward Zwart’s “Moon” (a 2014 Comics Workbook Composition Competition medalist) demonstrate two very different strategies for initiating the necessary dialogue with the unconscious. It’s difficult to tell the men apart—other than a short collar, not always visible, on the shirt of one, their clothes and their features are twinnish, which must be deliberate: it doesn’t really matter which is which. The collarless one (if that's a visual pun it's certainly on the nose) is eager to be submersed in a nearby pond, heedless of the oncoming twilight, pocketing an owl pellet from the forest floor. He approaches the unknown with naive alacrity, like a child yet unaware that harm can come to it even in play. This man is rewarded with an incomprehensible psychedelic vision, in which it seems that he becomes the owl himself. The soft representational style of the rest of the comic breaks down briefly here: not only do the images distort into violent abstraction, but then the paper itself shatters and shuffles, the symbolic world is broken, leaving only the Real, which defies depiction.

Throughout, The X-Files drones in the background, endlessly rerunning its own polymorphous search for hidden truth. (Stills from the show fill both endpapers, giving the impression of omnipresence.) The man in the collared shirt watches religiously, but it would be sophomoric to dismiss his obsession as slack-jawed hypnosis by the mindless screen. Perhaps, given what happened to his friend, he's right to be cautious. Perhaps without the groundwork of symbolic language to make the intangible darkness understood, exploration is dangerous, and ultimately futile.

The precarious state of mortal existence has sometimes been described in the parable of a traveler, who, fleeing a ferocious animal in a dark and dense wood, trips headlong into a pit at the bottom of which lurks a dragon. The traveler manages to catch himself on some tree roots, and these are being slowly severed by two gnawing mice, one black and one white. Unable to save himself, but equally unable to let go, the traveler clings to the roots desperately, suspended over the mouth of the abyss. He spies an active beehive just out of reach. With great effort, and having no other opportunity to improve his situation, he aligns himself so that a drop of honey can fall into his mouth.

Bees labor tirelessly until their deaths, slaving daily to make honey, volunteering their lives when they sting to defend the hive, and for this reason they often appear in a story to remind us of the virtue of hard work and self-sacrifice, the honey its luminous, longed-for reward. But in this parable, which originates with ancient Indian Buddhism, the bees represent desires, and the honey their fulfillment: though briefly pleasurable, it brings no true relief. And in an economy where hard work has been largely uncoupled from lasting reward, the symbolic role of honey must again be renegotiated.

The protagonist of Lala Albert's "Brain Buzz" experiences the swarm of bees that break out over her body and her mind as compulsiveness: as in the Buddhist parable, their slightly ominous presence suggests the anxious demands of desire. We meet the woman as she faces her own image in a reflective window, recreating an infant's first glimpse in a mirror, where it realizes for the first time its own individuality, forming the sense of lack which will eventually become the libido. Reaching to tuck her hair behind her ear (hair is another sexual symbol), she pulls away a bee. It's not aggressive, and she nervously shakes it off, but soon more bees teem around her, and her entire body buzzes with the soft vibrating heat of an industrious hive. Frantic with urgency, she rushes home to masturbate. She's almost too jittery to unlock her door.

Honey is flooding from her vagina now, an excessive product of indulged desire which only nourishes the next wave of hunger. Still unsatisfied, she texts a dormant friend-with-benefits for assistance, and when they fuck she sinks into something like a trance. She wanders in dark interior caverns, and follows the river of honey to its hexagonal delta at her neck--the same outlet the bees have been using. The woman sneaks out of her own catatonic body, which remains entombed with her lover in a thick, sticky cocoon, over which dozens of insects are crawling. The bees are not invaders, and the honey is not a disease but an inescapable truth of mortal embodiment. Succumbing to them consigns the physical form to stagnant futility, but once it's trapped the disembodied self can slip free to transcendence.

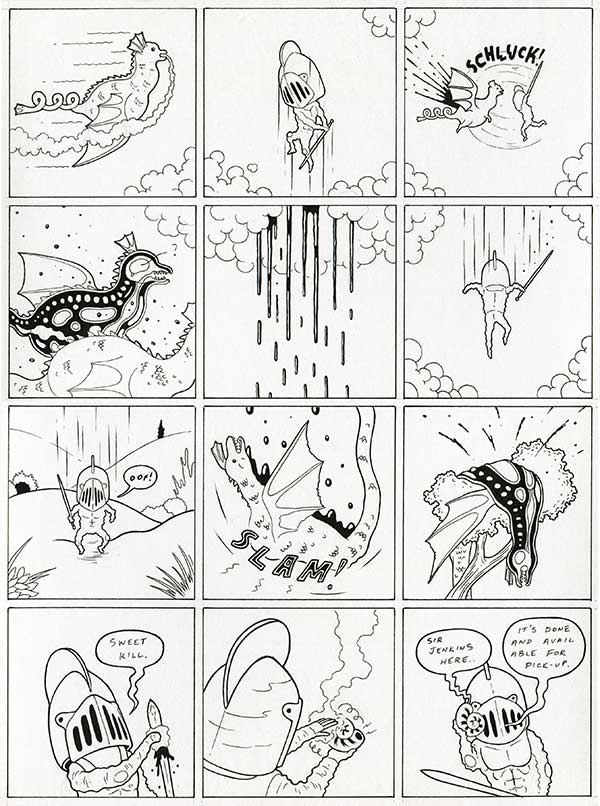

Chivalric narratives are a dramatization of the pursuit of mastery, exploring the physical and emotional sacrifices necessary to establish and maintain dominion over the surrounding environment. Hierarchical violence is inseparable from the concept of armed knighthood, the pure embodiment of “might makes right.” The very existence of an order of knights means that standards of behavior will be established by whomever has the strength, and the stomach, to exert the threat of harm over the squeamish and weak. Our culture often describes masculinity through intimidation, dominance, and emotional remove, and the story of a male knight’s quest is the story of a man navigating the predefined masculine role, one that mandates oppositional problem-solving, the exertion of will by force rather than negotiation.

To slap a veneer of respectability on this systemic barbarism, honor codes are an integral part of the romantic ideal of knighthood, and in literature a knight’s spiritual purity is often essential to his strength. Though valorous, the reprobate Lancelot could only glimpse the grail in a vision. His son Galahad, a model of beatific abstinence, was allowed to find and remove this ultimate quest object, whereupon, at his request, angels assumed him bodily into heaven. Of him, Tennyson wrote, “My good blade carves the casques of men,/ My tough lance thrusteth sure,/ My strength is as the strength of ten,/ Because my heart is pure.” But linking brute force with the diaphanous ideal of morality carries a disturbing consequence: it means that if you’re bested by a knight, he must have been a better man than you.

An untitled comic by Ben Duncan addresses the tension between these intertwined masculine ideals. One knight, Trawlins, “overcome with ferocity,” slashes a dragon in half with a single airborne hack. He means to sell it to Jenkins, a would-be knight whose swordsmanship is unequal to the fifteen-dragon-corpse ticket price of the job title, but Jenkins’ superior intellect zeros in on telltale signs that Trawlins overlooked: the dragon is a juvenile, its slaughter a crime Jenkins feels obliged to report. Affronted more by the censure than by his own misdeed, Trawlins bisects Jenkins summarily, dousing the incriminating corpses in flammable troll piss and setting them ablaze.

As fire melts the conquered flesh out of its busted hull, Trawlins muses on the trappings of the poisonous masculinity at the heart of all their suffering. He envisions Jenkins impressing a woman at a feast with trivia (the lone female figure of the comic) and clumsily wielding an impotent phallic weapon. He reviews the dragon-kill requirement for knighthood (notably, “at least 15 healthy adult males”—often female dragons are larger and more powerful, but competition among males is the purpose of this exercise), and wonders about the powerful venom he suspects trolls store in their scrota. His job isn’t easy, Trawlins concludes proudly, removing his helmet to reveal a horrifically disfigured person underneath. In a world whose foundation is masculinity defined by brutal domination, where the outcome of a battle reveals the superior soul, his scars alone prove his worth--they're the only justification he needs.