From The Comics Journal #162 (October 1993)

From the now-stilled football fields of Whitman College to the iron and cement of the Idaho State Penitentiary, from the acid-soaked bars of Santa Cruz to the rain-swept city streets of the Northwest, Dennis P. Eichhorn has led a colorful life by any account. However, unlike many who lead such lives, he was not content merely to settle down, raise some kids, and bore his progeny by endlessly repeating tales of his youthful exploits. Instead, Eichhorn took to writing his experiences down and, even more uniquely, having cartoonists illustrate the stories in comic form. Under the titles of Real Stuff, Real Smut, and Real Schmuck, Eichhorn’s history has been laid out panel by panel, rendered by a who’s who of alternative cartooning, for all the world to see. Here, in conversation with Dennis Daniel, Eichhorn ruminates on the nature of his work and worth of the examined life, as well as the responsibilities of the Sexual Revolution.

DENNIS DANIEL: You’ve got everything in your autobiographical comics: from blood, gore and guts, to everyday reflectiveness. What made you want to be so confessional about your life and to put it into comic book form?

DENNIS EICHHORN: Well, I didn’t really want to. I originally just wrote two stories for two different artists when I was an editor of The Rocket. These are artists that I had met in the course of working there, and it just happened that they were autobiographical stories. They could have just as well been prose stories — in fact, they were, initially. And then Jim Woodring suggested that I ought to put some more together and do a comic book, and since I already had two in that vein, I just went ahead and did some more. I don’t know what the sense would be to do autobiographical material if you weren’t going to be honest and forthright about it. I’m not in competition with anybody and none of the people who are doing autobiographical comics really are; everybody’s doing it for their own reasons. I’m sure that Chester Brown’s reasons are a lot different than my reasons, but I’m not sure either one of us know what the reasons really are because things like that are usually hidden. I just don’t know∂ once you get started you just carry ahead with it. I know what makes a good story, so a lot of times I try to include elements that will make it more readable and more interesting. I know the kind of stories that I like to read, so I try to stick to that school.

DANIEL: One of the things that astounds me about your stuff is how many experiences you’ve had in your relatively short life. How old are you?

EICHHORN: I turned 48 on August 19th.

DANIEL: You’re 48. Like I say, you have covered the gamut. Did you ever think, way back when, that these experiences that you were going through would make good fodder for writing?

EICHHORN: Well, at times I did, but I don’t think you realize at the time when something has real meaning. These are all things that stuck with me in my life for one reason or another. It’s the punch lines that are generally the gist of the whole story. What I’m trying to say is, I didn’t go around having experiences with the thought that someday I would write them all down. I knew at the time that I’d be foolish to sit down and write them because there’s a feedback you get when you’re writing about your day-to-day experiences and publishing them. People treat you differently and then you sort of close the door.

DANIEL: Yeah, Harvey Pekar has gone through that a lot.

EICHHORN: Sure. I do too. But it only happens in a small circle ... Only a few people know who I am. I’m not a famous individual, so I can have a pretty normal life as long as I don’t go running around with handfuls of comic books showing them to people. Very few people would ever suspect that I’ m doing autobiographical comic books unless I told them.

DANIEL: You remain a pretty consistent character throughout all of your autobiographical work. Your attitudes and your basic way of looking at life is pretty consistent.

EICHHORN: Well, I just feel like I made a lot of mistakes in my life, and this way people can find out about them and not make the same mistakes themselves.

DANIEL: There are some stories that I don’t believe are autobiographical. For example, a story like “Fatal Fellatio.” [Real Stuff #1]

EICHHORN: That is absolutely true.

DANIEL: This is true?

EICHHORN: Yeah, it’s absolutely true.

DANIEL: In the story I never got the feeling that that was you, though.

EICHHORN: Well, that’s probably because Carel Moiseiwitsch drew me real grotesquely, the way that the story made her feel. Unless they’re clearly labeled as somebody else’s story, then they’re my stories and they happened.

DANIEL: So everything that’s in Real Stuff, you are the main character, for the most part.

EICHHORN: Yeah. I can’t think of any where I’m not.

DANIEL: You wrote a couple of what I thought were fictional little stories, like the one where you actually kind of meet “Hank,” who is of course Charles Bukowski.

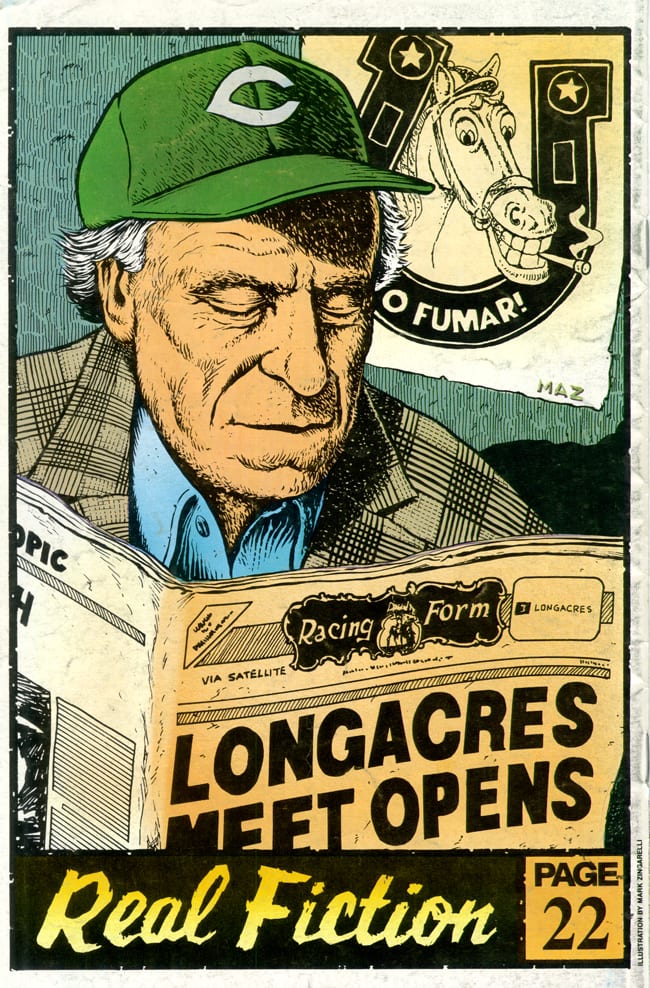

EICHHORN: Yeah, that’s prose, that didn’t happen. But on the other hand, it says “Real Fiction” on it.

DANIEL: Right.

EICHHORN: Actually, that was a story about what I would have liked to have done for Charles Bukowski. I would love to take him to the racetrack and get him in the way that I did, which was for free on the backside with all the horse people sitting around in the cafe with all of the stablehands, laying bets at the window with the trainers, and the totally different look at racing that you get that way, than what Bukowski gets where he pays his dough and goes and sits in the stands and buys a program and is part of a mob. I mean, I’m sure he loves it and it’s a big release for him, but it would be great if I could take him along for a day and show him this other thing — ride around with the vet and look in the horse’s mouth before you bet on it, and that kind of stuff, because that was something that I was able to do, but I know that there’s no way I could ever do that because he’s an unapproachable guy. I would never intrude on his privacy, and I kind of endorse his attitude. But I labeled that “Real Fiction.” There are a couple of other stories too where I’m talking to a bunch of little kids and telling them stories, and it’s clearly storytelling.

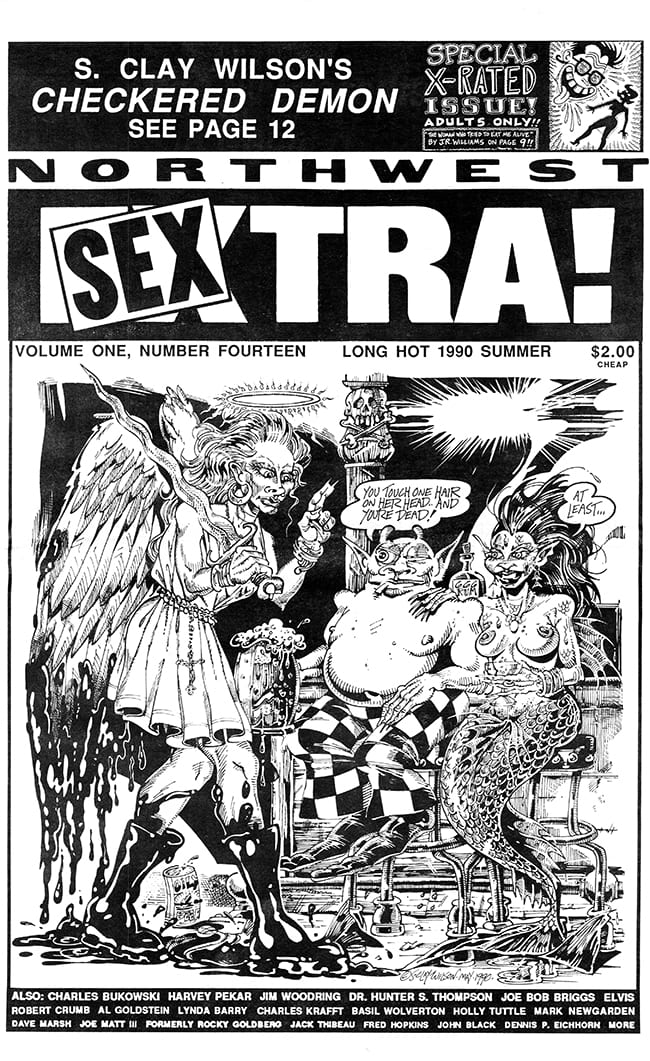

DANIEL: You’ve obviously written about Bukowski a lot, and you’ve also had some experiences with him when you had your paper, the Northwest Extra. Did you actually solicit work from Bukowski?

EICHHORN: No. What happened was, the guy who owns Water Row Books, Jeff Weinberg, deals in Beat material for collectors. So he’s got some sort of business relationship with Bukowski. Somebody sent Jeff Weinberg some copies of the Northwest Extra and he in turn sent them to Bukowski. The next thing I knew, I got this unsolicited poetry from Bukowski, because he’s kind of got a history of supporting small publications. And I think he liked the company he would be in because there were all these other really good writers — Hunter Thompson and Joe Bob Briggs and Harvey Pekar and a couple of others — who he probably feels like he’s in the same league as. It made me really feel good; it kind of indicated what I was trying to do, which was if you keep the quality up on your contributors, then you’ll attract quality contributors. That’s true. It’s not like he’s my best buddy or anything, but he’s written me a couple of letters and has sent some poems, which I passed along to Pat Moriarity for Big Mouth ... with Bukowski’s permission, of course.

DANIEL: When you’re writing your stories, in what way do you actually construct them?

EICHHORN: I do them like little screenplays. I have a panel by panel breakdown with the dialogue and the captions and the sound effects. Then I’ll have descriptive material there that provides a little universe for the artist to compose in.

DANIEL: Do you provide photographs of any of the principals that are involved in the stories?

EICHHORN: Quite a few of the artists ask for that. Some of them more so than others. People like Peter Bagge don’t need anything. But there are a number who really like to have photographs to work with.

DANIEL: Do you write with specific artists in mind?

EICHHORN: Oh yeah. Now that I’ve gotten into it, yeah, I’ll have a story and I’ll think, “Oh, J.R. Williams ought to do this one, this is perfect for him.” Or I’ll have a story that a lot of artists might hesitate to tackle and I’ll give that to Holly Tuttle because she can draw anything. Sure, you bet. There are some times, I’ll see somebody’s work and it will make me think of a story, so I’ll sit down and write it for them. I get portfolios from different artists, and sometimes I’ll look at it and it will just really ring a bell and I’ll have no trouble ... In fact, with Howard Chackowicz I wrote him five stories right away, and I’d never done that with an artist before. But other people, I’ll get their work and it just doesn’t do anything for me. I’m not saying they’re not talented, it just doesn’t inspire me to write a story. So I just shelve that and go on.

DANIEL: When you’re trying to think about experiences in your life that you want to turn into a comic book story, does it ever enter into your mind that a certain story may not be appropriate for public consumption?

EICHHORN: Well ... I try not to repress anything. There are a couple of stories that are real painful for me to deal with, and I don’t have the right perspective on them yet. And if I ever get it then I’ll include them. But I’m not really trying to make myself look good — I don’t think that I do. The only times that I’ll look good is when some artist will make me thin or give me a Peter Parker physique or something like that. I kind of shy away from the ones who do that. But that’s in terms of looks. In terms of behavior, it’s obvious that I was real troubled while I was growing up and into my adult years, and there’s no way I can avoid that so I try to include it — and it’s pithy stuff, and lot of the people are just as fucked up as I am, so they can identify with what I’m doing and the mistakes I made. It’s an exercise in anti-heroism. The really good biographical stories that I like are often that way: Charles Bukowski is such a great example of that. Henry Miller is another good example of that. They didn’t paint themselves as beautiful people. They were just real honest about what they did, and I find that real appealing.

DANIEL: Do you find that writing about something that might be particularly painful is cathartic for you in that once it’s down on paper and it’s been written about, it’s gone?

EICHHORN: Yeah, I’ve found that a lot of these stories are little tales that I have carried around with me and told to people at various times throughout my life, and once they’re actually published, I forget about them, and it’s like they never enter into my mind again. So it’s obviously clearing out parts of my mind for new thoughts. I think that putting them out there so that other people can share them with me is of course a catharsis — it’s a form of cheap self-analysis with no insights on my part. It’s changed the way that I think and look at the world, to a certain extent. I think that’s good.

DANIEL: Is it getting harder as you go on to come up with stories from your life that are worth drawing comics about, or do you have a million of them?

EICHHORN: I think I do have a million of them. I don’t see any immediate end. I know I can go through 20 issues of Real Stuff, and probably more, and I have six issues of Real Smut, plus Real Schmuck which I’m self-publishing with Starhead Comics, and the upcoming Amazing Adventures of Ace International ... then there are other stories that have been in Drawn & Quarterly and Naughty Bits and various publications ... I mean, I’m sure I’ll run out sooner or later ...

DANIEL: That’s amazing to me, because every time I read a story, I think to myself, “What the hell else could possibly happen to this guy?”

EICHHORN: There is lots that I haven’t put in yet. I don’t know though, I kind of feel like if almost anybody took a close look at their life, they’d find a lot of material there for stories and they could do the same thing I’m doing. There are a lot of people that have had more interesting lives than I have. Many people have experienced a lot of things that I haven’t. Like for instance, Tim Cahill. Let’s suppose Tim Cahill decided to get into comic books ... God, that guy would have an incredible barrage of stories, I mean, that guy has climbed fucking Mt. Everest and gone down into the deepest cave on earth; he’s driven from Tierra del Fuego to Prudhoe Bay ... What a life!

DANIEL: Yeah, but you know something? As monumental as those things that Cahill has done are, I like it to be more down to earth and real life. When I read Real Stuff, I can, in most cases, say, “Well, that could happen to me. I could have done that.” I mean, I don’t think I could have climbed Mt. Everest, but I can read Real Stuff and say, “You know, I might have done that.” I find myself in a lot of instances empathizing with you.

EICHHORN: I’m sure you’ve done things that if you thought about it, and wrote stories about it, would be real interesting to a lot of people. Then you might find you’ve got another one ... and yet another one. And then ... it doesn’t take that many. You’d be surprised. I’m not saying that I haven’t had an interesting life, but there are others who have had more. It’s just the fact that I was in this position to start working with a bunch of cartoonists. It would be pretty hard for a lot of people to do it. Plus, there’s no money in it. If I didn’t have a job to support myself, I wouldn’t be able to do this. I enjoy it. I feel fortunate to have been able to sort of fall into it. ‘Course if it wasn’t making money, nobody would go along with it. But yeah, it’s OK, it’s not limiting at all. In fact, one of the best things is that I’ve made some really good friends in the course of it with the different artists, and there is really a special link that I sometimes get with some of the people who render these stories. Some of them are really nice people. I like artists in general, so I appreciate what they’re doing. It’s a healthy way for me to meet people that I never had before. It’s just like going to a nice party and meeting a whole bunch of great people and doing things with them that are productive and uplifting. It’s great. And, as Mark Zingarelli once said: “It’s a great way to meet chicks.”

DANIEL: Harvey Pekar’s stories tend to be very basic (I hate to even use the term “mundane”), but he could talk about a very basic subject matter —

EICHHORN: He’s a very clear-headed person, though. And his thoughts are worth reading. That’s the essence of, for want of a better word, gonzo writing.

DANIEL: I won’t ask you what gonzo is. [Laughs.]

EICHHORN: Well, we’d have a tough time defining it. Bill Cardoso made it up, and I think he said it’s from the French-Canadian “gonzeau” ... But it basically is just reportage done very first person, and the thoughts of the narrator are as important as the events being chronicled. If you’re not clear-headed and don’t have good thoughts, then your reportage isn’t going to be very interesting. And Harvey is real clear-headed and he’s super-intelligent, and he knows what he’s setting out to do — the stories might appear mundane to some readers, but that’s just because they’re about everyday life instead of about some thrilling thing. I’m really inspired by his work. He’s got a handle on something, I’m not sure what it is ...

DANIEL: Do you find that his name comes up very often whenever anyone ever talks with you about your work?

EICHHORN: Oh, every so often.

DANIEL: Have you gotten into any lengthy discussions with people about how Harvey’s stuff is better than yours, or one of those types of deals?

EICHHORN: No, nobody’s really ever said that, although people like my work for different reasons than they like Harvey’s. He tends to go with realists and I like to use people who are more abstract and cartoony.

DANIEL: J.R. Williams comes to mind right away.

EICHHORN: Yeah, he’s really got a great sense of humor. He adds a lot to my stories. He’s one of the artists that really brings quite a bit with him. Whenever I have a story of two teenagers getting into trouble, I always think of him with his Bad Boys ... they’re really mean little kids. He did a funny one for issue #14 of Real Stuff, the Wildman Fischer story — I don’t know if you know who Wildman Fischer is ...

DANIEL: No.

EICHHORN: You will after you read the comic. He’s a legendary pop star in American music. He was bigger than the Beatles — that’s what he says, anyhow. You’ll know all about him when you read Real Stuff #14.

DANIEL: One thing I wanted to find out about is the Capitola Joe’s “universe” — I don’t even know if that’s the proper word, but you’re always returning for some kind of story.

EICHHORN: A lot of things happened to me there.

DANIEL: How many years were you at Capitola Joe’s?

EICHHORN: I wasn’t even there a year, it must have been nine months, and there are three or four stories I haven’t used yet.

DANIEL: Another subject that you have written about extensively is your college days, your football days. The story that really bent my head was the one where you kicked the guy’s eye out. Were you taking creative license or did you actually blind this guy in one eye?

EICHHORN: That’s exactly what happened. I used to see him riding around town on his motorcycle wearing an eyepatch after that.

DANIEL: Good Christ!

EICHHORN: And they practically gave me a medal for it. So you know, I’m just trying to tell a story of these misplaced values that we have.

DANIEL: You seem to also have a lot of interesting one-nighters or two-weekers or whatever with women.

EICHHORN: Well not that many — when they’re all in a little lump like this it looks like quite a few, but there’s not that many if you count them all up. I’ve almost mined that dry by now. But I wanted to say something that you made me think of — Mary Fleener said this when we were talking about the promiscuity and the free sex and the one-nighters — a lot of us lived through this period of time, the late ’60s and into the ’70s when it was OK to be promiscuous and stoned all the time — or at least a lot of people seemed to be. It was sort of “the good ol’ days,” in a certain sense, and she says we owe it to people to chronicle this because it was a unique time in human history. All of the things that went into LSD drug culture and the antiwar movement and free love and all of the things that are almost tired clichés now, but those things meant a lot to we who were living it, so we have an obligation to tell about it. And she does in her stories as well. So anyway, I kind of took that to heart, because I thought that was really constructive of her. In a way, that is what I am trying to do.

DANIEL: You’re absolutely right, because you can read underground comics from the ’60s and early ’70s and see many elements of this in them, but it was being written at the time it was happening. So you can look back on it and say, “This is a historical document representing a period in history — here it is 1968 and here’s what they’re writing about,” you know, R. Crumb — he comes to mind right away.

EICHHORN: That’s true, R. Crumb is the biggest inspiration for anybody who’s doing autobiographical material. I mean, he totally laid himself bare for people, and did it in a way that nobody else can equal.

DANIEL: Very angry, self-loathing ...

EICHHORN: And real honest, without really caring what anybody thought about it. And another guy is Justin Green, Binky Brown. I mean, that guy is really ... When that was published, that was quite a work of sequentialism.

DANIEL: While we’re on the subject, just talking about the comics of that particular period, R. Crumb and Justin Green, does anybody else come to mind that really, to this day, has still bent your head, and maybe even some people that you actually finally got the opportunity to work with?

EICHHORN: Sure, S. Clay Wilson and Spain are two really good examples. I’ve always really liked their work, and I got a chance to work with them to a certain extent.

DANIEL: What have you done with S. Clay?

EICHHORN: He did a cover for the Northwest Extra.

DANIEL: That’s right. Did he do the Checkered Demon on it?

EICHHORN: Yeah. And I’ve talked to him about doing a story — there are a couple of stories that I’d like to do that have bikers in them and that I think he’d really be perfect for —

DANIEL: God, yeah.

EICHHORN: But I don’t think that at this stage of my development I can afford it. The same thing with Spain. I met him and talked to him about maybe getting him to do a cover but it didn’t work out. I hope it will before the Real Stuffs have run their course. Spain’s another guy who I can’t really afford that could probably afford to take time to do a cover, but as far as the stories go, the page rate is so low that some of these people can’t take time out to do it.

DANIEL: S. Clay would be perfect for a Real Smut story.

EICHHORN: Oh yeah — in fact, there are a couple that I’d like to get him to do. But there are other people who can draw a good motorcycle.

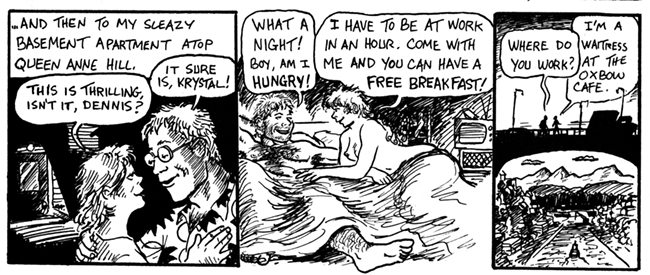

DANIEL: You’ve had some really beautiful, quiet, and reflective love stories — I’m thinking of the one where the girl says, “This is thrilling, isn’t it Dennis?” And you say, “It sure is, Krystal.” Issue #4. I think that’s a beautiful little story.

EICHHORN: Yeah, you know, she got real mad about that.

DANIEL: No kidding!

EICHHORN: Yeah. Krystal moved to France and went to mime school — I think I said that in the story. She married and had a little child. I sent her a copy of the comic and she wrote back a real frosty letter and told me not to use her any more, she didn’t like being interpreted by artists — she probably had her husband looking over her shoulder while she wrote the letter. But I disobeyed her and used her again in Real Schmuck, in Danny Hellman’s “Iron Denny.”

DANIEL: Another cartoonist that you work with is Pat Moriarity. Why did you pick Pat, who has a very cartoony approach, to draw “Death of a Junkie,” which is so utterly grim?

EICHHORN: I didn’t know exactly what approach he was going to take, because Pat can do a lot of different styles. But that was one case where an artist wanted to do a story. Pat arrived in Seattle and started working for Fantagraphics as an art director, and he asked me if there were any stories I had that he could do and I said, yeah, I’ve got a couple that were just kind of sitting there without anybody’s name on them. I gave him that one because he could go to the Seattle Center and draw the Space Needle and all that, and I just thought it would be convenient. I like the way it worked out.

DANIEL: Well, the character’s dead, and yet he draws him like some cartoon character that’s been hit over the head with a hammer. It took the sting out of it, for me. If it had been drawn realistically, I think it would have really repulsed me.

EICHHORN: I think that mirrors our culture right now — we’re becoming as desensitized to death as they are in Latin American countries, after all our years of shoving them around. And TV and the media and even comics have trivialized death, it’s part of that.

DANIEL: The “Them Changes” that you did with Seth and Chester Brown in issue #6 ... Did it take a long time for you to get the artwork from Seth?

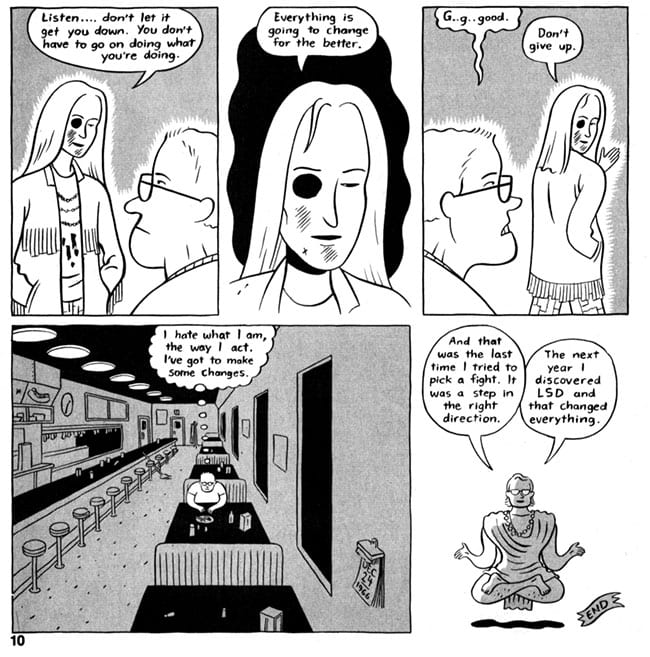

EICHHORN: Yeah, it sure did. Seth sent me Palookaville initially, and I saw it and I thought, “Now this guy is really honest about his life, this is quite a thing he’s done here.” I thought, “Well, I’ll try and be equally honest.” One of his stories was about him getting punched in the eye by some asshole on the street or something like that. So I wrote a story where I’m the asshole and I punch somebody, and then this person pulls a Christ move on me and forgives me and tells me that it’s obvious how much pain I’m in, which was true, but I had never realized it. It really happened, it just absolutely floored me. It was a beautiful thing, really a genius thing to do on this person’s part. So I sent it off to Seth and he started working on it and then he had some kind of crisis in his personal life and he just broke down and he couldn’t do any work for a while, and I know how he feels because that happened to me before — you get all wrapped up in your personal life and everything else is secondary. It just didn’t come and didn’t come, and I called up Chester Brown, who I didn’t even know, asking him what the problem was, and Chester was being real helpful. Anyway, to make a long story short, Chester actually drew the last page of that. He and Joe Matt went over and just sort of sat down and did the story. They were able to imitate Seth’s style.

DANIEL: So you’re saying that page ten in issue #6, that was drawn by Chester and Joe?

EICHHORN: Yeah. Mainly Chester, I think. But the two of them were able to ape Seth’s style. Chester’s about as good as you can get. I mean, he’s really a great artist. He applied his talents to that task and pulled it off. [Laughs.] I’ve had a couple of people have nervous breakdowns on me — he’s one, I can’t remember who the other one was. [Laughter.] Another one is Chris Oliveros. All of his artwork has got hands in it; he sent me some work, and the hands were exaggerated like crazy. That made me think of a story about hands, so I sent it to him, and he had it for over a year. I’ve got him scheduled now for issue #15 of Real Stuff and he says he’ll do it for that ... now he’s gotten Bernie Mireault to pencil it, so I’m afraid the hands will shrink a bit ... we’ll see. Another guy is Jeff Johnson, a talented artist in Atlanta. In his work hands are a predominant feature too. He reminded me of Chris Oliveros a lot. I wrote him a story about a guy getting his hand cut off and sent it to him —

DANIEL: This is again a true story.

EICHHORN: Oh, yeah. It’s about this guy, a bartender in a bar I used to frequent because I worked with the band that played there a lot. One night the owner of the bar got real pissed off at the bartender and cut his hand off with a meat cleaver. It really stopped the music, I’ll tell ya. The guy lived, and eventually came back to work as a one-armed bartender. It didn’t traumatize Jeff Johnson — he did a superior job on it, it didn’t seem to bother him at all. But if I had sent that one to Chris, I don’t know what would have happened.

DANIEL: There are certain artists who, just by looking at their work, I think they have a lot of pain. The first person who comes to mind is Carel Moiseiwitsch ...

EICHHORN: Yeah, she does have a lot of pain. She grew up in London during the Blitz; she was a little baby when London was getting bombed and she lived through that. She’s had quite a life. And her artwork has kind of carried her through. She’s a brilliant artist, one of Canada’s best known painters. Her work is unbelievable.

DANIEL: I physically felt revulsed while reading it and seeing the way she was trying to —

EICHHORN: Yeah, she captured the sordid aspect of it all. It’s a strong story. I told her this story when I first met her. She won an art contest that The Rocket hosted, so she came to Seattle from Vancouver and we met. I think she asked me if I had any good stories that would be suitable for cartoons, and I told her the story and she jumped all over it.

DANIEL: What led you off from Real Stuff to Real Smut?

EICHHORN: About the time I got to issue #5 or #6, there were two or three sex stories in each issue and somebody said, “This stuff could just as well be in Eros,” Fantagraphics’ pornography wing. I thought, “Well, I’ve got all these stories, and it’s taking so long between issues that I could be doing two titles at the same time, and if I put all the sex stories in a few issues, then it would make it easier to get Real Stuff into Canada and the United Kingdom.”

DANIEL: Have they stopped it a couple of times?

EICHHORN: Yeah, it’s been seized a number of times. So I asked Gary Groth what he thought, and he thought that was a good idea, so I went ahead with it. At first it was going to be three issues, and then it got to be six, and I’m kind of running out of material, so six is about right. So as a result, there hasn’t been any sex in Real Stuff since issue #9 —

DANIEL: Which was the killer sex issue! [Laughs.]

EICHHORN: Right. But they didn’t want to go past #6 of Real Smut — they said it wasn’t “masturbatory” enough, is what I heard. I guess I really do feel that most of the titles that Eros have published have had very little social redeeming value to them. They’re nothing but vehicles to make money off of weak-minded idiots who will buy them. I thought it would be nice to do some stories that had sex in them and also had a storyline and maybe a subtext and a moral. I’ve tried to use it as a vehicle for that, and some of my best stories have been in Real Smut. One of my very favorites ones is the one Peter Kuper did for issue #3 about Hanford, the nuclear reservation. There’s a gratuitous sex scene in there like Hollywood would put in a movie just to satisfy a certain audience. There’s a lot of information in that story, though, about what’s going on at Hanford, the pollution, etc.

DANIEL: Do you like to see yourself drawn in so many different ways by so many different artists?

EICHHORN: Well, you have an idea of what they’re going to do before they even start out because you’ve seen so much of their work. But no, my ego doesn’t get gratified so much from that. It’s more from just being able to tell the stories. There have been so many different interpretations of me — the people who have hit me the closest are Holly Tuttle and David Chelsea. Holly knows me pretty well. We’ve seen a lot of each other over the last 10 years or so, so a lot of times the body language she’s drawn is really pretty good. She’s a top talent, I think. She did a story called, “New Age Date” with me which was right on. Holly did a sex story for Real Smut #6, [laughs] that’s like a double sex story — it’s very strong. There’s a lot of great artwork in Real Smut #6.

DANIEL: Now, correct me if I’m wrong, but it seems like most of the stories are pretty much in the past. There aren’t too many that are recent. EICHHORN: Right.

DANIEL: Why is that?

EICHHORN: Because I don’t want to get too close to home. I don’t want to be writing about things that are happening today, because it affects the way people relate to you. Then again, it does anyhow, but a lot more if you’re chronicling your day-to-day activities.

DANIEL: If you wanted to, you probably could come up with some stuff that happened to you yesterday for that matter, right?

EICHHORN: Well, I do in some of these. Yeah. There are a few stories that have happened in the recent past that either have been published or will be. Like I met this guy that had a banana in his pocket all the time and he’s always in the bar drinking with his banana in his pocket. This happened recently. I asked him, “How come you always carry a banana around?” And he says, “Well, I drink all the time, and I might get pulled over by the cops, and if you eat a banana right before they give you a breathalizer test it fucks up the breathalizer, so I always carry a banana with me.” That’s pretty funny!

DANIEL: That sounds like a one-pager.

EICHHORN: It is. Yeah, I gave it to Steve Hess, a guy I’d never worked with before. He did a good job with it.

DANIEL: How many people do you think are actually reading the comic? EICHHORN: Well, I think they print 7,000 of them. The first three issues have sold out. It takes nine months or a year to sell each issue. They have orders for about half when they publish them.

DANIEL: The sales aren’t as important as the work itself. The only thing that matters is the work and how you feel about it.

EICHHORN: Oh, I agree. I’m not writing this stuff for my mother. And I’m not writing it for my lover or whoever. I’m doing this for me, and my offspring ... and it’s nice that there’s a market for it. Otherwise I’d just be sitting here writing stories and nobody would care about them but me. And I still am pretty unknown and that’s nice too.

DANIEL: Your work has absolutely had an effect on me. It was such a pleasure to sit down and read them all again and enjoy them again and know that they’re always going to be there for me to go to.

EICHHORN: Yeah, they’re like little tombstones, that’s the way I’ve always seen them. That’s the way I think of my published work, you know? They’re like the grave markers at Arlington Memorial.