Gary Groth interviews the seminal gekiga artist Yoshihiro Tatsumi.

From The Comics Journal #281 (February 2007)

Yoshihiro Tatsumi is a pivotal figure in the history of manga. Like American comic books of the same period, manga in the ’40s and ’50s was dominated by a juvenile idiom. There was good work done within the parameters of this idiom, but to an artist with serious aesthetic ambition, it was too confining, indeed stifling. At about the same time that a handful of cartoonists in the U.S. — Kurtzman, Eisner, Krigstein — were bucking the trend and trying to create work that was more literate and graphically sophisticated than the editors and publishers wanted, the aesthetically restless Tatsumi broke from the industry norm in Japan and started making comics of an intensely personal kind. In 1957, he began writing and drawing comics that he called gekiga (literally “dramatic pictures”), which exorcised his own private demons and reflected his intensely subjective perception of the world around him. He still had to make a living by drawing commercial comics (and even became a commercial comics publisher himself) but continued to draw his own comics when he had the time and an outlet.

The first (authorized) English translation of his work came out in 2005: Push Man and Other Stories, edited by Adrian Tomine and published by Drawn & Quarterly. A second volume of short stories came out last year. In late spring of ’06, D&Q’s publicist Peggy Burns called and asked me if I’d be interested in interviewing Tatsumi at Comic-Con International in San Diego in August. I got back to her after I’d looked through — but not read — Push Man and agreed to interview him. Cursory research indicated Tatsumi was a fascinating historical figure, and the work looked meaty and interesting. We set up a time and a place and secured a translator.

In the interests of full disclosure and critical honesty, I should say that after I’d read Push Man, I had misgivings over his work, which were not allayed by reading the subsequent volume, Abandon the Old in Tokyo, which seemed to me largely supererogatory. Greg Stump in his accompanying essay, points out how relentlessly, uncompromisingly bleak Tatsumi’s stories are. And indeed they are, but this isn’t by itself a recommendation any more than a happy ending is reason to condemn a story. Although there have been exceptions, I usually only interview artists whose work I like, and I didn’t feel entirely comfortable interviewing Tatsumi. I was troubled by a number of tics that comprised the backbone of Tatsumi’s aesthetic: the narrowness, aridity and sameness of the vision; the dramatic implausibility and jerry-rigged mechanics of many of the stories; characters who are either stereotypes or ciphers (albeit purposeful ciphers); and a tendency toward heavy-handed, literal-minded metaphors (the rat in “My Hitler,” the piranhas in “Piranha”).

That said, the work was clearly a sincere expression of Tatsumi’s convictions, and his artistic choices, whatever my reservations, took courage and tenacity; I thought I could do a good job and looked forward to interviewing him. Tatsumi’s schedule was booked solidly throughout the convention; the interview was supposed to take place Saturday afternoon between public appearances at the con. I hadn’t quite reckoned with how cumbersome and time-consuming the translation process is; I would ask a question, which would be translated into Japanese; Tatsumi would answer in Japanese, and the translator would translate it for me into English. The interview therefore yielded less than half the conversation of an interview where both parties speak the same language. When we had finished lunch, I asked him if he’d be willing to continue the interview in the early evening after his last convention panel (and before dinner), to which he agreed. We clocked in over five hours of taping altogether.

Physically, Tatsumi is a compact man with a gracious manner (and obviously patient); his conversation is straightforward, and his sense of humor was, well, given his work, surprising. I’d like to think we got along well. I would especially like to praise our translator, Taro Nettleton, whose translation reflected the talk’s colloquial nature, and who navigated the ebbs and flows and back-and-forth of the conversation expertly. I hope this interview serves as both an introduction and deepening explication of Tatsumi’s life and work.

— Gary Groth, January 2007

GARY GROTH: I’d like to begin by getting a little background information. You were 10 years old when World War II ended, and I wanted to know what your recollections of the war were, and how you think the war affected your later life and your perceptions of life.

Yoshihiro TATSUMI: Obviously, since I was 10 years old, I didn’t go to war. But it was still a very immediate experience, so I watched my neighbors’ houses being burned down. I watched landscape get turned into rubble, firebombing by firebombing. And luckily, my house, my family’s house, was not burned down, but I saw corpses firsthand, everywhere on the streets. So, the tragedy of the war inevitably influenced my experience.

GROTH: What city did you live in?

TATSUMI: I lived only about 10 minutes away from Itami Airport. The airport was a target, so my house actually had a couple of bullet holes going through the walls. One of the things that was most unforgettable was the scent of the rotting corpses on the streets. That they would be left there for days on end, and to this day, I can’t forget that, the smell of rotting flesh.

GROTH: I assume that that was a pretty deeply etched part of that experience. Did that affect your later aesthetic sensibility?

TATSUMI: Well, what really was ingrained in my mind was the juxtaposition between ugliness and beauty, wealth and poverty, and this idea of the outside and inside and the discrepancy between the two. And so even when Japan started to enjoy economic growth —

GROTH: — Prosperity?

TATSUMI: — prosperity, I was still unable to shake the feeling that this was only a façade and right beneath the surface was all this kind of ugliness still.

GROTH: Do you think that that is empirically true, or merely your perception? Have you investigated this?

TATSUMI: It was true to my own experience, and for me, I started really writing comics in my 20s, and I’ve always targeted my work to readers of my own generation. So, for my intended readers, I think that this was a certain kind of truth, but perhaps for younger generations of readers, they may have felt some discomfort or alienation from this kind of depiction.

GROTH: What was your experience as to how people behaved during and after the war?

TATSUMI: It seemed to me that while the public was very ready to forget the past and move on from the war, for me it was extremely difficult to let that go. And so even today, when I visit the United States, I can’t help but think of World War II, in a sense. Especially in San Diego, because of the strong military presence here, and there’s been Japanese politicians coming to inspect the nuclear carriers. It’s very difficult to separate the two, kind of the past and the present. This is my first time in the United States. Actually being here, I feel San Diego is a beautiful place, and I feel comforted, almost enough so that I can forget the past.

GROTH: When you say that it’s hard to forget the past, do you mean that you harbored an animosity toward the United States about the war?

TATSUMI: No, I don’t harbor any animosity against the United States. Although, as a child during the war, we were all taught that the Americans were the devil, you know, that they were evil.

GROTH: The usual demonization, yes. [Laughter.]

TATSUMI: But immediately after the war, the reality was that we had no food, and we went to the soldiers. It’s sort of a famous phrase in Japan — that children would run up to the soldiers and say “Give me chocolate, give me gum.” So, I had direct contact with the soldiers, so that definitely worked toward changing the ideology that I was taught. It really changed the way that I felt about Americans. It’s not included in this work, but I actually have a story that deals with my childhood experience in the immediate postwar period.

GROTH: Is that right? Depicting children. This is autobiographical?

TATSUMI: Yes, it is. But the protagonists are adults, but it’s told from the perspective of a child. It’s called “Goodbye.”

GROTH: Can you tell me what year you did this?

TATSUMI: ’Seventy-two.

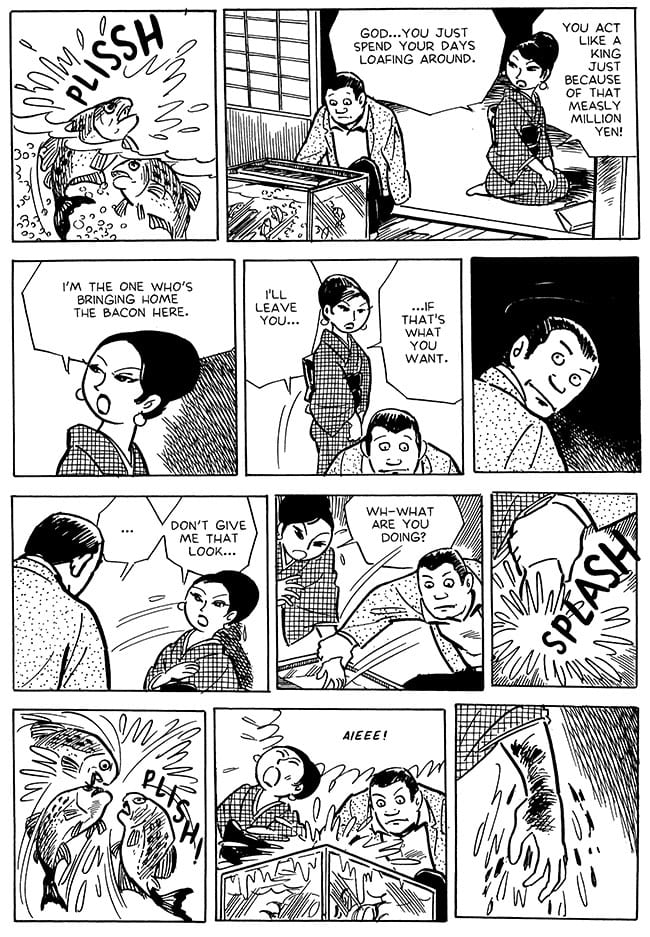

GROTH: Looking at the story, this particular work reminds me, especially this panel here, of Will Eisner … Do you know Will Eisner’s work?

TATSUMI: No … What decade was he working?

GROTH: He started around 1938, but he died last year, but he continued working until he was 84. In 1976, he started doing much more naturalistic work, similar to this. This is uncannily similar to his in terms of technique, and drawing and composition and figures.

TATSUMI: Well, there’s really only so many ways I can draw sexy. [Laughter.] But in this panel, I tried to draw it in the least vulgar way possible, because it wasn’t intended to be an erotic work.

GROTH: Right. And it isn’t.

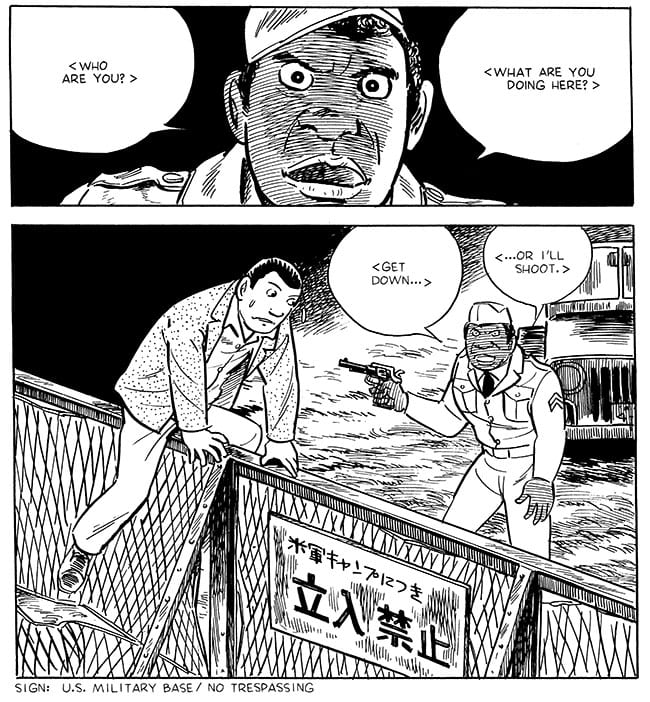

TATSUMI: So this isn’t, obviously, told from the side of the victims of the war, but this is the lover of an American soldier and this is her father.

GROTH : And there’s some tension.

TATSUMI: She’s a prostitute, and he’s coming to get money from her. Almost like, yes, almost like pimping her. So her father’s a huge burden on her, and she really wants to disassociate herself from her own family. And so here, she’s seen partying with the American soldiers, riding in the jeep. And she’s ridiculing all the Japanese men.

GROTH: Right, right.

TATSUMI: So, her father is completely powerless. He has to come to her for money. It’s not really that he’s pimping her out, but he’s dependent on her, and that’s part of the reason that she despises Japanese men, because like her father, at the time, all Japanese men were quite powerless.

GROTH: Is this true to your experience or understanding?

TATSUMI: Yes. I was only a child, but looking at the men around me in my neighborhood, they were completely powerless to say anything. They basically just had to watch silently, as women were going with American soldiers, because they were desperate even to find food. So there was nothing that they could say or do.

So, to finally sever ties with her father, she seduces him.

GROTH: [Whistles.]

TATSUMI: So then he finally leaves, after he’s slept with her. So you know, it’s unknown what’s going to happen to the father, but he clearly cannot return to his daughter. And he’s, in this panel, calling himself an animal, a beast.

GROTH: When you were in the postwar period, reconstruction, you were going to school, I presume? When did you acquire your interest in drawing, and specifically drawing comics and telling stories?

TATSUMI: Since grade school, I always did really poorly in art classes, and high school was as far as I had in formal education, but since grade school I had fun. I had very bad grades in art classes. And you really had to be rich to be able to go to college at the time. About half of my classmates dropped out after junior high school and started working. The only reason that I was able to attend high school was because I made my own tuition by submitting comics to newspapers and magazines for cash prizes. So when I was in junior high school, I wasn’t very good at drawing. But my older brother, who’s two years older than I am, was really good at drawing. My brother had to go to an abacus school. That was sort of required by the educational system.

GROTH: What is an abacus school?

TATSUMI: Just where you learn to use an abacus.

GROTH: Oh.

TATSUMI: But it was after school, specifically, to learn how to use the abacus.

GROTH: I see.

TATSUMI: And so my brother would be at the abacus school, but he would just be drawing comics during class. All of his classmates loved his drawings. And that’s when he started to have an interest in drawing. So at around that time, my brother submitted what was called a postcard comic to a magazine. And he won a prize that was this very shiny medal, and so that inspired me to start submitting my own works.

GROTH: A postcard comic is exactly what the term implies? A comic the size of a postcard?

TATSUMI: Yes. He would send in the postcard that would have the comic on it. There would be four or eight panels on a post card.

GROTH: I see. And when you were making cartoons and comics for cash prizes, would you have been 14, 15 years old?

TATSUMI: I was in seventh grade when I started submitting those.

GROTH: So you would have been 12 years old?

TATSUMI: Twelve. So many magazines and newspapers were soliciting comics at the time, because there weren’t very many comics artists working. And one time I submitted a work and I received a cash prize, and it hadn’t happened before. So suddenly I was hooked on this cash-prize idea, and from then on, I limited myself to sending works to papers and magazines that offered cash prizes.

Before the war, my father ran a laundry shop; we were living in Osaka, but because the air raids started to get so bad, we had to move to a suburb called Toyonaka. And that was around 1944. [It states in Tatsumi’s biography that his family also evacuated to Nara Prefecture in 1944.] And so my father could no longer operate a laundry business in this new suburb, that we had moved to, and he tried a lot of different businesses, but he didn’t have much of an income. So, for an eighth-grader, I was making a pretty good amount of money at the time from these comic submissions. And so I started to help support my family at that.

GROTH: Would your family have been considered working-class?

TATSUMI: Yes. I mean, they weren’t white-collar. Our family had operated a business out of our home before the war, but during the war, there were six people in my family, so anybody who could work, had to do their part.

GROTH: You had three siblings?

TATSUMI: Three siblings.

GROTH: Your mother is what we would have called a housewife?

TATSUMI: Yes.

GROTH: Now these comics you were submitting when you were 12, 13,14, 15 years old, what were they like? What were they about?

TATSUMI: They were just very ordinary, kind of benign comics. They had some humor. People would fall down and it would be funny, that kind of thing.

GROTH: Slapstick.

TATSUMI: Slapstick, yeah, basically slapstick. And I was working with single-panel, and four-panel comics. So typically, in the newspapers, they have four-panel comics, and there was one contest that was organized by the author of Sazae-San. Do you know Sazae-San?

GROTH: No.

TATSUMI: It’s the Japanese equivalent of Blondie, basically. It depicts kind of a middle-class …

GROTH: Domestic situation?

TATSUMI: A domestic situation. And it was immensely popular. Much later on it would also become a [TV] show, but at one point, the author, Machiko Haseagawa, stopped running the strip in the paper. It was published in Asahi Shimbun paper, and the readers were so upset, that she had to start publishing it again in the paper. They wouldn’t let her quit. So she ran a contest that was only for women, and it had really, really good prize money.

GROTH: So you submitted!

TATSUMI: So I submitted something under my younger sister’s name, pretending to be a housewife, when I was 12. [Laughter.]

GROTH: Did you win?

TATSUMI: Yes, I won about $600. And he —

GROTH: Your sister won.

TATSUMI: Right. [Laughs.] Yeah, she asked for her cut. [Groth laughs.] So this contest ran in this women’s magazine that was published by the Asahi Shimbun [newspaper] Machiko Hasegawa, the author of Sanzae-San, wrote her criticism of the winning cartoons. She said that for a housewife author, this work that I wrote was unique. [Laughter.] It had something to do with — I can’t quite remember, but something about a drunk husband coming home and a wife getting angry at him. It was, in a way, a work of social criticism, and that was the first time I had drawn a comic that was critical in that way.

GROTH: Was it written from a woman’s point of view?

TATSUMI: Yes, right, I mean it was a woman’s magazine. I think it was called House Asahi or something.

GROTH: Was this domestic strip like Blondie as bad as Blondie?

TATSUMI: No, its not that bad, you know, the punch line is usually kind of a common one. It’s a comedy of errors sort of thing, but while Blondie focuses on the relationship between wife and husband, Sanzae-san depicts a strange and complex family structure, so there’s small children, a husband and wife, and grandparents involved. As a depiction of the family, its quite sophisticated and interesting, at least, so that’s why it was a big hit with families.

GROTH: And you did this submission of a sort of social criticism when you were 12?

TATSUMI: I was in eighth grade, so I was 12 or 13 maybe.

GROTH: My son is 12. [Laughter.]

TATSUMI: Is he making money for you yet?

GROTH: No, but I’m going to talk to him about this when I get home. [Laughter.]

TATSUMI: I feel for sorry for your son. [Laughter.]

GROTH: It occurs to me you had an enormous responsibility thrust on you at a very young age. Did you feel that your childhood was abbreviated?

TATSUMI: I don’t really feel that my childhood was abbreviated. I think that I played like any other child during that time. But we didn’t have a lot of forms of entertainment. Of course, we didn’t have a TV, and my family didn’t even have a radio at that time, and so what my friends and I did was to try and entertain ourselves in ways that didn’t cost any money. So we would play baseball, but of course, our ball would be made out of cloth, and our gloves were sewn by our mothers, and our bats would just be a two-by-four or a piece of wood we found in the street. But there was never a lack of space, because there was a lot of —

GROTH: The fields were bombed out?

TATSUMI: — bombed out [laughter] fields.

Yomiuri Shimbun used to run a magazine that was for boys called the Shonen Giants. Or Tokyo Giants. So one time, I submitted a comic to this magazine, Shonen Giants, something like, The Boy’s Giants [referring to a baseball team] and I won a nice leather baseball glove. But it was so embarrassing to bring it out to show my friends, because we were all playing with cloth gloves, that I never even had a chance to use it. I just kept it at home. I couldn’t bring it up.

GROTH: Because you didn’t want to be seen as too affluent.

TATSUMI: Right.

GROTH: Obviously I’ve been disabused of this here, but I thought your first published work was Children’s Island in 1952. Where does that work actually stand in your career?

TATSUMI: High school starts at ninth grade —

GROTH: Yes, so you’d be about 14 —

TATSUMI: — In 10th grade. So my second year in high school was when I created that work, Children’s Island. But it took a year for that to be published, so it came out when I was in my third year of my high school. But before that, when I was in ninth grade … I’m getting confused. Third year of junior high school would be …

GROTH: Well, we don’t have three years in junior, but that would probably be the ninth grade.

TATSUMI: When I was in ninth grade, this time I submitted the work to Mainichi Shimbun. Shimbun is “newspaper.” Manichi is “daily.” And they were running a special editorial, specifically for summer vacation about … the title was something like “Genius Comics Children.” It was about kids who were interested in comics. So I submitted a work, and they were interested in me, and one day this limousine with a flag on it pulls up to the front of my dilapidated house, and my mother thinks I’m being taken away to the police station. I was whisked away back to the newspaper offices, and we conducted interviews like this [interview]. This ties into the first time I met Osamu Tezuka. I was being interviewed, and the reporter asked me whose works I liked to read, and at the time I was reading a lot of works by Osamu Tezuka, and I said, “Boy, I really like Tezuka’s work.”

And the reporter said, “Oh, you like Tezuka, too.” And I felt that the reporter had this sort of re-recognition of the popularity of Tezuka in the Kansai area at the time.

GROTH: Kansai area?

TATSUMI: Kansai and Kanto. The Kansai area includes Kobe, Osaka and Kyoto, so it’s the western area, and Kanto is the eastern area, which includes Tokyo. And so the reporter told me that he actually knew Tezuka, and he asked me if I would like to meet him. And I said of course, he’s like a god to me. And that’s how I got to meet him for the first time.

GROTH: And you would have been about 15, 16 at the time?

TATSUMI: Fourteen, 15, I think.

GROTH: So at that age, you were recognizing the names of cartoonists, and following them that closely.

TATSUMI: There were other authors that I liked, but Tezuka at that time was overwhelmingly popular. And all of my friends really loved Tezuka’s works, and some of my friends had his books. But while Tezuka was working with stories, kind of longer works, I was still working with these four-panel comics. But I found out through the reporter that Tezuka was my neighbor; he only lived about 15 minutes away from my house. So starting in about 10th grade, I started to bring him my panel comics to have him critique my work. So I was bringing him all of these strips. He seemed slightly exasperated. I don’t know if maybe they just weren’t any good. He suggested that from now on, comic artists are going to need to make longer works. “So why don’t you try your hand at creating a story, a longer piece?”

So when I was in high school, I started to create short stories that were maybe 30 to 50 pages long. And of course that was in school and I had to go to class and everything. So it would take me about three months to come up with a 30-page piece. I would then bring those to Tezuka, and he would critique them, and I would rewrite them sometimes. But those works I never submitted; I kept them to myself. So in the second year of high school — that actually would be 11th grade, I created a longer work, about 96 pages, and around that time, Tezuka’s name had spread to Tokyo, and so he was becoming popular in the Kanto area as well. And then because I started to have publishers in that area, I had to move from Osaka to Tokyo.

GROTH: That was probably a greater industrial area with more commerce.

TATSUMI: Yes, they were completely different. Osaka was sort of known more for business, but compared to Tokyo, it lacked a sort of cultural —

GROTH: It wasn’t as cosmopolitan?

TATSUMI: Cosmopolitan, right. But also the publishing industry was much more centered in Tokyo. There were almost no publishing companies in Osaka at the time. And if there were, they were sort of specialized businesses that only pressed small numbers of books. But one area of publishing that did thrive in the Osaka and the Kansai area was the rental comics market. That started in Kobe, and by this time, it had spread to about 15,000 rental bookstores nationwide. But these were not very sophisticated publishers. There might have been a person who was running a vegetable stand, and suddenly they started publishing rental comic books. So that was the degree of sophistication. And many of the comic artists who were writing comics for these rental books, were former sign painters, who painted the boards for films or kamishibai. There was a thing in Japan where there were traveling candy sellers. And if you bought candy, they would tell you a story. And the way that the story was told was that there would be a frame like this, maybe a wooden frame, and you would have panels inside it. So he would show a picture, and the man would narrate a little bit, and then pull that one out, and then he would show the picture underneath. So the story would be on this side, right.

GROTH: And he would read it on that side.

TATSUMI: And he would read it on that side, and the story would progress like that. So people who ran that business, selling candy and telling stories, also turned into comic artists.

GROTH: Good comic artists?

TATSUMI: The stories that were told in this kamishibai thing tended to be violent and more explicit than the kind of stories that were… It was a low genre, basically. They would be horror stories or samurai stories. And they would be more violent, more explicit and somewhat more vulgar than the type of comics that you would find in Tokyo. So it definitely had its own flavor.

OK, now it’s coming together. So this 96-page work that I did, this first longer piece that I drew, that was the Children’s Island.

GROTH: Ah, it all comes together.

TATSUMI: With that work, I had to send it to Tezuka, because he was no longer in Osaka. So Tezuka critiqued it for me, sent it back to me, and then I sent it to this other cartoonist named Noboru Oshiro, and he passed the work on to a publisher in Tokyo, Ysuru Shobo. And that was how Children’s Island came to be published in 1952.

GROTH: I see. And what kind of story was it?

TATSUMI: It was about these children who were living on an abandoned island, and they make do to make their lives as normal as possible with the materials that they had, kind of like Lord of the Flies. But a complete children’s comic.

GROTH: Not as vicious as Lord of the Flies. Were Tezuka’s criticism of your work useful and productive? Was he a good critic?

TATSUMI: I‘m sorry. The Children’s Island, I didn’t send to Tezuka. I sent it to Oshiro. The only works that Tezuka critiqued of mine were the short panel stories. And his critiques were not that useful. It was, you know, this is good, this is not good. Since they were really short four-panel works, I wouldn’t rewrite them. If he said it was no good, then I would just come up with a new one. But Tezuka’s works were very useful to me, much more than his criticisms.

GROTH: Useful in the sense of understanding the mechanics of comics?

TATSUMI: I mean, certainly I was influenced by his drawing style, but more than that, what was most useful or influential to me was the fact that he seemed to be depicting a world that had never been depicted through comics before. So it was radically new to me.

GROTH: And that inspired you to do the same?

TATSUMI: I never thought that I could create a new world through my art, or that I could create a world like Tezuka’s. But it was more the possibility that comics have that his works made me realize, that you could do this kind of thing.

GROTH: Many American cartoonists had that kind of epiphany, where a single work allows them to see the possibilities of comics.

TATSUMI: I wasn’t interested in following in Tezuka’s footsteps, but I wanted to create a world of my own. But with my first work, this Children’s Island, was definitely influenced, strongly influenced in style by both Tezuka and Oshiro.

GROTH: When you say you wanted to create a world of your own, do you mean that you wanted to be an original, not to imitate anybody?

TATSUMI: Yes. So I didn’t want to make a work that would fall, you know, within Tezuka’s world. The world that I could create, perhaps it wouldn’t be as expansive as Tezuka’s world. But even if it was small, I wanted it to be my own.

FUNNY INTERLUDE

GROTH: [Distracted] There are way too many Americans here. What the fuck is this? There’s this endless string of old ladies. It’s like my worst nightmare. [Laughter.]

TATSUMI: We could go downstairs, unless they’re all going downstairs, and try to call Peggy and tell her that we’re …

GROTH: The restaurant’s right on the other side of the hotel. Do you want to have lunch?

TATSUMI: Yeah.

GROTH: Peggy would manage. You call it.

TRANSLATOR TARO NETTLETON: [Laughs.] He says he’s used to this kind of scene, because women traveling in groups is very popular in Japan. In fact, they’re everywhere you go.

GROTH: These are not the best conditions to do an interview in. This is weird.

BACK TO THE INTERVIEW

GROTH: We just moved to a restaurant, so we shall continue apace. I wanted to ask you if you considered Tezuka a mentor.

TATSUMI: I don’t know that he would have considered me his student, but I definitely considered him my mentor. So yes, I mean, he critiqued my works, I definitely thought of him as my mentor.

GROTH: Did you stay in touch with him over the years?

TATSUMI: There was about a five- or six-year period after he moved to Tokyo, when we didn’t have any contact. I moved to Tokyo myself about three years after Tezuka. And I was at a party that was thrown by a publisher, and I heard Tezuka’s voice getting closer and closer, but I got nervous and ran away from him. And part of the reason that I ran is that Tezuka had become an enormous figure since he had moved to Tokyo. He was not the same person that I was visiting in Osaka, but I also knew that the work that I was making at that time — I was creating violent works, which I knew was exactly the kind of work that Tezuka detested.

GROTH: I see.

TATSUMI: So I didn’t know how I would greet him or interact with him, if I had seen him.

GROTH: Was this the work known as gekiga? Or was it something else?

TATSUMI: Yes, this was already gekiga. At this time, Tezuka knew that there was this new genre of comics called gekiga coming out. And although he hadn’t read it, he asked his assistant apprentice, if he had read this gekiga work, and whether or not it was any good, and his assistant said yes, it’s wonderful. And Tezuka got so mad that he kicked him down a flight of stairs.

GROTH: [Laughs.]

TATSUMI: This was written in a biography by the assistant. [Tatsumi revises this story later in the interview.]

GROTH: Wow. How would you describe your relationship with him over the years? Did you become friends, or was it purely professional?

TATSUMI: After two or three years had passed, after I had run away from him at the party, Tezuka was starting to become less busy, and, I think he also felt … He started to realize that his own work was, in some ways, becoming more like gekiga style. And so he would call me every once in a while. But I couldn’t call him, because he has managers and assistants, and there was no way I could reach him directly. But every once in a while, he would call me, and we would talk. I definitely wouldn’t say that we were friends, because he’s older than I am, he’s my senior. But, I felt, at some point, that we were rivals in a way. I didn’t really talk to him about our works, really. But there were points when he worked on several autobiographies, and I would speak to him when he was working on those, to talk about our past.

GROTH: Did you continue to admire Tezuka’s work?

TATSUMI: After Tezuka moved to Tokyo and he started publishing works in magazines, I felt that his works became quite boring. And actually, at that point, my colleagues and I were all quite anti-Tezuka, and we were, if anything, determined to sort of take him down. I was quite disappointed in his work when he started to publish in magazines, because what I enjoyed about his works previously, when he was working with his paperbacks that were book-length works, the looseness, because there was more space, and it was also more playful. And as soon as he started to have to publish in much shorter stories — maybe it became three and eight pages, eight pages at the most with these magazine stories — there were more panels in each page, so the page would become very cluttered. And there was no flow between the panels. So I became quite disappointed in his work at that point.

Yesterday, I sat on a panel with five other authors and we discussed the difference between graphic novels and serialized works. This was basically the same idea about him, that I was interested in Tezuka’s graphic novels. But as soon as he started to publish these in a serialized format, I felt that they had turned into comics.

GROTH: So you felt that the reduction in space constipated his storytelling?

TATSUMI: It was claustrophobic.

GROTH: Yes, right, right, to the great detriment of his cartooning skills. Would that be accurate?

TATSUMI: At this time too, he was working with assistants. And I could tell, looking at his work, that it barely had any of his own —

GROTH: Line drawing?

TATSUMI: — line drawing in it. So there’s no way that I could positively evaluate a work like that.

GROTH: Yes. What did you think of Buddha, which is, I think, one of Tezuka’s later works, one he did near the end of his life?

TATSUMI: I’ve only really read it in pieces, so I can’t really say, but from what I’ve seen, you definitely get a window into Tezuka’s religious outlook. But I myself am not religious or Buddhist, and I think that it would be considered one of Tezuka’s major works, but at the same time, I think, as a work, at points, it’s quite boring. And in a way, I feel that the world he created is not a very Tezuka-like world. Buddha is already out in the States. I’m not going to say any more but — [laughs].

GROTH: I should probably preface this by saying I’m not an expert in Japanese comics, so some of my assumptions might be wrong, but apart from the drawing, it seems to me that your aesthetic sensibilities are antithetical. Tezuka’s seems light, frivolous, more commercial, whereas yours has an existential dimension that I don’t see in much of what I’m familiar with in Tezuka.

TATSUMI: I think that it makes perfect sense that you would see our works as being antithetical. Actually, that pleases me that you would see it that way. In filmic terms, Tezuka’s work is a Hollywood work, and while Tezuka’s greatest theme is love and humanity, my work focuses really on the other side of …

GROTH: The lack of love, the lack of humanity. [Laughter.] But, yes, much as I admire his cartooning, it does seem like Tezuka is more of a Spielberg, whereas you are more of an Ozu.

TATSUMI: Well, I like to watch Hollywood films for entertainment, but as far as what I found influential, it was mostly French and Italian films.

GROTH: Italian neorealist films, like Roberto Rossellini and —

TATSUMI: I don’t really remember the names of the directors, but I haven’t seen too many neorealist films. I’m not that familiar with Ozu’s work, either. I tend to like works by unknown directors.

GROTH: Come to think of it, Ozu is not a good analogy; Masaki Kobayashi would be closer to the mark. Do you know his work? He did a film called Sepukku.

TATSUMI: I’m not sure if I saw Seppuku, but I like Kurosawa’s work.

GROTH: Like High and Low, the period in the … Well, do you like both his samurai and his contemporary drama?

TATSUMI: I don’t really like his later works that much.

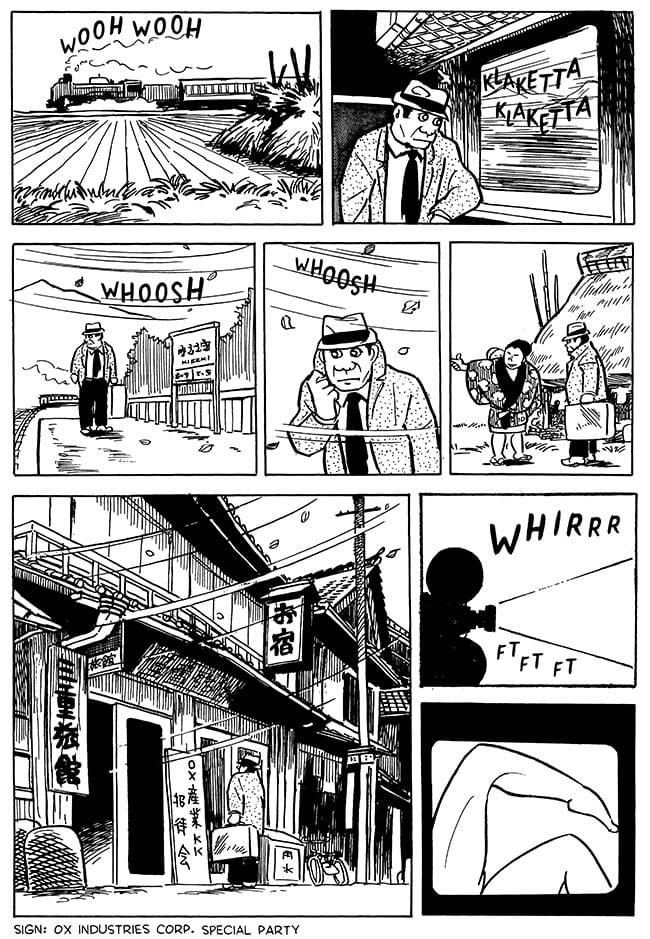

GROTH: You were a manga publisher in the ’50s, so naturally, I want to know how that came about. Did that come after you moved to Tokyo? And what kind of manga did you publish? Gekiga, or Tezuka’s kind, or some other kind?

TATSUMI: After I moved to Tokyo, I was essentially out of work. So I started my own publishing company out of necessity, primarily so I could continue publishing my own work. As I said before, a person who was running a vegetable stand could start a publishing company, so it didn’t require very much capital, and it so happened that at the time I had a friend who moved out from Tokyo who had just sold his house, so he was willing to put up the kind of start-up costs for a publishing company. I started a publishing company to continue to publish my works for the rental comic-book industry. But eventually, there weren’t any comic-book rental stores, so obviously, there was no distribution route left for me to use. Then I started to publish books that would be sold at regular retailers.

Maybe I didn’t touch on this, but the rental-books industry and the regular publishing industry had completely different systems set up. Different distributors. So I started to work with one of the major sales distributors, for publishing works in Tokyo, which also distributed all the mainstream publications. That meant I was publishing in larger numbers, but it also required more capital investment on my part. As they were publishing for mainstream distribution routes, and publishing in larger quantities, I could no longer afford to run the publishing business just by selling my own works. That’s when I started to ask other authors to contribute works. I would offer up collections of works by popular authors, other work that they had published in magazines. But this also meant because they were popular authors that I had to pay them quite a large sum of money for their works, so I went further and further into debt. I published books for about seven years. I went further and further into debt, and I was really at a point where I could not continue to run the business any more, but it was right around that time that the major comics magazines started to solicit work from me, like Shonen magazine and big comics. I think that in some ways those weeklies had seen the books that I was publishing and had evaluated them positively. So in the seven years, I published about 200 paperbacks, and of those, maybe 30 were my own works. And the rest were probably by about 20 different authors.

GROTH: The work of your own that you initially published for the rental market, was that gekiga?

TATSUMI: Yes, yes.

GROTH: Was that well received at the time?

TATSUMI: Well, the popularity of gekiga really declined along with the popularity of the rental comic-book business. So in those seven years that I was publishing, which mainly took part after the rental industry had started to collapse, most of the works I had published were not in the gekiga style.

GROTH: That you drew yourself?

TATSUMI: So now, my works were in the Gekiga style, but the majority of the works I published were by other authors, and so they encompassed works for kids that would be published in these weekly magazines for boys; there were also girls’ comics. So the majority of works were not gekiga, but my own work was.

GROTH: Did you publish work that you yourself weren’t fond of?

TATSUMI: Yes.

GROTH: How did you feel about having to do that?

TATSUMI: It was just a part of business, really. If I published the work that would sell, then that would make it easier on me financially. It was just business. But I think at the time, in general, my passion for comics had somewhat lessened.

GROTH: Why do you think your passion for comics diminished at the time?

TATSUMI: Because I felt that gekiga, and the rental comic-book industry, was being inextricably tied, so that I felt that meant that was the demise of gekiga as well. I felt that gekiga could only be articulated through longer works, through book-length works. I was afraid that was the end of gekiga.

GROTH: Your passion must have been resuscitated at some point not long after that.

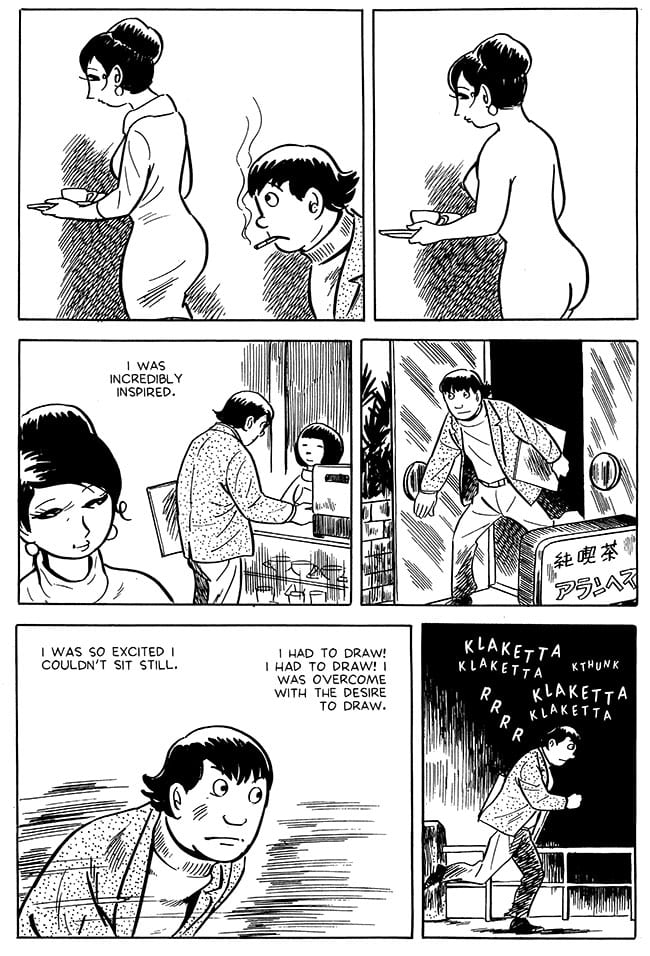

TATSUMI: Around this time, when my passion for comics started lessening, about a year or two before I stopped publishing altogether, I was approached by a third-rate comic magazine that published erotic works. And while the pay was very small, and it was a third-rate magazine, I was able to do pretty much what I wanted, there was some freedom with what kind of work I could submit. And, although it was a third-rate magazine, the magazine had a very good editor, who had a very good understanding of comics. It was in this magazine that I published the eight-page stories that are collected in The Push Man.

GROTH: And what year would that have been?

TATSUMI: Nineteen-sixty-nine.

GROTH: That’s quite far from the ’50s, when you were a publisher.

TATSUMI: I was involved in publishing in the ’60s; I stopped publishing in ’71. I was publishing [my comics] in this third-rate magazine while I was still publishing. So around ’69.

GROTH: The information that I had was that you were a publisher in the ’50s. I must’ve found this on the Internet, so it’s suspect. I just want to get this straight.

TATSUMI: It was probably in the ’50s when I started drawing gekiga style. Nineteen-fifty-seven was the beginning of the book gekiga. So next year is the 50th anniversary. [Laughs.] And your magazine is on the 30th.

GROTH: Yes it is. I also wanted to know why gekiga was so much more popular in the rental market. Was it a class distinction? Was it a class issue?

TATSUMI: It wasn’t so much about the class of the consumers, but more about the structure of the business. Because the rental comic books were published at a much smaller scale. That meant that, combined with the fact that there were so many authors and so few editors, the works would sort of pass by the editors to the publishing stage with relatively little censorship or inspection. They would barely even read the work, and it would go straight to publishing, which meant that in terms of content, you could make and create whatever you wanted. That’s why they were able to write comics that were addressing people of their own age, rather than writing for children. And that would probably not have been possible in the Tokyo market, where they were more mainstream publications.

GROTH: I see, I see. So it’s regional to some extent.

TATSUMI: Yeah. But also the business structure was completely different.

GROTH: But if they proved popular, wouldn’t commercial publishers jump on that, like piranha on raw meat?

TATSUMI: Right.

GROTH: As they are wont to do?

TATSUMI: It was immensely so with the rental comic-book scene. There were, at the height of this industry, 30,000 comics-rental stores nationwide in Japan. But although the publishers and editors of the mainstream magazines liked gekiga, and knew it was popular, the content was still too violent for them to carry in their own publications.

I have a correction to make. Tezuka did not kick his assistant down the stairs.

GROTH: [Laughs.] Wait a minute, I liked that story.

TATSUMI: He got so mad that he fell down a flight of stairs, because he was so excited and angry.

GROTH: The earlier story is better.

TATSUMI: Yeah, I know it is. [Laughter.] For Tezuka, his own work is the pinnacle of comic-making, so the fact that any other work could be good, according to his assistant, just infuriated him — that any other work could be considered good was infuriating.

GROTH: Tezuka had a healthy ego. [Laughter.] Do you know if Tezuka kicked anyone down the flight of stairs, ever? [Laughter.]

So, the commercial publishers were simply skittish over the content of gekiga.

TATSUMI: There was some sense that this gekiga rental-comics thing would not last forever. That may have been part of the reason why the mainstream publishers wouldn’t have been involved either — because they assumed it would be a short-term sale.

GROTH: You started gekiga in 1957. There’s a missing six years between 1957 and 1963 when you started publishing. What did you do in that time?

TATSUMI: I was creating works primarily for the rental-books industry, in those six years. And I was publishing through this one publisher called Henomaru Publisher, and the president of this publishing company had aspirations to move to Tokyo. Masumi Kuoda brought the idea of publishing a collection of shorter works up to me, and so the publisher thought maybe this could lead to something else, primarily publishing a magazine, a monthly magazine in Tokyo. So he took this idea, and he started to run this collection of shorter works, which was then this book entitled Shadow, and this went on for about a decade. And it was really this format of the collection that became wildly popular at the time. And while I and my colleagues believed that gekiga was most suited to book-length works, and I certainly created book-length works at the time, it was these collections that were the most popular. And that’s really what spread gekiga style. These collected volumes were about 128 pages long, and they would come out each month, and at the height of their popularity there were hundreds of these collections coming out each month.

GROTH: And what inspired you to change direction from more commercial work, to work of a more intense and personal nature?

TATSUMI: I had seven colleagues, with whom I moved to Tokyo from Osaka. And we had a discussion about how we could promote our work, and at this time I was the only person doing this gekiga, and so one of my colleagues asked, “Could we all use this term gekiga, to kind of label our works? And that way we could promote and sell our work better when we go to Tokyo.” And so that was the decision to use the phrase. Actually, in terms of content, even before they started using this phrase gekiga, they were already working in that direction. And the name basically was adopted or used, because there was a need to distinguish the comics that I and my colleagues were working on from those comics that were meant for children. It created a category that helped guide how to shelve them in these rental bookstores. Although my own works were not that violent, some of my colleagues’ works were quite violent. So people started to feel that they shouldn’t be shelved with other comics that are for kids.

GROTH: What year did you move to Tokyo?

TATSUMI: Nineteen-fifty-seven.

GROTH: Was there a point at which you recognized that the medium was a serious medium of expression? Or was it an evolutionary part of your thought process?

TATSUMI: Two years prior to starting to do this gekiga, as an experiment, I created a longer piece that was drawn very roughly. And I was sure that the editors would turn it down, so I went, luckily, on a day when the editor wasn’t there, and I was sure that later on, I would hear that they couldn’t publish it. But, to my surprise, it went straight through, and it was published, and in fact it did quite well. I even heard from my colleagues that they really liked the piece, and that they felt that it expressed something new. It was at that point that I felt confident in this kind of new direction I was taking, as a more expressive kind of form.

GROTH: Was the content of this longer piece substantially different from what you had done previously?

TATSUMI: It wasn’t entirely different from my previous work. The previous genre I was working in was mainly detective stories, thrillers, that kind of thing. And with this experimental book-length work, I was dealing with everyday events, very familiar events, kind of everyday occurrences. Maybe, you know, a child would suddenly be involved in some sort of incident. But they were everyday occurrences. And since no one else was doing that kind of work at the time, I was sure that it would fail, but ...

GROTH: Am I correct in inferring that comics were dominated by essentially children’s fare at the time?

TATSUMI: Yes.

GROTH: So this would be a radical departure from that?

TATSUMI: Well, yes, it was very different from the kind of mainstream comics. And the kind of content that my colleagues and I were creating was only possible in the rental-comics genre. And yes, the main difference was that we were addressing an audience of our own age. But I found out later, that many of our readers were laborers, workers who had recently moved to Tokyo from more rural areas, and found whatever jobs they could find. And also I heard — we couldn’t really research who were reading our works — but afterwards I found out that there were also a lot of prostitutes reading our works. [Laughs.]

GROTH: Was that a big market?

TATSUMI: Not yet. I would get some feedback when the distributors came to pick up the books from the publishers. They would tell them what kind of people were renting out the books. So I did have some indication of the fact that the readership was increasing in age.

It was in October of 1955 that I published my first self-conscious gekiga work, which was called “The Black Blizzard.”

GROTH: Now, between ’57, when you were in Tokyo, and 1969, when, I understand, that the stories in Push Man originally appeared —

TATSUMI: That’s correct, yeah.

GROTH: Were you doing longer stories, between ’57 and ’69? And then you had to start doing shorter stories, which appeared in a magazine called Gekiga Young, which was a young men’s magazine? Is that correct? I just want to make sure I get my facts straight.

TATSUMI: What was the name of it?

GROTH: Gekiga Young.

TATSUMI: Yes, almost all the works in The Push Man were published first in Gekiga Young. And I started to write these shorter pieces for magazines. Basically the rental book business collapsed. And then, I had to start writing for monthly and weekly magazines. That meant that I had to write these shorter pieces like the ones that are in Push Man. The ones that I wrote for this Gekiga Young, the pay was pretty poor, and the conditions were not that good. But, it was the first time that I found an editor that I could work with at the magazine. And so I would talk with him about what kind of themes I wanted to explore. And it was the first time I was engaged in that kind of a situation where I could discuss the work I was doing with an editor, and to have that be published.

GROTH: Your stories are so personal, they’re such personal expressions, that I can’t imagine an editor could do much to mold them one way or the other. I’d like to ask you why your vision is so despairing of humanity, which seems a constant in the two books that Drawn & Quarterly has published so far. Could you elaborate upon your perception of humanity as shown through the prism of your artistic sensibility?

TATSUMI: Uh, yes, definitely. The works are completely a reflection of the kind of anger and the pain, the desire to escape that I felt at the time. And for me personally, to try to express that within eight pages, which is quite short, was quite a struggle for me.

GROTH: Did you feel constrained by the requirements of eight pages?

TATSUMI: Yes, I found it quite claustrophobic. I think I touched on this before, but, when Tezuka moved to Tokyo and started working for magazines, I felt that his work had become really cluttered and claustrophobic. And I realized that I was going through the same process, and it was then that I understood what Tezuka was going through. That meant that there had to be more panels on a page, so it was very claustrophobic. But even beyond that, with Tezuka’s work, I just started to feel bored by them, even beyond or before this sort of technical analysis, I just found it boring. And so I was very conscious that the short-story format was very easy to become boring, to become stale, unless you composed the short story really, really well.

GROTH: One of your consistent techniques is for the men in your stories to be passive, to rarely speak. They drift silently through your stories, whereas the women are veritable chatterboxes. I’d like to know why you use that technique as consistently as you do. What are the aesthetic reasons behind that?

TATSUMI In part it was strategic, because Gekiga Young was an adult magazine, with erotic themes, sexual themes. All of the other stories in the magazine, and especially the ones toward the front of the magazine, were longer pieces — the authors got 24 pages that were relatively easier to work with. They were all sexual content, and so my strategy was to create the opposite of what was being depicted in those works. In those works, it was always the men who were the aggressors, the women were passive, and the men would dominate over the women. So to do the opposite, I thought, would create interest in the readership. At the same time, the narratives that were depicted in these other people’s stories, didn’t ring true to me.

I thought that men are not always stronger than women, and men can be weak and vulnerable and passive. But in terms of the men being silent, I think that that is a very perceptive point that you make. I’m really glad that you noticed that, because actually, the way that happened, in these discussions with this editor that I liked, at the time, I was still making works where I was relying on the speech balloon to explain the situation in the stories. Because the pieces were already short and cluttered, my editor suggested that I take out most of the speech bubbles, and that getting rid of those would not take away from the story in any way. That way you could see the image more clearly, and he thought that would be a more effective way for me to work. That was how I got to the silent character, by getting rid of the speech balloons.

GROTH: Now, was the magazine essentially pornography?

TATSUMI: Yeah.

GROTH: So in a way you were writing and drawing these stories as an antidote?

TATSUMI: Right.

GROTH: The women in the stories are almost always depicted as opportunists or parasites, and I was wondering why you made that decision, or if you even agree with my description. [Laughs.]

TATSUMI: Really? Are the women parasites? [Laughter.] [Looking at his wife.] No, it’s partly to do with my personal experience that I can’t really express right now. [Laughter.]

GROTH: [Turning to her] Mrs. Tatsumi, it might be time to interview you. [Laughter.]

TATSUMI: Umm, it’s hard for me to speak in general terms, about, you know, the way I depict women. Because Push Man collects about 20 stories, and I’ve written about a thousand … And I think that I have depicted strong men in other works, but certainly during that period, I think I did have some anxiety and fear of women.

This is a little bit off the topic and I apologize. But, my works obviously didn’t fit in very well within this magazine that was essentially a pornographic comics magazine.

GROTH: Right, that was my next question.

TATSUMI: So at a certain point, the editor was … well, the magazine wanted to stop publishing my series within the magazine. And so the editor was told about this decision, and this editor, who I liked a lot, said “The only reason that I work at this magazine, which I find boring, essentially, is because Tatsumi’s work is printed in it.” And so actually, when my work was dropped from the magazine, the editor quit the company, and moved back home to Nagoya.

GROTH: In protest.

TATSUMI: The works that are collected in The Push Man essentially killed this editor’s career. Unfortunately. [Laughs.]

GROTH: Was the editor a man or a woman?

TATSUMI: He’s a man. He was quite young at the time, and when The Push Man came out through D&Q, I tried to find him, because I thought he would be really excited about it, but I haven’t been able to find him.

GROTH: When the editor quit in protest, did the magazine relent and continue to publish your work or were you out?

TATSUMI: When the editor was told that they were dropping me, the editor said that well then, I really have serious doubts about the conscience of this magazine, and I’m quitting. And he quit, and the serial was dropped. Or the serial was dropped and he quit. That was that.

GROTH: It’s my experience that people buy pornography to read fantasy. And the last thing in the world they want to read are grim existential protests against modern life. So why in the world did they let you do that in the first place?

TATSUMI: I don’t think that the publishers would have felt that opposed to it, because I was quite conscious about the kind of magazine that it was. And so, I was very aware of what I could get away with, and to stay within those boundaries. I do include sex scenes, for example, in my works, to sort of appease the [publishers].

GROTH: Would you have done even harsher stories if you didn’t have these restrictions?

TATSUMI: I’m really not sure.

GROTH: That’d be brutal.

TATSUMI: It’s hard to say, it’s hard to speculate, because if they were any more tragic or devastating, they wouldn’t have been published. I was very aware that I was walking a really fine line. It would have certainly been much easier for me to create erotic stories. I mean, I would have had more pages to work with, as well. But I wasn’t really interested in making that kind of work.

GROTH: One of the motifs, or at least, one of the reoccurring symbols I noticed in your work is the individual within a crowd. And both stories “The Push Man” and “The Burden,” as well as the story that you showed me earlier in this book, that was drawn in 1972, I think, end with the individual within a crowd. Does that image or the idea behind it have a special significance to you? In “Beloved Monkey,” the person in the very end of the story says, “The more people flock together, the more alienated they become.” Could you elaborate on that and talk about the significance of the individual in the crowd.

TATSUMI: Well you know, that’s a basic fact, that you’re much lonelier. If you’re just with one other person, it’s fine if you don’t know them. But when you’re with 10 other people that you don’t know, you feel that much lonelier. It’s the condition of urban living. When you move to the metropolis, and you don’t know where you are, and you don’t have any work, I think that that can be a very alienating experience. Furthermore, I think that, when you’re living in those conditions, you start to envy other people that are around you, you start to imagine that everyone around you is living a better life than you are. I think that that’s a basic condition of living in the city. And when you’re with just one other person, and you envy them, you can just not see them. That’s fine. But that becomes very difficult when you are living in the city.

GROTH: Is this a condition of modern life that you deplore, or that you accept simply as a part of life?

TATSUMI: No, I accept it as an inevitable part of life. I think that a crowd, a mass of strangers, is essentially frightening. When you’re walking down the street and a mass of people that you don’t recognize or don’t know come toward you, I think that’s a frightening experience. I think that the last scene of the “Beloved Monkey” story is when the traffic light changes, and you’re waiting for this mass of people to come walking towards you. I think that’s a scary experience.

GROTH: Do you see your stories as a criticism of alienation, or as simply a depiction of what is?

TATSUMI: It’s like half and half, really. I think it’s part reality and part criticism. I think, with gekiga, it’s still manga or comics, and really, criticism is an essential part of comics. I think if I just depicted reality, it would be boring. You can’t really just do one or the other.

GROTH: Do you think criticism is an essential part of art? That art is intrinsically critical of the status quo, or of life?

TATSUMI: Yes.

GROTH: OK. My next question may be a little long but: Mass production really came to the fore in the 20th century, and it was enhanced by World War II, when mass-production techniques had to crank up due to the war economy. What sociologists have referred to as the phenomenon of Mass Man was introduced after World War II, where intellectuals were concerned that individuals were going to be subsumed by mass culture. Were you acutely aware of this evolution, and did you think things were getting worse? During your lifetime or up to this point, did you feel that things were worsening in terms of alienation, lack of empathy, lack of community?

TATSUMI: In short, yes. [Laughter.]

GROTH: I feel like I‘ve failed when my questions are longer than your answers. [Laughter.]

TATSUMI: Ah, you know, I was kidding. [Laughter.] Mass production, by definition, means that the value of objects drops. Maybe that’s good in terms of the production of culture. But I do feel that, although our lives may be becoming more and more convenient, there is a lack of sympathy between people or the relationship between people is lessened by all this convenience. And, I do feel that I had a very direct experience with this. During the war, when mass production was used in our lives, basically anything metal in our house was taken away to create bullets and airplanes, so we saw this kind of evaporation of materials for the war effort. And houses were burned down, so you know, even before thinking about mass production in relation to the war, the war itself had such an incredible effect on our lives, it basically leveled Japan. That in itself had a huge effect. I accept mass production, certainly, as an inevitable part of the modernizing process, but I can’t help but feel that there is something more valuable beyond this modernization and mass production. I can’t help but look at it critically and think that there’s something more valuable than that. I mean, when you talk about mass production, you’re not talking about the production of comics, right? I said, no, I think, more to do with the kind of worldview that’s expressed in —

GROTH: No, I meant it more in the sense of the wider societal picture and your perception or involvement in it.

TATSUMI: I ask, because, you know, in Japan, this magazine Shonen Jump is the most …

GROTH: Yes, a mass magazine of comics.

TATSUMI: It prints four million copies a week, and this sort of mass production in direct relation to comic books has benefited a few corporations, but at the same time, ruined a lot of comic artists, so I can’t but think about it in relation to that, as well, in a more contemporary framework.

GROTH: Yes, right. Certainly comics are a part of mass culture. Over here they are very tiny part of it.

TATSUMI: Right.

GROTH: And certainly not our kind of comics; we don’t worry about mass production.

TATSUMI: [Laughs.] I think that’s a really great thing, that’s still small.

GROTH: Well, there are mass-produced comics over here, and they are just as bad, I assume, as yours.

TATSUMI: [Laughs.]

GROTH: Actually, I think that’s a great way to end this, on the subject of your philosophy as part of your art. tcj

Translated by Taro Nettleton; transcribed by Ben Fischer.