Love it or hate it—and some people certainly hate it—Scott McCloud’s 500-page, five-years-in-the-making art-fantasy The Sculptor has drawn widespread mainstream attention, with write-ups in major metropolitan papers from The New York Times to the L.A. Times to The Guardian. A film adaptation is in the works. Since the book’s early-February publication, McCloud, author of Understanding Comics and the indie superhero series Zot!, has been on a non-stop, massive worldwide publicity tour, a rare luxury for modern authors. With the initial U.S. tour wrapped up and the first leg of a European tour underway, McCloud is set to spend a busy summer hopping back and forth between overseas appearances and North American conventions, including MoCCA, TCAF, and Comic-Con.

But amid all the hubbub and the virtual ink spilled over the book, little has been said about its ending. That isn’t unusual in a spoiler-averse pop-culture environment. But The Sculptor’s conclusion is easily its most controversial and difficult element. The central storyline is a sometimes breathless, sometimes meandering portrait of David Smith, a frustrated, obsessive young artist who makes a bargain with Death: David has 200 days to live, but during that time, he’ll have the ability to sculpt any substance with his hands and mind, giving him the freedom to quickly and easily create whatever he wants with the time he has left. Seeing this magical ability as a shortcut around his frustrations with his work, he takes the deal, but when he winds up in a relationship with a bipolar Jewish actor named Meg, he winds up with many reasons to regret it. This interview (made entirely out of spoilers, so consider yourself warned) deals closely with the ending of the book: What went into it, what McCloud would have done differently, and why David’s final work of art isn’t necessarily meant as a masterpiece, a victory, a permanent statement, the summary of a life, or anything else it may initially appear to be.

TASHA ROBINSON: You’ve said in many interviews that your process for this book involved creating a complete rough copy, then revising it over and over. Did the ending of the book change significantly in revisions?

SCOTT MCCLOUD: This is substantially what I started with. The ending changed slightly, in small structural ways. I kept playing with the pacing and some of the smaller details. But the ending might have changed the least. A lot of the revision process was trying to earn my ending. And the ending is one of the reasons the story kept tugging at me over time. I felt if done right, that would give the book its reason for existing.

What specifically about it drew you so much?

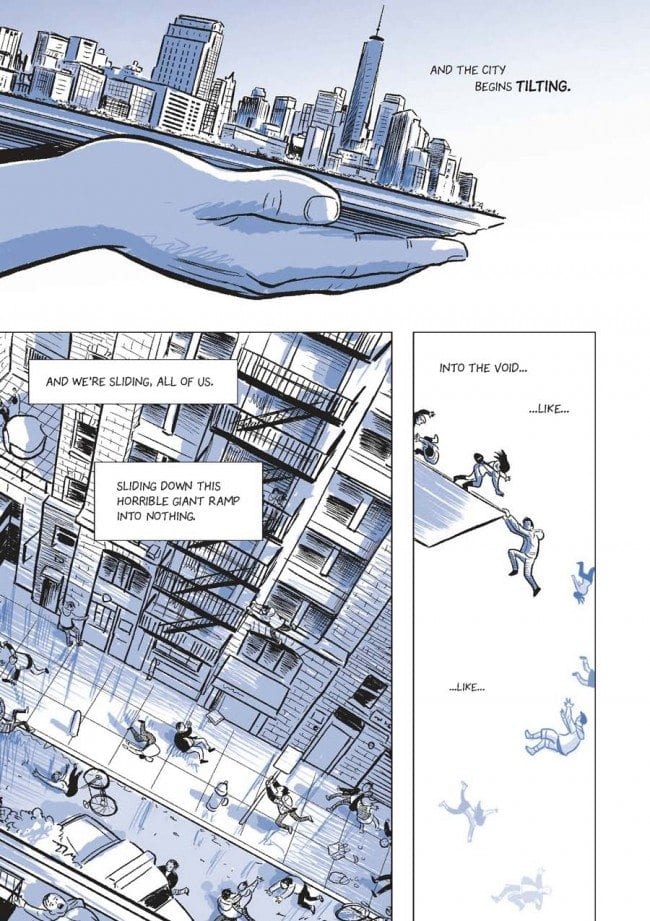

Well, I liked the monumental aspect of it. Of adding something to the New York skyline. In early drafts, toward the beginning of the book, David is talking about the things he’s yearning to do. He talks about feeling helpless at the base of these huge skyscrapers in Manhattan, and feeling like they were these works of art created by invisible hands in this meaningless, authorless process of money, politics, and Darwinian social mechanisms. And that was calling forward to the way it was going to end, with something of his rising above the skyline. But over time, I realized the book was much more about his terror of being forgotten, and that’s why that scene becomes a dream he confides to his friend, in which the city is tilting and everyone is falling off. Because ultimately, that was more on point.

And because the ending is not really about a triumph, of David’s rising above obscurity, or creating some masterpiece. I don’t think the story presents any opinion one way or another about the quality of the work. [Laughter.] In fact, I think the ending completely bypasses that, the whole idea of aesthetic work. Instead, it just becomes about this shout into the void, and also about keeping a promise to Meg. So now I think that first scene, where he talks about the dream of everyone falling off a tilted ramp of a city, I think that links up much better with the ending. And I think the entire book points to that. It’s more thoroughly about that one pounding priority in his head, to find some way of being remembered.

In terms of “earning the ending,” do you mean in terms of making the characters real enough to create that sense of emotion, or other elements?

I think in terms of making sure that all the scenes leading up to it are part of the same architectural structure. A lot of it just has to do with staying on point. When we talk about the construction of the characters and their relationship, that to me would be necessary to earn any ending. [Laughter.] That’s just necessary, you know? That’s an essential part of the writing that I had to tackle. But to earn this specific ending, specific things needed to be attended to. And I think chief among them was my coming to grips with what the story was actually about. It’s that old saying that readers should only really fully understand what the story was about after they’ve finished it. I’m sure that’s not universally true, but to me it sounds like sound advice. And I think it’s also true for the writer, as well. In some ways, you need to read your story to know what it’s about so you can write it. And that’s what makes rewriting necessary.

So ultimately, for you, is the story about David’s struggle to come to terms with all the issues around what he makes, what it means to him, and how other people relate to it?

Ultimately, I’m trying to show why I see the struggle against being forgotten as futile, but also why I see that futility as beautiful. And I suppose this relates in some ways back to my feelings about art, and the feeling that all art is gloriously useless. [Laughter.] It serves no particular utilitarian function. If it has any other function, then it’s not art. So I admire a character who not only continues to struggle in the face of futility, but even does so when he fully understands the depth of that futility. Which I think David does by the end. He actually gets it. Thanks to his relationship, he finally understands that particular truth, that it doesn’t matter what he does. It’s all going to be washed away by time. Everyone gets washed away by time, even the artists we think of as immune to it now. You push the timeframe forward far enough, we’re all going to be extinguished eventually. He understands that, and he continues to struggle. That, to me, is what’s beautiful.

It feels awfully grim and cynical, though. You give him an apotheosis where he looks at Meg and sees a continuity, a circle of life that he’s become part of. He realizes even if he can’t be immortal through his art, he’ll be immortal through their child. And then you prove him wrong.

David doesn’t make the break, though. Fate steps in. You can blame the author for that, obviously. But I don’t see it as cynical. He decided he was willing to settle for Plan B, and then it was taken away from him, and he had to go back to Plan A. But what he actually chooses to make, I suppose, has very little to do with that at all. He’s keeping a promise. You have to go back to the conversation they have when she comes back to let him know she’s pregnant. She establishes certain conditions, and asks him to make a promise he thinks he can’t make in the moment. But his final act is to fulfill that promise that he didn’t make.

The opening prologue has David telling Meg, “I got one,” and her saying, “Whisper it in my ear.” Then the story begins, and it feels like a story he’s telling her. For the longest time, it feels like this could all just be a 25th Hour-style fantasy he’s spinning, laying out this dramatic alternate world for the two of them. But close to the end, you reveal that the prologue was a different conversation altogether, and he’s just sharing a secret. Did you mean for that moment to feel like an escape hatch for readers?

No! No, actually, I like that! But no, it’s just one of those little surprises, one of those threads you accidentally create as you’re trying to tell one story, it spins some other stories in the mind of the reader. That’s kind of cool, but it was unintentional. Although I did anticipate some people think this entire story is being experienced by David in the split-second before he dies. That all 500 pages are happening in that moment.

The secret he tells Meg in that moment is meant to be something she’ll carry on after he’s gone. And again, you make a point of drawing a connection with the future, then severing it.

This is the continuity most people settle for. Almost everyone who sets out on the path to make art will see their work mostly forgotten by everyone but their family. That’s the usual story. And whatever yearning they have to leave something behind usually defaults to family and friends, to their relationships. And there’s usually some comfort in that, because you’re stepping back into the parade of evolution, of how our species works. The way we become part of something greater than ourselves just by being part of the human race. I think art is a way we step outside of that race, and start to do things that aren’t geared toward survival and reproduction. But there’s comfort in stepping back in. Because we hope to create something beyond ourselves, and yet most people can’t. So this is partially a story about that.

You know, the first chapter of the book is called The Other David Smith. For a while, I considered calling the last chapter of the book the same thing, because there’s another David Smith. But you could almost say the book is about the many other David Smiths, the ones he sees in that old printed phone book. In some ways, that’s who I’m talking about.

You come back to the image of that phone book during his flashback just before death, which underlines the importance of what seems like a random image when it first comes up.

[Laughter.] Well, as an artist, I had to find a lot of images for those pages. But that one seemed important enough to me to include as one of his recent memories.

Those flashback pages are powerful because we’ve seen or heard about so many of those moments. The readers have become a part of that continuity, of what he considers the significant times of his life. What was your process like in selecting all those images?

It was very dull and methodical. [Laughter.] Just making lists, seeing what he’d mentioned, then trying to fill in the blanks. There was nothing exciting about drafting it. But they weren’t superfluous. When his life passes before his eyes, I’m hoping that scene uses that past material in a way that’s more transformational. I tried very hard to make sure that from beginning to end, this story stayed wrapped around this idea of being remembered. What he receives in this flood of memories from his own life is a kind of existential counter-argument to the idea of the memories we leave for others, beyond our lives. I was trying to show in that explosion, in the depth and breadth of those memories and experiences, why they should be seen as carrying an equal or even greater weight than whatever we think we might be able to instill in the memories of others.

David and Meg’s deaths have impact because you take the time early in the book to establish that there’s no afterlife, nothing waiting for them but the void. Was that to keep people from romanticizing their deaths, from imagining them as being reunited somewhere?

For me, that’s just my particular orientation. I’m a secular person, I’m an atheist. And so I’m using fiction and fantasy as a lever from which to postulate a world I believe does exist, in which we have our lives and nothing else. So driving that home—like you say, one of the advantages from a narrative viewpoint is that it more clearly delineates the stakes. If David’s just trying to come up with something for the living to remember while he goes off and parties with the angels, the whole thing seems a lot more trivial. You’re correct that I’m trying hard not to romanticize David’s death. When visualized in a single panel, it’s anything but romantic. We see his brains splattered on the sidewalk. Meg’s death is different. I allowed myself a kind of peculiar visual callback to her entrance into the story, with the crowd ring. I didn’t have a specific purpose there. I lived in New York, and that’s what people do when there’s an accident. When something happens on the street, that ring forms. But I let it sit there and have a near- supernatural resonance, because I thought that was just interesting. It was interesting and unresolved.

I talk about being on point, or being on theme, but I also understand that if you take that to extremes, you just have a blueprint of a story. And I didn’t want that. And so when mysteries like that creep in, I tried to welcome them. Things that didn’t further any particular theme or idea, but just sat there, blinking at me. They pose questions that can never be answered, and I just liked that.

As you say, David’s death is portrayed graphically, but hers is more idealized. She was hit by a car, but her body isn’t broken, there’s no blood.

There’s a little on the sidewalk, but yeah. I went back and forth on that one, and if I’d had more time, I maybe would have given more thought to the makeup department. But there are just so many moving gears in this thing. Yeah, I think maybe I should have curbed my impulses to romanticize that. I’m not really sure. This may just be one of those cases where I ran out of time, where I didn’t sit down and have a little conference call with myself about how to stage that, exactly.

Meg’s death has such a familiar resonance for comics. In mainstream superhero comics, there’s such an awareness and dubiousness at this point, any time you have a woman dying in a story solely to give a man a big emotional moment. No matter how well it’s contextualized or written, it feels at this point like it’s playing to a trope.

That was on my radar from the beginning. The only problem is, I was writing a story about a man who kept losing people he loved. And the loss of people he loved was the entryway into the simple fact that everybody dies. And the story has to come back to square one before it’s done. There’s really no avoiding it. I couldn’t see a way at all the story made any sense at all without that ending. I still don’t. He has to face down death in its purest form. He’s given the opportunity to turn away from that toward the end of the story. All his musings about the continuity of life are his opportunity to turn away from it, as we all do.

I mean, that’s what we do! Family and heritage and our connections, these are ways we can basically forget about death. What’s that old saying, that we watch our children on the path ahead of us so we don’t see death coming up behind us? And that would be untrue to what the story is ultimately about, if he wasn’t forced to confront it in its purest form. There needed to be that break. He couldn’t have that comfort, he couldn’t have that loophole from which to escape the simple fact that we all die and we’re all forgotten. It’s the second death, which even an atheist might not necessarily grasp that within their lifetime. Art is almost the kind of religious loophole for atheists like me. [Laughter.] We’re not going to go to heaven, but maybe we can make things that go to heaven. And get judged by some vague, unspecified art-verdict machine. It’s ridiculous, but we let ourselves believe this. And I couldn’t give David that out.

There’s an idealized streak around women in your work. With Meg here and Jenny in Zot!, they’re both removed figures with a kind of exaggerated beautiful melancholy that takes them out of the world.

Zot is far more romanticized than Jenny.

Sure, but in a different way. He’s a superhero from another world, an actual comic-book character from a more rarefied and idealized place. He’s removed from our world because he doesn’t come from it.

Yeah, she’s drawn to his world, she wants to go someplace simpler. Though I don’t know that that’s romanticizing her. It’s just a natural human instinct to want to go to a better place.

I mean how she’s drawn emotionally.

Oh. Absolutely. When I look back at Zot!, the whole thing’s a little weepy for my tastes now. I’ve always been sentimental. I just don’t think I kept it in check as well back then. I think it did get a little better as it went. If you go from the early color issues to the black-and-white stuff, you can see some of the sentiment starting to slide off a little. But it never went away completely. Clearly it hasn’t gone away completely. This is a very sentimental book on some level. It just has a much harsher background. I mean, look at what we’ve been talking about. [Laughter.]

Setting Meg up as an avatar for family, love, life, connectivity, continuity, art, inspiration, and hope, all at once, and then killing her, certainly does feel like a conscious step away from sentiment. Or idealism.

I don’t see it that way. I think to me, as a story point, it was a level of harshness that I felt I didn’t have a choice on. I felt it necessary to the story, but it was harsh enough for me personally that the fact I may have made it more picturesque, more romanticized, a little more Pietà than if she’d been upside-down in a woodchipper. Romanticizing her death may have been me thinking, “If I’m going to stab my audience, at least I’m stabbing them in the heart instead of in the liver.” Really, it was just me saying, “Enough. I don’t have to show her head split open.” But that’s just because I don’t necessarily have much tolerance for violence.

The art in the book changes around Meg’s death. Holding up the book and looking at it from the side, you can see where the pages suddenly turn darker, with the black extending to the edges of the pages. Much of the action after she dies happens at night, and underground—

—and in the rain. There’s a lot of ink falling from the sky.

But the pages go black, and then as day breaks and the fog comes in, the pages go white. What was your thinking about using that kind of full-page ink saturation as part of telling the story?

I was actually kind of pissed off at myself that I was having so much trouble introducing enough spot-black. I didn’t feel like I was anchoring the story enough. But when he brings her down to the old tunnels, I thought, “If I can’t get the spot-blacks right here, I should just hang up my hat and go home.” [Laughter.] So I remember when I was doing the layouts, I did those pages as almost abstract slabs of black. I was just fighting myself from the first 430 pages or whatever. It irritated me that I still hadn’t gotten the blackness right. So I tried to use it in a more integrated fashion for those pages, because the scene really seemed to demand it. Because there’s no natural lighting down there, just little flickers of light from the street above.

It’s still not good enough. The first few panels look good, and then it looks a little flat. But if it had been too light, it would have looked too angelic. He is literally at his darkest point. He’s without direction. His only paths are closed off to him. And he’s literally looking at a collapsed, old subway tunnel that goes nowhere. I was certainly anxious about the idea of the rain just being delivered on cue. Which is one of the reasons why they talked about the rain, how the rain was something he wanted. He didn’t like the idea of dying on a sunny day. And Meg kept telling him to not be a baby, just take whatever he’s given. So the idea that David wished for the rain, I liked that, that the universe was perverse enough to give him what he wanted, but not in the way he wanted it.

And then of course it goes light toward the end because I have the problem that he’s creating his work in a public place, where everybody would be able to see it all the time. So I brought the rain and fog in to give him a kind of unveiling. Otherwise, the whole last scene, people would have been walking around talking about what he was making, and telegraphing the ending. So there, also, I allowed myself a bit of a curtain-pull that hopefully seems plausible, and not too theatrical. I even had a couple of panels early on where you see skyscrapers disappearing up into the clouds, as a sort of scene-setting for later.

There’s a moment down in the old tunnels where Death-as-Harry tells David that Harry secretly committed suicide after his wife Sadie died, but wants David to know it was a mistake. The narrative gets a little tangled there—we know Harry died in war at 19, and Death came home embodied as Harry. But then he talks about Harry in the third person, and in the present tense as though he still exists, and he lays out this other death. It’s unclear where the different versions of him separate.

I guess in my mind, when Death takes Harry’s body in the war and brings him back, Death is living as a human being—fully. There’s an actual, full human being there that has full knowledge of who he is, but is nevertheless fully alive, and has all those human feelings, including a genuine relationship with Sadie. To me, it made sense that Death would not share the details of Harry’s death with David when they meet. It’s morbid, and it’s of no use to David—unless David experiences something similar, which he does. Harry is fading. We’re told he’ll fade as David’s time comes. But what’s left of him wants to communicate this information to David before his time goes.

And that’s part again of the process of David losing everybody. Even this resurrected version of a twice-dead man has to leave his life.

Exactly. Harry has to go. David has to be genuinely alone. To me, the idea that everybody dies alone makes a lot of sense. [Anya’s Ghost author] Vera Brosgol was one of my early readers of the layout, and she noticed the gunshot that takes David down, as this little distant “bang” out of the fog. And she put in her notes something along the lines of “Death is small and private, even for King Kong.” I hope I’m not misquoting her. But I think that’s true. So it has to be intimate. That part of David’s existence doesn’t have an audience. In stark and deliberate contrast with the big gesture that everybody sees out on the street, the experience of his death is somebody nobody sees but him.

(continued on next page)