Arguing over who the greatest comic book superhero is, an argument that often takes the form of who-could-beat-up-who, remains a school yard ritual to this day. But there’s no point in arguing over who the greatest comic book supervillain is: It’s Adolf Hitler.

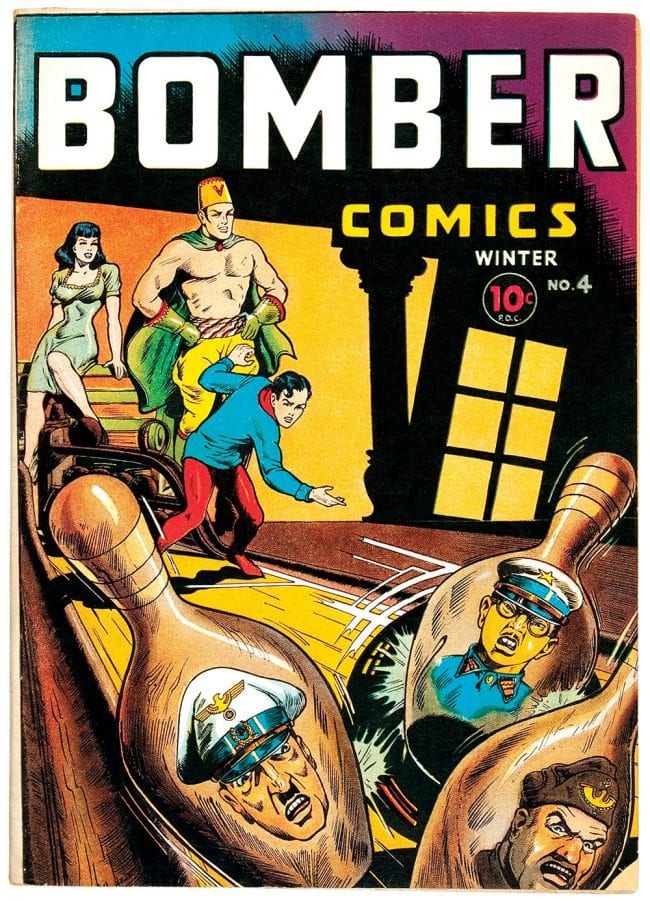

During the Second World War, the real-world dictator appeared on more comic book covers and in more comic book stories than any of the top ten, twenty or fifty villains of that era combined. Everyone fought Hitler, the Nazis, the Axis Powers, their allies and sympathizers, and, for a time, analogues of them. Not just every superhero of the early 1940s, from the household names to obscure, forgotten heroes, but even the likes of Little Orphan Annie, Andy Panda, and Donald Duck. Sometimes that fighting was abstract, like pitching war bonds or leading paper drives, but more often than not it was in punching Hitler and his cronies in the face, kicking him in the crotch and otherwise visiting cathartic comic book violence upon his caricatured avatar.

During the Second World War, the real-world dictator appeared on more comic book covers and in more comic book stories than any of the top ten, twenty or fifty villains of that era combined. Everyone fought Hitler, the Nazis, the Axis Powers, their allies and sympathizers, and, for a time, analogues of them. Not just every superhero of the early 1940s, from the household names to obscure, forgotten heroes, but even the likes of Little Orphan Annie, Andy Panda, and Donald Duck. Sometimes that fighting was abstract, like pitching war bonds or leading paper drives, but more often than not it was in punching Hitler and his cronies in the face, kicking him in the crotch and otherwise visiting cathartic comic book violence upon his caricatured avatar.

In his new book Take That, Adolf!: The Fighting Comics of the Second World War, Mark Fertig chronicles the greatest comic book conflict of all time, when the burgeoning American medium went to war against Hitler. His work is part art book, containing over 500 restored comic book covers from the era, many presented full-sized, and part history, containing a heavily-illustrated 43-page essay about the era that not only offers context to the medium’s boom years and patriotic politics, but also reveals details rarely if ever divulged in such histories.

Whether one’s interest is in the art or the history, the characters or the creators (or any combination thereof), Take That, Adolf! offers a thorough and compelling take on how the Second World War was depicted--and partially fought--at the newsstands of the Golden Age.

I recently spoke with Fertig, whose previous book for publisher Fantagraphics was Film Noir 101: The 101 Best Film Noir Posters of the 1940s-1950s, about the scope of his book, the ugliness of war-era propaganda and the immortality of the pop culture Nazis.

J. CALEB MOZZOCCO: In the terms of the sheer number of covers included, the one cited on the back cover is "more than 500." Just how many of the World War II-era covers does that entail? Does your work here include every example of Hitler-punching and swastika-smashing, or 90% of it, or half of it?

And can you tell us a little bit about the criteria you employed when choosing what to include and what not to? I admit that when I first heard about the book, I imagine a collection of covers that mimicked 1941's Captain America Comics #1, only with different heroes delivering the blow to Hitler.

MARK FERTIG: Perhaps the best way to get at the answer to these questions is to talk a bit about how the project got started.

Before I decided to write this book, I tried to buy it and came up empty. I’ve nurtured life-long fascinations with comic books and the Second World War; I learned to read from comics and have been avidly collecting them ever since, and my fascination with war goes back nearly as far. As a college professor, I’ve taken groups of students to places such as the Normandy beaches, Anzio, and Monte Cassino, to Dachau and Auschwitz. Given the key role the war played in the early development of the comic business, I imagined that there would be at least a half-dozen books already out there. Some routine internet searching turned up next to nothing—just a chapter here and there in Golden Age histories that I already had on my shelf.

I’d previously written a book about movie posters for Fantagraphics, so I put together a gallery of a dozen or so WWII cover images and emailed them to Gary Groth with a general outline of what I thought the book ought to be about. He responded immediately and told me to get to work on it. The only question he asked was when I thought I could have it finished. It’s great to work with a publisher who trusts.

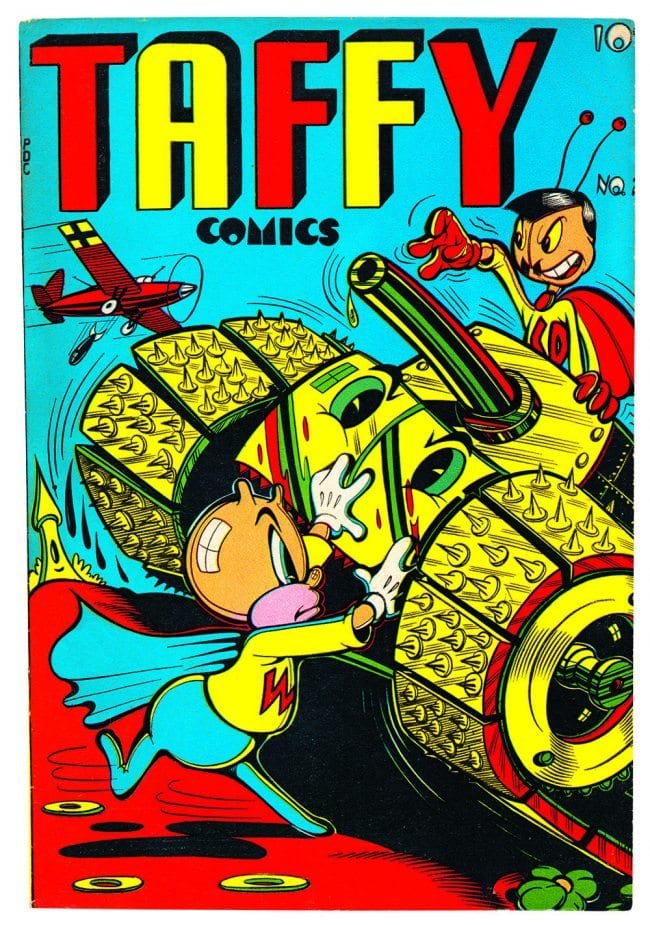

I began by trying to get a sense of just how many covers might be in play. I did countless more internet searches, then dusted off my copies of Gerber’s Photo-Journal Guide to Comic Books and examined each page with a magnifying glass, building a spreadsheet of titles and issue numbers as I went. I started to believe that the list was comprehensive when it surpassed 1,250 entries, but throughout the project I continued to discover new covers. As a matter of fact, one of the best images in the book, L.B. Cole’s outrageous cover for Taffy Comics #2, was first brought to my attention by the book’s designer, Jacob Covey, well after I had submitted everything and thought my part was finished. No one can be sure exactly how many covers directly or indirectly addressed the war, but I’m convinced that at least 1,500 and possibly as many as 2,000 deal with it in one way or another.

Narrowing the possibilities down to a manageable round number of 500 or so wasn’t difficult. As I collected images numerous organizing themes emerged, and these became the spine of the essay: pre-war covers, patriotic heroes, kid gangs, changing depictions of Hitler and other Axis leaders, racist images, war bond drives, funny animal books and so forth. There were so many different things happening on the covers for so many different reasons that after choosing the best examples of each I easily had a book’s worth of covers to set about restoring.

On the subject of that famous Captain America cover, given its prominence in the genre, I was curious why it doesn't adorn the cover of the book, which instead features a collage of various lesser-known star-spangled heroes manhandling caricatures and symbols of the Axis powers.

In the book I describe the cover for Captain America Comics #1 as the comic book equivalent of Joe Rosenthal’s Iwo Jima flag-raising photograph. It’s just everywhere — I’ve even seen it printed on canvas and sold at Target. Along with the covers of Action Comics #1 and Detective Comics #27, it’s one of the most recognizable and iconic images in the history of comics. That’s why it didn’t belong on the cover of this book. My fear was that by using the Simon and Kirby cover, potential readers might assume that the book contained nothing more than familiar content. Hopefully by showcasing lesser-known or forgotten heroes like The Shield, Captain Freedom, and Uncle Sam, along with a range of iterations of Adolf himself, readers might understand that there was a lot more going on in the comic books of the war years than they previously realized.

Most American comics fans will be familiar with the idea of Jewish-American comics artists, writers and editors using their medium to act out wish-fulfillment or revenge fantasies against Hitler and the Nazis, but I found your phrasing in the "Building Toward War" section interesting. You wrote that, "They began to understand that their creations might be used to warn the public about Hitler and make a dent in America's pervasive isolationism." The idea of pre-War comics warning American youth about the war in Europe seems fascinating; do you have any sense of how effective that warning was? Did the comics of 1940 and '41 convince many readers that U.S. involvement was inevitable, or desirable?

It’s difficult to say to what extent pre-war comics swayed public opinion or actually convinced anyone that American involvement in the war was inevitable, in spite of how much an agenda-driven publisher such as Timely’s Martin Goodman wanted to do so, because the larger domestic zeitgeist of the late 1930s and early 1940s was already all about war. Life magazine covers from 1939 showed images of Japanese soldiers, German naval vessels, and British ack-ack gunners. The United States began drafting young men into the service in September of 1940, the Lend-Lease Act followed soon after.

Naturally there was significant opposition to this rising tide of nationalism from a large segment of the public who didn’t want to see America involved in another catastrophic foreign war, including many on the political right who denounced FDR as a warmonger. It would have been easy for an ostensibly children’s medium such as comic books to simply avoid the war altogether, but given that by and large it didn’t, it’s apparent just how motivated the predominantly Jewish-American creators were in getting the word out about the threat posed by Hitler and Nazi Germany. Who knows how far they actually moved the needle? I think it’s enough to recognize how hard they were trying.

I think we also tend to imagine that the comics industry was all-in from the get-go, but you note that superhero comics sort of eased in to direct engagement with Nazi Germany, using swastika-like symbols, being coy with unnamed foreign dictators and countries, or giving them pseudonyms. What accounts for that reluctance—was it political sensitivity, or the relative newness of the medium and the genre, or both? And where would you identify the turning point between drawing weird X-symbols on covers vs. swastikas? Was it the success of Captain America, or the attack on Pearl Harbor, or was it more gradual?

Given the lens of history and what we now know about the Nazi regime it’s easy to assume that comic books would have jumped right in and started pounding on Germany from the get-go, but the typical superhero stories of the late 1930s featured domestic villains who instead reflected the dreary realities of life in depression era America: racketeers, slumlords, and crooked politicians. But soon enough the looming war in Europe and tensions with the Japanese replaced the Great Depression as the central preoccupation of American life, and comic book villains quickly embodied the change.

And yet, despite creators’ desire to spread the word about Nazism, it wasn’t a forgone conclusion in the years and months leading up to Pearl Harbor that we would go to war with Germany, or that we would even go to war at all. This period of uncertainty led all of those pseudo swastikas, imaginary countries and dictators with names that only sounded like Hitler. Readers were gobbling up war stories, but publishers had to be cautious. What would happen if we didn’t go to war after all? In one oft-told industry anecdote, Martin Goodman swapped Hitler’s name out of a story at the eleventh hour because he somehow imagined the German dictator would take him to court.

Any skittishness that publishers felt vanished in September 1939 when Germany invaded Poland and the war in Europe officially got going. Even if the United States never got into the actual fighting, Nazis were fair game because they were at war with our allies, Great Britain and France. Creators rushed to get swastikas onto their covers and real Nazis into their stories. MLJ’s Top Notch Comics #2 was first, followed a month later by Timely’s Marvel Mystery Comics #4. By the end of 1940 the kids of America were learning all about the Battle of Britain through their comic books, and Martin Goodman couldn’t get Captain America Comics #1 out fast enough, because by then he was terrified that Hitler would be dead before the issue reached newsstands.

How difficult is it in 2017 to engage with the art collected herein? You repeatedly mention the racism prevalent in the comics at the time, not only in the depiction of demonized, dehumanized Japanese, but also of African-Americans. I imagine many modern readers will need to do a bit of mental gymnastics when it comes to decoupling the racism of many of the images from the rest of it in order to find value.

The value in these comics lies in the truth they tell about the America of the war years, a truth that is sometimes overshadowed in our pop culture reverence for the American fighting man and the “greatest generation.” The racism found in the comics, movies and radio programs of the period is as ugly as it is ever-present, so it couldn’t be ignored.

I doubt anyone would have noticed if I’d omitted something as obscure as Dell’s The Funnies #64, but it was on newsstands in 1942 and so I needed it in the book. And if I’d not mentioned Fawcett’s Steamboat, then I couldn’t tell about the schoolkids who were horrified by the way the he was depicted and actually managed to do something about it. That’s a story worth knowing, particularly because we seem to have made so little progress on race in the seven decades since the war ended.

I really hope that readers don’t try to decouple the racism from the images or just look past artwork that offends, but are instead reminded how glaringly badly the country treated groups of Americans who, ironically by means of the war, proved that their work ethic, courage in battle and love of country was unsurpassed by anyone.

Another thing I learned in your book that surprised me was that in 1943 the Writers' War Board started trying to influence the comics of the period, and they pushed publishers to work even harder to further dehumanize the enemy through their depictions. That would make the line between government propaganda and a more innocent, or at least diffuse, advocacy on the part of creators awfully blurry. It's also a little bizarre to think people reviewing the comics covers featuring bestial Japanese and essentially saying, "Well, this is a good start, but could you maybe make this more racist?"

And yet that’s how it actually happened!

The WWB was one of the big surprises of my research—I’d never heard of it before I began the project. If we take a step back and look at the First World War, many Americans believed that they had been lured into fighting by government propaganda. A generation later, FDR needed the full support of an already suspicious public, so he avoided overt propaganda in favor of a “strategy of truth,” while relying on unofficial volunteer groups like the WWB to craft and disseminate the kinds of messages that the government couldn’t.

When Hitler put London under the Blitz, Americans were first in line to condemn the indiscriminate strategic bombing of civilians. But as the war ground on and on and the Allies came to believe that strategic bombing (and ultimately the atomic bomb) was needed to hasten the end of the war, Americans had to be convinced that regular Germans were as responsible as Nazis for starting the war, and that the Japanese were little more than insects. Comic books were blunt, crude, and lowbrow enough to dodge serious scrutiny or criticism. And because practically everyone in the country was reading them, the WWB saw them as an ideal propaganda tool.

We talked a little about that famous Captain America cover, and I did want to ask you about the good Captain, as he's an exemplar of this era and this type of cover. As you noted, he wasn't the first patriotic superhero, and he was followed by scores of imitators. What made him different, to the degree that he's starring in movies today instead of The Shield or The Fighting Yank or whoever? I think we tend to assume it was simply that Jack Kirby and Joe Simon were just so much better at the game than so many other guys; is that it, or are there other factors that lead to Captain America's lightning-in-a-bottle quality?

I’m sure there are a lot of reasons why Captain America has managed to stand the test time, but my cynical self wonders if it’s just because he’s a Marvel property. It was Captain America who reemerged in Avengers #4, not The Shield or Captain Freedom. If those characters belonged to Marvel, we might be talking about them instead. In spite of that landmark first cover, the amazing Simon and Kirby pages that followed, and the chart-busting sales figures, Cap was put on ice in 1949. Had he not been resurrected by Lee and Kirby fifteen years later, it’s possible he’d be forgotten today.

Still though, that origin story makes me think otherwise. Captain America is, without a doubt, the most appealing, most wish-fulfilling character to come out of the war. I’ll quote Steranko once again, “He was the American truth. The face unrevealed behind the mask was ours.”

Superheroes were around for a few years before the United States entered the war, and they are obviously still around now, but could you imagine the comic book superhero without World War II? The war obviously played a huge role in the development of the genre, but is that role inextricable?

It’s definitely not inextricable. After all, only a handful of superheroes survived the war. Superman, Batman, and Wonder Woman managed to carry on for DC, though The Shield had been shoved off the pages of MLJ comics by Archie Andrews; Stan Lee and Martin Goodman threw in the towel on Captain America in 1949. Fawcett determined that Captain Marvel’s lagging sales no longer warranted defending their copyrights against DC, so they agreed on a settlement and got out of comics altogether. Other superheroes went into an extended hiatus; most of them simply vanished forever.

Audiences were jaded by all that death, the atomic bomb, and news of what had been done to Europe’s Jews—guys in tights suddenly seemed childish and silly. The rise of the superhero comic had been so bound up in the war that once the fighting ended, nobody knew what else to do with the characters. Wartime comics were almost exclusively plot-driven, with minimal character development. Superman and Batman had once been New Deal ass-kickers; now they were uptight squares. The world at the end of the war had grown up; superheroes comics needed to grow up too, but the writers and artists who had been banging out the stories as fast as they could since the late 1930s weren’t ready to do it. So, readers moved on. Many developed a grim fascination with lurid crime and horror comics; others gravitated to Archie and romance titles; still more went for westerns. Only Donald Duck was as bulletproof as ever. For a while it looked like superheroes would be remembered as a fad of the 1940s.

Then the generation that fought the war started having kids—tons of kids—and remembered how important the superhero comics had once been to them. Their nostalgia for comics, coupled with a surging youth-oriented consumer culture, reignited an interest in superheroes. Superman got his own television show. DC brought back the Flash then launched the Justice League. Marvel dove in shortly thereafter with a healthy dose of angst—you know the rest. In the end it wasn’t the superheroes who saved themselves; it was the generation who fought and won the war, and read a lot of comic books while doing it. They may have moved on from comics, but they didn’t hesitate to encourage their children to start reading them.

One of the fascinating things about this era of comic book history is that it is unique; we would never again see comic book superheroes taking a side like this in any of the many wars that followed, and, in fact, it's almost impossible to imagine comic book covers going to war now like they did then. Do you have a sense of why that is? Was the nature of the war, the new-ness of the comic book, the absence of television, the mores of the 1940s?

The scope of the war and the many ways in which it dominated American life is almost impossible for anyone who wasn’t alive at the time to imagine. Blackouts, air raid drills, rationing and scrap drives defined daily life from coast to coast. Women entered the workforce to replace the men who left to fight. Kids practiced identifying enemy aircraft, planted victory gardens, and donated their comic books to paper drives that they organized themselves. No family was left untouched by the fighting; every heart skipped a beat at the sight of a Western Union uniform.

When General Eisenhower told the servicemen who land at Normandy that “the eyes of the world are upon you,” he wasn’t kidding. As news of the invasion reached home the country literally shut down. Banks, schools, and shops all closed as Americans went looking for the nearest radio. Movies, songs, radio shows, and comic books all focused on winning the war. That such a global conflagration could happen again in the era of nuclear weapons is unthinkable.

It’s also important to recognize that comic books now occupy a markedly different place in world popular culture; comic book movies, television shows and merchandise generate billions and billions of dollars each year for conglomerates like Time Warner and Disney. It’s difficult to imagine that in this day and age they’d be allowed to take a side.

In your research and work in making this book, did you encounter a particular artist you were previously unfamiliar with whose work you appreciated, or perhaps appreciated in a new light? Personally, I was only vaguely familiar with the name Alex Schomburg before reading Take That, Adolf! and now I could stare at his drawings of The Flaming Torch and Toro all day.

It wasn’t any one artist that got to me --though Mac Raboy, who did wonderful Captain Marvel Jr. and Master Comics covers, has skyrocketed in my esteem)--it was the way the comics were made.

Like many others, I grew up believing in the Marvel bullpen—artists hunched over drawing boards in a big room, typewriters clacking away in the background. As a kid I thought that if I could make it to New York City I could sneak into the Marvel offices and see it all happening in one place. Comics may not have been made that way, but the packagers of the Golden Age came closest. Of course most of the packaging shops had more in common with a factory assembly line or even sweatshops than they did with my imaginary Marvel bullpen, but they were where most of the greats got started.

There’s something magical about being young, broke, full of dreams and there at the beginning of something. My favorite comic book story of all time is the one about how Charlie Biro, Jerry Robinson, Bob Wood, Mort Meskin and a bunch of their pals spent an entire weekend hurriedly banging out the 64 pages of Daredevil Battles Hitler, with nothing to eat and a blizzard raging outside, just so publisher Lev Gleason could get his hands on a bumper crop of newsprint. While working on Take That, Adolf! I must have stumbled across that story in a half-dozen places, and was floored by it every time.

I was wondering if you had any thoughts about why Hitler and Nazis in general became such pervasive comic book villains, to the point that heroes are still fighting Nazis in various forms today, and, in a sense, never stopped fighting Nazis. There's the obvious reason, of course, with Hitler perpetrating the greatest crimes of the 20th century, but characters as diverse as Captain America and Hellboy are still fighting Nazis today, and much of Marvel's multi-media franchise is built around the fight against the crypto-Nazi organization "Hydra," which use elements of Nazi iconography.

Nazis are great fodder for pop culture entertainments because they offer such narrative economy. As soon as we see that swastika we know everything we need to know—no wasted panels, paragraphs or minutes of running time. There’s also no risk of readers or viewers gaining sympathy for the Nazis and switching over to their side; it’s one less thing writers have to worry about. What’s the best thing about the movie Die Hard? It’s Hans Gruber. Alan Rickman is so good in that part you wish he’d escaped and come back for the sequel. Half the audience was cheering for him. But nobody ever watched Raiders of the Lost Ark and whispered to the guy in the next seat, “I hope the Nazis win…”