When did Tezuka shift his weight from the Pathé Baby and prewar Disney books to the Disney comic books from Dell and Western?

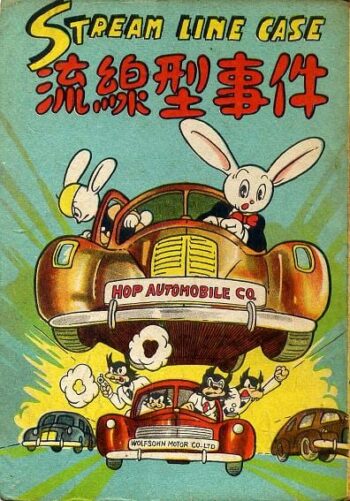

Some of his early akahon from around 1947 and 1948 suggest that he still might have been using the Pathé 9.5 mm films as reference. By The Streamline Case of October 1948, Disney comics have clearly been absorbed from head to toe, with heavy appropriation from the early issues of Walt Disney’s Comics and Stories. In January 1947, New Treasure Island showed that Tezuka was already heading in that direction. That I will deal with later.

For now, when was first contact made?

If we are to believe one of the artist’s many origin stories, the one that is most specific on the matter of when he first started reading American comic books, then the answer is the spring of 1946. The occasion of this origin story was an anthology of essays by famous Japanese on the subject of Mozart, published in 1976. One might expect the topic to send the writer down an armchair trip through the halls of cultured Europe, but Tezuka instead finds himself in the Occupation.

It was the spring of the year after the defeat, and I was a student at the Osaka University Medical School. In the building next to my department was the YMCA, where they kept a piano. I would oftentimes skip lectures and occupy that room and play it.

Keep in mind that Osaka after the war was occupied, like the rest of Japan, by the American military. Everyone assumes that of course, but I think it is still an underappreciated fact in assessing the reorganization of manga after World War II. Tezuka’s art is often linked to prewar manga and animation, to his hometown of Takarazuka and its theatre of melodrama and gender-bending, or to the dark clouds that continued to hang over Japan under the American nuclear umbrella. Only really writer Ōtsuka Eiji has taken the Occupation context as a primary one in understanding Tezuka’s early work, but even there it is more about politics and Japanese identity during the early Cold War than the mundane but forceful fact of Americans being physically in Osaka until the end of the 50s. One typically thinks of Okinawa or the Tokyo region when it comes to the American military in Japan, or the isolated camps in Misawa to the north or Iwakuni to the south. But for most of the Occupation, many major buildings in downtown Osaka were used as administrative offices and service facilities by the American command. The largest area camp was Itami Air Base, located approximately ten kilometers of city center and returned to the Japanese only in 1958. To the east of it was the officers housing of Camp Toneyama. And to the northeast of it in turn was Osaka University, where Tezuka studied medicine between 1945 and 1951.

One day, completely in my own style, I was playing Mozart’s Turkish March. All of a sudden a Black soldier entered the room. There was nothing really strange about an American soldier being at the YMCA. He took a sheet of music from the piano, and once I was finished playing began to sing in tenor.

It was something that I had heard before. It was a march. Eventually I realized that it was the aria “This Butterfly Shall Fly No More” from The Marriage of Figaro. To a Mozart piece, he had responded with a Mozart aria. He was a great opera fan, this intellectual Black soldier named Joe. . .

One day, after learning that I liked cartoons when I drew a quick caricature portrait of him, he brought me a mountain of American comic books. It was like the heavens opened and rained manna. There were absolutely no manga materials around at the time. I read through them like a worm, was overjoyed, and copied them obsessively. . .

My friendship with him might have been short, but it became the reason I decided to become a manga artist.

Again, this is the spring of 1946. The date as Tezuka recalls it seems accurate enough, as the works he made in the second half of that year show ever-increasing influence from Disney comics.

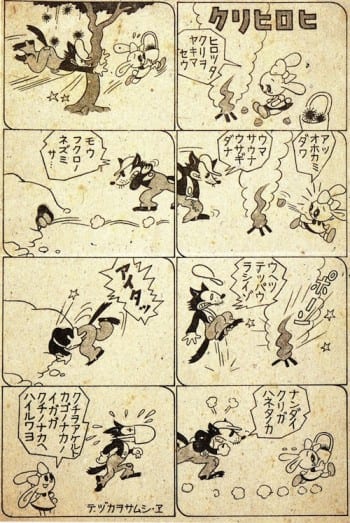

For example, all of sudden towards the end of 1946, there appears in one of his strips for Hello Manga Disney’s Big Bad Wolf chasing a rabbit. One imagines that he was looking at Walt Disney’s Comics and Stories, many issues of which through 1946 included a handful of pages with the L’il Bad Wolf. From INDUCKS I see that the March 1946 issue is nicely timed with a story in which Big teaches L’il how to catch, just that, a rabbit. Some research to be done here.

“So it sounds like you had collected a fair number of Walt Disney’s Comics,” said Ono Kōsei to Tezuka in an interview on the topic of American comics for the Japanese edition of Superman in 1979. “Yes, I have quite a few,” responded Tezuka in the present tense.

“So it sounds . . .” Ono was actually responding to this.

When Superman and Batman came to Japan, it was right after the war, right? Together with the G.I.s. In other words, our height and theirs was completely different. We were totally overwhelmed physically, and got this complex about being unable to compete with White people. It was just then that Superman arrived, the White man’s representative, and I thought who the hell does he think he is? And then Lois Lane, the classic American beauty. Even her outfit and her makeup were like a foreign woman’s. Of course today Japanese make themselves up more like foreigners than foreigners do. Ha ha ha.

Again, a caution that this is all said about thirty years after the fact.

Ha ha ha. But at the time, everyone in Superman looked like an alien from another planet. Compared with that, Mickey Mouse was just an animal, and so was easier to use. That’s the side I got consumed with. So just maybe, had I felt more in common with Superman, my drawing style would have been different.

Of course, Superman wasn't totally untouchable for Tezuka during the Occupation. A compromise was reached in 1951 when he put the flying “man of steel” in Pinocchio and Mickey Mouse’s body, resulting in Atomu, the cute nuclear-powered robot who fights evil but wants nothing more than to be a human boy.

But already much earlier one can see that Disneyfication for Tezuka, despite his later assault on Walt as ambassador for Cold War Uncle Sam, was a way to accept the Occupation. When a selection of the Little Ma strips were redrawn and published as a slender children’s book in July of 1947, it came with a strange cover. Little Ma now clearly has four fingers to go with his Mickey gloves. His button is now right in the middle of his chest, for no good sartorial reason. His eyes are now pied, where once they there were solid black ovals. And now he is comfortably in the arms of an American G.I.

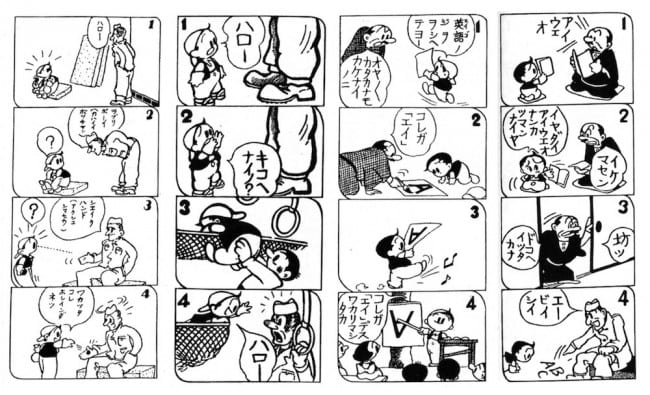

Many of the Little Ma strips of January to March of 1946 – before contact with “Opera Joe” and his comic books – have the little Japanese boy socializing with American servicemen. He is attracted to them and their language. He shows little interest in learning his katakana characters while becoming magnetized at the sight of the ABC’s. But there are communication problems. Because of language, because of customs (he does not understand the handshake), and because of their towering height, there is a distance between him and the giant high-nosed foreigner. He does not know when the letter “A” is upside down.

But now, one year later, on the cover of Little Ma’s reissue, it would appear that these distances have been bridged. This G.I. holds Little Ma up high, rather than looking down at him below. This G.I. does not have a big ugly nose. There is not any sign of miscommunication between the two of them, as Little Ma rejoices being in the American embrace with wide-open arms. What has made them so suddenly familiar? The American soldier now also has gloves, now also has four fingers, now also has pie eyes. Certainly one cannot describe this cover as done in a “Disney style,” but nonetheless a degree of Disneyfication seems to have made “the American” acceptable.