For Muhammad Ali, it was the right comic at the right time. As Chicago writer Jonathan Eig recounts in his acclaimed biography Ali: A Life, the young boxer, then named Cassius Clay, was standing outside a skating rink in his hometown of Louisville, Kentucky, when a member of the Nation of Islam approached him with a copy of the newspaper Muhammad Speaks.

The man who sold him the newspaper — “a black brother dressed in a black Mohair suit, white shirt and a black bow,” as Ali later remembered him — hoped to convince Ali to go to a meeting. Said Ali: “But I had no intention of going to any meeting. But I did buy the Muhammad Speaks paper. And [one] thing in the paper [made] me keep the paper, and that was a cartoon.”

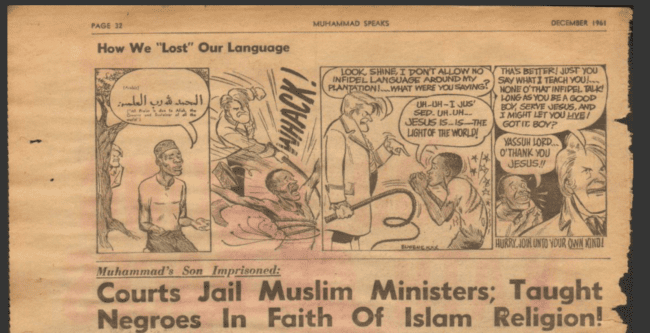

Not just any cartoon. In the list of cartoons and comics that changed history — think Benjamin Franklin’s "Join, Or Die" or Thomas Nast’s “Boss” Tweed caricatures — the four-panel comic "How We 'Lost' Our Language" in the December, 1961, issue of Muhammad Speaks is certainly more modest and lesser known. Yet its influence has been widely felt. By introducing Ali to the Nation of Islam, it not only helped shape the future of sports. It also changed the wider culture when Ali emerged as an outspoken political figure who championed black rights and protested American military involvement in Vietnam.

Years after the encounter at the skating rink, Ali would remember nearly every detail of the comic. In a letter that Eig uncovered in his research, Ali described the story: In the first panel, a plantation overlord comes across an enslaved man, dressed as a Muslim, who is saying a prayer that is written in Arabic script. The overlord whips the man and demands to know what he was praying. The man, cowering and in pain, lies to the overlord, saying that it was a Christian prayer. The overlord is satisfied and tells the man he might let him live. The comic's title is bitterly ironic.

“And I liked that cartoon. It did something to me. And it made sense,” remembered Ali.

The cartoonist behind “How We ‘Lost’ Our Language” was Eugene Majied, whom Muhammad Ali would later praise with characteristic bravado as one of best illustrators in America.

Yet Majied remains relatively unknown in comics. Born in 1926 in Spartanburg, South Carolina, as Eugene Franklin Rivers, he signed much of his Nation of Islam work as “Eugene XXX.” When he died in 2005, he would be eulogized as Eugene Rivers. He also drew under the names “Frank Lee” or “Lee,” but did his most prominent work under the name Eugene Majied, which is the name that will be used in this article.

Majied’s parents were both college-educated, and his father was principal of Spartanburg’s only high school for African-Americans, says Eugene Majied’s son, Eugene Rivers, a Boston-based activist and Pentecostal minister. Initially hoping to be a painter, Majied studied art at the School of the Museum of Fine Arts, Boston, before serving in World War II. Following the war, he moved to Chicago, where he supported his family by working as a janitor in a local department store.

Majied’s daughter, Genelle Majied, recalls that her father was unsatisfied with his life and had started drinking heavily. Yet he also enjoyed drawing chalk portraits of family members and faithfully followed the newspaper comics. “When I was a little girl, he was always giving me the funnies to look at. Nancy by Ernie Bushmiller, Steve Canyon.” Majied’s wife encouraged him to return to art, and he found work at Chicago’s black-owned newspapers, including The Chicago Daily Defender. At the Defender, Majied was part of a “groundbreaking period when it was the only Black-owned newspaper to employ an art department of six artists simultaneously,” according to Tim Jackson’s groundbreaking book Pioneering Cartoonists of Color. Among Majied’s fellow artists was Jay Jackson, best known for his WWII-era military comic Speed Jaxon. Majied also found work at the Chicago Crusader, according to his daughter.

Majied joined the Nation of Islam and would gain his largest readership through Muhammad Speaks, where he worked closely with Nation of Islam founder Elijah Muhammad, remembers Majied’s son, Eugene Rivers. “When I went to see him, he would design the newspaper and take it to show the old man, Elijah Muhammad, and he would look it over and put his initials on it, and it would go to print.”

In addition to designing Muhammad Speaks, Majied published work that ranged from single-panel cartoons that preached self-sufficiency to the early-1960s comic strip Lazz, in which the title character might mock the non-violent approach of Martin Luther King, Jr., to his girlfriend's delight. In one political cartoon, Majied depicted Uncle Sam as a divided Dr. Jekyll and Mr. Hyde who insisted, “I am good!”

“He had such a biting wit, especially when satirizing the black bourgeoisie and their failure to do anything for the black community,” says Eugene Rivers. “He was a movement artist. He’s in the middle of these debates that are still affecting the course of black politics, and he gave artistic voice to the debates. Like Emory Douglas of the Black Panther Party, he was the guy for the Nation of Islam.”

When Ali encountered Majied’s comic, the boxer couldn’t have known that the cartoonist was a fan of his, as well. The Nation of Islam forbad watching or participating in sports, but Genelle Majied remembers that her father broke the rules to listen to Ali — then Cassius Clay — fight Sonny Liston for the championship in 1964. The cartoonist and the boxer became friends, with Majied once taking his daughter to meet Ali.

Working closely with Elijah Muhammad, Eugene Majied also illustrated some of the most controversial positions and actions of the Nation of Islam. Most notoriously, these actions included threats leveled against Malcolm X following his 1963 break with the Nation of Islam. In 1964, Majied drew “On My Own,” which showed the severed head of Malcolm X bouncing toward a pile of skulls. In case anyone missed the point, Majied added devil horns sprouting from Malcolm X’s head. The cartoon earned Majied the description “brilliant but cruel” from Malcolm X biographer Peter Goldman. Malcolm X was assassinated the following year; three members of the Nation of Islam were convicted of the killing. One confessed to his role in the assassination but the others maintained their innocence, and recent scholarship has prompted calls to reopen the investigation.

Working closely with Elijah Muhammad, Eugene Majied also illustrated some of the most controversial positions and actions of the Nation of Islam. Most notoriously, these actions included threats leveled against Malcolm X following his 1963 break with the Nation of Islam. In 1964, Majied drew “On My Own,” which showed the severed head of Malcolm X bouncing toward a pile of skulls. In case anyone missed the point, Majied added devil horns sprouting from Malcolm X’s head. The cartoon earned Majied the description “brilliant but cruel” from Malcolm X biographer Peter Goldman. Malcolm X was assassinated the following year; three members of the Nation of Islam were convicted of the killing. One confessed to his role in the assassination but the others maintained their innocence, and recent scholarship has prompted calls to reopen the investigation.

In his later years, Majied returned to South Carolina, where he worked as the chief artist for The Greenville News. Eugene Rivers remembers his father during this time as being a solitaire individual who liked reading and jazz, and “had no patience with frivolous people.”

The largest Nation of Islam organization is now headed by Louis Farrakhan. It remains controversial. The Southern Poverty Law Center tracks it as a hate group, citing anti-white, anti-Semitic, and anti-LGBTQ views. Others dispute this classification, seeing the group as mainly championing the same values of self-sufficiency and self-defense that typified most of Majied's work. Rivers, who named one of his children “Malcolm,” recalls that his father would turn away from conversations about his experiences with the organization.

“I asked him about the assassination and what that looked like, and how early did he know things weren’t going well for Malcolm. He wasn’t going to touch it. My sense is he had regrets, that he had made some bad decisions and he completely withdrew from the whole thing. Almost like a military guy who had a bad experience. He just knew too much.”

When Majied died in 2005, The Greenville News eulogized him as a social realist painter and artist. Muhammad Ali died eleven years later, in 2016. For many, the 1978 DC comic book Superman vs Muhammad Ali might be remembered as the most remarkable comic connection to the boxer’s life and career. But as Ali biographer Jonathan Eig notes, it was Eugene Majied’s four-panel comic about slavery that started things off. “It completely changes the course of his life, because as he’s rising to fame as a boxer, he’s getting more and more engaged in the Nation of Islam and realizing this religion offers him a new way of looking at the world. He doesn’t have to accept the white man’s terms for living in America.”