EMMERT: We’ve been mentioning your ongoing strip, Dykes to Watch Out For, I wanted to talk to you about it. You’ve been working on that biweekly comic for about 25 years now, right?

BECHDEL: Almost. Twenty-four now.

EMMERT: Could you talk about how you got started with this lifelong project? How that all came about?

BECHDEL: Well, everything I do is very organic, very much a part of my personal life. Like meeting some idiosyncratic need of my own. Fun Home was just my deep desire to tell that story. Dykes to Watch Out For was my desire as a young lesbian just out of college to see reflections of myself in the culture. I was very hungry to see visual images of people who looked like me and I didn’t see them anywhere. So I started drawing them, just for my own amusement. Actually, for a friend. I had a friend who I was corresponding with, and I started this little series of crazy-looking lesbians in these letters to her, and I just called them Dykes to Watch Out For, and I would number them. I numbered the first one “27.”

I really liked doing these cartoons, and eventually I started submitting them to a feminist paper that I worked at. I had no idea. It never occurred to me to ask for money. I mean, no one was doing anything for money in those days, anyway. But after a couple years of just doing it for fun, I did start selling it to different gay-and-lesbian newspapers, which were just starting to spring up as a forum around that time, during the ’80s, which gave me a readership and an audience. And that just continued to expand as more of these papers launched and picked up the comic strip. By the time I was 30, I was able to quit my day job and just be a cartoonist. Though of course it’s never been a particularly lucrative career.

EMMERT: That was one of my questions: When did you start actually making a living as a cartoonist? So it was around when you were 30?

BECHDEL: Yep, 1990.

EMMERT: Just out of curiosity, what other kinds of jobs did you do before you were a full-time artist?

BECHDEL: [Laughter.] My first job out of college, I was a production assistant at the American Institute for Certified Public Accountants, which meant that I did a lot of word processing and some really menial cutting-and-pasting kind of work. I got involved in newspapers at around that time, too, doing production. And that was very exciting for me, at the volunteer feminist paper. I loved learning those primitive graphic design skills, you know, waxing Photostats and —

EMMERT: Those were the days.

BECHDEL: You had a proportion wheel and an X-Acto knife and I loved that. I did eventually get a job at a gay-and-lesbian newspaper being production manager, and that’s what I did until I retired. Learning how to manage all those hundreds of pieces of information on a page, the flow of text and images together, was really useful to me as a cartoonist.

EMMERT: Where did you go to college and what was your major?

BECHDEL: I went for two years to Simon’s Rock Early College, which is now called Simon’s Rock of Bard College. Then I transferred to Oberlin. I was a combined studio art/art history major.

EMMERT: What types of papers and periodicals carry Dykes to Watch Out For now, and how many do?

BECHDEL: It’s a dwindling number. You know, the landscape has changed pretty drastically in terms of print media. At my high point, I was in, I don’t know, maybe 70 papers, almost all of them gay and lesbian. But now I’m down to maybe 40 or 50. It’s always fluctuating, I don’t really know exactly. More of those are alternative or general readership than before, but most of them are still LGBT publications.

I’m really shifting my energies to the Web and investing a lot of time and effort in my website and finding a way to make the comic strip self-sustaining online. Since I keep losing newspaper revenue. I don’t know how it’s going to go. I’m doing this sort of voluntary donation scheme, and people responded really well to it at the beginning. But in order to keep the revenue coming, I’m going to have to do some kind of pledge drive, prompting people at regular intervals to pony up. And I’m sort of loath to do that. But I totally don’t want to get into the advertising scenario.

EMMERT: Are you in some kind of a syndicate, or are you just getting the work out yourself?

BECHDEL: No, no, I’ve always done it all myself.

EMMERT: So how would you describe the typical Dykes to Watch Out For reader?

BECHDEL: Well, you know, it’s really changed over time. There’s certainly a core of lesbian readers, but it seems to be more of an ideological type now than any other demographic. People who are progressive and lead some kind of alternative life. Although I have straight white male Republican fans who write to me regularly, so go figure.

EMMERT: Interesting. I first learned about Dykes to Watch Out For through the collected comic strips, and it looks like you started doing that about 1986. At that time, you were working with Firebrand Books, but know you’re being published by Alyson Books. What happened there? Did Firebrand go under?

BECHDEL: Well, Firebrand went through a big transition. At first, it did go under, and then it got sold. It’s so complicated, I don’t even quite grasp what happened. But it is still in existence. I did my last two Dykes to Watch Out For books with Alyson, though, and not Firebrand, basically because I have an agent now [laughs]. I’m a little savvier about how to do these things. And Alyson simply outbid Firebrand for the book. That’s why I went with them. I don’t what’s going to happen in the future. It’s getting time to do a new collection, and I’m kind of waiting to see where the chips fall after Fun Home.

EMMERT: Getting back to Dykes to Watch Out For, it certainly has a wonderful cast of characters: Some of them are what I would consider sort of lesbian archetypes. How did you develop the characters?

BECHDEL: They’re all aspects of my own self. I was very young when I started this, and I’d heard the thing, you know, that you can only write about what you know. So I said, “OK, well, then, I’ll make one of these characters kind of like me.” So I began with this character Mo, and she was this young, white, middle-class, marginally employed lesbian. I intentionally made her not look like me, but I don’t know what I was thinking, because she really does look like me. Or maybe I look like her. [Emmert laughs.] I started with her, and some of the characters are just pretty stock. There was her foil, Lois. Mo and Lois were the first characters I introduced. I didn’t give a lot of thought to it: I didn’t know what the hell I was doing. I just made it up as I went along. But each character, as I introduced her, I knew that I had something in common with her.

EMMERT: You were saying before that you would work two weeks on your memoir, two weeks on the strip. Because you use political references so much in Dykes to Watch Out For, does that kind of complicate the process, ’cause you can’t really do them ahead of time? I know some daily strips people will crank out a whole bunch so they can take a vacation, or something like that.

BECHDEL: Yeah, no, there’s no way I can do that. And the news cycle kind of exacerbates my tendency to do things at the last minute. But really, the longer I can wait, the more current the strip will be when it hits the newspapers. And I love that timeliness factor. It’s very important to me for some reason. It’s always been difficult, because my strip is biweekly, not weekly, and many of the papers are monthly, so usually stuff ends up coming out way late. And that excites me about the Web, more, too, because that can be absolutely

instantaneous.

Although it takes me a long time to draw. The writing takes me a long time, but then it takes me at least several days to get a strip illustrated. Other editorial cartoonists have a much looser style and can really turn stuff around immediately, but I’m not quite that fast. But that’s OK. I mean, the strip is a hybrid, you know. It’s part editorial and part soap opera. [Emmert laughs.]

EMMERT: So the point at which you’re finished with the strip, how quickly does it usually get published? Within the next couple of days, or —

BECHDEL: No, longer than that. Especially because I do two at a time, one of them is always delayed. So by the time they get in the paper, they’re at least a couple weeks old.

EMMERT: It was interesting, as I was reading back through all the strips, just to follow the course of the politics from that point ’til now. You know, the previous Bush, and what he was doing, and now what we’re doing. It’s just like, “Ooh, there’s déjà vu here, it’s a little scary.”

BECHDEL: I know. Like I did a strip in, like 1987, where Clarice, who’s a lawyer, was speculating on how Arnold Schwarzenegger was going to be president one day. [Emmert laughs.] God, I thought that was ridiculous.

EMMERT: I saw that. I have to admit, it was like “Whoa!” Chills went down my spine. A little scary. Who knew?

BECHDEL: But the other thing about having it be biweekly and not more frequent is that it makes me assess more carefully what events in the news are worth mentioning, because a lot of them do really disappear. So I have to always be thinking about what really matters, what’s really important.

EMMERT: Right, yeah.

BECHDEL: But sometimes I guess wrong. [Laughter.]

EMMERT: How do you make the decisions about the current events to cover in the strip?

BECHDEL: I try not to focus too much on the vicissitudes of elections and day-today stuff in Washington. Those things would be old news before I even got my pencils done. What I try to do is try to identify the larger forces and trends underneath surface events. Like what the Bush administration is doing to the Constitution. That’s much more fundamental — and, unfortunately, lasting — than Dick Cheney blowing away his hunting buddy. I haven’t done any Dick Cheney shooting cartoons at all. I haven’t even done any Mary Cheney pregnancy cartoons, but I suppose I should get on that. I cover less specifically gay material than I used to, but again, I try to keep identifying the larger, more pivotal issues, and work them into my story. Like gay marriage, though I’m getting a little weary of that particular topic.

EMMERT: I imagine that you probably have some real rabid fans of the strip. Do you receive advice or storyline ideas from them, and do you ever use them?

BECHDEL: I do receive lots of advice, and lots of storyline ideas, and sometimes I do use them.

EMMERT: Can you give an example?

BECHDEL: I posted a strip maybe two months ago, in which I had made some mistakes. My readers caught that I had gotten someone’s name wrong. I had this very marginal character from years ago who reappeared. And people actually got their books out and looked it up. [Emmert laughs.] It’s too complicated to really explain, but one character — she was half of a couple, [laughs] and her name was Liz, and the other half was named Beth, and of course, that’s essentially the same name. Then someone on my blog said, “Wouldn’t it be funny if Liz and Beth had a little girl named Elspeth?” Which is also the same name. So I totally used that in the next episode. Actually, I guess I should also mention here that another person on my blog asked if I was making an homage to Eric Orner, who has a lesbian couple named Liza and Beth in his strip (The Mostly Unfabulous Social Life of Ethan Green). Which I wasn’t — I was just unconsciously ripping him off.

EMMERT: I suppose the possible break-up of the couple of Clarice and Toni has been a hot topic with your fans.

BECHDEL: Yeah, you know, I can’t even read a lot of the e-mail and stuff, because it’s overwhelming. People have surprisingly strong feelings about it. I try to read enough to get a sense of popular opinion but not so much that I get really swayed by it. But yeah, people are really weighing in on that one.

EMMERT: I can imagine, after them being sort of the enduring couple of the strip, to have them break up is probably very difficult for some folks.

BECHDEL: I can’t tell you how deeply it pleases me that people give a shit. They really care. That’s amazing.

EMMERT: Do you feel like some authors do, that now that you’ve created the characters, they sort of have a life of their own, and it’s just your job to translate that to the page?

BECHDEL: I used to feel that way, but to be perfectly honest, they’re vehicles for me more than characters. Vehicles to talk about things I want to talk about. Maybe that will change again, but I feel a little mercenary in that regard, that it’s not more purely fictional. But again that’s the nature of working in this hybrid form, where I talk about real events.

EMMERT: Well, those types of events are going to impact the characters, too, because of the type of strip it is: as you say, a hybrid. Some of that’s going to shape your story, too.

BECHDEL: Right. I like that element of chance.

EMMERT: So the fact that in San Francisco, that they were going to allow gay marriage — and couples getting married — had an impact on things, for example?

BECHDEL: Yeah.

EMMERT: So when you’re creating your strip, do you use thumbnail sketches, like some artists do, or do you have another method that you use for creating it?

BECHDEL: I don’t, strictly speaking, do thumbnails. I write the strip in Illustrator, on my computer, so I can map it all out in terms of the panels and the speech balloons, and I have an idea of how the action is going to break down. I might do a little bit of rough sketching if I’m having trouble visualizing something. But I don’t really do any sketching until I’ve got it pretty much written. Then I begin my complicated, anal, many-layered process of sketching and revising and revising and revising. You know, maybe I should do more drawing earlier in the process. Because I keep writing myself into these incredibly complex panels where I have to draw six characters all interacting in a particular way against a complicated backdrop, doing activities that entail a huge amount of visual research. I guess I suffer from horror vacui, I’m always cramming more and more information into my drawings. But maybe that’s not so terrible. One thing I’m absurdly proud of is a strip I did years ago where in the background, a character was lighting a barbecue using one of those eco-friendly chimneys that enable you not to use lighter fluid. And a friend of mine had just bought one of those chimneys and didn’t know how to use it, but she was able to figure it out from my cartoon. So if all else fails, maybe I can fall back on illustrating how-to manuals.

EMMERT: Is this the same process that you used for Fun Home?

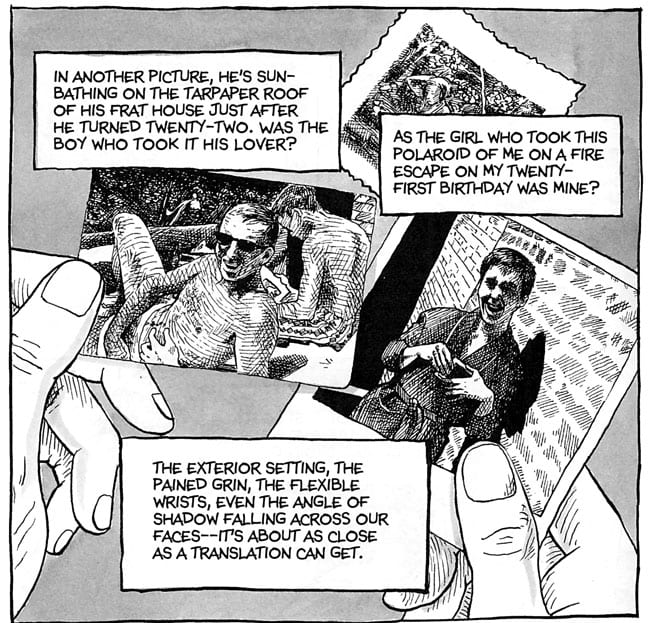

BECHDEL: Yeah, pretty much. I work a lot from reference photos that I take of myself posing as the characters.

EMMERT: I found your little video on YouTube, where you talked about your working method, where you would take reference photographs of yourself to use for your character poses. Can you talk about that, how that process works?

BECHDEL: That’s pretty much it. I mean, you know, digital photography has really changed everything for me. I used to do sketches, I’d look at myself in the mirror, or I’d have friends pose for me if I had a particularly complicated pose to draw. Then eventually I got a Polaroid, which I would use quite sparingly, because it was so expensive. But once digital photography happened, there was no limit to how many of these reference shots I could take.

I feel like I’m perhaps a bit too dependent on them. I wish I could trust my instincts more, trust the drawing that just comes out of my head, but I haven’t gotten there yet. My cartoons are really kind of life drawings. I mean, that’s what they’ve become. They didn’t start out that way, I did draw them out of my head for a long time, with these occasional sketches. But now they’re all based on actual, real live models. [Laughs.] I think that’s a problem. It’s a kind of constrained, tight look sometimes. Sometimes it works well, and sometimes it’s counterproductive.

EMMERT: Do you have things like floor plans for the homes of the various characters in Dykes to Watch Out For in your head or do you have those drawn out so you can sort of figure out references?

BECHDEL: Yeah, I do. I don’t have like a bible, or anything in that sense, but I pretty much know — although I’m not really terribly strict about that, like I’ll have doors open left or right, depending on how I need to use it in that scene, not depending on some Platonic Floor Plan that I’ve got on file.

EMMERT: I’m not one of those fans that looks at stuff like that. “Wait a minute! In that previous strip …” But I’m sure there’re people out there that do that.

BECHDEL: I do pay attention to things like that, with, like, front doors of houses. That needs to be consistent, but inside the house, I don’t care. The layout of Mo and Sydney’s apartment is particularly fluid, but no one’s complained yet.

EMMERT: So can I assume that you do all the work on this? The writing, the penciling, the inking, the lettering — that’s all done by you. You’re not using assistants, like some of the big-time strip artists do?

BECHDEL: No. I don’t know how people do that. I’m strictly an auteur.

EMMERT: Well, Charles Schulz was like that too. You can’t beat Sparky, as far as I’m concerned.

BECHDEL: Yeah, God.

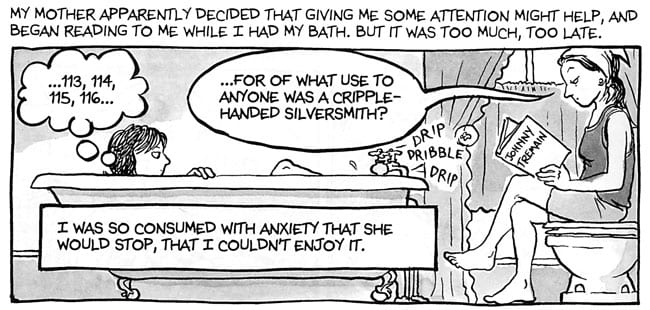

EMMERT: You kind of touched on this a couple of times: one of the themes you had in Fun Home was your obsessive compulsive disorder, and as a person with OCD myself, I can truly relate to it. [Laughter.] Do you think that that has helped you as an artist, or do you think it sometimes gets in the way of your work?

BECHDEL: I think that I’m a very functional obsessive-compulsive — I’m not actively obsessive compulsive now, but I do feel like I’ve harnessed that force in my work in a functional way. So yeah, it very much helps, although, it’s always a balance. I sort of feel like, unless I had a deadline, I would keep inking an individual panel until it was solid black, you know? I don’t know where to stop. That’s always the challenge for me in any drawing: Where do you stop with the detail? Do you stop with the wood grain in the window frame? [Laughs.] Do you stop with titles on the spines of the books on the shelf? Do you include the logo of the publisher on the spine of the book on the shelf? It’s hard for me sometimes to see the forest for the trees.

EMMERT: You said that you frequently will draw, then redraw something before you’re satisfied with it.

BECHDEL: Well, I just go through a lot of successively more refined sketches. I don’t often throw out a final drawing, because I’ve had a chance to get it right.

EMMERT: Right. Well, it was kind of funny, because one of the things I really loved about your work is the detail that you put in. And I know in Fun Home, the fact that there was a Miles Kimball catalog lying on the table just resonated with me. Like you were saying, the titles of the books that the characters in Dykes to Watch Out For are reading, that happen to be on the shelf or something like that are significant.

BECHDEL: It’s very important for me that people be able to read the images in the same kind of gradually unfolding way as they’re reading the text. I don’t like pictures that don’t have information in them. I want pictures that you have to read, that you have to decode, that take time, that you can get lost in. Otherwise what’s the point?

EMMERT: Do you feel that that’s also really just part of creating that environment on that page, trying to make it seem more real as far as the reader goes, or it’s just part of sharing information about that particular scene, or both?

BECHDEL: Well, I feel like if I want people to believe my story, I need to make it as vivid as I can, and that means for me including all these background details and trying to draw emotions accurately. A lot people’s drawing styles leave me cold because they’re not very expressive, you can’t really see what the characters are feeling. So I work hard at that, too.

EMMERT: In Dykes to Watch Out For, you kind of use that black-and-white style of line drawing, but in Fun Home you added that color wash, which I really thought was very effective. Can you talk about that choice, and the difference in the styles?

BECHDEL: That was a whole long complicated thing, because for one thing, I wanted Fun Home to look obviously different from Dykes to Watch Out For. So that was one factor. And the other thing was, if I crosshatched Fun Home to shade it like I do my comic strip, I would still be hunched over my drawing board crosshatching. It’s just so time-consuming. So I knew I needed something that was going to be quicker. For a long time I was trying to do it in Photoshop. I played with all these various possibilities. But I was spending so much time on the computer that it was really unpleasant. I don’t like drawing on the computer, or even just doing shading, which inevitably involved a lot of drawing with a graphic tablet. I hate that, I’m not good at it.

I’ve always loved ink wash, the way that that looks. It’s so sensual, and … I don’t know, there’s something about the contrast between the rich black lines and the gray tone that just gives me a deep visual pleasure. But I couldn’t figure out a way to do that so that the line was solid black, because everything I tried would mean that the line art would need to get screened in the same way that the tone did, and then you lose that solid black. I think of Ben Katchor’s work, he uses ink wash — But it doesn’t have the black in it. It’s fine for his style, but I feel like I need it, you know? Gimme the black! So, I’m sure other people have figured this out, but I kind of work in a vacuum, [laughs] so I made up my own way of how to do this, how to maintain the solid black of the line art, yet incorporate the ink wash. I did them on actual separate pieces of paper, so that I could use my plate-finish Bristol for the line art, because I like a very smooth paper for my drawing nib. But you can’t use ink wash on smooth Bristol board; it won’t absorb . So I did the wash on watercolor paper, and then I combined them as layers in Photoshop. I actually ended up using a smooth, hot-press watercolor paper, though I experimented early on with a rough, textured paper. I liked how that looked, but it sort of obtruded itself too much into the line art. And also I ran into problems scanning it — I’d have tone where I didn’t want any tone. And that was easier to control with a smoother paper.

EMMERT: That was going to be one of my questions to you, as far as your working techniques, of using digital media. So obviously, you are doing that.

BECHDEL: Yeah, yeah. And then I’m using Illustrator for the lettering, I really cheated there. I act like I’m such a purist, but I used a digital font for the graphic novel, which is sort of antithetical to everything I believe in. But again, if I’d done it by hand, I’d still be hunched over the fucking thing, and probably have carpal tunnel to boot.

EMMERT: [Laughs.] So did you create an Alison Bechdel font ?

BECHDEL: Yes. Well, I mean, I had this guy do it. Nate at Blambot. I gave him samples of my actual drawn letterforms. Then he whipped them up in Fontographer. I think he did a really good job. For a while I was using the digital font in my comic strip too, just to save time. But I really don’t like how it looks there. It’s way too regular and uniform. But in Fun Home, I think that uniformity is a plus. My text is so stylistically dense that I didn’t want to make it any more difficult for readers to decipher than it already was. Lynn, these are really great questions.

EMMERT: Oh, thank you.

BECHDEL: I love talking about the technical aspects of the book, and that’s something I miss as the book gets more literary attention. Those people aren’t interested in the line art or the ink wash or the font.

EMMERT: The Comics Journal reader is sort of hard to categorize too. There’s also a lot of cartoonists who read it, and so they’re interested in the technical aspects of other cartoonists’ work.

BECHDEL: Yeah. I love that.

EMMERT: I’m not a cartoonist myself, but because I am a comics fan, I do look at things like that — as to how the work is produced. And then, for me, the impact that it has as a reader. Definitely, that was one of the things that came out when being very familiar with your Dykes to Watch Out For strips, and opening Fun Home, just the very different look of it and how that affected me as a reader. I thought it had a big impact, but it was one of those things that’s subtle. You know what I mean? The difference in the way that it looks; I was wondering too, on how you decided on the color for the wash.

BECHDEL: I don’t even remember. I think that blue range is something a lot of cartoonists have used; I guess I’ve seen it in a couple places. Maybe I’m thinking of Ghost World. It works on a number of levels. It could work literally. Well, in my case, it was more of a greenish color, which worked great in a literal sense, to color grass and foliage. But it was not too jarring to use as a background shade or a skin tone. It didn’t look too weird, whereas orange wouldn’t have worked. I don’t know. Maybe it would. But the green just seems like a very flexible color. And it was sort of a sad color [laughs], sort of a grieving color. That grayish-green has a bleak, elegiac quality to it that I liked.

EMMERT: Have you ever thought about using color in the Dykes to Watch Out For strip?

BECHDEL: Noooo, I hate color. Actually, I sort of balked at the notion of tinting that wash layer at first, because like my dad was a huge color freak, and he really inhibited and intimidated me about color. That was his turf. I always hated painting for that reason. There are too many variables. I think in a way that’s why I became a cartoonist, because I didn’t have to worry about all that shit, just soothing, simple black and white. So it felt like going against my principles to include any color at all in Fun Home. I wanted to prove that you didn’t need color. But then I felt like that was continuing to let my father [laughter] control me. If color worked, why not use it? It did give an emotionality to the drawings that I don’t think it would have if the ink wash was left gray.

EMMERT: Have you ever been approached by anybody to do an animated version of Dykes to Watch Out For?

BECHDEL: Oh, yeah, like every couple of years, somebody has some scheme, and it always falls through or doesn’t go anywhere at all. Lesbians aren’t really that commercially viable [laughs] — in fact I like to think that lesbians are inherently uncommodifiable. Well … at least the lesbians in my comics. I mean, there’s The L Word, but that involves so much capitulation to a mostly straight audience. But there’s no way you could contort my comic strip to work commercially.

EMMERT: Right.

BECHDEL: My characters wouldn’t look very good in revealing lingerie.

EMMERT: [Laughs.] Or designer fashions, or …

BECHDEL: Right. And who would the sponsors be? Home Depot?

EMMERT: Well, I was recently accused of not being in the 21st century, but that’s certainly not an accusation someone could make about you: You’ve got your really great Dykes to Watch Out For website, and your posting on YouTube. So how do you see that translating your strips over to your website? How do you see that digital revolution affecting how cartoonists are working today — and especially your work?

BECHDEL: What is very exciting to me is being able to reach readers directly, and not having to go through a middle person. Much as I have valued the cultural infrastructure that enabled me to do this comic strip in the first place — the newspapers and small presses — it’s kind of amazing to have nothing between me and my audience. [Laughs.] Though of course it is a lot of work, and a lot of money, and so far no one’s come up with a way to make money back online without advertising because everyone expects online content to be free. Anyhow, for me that’s the most exciting aspect of the digital universe. Though it’s also nice to not have to schlep out to make photostats, then Xeroxes, then stuff envelopes to mail my strip to newspapers. I’m not at all interested in drawing on the computer. I don’t like doing it, and in general I don’t find computer-generated images as interesting.

EMMERT: So right now you’re doing all your drawing on boards and then photographing it to place it on your website?

BECHDEL: Scanning it, yeah.

EMMERT: Scanning it, yeah. See, I told you, I’m not in the 21st century. [Laughter.]

BECHDEL: I love technology. I just love fucking around with my computer and figuring things out, and learning new stuff. If I didn’t, I would be in trouble. It’s amazing to me how much has changed since I started doing this. Everything is different. I couldn’t do this without a computer. I couldn’t have done Fun Home without Google image search. I’d still be doing the visual research. But also because things were so readily accessible online, it upped the ante. That’s part of the reason that the book is so detailed — because it could be. I could find exactly what some television show logo from 1960 looked like, with the click of a mouse.

EMMERT: I was thinking about the Brillo box that all the camping stuff is in. It was like, “Wow, how did she get that so right on?”

BECHDEL: Actually, I got the Brillo box from an old family snapshot. But yeah, that’s the idea.

EMMERT: Obviously, the maps and things that are used in the book, which I thought were very effective, because a lot of the book talks about that place and your father being tied to that particular geographical area, and how that impacted his life.

BECHDEL: That particular chapter, the one with all the maps, in a way, that chapter [laughs] is my cartooning manifesto. Because I feel like cartoons function for me very much like maps, in that they take a complex or confusing three-dimensional reality and iron it out into a much more manageable two-dimensional version. [Laughs.]

EMMERT: Yeah. That’s really a great idea, I hadn’t really thought about that, but that’s true.

BECHDEL: Also, maps combine words and images in the way cartoons do.

EMMERT: Well, and I think that’s kind of what you did with your book, is took these very complex ideas — What I was thinking about, an autobiographical book in particular, where you’ve got all of these things that happened to you, and trying to make sense of them, and put them in a coherent way, and I don’t know if I’m making any sense, but — [Laughs.]

BECHDEL: Yeah.

EMMERT: Do you think having the images along with the words was helpful therefore for you to get to that point?

BECHDEL: I couldn’t have gotten there any other way. This is the thing about cartooning for me, is that I really feel like much as I love writing, there are places I can’t go with just words. Language is very rich and flexible, but there are limits to it. That’s where pictures come in. With the combination, it enables me to do things that I think are — I think they’re pretty amazing. I really think the possibilities are amazing. I don’t fully understand them yet, and I don’t have them codified in my head, I’m just working on instinct at this point. But it’s like learning a new kind of syntax, a new way or ordering ideas. I’m just starting to get a grasp on it.

EMMERT: But I have to say, I think your command of the English is amazing. I think Fun Home was one of the first books I’ve read in a very long time where I actually had to have my dictionary handy.

BECHDEL: A lot of people say that.

EMMERT: But I liked that. I thought that was great. Because I think there’re a lot people that think of the graphic novel as sort of a dumb-down. It’s like “well, they couldn’t tell the story in words, so they had to use pictures.” Which kind of goes exactly against what you’re just saying. It’s not that at all; it’s that the pictures are really enhancing what’s going on in the story.

BECHDEL: Right, right. And I wouldn’t even use the word “enhancing.” It’s more symbiotic than that.

EMMERT: Right.

BECHDEL: Saying “enhancing” is still giving primacy to the words. And I don’t think that —

EMMERT: That they’re really both equal and part of what’s creating that artistic work.

BECHDEL: Yeah. I always liked that thing that people would say, you know, cartoonists are people who aren’t really great artists and aren’t really great writers. I think that’s true. [Emmert laughs.] I embrace that: but it fails to account for the fact that writing and drawing together is a completely other thing, a whole different skill. I can be very good at that in a way that’s outside of the frame of reference of just images or just words.

EMMERT: Do you consider yourself an artist who writes stories or a writer who draws? Or are the two so integrated that they can’t be separated as individual skills? Do you feel you’re better at one or the other?

BECHDEL: I do feel I’m stronger at writing than drawing, but that doesn’t mean I see myself as a writer who draws. They’re still inextricably linked for me; I’m just a little better at one aspect of the process than the other.

(Continued)