From The Comics Journal #206 (August 1998)

In The Comics Journal #200, R. Fiore called Peter Bagge “the outsider with an entertainer’s instincts,” as good a description as any for one of the most popular, influential and, oddly, underappreciated cartoonists of the last two decades. “Cartoonist” may be too limiting — one can make a case that Bagge is one of the great figures in American comedy during that same period. Between Neat Stuff and the two very different halves of his series Hate, Bagge skewered the occupational frustrations and false family values of the Reagan/Bush ’80s, the aimless, youthful energy of the early ’90s and the fussy ambivalence permeating the end of the millennium. Bagge’s work inhabits American culture like no other writer or artist, and it shouldn’t surprise that several high-profile, mainstream-friendly, pop culture phenomena echo his work from all three periods.

So let’s all stop for a moment and listen to the outsider-as-entertainer, a few months after he brought the best-selling alternative comic in North America to a graceful end that somehow managed to feel right to the creator and reader. The following discussion with Gary Groth puts on display a smart, funny conversationalist holding forth on issues ranging from his MTV “experience” trying to adapt Hate to the TV screen to his thoughts on the state of the art form, to his plans for the future in comics and out. It’s a lot of fun.

—Tom Spurgeon

WHERE YOU’VE BEEN, WHERE YOU’RE GOING

GARY GROTH: By my reckoning, you just turned 40.

PETER BAGGE: Right.

GROTH: How do you feel about where you are in terms of your cartooning? You’ve ended the magazine you worked on for 30 issues. You’re sort of at a crossroads, I think —

BAGGE: You bet!

GROTH: You’re not even entirely sure you’re going to be doing comics, because you might be interested in getting into other media?

BAGGE: Right. Well, I’m getting more sure about the fact that I’ll still be stuck in comics [laughter] —

GROTH: However much you want otherwise.

BAGGE: Exactly.

GROTH: So how do you feel about what you’ve done, what you’ve accomplished, and where you’re going to go?

BAGGE: Yikes! That’s a big question. I feel pretty good about what I’ve accomplished. You know, I’ve been quite the workaholic for the last... gosh, 20 years, and I’ve accomplished something that I’ve always hoped for roughly ten years ago, and that was simply to be able to make a living doing my own comics. Plus I’m now able to support a family. So I get to play Ward Cleaver while I continue to indulge myself doing these silly-ass funnybooks. Who woulda thunk!?

GROTH: And ten years ago, you couldn’t —

BAGGE: Ten years ago was right about when I started making what resembled a livable wage. But yeah, it wasn’t until like 1989 — that was the first year I made a five-figure income [both laugh] in my whole life. Of course, [my wife] Joanne was earning a respectable income ten years before I finally started making decent money. But since then everything started to snowball. It was the accumulation not only of Hate selling so much better than Neat Stuff did, but also all those back issues, and then you started collecting them into bound volumes, so I was making more in royalties — making money off the sweat of my youth. You know when I started out back in New York I thought that my main source of income would be or could be illustration work, but I wasn’t much of an illustrator; that type of work just wasn’t for me. I wasn’t cut out for it. I was a failure, basically, as an illustrator. [Laughs.] By the time I moved to Seattle, I gave up the idea of making a living as an illustrator. But then, thanks to the success of my comics, I started getting phone calls, and I started getting lucrative work, which I still do on occasion, which was great.

So things just began to accumulate, and that’s still more or less the case. Right now, I just finished a big job for Details, and I’m in the middle of another really exciting good-paying job for EMI, illustrating this little songbook thing I think I told you about. And there’s a few other things. I’m assembling that little Hate Jamboree thing. I’m writing the history of Hate, and it’s been fun, just going on and on about how great I am.

GROTH: Is Hate Jamboree going to be all Bagge?

BAGGE: Yeah, mostly. I’m just going to reprint a bunch of stuff that has appeared in obscure places, as well as magazines like Details, but that probably a lot of Hate readers may never have seen. There’s a lot of obscure stuff. I didn’t know that there’d be enough to fill up a 64-page book, but I’ve dug up plenty of stuff, rare illustrations and what have you. But the main inspiration for it is just to make some quick and easy money off of reprinted material. [Laughs.]

GROTH: Of course. [Laughs.]

BAGGE: While also talking about — you know, “Wasn’t Hate wonderful, by gum?” [Laughs.] No, it’ll be a good product, well worth the cover price.

GROTH: Do I detect that even though you’re real happy with what you’ve accomplished, and happy you can earn a living doing cartooning, that there’s still an element of dissatisfaction?

BAGGE: Um, more like an element of panic. [Laughs.]

GROTH: Where does panic come from?

BAGGE: Well, as I said, ten years ago I never would have thought that I would make a living off of my comics. And since then, another thing that I never thought would happen would be people approaching me about doing movies or TV shows. This was a pleasant surprise, but I never had any hopes or ambitions in that area. My focus and first love and main interest was still comics. I mean, all things being equal, I still would much prefer to remain working in the world of comics than in show business.

GROTH: But all things are not equal.

BAGGE: Right. The money’s a lot better. Plus, five, ten years ago, not just me but everybody else in the world of alternative comics were doing great, inspired work, and new artists kept coming along, so I figured that alternative comics were just going to keep growing and take over the world, and that mine and everybody else’s sales would keep going up. But then, as you know, it just tabled off. By, I don’t know, Hate #10, it reached a certain amount in advance orders, and it stayed there ever since.

GROTH: Well, it increased with the color issues, didn’t it?

BAGGE: Not by much: a couple thousand, at best. Then it slowly went back down to where it was before. Which is terrific, compared to everybody else, and still I’m making a living off of it. But it’s very labor-intensive to keep a comic like that coming out on a regular basis, and I worried that with the comic book biz stagnating, and people growing indifferent towards comics, I just didn’t want Hate to become part of something, or associated with something that had became stale or over-the-hill. So I figured it was a good time to quit while I was ahead. I mean, I’m still real happy with the stories I was writing for Hate. Like this last one I’m real happy with, but I always promised myself not to draw the same character and do the same tide for the rest of my life. And if I don’t make a change when I’m 40, I would imagine it’s only going to get harder to make a change later. It would be a lot harder at 50 to make a change, because I’d be that much more tied to this one character and this tide. It’s only going to get scarier to make a switch by then. What will probably happen is, at some point next year I’ll start working on a new title. I really want to take my time, and that’s why I’m glad I have this freelance work, to buy some time so I can formulate it all in my head. I would like to start a new title that would have some new fresh kind of approach to it or feel to it, and then hopefully maybe some people would be ready to come back to alternative comics, or there might be a whole new crop of people who are ready to read it and get excited over it, and that maybe there’ll be a whole other cycle or wave of interest. I mean, there was this great big bubble of interest and activity in the late ’60s and early ’70s, with the underground cartoonists. By the time I got into underground comics, in the late ’70s, it was pretty much all dead. Everyone was doing one comic book a year, what few still were doing it — Crumb and Griffith and Shelton — and people just told me to forget it, underground comics are dead. But obviously there was this whole new generation of people that had new ideas, and —

GROTH: Rejuvenated —

BAGGE: — in the mid-’80s. So then by the late ’80s and early ’90s, it crested again. I don’t think it was quite the phenomenon that underground comics were. The best-selling underground comics sold fantastic. But it also flamed out pretty quickly. I guess it all started in ’68, but by ’72 or ’73, it was done with. Whereas this second wave, for one thing, it hasn’t completely crashed like the undergrounds did. You know, it’s still —

GROTH: No, no, no, not at all.

BAGGE: It was just like a long... kind of a speed bump. [Laughter.] A long hump.

But as for this interest from the show biz world, it wound up becoming real enough that I wound up spending six months last year in New York trying to develop Hate into an animated TV show, which is an idea that I like. Prior to that, people only talked about doing a live-action “independent” movie, but I can’t see it, personally. And I still can’t make any sense out of the way the movie business works. You know, people just keep feeding me different sets of “rules”: “No, first you need a script, and then you have to fill in — then you do this, and then you get the financing, but you don’t do anything before you get the financing...,” and I go, “Well, you just told me to write a script before there’s any financing.” “Oh, well, except for the script, but you’ll have to do that on spec, of course,” and blah, blah, blah. And then you always read articles about people who made their phenomenally successful indy films on credit cards, or that they started filming before they had a penny, or backing, or distribution. WHATEVER! I’m not interested enough to risk losing my house just so I can make an unwatchable two hour long vanity project. I’m not a movie guy. I enjoy watching a good flick now and then, but that’s about the extent of my interest in motion pictures. Unless someone wants to make it for me and give me money and not ask me to jump through hoops and follow their arbitrary “rules.”

But TV is another matter. [Laughter.] Especially animation. It’s very easy for me to see Hate comics turned into an animated TV show. Format-wise, it’s very similar. Plus, there’s the possibility of making a hundred times more money. That appeals to me, too. [Laughs.] So I gave it a shot, but then just the arbitrary nature of that business reared it’s ugly head.

HATE ON MTV

GROTH: Can you give me the Reader’s Digest version of how you got hooked up with MTV and what happened?

BAGGE: Um... well, let’s see... a friend of mine, Aaron Lee, you know who he is, right? He writes that “Kickin’ Ass” column in Hate...

GROTH: Uh-huh.

BAGGE: He had an idea for how Hate would work as a live-action movie, which I sure as heck never did. He wrote a treatment for a Hate movie, and I liked it. Now, Aaron is a movie guy. He’d love to get into the movie biz. Anyhow, he came up with a great angle for taking a piece of the storyline in Hate and turning it into a movie, with a strong ending and everything. So we made a treatment out of it and shopped it around. I was still hoping that someone would consider turning Hate into a TV show, but everyone I would talk to would say, “No, no way would they ever put Hate on the air, it ain’t gonna happen.” So I was resigned to it being a movie or nothing.

GROTH: How do you feel about looking at each issue of Hate as a sitcom episode? Is that flattering, or do you object to the characterization?

BAGGE: It’s a fairly accurate comparison. I could see a definite parallel there. I mean, I don’t think sitcoms are inherently bad. There’s been some great sitcoms. Of course, most of them are bad, but that’s true of everything.

GROTH: Yeah. I re-read most of the Hates, and what struck me is that how episodic each issue was.

BAGGE: It’s more a sitcom like All in the Family, where people aged and things evolved and changed. All in the Family was such a great show! When I see old repeats of All in the Family, I’m always struck by how inspired I obviously was by it. I ripped it off [laughs], inadvertently.

GROTH: It’s surprising that people wouldn’t notice that…

BAGGE: I think it’s just because one’s a TV show and the other’s a comic. But yeah, I’m really aware of it. I almost get embarrassed when I see that show. The patterns of the dialogue, and the way people react, and the way people blowup. Even the topics of conversation. It’s had a really big influence on my comics.

GROTH: Now that you bring it up, I can see the influence.

BAGGE: Another thing that when I look back strikes me the same way is old Peanuts strips involving Lucy and Linus, the way the two of them react. That also had a really big influence on me — almost to an embarrassing degree.

Anyhow, getting back to MTV... like I said, a number of people expressed interest in this new Hate treatment, including Terry Zwigoff, who we wound up going with, although all basically Terry did was lead me to two friends of his, Ron Yerxa and Albert Berger, who did most of the leg work, as far as making something happen with Hate. It was like this daisy chain of people that was developing: me, Aaron, Terry, Ron and Albert, and eventually a connection of theirs at MTV’s movie division, who expressed interest in it, only he had to show it to his boss, a woman named Judy McGrath. She’s the president of MTV, which is based in New York. She, and the guy who’s in charge of MTV animation, Abby Terkuhle, took a look at it, and they immediately saw it as an animated TV show. This is right when the Beavis and Butt-Head movie came out, which was making MTV a fortune at the time. So they were hoping to find something that would, or could, duplicate Beavis’s formula for success; an animated TV show first, then maybe a movie, etcetera, etcetera. So here finally was somebody who saw Hate as an animated TV show. I was like, “Where do I sign?”

I also wound up talking to [Beavis and Butt-Head creator] Mike Judge around this time, who had some kind of development deal with Fox, where he was supposed to bring different potential projects or ideas to Fox; something like that. He said that if I was interested, he would consider bringing Hate to Fox as a part of this deal. Of course he also has a long history with MTV, with Beavis and all, so we wound up discussing the pros and cons of MTV vs. FOX. And based on everything that he told me, I decided I’d rather try MTV. Now, the money I’d make upfront with a cable network like MTV would be a tenth what it would be from Fox, but he says with Fox — and especially with someone like me, who’s a nobody in show biz terms — they would put me through the meat grinder, creatively and otherwise. Whereas MTV is a much more casual, relaxed place, and they’d almost definitely give me a lot more creative freedom.

Also, MTV seemed like the proverbial bird-in-the-hand, since they were sending me written offers by then, so I decided to make a deal with MTV. In retrospect, seeing how MTV wound up deciding not to air it, I wish I went with Fox. Fox might have killed it, too, but at least I would have made ten times more money. [Laughs.] The money I made with MTV was peanuts, relatively speaking. I mean, it compensated for the time it took away from my drawing board, but compared to what I could have made with somebody else, it was pretty bad. And, man, it was like six months of negotiations just to get the peanuts that I got from them. I had to fight like crazy just for me to keep the publishing rights. And the right for reversion, or they’d own it forever, even though they didn’t green light it. It’s a grim business.

GROTH: How deeply were you involved in all of this stuff?

BAGGE: In the negotiations?

GROTH: Yeah. Did you talk to your lawyer a lot?

BAGGE: Yeah, yeah. Every single time there was any progress made in the negotiations, my lawyer would call me up and tell me what happened. Sometimes it seemed like no progress was being made, and other times, for whatever weird, arbitrary reasons, things would progress very rapidly. All of a sudden they’d be very agreeable, after months of them digging in their heels.

GROTH: Do you have any idea why there were these vacillations?

BAGGE: Well, one thing that seemed to always happen is, whenever I whined to Mike Judge about MTV’s foot-dragging, he’d call and remind, somebody up there, of his deal with Fox. Then the next day, there’d always be a lot of progress. [Laughs.]

GROTH: Jesus!

BAGGE: Yeah, good old Mike Judge. Of course, that could’ve only been a coincidence. [Laughter.]

GROTH: So even though presumably it was in their own best interests to move this along —

BAGGE: They just get easily distracted. I was told that, that seems to be a characteristic of MTV: that they’re really hot on one idea one week, and then they cool on it the next week, because something else came along that somebody told them is “the next big thing.” Suggestible bunch, I guess, not unlike their audience. So it was just a matter of keeping them interested. You know, keep the fire under them lit somehow.

GROTH: You cut a deal with MTV.

BAGGE: Yeah, and I wound up going back and forth for six months, making this animatic, and —

GROTH: Back and forth to New York?

BAGGE: Yeah, yeah.

GROTH: You lived in New York for —

BAGGE: A long time. In a hotel. That was the insane thing, too, and this is another thing about how the “rules” of show business makes no sense. We wasted six months negotiating these terms, and what I agreed to, like I said, was nothing, relatively speaking. But by dragging it out, not only am I paying all this money to my lawyer, they’re spending all this money on their lawyers just to have all the lawyers beat each other up. But then my lawyer demanded that I get first-class hotel accommodations, that I fly first-class back and forth, and MTV agreed to this! So it’s like $1,500 round-trip tickets to New York — one time I think it was like $2,400, just to fly me to New York for one day to take part in a pitch. And they put me up in these $300-a-day hotel suites. I had suites in these high-rise hotels right in the heart of downtown Manhattan. I was working till 9:00 every evening at MTV, you know, and I’d have breakfast and lunch there, and then maybe I’d go out to dinner. Maybe I’d go out to a bar with some friends and come back to this huge, huge hotel room that was bigger than everybody’s apartment in New York. Occasionally I’d invite my poor slob friends over, and they’d all be going, “Jesus!” But most of the time I’d sit in this swank place by myself alone, watching ESPN’s Sportcenter on one of my two TVs while I took a bubble bath in my giant Jacuzzi whirlpool bathtub. [Laughs.] I was living the life of Riley back there for a while.

GROTH: Wouldn’t you have preferred a modest hotel and to have pocketed the difference?

BAGGE: I would have much preferred it. I made that clear to everybody, but my lawyer was like, “This is MTV. Take what you can get.” And as soon as I got to New York, the first day I was there, I went to the guy who cuts the checks, and said, look, you’ve got me on this miserable 40-a-day per diem, which barely gets you through lunch in that town, but you have me in this ridiculous hotel room. That hotel room is costing MTV 300 bucks a day, yet I’ll gladly check into the Chelsea for a hundred bucks a day, you add a hundred bucks to my per diem, and you’re still a hundred bucks ahead. You’d be saving a hundred dollars a day. Look at this wonderful favor I’m trying to do for the stockholders of Viacom!” But he just went “Nope. That’s not the way we do things around here.” [Laughs.]

GROTH: Well, if it included room service, then you really had it made.

BAGGE: Yeah, but it didn’t, unfortunately. The incidentals in those posh hotels cost a fortune, which I found out the hard way.

GROTH: So you couldn’t really afford room service at the hotel where you were staying.

BAGGE: God, no. Like, one day I decided to spoil myself and had a really big fancy breakfast delivered to my room. That blew three days worth of my per diem.

GROTH: So when you were working at MTV, I assume this was a very collaborative process, which you weren’t used to, since you work solo.

BAGGE: Yeah, but I didn’t mind it. It was fine. Because I liked the people there. One thing that’s regrettable about things not working out with MTV is I really did like the people there. There’s a big difference between MTV animation and MTV proper — there’s one skyscraper, 1515 Broadway, and that’s where MTVs main offices are. That’s the “Viacom Building,” in which MTV takes up a floor or two. That’s also where the people who run MTV, like the president of MTV is... that’s where they have the board meetings, it’s where all the Board members’ offices are. And it’s pretty much exactly what you think it would be like: It’s all about ego and image there, and everybody’s cubicle has a photo of themselves arm-in-arm with Ringo Starr or Courtney Love. When I first saw that, too, I was like — “Wow, look at that, you got your picture taken with Ringo Starr!” But after I saw that everybody had one, I was like — “Oh man, Ringo’s a whore.” [Laughs.]

GROTH: He would have his picture taken with anyone.

BAGGE: [Laughs.] Yeah. Just buy him a drink. And it was all attitude there, it was full of phony-balonies, and I’d get really bad vibes as soon as I’d walk in the door of that place.

But the Animation Department has their studio in a different building. It’s in this big ugly skyscraper called the “Paramount Building.” I asked if that has something to do with Paramount studios, whom Viacom bought out or vice versa, but nobody seemed to know. A lot of the live TV shows that MTV produced themselves were also filmed in that building, one floor up from the Animation Studio. I can’t even remember the names of these shows — all this God-awful crap that they air, really cheaply made garbage, although somebody out there is watching it: little kids and retarded people.

The Animation Studios themselves were huge and there was a really good work environment there. People there were really nice, and they seemed to be totally removed from all the corporate politics. There was one person I knew already from way back when, who I think you know, too, Anne Bernstein. She’s a story editor there, and she was assigned to work on Hate —

GROTH: Didn’t she work for Nickelodeon?

BAGGE: She used to put together Nickelodeon Magazine’s comic section, and I think she was an art director there as well. She even dabbled in comics herself — she did the first cover for Drawn & Quarterly Magazine, in fact.

GROTH: Right. And then she moved to MTV?

BAGGE: Yeah. I think she tried being a freelancer for a while, and then applied for a position at the Animation Studio. When I first got there, she was still a freelancer or a part-timer there, even though she had her own little office, but now she’s full-time. She helps develop new shows, and she’s written some scripts for Daria — have you ever seen that show, Daria? While I was there, they finished production on Bevis and Butt-Head. They don’t produce those any more, the TV shows. Meanwhile, they started up a new show called Daria. Daria was a character in Beavis and Butt-Head, and because they owned the rights to her already they pulled her out and gave her, her own show. She’s like this very emotionally flat, one-noteish, know-it-allish type teenage girl. It’s a horrible show. I can’t get into it at all. It’s almost unbearable for me to watch, it’s just a nightmare. [Laughter.] And Anne was writing scripts for it. [More laughter.] Seriously, it was a good break for her, and she was determined to make the most of it, so I tried to keep my snotty, resentful remarks about that show down to a minimum when I was around Anne.

GROTH: Is it successful?

BAGGE: Apparently. It’s successful enough that I think it’s going into it’s third season. Yeah, it has its fans. It’s not like a phenomenal success, but it’s doing well enough. You know, it appeals to a certain type. It gets great reviews. Because, you know, it’s supposed to be a “smart” show — “At last, a smart female character!” Stuff like that.

GROTH: Right. [Disgusted snickering.]

BAGGE: Anne was assigned as the story editor on Hate while it was in development, so we worked together a lot. Now she’s the story editor or head writer on another animated show called Downtown, which I guess will premier late this year or early next year, I’m not sure.

GROTH: So how did your collaborative process work? You worked essentially on one pilot, correct?

BAGGE: Yeah. Not even. It was an eight-minute “animatic.” You’ve said it, haven’t you?

GROTH: Yeah.

BAGGE: It was this limited animation thingie.

GROTH: And so it was your job to write this.

BAGGE: One of them. They gave me certain guidelines that I had to follow. One was to make an animatic. I didn’t want to make an animatic, because they showed me a bunch that they had already made, and they’re not much to look at. They’re all boring, awful looking things. They’re basically like a filmed storyboard, with a finished sound track. But they don’t animate the in-between poses. They just “morph” from one pose to the next, as opposed to being fluid motion. They showed me the Daria animatic, which I don’t think was even three minutes long, five minutes long, although it seemed like it went on forever. But they told me it tested really well, and that’s why they made a TV show out of it. They showed it to me because it was a “successful animatic.”

They make these things because they’re a lot cheaper than making animation, and they’re made only to show to focus groups. Anne totally disagrees with me on this, we would argue about this constantly — she goes to a lot of these focus groups, which she thinks are useful, necessity even, and obviously her bosses feel the same way. They live and die by these things, it seems. She also thinks animatics are useful, and that the people at the focus groups can glean enough from seeing this thing to judge if the show will work or not; that they can use their imagination to “fill in the blanks,” to picture in their minds how the animation will flow, which I don’t see at all. Like, could you imagine an animatic of —

GROTH: Fantasia?

BAGGE: Or Ren & Stimpy. If you saw an “animatic” of Ren & Stimpy, would you be able to fathom what the finished show would be like? Would you still be able to “get” the “jokes”? In a cartoon like that, the motion is everything. The jokes are all told by the way an arm would start out slow and then snap back. The joke is in the timing of the action, as opposed to the action itself. It’s not unlike a joke being told by a robot with a monotone voice. It’s still a “joke,” but nobody’s laughing.

I mean, I think this Hate animatic I made is the best one I ever saw. It’ll be in the Animatic Hall of Fame one day [laughs], but so what?

FOCUS GROUPS

GROTH: What is your objection to focus groups?

BAGGE: They didn’t like Hotel. [Laughs.]

GROTH: That’s what I thought. I had an idea you would be pro focus groups if they loved Hate.

BAGGE: What I would have much preferred is if they made a fully animated cartoon, even if it was short, and aired it on one of these shows that they already have on the air, like Cartoon Sushi, which is a bunch of little short animated gag things of different styles. They used to have a show called Liquid Television, and in fact that’s where Beavis and Butt-Head first appeared. They should “focus group” it that way. Like, you have a TV station that’s being seen at any given moment by hundreds and thousands of focus groups, and you’ll get a much better, more democratic response to it, everybody’s watching it by themselves, for the most part. They’re sitting in their house by themselves or with a friend, and if there was just some way you could respond that way rather than gathering people in a group, because a mob mentality often takes place.

For example, somebody told me about this show that I think was on MTV, some late-night show that they came up with just to fill up airtime, where they took a group of people who were like MTV’s core demographic — late teens, early 20s. They’re like college kids. And they would show old classic videos, like they showed some old Prince video, I believe it was the one for the song “Kiss.” And you know, it’s Prince — he’s prancing around and wiggling his ass as always, just being Prince, and [laughs] —

GROTH: And focus group should love that.

BAGGE: So they cut to this panel of young people and they said to this one guy, what did you think? He goes, “Ooh, that’s a classic video, I can remember years ago when that was on the air, I was like such a big Prince fan at the time, and Prince is one of the all-time greats, and he’s one of the big stars of the history of video, and that’s a great song, it’s a classic. What can I say?” Then the next person more or less says the same thing — it’s like “I’m not as big a Prince fan as that guy is, but you know, he’s a talented guy, and blah blah blah.” But then they got some smart ass who’s got an axe to grind, because she started going, “well, I don’t know. Prince objectifies women, I always found him to be incredibly sexist, and that video is a classic example of how sexist he is, the way he objectifies women,” and so on. OK, so now everyone’s on the defensive. “Prince fan” now equals “woman hater.” So the rest of the panel was like, “Well, yeah, yeah, now that you mention it, I guess he is pretty sexist...” So if this was something being focus grouped, the girl with the big mouth and the political agenda would have torpedoed it.

Unfortunately, I wasn’t there when they tested Hate. I told them I wanted to go, but they sent me back to Seattle. They told me that they don’t like having the creator being there, because besides risking him having a nervous breakdown, the other people can’t talk objectively about what’s going on for fear of hurting my feelings, in case it’s being trashed or whatever.

MTV’s own research department conducted these focus groups, and they wrote a report that actually was extremely favorable. I was flabbergasted when a copy got faxed to me because it acknowledged that some people were critical of it in the focus groups and why, but they said overall it tested well, and that compared with a lot of surveying and demographics they’ve been doing to find out why MTV has been doing bad across the board. They said that Hate is something that could correct that. They created this “filter” or litmus test, and they put Hate and other potential new programs through the filter to see how it would stack up, and if it would help MTV’s long-term ratings, and Hate did really well. So this report strongly urged MTV’s board to green light it.

What was so shocking about this is that two of the people who did go to these focus groups were Anne, and Yvette Kaplan, the director. The two of them were very committed to Hate, almost as much as I was myself. They really believed in it, and they worked really hard. And they both came back totally devastated by the reactions of these focus groups.

GROTH: Because they felt they were so disastrous?

BAGGE: Well, maybe she was just girding herself, but the director, Yvette, went in totally expecting it to do great. We worked late one night finishing up the animatic, and the very next day, they sent me to Seattle, and Anne and Yvette went with a couple of other guys to the “testing sites.” They went in expecting it to do just great, and I guess they were thrown for a loop when people started criticizing it. They told me a lot of the kids said Buddy Bradley was “boring.” They thought he was a boring main character. But then, they’d also talk about how some of the girls found him kind of abrasive, obnoxious. You know, can you tone him down and make him likable?

GROTH: Or boring.

BAGGE: And then I said, how can we address all of these criticisms? You know, how do we address him being too boring and him being too abrasive at the same time?

GROTH: Right.

BAGGE: Well, that was our next job — to figure it out! [Laughs.] I guess make him more like — I don’t know, Tim Allen. Turn him into Rosie O’Donnell, I don’t know. The inconsistencies and contradictions that I heard in these criticisms made them impossible to “address,” in my opinion, but we tried anyway.

So rather than give Hate the thumbs up or down, the MTV board gave us a stay of execution. Anne and I were assigned to work on a full length script that I thought came out really good, but when we presented it to the board for a second shot at a green light, most of the board members reacted like they smelled a rotten egg, and I was sent packing for good.

But you know what, it’s funny that I’ve digressed to this degree, because all of our efforts were now moot by this point. A lot had changed in the last few months I was there, in that there was a new guy who they just brought in from another network, who had scored a big hit with some other show, so he came riding into MTV on a white horse. He apparently was given a lot of control over programming, and as so often happens in that biz, he killed everything in sight that was in development, including Hate, so he could start with a clean slate, so to speak. I like to think that Hate was just a victim of circumstances in the end. Of course this guy told me himself that Hate would never work as a TV show, that Buddy is too passive a character, etc, etc, but I like to think that he was lying his head off to me to let himself off the hook. [Laughs.] Hey, my ego is at stake here! Seriously, though, I didn’t agree with a word he said. Of course I didn’t! But that’s my tough luck. Them’s the breaks. Like I said, I shoulda gone with FOX! [Laughs.]

Didn’t you originally ask for the Reader’s Digest version of my MTV experiences? Well that would be it: “I shoulda gone with Fox. The End.”

GROTH: Well, you must really resent the political —

BAGGE: Yes and no. It’s all a crapshoot. I knew that going in. Matt Groening would always say that he felt like he won the lottery by getting a TV show. Although to be fair, Matt had a bit more going for him than the average shmoe. Also, it’s such a high-stakes racket; the payoffs can be huge. Trying to get a television show puts me in competition with people who would kill their mothers to get a TV show on the air, and —

GROTH: You wouldn’t kill your mother to do it?

BAGGE: No, no, I wouldn’t. My dad, maybe. [Laughs.] But people who would be willing to kill their dads are a dime a dozen.

GROTH: Right. Well, how do you feel about having invested a substantial amount of time into this, and not getting much tangible out of it?

BAGGE: Yeah, but I got paid. You know, it was like a job. In that sense it wasn’t all that much of a gamble. It screwed up Hate’s schedule, but I was leaning towards making Hate #30 the last one, anyway, so by having Hate’s schedule slow down over the last year, it’s no big deal. And then once I got home, I picked up speed.

GROTH: So you don’t resent wasting the time doing it?

BAGGE: Nah. I really thought I would. I thought I would go nuts, because I was working so hard on the thing. I figured this was a golden opportunity, I wanted to make the most of it, so I busted my ass. Plus I thought it was coming along rather nicely. Hate would’ve been a great show, Gary! So I felt like the payoff was within my grasp.

GROTH: Would you have found that as fulfilling as drawing the comic, to be involved in a TV show?

BAGGE: Yeah. At MTV, yes. When I first got there, before I knew what I was doing or what exact direction to take with the show, we had lots and lots of meetings with the people in the Animation Department, where everyone would throw their two cents in about everything, and a lot of what they said I had no use for, or even totally disagreed with. I don’t even know if they really meant half of what they were saying, or if they were just throwing shit out there. And sometimes I’d be sitting there like, “Ah, this is so stupid, this is such a waste of time, or, this person doesn’t get it.” But every now and then somebody would say something that was a great idea. And I’d go — “Yeah! All right!” They’d basically come up with something that I wouldn’t have come up with on my own. So for that reason, ultimately I didn’t mind collaborating and hearing what other people had to say. If they didn’t like an idea, I would throw it away, and if I liked it — makes me look better, so what the hell. And they rarely — except for making an animatic — forced anything down my throat.

This basically is why l went with MTV, and I gotta credit Abby for taking this approach with me. It could be argued that he gave me enough rope to hang myself [laughs], but he did give me a lot of slack. I was basically my own boss the whole time I was there.

GROTH: What did you discuss during these board meetings?

BAGGE: Everything. What story to do for the animatic. Originally it was supposed to be the story from Hate #3, and then for various reasons Abby convinced me that the story from Hate #1 would be better. I remember Terry Zwigoff coming up with a good argument for the story from Hate #2 — He had a good suggestion for condensing it into an animatic, but by then it was too late. We were well underway with the Hate #1 idea, which Terry wasn’t keen on. Terry and his partners were very good sounding boards, I gotta say, especially Albert [Berger], but Terry operates at such a slow and deliberate pace. He’s way too slow for television. [Laughter.] By the time he’d return my phone calls it would usually be too late to incorporate his input. Poor Terry was always being left in the dust. [Laughs.]

GROTH: You didn’t object to this committee process if having to sift through this democratic mélange of ideas and input?

BAGGE: No. I would have objected to it if: a) people forced shit down my throat, and b) I didn’t like what they were forcing down my throat. But they didn’t. That seemed to be their M. O. Also, once the meetings started to seem to be dragging, I asked Abby if we could stop having them so I could just work with the director and no one else at that point, and he complied.

GROTH: It still sounds like the whole committee process mitigated your best instincts.

BAGGE: Well, like I said, I wasn’t keen on making an animatic. And I suppose I could have made a really big stink about that. Maybe I could have had a total temper tantrum and said, “No animatic, we’re making a finished cartoon.” But, I just got there, and I’m not used to this whole environment, and here’s this Abby guy saying, this is what we do. We make animatics. Then we show ’em to focus groups. And I was like, “You’re the expert.” What do I know?

GROTH: I can imagine that would be fairly intimidating.

BAGGE: Right! And when I did go against my own instincts, it was based on their experiences. You know, they were the experts in the TV biz, and I’m not. But after a while, they did have a hard time totally understanding the whole stylistic approach. Like the way I perceived the comic, I wanted it to be really bouncy and lively, in spite of the fact that the characters are fucked up, and it’s called “Hate.” Whereas they took all of that very literally, and they thought it was going to have a really gloomy dark uh-uh-uh, with a really heavy death metal soundtrack, and here I was bringing in Louis Jordan records, really bouncy stuff. I was like, “No, it’s a cartoon — I want it to be really cartoony,” and they kept saying, “Well, isn’t that going to conflict with the content?” And I said, “No, no, it will give it an ironic twist.”

My drawing is real cartoony, and I wanted it to look real cartoony. At one point, all of a sudden, the director, Yvette, she suddenly [got] what I was driving at, and got really excited. From that point on, she was very enthusiastic about the whole project. She’s still bummed about it getting killed.

GROTH: So this whole process hasn’t sowed you on the possibility of getting Hate up there —

BAGGE: No. Up until then I was basically a spoiled brat, in that I was really inclined to just sit in my house in Seattle and hope that other people would do everything for me. And again, the people who have TV shows, they’re people that just pack up the family — or leave their family — and sell the house, or take out a mortgage on it, and they go down to LA and couch surf, and they just whore themselves, and bust ass. I’m just not willing to make that big a sacrifice. I’ll never move to Los Angeles. If I was single I would, to tell you the truth. But Joanne said no, never, ever, especially not with a kid. I’d feel stupid bringing the whole family down there, just so I could run around town sucking cock. [Laughs.] But if I was single, who knows, maybe I would, what the hell? It would be my “chosen lifestyle.” [Laughs.]

GROTH: Now, Joanne would object to that, even if there was a definite possibility of a big payoff?

BAGGE: Er, no. [Laughs.] Like with the MTV thing, if they did pick it up, I would probably have had to spend at least another solid six months in New York. And Joanna’s from New York, she doesn’t mind New York City, but I asked her again, “Would you want to live in New York for six months?” She said, “No, just live there by yourself for six months.”

GROTH: It’s hard to move for six months with a kid —

BAGGE: Yeah, there’s school, and again it’s New York City, I’m not so sure the kid would be happy there.

I haven’t spent enough time in LA to know for sure if I’d go nuts or not. Mostly what I know of LA is just seeing my hotel room.

GROTH: So anyway, I just want to confirm that under the right circumstances, Joanne would not object to watching you suck cock to get Hate on TV.

BAGGE: Right. [Laughs.] She just wants to be far away while I’m doing it. “Just send me the check when you’re done.”

GROTH: She’s willing to let you do it, but not watch you do it.

BAGGE: Right. [Laughs.]

THE END OF HATE

GROTH: Well now, you told me why you stopped Hate, but you really hadn’t run out of Buddy stories, right?

BAGGE: No. No. And in fact, well, you read the last story?

GROTH: Uh-huh.

BAGGE: The way the main story ended, I immediately saw an opening for a bazillion new stories, seeing how he’s now marrying Lisa and having a baby. So he’s entering a whole new phase of his life. And again, what I always like to do is to keep a ten-year distance between what’s happened in my life and Buddy, since he’s always ten years younger than me.

GROTH: So you can digest your own experience?

BAGGE: Right. So by the time [my daughter] Hannah’s ten, I’ll just have Buddy have a kid, and then... Well, I also ran a letter in the last Hate, where the writer said that he senses in the comic that Buddy’s getting older, fuddy-duddier, and that he was just picking up the hints that Buddy was settling down, maybe even getting married and having a kid, and he was like, “I don’t like this.” He says, “I don’t relate to this stuff, and don’t you think you’ll alienate the readers?” because the average comic reader is in their teens and 20s.

GROTH: Well, how do you answer that?

BAGGE: Ya got me! Guess I’m fucked! Because I’m getting older, and I want to write about stuff that I relate to, and — but yeah, as you get older —

GROTH: It does seem like a Catch-22.

BAGGE: Yeah —

GROTH: Demographically, the alternative comics market is probably predominantly 18 to 25 or so.

BAGGE: And once they get into their 30s, they’ve got a wife and a kid, and they got a house farther out in the suburbs. It’s not worth the time to go down to [local hipster outlet] Fallout [Records] to read more comics about slackers, you know.

GROTH: As you’re busy changing diapers.

BAGGE: Right. Right. Or having a life.

GROTH: So where does that put you? You want to write stuff that’s related to your own life, but you’re getting older than your demographic audience, so —

BAGGE: Right! That we’re all stuck with —

GROTH: This brings us full circle to the panic.

BAGGE: Yeah, there you go. [Laughs.] It’s a good reason to panic. So it’s taken me what, an hour, to finally explain why I’m having a sense of panic? Yeah, almost out of spite, I might change my mind, but the idea that I have is that I’d like to start a new anthology. And it wouldn’t look too different from the way the more recent Hates have looked. I still want to get some color in there, sell ads, but at the same time it would be a cross between what Hate is right now and Weirdo, because once Weirdo died, there was nothing exactly like it. There’s other anthologies that I like, but nothing has that iconoclastic spirit that always floats my boat.

GROTH: Well, maybe I shouldn’t mention this in the interview, but even getting ads would be a little more difficult, because if you’re doing stories that appeal to an older readership, all the advertising that Hate runs appeals to the 18-25 year olds. The content is actually going to be contrary to the target audience of the advertiser.

BAGGE: So we’ll run ads for “Depends”! [Laughs.] What’s the big deal? Plus I don’t intend to make something that’s exclusively for old folks like us. I’ll mix it up. I mean, the fact that it’s an anthology means I’ll be running work by new young people, who I hope will come along. You know, there hasn’t been too many new —

GROTH: You can ride their demographic coattails.

BAGGE: Exactly! But I was thinking, almost out of spite. I wanted to call the magazine “Let’s Get It On!,” something totally outdated and hokey — because sometimes I get embarrassed, I’m self-conscious to even go to a comics convention, where I Just feel like this middle-aged fuddy-duddy now, and... You know, comic fans are looking for the next big thing, and there’ll be some new kid on the block that they’re all follow around while I’m left behind scratching my beer belly [laughs] — so that’s why I think it’s really funny, the really sleazy aspect of it. It’s almost like instead of trying to pretend or act like I’m this pure artistic being, to go the opposite, and just exaggerate the “dirty old man” element of my personality, and that’s why I love the name “Let’s Get It On!,” because it’s so hokey. It makes me think of swingers’ conventions in Las Vegas. And I want to give it a subtitle like “The Magazine for Dirty Old Men and the Women Who Love Them.” [Laughs.] But I already know the effect this is going to have on the average comic reader, because when I tell somebody like [Fantagraphics marketing director] Eric [Reynolds], who’s closer to that younger age demographic, when I tell him the tide and the subtitle, their first reaction is like — “Yecch!” Although women love that. Both young and old women, they love that name when I tell it to them. Like [Roller Derby editor] Lisa Carver, when I started explaining to her what it’s going to be like, she says, “I don’t even care. Any magazine that’s called ‘Let’s Get It On!’ I’d buy in an instant!”

GROTH: Huh! She’d be in her late 20s, right?

BAGGE: Yeah. Well, she’s sort of a dirty old nun herself. [Laughs.]

GROTH: Well, we don’t know for sure what the demographics of people reading alternative comics are. I mean, we’re guessing between 18 and 25 predominantly, but it’s hard to say with any certainty.

BAGGE: I would say with considerable certainty that our readership drops off fast once you get beyond age 25. But I have some ideas of how we could at least try to reach older readers. One idea is to format it like the [Fantagraphics Books] catalogue, and I wanted to do everything that we can to sell as many via mail order, and really play it up on the Net, which is something that we haven’t really tried yet. I’ve been intending for like a year to get a web site going, that’s where people do a lot of their “shopping and strolling” these days, on the Internet. The Journal and the Fantagraphics web sites haven’t been up that long, but it’s a pretty sizable number of people who have at least checked it out. So as long as it’s on there, there are people who would still be buying our comics, except for the fact that they’ve got families and careers. They can’t be bothered to go all the way down to the “hip” comic shop and pay for parking, or find a parking space, but if they see the stuff on the Net, or get it into their hands somehow, maybe even sending it out mail order. You know, like maybe putting out one, a test one, that is most like a catalogue. Or we could take one issue of the Fantagraphics catalogue and kind of introduce “Let’s Get It On!” within the pages of that, because the problem of why people buy comic books, and why they don’t is logistical. I think it’s a geographic problem, as well as a cultural one.

GROTH: Is it your opinion that people drop off from reading alternative comics at a certain age, that they just move into other things at a certain point of their lives —

BAGGE: Yeah, I think that what’s going on in their lives has a lot to do with it, then it just carries on physically and time-wise. Takes them away where they just can’t afford to invest the time and money —

GROTH: But they don’t stop watching movies, or stop watching TV —

BAGGE: No, that’s right, because you can do that without leaving your home.

GROTH: What is it about reading comics that you think makes it easy for them to stop?

BAGGE: Well, one is because you don’t have to go downtown to find a comic shop that will sell alternative comics. They live farther out in the ’burbs, like you do, and even I live right in the Seattle city limits, and I’m ten blocks away from a comic shop that would never carry a single issue of Hate. It’s terrible. It’s right there, in Seattle, and — I mean, there’s nothing out here for you. So the stuff is just not available. The other problem is because older people drop out, it’s not in anybody’s interest to put out comics that would appeal to an older demographic, so when they do go into comic shops, they feel like they’ve outgrown everything, because there’s no reason for anybody to put out a comic book that would appeal to a 40-year-old.

GROTH: I think that’s a real problem with alternative cartoonists who try to do something of a more mature nature, who don’t have an obvious youth angle, somebody like Seth, who can’t be appealing to too many 18-25-year olds. You know what I mean?

BAGGE: How does Palooka-Ville sell?

GROTH: Forty-five hundred copies or 5,000, something like that.

BAGGE: And how old is Seth, too? He’s in his 30s.

GROTH: Thirties, yeah, 34, something like that.

BAGGE: Hmm. You’re referring to the most recent storyline, I assume, where he’s got some old guy in a fan store walking around stirring coffee while he’s telling you via word balloons the story of his life? It’s a unique approach, but not necessarily one that people under 40 are gonna flock to, simply because it’s about an old man. [Laughs.] There was a really funny letter in the second installment from James Sturm, where James says, “Well, I guess if you’re going to break that old rule of ‘show, don’t tell’, you might as well smash it to Pieces.” [Laughs.]

GOTH: Obliterate it.

BAGGE: Yeah.

GROTH: That’s right, go all the way. No half measures. Well now, as far as what you’ve envisioned so far in a new periodical, would your stories still be about Buddy?

BAGGE: I don’t know, I would like to —

GROTH: As a married old codger?

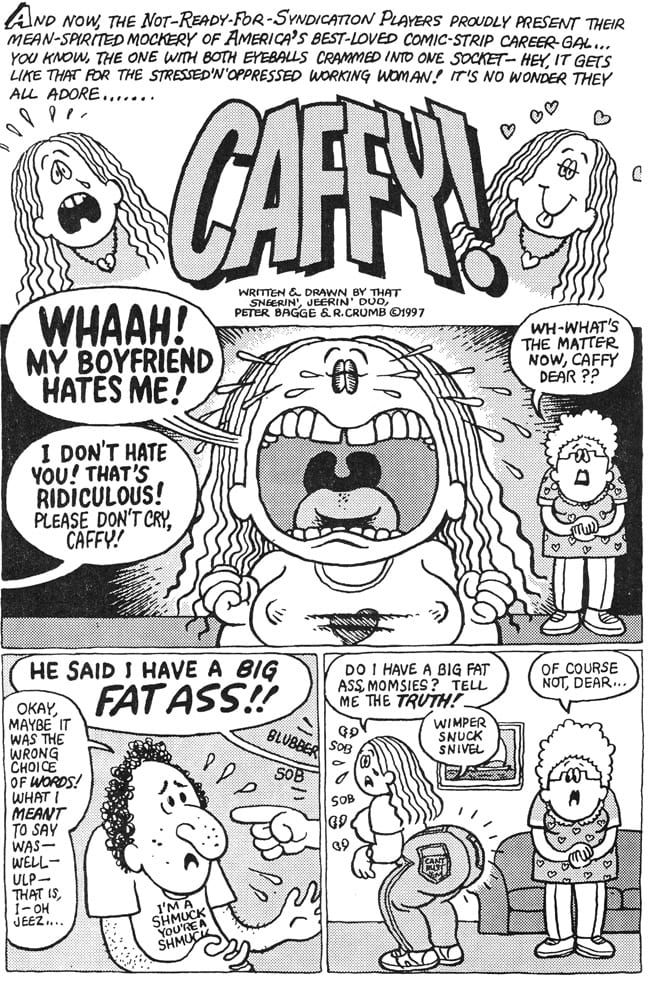

BAGGE: Maybe eventually, but at first, no, I’d like to experiment. I have an idea for a female character that I’d like to do kind of regularly. I really like the way that Cathy spoof came out that I collaborated on with Crumb, I loved working with the character that wound up evolving from that, of “Caffy.” ’Cause she isn’t exactly Cathy. I thought that character and that strip was very funny, like this was about being a more explosive, out-there, fat-assed version of Cathy, although she’s still basically square, part of the mainstream culture. Yet I know a lot of women who are part of the mainstream suburban culture, yet who are still motivated and concerned by the same things that Cathy is, like having a boyfriend or gaining weight. So I really want to come up with a character that’s like that “Caffy” character we made up, only make her a bit of a hipster, more of a weirdo.

GROTH: A fat-assed hipster career girl?

BAGGE: There you go! [Laughs.] Only without a career. [Laughs.] The last time I talked to Crumb, I asked him if he’d still want to collaborate, and he said the same thing he said with the Cathy strip, which was, show me the Story, and if I like it, then yeah, sure. So that would be great if he and I could do a regular or semi-regular character. I really enjoy both creating and the results of the collaborations I’ve been doing in Hate. I just did something with [Alan] Moore, although that was a switch, because I drew it and he wrote it. Although I was very happy with the way it came out. I haven’t heard from him yet about the final results. I hope he’s happy with it!

GROTH: He should be thrilled that any artist draws his scripts after his Big Numbers experience.

BAGGE: [Laughs.] It’s only four pages. But like the thing I did with Adrian [Tomine] and Crumb, of course, and then some with Gilbert [Hernandez]... you know, there’s a handful of artists who I really wish — I wish I did something with Rick Altergott, so I’d still love to collaborate with him. Something of a satirical nature. I was thinking of just taking certain themes, like a mall, and just talk about a mall experience. It would almost be like Mad, but for an older, more fucked-up sensibility. You know, it would be like “behind the scenes at the mall”, the way Mad would do it, but not quite in that by-the-numbers way, the way Mad’s been doing it forever, and not geared towards a 12-year old audience, but hopefully a 30-year old audience. Just take certain things and do something with it, and come up with an appropriate collaborator.

I really hate to draw [laughs], but I almost prefer having somebody draw the whole thing themselves than do that process that me and [Jim] Blanchard are doing at this point.

GROTH: Really?

BAGGE: Yeah, I thought that Blanchard did a great job, and it served its purpose, but I don’t think I’d want to keep doing that. I think in the long run I’m better off if I just draw it entirely by myself or have somebody else completely draw it in their own style. Because there’s always this neither-nor thing about it. For one thing, nobody will buy any original art. People are rarely interested at all in the original art that I did in collaboration with Blanchard. When I ask people why, they say it’s not because it doesn’t look good, because the pages Jim did are stunning in their original form. His line art gets broken up when we scan it into the computer so it can be colored, so the way it appears doesn’t do it any justice. But Jim’s originals are really pristine compared to mine, because I use globs of Wite-Out, and my line work is all jagged and broken up. But when asked, people seem to prefer something that’s the creation of just one person, that’s one person’s vision.

GROTH: You’re burdened by the alternative ethos. Are there aesthetic objections to having someone ink your work?

BAGGE: Apparently. To me it was just something new, something different, and not necessarily better or worse.

GROTH: There’s a marked difference between your inks and Blanchard’s.

BAGGE: Yeah. It smoothed things out, which is what I wanted. What you see is exactly what I wanted. I wanted the stories to flow at a more leisurely pace. There’s something much more manic about my own drawing style. There’s this energy there that’s not there when Jim does it. I didn’t think it would be missed, but a lot of people seem to miss it. I totally understand why, but I really wanted the art in the color Hates to be kind of understated. I was very inspired by the pacing of John Stanley’s Little Lulu stories, and that’s why I went with the four-tiered format instead of three, as well as the color. I like the really simple candy colors, and that really easy, steady pacing of his stories, and that is totally what I tried to emulate with the color Hates, those old Little Lulus. Also Jim’s inks would “trap” the color better — you know, there’s that technical problem with computer coloring where the lines and shapes have to be really tight. And my line work is too jagged, but he smoothed things out, and didn’t make it so rough and tumble.

GROTH: Now, do you tire of drawing—

BAGGE: I’m just sick of drawing —

GROTH: — this, very leisurely-fated strip. I mean, do you ever get bored drawing the same cars and the same interiors, and the same details?

BAGGE: I just get sick of leaning over the drawing table all day. I still like to draw on occasion, but 8-10 hours a day? Ugh, I’ve had it. I really enjoy writing, though. Writing’s a walk in the park, compared to drawing. The writing comes real easy to me, and even breaking it down to a strip, roughing it out. And I love the end results as well, the reward of a job well done. But by the time you get down to doing the finished parts of it, like the finished penciling and lettering and then inking, by then I’m just sick of it. With most cartoonists I know, that’s their favorite thing — they just love to ink! They’ll work all through the night. You know, most artists are night-owls, and they’ll work till four or five in the morning, where you have no distractions, and you kind of go into a “zone.” But I’ve never been that way. I’ve never pulled an “all-nighter.” I work in the day, and as a result I do have many distractions, the kid barging in, and the phone, but I like having the day broken up that way anyway. Whatever didn’t get done that day that needed to get done I finish up after dinner, and then it’s nighty-night for me. I want to be on the same schedule as my family, and Joanne was always in the restaurant business, so she always had to get up early, and I would always wake up with her and go to sleep when she did.

GROTH: Now, the kid comes home at one o’clock or so from school?

BAGGE: Three-thirty.

GROTH: Do you feel compelled to pal around with her when she comes home, or can you discipline yourself so that you’re down in your studio till five or six, or —

BAGGE: Yeah, I have no problems avoiding her. [Laughs.] And vice versa! I mean, by five or six I come upstairs for dinner, and then after dinner we pal around. She usually comes home with a friend these days and just pals around with the friend, which she much prefers than hanging out with me these days. I’m just Old Mr. Get-In-The-Way to her these days.

GROTH: I wish Conrad could be like that. It’s hard for me to get any work done when he’s here. I mean, first of all, he’s always screaming, “Come on out and do something!” And I want to, butt I also want to work. So it’s always a conflict.

BAGGE: Well, Hannah was like that when she was younger, when she was Conrad’s age [four]. Give him time. He’ll hate you soon enough. [Laughs.]

LOTS OF WRITING

GROTH: I re-read most of the Hate’s for the interview. They’re very dense. There’s a lot of writing.

BAGGE: Yeah. You mean like verbose? Or just a lot of story?

GROTH: No, no, not verbose, but a dense narrative. There’s literally a lot of writing, there’s a lot of dialogue, and a lot a panels with a lot of dialogue.

BAGGE: Yeah. I think that both Blanchard, when he started inking it, and Eric especially, the first time he inked something by me, they both were shocked and dismayed to find how labor-intensive it is. They looked at my work, and it’s cartoony, so they thought it would be simple, but they realized that every single little thing in there was a vital piece of information, that I’m not throwing in all these Jack Kirby bubbles and action lines everywhere just to fill up space, that everything’s an object that has to be delineated, you know. Merely going four-tiered, I wound up not saving any time per page when I started working with Jim, because —

GROTH: You added a tier.

BAGGE: Yeah, and then I increased the size of the original, figuring that would give Jim a lot more room to work with. So I work on 14 x 17 paper now, whereas the old black-and-white Hates were 11 x 14. And those were three-tiered. But again. that’s what I wanted to do. But I wanted everything to be really dearly delineated, and I wanted the reader to have more story per page. It’s important to me to give the reader a lot for their money. [Laughs.]

GROTH: How do you construct a story?

BAGGE: I’ve used the same assembly line process for years. First, I’ll write a brief outline of what’s going to happen in the story, and sometimes the outline will be three or four pages. From that, I write all the dialogue, and all the stage directions in long hand, and as I go along, I break it down. Sometimes I’ll write the whole thing like that, and then I go back to the beginning and start to break it down into pages and panels, but after a while it became somewhat formulaic, so that I would pretty much know what would be a good place to end the page on. I use lined paper that comes in pads that are, I don’t know, 5 x 8, and writing in longhand, pretty much would fill up a page, the equivalent both in dialogue and direction as to the amount of content of one page of comics. So when I get to the bottom of the page, I would try to rectify how that page would end, then I would literally draw lines between the different lines of text, breaking it down into panels that way. It’s amazing that it became such an easy system for me. I manage to always end scenes at the bottom of a page. A lot of cartoonists end in the middle of a page. They’ll switch scenes, or even in the middle of the same tier. But somehow I developed this — I don’t know, a shtick. [Laughs.] I somehow figured out a way to always pace the story so that —

GROTH: It’s instinctual?

BAGGE: Yeah, so that a scene, a shift in scene, would always begin when you turn the page, or at the top of the next page.

GROTH: So you see each page as a unit.

BAGGE: Yeah. And the scenes are almost always anywhere from one page to — I rarely had one scene, one setting, that took up more than five pages. And then I take each piece of paper and I paperclip it to a piece of typewriter paper, and I break that down — in ballpoint pen, I draw the whole page, using the text thing as a guide.

I go through the whole thing on typewriter paper, so I’ll have 24 pages of typewriter paper with all the drawings on it. The drawings there tend to be really sloppy and messy, but I like to attack it. When I collaborate with other artists, and send them a rough, I pencil it first, and then go over the penciling with a ballpoint pen or a Rapidograph, so that everything will be really dear, because they can’t read my mind. But when I’m doing a rough for myself, they look like slop, but I know what the “slop” is supposed to be. When I draw really fast, by drawing things really manic, it always seems like the first time I draw something, like somebody’s face, I always get the essence of the emotion that I want right there. So sometimes I’ll be penciling the finished version of that same drawing over and over, trying to capture this manic little thing I drew in two seconds with a ballpoint pen, and failing. After I’ve done that I then take those roughs and attach them to 24 pages or whatever of Bristol paper. I break down on the finished Bristol board the whole page, the panels and everything, and then I trace over that on the tracing paper where I break it down again, and then I draw the whole strip on the tracing paper. That tells me how much room I need for the word balloons, and where to shape everything. So I draw first with a light pencil, then I go over it again with a darker pencil. Then I take that tracing paper and I flip it over and I draw the whole thing again backwards. And I’m making changes all the time, constant shifting things, and changing things. And another great thing too, is to look at the drawing backwards, because the way somebody will be standing —

GROTH: For imperfections.

BAGGE: Yeah. It’s like holding it up to a mirror. Like, the way one character is standing might be driving me nuts, and I can’t figure out why, but then once I turn it backwards, I’ll see it — “oh, he’s leaning way too forward,” so I correct it backwards, and then I lie that down, right side up again on the Bristol board, and take the nub of a colored pencil and transfer the pencil drawings on the back, because I use a very soft pencil when I draw the back of the tracing paper, and the rub that on to the Bristol board, so I have this faint image of every panel. And I shift it, too. Another great thing about doing that transference is, if I decide Buddy’s head should be right in the middle, and it’s a little too low or a little too to the side —

GROTH: You can move it.

BAGGE: Yeah. So I’ll just shift it, and [sound effects] get rid of that, and then I pencil it all over again. [Laughs.]

GROTH: You described this to me before, and I said then that that’s the most laborious process I’ve ever heard an artist describe to me.

BAGGE: Yeah, and lots of times I think I should streamline this, or maybe, all this isn’t necessary, but every time I try to cut out one of these steps, I regret it. It’s just not as good. So I’m stuck with it. But it’s still —

GROTH: The only other artist I knew who does anything remotely similar is Chester Brown. If I remember correctly, he’ll draw each panel on a separate piece of paper, and then he’ll literally paste the panel up after he’s completed it. That’s why his panels are always odd shapes and sizes, and there’s so much negative space on his pages. In a way the panel is an autonomous unit on his pages.

BAGGE: Right, although I doubt he does each individual drawing over and over. He strikes me as one of those guys who gets it right the first time, generally. Actually, someone I believe who draws exactly the same way I do is Jason Lutes. I’m pretty sure he goes through that whole same —

GROTH: Really? Did you poison him with your approach at some point?

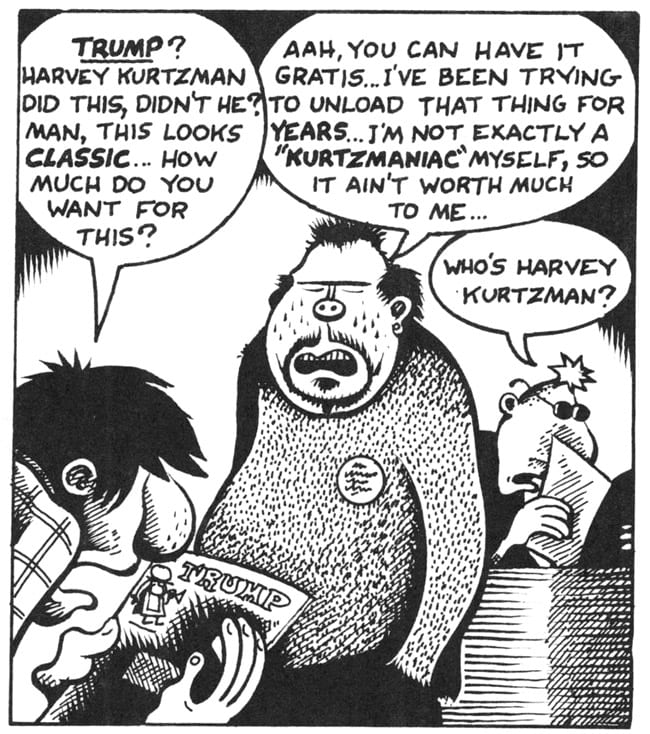

BAGGE: I dunno. I may have. If I did I’m sorry. [Laughs.] I don’t know if I’m the one that gave him — well, the basis of what I do I got from Kurtzman. I don’t know if he always did it, but I was told that what he frequently did when he was roughing out a strip was he would draw the whole thing with a yellow Magic Marker, and then an orange one, then a red one, then purple, then black. He would just draw in five, six, seven layers of color.

GROTH: His black-and-white work?

BAGGE: No, just to rough it out, just to get all the placement and body movement right, just to come up with a guide. Each time he’d go over it with a darker marker. He was just altering the shapes and the poses, and —

GROTH: That’s interesting, because his work is so spontaneous-looking.

BAGGE: Well, that’s why a lot of people are shocked when they find out what I go through, because to them it looks like I just sit down and doodle it. And of course I want it to look nice and breezy. I don’t want people to sit there contemplating on how long it must have taken me to do it. That’s not the point.

LITTLE WHITE LIES

GROTH: We were talking about the new Hate. So you want to go in a radically new direction for a while?

BAGGE: Yeah, yeah.

GROTH: And that’s to maintain a creative vitality?

BAGGE: Yes! [Laughs.] That’s always a good plan, don’t you think? Although it remains to be seen if it works out that way.

GROTH: I think it’s a good idea for anybody to do something like that, shift directions, and force himself into new challenges. I mean, you can get too comfortable.

BAGGE: Yeah. At the same time, though, Buddy has evolved into a very handy vehicle for me to express myself. I mean, he’s very autobiographical.

GROTH: As the years went by, did you find yourself getting a bit divorced from that slacker context?

BAGGE: Well, Buddy was always getting older. He started his own business. He never really was a total “slacker.” He always had some vague ambitions. It was never his intention just to sit around and do nothing. But at the same time, his own hang-ups would hold him back, and he’s got a bit of an attitude problem. That’s what makes him amusing. [Laughs.] But he’s never been a total loser, and in fact, at the end of Hate, the last five issues of the color Hates, he almost ruthlessly erases all the real slackers from his life.

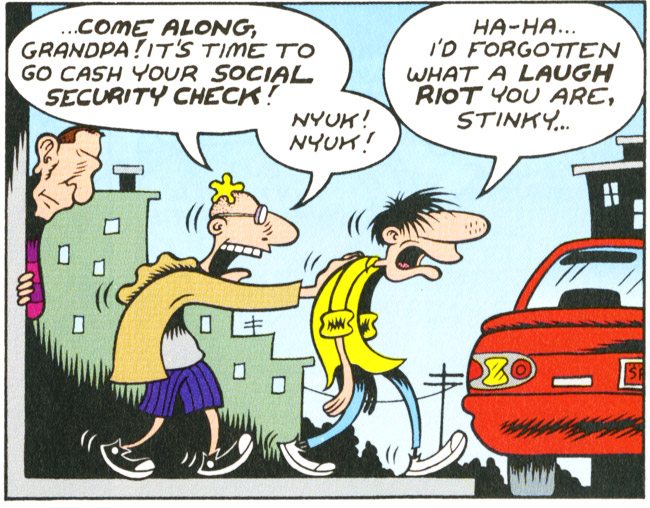

There was a period, I guess it was in #24 or #25, he split up with Lisa, and for simple company, he found himself hanging out with his brother, and his next door neighbor, then Stinky came back to town. So he’s kind of like a bachelor again hanging out with the guys, but Buddy was a lot more mature than they were because these guys weren’t maturing at all and weren’t very smart. The things that they were coming up with to “get rich,” or to occupy their time, were either absurd or criminal. [Laughs.] So yeah, he wound up one after the other, just eliminating all of them from his life. That’s hardly a “slacker” thing to do.

GROTH: Almost everyone in the comic seems to suffer from low self-esteem.

BAGGE: Um, yeah. I mean, you can find people who are worse, though.

GROTH: Well...

BAGGE: I don’t know about Jay suffering from low self-esteem. He seems pretty content with himself. I mean, he lies about being a junkie and stuff like that, but that’s just because he knows how most people feel about that. [Laughs.] I guess it’s not something he’s proud of, but it’s also an illegal activity, so — [Laughs.]

GROTH: But, there’s this weaselly nature to almost everybody in the book to one degree or another, even Buddy…

BAGGE: Yeah, I don’t know if Buddy’s —

GROTH: Squirrelly, weaselly nature.

BAGGE: Well, I want to show how people lie, because everybody tells little white lies. You know, they’re trying to get along, they try to get away with stuff, and I like to show them doing that, because I think it’s really funny. [Laughs.] Like in this last issue, I think what’s really hilarious is when it opens up with Buddy and Lisa and Valerie all having lunch or dinner, and then Lisa goes to the bathroom, and Buddy makes a dismissive comment about her new big butt, and he kind of comes on to Val. “I’ve still got the hots for you,” and she’s like — “Forget it!” And she even says, “I bet you think Lisa’s big butt’s real cute, I bet you want to fuck it,” and he’s like, “Nah, no way,” although of course it’s true. And then, as soon as Val’s gone, Lisa’s like, “I bet you still have the hots for Val,” and he denies it, but that’s true as well! [Laughs.] The girls both know what he’s about, but at the same time he can’t flat out admit they’re right because they’ll be offended. Then he would really blow his chances with either of them!

GROTH: Right, right.

BAGGE: So I’m trying to be true to human nature.

GROTH: There are a lot of butts in — I wouldn’t go so far as to say there’s a butt fetish, but butts are prominent in Hate.

BAGGE: Oh, really?

GROTH: Yeah. Are you aware of that!

BAGGE: No, I’m not. [Laughs.] Female butts, I assume you mean?

GROTH: Yeah, entirely female butts, I’d say. Val disappears for awhile, like in Hate — I don’t know, #7 or #8 or #10, she goes away for a while, and then she comes back, and she’s much skinnier. She has a bony butt. Buddy’s really turned off by this —

BAGGE: Right, right. So you mean like — not so much like me drawing butts obsessively, but references to them?

GROTH: Yes.

BAGGE: Huh!

GROTH: Didn’t notice that, did you?

BAGGE: No, no, no, I wasn’t conscious of that. Well, one thing that is kind of strange, I guess, is that by and large my female characters rarely represented my “ideal.” I don’t try to draw my own masturbation fantasies.

GROTH: You deliberately avoided doing that?

BAGGE: Well, it’s like when I was an adolescent, I tried to come up with drawings that were sexy, I tried to draw sexy girls, but I would just laugh at the end result. It didn’t become a mission with me, the way it did with someone like Crumb. It just seemed like it’s so much easier to look at a dirty magazine instead. [Laughs.]

GROTH: That’s the lazy masturbator’s way out.

BAGGE: So when I draw women, I just give them the same skinny, loopy, ropy bodies that the males have, just because it’s fun to draw that. What I’m more concerned with both male and female characters is just to get the sense of movement and emotion. I would make it clear that someone like Valerie is, relatively speaking, an attractive girl, but an “attractive girl” in Baggeland, you know, that’s not saying much...

GROTH: The way you draw women, it’s hard to tell.

BAGGE: Yeah. Well, just the way she carries herself, and just certain things, the way you dress her, you can tell that she’s supposed to be the “babe.” But everybody’s so cartoony and ridiculous-looking, that I never saw much point in drawing female characters that I’m truly turned on by. Well, for one thing, my taste in women isn’t too far removed from Crumb’s. I like a “full-figured gal.” [Laughs.] But, that’s really hard to draw someone like that in my style and get a sense of movement.

But I came up with this idea, it was partly inspired by what happened with several friends of mine, both male and female, with their experiences with antidepressants. Several of them experienced rapid weight gain from them. I had a sister-in-law who went on Prozac or something, and it caused her to gain a lot of weight, and so she went off it for that reason. At the same time both her husband and son were on it, and they told me that all it did for them was give them gas! So being the sadist that I am, I had Lisa suffer all of these side effects. [Laughs.] When I had Lisa gain a certain amount of weight, at first I was thinking of it strictly on those terms, as one more wacky side effect. But then as I drew her, I thought, “oh, she looks cute this way, she’s kind or sexy this way!” So I decided to keep her that way, only have her hair grow out and dress her the way she used to dress, because I do think she looks really cute and sexy with that body. So now I am drawing my own masturbation material.

GROTH: Right! [Laughter.]

BAGGE: But it’s a lot harder to keep that sense of movement and get all the feeling and emotion out of her. You know, it’s not as expressive once I thicken up somebody. Like the guys are all skinny, too, with a few exceptions. They’re all —

GROTH: Yeah, a few exceptions. But mostly the women all have the same body types. I mean, Val and Lisa’s bodies are interchangeable.

BAGGE: Yeah. And even the men, they all have terrible posture, you know. Everybody has kind of like this S-shaped posture, and —

GROTH: That’s right, that’s right.

BAGGE: At least the females stand up straight, by and large. [Laughs.]

KIDS TODAY

GROTH: How do you feel about the contemporary cartooning scene, and specifically the current generation of cartoonists? Are you as excited about them as you were by your own—

BAGGE: By “current,” do you mean my own generation?

GROTH: I mean by way of creating an artificial demarcation between the first underground generation, and the post-underground generation, between you and the Bros. and Dan and —

BAGGE: Are you suggesting that there’s a new one that’s younger than us? Because there doesn’t seem to be a defined one.

GROTH: That’s my question.

BAGGE: There’s not a new defined one, with its own sensibility. You’d think there would be by now, but there are people — well, someone who’s very young yet very accomplished is Adrian [Tomine], and I like Adrian’s comics, but everything about him, his approach, his attitude, both artistically and even when you talk to him, you know... he’s “one of us.” He just happens to be a lot younger. But he blends right in with the whole rest of the Drawn & Quarterly stable, for the most part.

GROTH: Yeah, right, right, exactly.

BAGGE: But I can’t think of anyone else. You know, there’s some young guys who draw for — like we mentioned Jason [Lutes]. He’s also an accomplished artist, but again, there’s just nothing about his approach, or any of these young guys’ approach where I could see you draw a line, where there’s a new shift in attitude.

GROTH: That really distinguishes them from the “generation” that came up in the ’80s?

BAGGE: Correct. I don’t know if this is cause for alarm, but something that I’d been thinking of a lot lately, is that if you asked me to name my four or five absolute favorite cartoonists, I would name the same exact people now as I would ten years ago. And it’s Crumb, Dan Clowes, and the Hernandez Brothers. I still think they’re the best. They still always blow me away on a regular basis. For years they’ve been the best, and they’re always getting better. Those four consistently thrill me, every time I see something new by them. Whereas with others — Well, it isn’t like, “oh, they stink now,” there’s a lot of old favorites of mine who still do good work, but either they haven’t progressed or they’ve gone off in a direction that doesn’t do much for me.

GROTH: Do you think that’s a generational preference? Or do you think that there just have been no cartoonists coming up in the last ten years that equal the Bros. and —

BAGGE: The latter. Because Crumb and the rest of those guys aren’t even of the same generation themselves, you know. But, yeah, there’s nobody that’s around who I think could knock any of those guys off their perch. [Pause.] In a way it’s kind of sad, you know. Although I suppose that could all change in a big hurry.

GROTH: I can at least say this, emphatically, which is that there’s nobody as good as the Bros. were when they were only 22, 23, 24.

BAGGE: Yeah. Plus the fact that those guys are still my favorites is also a reflection of how determined all four of them still are to remain the best.

GROTH: I was going to say that.