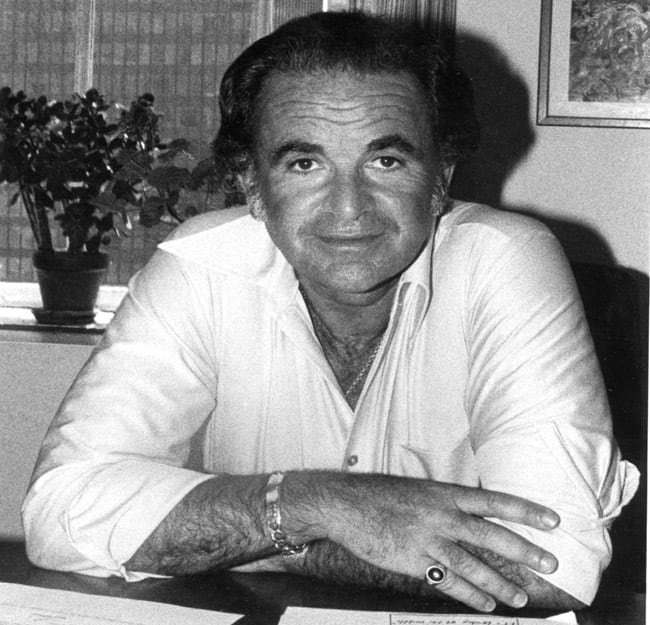

In this 1995 interview for The Comics Journal #177 (May 1995), Al Feldstein takes Steve Ringgenberg behind the scenes of Mad, EC, show biz and more.

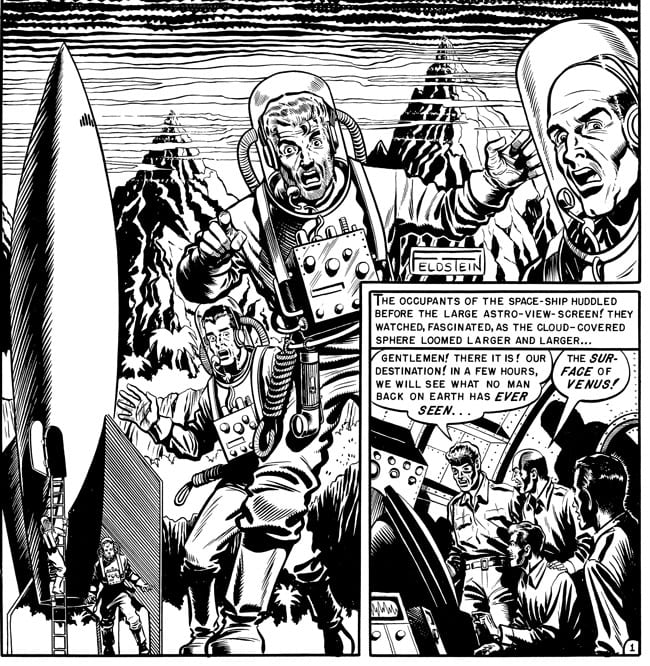

Al Feldstein is one of the true originals of the comics business, a multi-talented writer / editor / artist who has been imitated for 40 years. For all his talent and undisputed creative influence, Feldstein has remained a relatively unknown commodity.

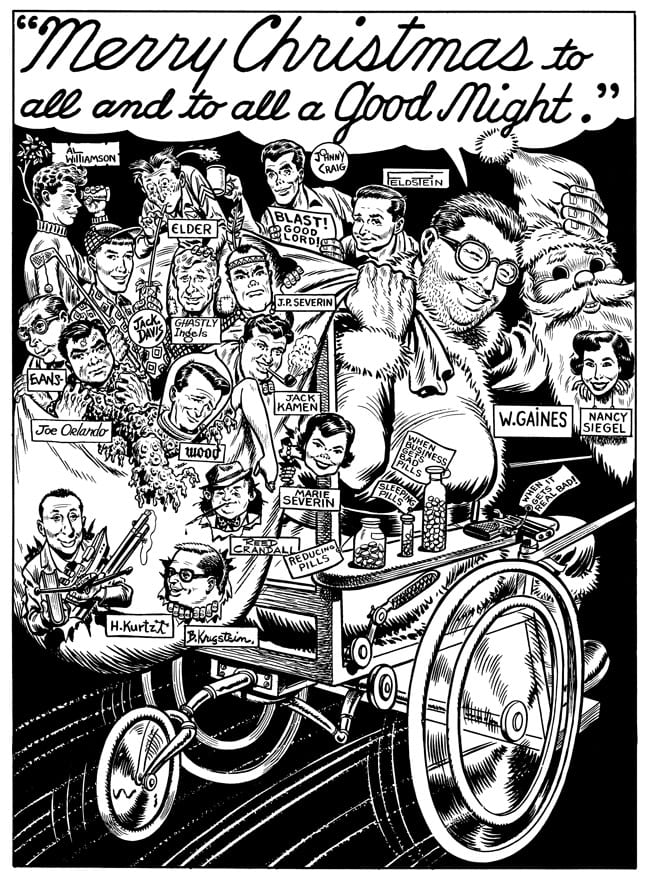

Feldstein’s output is impressive: during the EC era, he produced hundreds of literate, well-written scripts, as well as dozens of covers and hundreds of pages of interior art, all rendered in his stiff, but graphically powerful, style. When EC folded its tents in the mid-’50s, leaving Gaines with Mad magazine as his sole publication, it was Feldstein who kept Mad alive. Feldstein did more than that; he presided over Mad’s transformation into one of the icons of the publishing industry.

Feldstein has been interviewed infrequently. This is one of his longest interviews to date. I found Feldstein to be frank, outspoken and funny. His intimate knowledge of the EC era and Mad history makes him an invaluable historical resource.

— S. C. Ringgenberg

STEVEN RINGGENBERG: When did you become interested in comics?

AL FELDSTEIN: I was going to the High School of Music and Arts, studying to be a fine artist before I made up my mind that I wanted to be an art teacher and I needed money. This is back at the end of the Depression. My folks could hardly afford to give me the money for the subway fare, no less money for dates, so I had to seek ways of earning money. I’d heard that one of the guys in the school was doing comic-book artwork and getting paid very well, like $20 a page, which seemed like a lot of money at the time. I had never read a comic, so I got a couple. I borrowed a couple of comics from somebody and made up a sample portfolio and I went around looking for work. I got a job at an art service, a studio that was working for various publishers.

RINGGENBERG: Was that the Iger studio?

FELDSTEIN: That’s the S.M. Iger studio. It was originally Eisner and Iger, and when I got there they had just broken up and Will Eisner had gone off on his own. Jerry Iger was still servicing various [publishers]. Fiction House and Quality Comics and a few of those. I met some of the really great artists of their time who worked there. I started by erasing pages and running errands and eventually worked up to inking backgrounds and then drawing and inking backgrounds, and eventually worked up to inking figures. It was kind of an assembly line.

RINGGENBERG: How old were you when you started?

FELDSTEIN: I was 15 when I first started to work after school for a few hours at five dollars a week, running the errands and erasing the pages and stuff. Then I worked there during the summers, and eventually I was going to high school. When I graduated from high school, I had a scholarship to the Art Students League and I had made up my mind I wanted to be an art teacher because the teachers at Music and Art lived a pretty good life and I thought, “Wow, gee, $10,000 a year.” You see, I was going to Brooklyn College during the day and going to the Art Students League at night and working in the summers in this art studio, and then along came the threat of the draft. This was during the ’40s, so I enlisted in the Air Force. When I came out of the Air Force, I was going to go back to school to become an art teacher and I took a job in the interim, until the semester started, and I started to make more money than as an art teacher after I left Jerry and started to freelance. I went back to Jerry Iger’s place for a while, and then I started to freelance.

RINGGENBERG: Tell me, was working for Iger pretty good training?

FELDSTEIN: Excellent, because all you did was draw or be exposed to other people’s art.

RINGGENBERG: Who were some of the people you worked around?

FELDSTEIN: Well, let’s see. There was Bob Webb, who was doing Sheena, and there was Reed Crandall.

RINGGENBERG: So you knew Reed Crandall before he worked for EC?

FELDSTEIN: Oh, yes. When Reed showed up to do EC work I was delighted to have him. You know, a lot of the names slip my mind. You’re talking 45 years ago.

RINGGENBERG: A long time.

FELDSTEIN: But there were a lot of good ones there.

RINGGENBEBG: Did you ever work with Matt Baker?

FELDSTEIN: Yes, I worked with Matt Baker. When I came back from the service, Matt was at Jerry’s. I worked with Matt and with Jack Kamen. Matt died but Jack came to work for me at EC.

RINGGENBERG: Had you ever worked with Graham Ingels before he worked for EC?

FELDSTEIN: No. I met Graham when I came to Bill Gaines.

RINGGENBERG: Was Graham already working for Bill?

FELDSTEIN: Yes, he was.

RINGGENBERG: He was doing Westerns, wasn’t he?

FELDSTEIN: That’s right. That’s what I did too when I first ... After the war, when I started to freelance, I ended up packaging teenage books for Fox and I was doing a magazine called Junior and one called Sunny, and then an adaptation of the radio script for a magazine called Corliss Archer. They were teenage books and I was kind of unhappy with Fox. The teenage market really was not that great.

Bill Gaines’ father had been killed in a motorboat accident on Lake Placid, while Bill was going to college. There had been a business manager there named Sol Cohen who was looking for ways to continue the business for the family and he sent word through my letterer that he wanted to talk to me about a teenage book. So I went down there and met Bill and Sol, and Bill drew up a contract. I was going to do a magazine for them called Going Steady With Peggy. Then the sales on the teenage market were showing a weakness. This was something I will get into again, but this was a problem in the industry. There were 600-and-some-odd titles at that time. This is before television and the Senate investigations going on — that kind of hurt the industry. What would happen is that somebody like Simon and Kirby would come up with a romance magazine, or Bob Wood would come up with Crime Does Not Pay for Lev Gleason, and they would start to sell, and everybody would jump on the bandwagon and do a crime magazine or a romance magazine, or a teenage magazine like Archie, you know?

So it was an industry of a few innovators and a lot of followers. Anyway, when I came down there, Sol wanted to follow this teenage trend, and of course the trend was starting to die because then the leaders stay up there, but the imitators start to die because there’s a flood of them. So I said to Bill, “Well, let’s tear up the contract,” which he was very grateful for. I mean, he put me to work writing and drawing whatever I could. I started to do scripts that he had been getting, but I said, “Listen, I can write my own scripts better than this.”

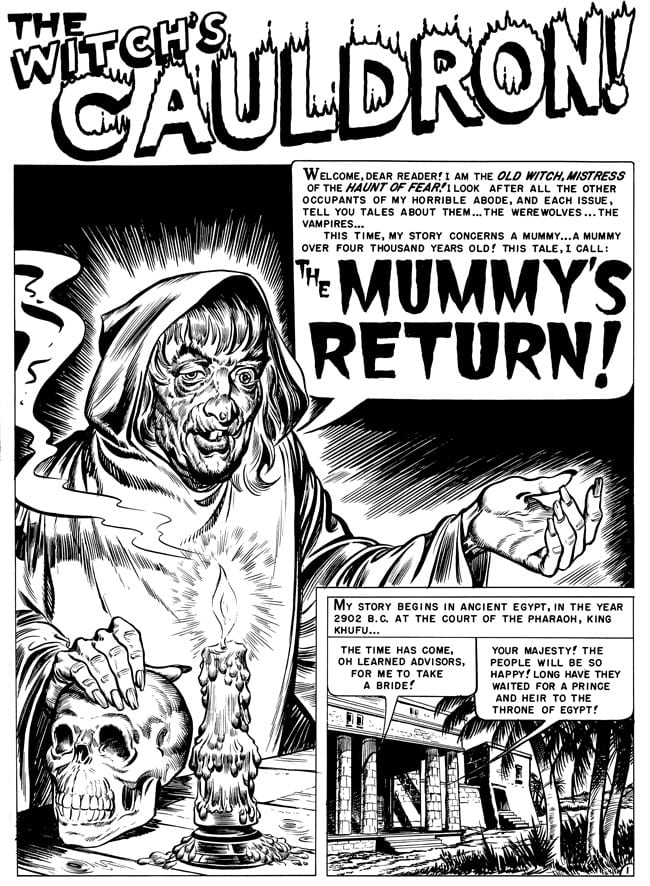

So I was doing Western and crime and I came to him one day and said, “Look Bill, why are we following these idiots and, when the trend dies, getting caught? Why don’t we innovate, and why don’t we have people follow us?” At that time we were very good friends. We used to go to roller derby together and he used to drive me home because we both lived in Brooklyn. We’d chat on the way home and we got to talking about what we liked when we were kids. Bill was a science-fiction and horror fan, and I was a horror-movie fan, and I said, “Why don’t we try horror?” I reminded him about the “Old Witch’s Tale” on Lights Out, Arch Oboler’s stuff on radio.

OLD WITCH STORY

RINGGENBERG: Was “The Witch’s Tale” on the radio your inspiration for EC’s Old Witch?

FELDSTEIN: Yeah, kind of. Yeah, of course. Well actually, what happened was we used the inspiration for the Crypt Keeper. Then Bill wanted more than two, so I did the Vault Keeper, and then I did the Old Witch.

RINGGENBERG: So you were the one who created those characters?

FELDSTEIN: He said, “OK, let’s try it. Let’s put one of your horror stories into Crime Patrol. So I invented what I called “The Crypt of Terror,” or “The Crypt Keeper.” I wrote a story and drew it and then suggested that we try one in War Against Crime. So in War Against Crime we did “The Vault of Horror.” Suddenly the magazine started to show a little sign of increased sales. Even on a basis of check-ups, not on the basis of final sales, he said, “Let’s just change the title.” Now, in those days, magazines were distributed by the U.S. mail through something called Second Class Entry, which was the specific way to ship magazines through the U.S. mail. You had to maintain a Second Class Entry status, and there was a fee to start the status. To avoid a new title and having to pay a new fee, all you’d do is change an old title and hold the same Second Class Entry, so War Against Crime became The Vault of Horror, and Crime Patrol became The Crypt of Terror, for a few issues, and then it became Tales from the Crypt.

He said, “Let’s do a whole magazine.” It was in The Vault of Horror, I think, I first did The Witch’s Cauldron and then eventually did The Haunt of Fear, which was the Witch’s magazine. Now originally I did all three, but then, of course, it was getting to the point where I couldn’t do all this artwork and write the stories too, because Bill had gotten really excited about starting to plot stories when he realized I could write them. He wanted to get into the plotting end of it. He had trouble sleeping because he was constantly dieting and taking Dexedrine and Dexedrine would keep him awake at night. It would also kill his appetite, but it would keep him awake at night, so he’d read. He’d come in in the morning — and this became the modus operandi so to speak — he would come in in the morning with what he called “springboards,” which were little notes about some of the stories or things he had read.

RINGGENBERG: How long were these? Maybe a sentence or two?

FELDSTEIN: [Laughs.] They weren’t even a sentence. Not a sentence. And of course we would try very hard not to steal the story completely, you know, but they would become springboards. We would chat about what to do with that kind of idea, and we would try and do variations, and eventually we started to plot. I started to write four stories a week — well, eventually it was seven titles that I was writing for. On the fifth day we would edit. What would happen is, we would plot it in the morning, and then we’d go out to Patrissy’s and have a big Italian meal. Then I’d go up into the studio, which originally was in the main office, but eventually he got me a studio upstairs so I’d have privacy and not be disturbed. I’d write the story directly onto the illustration board. And I’d start the balloons two lines below the border of the panel, after I’d rule it up and lay it out. Then Jim Roten would letter in the balloons, and that’s how he could read it — because I’d leave a space. But this is all kind of technical.

RINGGENBERG: Why did you choose to use the Leroy lettering?

FELDSTEIN: Bill had been using it. I didn’t particularly care for it. And especially because I was doing a lot of underlining for reading assistance, and the bold lettering would be too big. When Harvey came to work for us, he did Frontline Combat and refused to use Leroy lettering. I think he was right. I think that the EC stuff would have been much better without Leroy lettering but we were stuck with it, and Jim was a friend, and you kind of have loyalty. Bill always had loyalty so we just stayed with it.

RINGGENBERG: OK, so you were doing the horror comics. Then ...

FELDSTEIN: The horror, then we did science fiction. That was the next thing because Bill was a science-fiction fan. Now our science-fiction magazines, Weird Science and Weird Fantasy, when we instituted them, were never as successful as the horror ones. As a matter of fact, the horror ones kind of supported them for a while until they took off. They were never the profit-makers that the horrors were ... but we loved them.

RINGGENBERG: Did they make any money?

FELDSTEIN: Oh yeah. They did not lose money. But they weren’t as big as the horror. We enjoyed them and they caught on after a while because we entered into that period where they were sighting UFOs and things were getting interesting. Science fiction was getting a little more popular, so we were doing well with those two. Then we invented two crime-type magazines, but they weren’t crime in the Crime Does Not Pay sense; they were snap-ending, poetic justice, O. Henry-type stories in the crime venue. They were Crime SuspenStories and Shock SuspenStories.

RINGGENBERG: The material in those was pretty hard-edged, I think, because it was more realistic than the horror comics.

FELDSTEIN: Yeah, well, as a matter of fact that’s where we did a lot of preachy stuff, a lot of, you know — we hit the drug area, racial area, things like that. That was my love because I was an ultra-liberal when I was young, and a socially conscious person, having grown up in the Depression and seeing my parents lose their home, etc., etc. So this was a good outlet for some of the stuff that I wanted to do, that had some social commentary, and which was a predecessor of the social commentary in Mad.

In the meantime, a young man walked into my office, and I was at my peak at that time. I just couldn’t write any more, and I was not even doing as much artwork. I was doing covers and occasional lead stories. So Bill was paying me an editorial fee rather than an art fee, which maintained my income. So Johnny Craig took over Vault of Horror. Well, he took over the lead story anyway, “The Vault Keeper,” and Graham took over “The Old Witch.” But we would write the rest of the stories. Well, Graham didn’t write his stories. We wrote all of Graham’s for him, but Johnny wrote his own.

RINGGENBERG: Didn’t Craig eventually take over editing Vault of Horror?

FELDSTEIN: Vault of Horror? Kind of, yeah. He kind of edited it with Bill. But he only wrote the lead story. Bill and I would write the rest of the stories in it. So it was like he was appointed the editor because he did the lead story.

WRITER’S BLOCK

RINGGENBERG: Did you ever have days when you were blocked and you couldn’t actually write the script you needed that day?

FELDSTEIN: [Laughs.] Well, it’s funny you should ask. Yes. Once we had a blockage, and I had been fishing that weekend, so I told Bill that I’d write a story because I had gotten a feeling for a story while I was fishing. I had a Surfcaster in Long Island where I lived, so I did the story where the the guy is fishing and he picks up the sandwich and gets dragged into the water. You remember that one?

RINGGENBERG: Oh, sure.

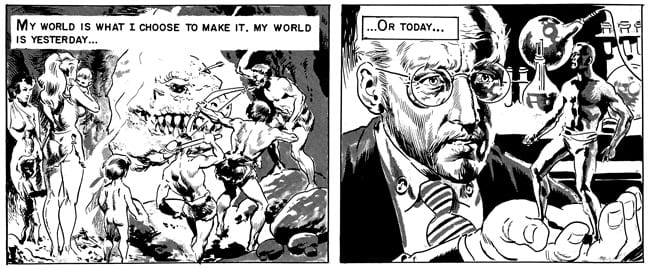

FELDSTEIN: Well, that was a block. The other one that I remember clearly as being a blocked day was when he said, “Oh, Jesus, I can’t do anything today. Go write something.” So I went upstairs and did “My World,” which was a science-fiction pièce de résistance, I think, that Wally [Wood] drew so well, and it became a pretty famous story. But it was really mine because I wrote it.

RINGGENBERG: You say that was the result of a blockage, but that story really is a classic. It’s been reprinted so many times.

FELDSTEIN: Yeah, well, when I said blockage, I meant an idea block in terms of plot and not blockage in terms of my writing. I was prolific and I loved to write. In fact I think I overwrote in some instances. But yeah, that has become a classic. The interesting thing is that in all of these stories I wrote I never got actual credit for writing, although little by little the fans have discovered that [I wrote] all of those early stories. I didn’t start to work with writers until later on. And still, they were completely rewritten.

RINGGENBERG: The story of how EC came to work with Ray Bradbury has been gone over many times.

FELDSTEIN: Whatever story it is, it’s true. Bill and I adapted an idea that we thought was different, and it turned out that it was pretty close to Mr. Bradbury’s story, and I didn’t know anything about this. See, I was not the springboard guy, Bill was. He wrote to us and said, “Hey you guys, you stole my story.” And Bill says, “No we didn’t. But here’s $25 and can we steal some more?” So he allowed us to, because he liked what we did. He allowed us to adapt his stories, and that’s where I really got kind of interested in writing. Because I absolutely admired and adored Ray Bradbury’s writing, and I tried to imitate it in some of the writing I did for the science fiction and later on for the rest of the stuff.

RINGGENBERG: Were there any other science-fiction or horror writers whose stories you paid to adapt, like Katherine Kurtz?

FELDSTEIN: No. I think we adapted [Otto] Binder’s, there was something called “I, Robot”...

RINGGENBERG: The Adam Link stories.

FELDSTEIN: Adam Link. I think we adapted a few of those. But nothing as extensive as Ray Bradbury. We only had four stories an issue and to do one adaptation — we’d still want to do originals. Bill and I enjoyed plotting them.

RINGGENBERG: I remember seeing one credited for the original inspiration to Guy de Maupassant. I think it was the one about the emerald necklace.

FELDSTEIN: Oh yeah, yeah. We adapted stories with switch endings like O. Henry’s short stories, like the hairbrush and the watch fob — you know that one?

RINGGENBERG: Oh sure.

FELDSTEIN: We did many switches on that kind of thing. We also got into some formulaic plots too, like what we called “The Preachies,” which were poetic justice kind of things. You step on a cockroach and a cockroach steps on you kind of thing.

RINGGENBERG: It seems like you gave a lot of those to Graham Ingels — the-worm-turns, little-guy-gets-his-revenge stories.

FELDSTEIN: In the horror trend, yeah. But we also did them in science fiction. We had interesting science-fiction plots where space explorers would end up in zoos, things like that, plotting an alien civilization. We just tried everything. We really had a wonderful time doing all that stuff. And of course, in the mid-’50s, ’53 or ’54, Estes Kefauver wanted to be president and he started a Senate investigation into organized crime in America. As part of this investigation committee, there was a subcommittee on juvenile delinquency which was getting to be a problem for the young parents that had come back from the war and were used to having the Army tell them what to do.

They wanted people to tell them how to bring up their kids, which is why Spock did so well with his book. So they all wanted a little help in this thing, they wanted some sort of guidance. Of course it went overboard, like everything else goes overboard, and the Senate Subcommittee investigating juvenile delinquency took on the comics because they had this self-appointed expert named Wertham. Of course this was like the end of our Golden Era, as it was, because we suddenly became these terrible people who were doing these awful things. All we were doing was entertaining; I wrote a horror story that was all tongue in cheek. The Crypt-Keeper made terrible puns, horror puns, about the plot or whatever, much like it is now being adapted on HBO.

END OF AN ERA

RINGGENBERG: Bill Gaines’ reaction to the whole Senate hearing thing has been well documented. How did you feel at the time, Al? Were you scared?

FELDSTEIN: Well, I was concerned in terms of my bread and butter. I had a wife and babies, a mortgage, and yes, I was scared. I appeared in a closed session with them and they never called me to appear in public — I guess because I explained to them that I was acting as a professional and writing what I thought would sell, that we had no intention of destroying American youth, we weren’t forcing people to buy the magazine and the whole thing really was off to a lot of undercurrents. There were a lot of things I’ve heard since and have come to understand since. For example: There was a whole movement to try and enter into the freedom of the press area, in terms of censorship, and that helped to champion this particular cause. Also, the industry was annoyed as hell at us because we were starting to take away some of their sales from their funny little animals and their kids’ stuff.

We were writing rather adult material and the kids loved the horror and the science fiction, and we were upstarts. They would have liked to have put us out of business, which they eventually did with the self-censorship group, the Comics Code Authority, which gave me such a hard time, even with my New Direction stuff, that I eventually ... It was just awful. Eventually, we had to go out of business. Bill Gaines became enamored with a gentleman named Lyle Stuart, who was running a kind of a muckraking newspaper called The Independent. Old Mr. Lee, who was our business manager, took care of the books and managed the office, and was going to retire. He invited Lyle to become the business manager of the office. So Bill and I were no longer as close as we were.

RINGGENBERG: How did you feel about Stuart? I mean personally?

FELDSTEIN: Well, he was an interesting guy. I had admiration for him for protesting the bounds of censorship in those days because I really believed in freedom of the press. I believed that anybody should be able to read what they wanted to read and probably should be able to say what they wanted to say, and I always have stuck to that, even through the Mad years. But the point was, Lyle had antagonized Walter Winchell, who was quite a powerhouse in those days, in his Independent newspaper with exposés, etc.

I wasn’t too familiar with what he did, but I found out that Walter was after him and that’s one of the reasons we might have run into trouble with some of our [comics], like Panic, in Hartford, when they banned Panic because we did a takeoff on the “Night Before Christmas” poem. I mean, it was getting ridiculous! But Walter Winchell had some friends in various places in the New York City Police Department. We got raided for a Mickey Spillane takeoff. Panic got a couple of blasts. Look, I’m not sure if this is true, and it’s something that I will not attest to, but it was discussed with me by a gentleman who interviewed me like the way you’re interviewing me in terms of writing about that item, and about Walter Winchell and his influence.

RINGGENBERG: That’s interesting. Tell me, was Panic a success? Did it sell well?

FELDSTEIN: It sold. I didn’t sell like Mad, but it sold. It was at least my training ground for taking over Mad when Harvey left. I was doing the New Direction magazines and Panic and having a hell of a time getting all this stuff through the censorship judge — what the hell was his name? Murphy was the czar at that time. They were really tough on us. I think they were too tough on us because they wanted to nail the publisher. There’s that famous story about the science-fiction story we liked to rerun, about the orange robots and the blue robots and this space galaxy investigator comes to see whether this planet is ready for admission into the galactic empire, and he decides that they’re not ready because there’s prejudice.

RINGGENBERG: Right. “Judgment Day.” Another classic.

FELDSTEIN: Right. Yeah, and the last scene was that he took off his helmet and he was black, which was a socko demonstration that yes, racial equality now existed in the universe. And Murphy wanted to change it. He couldn’t be black. I mean, we were really disgusted. It was arbitrary. It was unfounded. [He] had no reason to be on us about this. But that’s what we’d been going through. After we had had so much fun doing all this stuff, it was really kind of a drag. And the other [thing] of course: What happened was that Leader News Company, who was distributing our stuff and imitating our stuff, putting out their own horror comics and science-fiction comics, when the debacle happened, they got caught and not only started to lose money on their publications, but they were getting into trouble with the distributor and we were in trouble with [them] because financially we were dependent on them for our advances and for our settlements of our sales.

So when they went bankrupt, we really were in big trouble, and that’s when Harvey ... Well, we had taken Mad out of that mess because we knew Mad could not get through the censorship code and we turned it into this 25¢ larger magazine, and had luckily gotten a different distributor for it. Harvey saw the handwriting on the wall that EC was going to go down the drain, and he had been contacted by or he contacted — I don’t know which — Hugh Hefner, to do a kind of slick version of Mad. So he came to Bill and demanded 51 percent control of the magazine, and Bill told him to go to hell. Meantime, I was out looking for a job just because we had dropped everything except Mad.

RINGGENBERG: What did you do after all the titles except Mad folded?

FELDSTEIN: It was about a two-and-a-half-month period. I’m not sure exactly how long it was because I’ve repressed it. But I wrote a couple of scripts for Stan Lee and I was looking for a job with a publisher starting a new line of comics and I had lots of ideas and I had dummies and everything I had made up. I had just made a contact and the guy was extremely interested, and we were going to have an agreement conference. I got off the Long Island railroad after being reassured that I had a place there and that he was very interested. I got off the train and there was Bill waiting for me in Merrick, Long Island. He said. “Harvey quit. What do we do? I want you to come back to work for me.”

I said, “What do you mean, what do you do? You do Mad is what you do.”

He said, “Well, do you think you can do it?”

I said, “You’re damn right I can do it. And I’ll do it the way I’ve always dreamed of doing it.” Now, you have to go back, I want to go back for a minute. Harvey and Johnny and Bill and I, at work, we were kind of a family, and we had a lot of bull sessions together. We would brainstorm together. I used to walk Harvey home from the office to the subway station and chat with him. When he first started Mad, he was doing nothing but satires of the kind of stories we were doing in the other magazines, which is what originally Mad started out to do — to satirize our stories, the science-fiction and crime stories.

If you look at issues #1 through #3 or so, that’s what they were. I said, “Why don’t you satirize other things besides the comics industry? Why don’t you satirize America? Why don’t you satirize movies? Why don’t you satirize comic strips? The radio programs and stuff like that?” So he started to do that. The Lone Ranger was one, then “Superduperman” kind of helped Mad take off. Then he started to do King Kong and the rest of them, and that was the pattern. Then of course when Mad was turned into a slick, he was pretty well set on where he was going — but it all came out of a cooperative input on the part of all of us, especially me. So I told Bill, “You know, Bill, I...” and I showed him a dummy of a magazine I had been carrying around that I had wanted to do. It was a little more sophisticated than Mad, and was going to be a showcase of all of these new comedians who were showing up, like Nichols and May, and Shelly Berman and, if I could keep him clean, Lenny Bruce.

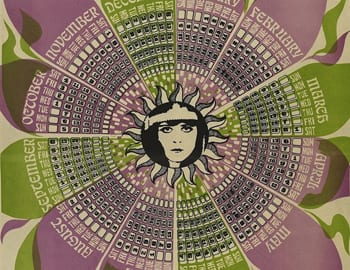

I wanted to do this magazine where they would have a free rein in it. That’s the first I did when I took over Mad, aside from adopting a mascot, because Playboy had the rabbit, and Esquire had the old lecher, Mr. Esky, with the high hat and bug eyes. I said, “Let’s take this little thing that Harvey was fooling around with, and actually make it into something that we can use in our cover all the time instead of just in the border.” So I hired a portrait artist to paint this definitive portrait, and I gave him the name, Alfred E. Neuman. Alfred E. Neuman was a name that had been kicking around the office, and I had used it as a pseudonym in the Picto-Fiction magazines. Whenever there was a second story that I had written I gave Alfred E. Neuman as the author because I didn’t want it to seem that I wrote half the book because there were only four stories in it. So there would be a story with my byline, and there would be a story with Alfred E. Neuman’s. You can find those in those old Picto-Fiction magazines. So, I kind of liked that name, and when I started to use Alfred as our cover logo mascot and started to define the philosophy of the magazine, I had him named Alfred E. Neuman, and I had Norman Mingo paint the portrait, and that’s where we started from.

Finally I took over Mad and as an experiment I went to Ernie Kovacs, and Bob and Ray and I said, “You know, I’d like to adapt some of your stuff into this magazine, make it kind of a showcase for you.” You can see that the early issues had lots of Jean Shepherd, Danny Kaye, and Ernie, of course, and that’s how I developed two wonderful talents [Bob and Ray] that became mainstays of the magazine. Tom Koch was writing for Bob and Ray and I had picked up a couple of his scripts and was adapting them for Mad and I asked him if he’d like to write for us too, and that’s how he got started with us.

Then I needed some artwork, or artists, because Harvey had taken everybody when he went to Hefner, and some kid walked into the office and he had been doing kind of hillbilly stuff and some work for DC. His name was Mort Drucker. I said to him, “Mort, did you ever do a caricature?” He said no. “Well, I’ve got this script here of Bob and Ray and I need to have somebody who can make it look like Bob and Ray are doing the characters. Here are two 8-by-10s, one for Bob, and one for Ray,” He brought back these caricatures of Bob and Ray, which we published on the top of the first story of the adaptation of the Bob and Ray stuff, which was “Mr. Science.” Which was the takeoff of Mr. Wizard, and that’s how Mort Drucker got started in caricature, and I think now he’s probably one of the best caricaturists in the country.

A CULTURAL FORCE

RINGGENBERG: It’s interesting how many of the EC alumni, like Jack Davis, Drucker and Frank Frazetta, have gone on to be fabulously successful.

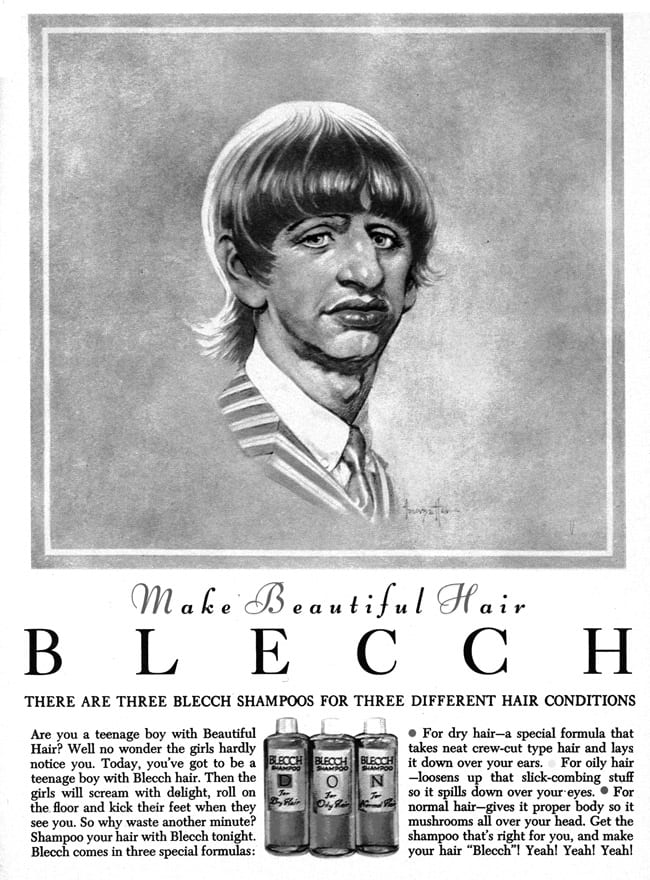

FELDSTEIN: Well, Frank had been moderately successful in the comic business and we were lucky to get him for the time that we did, and he did that wonderful painting for me of Ringo Starr for the Breck ad that we ran.

RINGGENBERG: He only did a couple of things for Mad.

FELDSTEIN: We ran into this problem that his wife had decided she would not permit anybody to buy his artwork outright. Bill was not having any part of it, so we just couldn’t use him. I felt it was a legitimate claim and I had always been empathic to artists, but I was always empathic to writers too, because the artists weren’t worth a damn without good writing. As a matter of fact, it was through my efforts that eventually — and when I started in the business I used to get seven dollars for a page of script and $21 a page for of art, or something like that, three times the amount — and very quickly on, when I started to use script writers and especially when I took over Mad, I convinced Bill that the writing was extremely important and that these artists were great, but we needed the words to help the pictures. Because just pictures alone isn’t going to do it. We eventually got to the point where we were paying equal rates per page, for art and script.

When we were developing the writers for Mad, a lot of them were found through the mail by both myself and Jerry DeFuccio and Nick Meglin, who had come to work for me. Writers like Larry Siegel and Stan Hart and Arnie Kogen, I had pushed to pay them for each page of Mad as much as the artists got, because without it, we didn’t have a magazine. And that, of course, I assume, continued since I’ve left.

RINGGENBERG: I think Mad pays some of the highest rates for script in the business.

FELDSTEIN: Well, I can’t tell you what’s gone on since 1984, when I left, but we were paying very well. The only thing is, guys like Hart and Siegel and Kogen went to California and got jobs with Carol Burnett and Bob Newhart and people like that, and they were getting paid a lot of money — yet they were kind enough to continue to write for me out of a kind of loyalty and an appreciation for the fact that I gave them their start. When they went west to the television city, they would tell me that their best credits were the credits that they had written for Mad, and that that had got them entry into many, many jobs. So that was kind of gratifying.

RINGGENBERG: Was that when you started realizing that Mad was becoming a cultural force to be reckoned with?

FELDSTEIN: Yeah. Well, it became a culmination of my dream as an editor/writer/artist that I was able to have a product that was as effective and as far-reaching as Mad became. As an aside, when I first took over Mad, it was doing fairly well, and I’m talking about through the mid-’50s. I took over in spring of ’55 or fall of ’55. I took over some of Harvey’s material and then started to develop some of my own as I finished that inventory.

RINGGENBERG: How much material did Harvey leave you with when he left?

FELDSTEIN: I closed up an issue that he had done, and then I had about half an issue of material he had bought for the next issue. I disposed of that in the magazine.

RINGGENBERG: Were you in the position of having to really scramble to get that next issue out?

FELDSTEIN: It was tough, yeah. Jerry and I wrote the whole thing ourselves because we didn’t have any writers and I think our first writer who walked in was Frank Jacobs. I welcomed him with open arms and started buying material. I tell you, it was like I was under a charm. I was really extremely lucky when I took over this project of trying to continue Mad and make it work, because out of the woodwork came all of these wonderful associates. Bob Clarke walked in looking for work. I told you about Mort Drucker, but that was a little later on. Early on, Jack Davis came back from Harvey and started to work for me.

A little later on Al Jaffee came back from Harvey and started to work for me when Harvey got into trouble. The writers started to appear through the mail or directly. Don Martin walked in one day very early on, this kid from I-don’t-know-where, Florida, Jersey, somewhere. But he came in with his little bent feet and funny cartoons. I immediately said, “Let’s pick up a little page for you.” I think originally it was an advice page, then later on he started to do just these crazy, crazy continuities, single-pages, cartoons.

RINGGENBERG: When was it that Don Martin joined the staff?

FELDSTEIN: Very early on. It was probably ’56 or ’57. I can’t remember exactly because it was chaotic. It was one of these periods in my life when things were just flowing into place and working right, and we got a new distributor and the magazine started to sell better ... And then of course there was this interesting aside, which made me wealthy. [Laughs.] Well, not wealthy, but maybe very highly paid. Bill and his mother and sister owned the magazine and they had money in their own right, and in those days, in the late ’50s, there was a graduated income tax. It went from God knows what, to maybe 90, 89 percent, something like that, on an ordinary income it was really not like today where there’s a 32-, 38-percent top or whatever it is, and Mad had started to do well.

I had gotten it up to a circulation about 450,000 or so, 475, and the IRS said, “Hey, you got a surplus of a million dollars, and either you invest it in another magazine, or do something, or you’ll have to declare it as a dividend, because you can’t just keep this after-tax, corporate surplus.” So they got a little panicky, and their accountant came up with the idea of finding a company that had a tax loss where they could shelter this surplus. They found a textile machinery manufacturer called Premiere Corporation, which had this write-off from, I don’t know, machinery that didn’t sell, or machinery that was returned to them or whatever. So Mad was sold early on to Premiere Corporation, for I think it was about $5 million. It was a million dollars down, which was the surplus. So they took over the company and gave Bill the million dollars surplus, and he paid capital gains on it, he and his mother and sister, which at that time was 33 percent. So that’s a lot better than 85 percent, and that’s why they did it.

LEAVING MAD

RINGGENBERG: You had said while the tape was off that you felt when Bill sold the magazine that it was kind of a slap at you.

FELDSTEIN: No, no. It was a slap at the magazine. Well actually, see, I don’t think Bill ever really understood Mad. I mean, he understood the horror and the science fiction. He participated completely on the crime stuff. He was part of the creative effort and he felt part of it. But Mad was something he had no feeling for. He enjoyed it as a fan, but I had full rein. When the magazine went to press, he would get the dummy, the mechanicals, and he would read it for the first time. He had no idea what was going to be in it or anything like that. He rarely instituted any kind of censorship except where I might have over-stepped legal bounds, or he thought he might get sued for copyright or something like that. But aside from that, he never said a word.

We were at different poles politically, and some of the things he didn’t agree with politically, but he still let it go because it was a cultural, social-comment magazine and he knew it had to cover all bases. Anyway, he sold the magazine and I was furious because I had wanted a piece of it. I said, “I didn’t want what Harvey wanted, but you should have given me a piece of it before you sold it so I could be in on the gravy too.”

He said, “Well, I’ll tell you what I’ll do. Al, I’ll give you a work contract with a percentage of the magazine. And because it’s going into the hands of a corporate entity, we’ll keep their expenses out of it by giving you a percentage of the gross sales of Mad.” So he gave me a work contract with a percentage of the gross, which meant at the time, about a $25-30,000 raise from what I was making. Which was kind of nice, you know? I mean, we’re talking now about the late ’50s.

RINGGENBERG: You must have been thrilled.

FELDSTEIN: Well, I was at least a little pacified, because I said, “OK.” I said to myself, “Well, now it’s up to me to do something with this magazine.” Well, it went from 435,000, to 2,800,000. That was the highest sales — the Poseidon Adventure issue. It went from nothing to 200 paperbacks. It went from nothing to 11 foreign editions. [Laughs.] This all after that contract. So Bill ended up going around bragging that I was the highest-paid editor in the world which wasn’t exactly true because there were higher-paid editors like Henry Luce and Hugh Hefner. But I was doing very well at the time that Mad was acquired, through a series of acquisitions.

FELDSTEIN: Well, I was at least a little pacified, because I said, “OK.” I said to myself, “Well, now it’s up to me to do something with this magazine.” Well, it went from 435,000, to 2,800,000. That was the highest sales — the Poseidon Adventure issue. It went from nothing to 200 paperbacks. It went from nothing to 11 foreign editions. [Laughs.] This all after that contract. So Bill ended up going around bragging that I was the highest-paid editor in the world which wasn’t exactly true because there were higher-paid editors like Henry Luce and Hugh Hefner. But I was doing very well at the time that Mad was acquired, through a series of acquisitions.

First, Premiere sold it to Lionel. Lionel sold it to Independent News/National Comics, DC, and then everything went to Warner, which was Steve Ross’ burgeoning entertainment conglomerate. So we ended up there. Of course Steve had looked at the Superman material and the distribution of the magazines because he had bought the magazine-publishing companies, so we entered into kind of powerful arenas, and that’s how the magazine, our magazine, Mad, became successful — because we had good distribution and everything else.

RINGGENBERG: Whenever the magazine turned over, did it have any effect on the day-to-day running of the magazine?

FELDSTEIN: No. Absolutely not. Nobody came near us, not even the Warner Communications Group. There was a mystique that Bill had built up about him and his staff that we don’t get touched. Even when they bought the building in the Rockefeller Center complex, when they bought their own building and brought all of their conglomerates into that building — the publishing and the books and the paperbacks, and the magazines and the records and everything like that — we refused to move.

Bill refused to move in. He wanted to stay at 485 Madison Avenue, Mad Avenue, and not have anything to do with them. Because he felt they would start sticking their noses in, that we would be disturbed, that our artists and writers would become enamored with what was going on. So we maintained our independence. They’re still there over on Madison Avenue, although I think when the lease runs out they’ll probably end up, now that Bill is gone, in the Warner Communications [building]. It’s Time-Warner now.

RINGGENBERG: Do you think Bill’s refusal to move also stemmed from his being a creature of habit, not liking change?

FELDSTEIN: Oh, absolutely. And that of course was part of the reason why I retired. I saw the handwriting on the wall. I mean, we’d had a good run, but we had, I felt, to expand the scope of the magazine to include other things, especially other media that were becoming prominent, such as tape, movies, television. We should be in that, and it grieved me that shows like That Was The Week That Was and Saturday Night Live were coming on the air and we weren’t doing anything. And that even our competitor, National Lampoon, was doing movies like that frat movie — what the hell was the name of it, where they threw the food around? Well, anyway...

RINGGENBERG: Had you stayed with Mad beyond ’84, what would you have liked to do with the magazine?

FELDSTEIN: Well, the reason why I didn’t stay was because I couldn’t do anything with the magazine as long as Bill was in charge. Bill refused to take advertising. I felt at that time we had passed from something we were very proud of, the fact that we had not taken advertising and therefore would not be subject to the pressures of advertising, which was a kind of a paranoia that existed in the ’50s and ’60s, and that now teenagers were becoming acquisitors, they were buying things. I thought we could have an advertising area in Mad that would not affect editorial in any way, that would assist in making the package a little more attractive, and that we could even do humor advertising and have our own advertising agency.

Anybody that wanted to advertise in Mad would have to go through the Mad advertising agency and do a humorous ad. But he wasn’t having any part of it. Because Bill basically was a comic-book publisher, and also he did not own the magazine, so he didn’t want to have a big, sprawling organization with a lot of headaches when he didn’t need it. He just wanted to have a place to come and work, and go out and eat. Anyway, we started to have some conflicts, Bill and I. I had all kinds of ideas. I wanted to do a tape, a VHS version of Mad, if I could. I wanted to investigate the packaging of a monthly or bimonthly or a quarterly tape and have it at a price that was really reasonable because tape in and of itself, the cassette, doesn’t cost that much. We probably could have put out something for $4.95 as a quarterly where we would give them an hour show of the magazine, uncensored.

I wanted to do traveling college players that would go from college to college with the Mad Show and have a writer traveling with them so they could update the material as it happened, you know? Like when we had this kind of blah invasion of Haiti. We could have done something on that, you know? I had all kinds of ideas, but Bill was having no part of it. So my last contract was for, instead of five years, I only took three years because I figured I was going to quit. In the last year of my contract, my third year of my three-year contract, my wife developed lung cancer and I left anyway. But I would have left whether she had had lung cancer or not, but Bill thought I had left because of my wife’s condition, and that wasn’t really true. I saw the handwriting on the wall. When I left Mad. it had reduced in sales from 2.8 million to about 1.75 million. And as of now, about 5-700,000. It’s really sad, you know. I pounded on doors ... I didn’t want to hurt Bill in any way, but I had certain friends over at Warner Communications and I would tell them what was happening and what should be happening, but they couldn’t touch him. He was the guy in charge and he had the mystique that without him it would fall apart. Well, he’s not there now, and it’s going on fine.

RINGGENBERG: After you left the magazine did you continue to have a decent relationship with Bill?

FELDSTEIN: Oh yeah. Well, it was cordial. It wasn’t as close as it had been before Lyle Stuart. I mean, that’s when we were really close. It had never been as really close as over the Mad period, because I was making money, you know. He wasn’t happy about that and he was terrorized that I had so much power. Not that I wielded this power, you know, but he was dependent on me to continue developing the magazine. But there came a point where I just felt we weren’t going to go anywhere and I had proved to be right because the magazine has deteriorated in sales. It could have been just natural attrition as well as anything else, but I felt that there was enough scope that we could have offset it with other kinds of things.

SHOW BIZ

RINGGENBERG: When you were doing Psychoanalysis I had heard that there was a psychiatrist TV show that you worked on.

FELDSTEIN: Yes. I was approached by the Steve Allen group, and I went down to talk to them about it. Steve preceded Jack Paar at the Tonight Show, who preceded Carson, who preceded Jay Leno. Steve Allen was the nighttime TV wonder boy at the time and he discovered Steve Lawrence and Edie Gorme and he had, oh God, some of the comedy people he had went on to do wonderful things in other programs. He was in analysis at the time and he called me up and said, “I read this, somebody showed me this thing. Come on down. I want to talk to you.” So I came down to his studio and of course I was very impressed. I mean, here was this big TV star, and all the people around him and everything. He said he wanted to adapt this to TV, he thought it would be great, and he thought that he would give a kind of a pilot show based on something like this, on his whatever it was, two hours at the time, or an hour-and-a-half to two hours every once in a while.

I said, “Gee, I’d love to participate.” So he put me together with a writer named Howard Rodman, who was a fine TV writer of his time on a par with Rod Serling and the rest. We’re talking now the ’50s, you know? I think he put two on. We wrote two together, and I wrote one by myself, but that never got on. And NBC said, “Come on, you’re a nighttime variety show. What are you getting serious for?” Of course then the thing was redeveloped by another producer, and they called it The Eleventh Hour, which was on for a while. Yes, there was a TV show, and yes, it was inspired by Psychoanalysis, which Bill and I had come up with as part of our “New Direction” after we were censored out of the horror because we had both been going. I was in analysis and he was in analysis. It was the ’50s thing to do when you had a little money and you had problems.

RINGGENBERG: How long did the Eleventh Hour show run?

FELDSTEIN: I have absolutely no idea. I know it ran for at least a season, maybe two. [It ran for two seasons.]

RINGGENBERG: Did you and Bill have any involvement with it?

FELDSTEIN: No. We had absolutely no involvement in it. And the Steve Allen thing, which was called The Psychiatrist, never got anywhere. He did two pilot episodes on his own Tonight Show or The Steve Allen Show, which was on at 11:30, after the news in New York. I don’t know how it ran for the country. He would have this show, which is now like Jay Leno and David Letterman, but it preceded Jack Paar and Johnny Carson. It was that show that lead into those guys. He did it on that show. He did two dramatic sequences of The Psychiatrist.

RINGGENBERG: Were they just the psychiatrist with one patient?

FELDSTEIN: Yes, it was a little drama, it was a kind of an instant analysis thing, you know?

RINGGENBERG: Yeah. Solve all your problems in 15 minutes.

FELDSTEIN: Right, with a little dramatics, and a person comes to the psychiatrist with a problem and they talk about it and there’s some little flashbacks and some searches into what he remembers or what he dreams, and then they act that out, and all of a sudden, the revelation comes, you know? It was fun. What I really enjoyed about it was becoming a friend of Steve’s and we kept in touch for many years after that.

RINGGENBERG: I assume being the ’50s, that the Psychiatrist segments were done live on the show?

FELDSTEIN: Oh, yeah. The whole show was live. The skits were live. That was the wonder of television in those days. Playhouse 90 was live, all of the dramatic shows were live. And because they didn’t tape — or actually it was wire back then, I don’t even think they had plastic tape — the electronics were not that good, so when you see some of those old ’50s shows, the only way they were able to record them was filming it right off of the screen. Some of the very old shows that you see replayed, not I Love Lucy, but like the old Jackie Gleason Honeymooners, the very early ones, those are called kinescopes.

Kinescope was actually photographing it as it came on the screen. There were certain adjustments that had to be made because a movie Camera! takes a 30th of a second. And the sweep on the screen was out of sync with it, so you’d get a moving bar running up it. So they had to re-sync, and shoot them differently. Your Show of Shows, Sid Caesar, Imogene Coca, and those guys, that was all live. It was a great time because it was spontaneous and things happened: Scenery fell down, extras walked behind sets and screwed things up ... And there was no such thing as canned laughter. A comedian either got a laugh or he didn’t. Milton Berle was live.

RINGGENBERG: I know that back in the ’60s you put on The Mad Show. What was the genesis of that?

FELDSTEIN: The daughter of Richard Rodgers, the music creator of South Pacific and all those great musicals, wanted to do a musical, and a producer — his name escapes me — came to us because he had an idea of doing The Mad Show off-Broadway so we gave him permission and Larry Siegel and Stan Hart wrote it. Well, they adapted a lot of stuff out of the magazine, and wrote a few originals. They were very fortunate because they got together a very interesting cast, which included Joanne Worley, who later went on to be one of the stars of Laugh-In, and there was Linda Lavin, who became the waitress in Alice.

Then there was Paul Sand. I mean, the cast was marvelous, and they all went on to do well, and the show sustained itself in this little theater, and it came in after another show was on, from 8:00 to 10:30, this show would go on at 11:00 or whatever it was, for a while, then it became full-time. It was at least a chalkboard for us to see what we could do. And that’s what I was excited about. But Bill had an interesting ... I don’t know whether it was a lethargy, or a fear, or what, but he made it very difficult for packagers of TV shows and movies to work with him. For example, he would not allow them to use any of our writers. He had a whole list, if somebody could find a copy of these impediments that he would set up, they would see why we never really got into any of this stuff. It was too discouraging. Not only that, but he wanted advertising approval of the TV shows. He didn’t want to advertise beer and cigarettes, which essentially were knocked off the air anyway. I mean, not beer, but liquor. He wanted actual approval for advertising. Well, that was the death knell right there. It might very well be that right now some cable people would be interested because they didn’t have advertising anyway, or at least some of them.

The very fact that the producers of Tales from the Crypt have had such a phenomenal success is kind of interesting too, and that of course was great for Bill and his ego because when EC, not Bill Gaines, but EC, which included me I think, was inducted into the Horror Hall of Fame, he didn’t even tell me about it. He didn’t invite me to the dinner. When he accepted the Horror Hall of Fame award, he thanked Lyle Stuart because he felt this was a culmination and a final vindication of his embarrassment at the hearings and of his terrible reputation that he had that finally all of this stuff that we had done was now being totally accepted. In fact, there were actors and directors who were dying to do this thing because it was such an “in” thing to do, you know? Schwarzenegger directed. You’ve seen the stars who have been in them.

RINGGENBERG: Oh. Sure.

FELDSTEIN: These HBO things, it’s interesting. And Bill even, I think he made sure I was no part of it.

RINGGENBERG: That’s terrible.

FELDSTEIN: Well, they were interesting final years together.

INFLUENCES

RINGGENBERG: As far as your science-fiction covers, who were the artists who influenced you? Chesley Bonestell?

FELDSTEIN: Yeah, well Chesley Bonestell influenced me with my covers, and also with my paintings because I’m trying to get that kind of very realistic style. Chesley Bonestell, as far as science-fiction landscapes were concerned, was my hero. As far as comic-book art was concerned, I really had no particular guy who I followed. I tried to develop my own style.

RINGGENBERG: Were there any newspaper strip artists who influenced you?

FELDSTEIN: No.

RINGGENBERG: Really? Well, it’s interesting you should say that because I’ve always felt your style was very unique. You really did not look like anyone else.

FELDSTEIN: As I told you at the outset, when I first got into this business, I had never read a comic book. I just borrowed a couple to make samples to get this job with Iger. In fact, I developed that philosophy with Gaines in the comics. I said to him, “Bill, we don’t want any artists to be imitating other artists. Just because Simon and Kirby are doing well doesn’t mean we should have everybody drawing like Kirby, or we should not have everybody drawing like X or Y or Z. We should have each guy doing his own signature.” That’s how we allowed Graham to do what he did in the horror and Johnny of course, did his style, and Jack Davis developed his own hairy little scratchy style. So I’ve always felt that people should ... That’s what made Mad and the EC magazines unique: All the artists had their own individual, recognizable styles.

RINGGENBERG: I think that was one of the reasons EC has been so well remembered and so influential.

FELDSTEIN: I think that was what made it collectible — they were unique and of course the stories were good. [Laughs.] You know, as I said before, I never really got too much credit. It’s been the collectors, guys like you and Jerry Weist and the rest who have probed into this, who discovered the true story because it’s not that apparent, even in the Cochran reprints. As a matter of fact, I only appear once in all of the Cochran reprints, my portrait, and that’s as the “Artist of the Issue.” They took new portraits of Bill, they took new portraits of Johnny even, but they never bothered with me, and I think that was a problem. I think Bill had gotten to a point where he really was kind of jealous of me or something. I’m not sure. I wouldn’t make any accusations. That’s one of the reasons why I went to San Diego this year. I had always refused to go to these conventions. Did you go to the awards dinner?

RINGGENBERG: No, I was there right afterwards.

FELDSTEIN: Well, there was an awards dinner and I was shocked I got an award for Lifetime Achievement. I didn’t expect it, you know? I told them all, “This is my first convention. I have never come to these before. Bill and I had a cash-and-credit arrangement. He paid me cash and he took the credit.” [Feldstein laughs.] I said, “But I decided I wanted to come and assuage my ego.” So I thanked them very much because you know, that was kind of nice. I never expected it really, and they treated me very well, and I’d be happy to do it again. As a matter of fact, I’m going to be doing a convention in Seattle only because my wife and I want to go up into the Canadian Rockies afterwards, or at least in that area, this summer in August, so I’ve agreed to appear in a convention in Seattle.

RINGGENBERG: Were you at the EC convention in 1972?

FELDSTEIN: Yes. That was the only convention I had ever attended. I was living in Connecticut at the time. That convention was a lot of fun. I was on a panel with everybody else and I was doing Mad at the time, but it was mostly about EC. Jack Kamen was there and Harvey, and it was fun. I enjoyed it ... And Bill was there. That was the only convention I had ever attended before the San Diego one. I won’t go down on my own expense. But I will go. They treated me so wonderfully. They put me up in this wonderful hotel, they picked me up in this stretch limo. I mean, my wife and I felt very, very special. It was just a fun time. I enjoyed being on the panels. I enjoyed my presentation and I was happy to see that it was well attended.

RINGGENBERG: Within the comics industry, your work is highly regarded by other writers and professionals who are in the know.

FELDSTEIN: You know, it’s funny. I’m kind of proud of my writing, but I was never particularly proud of my artwork, I always felt that the artwork was a little stiff, but it was stylistic. It did tell the story, so I did do the best I could. I was pleased with my science-fiction covers, but generally speaking, my figure drawing wasn’t that great. That’s one of the reasons why I was very happy to encourage other artists to join our group — then I could write for them and assist them in concept of the storytelling, but I wouldn’t, I even refused to do what Harvey was doing with Two-Fisted Tales and Frontline Combat, which was making tissue overlays and making everybody follow his layouts. I felt that would stymie the artist’s own creative ability, so I never did that. I would sit down with the artist and we’d go over the story. And there was no script. It was written right on the page, and I’d say, “What I had in mind here was, Joe is up on the cliff and he’s looking down at this or that.” He could take it from there. He could even show some below, or from above or halfway or whatever. That was the artist’s [choice], and I never had any qualms about giving them that kind of freedom.

RINGGENBERG: Do you have any thoughts on why you think people are still reading and collecting ECs 40 years after the company stopped publishing comics?

FELDSTEIN: I have absolutely no idea. I have often thought about it. I really don’t understand it. I don’t know why they’re doing it.

RINGGENBERG: Do you think perhaps the fact that you and Bill Gaines were trying to reach an older audience had some impact on the comics’ staying power? That the stories were a little more mature?

FELDSTEIN: Well, yes we were. We weren’t firing for any audience. I don’t know why that would intrigue people today. There are plenty of adult paperback books being written and all kinds of things. But at the same time, I have to admit it was at a time when there was a very small amount of television in our society. And that was a new medium and expensive, and I don’t know whether we would have been able to go where I wanted to go with the comics in lieu of the onslaught of television and its fascination.

RINGGENBERG: Do you think the high quality of the art had something to do with EC’s popularity?

FELDSTEIN: I guess so. You know, it was good-quality artwork. It wasn’t high-quality. You have to judge it on a level with what was being done at the time. There’s a lot of high-quality art I see in comics today but the stories are, you know, there’s something lacking. I’m not sure what it is. And they’ve got all kinds of weird ways of doing things too today, I understand. When we worked, we wrote a story, I put it down on the board the way I thought it should break down. I discussed it with the artists and that was that. Today I understand that they do outlines and then the artist takes over and then it goes back to a writer, and it’s kind of all, you know, hodge-podge.

RINGGENBERG: The Marvel style works from written descriptions, and then it’s penciled and then it’s dialoged and captions laid in.

FELDSTEIN: Yeah. I don’t know if that’s such a good idea. I think that the writer should have his control up to a point and then the artist should take over from there. But you know, we were also the first to realize that writing was an essential element of the success of a good comic book. That the stories had to have a quality to them and the writing had to have a quality to them even though it was a visual medium.

RINGGENBERG: Once EC really got rolling, did you and Bill strive for a sort of uniform tone for your whole line of books?

FELDSTEIN: What do you mean by that?

RINGGENBERG: Well, there’s a certain “EC feel.” Many of the stories, even if they’re not a horror story, like the science fiction or the suspense, have that kind of O. Henry punch ending. That seems to be a stylistic trait of EC.

FELDSTEIN: That I think was partially due to the fact that we plotted all the stories together and we as a team, Bill and I, had a feeling for the kind of story we enjoyed, which was that kind, with the snap ending, or the kind with some social injustice that we could chastise. And then of course I would write it. That may be part of it. We’re talking about the early ones before I started to use script-writers; it may have reflected my style of construction, because I did most of the horror stories and mostly all of the science fiction. It may have been my fault that it had that kind of uniformity.

RINGGENBERG: But it wasn’t anything conscious?

FELDSTEIN: The only consciousness I strove for was to improve the writing quality. I was very impressed with Bradbury when we got the rights to do his stuff. And as I was adapting his and writing my own, I think I was very affected by his styles and that may be why, probably why I got a little wordy. But, obviously, today, the kids are enjoying that, or not the kids, but the collectors are enjoying that.

RINGGENBERG: Yeah, it’s definitely an older market. I mean the kids are still reading comics, but there are a lot of older fans.

FELDSTEIN: The kids can’t afford to buy the comics. The collectors, they can buy... The San Francisco reprint crowd that did the reprints of the stuff, I don’t know who they are. And I don’t know whether the kids are discerning today. Geez, they sit in front of the boob tube and they swallow anything, you know.

RINGGENBERG: Unfortunately, a lot of the kids today seem to be hung up on what their collection is worth rather than just enjoying the comics.

FELDSTEIN: Well, I’m battling with that in my own personal life today. I’m painting now. I’m back doing what I started out to do before I ever became a comic-book artist and I had a scholarship to the Art Students League, and I was at the High School of Music and Art studying oil painting. And now I’m painting. I’m painting wildlife and Native Americans, Indians and landscapes and stuff. And I’m now involved with galleries and with selling paintings.

You’d be surprised how many people buy a painting for what they think it’s going to be worth down the road, not because they really love it, you know? And there is, I’m sure, a parallel with the comic-book collectors today that are buying because they think it’s going to be worth something more than what they’re paying for it, rather than enjoying the product. I’m wondering, you know, and I think it’s kind of sad that some of these guys buy an old EC comic and put it into a plastic envelope and never open it and look at it because they’re afraid to damage the mint condition of it. So it really becomes a commodity rather than a source of entertainment.

RINGGENBERG: That’s one reason I think it’s good that Russ Cochran and the other people are putting out the ECs as regular cheap comic books in color, so if people want to just read it and enjoy the story, they can.

FELDSTEIN: Is Cochran doing that? I thought he did the box sets. I thought someone else was doing the color comics.

RINGGENBERG: He did the box sets and he started the color comics. I think Russ retired now.

FELDSTEIN: Yes, I know that.

RINGGENBERG: But that’s being carried on.

FELDSTEIN: Good! Then you see, at least they can buy those and read them. They don’t have to worry about the value of them being destroyed or the fact they probably will not reach the value of the originals. But you know, you can’t fault collecting of scarce material whether it be postage stamps or an original comic book. It’s a phenomenon that is a part of our culture, and the Franklin Mint and the plate manufacturers are all doing that, even these people who put out these plates, for example, kind of hint that it’s going to be more valuable, like you can enjoy it, but it’s also going to increase in value. So we live in an investment, capitalist society, and that’s the game.

ALL MY FAVORITE ARTISTS

RINGGENBERG: Who were your favorite artists with whom you worked?

FELDSTEIN: They were all my favorite artists. I really wouldn’t ... Jack Davis was great in his kind of superficial horror. Ingels was great in terms of the real classic horror. Are we talking about EC, or the Mad times?

RINGGENBERG: Well, among the EC artists if there were any you particularly liked, and then when you were doing Mad, was there anyone you particularly liked?

FELDSTEIN: No. I loved them all. I really did. They were all so talented, and they all handled everything so well. Bill and I were starting to write specific stories for specific artists based on their style and what they did well. Kamen always did the domestic-violence type of thing with the wife and the husband and the kids, because he did this kind of Marcus Welby-style of drawing, you know? The American family. And Graham always did the corpses and the classical dripping things.

RINGGENBERG: With Graham Ingels, I was curious. Why do you think he dropped out of sight after the EC days?

FELDSTEIN: I think Graham had a problem. I had heard that he had an alcohol problem.

RINGGENBERG: I had heard rumors of that, but I never really heard anything definite.

FELDSTEIN: I wouldn’t make any statements, because I really have no knowledge. I know that he had difficulties even when he was working for EC.

RINGGENBERG: I think what I had heard over the years was that Ingels was living in Florida and teaching painting.

FELDSTEIN: Yeah, well he was a fine artist and Bill Gaines had a wonderful painting of his of the Old Witch.

RINGGENBERG: I was in Bill’s office and I saw that painting, and I also saw a science-fiction painting you did. It was a landscape.

FELDSTEIN: Yeah, right.

RINGGENBERG: Was that something you did just for fun?

FELDSTEIN: I did that for Bill because he had come to my home and I had not done much in the way of straight art as I worked for EC and Mad, and it wasn’t until I retired and have gone back to it now that I’m doing it full-time and doing a lot of it. But right after the war I had done a landscape, a kind of moody landscape that was reminiscent of where I was in Blytheville, Ark., of an old beat-up shack with a rutted road and an old dusty tree with moss on it. Bill walked in, picked up that painting and said, “I want this.” So he took it.

I let him have it for a while, and then I thought, “Gee whiz, what’s that doing in there anyway?” So I said, “I’ll make a trade with you. I’ll trade back that painting and I’ll paint you a science-fiction painting.” And that was the painting you saw. I painted that for him. It was my first science-fiction painting, and the precursor of the kind of thing I’m doing for Jerry Weist for Sotheby’s.

RINGGENBERG: Interesting. Al, just to backtrack again, when you took over Mad after Harvey left, were there any subsequent ill feelings between you and Harvey?

FELDSTEIN: Absolutely not. As a matter of fact, here’s another story, which is not of public knowledge. Harvey went from Trump, which failed not because of his editorship or his abilities, but because Hefner became overextended — thank goodness [laughs] because it was good for us, it was good for Mad that we were surviving and they stopped. Harvey then went on to do Help! and ...

RINGGENBERG: Humbug.

FELDSTEIN: Right. Humbug was first, then Help!. Humbug had failed, and he was doing Help!, and I said to Bill Gaines, “You know, Harvey worked so well when he was part of our organization.” One of the reasons that Mad was successful was because we bounced things off him and kind of chided him into staying on track, and when he went off track there was a lot of kibitzing. I said, “Why don’t we bring him back into the organization? Mad’s, Mad, but let’s bring another magazine in. If we got Harvey to come back and we backed him and gave him his head with Help!, he could do the adult and I would do the kid magazine, or vice versa, make Mad more adult. It would be good. Like the soap companies have all their own competition, you know? Why don’t we bring him into the fold?” So we went down to the restaurant and he and Harry Chester and Bill Gaines and I met and we offered him this deal: Come back, let us publish Help! for you. You be editor, it’s your baby. Let us help you distribute it, help guide you. But he wasn’t having any part of it.

RINGGENBERG: I never heard that before.

FELDSTEIN: [Laughs.] Yeah, well, there are things that nobody has talked about. That is one. That was my idea, and we had this lunch and Harry Chester and Harvey said no. I guess they were afraid we would take it away from [them]. I don’t think Harvey trusted Bill, I don’t know. But I was open to it, because I thought it would be a wonderful thing to have — to have a publishing company with several different kinds of approaches.

RINGGENBERG: I know Harvey came back and did some freelance work for Mad.

FELDSTEIN: That was much later. That was even after I retired. It was when Harvey was on the balls of his ass financially, and Little Annie Fanny had been dropped from Playboy, which was his mainstay income-wise. So he came back and started to do work for Mad again, which I thought was very sweet and kind of Bill to allow him to do that, although I think at that time he was already beginning to suffer a little from his physical problems. That was after ’84. I retired in ’84. I once tried to get Bill Elder to come work for me but he refused because he was afraid of antagonizing Harvey.

RINGGENBERG: When artists like Davis and Wood returned after leaving with Kurtzman, was it a little awkward?

FELDSTEIN: Wood never left.

RINGGENBERG: Wood continued working for you and Harvey.

FELDSTEIN: Wood never worked for Harvey.

RINGGENBERG: I thought he worked on Humbug.

FELDSTEIN: Oh yes. Maybe, I don’t know. He did?

RINGGENBERG: Yes. I know he also did some work for Trump.

FELDSTEIN: Wait a minute. He worked for Humbug after I let him go. After he no longer worked for Mad. Wood never left to go to Hefner, to Trump. Wood was one of the first artists I acquired when I took over and he did that little mouse thing, you know, that space thing about sending up the mice. But Wood had a problem too. I was a consummate professional, and I only wanted to work with consummate professionals.

RINGGENBERG: Is that why Wood started doing less and less work and then eventually stopped?

FELDSTEIN: Yeah, he wasn’t dependable and I had deadlines. You can’t hold up a press with a 400,000 print run for more than a day. I mean, if he wasn’t going to make his deadline I just couldn’t. As a matter of fact I absorbed all that when I was editor of Mad. I developed an inventory of almost three issues, which was partially my desire, and partially how I felt about writers and artists. Any artist who finished a job always had a job waiting for him when they came back, because I was very empathic to the freelance artist’s needs. Also, any writer who gave me a good idea, I would have them write it, regardless of whether I needed it or not and I’d stick it into inventory. Bill was aware of it, but I don’t think he was really aware of the financial amount of money we had in the inventory. It was well over three issues, I think closer to four issues probably, which means close to 200 pages.

RINGGENBERG: Well, I guess given Mad’s success at its peak, that was no problem financially.

FELDSTEIN: Yeah. And from my point of view, it was great. I could go on a vacation and also, when it came time to make up a magazine, I could balance it well. The only things that I put into inventory was stuff that wasn’t timely; anything timely was scheduled immediately. But as far as the inventory articles were concerned, this was two things: It was good for us editorially, it was good for the artists and for the writers. It really wasn’t that much money invested.

RINGGENBERG: When Davis returned after leaving with Kurtzman, was there any awkwardness?

FELDSTEIN: Maybe on his part. I was happy to see him. I was a freelance artist and a freelance writer so I know what it’s like. You’ve got a wife and kids and a mortgage. You’ve got to go where you can make money. If you’re going to let your feelings get in the way and say, “Well, you went with Harvey so I’m not going to take you back,” that’s dumb. That would be cutting my nose to spite my own face. Jack Davis was a fantastic artist. [When he came] back to do “The Man In the Gray Flannel Suit” for me I was delighted. I think he felt a little awkward and also I think he was worried too, because he never really liked the horror stuff. He was kind of embarrassed about that.

RINGGENBERG: He has mentioned that in interviews.

FELDSTEIN: Yeah. But he was still one of the best, and he did the job great. But then he was a consummate professional, as I said. He’s the guy who I wanted to work with. When he did a horror cover, he did a good horror cover. When he did a science-fiction cover, it was good. He was a pleasure to work with, and when he came back, I’m not sure who approached who, but I was delighted to have him, and the same with Al Jaffee.

RETIREMENT

RINGGENBERG: After working on Mad for 29 years, did you ever have a period when you were feeling absolutely burned out by it?

FELDSTEIN: Well, that’s when I decided to retire. I was not burned out. I was never burned out, I was more kind of bored. There wasn’t enough challenge to fill the magazine. I thought basically I had done every kind of approach to satire I could think of. We were the first guys to do the coloring books which later some other publishing companies published, like the JFK coloring book. We had been doing coloring books in Mad, we had been doing primers, we had done all of these different kinds of formats presenting satirical concepts and I was starting to feel limited.

I would have loved to have been able to do television or movies or tapes or the stage, theatricals. So that was part of my desire to leave. I also felt that, and I had made a lot of money, I felt that there was more to life, and I thought I had enough. I was not wealthy, but I had enough to retire. I could buy some tax-free bonds and have a fairly decent income if I didn’t live in New York in a fancy co-op apartment as I had, so I decided to retire. And that’s why the last contract was only three years.

RINGGENBERG: From the sounds of it, it seems like you’re enjoying your retirement.

FELDSTEIN: Oh, absolutely. This is a dream for me. I’m painting. I have my own studio, which I added on to this ranch house. I paint in the winter and during the summer-time I fly fish. I’ve got horses, I ride, and it’s just great. We live in a fantastic area. I don’t know if you’re familiar with the valley that’s north of Yellowstone National Park.

RINGGENBERG: I’ve been to Yellowstone.

FELDSTEIN: Well, this is north of Yellowstone National Park. It’s called Paradise Valley. It’s where the Yellowstone runs up north in Montana and then turns east in Livingston. We’re 14 miles southeast of Livingston. We have the Absaroka Beartooth Wilderness looming over us in the east and the Galatin Mountains looming over us in the West. We’re in this valley and it’s just spectacular.

RINGGENBERG: Do you winter up there?

FELDSTEIN: Yeah. I only have this one place and we’re very comfortable here. Yes, we get snow, but it isn’t as bad as it was in Jackson Hole. I first moved to Jackson Hole from Connecticut. My wife and I came to Jackson to go skiing and we fell in love with it. We bought a house four days after we were there and sold the place in Connecticut. But Jackson became a little too much. It wasn’t exactly what I wanted. The people who were coming in were coming in for the wrong reasons, I thought. I left my urban life, I changed my life to a western thing, but a lot of the people were coming from California or New York or wherever and they were bringing their philosophy with them. They wanted to put in ornamental shrubs and lawns and get rid of the deer and the moose, and I loved this wildlife. I was painting it.