When comics are composed as effortlessly as Raina Telgemeier’s, they are too easily dismissed. Such work is deemed simplistic, childish, or merely ‘popular.’ Telgemeier’s best-selling books such as Smile, Drama, Sisters, and Ghosts, which typically fall under the Young Adult or slice-of-life umbrella, often fall prey to such thoughtless descriptors. Telgemeier’s work routinely garners much praise but not much critical attention. In a blog post titled “11 Million Reasons to Smile,” comics scholar, Bart Beaty, notes that “the near total absence of scholarly discussion of Telgemeier and her work,” given her popular success, is “just a little bit insane”. At minimum, this article aims to correct this oversight by investigating avenues of scholarly literature that engage with Telgemeier’s work and by providing critical insights into the composition of Telgemeier’s newest work, Guts, from a formalist perspective.

When comics are composed as effortlessly as Raina Telgemeier’s, they are too easily dismissed. Such work is deemed simplistic, childish, or merely ‘popular.’ Telgemeier’s best-selling books such as Smile, Drama, Sisters, and Ghosts, which typically fall under the Young Adult or slice-of-life umbrella, often fall prey to such thoughtless descriptors. Telgemeier’s work routinely garners much praise but not much critical attention. In a blog post titled “11 Million Reasons to Smile,” comics scholar, Bart Beaty, notes that “the near total absence of scholarly discussion of Telgemeier and her work,” given her popular success, is “just a little bit insane”. At minimum, this article aims to correct this oversight by investigating avenues of scholarly literature that engage with Telgemeier’s work and by providing critical insights into the composition of Telgemeier’s newest work, Guts, from a formalist perspective.

Bart Beaty’s prediction that the lack of attention given to Telgemeier’s work will “change over time” as “[t]omorrow’s undergraduates” undertake comics criticism, is already becoming actualized (“11 Million” 2016). A cursory literature review of Telgemeier’s work shows promising new scholarly developments. Although most articles that mention Telgemeier are still overwhelmingly popular and promotional – interviews with the artist, reviews of the artist’s work, or otherwise promotional materials geared towards library and middle school book acquisitions – a proliferation of recent dissertations are engaging on a deeper level with Telgemeier’s work. These dissertations appear to be limited to the field of Education (Bender 2018), Library Studies (Bulatowicz et al. 2017), and Reading Instruction (Rogers et al. 2014; Wang et al. 2016; Ojeda-Beck et al. 2018;), but some are engaging with critical comics theory (Grice et al. 2017). A survey of these dissertations suggests that deeper engagement with Telgemeier’s work is a fairly recent occurrence and that this scholarship is still in its infancy.

Outside the realm of dissertations, in a recently published critical text entitled Autobiographical Comics (2018), Andrew J. Kunka makes note of Telgemeier’s work in two chapters, “The History of Autobiographical Comics” and “Social and Cultural Impact.” Kunka’s overarching investigation focuses on the steady increase of autobiographical comics over the past three decades and aims to understand “why autobiographical comics ha[ve] become such a worthy area of study for scholars, students, and creators”. After overviewing the history of autobiographical comics, Kunka examines the field of graphic autobiography from a generic perspective. He turns to Telgemeier’s work in a discussion of twenty-first century autobiographical comics as it regards the success of webcomics, especially those published as diary comics. According to Kunka, Smile, initially published as a web comic on Girlamatic.com, was part of this major proliferation of autobiographical comics in the twenty-first century. Naming Smile “[o]ne of the most significant autobiographies in recent years”, Kunka lists its impressive array of publishing statistics such as “175 weeks on the New York Times ‘Paperback Graphic Books’ bestseller list” and “over 1.5 million copies in print, and around 240,000 copies sold in 2015 alone”. Though Kunka asserts that such “astounding publishing success” will have “long-ranging effects on publishing decisions, comics scholarship, the cultural impact of comics in general, and autobiographical comics in particular”, he fails to address Telgemeier’s work in a scholarly capacity or question why her work has reached such overwhelming success and consequently deserves scholarly investigation outside of their genre and publication platform.

Outside the realm of dissertations, in a recently published critical text entitled Autobiographical Comics (2018), Andrew J. Kunka makes note of Telgemeier’s work in two chapters, “The History of Autobiographical Comics” and “Social and Cultural Impact.” Kunka’s overarching investigation focuses on the steady increase of autobiographical comics over the past three decades and aims to understand “why autobiographical comics ha[ve] become such a worthy area of study for scholars, students, and creators”. After overviewing the history of autobiographical comics, Kunka examines the field of graphic autobiography from a generic perspective. He turns to Telgemeier’s work in a discussion of twenty-first century autobiographical comics as it regards the success of webcomics, especially those published as diary comics. According to Kunka, Smile, initially published as a web comic on Girlamatic.com, was part of this major proliferation of autobiographical comics in the twenty-first century. Naming Smile “[o]ne of the most significant autobiographies in recent years”, Kunka lists its impressive array of publishing statistics such as “175 weeks on the New York Times ‘Paperback Graphic Books’ bestseller list” and “over 1.5 million copies in print, and around 240,000 copies sold in 2015 alone”. Though Kunka asserts that such “astounding publishing success” will have “long-ranging effects on publishing decisions, comics scholarship, the cultural impact of comics in general, and autobiographical comics in particular”, he fails to address Telgemeier’s work in a scholarly capacity or question why her work has reached such overwhelming success and consequently deserves scholarly investigation outside of their genre and publication platform.

Kunka’s later chapter regarding the social and cultural impacts of graphic autobiographies is similarly devoid of such insights. Asserting that, “graphic narratives, including autobiographical comics dealing with traumatic historical events, not only say something about a specific event, but also about how such events can be represented”, he eventually returns to Telegemeier’s work as an example of the intersectional representation of adolescence and trauma. The age of the narrator-protagonist in autobiographical comics does not seem to be a limiting factor to scholarly attention as Kunka describes several texts featuring adolescent and child narrators who do receive much scholarly attention, some of which are listed below. In response to Beaty’s aforementioned blog post, Kunka suggests that Telgemeier’s work may not have received much scholarly attention because her work “doesn't fit within a lot of the key subject areas or theoretical frameworks that Comics Studies tends to focus on”. To illustrate his point, Kunka goes on to list more thematically mature negotiations of childhood trauma in comics that detail sexual abuse: Pheobe Gloeckener’s A Child’s Life and Other Stories (1998), Debbie Drechsler’s Daddy’s Girl (1999) and Craig Thompson’s Blankets (2003). While it does seem to be a generic trend that autobiographical comics proliferate under such genres as the confessional autobiography, which is typically used to relay traumas through witness testimonies, such examples may receive excessive scholarly attention because of their ties to fields such as trauma or psychoanalytical studies. The same may be said for autobiographical comics regarding the trauma of war, or otherwise life under the rule of oppressive regimes, such as Marjane Satrapi’s Persepolis 2000, Mariam Katin’s We are On Our Own (2006), and Riad Sattouf’s The Arab of the Future (2014).

Although Kunka explains that “Telgemeier does subtly handle some challenging topics in Smile,” such as interracial relationships, puberty, topics of disability, and homosexuality, he fails to address the fact that on a formal level, Telgemeier’s work offers as much to the understanding of autobiographical comic composition as the aforementioned texts; moreover, the formal composition of her autobiographical texts may lend itself both to Telgemeier’s popularity and to the proliferation of the autobiographical genre in the twenty-first century.

Although Kunka explains that “Telgemeier does subtly handle some challenging topics in Smile,” such as interracial relationships, puberty, topics of disability, and homosexuality, he fails to address the fact that on a formal level, Telgemeier’s work offers as much to the understanding of autobiographical comic composition as the aforementioned texts; moreover, the formal composition of her autobiographical texts may lend itself both to Telgemeier’s popularity and to the proliferation of the autobiographical genre in the twenty-first century.

Critical Analysis:

Telgemeier’s latest graphic novel, Guts, not only tells the story of the awkward transition into puberty and the gut-wrenching self -consciousness that accompanies this liminal life-stage, but also demonstrates the rich compositional quality that Telgemeier’s comics have to offer. Telgemeier weaves complex story-telling practices across her latest text, and her burgeoning canon, by using comics’ formal properties to problematization the meaning of words and demonstrate Raina’s negotiation of verbal stigma. Some of these formal properties include visual compositional techniques such as shot-reverse-shots and juxtaposition; word-play; typographical manipulations; gutters, gaps, and polyptychs; wordlessness; and iconographic recodification.

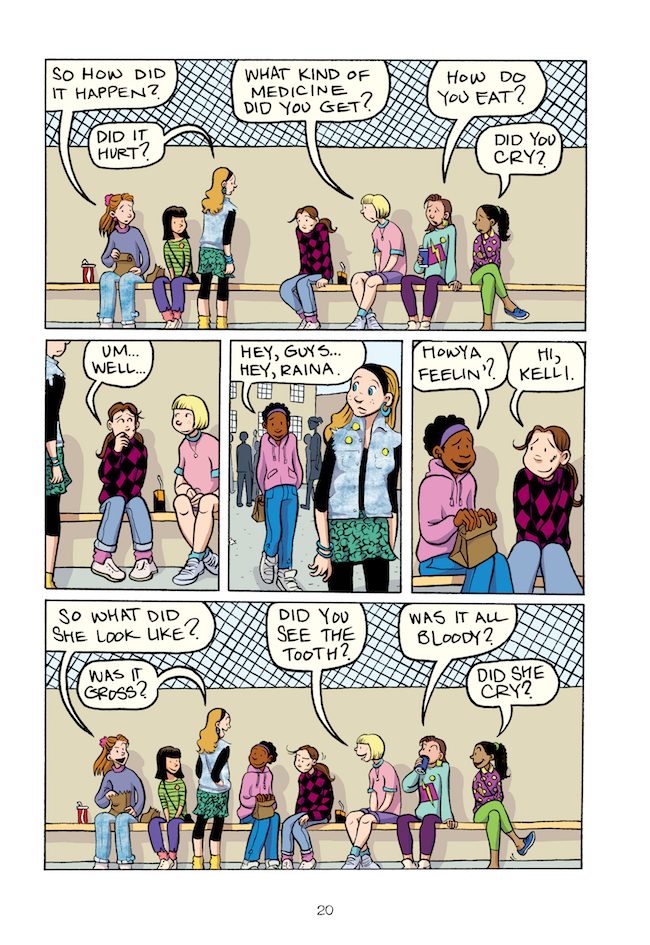

Though Guts focuses on Raina’s struggle with anxiety, the careful reader will notice that Telgemeier previously introduced this issue in her Eisner Award-winning book, Smile. After confiding to her mother that she feels like throwing up (Smile 21), Telgemeier shows the gap between Raina and her mother’s understanding of the circumstances causing her nausea. While her mother attributes Raina’s nausea to poor eating due to emergency dental work, Raina’s expression of doubt and sadness in the subsequent shot-reverse-shot sequence reveals to the reader, but not her mother, that this is not the real reason for her queasiness. Instead, the reason for Raina’s nausea is shown on the previous page through a compositional structure that both isolates Raina from her social group while simultaneously making her the focus of her friend’s intrusive inquiries. Telgemeier positions Raina at the center of two elongated panels on the first and last tier with a sizable gap between her and the rest of her classmates to emphasize Raina’s isolation and her classmates’ scrutiny. Telgemeier illustrates Raina’s social anxiety and her inability to communicate this anxiety through such subtle compositional techniques within and across panels; Telgemeier deftly link these two scenes through a two-page layout and a shot-reverse-shot sequence that also serves to impede the characters’ understanding.

Raina’s doubtful facial expression in Smile communicates to the reader what her verbalization cannot, an experience that she does not quite have the words for. Similarly, in Guts, Raina’s younger sister, Amara, asks, “Is Raina sick, mom?”, to which her mother responds, “Yes” (Guts 24). A caption on the opposite page, however, problematizes the word “sick” as an accurate description of Raina’s experience: “‘Sick’ isn’t quite the right word for it./ But something was definitely wrong” (Guts 25). The previous unspoken depiction of social anxiety in Smile becomes Telgemeier’s focus in Guts. Attempting to describe her inner landscape throughout Guts, Telgemeier shows the reader how difficult, frightening, and visceral words can be through their recursive (re)negotiation in the comics medium. Telgemeier also demonstrates that such continual re-negotiation is necessary to challenge verbal stigma associated with anxiety. Through her verbal-visual composition, Telgemeier reminds the reader that words are malleable entities that can be shaped by ourselves as much as they can be shaped by others.

The very title of Telgemeier’s work, “Guts,” is just one example of this verbal malleability and the varying positive or negative connotations that can be associated with words. “Guts” may indicate one’s physical digestive system, but also the sensation associated with a certainty in the pit of one’s stomach, or “gut-feeling.” “Spilling your guts” has a connotation of regurgitation (a prevalent theme of the book and an anxiety-trigger for Raina), but this phrase also connotes the figurative act of sharing or confessing your inner secrets to another through oral communication. The word “guts” can also be associated with a visceral and overpowering feeling of hatred for another, as in the phrase, “I hate your guts,” or conversely an expression of admiration for a courageous act or person, such as the commendations “That takes guts!” or “You’ve got guts!” Throughout Guts, Telgemeier invokes each of these connotations demonstrating the changeability associated with the core of our being.

Telgemeier deftly outlines the complex implications of words by manipulating them in a visual-verbal form to depict their emptiness, their internal and external oppression, their escapable formulation, and their malleability as they take on diverse visual incarnations throughout her work. Throughout Guts, adult caregivers offer Raina several truisms and platitudes, which are shown by Telgemeier to be devoid of meaning or guidance for navigating stressful situations. When Raina returns to class early from recess due to her classmate Michelle’s verbal teasing, Mr. Abrams, Raina’s fifth grade teacher, recites the quote, “Be kind, for everyone you meet is fighting a hard battle” (Guts 93). However, Telgemeier demonstrates that these words are initially ineffectual for Raina’s predicament, who translates Mr. Abrams’ “teacher-speak” (Guts 94) to: “If I’m nice to you, maybe you won’t be so mean to me” (Guts 94). This quote does not indicate how Raina is supposed to communicate with Michelle to achieve this act of kindness and leaves her skeptical of receiving any kindness in return for her efforts. Later, another platitude, “Treat others as you wish to be treated” (Guts 143), is shown to be equally ineffectual as Raina’s attempt to participate in a class activity leaves her socially ostracized and verbally stigmatized through such peer reactions as: “What’s your deal?”, “Do you have an eating disorder??!”, and “Nah, she’s just a weirdo” (Guts 146). Mr. Abram’s platitude is not demonstrated towards Raina, thus the negative verbalizations she faces become externally oppressive without much recourse.

Telgemeier deftly outlines the complex implications of words by manipulating them in a visual-verbal form to depict their emptiness, their internal and external oppression, their escapable formulation, and their malleability as they take on diverse visual incarnations throughout her work. Throughout Guts, adult caregivers offer Raina several truisms and platitudes, which are shown by Telgemeier to be devoid of meaning or guidance for navigating stressful situations. When Raina returns to class early from recess due to her classmate Michelle’s verbal teasing, Mr. Abrams, Raina’s fifth grade teacher, recites the quote, “Be kind, for everyone you meet is fighting a hard battle” (Guts 93). However, Telgemeier demonstrates that these words are initially ineffectual for Raina’s predicament, who translates Mr. Abrams’ “teacher-speak” (Guts 94) to: “If I’m nice to you, maybe you won’t be so mean to me” (Guts 94). This quote does not indicate how Raina is supposed to communicate with Michelle to achieve this act of kindness and leaves her skeptical of receiving any kindness in return for her efforts. Later, another platitude, “Treat others as you wish to be treated” (Guts 143), is shown to be equally ineffectual as Raina’s attempt to participate in a class activity leaves her socially ostracized and verbally stigmatized through such peer reactions as: “What’s your deal?”, “Do you have an eating disorder??!”, and “Nah, she’s just a weirdo” (Guts 146). Mr. Abram’s platitude is not demonstrated towards Raina, thus the negative verbalizations she faces become externally oppressive without much recourse.

In Telgemeier’s work the onslaught of stigmatic verbalizations, especially from Raina’s peer group, is physically affecting. As in the aforementioned example of anxiety coded as situational nausea in Smile, the reader transitions to Raina’s confession of nausea following a scene where Telgemeier shows Raina as socially isolated by a series of inquiries that “other” her: “Did you cry?”, “Was it gross?”, “Was it all bloody?”, “Did you see the tooth?”, and “What did she look like?” (Smile 20). These inquiries are designed to make their target feel self-conscious about their emotional and physical state. This type of socially stigmatic interaction continues in Guts through both implied and overt applications of a stigmatic identity through name-calling. Being self-conscious about her diagnosed Irritable Bowel Syndrome (IBS), Raina reacts vociferously to Michelle’s whispered accusation in class that Raina is “A poopy diaper baby” (Guts 47), an accusation Raina cannot defend herself from without alerting her peer group to the verbal stigma and precipitating her total ostracization from her peers.

Telgemeier visualizes how such stigmatic verbalizations evolve from an occasional externalized pressure to a constant internalized pressure that fuels her anxiety and oppresses her by typographically manipulating words throughout her visual narrative. Raina indicates she feels so “Babyish. / Weird./ Dumb./ Stupid” (Guts 155), all implications and fears she has picked up from the verbal stigmatization expressed by her social group. Telgemeier makes full use of the comics medium’s ability to visualize verbalizations as expressive images by manipulating their size, shape, texture, and colouration to indicate either the emotive quality associated with the words or the affective response the word has on the protagonist.

When asked to explain her experience in her own words, between Raina’s verbalized “Um…” (Guts 74) and “…I dunno” (Guts 75) three panels later, Telgemeier fills the panel space with a dizzying mass of words that represent Raina’s internalized experience of anxiety. At first, the words come out in an expanding but limited stream as if hand-printed by Raina in a variety of sizes: “Siblings, sickness, school, comics, fear of vomit, mean people, sleep, death” (Guts 74). Some of these words have negative connotations or experiences but are otherwise typically neutral words. As the sequence progresses, these words turn into swirling phrases that create a verbal vortex around Raina: “Scared of my parents dying;” “Scared of surgery;” “Scared of pooping my pants;” “Scared of getting bad grades;” “Scared of needles” (Guts 75). Several of these verbalizations signal more physical concerns, academic expectations, and some larger fears associated with mortality. These words are still depicted as hand-printed by Raina, becoming larger and larger as the vortex swirls around her. By the third panel of the sequence, the words are engorged, conveying an enormity and heft that physically oppresses Raina. Red, jagged, block letters that spell “WAR” and “PAIN,” as well as other wavy fonts that spell “DEATH” and “CHOKING” (Guts 75). Words press down on each other and ultimately compress Raina into a miniscule figure in the final panel where no words can be seen but their effects are clearly shown.

In this succinct three-panel sequence, Telgemeier visualizes the existing gulf between internalized and externalized words and the difficulty in formulating words that can adequately encapsulate one’s emotional state and experience of anxiety. Telgemeier’s visual composition elegantly reveals the reason behind this inability to verbalize the internal experience of anxiety through the following splash page polyptych (Guts 76). Telgemeier subtly splits Raina’s figure into two parts through a slim horizontal gutter that separates Raina’s head from her body, effectually indicating the disconnection that exists between Raina’s ability to mentally connect the physical sensations she is experiencing to her thoughts and emotions. Importantly, the thought bubbles emanating from Raina’s mind are pictorial and not verbal: A lightbulb, a swirl, a tear drop, exclamation and question marks indicating ideas, insights, and a sense of confusion (Guts 76). These visualizations emphasize Raina’s inability to attribute a word, category, or label to each sensation. Icons occupy her torso, including a storm cloud, lightning bolt, a pink heart, red star, blue balloon, smiley and sad faces (Guts 76). These icons indicate diverse and likely concurrent emotions that are difficult to disentangle, let alone verbalize, such as simultaneously experiencing happiness and sadness, pleasure and pain. As Telgemeier’s captions explain: “Thoughts can exist… Feelings can exist… / But words do not always exist” (Guts 76-77). In Telgemeier’s case however, images exist, which, when skillfully composed, can communicate both these feelings and their confusion.

In this succinct three-panel sequence, Telgemeier visualizes the existing gulf between internalized and externalized words and the difficulty in formulating words that can adequately encapsulate one’s emotional state and experience of anxiety. Telgemeier’s visual composition elegantly reveals the reason behind this inability to verbalize the internal experience of anxiety through the following splash page polyptych (Guts 76). Telgemeier subtly splits Raina’s figure into two parts through a slim horizontal gutter that separates Raina’s head from her body, effectually indicating the disconnection that exists between Raina’s ability to mentally connect the physical sensations she is experiencing to her thoughts and emotions. Importantly, the thought bubbles emanating from Raina’s mind are pictorial and not verbal: A lightbulb, a swirl, a tear drop, exclamation and question marks indicating ideas, insights, and a sense of confusion (Guts 76). These visualizations emphasize Raina’s inability to attribute a word, category, or label to each sensation. Icons occupy her torso, including a storm cloud, lightning bolt, a pink heart, red star, blue balloon, smiley and sad faces (Guts 76). These icons indicate diverse and likely concurrent emotions that are difficult to disentangle, let alone verbalize, such as simultaneously experiencing happiness and sadness, pleasure and pain. As Telgemeier’s captions explain: “Thoughts can exist… Feelings can exist… / But words do not always exist” (Guts 76-77). In Telgemeier’s case however, images exist, which, when skillfully composed, can communicate both these feelings and their confusion.

Telgemeier also uses the polyptych to emphasize the oppression experienced by the negative thoughts that mentally attack Raina and the ubiquity of her anxiety experience. As previously noted, the polyptych emphasizes Raina’s sense of fragmentation physically and mentally. However, it also communicates Raina’s long-term experience with anxiety as a four-tier polyptych (Guts 120), illustrating Raina’s full figure through four temporally and spatially different areas: lying in bed at bedtime; lying in a field; lying on the couch with a book; and lying in a bath (Guts 120). Raina represents herself as prostrate in this composite image, depicting the day-to-day experience of anxiety immobilizing her. However, the captions in each horizontal panel of the overall polyptych, create an active and cyclical call-and-response type of internalized dialogue that emphasizes Raina’s continual self-examination, repetitive worries, and inability to solve or answer these recurring self-posed inquires: “Was puberty to blame for my stomach aches?/ I don’t know./ Was puberty to blame for my sudden panic attacks?/ I don’t know!” (Guts 120). The repetitive wording of the phrasing emphasizes the recursive experience of her anxiety experience while depicting its fragmentary effect on Raina, which consequently prevents its verbal expression.

Telgemeier also uses the polyptych to emphasize the oppression experienced by the negative thoughts that mentally attack Raina and the ubiquity of her anxiety experience. As previously noted, the polyptych emphasizes Raina’s sense of fragmentation physically and mentally. However, it also communicates Raina’s long-term experience with anxiety as a four-tier polyptych (Guts 120), illustrating Raina’s full figure through four temporally and spatially different areas: lying in bed at bedtime; lying in a field; lying on the couch with a book; and lying in a bath (Guts 120). Raina represents herself as prostrate in this composite image, depicting the day-to-day experience of anxiety immobilizing her. However, the captions in each horizontal panel of the overall polyptych, create an active and cyclical call-and-response type of internalized dialogue that emphasizes Raina’s continual self-examination, repetitive worries, and inability to solve or answer these recurring self-posed inquires: “Was puberty to blame for my stomach aches?/ I don’t know./ Was puberty to blame for my sudden panic attacks?/ I don’t know!” (Guts 120). The repetitive wording of the phrasing emphasizes the recursive experience of her anxiety experience while depicting its fragmentary effect on Raina, which consequently prevents its verbal expression.

Telgemeier often indicates this inadvertent self-silencing by composing wordless sequences that demonstrate both silent dialogue and thought processes. Depicted conversing with her therapist, Lauren, on pages 82-83, Telgemeier shows Raina conversing on several subjects both pleasurable and stressful by including images of the conversational topics in the speech balloons: Mr. Abrams, her family, her friends, comics, Michelle (Guts 82-83). However, when Lauren suggests that Raina should redirect her reflection onto herself (indicated by two question marks that point towards Raina) Raina’s response devolves from pictorial representation to symbolic references of a silent pause and confusion – the ellipsis and the question mark (Guts 83).

Telgemeier similarly indicates the stress of hypothetical situations in a visual-verbal combination by repeating increasingly larger thought bubbles not with fully-formulated verbalizations of her worries but the hypothetical place-marker “What if” (Guts 87). The repeating enlarging phrase in the panel crowds Raina, emphasizing the claustrophobia of her uncommunicated recursive and catastrophic thoughts. Such hypothetical scenarios are also depicted in visualized thought bubbles, once again illustrating her inability to verbalize her thoughts. Anticipating verbally stigmatic reactions from her friends about attending therapy such as Jane accusatorily asking, “Is something wrong with you??” and “Are you crazy?!!” (Guts 113), prevents Raina from sharing her experience of anxiety with others.

Telgemeier shows how the verbal-visual medium of comics can manipulate and reformulate understanding and reduce verbal stigmatization while enabling a reunification of multimodal expression with oral communication. Transforming her therapist’s Anxiety Scale – a “Scale of one to ten./ Where one is…/ maybe a raised eyebrow…/ and ten is losing all control” (Guts 149) – Telgemeier shows a numerical association with each depiction of anxiety Raina has experienced over the course of the book. These depictions include a range of symbolic colors, sound effects, emanata, and facial expressions. Level 1 Anxiety shows a raised eyebrow and a light green haze infiltrating the blue background from the bottom of the panel. Level 2 depicts wider eyes and a darker two-tone light green background. Level 3 increases the darkness of the two-tone green background, while increasing the shocked facial expression and frightened, hunched body-posture. The fourth level shows yellow, shivering emanata with teeth-chattering sound effects. The fifth level indicates red stars of pain and a doubled-over posture with a grimacing facial expression, while the sixth level includes sweat beads and gasping sound effects. The seventh level features shouting and jagged emanata surrounding Raina all the while the green tone background has darkened significantly. The eighth level shows Raina sprinting with motion lines while the ninth level shows a green-eyed Raina with these same lines as sweeping her off balance into a blackening background while the tenth level only depicts open hands that indicate her falling out of frame entirely on a completely black background. This progressive scale depicts the synesthetic experience of anxiety through many compositional elements such as color, texture, sound effects, and emanata. While this verbal-visual anxiety scale helps Raina identify her current and future emotional landscape, it also effectively changes the landscape of the book for the reader when it is introduced three-quarters of the way through the book, recoding our understanding of Raina’s visualized anxiety.

Telgemeier shows how the verbal-visual medium of comics can manipulate and reformulate understanding and reduce verbal stigmatization while enabling a reunification of multimodal expression with oral communication. Transforming her therapist’s Anxiety Scale – a “Scale of one to ten./ Where one is…/ maybe a raised eyebrow…/ and ten is losing all control” (Guts 149) – Telgemeier shows a numerical association with each depiction of anxiety Raina has experienced over the course of the book. These depictions include a range of symbolic colors, sound effects, emanata, and facial expressions. Level 1 Anxiety shows a raised eyebrow and a light green haze infiltrating the blue background from the bottom of the panel. Level 2 depicts wider eyes and a darker two-tone light green background. Level 3 increases the darkness of the two-tone green background, while increasing the shocked facial expression and frightened, hunched body-posture. The fourth level shows yellow, shivering emanata with teeth-chattering sound effects. The fifth level indicates red stars of pain and a doubled-over posture with a grimacing facial expression, while the sixth level includes sweat beads and gasping sound effects. The seventh level features shouting and jagged emanata surrounding Raina all the while the green tone background has darkened significantly. The eighth level shows Raina sprinting with motion lines while the ninth level shows a green-eyed Raina with these same lines as sweeping her off balance into a blackening background while the tenth level only depicts open hands that indicate her falling out of frame entirely on a completely black background. This progressive scale depicts the synesthetic experience of anxiety through many compositional elements such as color, texture, sound effects, and emanata. While this verbal-visual anxiety scale helps Raina identify her current and future emotional landscape, it also effectively changes the landscape of the book for the reader when it is introduced three-quarters of the way through the book, recoding our understanding of Raina’s visualized anxiety.

The reader, who has experienced this visual coding throughout the book – including a dramatic opening splash page sequence of Raina trying to hold onto her environment and her story structure by desperately attempting to stay in panel and eventually falling through (Guts 22) – recodes the sequence of events in terms of their numerical value and corresponding intensity of anxiety. The verbal-visual scale also shows the reader that Raina’s response to anxiety triggers may not undergo a gradual escalation but that triggers may provoke a sudden high-level anxiety response. Seeing Raina gasping, shouting, or with red stars emanating from her, no longer describes a blanket depiction of anxiety, but a measurable response along a continuum associated to a describable state that corresponds to a visual signifier of anxiety – a complex depiction that is not as straightforward as the word “sick” implies earlier in the text. “Sick” indicates a binary state between wellness and illness that is overturned by Telgemeier’s verbal-visual anxiety chart; “sick” introduces a myriad of discrepancies between speaker and listener; “sick” does not imply the brain-body (dis)connection, or the recursivity that Telgemeier’s visual depictions of verbalizations corporealize in Guts.

Telgemeier’s work may feature a child-protagonist and may be read by children, but her compositional complexity within and across her autobiographical graphic narratives is as thoughtful and nuanced as the comics medium permits. By formulating difficult subject matters like illness, fear, social power dynamics, identity, and mortality in a verbal-visual medium like comics, Telgemeier demonstrates the interconnected layers, understandings, and intricacies of these complex subjects in an easily digestible and appealing manner. It is Telgemeier’s mastery of the comics form that lends work like Guts its universal appeal, its widespread popularity, and makes her work highly deserving of sustained attention and further critical inquiry. Critical scholarship of Telgemeier’s work seems to be on the rise, at any rate, and will hopefully continue to proliferate as scholars, educators, librarians, and other parties invested in multimodal forms of communication continue to critically engage with her graphic literature.

Telgemeier’s work may feature a child-protagonist and may be read by children, but her compositional complexity within and across her autobiographical graphic narratives is as thoughtful and nuanced as the comics medium permits. By formulating difficult subject matters like illness, fear, social power dynamics, identity, and mortality in a verbal-visual medium like comics, Telgemeier demonstrates the interconnected layers, understandings, and intricacies of these complex subjects in an easily digestible and appealing manner. It is Telgemeier’s mastery of the comics form that lends work like Guts its universal appeal, its widespread popularity, and makes her work highly deserving of sustained attention and further critical inquiry. Critical scholarship of Telgemeier’s work seems to be on the rise, at any rate, and will hopefully continue to proliferate as scholars, educators, librarians, and other parties invested in multimodal forms of communication continue to critically engage with her graphic literature.