On Dec. 21, 2005, Robert Crumb filed suit in United States District Court, Western Division of Washington, against Amazon.com. The suit alleged that Amazon had infringed upon his copyright of his famed “Keep on Truckin’” cartoon by using it to encourage customers to continue searching when initial book searches failed. He wanted Amazon permanently enjoined from further infringements. And he wanted its profits from this one, plus compensatory damages, attorneys’ fees and costs.

The suit startled people in the comic-book world. (Presumably, it also startled Amazon, which yanked the cartoon from its website.) As far as these people knew, Crumb had lost the rights to “Keep on Truckin’” long before 2005. The source of this belief was Crumb himself. He had been strikingly clear about it. He had blamed that loss on his former lawyer, Albert Morse.

In April 1988, The Comics Journal had published a 70-page “definitive” interview of Crumb, conducted by its editor Gary Groth. In that interview, Crumb described a lawsuit 15 years earlier, which had ended with another federal judge declaring “Keep on Truckin’” in the public domain. Partly, Crumb had said, the decision had come about because he had defied Morse - whom he described in passing as a “twisted dude” and “asshole” by refusing to testify against a publisher, whose use of the cartoon on a business card without a copyright notice had potentially dropped the cartoon into the public domain. And partly the decision had been due to Morse being “so tactless and rude” that he had antagonized the judge. Even though Morse had told him a fortune was at stake, Crumb said, he had refused to appeal. “That was kind of the end of my relationship with him,” he told Groth. “Actually, he stopped practicing law after the whole thing was over.”

This interview, in which Crumb also blamed Morse for subsequent trouble he had with the Internal Revenue Service, was reprinted in R. Crumb, volume three of The Comics Journal Library, and relied upon by Patrick Rosenkranz in his comprehensive history of underground comix, Rebel Visions. The cartoonist had previously seeded interviews in the Berkeley Barb, Relix and People with these accusations, but in the Journal, he let them flower fully; and they came to define Morse for the ages.

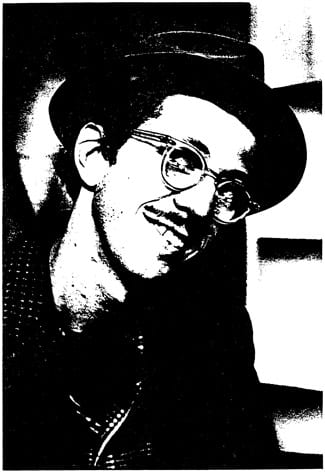

At dusk, on Tuesday, Feb. 7, 2006, 16 days after the passing of the man Robert Crumb had disparaged, about one hundred people gathered on a Sausalito houseboat for a memorial service. They talked and reminisced and chanted. His niece, a rabbi, sang a prayer of consolation and recited kaddish. One guest played Peruvian prayer bowls and another an ocarina and a naked woman a didgeridoo. Albert Morse had been a man whose outrageous humor and overflowing enthusiasms lit others’ eyes when they were asked to recall him. He had been someone who could blithely - and falsely - inform strangers that his mother had posed nude for Man Ray or that his other car was a Rolls Royce in which he was customarily chauffeured by a team of midgets. He had been someone who, if a friend’s marriage had collapsed, leaving him with two un-refundable airline tickets for a Venezuelan vacation, could step into the breach on a moment’s notice and not only accompany the dispirited husband but leave him recalling not heartbreak but visits to noteworthy Caracas cat houses and the delighted children who flocked to them on the street because Morse could pull scarves from their ears. He was, they said, the friend they would miss the most. “Anytime you saw him,” they said, “it was ‘Oh my God, Albert is here!’”

He was also a man frequently riddled by self-doubt and lacerated by despair. He was abstemious when it came to drink or recreational drugs. (Grapefruit juice became his bar beverage of choice, and at a time when, within his social and professional circles, they were more common than after-dinner mints, he may have never smoked a joint.) But he was a glutton when it came to food or other pleasures of the flesh. He lived modestly in some respects, but in others, indulged himself, Nero-like. He represented many of the major cartoonists of his time, breaking new ground on their behalf, but walked away from his law practice without glancing back. He authored, within three years, two books that were distinctive and compelling and influential, but did not do another in his last 30 years. And over his earthly run, he fashioned a life that was among the most alluringly off-kilter as any in post-1950s America. During a period when the competition for such styling sometimes seemed Olympian, he stood like a Watts Tower in a crabgrass field.

Everyone at the service had received a paper mask on which a photograph of his face had been reproduced and a candle which could be inserted at the nose and, when lit, illuminated the night. The guests could see themselves surrounded with flickering, distorted, partial images of Morse that they could carry in their memories against the erosions of time.