It is important to note that when Sakai’s name first comes up in Tezuka’s diary, it is as a former animator. “I liked Sakai Shichima’s drawings the best,” he wrote on June 21, 1946, after attending his first Kansai Manga Man Club meeting. “Just as I thought, Sakai used to work on animation.” He saw the animator in the cartoonist. Manga eiga (“manga movies”) became one of their favorite topics of conversation. No specific titles or artists are named. Given their mutual interests, it’s hard to imagine that Disney didn’t come up. Some scenes in New Treasure Island are based directly on old Mickey films, as I will show in a future essay on the adaptation of small-gauge filmstrips in early postwar akahon. For now, let me demonstrate how the mutual interest in “animated Disney” can be motivated in a different way.

In the literature on New Treasure Island, the terms “cinematic” and “Disney style” are used frequently. Traditionally the two are considered separately: simulated camera work and editing, on the one hand, Disney-esque stylized characters, on the other. But as I argued previously, once you factor in the influence of American comics, it becomes clear that the two went together, at least in the case of New Treasure Island. One of the comics that underwrote the manga, after all, was Donald Duck Finds Pirate Gold, a Disney comic based on abandoned animation storyboards.

So the question of authorship should not be which of the two collaborators was more likely to experiment with a “Disney style” side by side with “cinematic techniques.” But rather who was more likely, in 1946, to have experimented with these two as an indivisible pair? Was it the young cinephile who had explored both but independently in his practice works of 1945-46? Who, to my knowledge, never spoke of Disney and the “cinematic” in the same breath? Or could it have been the practiced animator, who not only had actually made animated movies, but animated movies influenced in multiple ways by the popular black and white Mickey Mouse films of the late 20s and early 30s?

A number of writers have described the first pages of New Treasure Island as more precisely in a “storyboard style” rather than a generally cinematic style. But the matter is left at that, as if all storyboards were the same. When it comes to describing what’s inside the frame, terms like “close-up” and “changing perspectives” are commonly used, with little attempt to anchor the vocabulary to any specific precedents. Furthermore, it is conventional to speak of the entire spread as innovative. Indeed nothing like it exists in contemporary manga. However, it is important to see that there is something very old about this sequence, and it is precisely this retrograde element that I think points back beyond the Occupation, beyond Tezuka’s wartime work, and into the vocabulary of early 30s animation, which is to say, Sakai and not Tezuka’s world. The new side, meanwhile, comes from neither movies nor animation directly, nor even older manga, but instead from American comics, which was probably serving, as I will explain below, as a surrogate for problems in the animation of movement. Put simply, my sense is that the dynamic representation of Pete’s driving stems not from formal sensibilities inspired by cinema, but rather from problem-solving in animation.

There are four panels on the first two pages, each showing Pete driving his roadster from a different angle. The first two show him driving at oblique angles to the picture plane, subtly toward in the first panel, more sharply away in the second. The second two panels show him driving at right angles to the picture plane, first directly towards the reader, and then parallel. Eight o’clock, ten o’clock, six o’clock, nine o’clock – the variety is deliberate, and bespeaks a certain kind of strategy for getting drawings to move.

It is well known that diagonal movement is a tricky problem in animation. When an object moves away from the picture plane at any angle, the animator has to attend carefully to continuous changes in foreshortening. This is also the case in movement directly towards or away from the picture plane, but the hassle of foreshortening in that case can be short-circuited by “looping” both the background and the cel, but at different rates so that the background appears to run like a treadmill beneath the cel figure. Even the casual watcher of old animation should recognize the common use of this device.

As a practicing animator in the mid 30s, Sakai of course knew this trick. He had used looped vehicular scenes of a similar sort in Ninja Fireball Kid in 1934-35. It is probable that Tezuka also knew them through theatrical screenings or his small-gauge film collection. Strict perpendicular movement toward the picture plane, requiring foreshortening, was also common in that era. It was one of the common jokes in the early Mickey shorts, with mooing cow udders or Minnie’s screaming mouth barreling toward or away from the viewer. Sakai used this too in Ninja Fireball Kid. Nonetheless, the opening sequence of New Treasure Island has few markings of humor, so I think it more apt to think of the third panel as a frame from a head-on loop.

In the third and fourth panels, one thus has vectors associated primarily with animation of the 20s and early 30s. It is for this reason I call them “old.” Considering their relative ease of representation in animation, one might prefer to call them “elementary” or “conservative.” Regardless, they belong to a specific era of formal thinking about how to draw movement, and specifically how to do so within animation. It is telling that, in the 1000-plus pages Tezuka drew prior to New Treasure Island (published and unpublished), rarely does one find any kind of direct movement toward (or away from) the picture plane. And even more rarely is it designed to bear down on the viewer. Here is a possible exception.

Lateral movement is common as early as 1945, but strict perpendicular movement does not become a regular feature until later in the 40s. Looking at his wartime juvenilia, one gets the sense that Tezuka’s “cinematic” thinking was largely determined by live action film, the movement of figures through space captured by a stationary camera, and the building of narrative through the montage of fragmentary shots. One might make an argument for precedents in Tezuka’s wartime work for the first, second, and fourth panels in New Treasure Island. But the third is fairly alien to his working method at the time. It is too old-fashioned, I think, to have been conceived by Tezuka.

If the right angle is the vector of animation, so to speak, then what is the diagonal? It could also be animation, of course, because diagonal movement does exist in the medium, though handled sparingly and often awkwardly by most studios until the late 30s. But in the somewhat archaic thinking of the designer of these pages, I think the diagonal was seen as a fascinating “problem,” a vexing element that requires exceptional skill and practice, and an attraction worthy of replicating, multiplying, and placing front and center once mastered. Young Tezuka loved the diagonal, with characters typically looking out over the reader’s shoulders, and rarely eye to eye. But when it comes to moving vehicles and figures, the diagonal perspective is either rendered in a kind of orthographic space in which foreshortening is not an issue. On one occasion in The Ghost Man (1945), the result broadly evokes the opening scene of New Treasure Island.

Or more typically the diagonal is coupled, not with an image of the same object from another angle, but with a countershot showing where the moving object is headed or what its operator sees. Again, this is essentially a cinematic approach, focused as it is on visual narration through editing. The first pages of New Treasure Island, on the other hand, suggest instead a fixation with the dynamic portrayal of movement itself. Changing perspectives are designed to increase the sense of movement. Their primary function is not narrative.

More than once, Tezuka claimed that the “cinematic” element of New Treasure Island stemmed directly from his experiments with adapted camera work during the war. If this is already doubtful from a purely empirical comparison – nothing like Pete’s driving or the river crossing appear in his previous work – it becomes simply unbelievable once we learn that Disney comics provided the primary model for the dynamic diagonal in that manga. It is appropriate that they should have come from Disney comics, for these comics have a stronger relationship than most to the art of animation.

I do not doubt that Tezuka’s wartime “cinematism” was a major force behind New Treasure Island and the way Disney comics were adapted within that manga. What I do question is the widely-held assumption that his was the only artistic intelligence at work.

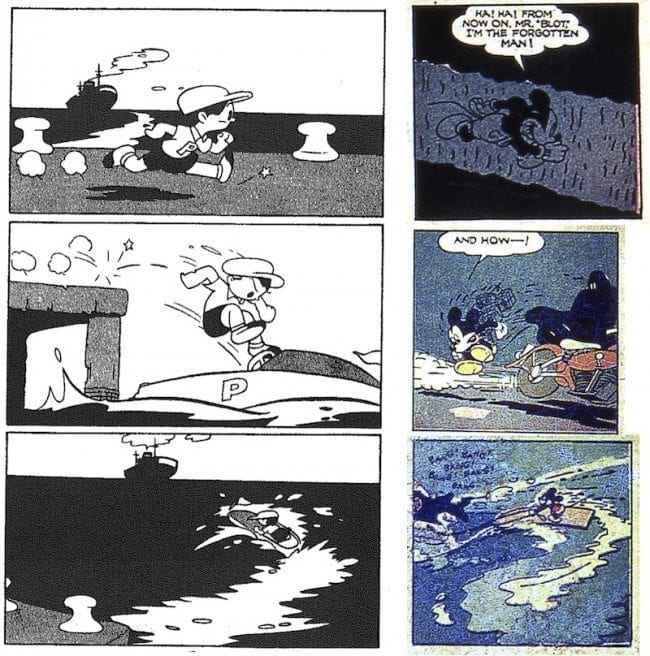

It turns out that not only the first two panels, but also the horizontal fourth, and further most of the panels on the next three pages, have been swiped from Floyd Gottfredson’s Mickey Mouse Outwits the Phantom Blot. Though originally a newspaper continuity in 1939, one assumes that Sakai and/or Tezuka knew this work instead through its reformatting as the very first Mickey Mouse One Shot from Dell, published in 1941. It is curious that both this comic book and Pirate Gold were four-five years old by the time they were processed in New Treasure Island. Were old comics being brought into Japan after the war, after circulating elsewhere (at bases, on ships) during the fighting? Were the early Dell Disney comics being reprinted after the war?

By the time of The Phantom Blot, Mickey has fully shed his adolescence and bumpkin roots. He is wise as well as clever. He is bratty rather than nasty. He lives in the ‘burbs. He no longer drives a lemon, yet as his tree-ramming in The Phantom Blot shows, he is not to be trusted behind the wheel even when the baby purrs. He takes on villains that might still be mass entertainment clichés, but now they are clichés of contemporary social bearing. Such is the case with the Blot, a rendition of the old shadow men of the pulps and the movies – “always togged out to look solid, dead black, with only his eyes showin’,” in the words of Gottfredson’s Police Chief O’Hara – but as a foreign spy also an expression of anxieties concerning conditions in fascist Europe.

Who the Blot is, however, is beside the point. And that is because he himself does not appear in New Treasure Island. It is Mickey that has been appropriated. He zips around in his car often during the story, usually while chasing or being chased by the Blot. Mainly these are the scenes that Sakai and/or Tezuka have used.

Of the first six pages and sixteen panels of New Treasure Island, nine of them have definitely been inspired by The Phantom Blot, with one or two additional panels possibly generally so. Of the first four pages and ten panels, all but two are not derived from that source. Of the first two pages and four panels, only the panel discussed above comes from elsewhere. And tellingly, on the same page that the Blot-based panels phase out, those from Pirate Gold begin. If Hello Manga greeted children with the most elementary English salutation (Haro!), New Treasure Island does so with a Disney parade. If Hello Manga taught children how to spell Japanese words in Roman (American English) alphabet, New Treasure Island tried to reconstruct manga for the American age on the basis of Disney building blocks. Disney was the A-B-C of this new American manga.

The first panel of New Treasure Island comes from a sequence in which Mickey is tearing away from some locals after swiping one of their cameras, a clue to the Blot’s activities. Most of the rest comes from the comics’ finale, and primarily from a single two-page spread. Mickey has escaped from the Blot’s imprisonment, and is now hurtling in his car to the harbor, where the Blot hurries to exit the country on a seaplane. From this single two-page spread, Sakai and/or Tezuka have taken compositions or motifs from five panels, showing Mickey driving and jumping from his car, trailing behind the Blot’s speedboat on a surfboard-type thing, and then leaping to catch the wheel of the Blot’s seaplane as it lifts into the air.

There are changes: the style of the car, the surfboard for a speedboat (which Mickey obtains also in the original, just in a different scene), the seaplane’s tire for a ship’s rope. The drawing has become broader. The key change, however, is the layout. Gottfredson’s irregular 2x3 layout has been simplified and regularized for the strict 1x3 of New Treasure Island – an old template, dominant in children’s manga since at least the early 30s, and which would largely disappear in the late 40s with the eclipse of akahon’s golden age and the ascendancy of the varied layouts of 40s American comics.

In addition to the famed vehicular action, Sakai and/or Tezuka have borrowed some of Mickey’s facial expressions (transposed to the first panel of New Treasure Island) and distinct body poses (Pete kneels on the wharf as Mickey does on the surfboard in the bottom left panel). How Pete runs on the wharf, and how he jumps into his speedboat, have been derived from elsewhere in The Phantom Blot, from scenes showing Mickey running through a secret underground passage and jumping from the sidecar of a motorcycle. Note the attention to detail: Mickey’s distinctive backward cupping hand reappearing upon Pete.

Once again, as was the case with Pirate Gold, we can see here that “Disney style” encompasses a whole system of expression, from how characters move and hold their bodies, and how they express emotion and the stereotype of rounded contours and deleted digits, to even the holy grail of “cinematic” techniques. Which is to say, “Disney style” meant nothing less than making comics in American Japan. If New Treasure Island was at the cutting-edge of various formal developments in the medium, it was also at the avant-garde of a wider project of cultural assimilation.

(Continued)