In February 2008, when Rutu Modan was last interviewed for The Comics Journal (in issue #298, by esteemed comics journalist Joe Sacco), the Israeli cartoonist had just released Exit Wounds, her wildly successful first graphic novel which soon wound up on nearly every pundit’s year-end list. Swept up in a tidal wave of critical acclaim, Modan’s debut was nominated for a Quill Award and won the 2008 Eisner Award for “Best Graphic Album.” Though Modan had been involved in comics for more than a decade by that point, having started out illustrating newspaper strips in Jerusalem before briefly editing the short-lived Hebrew version of Mad magazine and then co-founding the Israeli cartoonists’ publishing collective, Actus Tragicus, Exit Wounds was a transcendent book, introducing Modan to an international audience and launching her into an entirely new orbit.

In the six years that followed, Modan published several children’s books (including her relentlessly charming debut solo effort, Maya Makes A Mess, from Art Spiegelman and Francoise Mouly’s prestigious comics-for-kids imprint, Toon Books), two impressive short strips for the New York Times (“Mixed Emotions” and “The Murder of the Terminal Patient”), an experimental work of comics journalism (“War Rabbit”), a quirky, ill-fated pilot for an animated cartoon series (“Goody Two Shoes”), and several one-off illustrations (including spots for, of all things, a physics book about anti-matter). However, despite this incredibly prolific output, the question of a second graphic novel always lurked in the background. Could she possibly top Exit Wounds?

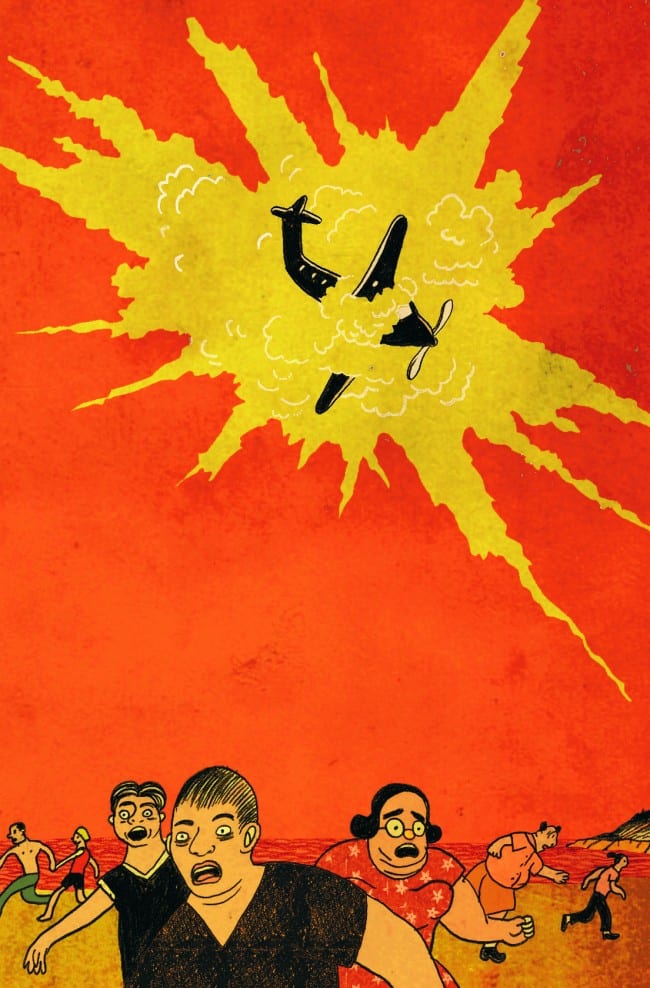

With The Property, Modan’s imminent second graphic novel from Drawn and Quarterly, the artist has put those questions to rest definitively. The Property takes the intricate ideas and themes introduced in Exit Wounds – the complicated yet unbreakable bonds of family, the impact of politics and war on individuals, the beauty and irrationality of human relationships, the harsh realities of Israeli life - and delves much deeper. The multi-generational story explores these ideas and more through the lives and relationships of several psychologically complex, extremely memorable characters, whose interwoven stories are rendered in Modan’s meticulous, richly-colored compositions.

In my conversation with Modan, conducted over Skype in April, the artist candidly discussed her background, her family, and the many influences and ideas that found their way into her new book, as well as her unique creative process.

- Marc Sobel, May 2013

“The Black Sheep”

MARC SOBEL: I was hoping you could start by giving me a little background on yourself.

RUTU MODAN: OK. Well, I was born in a hospital.

SOBEL: Well… <laughs>

MODAN: No, no. I also grew up there. It’s a hospital near Tel Aviv and inside there is a neighborhood where all the staff, the doctors and nurses, live. It was built this way by the first manager of the hospital because he wanted the doctors near, so he could call them at any hour and they would come. So there is actually a small neighborhood inside the hospital and I grew up there until I was about 11, and then we moved to Tel Aviv.

SOBEL: Both of your parents were doctors?

MODAN: Yeah, scientists and doctors. So being an artist was considered a very strange decision in my family.

SOBEL: <laughs>

MODAN: My father could never get over the fact that I didn’t become a doctor. He used to say ‘with your hands, you could be such a wonderful plastic surgeon.’ <laughs> For years, he used to say that. When I told them that I was going to art school, they started laughing. Not because they thought it was so bad, they were just surprised. It was surprising for them that art was something you could go to learn. To them, it was just something that you do in your spare time after you save lives.

SOBEL: Do you have siblings?

MODAN: Yeah, I have two sisters. The older one is a doctor. <laughs> She sacrificed herself so that my parents would be satisfied. And I have a younger sister who writes for TV. She’s also an actress. She’s actually a very big star in Israel, a celebrity.

SOBEL: Would she be known in the U.S. at all?

MODAN: I don’t think so, but in Israel she’s… Let's just say that when I go with her to buy clothes, all the sellers in the store call her by her first name because everybody knows her. So between us three, we always fight about who is the black sheep. <laughs>

SOBEL: How would you describe what your childhood was like growing up in the hospital environment?

MODAN: It was actually a very nice place because the neighborhood was surrounded by the hospital, so there were no roads and no cars. It was very small and everybody knew each other. It was like a small kibbutz, but where everyone is either a doctor or a nurse. It was a very safe environment, and very friendly.

Only when I grew up did I start to think that it was a little peculiar. I used to go visit my parents in their office and on the way I was walking through all the departments where… there are some things that a child is not supposed to see, but it was just around me so I accepted it.

For example, I remember during the Yom Kippur War, in 1973, our hospital is one of the biggest in Israel, so all the wounded soldiers from the front were sent there by helicopters and the place where the helicopters were landing was right near where we kids used to play, so we saw all these helicopters coming with the wounded soldiers. I was seven then and it was very interesting to see the helicopters. It wasn’t frightening at all. As a child, you don’t think about it. You just accept everything. You think this is life, you know?

And then there was one instance... Do you know the holiday Sukkot?

SOBEL: Yes.

MODAN: You build these little huts, and you sleep and eat in them. In Israel, the children really like this holiday, and in our neighborhood, because it was so small, all the kids were raised together. So it was during the war and we were building our sukkah until a grown-up came and saw that we had actually used wood that was from coffins. These were the coffins that brought back the dead bodies of soldiers. We just found it and thought, ‘oh, this is great’ but, of course, they took it away from us. <laughs>

SOBEL: Wow.

MODAN: I think growing up in that environment influenced my work later on.

SOBEL: In what ways?

MODAN: In how I use black humor. I like black humor and there is always some dead person in the story. I’m not the first author to write about death, but it’s a theme that’s really central in my work.

“I Failed Really Hard”

SOBEL: In other interviews, you’ve talked about how even though you didn’t necessarily see many comics as a kid, you were drawing stories with pictures from a very young age.

MODAN: Well, I probably saw some comics from time to time. I don’t think I invented it. But I remember when I was really little, I would draw on the x-ray papers in the hospital. Those were the sheets that we were drawing on. <laughs>

SOBEL: Can you describe the kind of drawings you were doing as a kid?

MODAN: What’s interesting is that it was always connected to the story. It was very natural for me to express myself that way. I also have this notebook with drawings and stories I did when I was six or seven, some even using thought bubbles and word balloons.

SOBEL: Were you sharing these with your family or friends?

MODAN: Yeah, my parents really liked them. They showed them around to their friends and were laughing, and I was hurt, because I felt they didn’t take my stories seriously enough. They didn’t think drawing was something I would do for a profession, but I was really encouraged to do it. I told you before that they were surprised when I told them I was going to art school, but they didn’t try to stop me. The main thing about education was to find your profession and stick to it because it’s your life, like medicine was their life. So, if it’s drawing, ok, as long as you’re doing it seriously.

SOBEL: How did your work evolve as you got older?

MODAN: In a way, I’m more connected to my childhood than to my teens because when I became a teenager, I stopped drawing for a few years because I was so self-conscious. I didn’t think I was good enough. Besides, I was more interested in boys than drawing comics, and… I was also more interested in being conventional, which I couldn’t, but I tried very hard. <laughs> Only after my Army service did I start drawing again.

SOBEL: So you did serve in the military.

MODAN: Sort of. Everybody in Israel has to go into the Army service; it’s not something you just volunteer for. But there are too many people, so there are all kinds of jobs that you can do which are not really military. I didn’t want to go, but at that time, it was unthinkable not to do it. It was in the ‘80s, and not to go to the Army was like not doing your fair share. It was a very contrarian move.

So I went to kind of a social service. Basically I went to live in a small town near the border and we worked with youth and children. We did cultural projects instead of real Army service, but it was still Army service.

SOBEL: You did that for two years?

MODAN: Actually, I did it for three years, because for doing social service instead of the regular military I had to do an extra year, but I didn't care. I was very idealistic and wanted to change the world. Now I regret it.

SOBEL: Why do you regret it?

MODAN: I lost a year of my life when I was young and could have been having fun. Instead I was trying to do really important things and I failed really hard. <laughs> I didn’t change anything and it was a very frustrating experience.

SOBEL: So, it was after you left the Army that you started drawing again?

MODAN: During my final year in the Army I had a friend who encouraged me to go back to drawing. Then one day another boy who served with me, an immigrant from the U.S. showed me a book by Edward Gorey. This was a real culture shock. I never saw anything like it before. I had only seen one book of Tintin, and a few comics with, do you know Tex? It’s a cowboy comic.

SOBEL: Oh, right.

MODAN: When I was a child, my dentist had some Tex comics in his waiting room, but I never saw anything like the work of Edward Gorey. The drawings, the stories and his unique humor... wow! I fell in love with it immediately. So I tried to imitate him, and then I started doing comics again. But this time I knew more about what I wanted to do.

“Nobody Said It Was Going to Be Fun”

SOBEL: So was this when you first got involved with Mad magazine?

MODAN: I went to art school in Jerusalem first, and in art school there was a teacher, Michel Kishka. He came to Israel when he was eighteen, but he grew up in Belgium, so he knew a lot about comics, and he is a comics artist himself. He taught the first comics course at the Academy. There were only six students in that class and I remember the first lesson because he brought all kinds of comics, including Raw magazine. This was a real culture shock. I looked at those and said ‘wow, this is exactly what I want to do.’ I was in my third year, so I already knew that I wanted to be an illustrator, but when I saw Raw, suddenly everything fell into place. It was like ‘this is it.’

During the next semester, which was three months later, I started publishing a comics column in a local newspaper in Jerusalem.

SOBEL: Can you describe those early strips and how that opportunity came about in the first place?

MODAN: It was fun because at that time, there were almost no comics in Israel. It was the early ‘90s, and there were maybe three artists who were doing comics professionally. It was hardly even in the margins.

It was very easy to get a comics column. I had no competition. I just went to the editor of this newspaper, who was a young man, 28 or 30 and new at his job. I told him I wanted to do a comic strip, and he thought it was very cool. He didn’t know anything about comics and not so much about being an editor either, so he hired me and gave me a salary. It was a very small one, but still… <laughs>, for a student, it was amazing.

I started doing the first column, but after a while, I ran out of ideas, so I changed the subject and format and started an entirely new column for a while, and afterwards, when I got fed up with that one, I changed the format and the story again. Everything was very flexible because there was no tradition, you know? Nobody knew how it was supposed to be done. Sometimes it’s an advantage when there’s no tradition. You have more freedom and no one to tell you ‘this is how it’s done.’ You know, like, ‘if you’re doing this kind of strip, you can’t stop and suddenly change everything.’ But I would say, ‘ok, now I have an idea for a double spread so can it be this size this week?’ and if they had space that week, they’d say, ‘ok, have a double spread.’ It was very flexible.

The first strip was done in a kind of Jules Feiffer style. My mother had a book of his cartoons and I really admired his style. In my strip, each week a different little figure would tell its story, usually a funny one, with a punch line. Afterwards I did these four panel strips of macabre stories that have no logic. They were very ‘80s. It was the ‘90s, but since I was in Israel, it was like the ‘80s here. <laughs> They were kind of like Mark Beyer’s style

SOBEL: Amy and Jordan.

MODAN: Right. Then, after a while, I was doing comics about this awkward woman detective who tries to solve unreasonable mysteries. Then for a while I did these Edward Gorey-type stories with all these lines in that very Victorian style.

So I was experimenting with all kinds of styles and writing techniques, and I did that for about six or seven years. Then they changed the editor and everything stopped. Suddenly they realized that it was a stupid idea to pay someone to do comics when they could get it for free.

At that time I was already fed up with a weekly column, anyway. The week is unbearably short when you have a regular column.

SOBEL: How widely read were these strips?

MODAN: I have no idea, and I didn’t care at the time. I didn’t think about it. I was just happy to do it.

SOBEL: Were they in a national paper?

MODAN: No, it was just in Jerusalem in the beginning and inconsistently they were printed in the Tel Aviv supplement as well. Later I worked for the Tel Aviv supplement and stayed there for three years.

Parallel to this, around ’93, I started working with Etgar Keret. At the time he was publishing short stories in the newspapers. He was already quite popular, but still not the big star he became soon after that. I really liked his stories, which are very visual and full of imagination and action. So, since Tel Aviv is very small and it’s easy to get to someone if you want to, I called him and said, ‘Let’s work together.’ Luckily he liked comics, so he agreed. We started with a double-spread, or even two double-spreads if they gave us the space, and we did this twice a month or so.

SOBEL: Is this work available online, or do you ever plan to collect the material into a book?

MODAN: We did publish a book. In 1996, we collected what we thought were the best stories and put them together into a book. By then Etgar was a very successful writer, so the publisher agreed to publish this collection, even though it was common knowledge back then that comics don’t sell in Israel. I think Israel is the only country on Earth where Tintin and Superman didn’t succeed.

SOBEL: Wow.

MODAN: Yeah. Nobody wants to read about Superman or Tintin in Israel. <laughs> Or Batman. Or Mad magazine. And Etgar's and my comics were even worse from a publishing point of view, since they were in an alternative style. But the publisher accepted it because of Etgar. We collected these stories and the title Etgar gave it was Nobody Said It Was Going to Be Fun. <laughs> Actually, it did pretty well but the publisher didn’t realize it. We sold about 5,000 copies, which we thought was very good. Even now, that’s a nice number, but since the publisher sold like 50,000 of Etgar's regular books, he said, ‘see, nobody reads comics in Israel,’ and he refused to publish any more comics. <laughs>

I cannot publish this book again, though, because the drawings are from 17 years ago and I can’t stand them. <laughs> They’re embarrassing for me. The stories are still wonderful but the drawings are not. So the drawings are just sitting in boxes in my studio. Maybe when I'm 80 I’ll be able to stand them again.

SOBEL: Can you describe your job as an art teacher?

MODAN: I’m on the faculty of the Bezalel Academy of Art and Design in Jerusalem. I studied there twenty years ago and now I teach comics and illustration. It depends on each year which course. Right now I am teaching a comics course. Last year I taught a course on children’s book illustration. Usually it’s two classes of three hours each. I really like teaching. I’ve been doing it almost 19 years.

SOBEL: Wow.

MODAN: Yeah, I started two years after I graduated.

SOBEL: What are some of the lessons you try to instill in your students who are trying to get established as cartoonists?

MODAN: It’s different if I teach first or second year students versus third or fourth year students. To the younger students I mainly teach working methods, techniques, idea development, etc. In the third or fourth years, the courses are more focused and a student who chooses my course usually knows that he/she is interested in comics or illustration.

What’s most important for me to teach the students? I think to be honest and do what you like. And be curious. And don’t try to be original. All of us take from each other and stand on the shoulders of past artists. Also, it's important to open yourself to influences, but not to imitate. Or to do what is comfortable, or what you think will be commercial, or what people will like, because you won’t succeed. I tried this once when I was a young artist. To get a certain project, I tried to draw in what I thought was a commercial style. Nobody liked my style so I tried a different one, and did it badly and didn't get the job. I really think that now more than ever, people will succeed if they have something to say and they find a way to say it in an honest, interesting way.

Also, it’s very important to be professional. By that I mean that you need to understand that it’s not only your talent, but also the way you manage your career. Basically be nice to the people that you work with. Students don’t think it’s important. They think the only thing that matters is that you are talented, but I tell them that talent is only good for the first time you work with someone. Maybe during school students can make trouble and still pass if they're talented, but in the professional world, people don’t have time for that.

“The Most Important Thing in the World”

SOBEL: Can you describe what Actus Tragicus is and what role you played in founding it?

MODAN: It actually began with Mad. Mad was selling the rights to international publishers and there was an Israeli publisher that wanted to try to make comics popular in Israel so he bought the rights to publish Mad magazine in Hebrew. This publisher happened to be my Uncle, who also didn’t know much about comics, but liked Mad. He said, ‘ok, you’re doing comics, Rutu, so you could probably be an editor.’ <laughs> So he asked me if I could do it and I said, ‘why not, I’ll do it,’ but I asked Yirmi Pinkus, who’s a good friend of mine to do it with me so it would be more fun.

So we did it for a year and a half and it was a disaster. <laughs> What did I know about editing? I didn’t know anything. We had to use 75% American material from Mad, and we could only add original material to the other 25%. The problem was, what we actually wanted to do was Raw magazine and the comics we added were in that alternative style. So the people who liked Mad magazine hated all the original Israeli stuff, while the other people who liked the alternative comics hated all the Mad material. Nobody bought it and after ten issues it was closed. Then Yirmi and I decided that if doing comics meant losing money anyway, we might as well do exactly what we want.

We decided to establish a group of artists and start publishing our stories ourselves, because there was no one else to publish them. We were young and stupid. We didn’t know anything about publishing, and we didn't care. We just said, ‘ok, we’ll do it in English and sell it abroad,’ and we thought it would be so easy. We had no idea. This was before the Internet, so we didn’t know anything about the international comics market. All I knew about comics was when I went abroad and saw these beautiful comic stores, but I didn’t know anything about marketing, or even that there was a difference between mainstream comics and alternative comics. I didn’t realize that they’re totally different markets.

SOBEL: So how did Actus evolve? At what point did it develop into a big, international collective?

MODAN: Big? International? <laughs>

SOBEL: Maybe not big, relatively speaking, but…

MODAN: In the beginning, Yirmi and I didn’t think about an artist’s group. We only thought about self-publishing. But since we were going to Angoulême [in 1995], we wanted to look like a "real" publisher. We wanted to look serious, so we invited a bunch of cartoonists to Yirmi’s apartment and told them that we were going to open this independent publishing house and whoever wanted to join could join.

I especially remember this night because it was only a day or two after [Prime Minister Yitzhak] Rabin was assassinated [November 4, 1995] and the atmosphere was very tense. All everybody wanted to talk about was the assassination, not about comics. Still, we managed to convince two other artists to join us in this comics adventure: Itzik Rennert and Ephrat Beloosesky, who was a photographer who wanted to experiment in the comics medium.

Our first series were small mini-comics in black and white. Later we discovered that, with this small format, stores didn’t know where to put them. We probably thought that we were going to conquer the world of comics. <laughs> So we went to Angoulême with these four mini-comics and we hired a stand in the international area. Angoulême changed our vision. When we got there, we saw everything that was being done and it was so amazing. There were so many books and so many artists that suddenly it was even more exciting. I used to smoke back then and I think I smoked four packages of cigarettes a day during this Festival <laughs> because I was so excited.

SOBEL: Wow! <laughs>

MODAN: You know how when you’re walking a dog in the street and then suddenly it sees another dog; when they meet, the dogs immediately start to play together, because they rarely meet other dogs. We were like that. There were no comics people around [in Israel] and suddenly, to come to a place where there were so many people into comics, and so many books! So we decided we wanted to keep doing it so we could be part of this wonderful, beautiful world of comics.

We decided that we were going to publish a book every year. Then Ephrat left and two new cartoonists joined us: Batia Kolton and Mira Friedmann, and after that Actus just developed on its own. We would decide on a format, which usually depended on how much money we had, and then each one started his own comics. As the years passed, the main thing became the creative process.

SOBEL: Did you work together or separately?

MODAN: We used to meet once in a while and criticize each other’s work, which was great. After you finish a project, it’s too late. You don’t want to hear any criticism; you just want to hear that it’s wonderful and then again that it’s wonderful. <laughs> Even maybe again. <more laughs> It’s irritating to hear criticism after it’s published, because what can you do with that? It's too late to fix anything. But when you’re still working, if it’s someone whose taste and judgment you trust, it’s very helpful. It’s like working with an editor, but in comics, you don’t usually have one. We don’t have Actus anymore but I still work with Yirmi and Batia and it’s the same. They show me their work and I show them mine, and then we discuss it. They might say really bad things, and they can be really harsh sometimes, but they do it in a nice way and I trust that they’re doing it because they really want to improve my work. Every artist should have this kind of group, or at least one or two people that can work with them this way. I feel really lucky to have such friends.

SOBEL: Did you guys pay for everything yourself?

MODAN: Yeah, completely. In 1998, we decided it was time to see what was going on in America, so we went to SPX. We tried to get some funding from the Ministry of Culture for the trip, so we wrote this really nice letter explaining how comics are the most important thing in the world <laughs> and each of us got $35.

SOBEL: $35?

MODAN: $35 each. And for that, we had to go to meet the Consulate in New York and say ‘thank you’ very nicely because they gave us that $35. <laughs>

SOBEL: That’s ridiculous.

MODAN: That was the last time we tried to get support from anyone. We realized it's not worth the effort.

“That Was a One-Time Experience and Actually I Didn’t Like it”

SOBEL: You’ve mentioned that Drawn and Quarterly contacted you and commissioned Exit Wounds. Can you talk about how that played out and how that relationship evolved?

MODAN: Well, of course I knew Drawn and Quarterly for a while. I had admired their books since the ‘90s when they started their anthology with artists like Seth and Maurice Vellekoop. I actually met Chris Oliveros in 1998 at Angoulême, and I think we even had dinner together, but it wasn’t until 2004, after our Happy End book, that he contacted me and asked me to do a story for the anthology they used to have [D&Q Showcase].

SOBEL: Was there something about that story in particular that motivated Chris to get in touch?

MODAN: I think Happy End was the first time that I found a way to combine my stories with the Israeli reality. I was avoiding it for many years, not because I wasn’t interested in what was going on, but because I didn’t know how to combine the Israeli reality with the stories I wanted to tell. I didn’t want to do political stories, or comics journalism. When I tried to do it at first, it became, like… I don’t like stories that have an agenda. Well, there’s always an agenda to a story but a political agenda is different from an artistic agenda. In politics you always have to decide what side you’re on, but in stories, I like them to be more ambivalent because I think that life is more ambivalent than politics, even in Israel. So I think that story was the first time I found a way to combine the two, and probably this is why Chris was interested.

I think my stories became more sincere after that. First I did “Jamilti,” which I think was kind of a test, and not long afterwards Chris sent me an email and asked me to do a full length book. I almost fell from the chair, I was so happy. I started screaming so hard that my husband thought that something happened to our baby son. <laughs> He rushed in from the living room, yelling ‘what happened?’ I was screaming because I was happy but also because I was frightened about the fact that I had to write a novel <laughs> which I had never done. But I had to do it, you know? It was my dream for so many years.

SOBEL: Do you feel a sense of responsibility for how you portray Israel to an international audience?

MODAN: When I write a story, I try to forget the audience. It’s very dangerous to think about the audience when you write. Anyway, you cannot predict what the reader will understand from your work, and actually, it's not my business. I don’t write for anyone. No, that’s not completely true. I write for Yirmi Pinkus. I write for him because he’s my best friend and I’m interested in what he is going to say about it.

I don’t feel responsible for portraying Israel either. Mostly I just try just to be honest. I love Israel, and I also hate Israel, so everything somehow gets into the book.

One of the things I keep telling people abroad, because I’m always asked why my stories are not about politics or the war, I say that I cannot devote my comics to explaining the Israeli-Palestinian situation to Europeans or Americans because I don’t understand it myself. The only thing I can do is tell the truth from my point of view.

SOBEL: So you don’t see your work as having any kind of political agenda?

MODAN: No. The only time that I did a “political” comic was in 2009. I was living in England then, and I got a commission by a French publisher (Delcourt) who was putting together an anthology of comics journalism. At first, I said, ‘no, thank you, I’m not interested in that; I’m just interested in doing fiction.’ But then over the Christmas holiday, we went back to Israel for a vacation and it was right as the Gaza War started. I thought it was terrible. I couldn't see the logic in what was happening (as if there is ever logic to war). Then suddenly I felt that it was irresponsible not to take this project, that I could not avoid reality that much. I felt I had to take the opportunity to show the events from my point of view as an Israeli who's against the war but still sees the complexity of the situation.

Well, I am not very brave, and I was afraid to go alone to the south, where the war took place, but I knew a journalist, Igal Sarna, from the café where I usually sit. He is an old-time journalist who is always going to the most dangerous places. He’s gone to Jenin to interview some of the scariest terrorists, so I called him and said, ‘Igal, let’s do something together.’

So he took me on a tour… we couldn’t go into Gaza, but we went to the border and met with people who live there and were bombed and then we did this short, thirteen-page comics journalism story which was published in the French anthology and also in Words Without Borders. It’s called “War Rabbit” and you can read it online in English.

But that was a one-time experience and actually I didn’t like it. I liked the experiment, and I learned a lot from Igal, but in the end, I didn’t like the comic so much. I didn’t feel it was really me.

SOBEL: You’ve also done work in America for the New York Times. Can you talk about how those stories came about?

MODAN: There were two projects. One was “Mixed Emotions,” which was an illustrated blog. I was commissioned to do a story once a month, and because I work very slowly and it’s so hard for me to find a good idea for a story, I chose to do autobiographical comics and tell stories about my family. I would say those stories are about 98% true. <laughs> The best part of this project was that since it was online, people could comment. When the first story was published and I read the comments, I started to cry. It was so moving to read how people reacted to my work. Usually a comic artist is detached from the audience. You do the book and then some critics sometimes write about it, but it’s not like normal readers can respond. That was beautiful.

Then I did a serial story called “The Murder of the Terminal Patient.”

SOBEL: This was the one in The Funny Pages?

MODAN: Yes. I felt really honored because there were such great artists doing this project before me.

SOBEL: You were invited by the editors at the New York Times to do this story?

MODAN: They probably saw “Mixed Emotions” and asked me to do this project. It was fun, and also it was the first time, maybe the only time, that there was some connection with how much work I did and how much I was paid. <laughs>

(Continued)