Quite a lot of the critical reaction to Paying for It has concerned itself with expressing approval or disapproval of its author — either condemning Chester Brown as a creepy exploiter of women or (less frequently) celebrating his sex-positive candor. Some reviewers have engaged with Brown’s polemic against romantic love, or his argument for the decriminalization of prostitution. Everyone’s so het up over the subject of the book that almost no commentators have been able to bring themselves to evaluate it as a work of art (in sort of the same way that it’s just about impossible to get anyone to come out and admit that any book or film about the Holocaust is bad). They’re so distracted arguing about what the book claims to be about that no one seems to have noticed what it’s actually about.

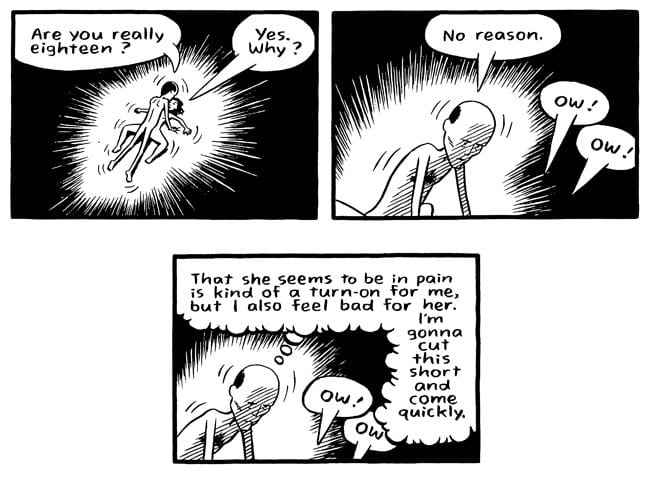

It’s some sort of testament to Brown’s fearless honesty in addressing such a taboo subject, about which there is apparently only one publicly acceptable opinion, that so many reviewers have gone out of their ways to make known their moral — and, in some cases, physical — revulsion. New York Times critic Dwight Garner, in describing a scene where Brown admits to being excited by the possibility that he’s hurting a prostitute he’s fucking, adds: “I cringe even to type that sentence.” Brown has said in an interview that he was disturbed by this incident, too, but he didn’t cringe at portraying it. And although I’m frankly made a little queasy by that scene too, I also admire Brown, as an artist, for showing it to us without the cover of some preemptive self-castigation. The unattractive truth is that men (and women) are sometimes aroused by things that are, in the light of day, creepy, disturbing, degrading or cruel. (Though I should also draw a distinction here between enjoying such things in fantasy or consensual play and actually doing them.) One of my female friends said the book “confirmed some of [her] suspicions about the male psyche.” The part of Paying for It that most resonates with me is (annoyingly) not in the book itself but elaborated in an endnote; Brown explains how, every time he used to see an attractive woman on the street, he’d imagine that there was some theoretical sequence of events that would result in her having sex with him and immediately condemn himself as a coward and a loser for failing to ask her out.

Just to get this out of the way, I’m not wholly unsympathetic to Brown’s views on the subject of prostitution. No doubt about it: relationships and dating are a mess, and you do have to wonder, at moments of low morale, whether there isn’t some other option. As far as I’m concerned, he makes a reasonable and persuasive case for patronizing prostitutes. However, Brown is a lot less interested in making a case for being a prostitute, and seems a little naive or oblivious to the realities that might compel someone to go into sex work. I’ve never patronized a prostitute, but I am friends with one, and she’s not a junkie or an indentured immigrant, she doesn’t get slapped around by a pimp, she wasn’t abused as a girl, and she isn’t in the business against her will; she enjoys her work and considers it a vocation and describes some of her relationships with clients as truly intimate. Her experience is probably not typical, but she would argue that it should be, and it deserves to be heard in the debate over prostitution. I also don’t understand why the state involves itself in consensual sexual conduct of any kind, although since prostitution is a business as well as sex, the issue is a little trickier than Brown supposes. But it’s also pretty obvious to me that, although these are all legitimate issues, none of them are the real issues with Chester Brown. [1]

What I find much more interesting than Brown’s ostensible thesis in Paying For It is the personal story here, a love story, one that the reader has to piece together for herself from inadvertent hints and clues because the author seems either oblivious to it or determined to suppress it. As with the faces of the prostitutes he draws, which are always turned away from us, covered by hair, or occluded by word balloons, there is something in this book so consistently omitted it becomes disquietingly conspicuous, haunting by its absence. I don’t know whether reviewers of Paying For It have been too obtuse or too polite to mention this elephant sitting on the divan with its feet up, but to me it seems that there’s no way to talk honestly about the book without bringing up this central deficit: It seems never to have occurred to Chester Brown to connect the fact that he’s structured his adult life to preclude any possibility of a romantic relationship with the fact that his mother was a schizophrenic.

[1] Brown’s default position on every issue is contrarian: he sees romantic love as a cultural delusion; he believes all government intervention (except the protection of property rights) is an outrageous intrusion; he sides with controversial figures like Thomas Sasz who debunk mental illness and drug addiction as legitimate medical diagnoses. This is all consistent with the worldview of Ed the Happy Clown, in which all authority figures are corrupt and suspect: the police are masked, porcine thugs with truncheons, machine-gunning convicts and disposing of inconvenient bodies; doctors smoke cigarettes over their open patients in surgery and bludgeon whimpering prisoners with pipes; President Reagan is a cranky baldheaded dwarf who’s controlled by his sultry pus-sucking wife; and divine justice proves to be just as arbitrary, cruel and beyond appeal as the kind doled out on earth. (The one exception, interestingly, is a minister, who first seems as if he’ll be a fire-and-brimstone caricature but instead preaches a sermon about love.) Reflexive mistrust of authority is probably healthier and less dangerous than blind deference to it, but it ends up being another kind of conformity; blanket skepticism is as automatic and uncritical, in its way, as blanket credulity.