Norman Keith Breyfogle was born on the 27th of February, 1960 in Iowa City, Iowa. He discovered a talent both for drawing and storytelling between the usual activities that boys got up to in the 1960s and 1970s. He always believed that these skills came from his father, who left the family when Breyfogle was young. Photos taken of Breyfogle at the age of seven show him seated on the ground, surrounded by pages of art that he drew. Such was his talent that his mother enrolled him in art classes with a local painter, Andrew Benson, who developed Breyfogle's talent to the point where local newspapers began to notice him and publish articles, and his art, as human interest stories.

Growing up he was heavily influenced by comic books, but it was Batman that enthralled him. Seeing Neal Adams work for the first time, Breyfogle was blown away. He saw what he wanted to do and who he wanted to be. He wanted to be Batman, and failing that; he would be the man who brought Batman stories to life. It is fitting that his first published work came at the age of 13 when he submitted a new costume design for Robin. It was published in Batman Family #13 (September, 1977).

Breyfogle kept drawing throughout school and college. He painted, he penciled. He created many paintings with religious themes, reflecting the struggle that he was going through finding his faith and a direction for his life. While at college he sought to learn, to open his mind and become enlightened with the help of psychedelics and the writings of Carlos Casteneda. Breyfogle always said that although he found what he was looking for, he never stopped seeking out higher planes. (He would return to this quest in 1995, in his most personal work, the six issue series Metaphysique, which he wrote and drew for Malibu.)

Breyfogle kept drawing throughout school and college. He painted, he penciled. He created many paintings with religious themes, reflecting the struggle that he was going through finding his faith and a direction for his life. While at college he sought to learn, to open his mind and become enlightened with the help of psychedelics and the writings of Carlos Casteneda. Breyfogle always said that although he found what he was looking for, he never stopped seeking out higher planes. (He would return to this quest in 1995, in his most personal work, the six issue series Metaphysique, which he wrote and drew for Malibu.)

At the age of 17 Breyfogle was asked to write and draw a full blown comic book, titled Tech Team for the College Of Michigan. This led to Breyfogle enrolling at the Northern Michigan University where he majored in both painting and illustration. Graduating in 1982, Breyfogle moved to California and attended his first San Diego Comic Book Convention where he participated in Sal Amendola’s New Talent Showcase program, and his first professionally published work for DC was subsequently published in issues #11 and #13. At San Diego he was approached by art agent Mike Friedrich, who, via his Star*Reach imprint, was more than happy to sign the young artist to an exclusive contract.

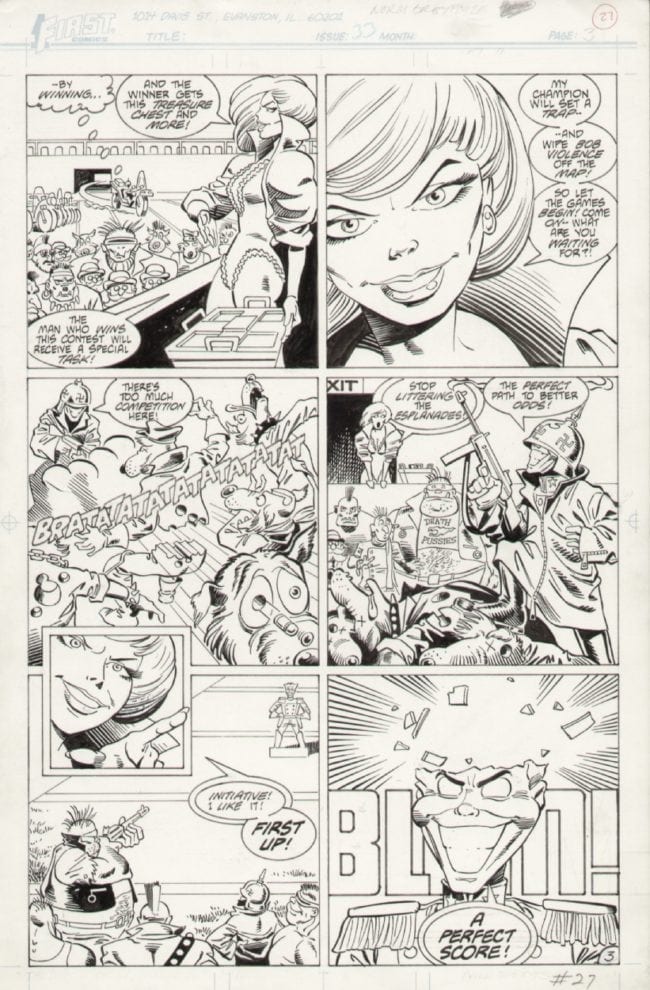

Friedrich was able to secure Breyfogle his first major comic book work drawing Bob Violence, then a back-up series in Howard Chaykin’s American Flagg (published by First Comics). While Bob Violence wasn’t a regular gig (some stories were drawn by Joe Staton), it did mark Breyfogle's breakthrough. During that period he also sought work as a draftsman and was able to hone his technical skills by illustrating mechanical items for organizations such as NASA, where he provided technical drawings of the Space Shuttle.

Breyfogle’s work on Bob Violence didn’t escape notice and he was soon tapped to become an artist on First Comics’ Whisper, written by Steven Grant, and described by Breyfogle at the time as being, “political drama with a lot of sleaze.” Breyfogle soon found himself penciling, inking, lettering and hand painting the covers. Breyfogle had also managed to pencil a Legion of Superheroes back-up story and sold Marvel a Captain America story he wrote, penciled, inked and lettered, which subsequently appeared in Marvel Fanfare. Marvel Fanfare was, at that stage, a title that showcased inventory stories, new talent and stories by creators who enjoyed a very flexible deadline. Of interest is that Breyfogle’s Captain America story began life as a Batman story--and when DC passed on it Breyfogle merely cut the Batman images out and replaced them with freshly drawn Captain America figures.

Breyfogle’s work on Bob Violence didn’t escape notice and he was soon tapped to become an artist on First Comics’ Whisper, written by Steven Grant, and described by Breyfogle at the time as being, “political drama with a lot of sleaze.” Breyfogle soon found himself penciling, inking, lettering and hand painting the covers. Breyfogle had also managed to pencil a Legion of Superheroes back-up story and sold Marvel a Captain America story he wrote, penciled, inked and lettered, which subsequently appeared in Marvel Fanfare. Marvel Fanfare was, at that stage, a title that showcased inventory stories, new talent and stories by creators who enjoyed a very flexible deadline. Of interest is that Breyfogle’s Captain America story began life as a Batman story--and when DC passed on it Breyfogle merely cut the Batman images out and replaced them with freshly drawn Captain America figures.

Two issues after his Captain America story, Breyfogle was able to land another back-up feature in Marvel Fanfare, this time showcasing the Fantastic Four and drawn in a style very reminiscent of John Byrne and Jerry Ordway, both of whom were the current art team for the Fantastic Four at the time.

His work at Marvel, First Comics, and New Talent Showcase led to DC hiring Breyfogle to draw an issue of Tales of The Legion Of Superheroes, followed by his first professional Batman work (albeit a solo Robin story), Batman Annual #11. Breyfogle expressed his strong desire to draw Batman to Mike Friedrich, who, using his contacts at DC, managed to get him attached to Detective Comics, beginning as the fill-in artist with issue #579, cover dated October 1987. At the same time Breyfogle was still the regular artist on Whisper and would draw another three issues of that title in conjunction to his DC work.

At the time Detective Comics, and Batman in general, was experiencing a resurgence due to the efforts of Frank Miller and his Dark Knight Returns and Batman: Year One series and film director Tim Burton, who was soon to reimagine the character in the 1989 motion picture. Both Miller and Burton, with later contributions from Batman writers Max Allen Collins, Jim Starlin and Mike W Barr, discarded the (public) camp image that Batman had been saddled with since the ‘60s and turned to a darker vision, updating the character as a grim, hardboiled character, which suited Breyfogle’s artwork perfectly. Detective Comics was riding a wave of popularity and had seen a combination of new and legendary artists working on the title, including Gene Colan, Don Newton, Klaus Janson, Dick Giordano, Pat Broderick, Alan Davis, and Jim Aparo.

At the time Detective Comics, and Batman in general, was experiencing a resurgence due to the efforts of Frank Miller and his Dark Knight Returns and Batman: Year One series and film director Tim Burton, who was soon to reimagine the character in the 1989 motion picture. Both Miller and Burton, with later contributions from Batman writers Max Allen Collins, Jim Starlin and Mike W Barr, discarded the (public) camp image that Batman had been saddled with since the ‘60s and turned to a darker vision, updating the character as a grim, hardboiled character, which suited Breyfogle’s artwork perfectly. Detective Comics was riding a wave of popularity and had seen a combination of new and legendary artists working on the title, including Gene Colan, Don Newton, Klaus Janson, Dick Giordano, Pat Broderick, Alan Davis, and Jim Aparo.

Immediately preceding Breyfogle’s entry on Detective Comics was the Batman: Year Two story arc, a sequel to Miller’s Batman: Year One, written by Mike W Barr and featuring the artistic talents of Alan Davis, Paul Neary, Pablo Marcos, as well as an emerging Todd McFarlane. The time couldn’t have been better for Breyfogle to come onto the title. After working with writers Barr and Jo Duffy, Breyfogle was teamed up with two British writers, John Wagner and Alan Grant, fresh from 2000AD's Judge Dredd. While Wagner soon dropped out, Breyfogle formed a solid partnership with Grant, and a friendship based upon mutual respect and admiration that continues to this day, and the two created one of the most fondly remembered runs on the title in recent memory.

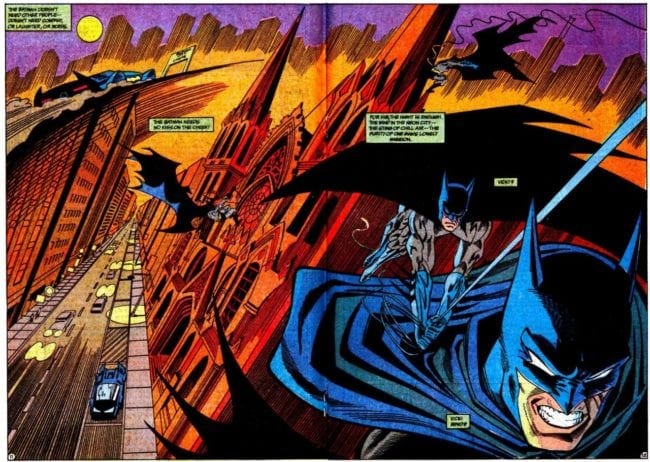

Working in close tandem with fellow writers Dough Moench and Marv Wolfman, Grant defined Batman throughout the late 1980s and 1990s. Grant’s writing style was straight forward and confrontational, with an emphasis on reality, as opposed to mainstream superhero and unrealistic storylines. Drawing these Batman stories in the pages of both Detective Comics and Batman saw Breyfogle came to the fore as an artist and as a professional. He soon became a fan favorite and, encouraged by Denny O’Neill and inspired by the quality of Grant’s writing, Breyfogle left behind the ‘traditional’ Batman look and began to stamp his own unique style onto the character and books, much in the same manner as artists such as Neal Adams and Trevor Von Eeden had done before him. His expressionistic style meshed perfectly with Alan Grant's scripts and when the pair was joined by inker Steve Mitchell, solid inks allowed Breyfogle's style to fully develop. Breyfogle's unique use of angles and shadows was a breath of fresh air, harkening back more to the days of Gene Colan more than it crisp, clean linework of Jim Aparo and Alan Davis.

Working in close tandem with fellow writers Dough Moench and Marv Wolfman, Grant defined Batman throughout the late 1980s and 1990s. Grant’s writing style was straight forward and confrontational, with an emphasis on reality, as opposed to mainstream superhero and unrealistic storylines. Drawing these Batman stories in the pages of both Detective Comics and Batman saw Breyfogle came to the fore as an artist and as a professional. He soon became a fan favorite and, encouraged by Denny O’Neill and inspired by the quality of Grant’s writing, Breyfogle left behind the ‘traditional’ Batman look and began to stamp his own unique style onto the character and books, much in the same manner as artists such as Neal Adams and Trevor Von Eeden had done before him. His expressionistic style meshed perfectly with Alan Grant's scripts and when the pair was joined by inker Steve Mitchell, solid inks allowed Breyfogle's style to fully develop. Breyfogle's unique use of angles and shadows was a breath of fresh air, harkening back more to the days of Gene Colan more than it crisp, clean linework of Jim Aparo and Alan Davis.

Inker Steve Mitchell was Breyfogle's assigned inker after some mixed results on his early Batman issues, which saw him inked by both Pablo Marcos and Kim DeMulder. At that point in time Mitchell was considered to be an industry veteran, even though he was only a few years older than Breyfogle. Mitchell had broken into comics by inking Gil Kane at Marvel before working with Neal Adams and Dick Giordano at Continuity Studios and becoming one of the legendary Crusty Bunkers. During the ‘70s and ‘80s Mitchell would become an inker in demand, always able to hit his deadlines, and, more importantly, his style complimented the penciler without overpowering what was on the page. In this regard he was an excellent fit for an emerging artist such as Norm Breyfogle. Other than one issue inked by Tim Sale and another inked by Dick Giordano, Mitchell would ink almost all of Breyfogle's late ‘80s and early ‘90s Batman work, with the exceptions being issues that Breyfogle inked himself.

Inker Steve Mitchell was Breyfogle's assigned inker after some mixed results on his early Batman issues, which saw him inked by both Pablo Marcos and Kim DeMulder. At that point in time Mitchell was considered to be an industry veteran, even though he was only a few years older than Breyfogle. Mitchell had broken into comics by inking Gil Kane at Marvel before working with Neal Adams and Dick Giordano at Continuity Studios and becoming one of the legendary Crusty Bunkers. During the ‘70s and ‘80s Mitchell would become an inker in demand, always able to hit his deadlines, and, more importantly, his style complimented the penciler without overpowering what was on the page. In this regard he was an excellent fit for an emerging artist such as Norm Breyfogle. Other than one issue inked by Tim Sale and another inked by Dick Giordano, Mitchell would ink almost all of Breyfogle's late ‘80s and early ‘90s Batman work, with the exceptions being issues that Breyfogle inked himself.

Alan Grant would later recall:

When a writer and artist hit it off, like Wagner and Ezquerra, they add a dimension to stories nobody put there before. Some kind of synergy shines through. You can see it in nearly everything John's worked on with Carlos. All the important characters John's created, I'd say, were done with Carlos. I felt the same about Breyfogle - Norm was my Carlos and I was his Wagner!

My work either stands up on its own or falls down, I can't justify or argue for it. But those Batmans, it was fucking cracking stuff! No wonder the Americans went crazy for it. They were used to Batman fighting jelly monsters from space, the character being treated like some kind of soap opera. That wasn't my idea of Batman, what he should be. Norm and I redefined Batman, made him what we wanted the character to be. We had a brilliant run. I re-read all the letters pages, to make sure it wasn't just me who felt the material was that good. The letters pages were just the same. It wasn't all down to me; it was Norm's art as well. I'd say Breyfogle's four years on Batman are better than anything anybody's done since. I'm not saying there aren't better individual stories. Bolland will illustrate a story like The Killing Joke, or Kelley Jones will do a great Batman tale. But for consistent month-in, month-out brilliance, no one touches Norm.

There were several highlights of the Grant-Breyfogle run, including Breyfogle providing cover art for Batman #474, over a background provided by master designer Anton Furst, who created the memorable Gotham City visuals for the first Burton Batman movie, and the introduction of the new Robin, Timothy Drake, in a costume designed by Neal Adams in Batman #465. A three-part story involving the Jack Kirby creation The Demon was another highlight that both Breyfogle and Grant have referred to it as being the high watermark of their Batman output. Several of the characters and concepts developed by Grant and Breyfogle would be revisited by subsequent creative teams in the future, with Jeph Loeb and Jim Lee recycling the duo’s concepts in their critically acclaimed ‘Hush’ series (notable the use of the deceased Robin, Jason Todd, being revealed as Clayface), as well as Frank Miller who, in the mid 2000s, announced an idea for a story whereby Batman would begin to hunt down terrorists, a concept that Grant and Breyfogle had done as early as 1988 with "An American Batman in London".

There were several highlights of the Grant-Breyfogle run, including Breyfogle providing cover art for Batman #474, over a background provided by master designer Anton Furst, who created the memorable Gotham City visuals for the first Burton Batman movie, and the introduction of the new Robin, Timothy Drake, in a costume designed by Neal Adams in Batman #465. A three-part story involving the Jack Kirby creation The Demon was another highlight that both Breyfogle and Grant have referred to it as being the high watermark of their Batman output. Several of the characters and concepts developed by Grant and Breyfogle would be revisited by subsequent creative teams in the future, with Jeph Loeb and Jim Lee recycling the duo’s concepts in their critically acclaimed ‘Hush’ series (notable the use of the deceased Robin, Jason Todd, being revealed as Clayface), as well as Frank Miller who, in the mid 2000s, announced an idea for a story whereby Batman would begin to hunt down terrorists, a concept that Grant and Breyfogle had done as early as 1988 with "An American Batman in London".

Interestingly the pair began their run with a storyline that introduced the Ventriloquist and Scarface, in Detective Comics #584 in February 1988, and they ended their regular Batman run, in Batman #477, in April 1992, with a story involving the Ventriloquist and Scarface. Other characters created by the duo included the Ratcatcher, the Corrosive Man, Mortimer Kadaver, Corenelius Stirk, aka The Fear, Joe Potato, the Obeah Man, the new Clayfaces and Maxie Zeus. Once the duo crossed over to the Shadow Of The Bat title they once again created two more memorable characters in the form of the serial killer Zsasz, who was featured, albeit in a small role, in the movie Batman Begins and the warden of Arkham Asylum, Jeremiah Arkham. But their most famous creation, and the one that they loved above all else, was Anarky.

Originally created as an answer to Alan Moore’s V For Vendetta, Grant and Breyfogle took the character to places where Moore’s V had never been. As the pair developed stories, they developed Anarky. He grew at the same time, to adapt, to the new worlds that he was going into. From his beginnings as a teenage anarchist, Anarky eventually became a Green Lantern, battled Darkside and The Demon and, in a story all but ignored by DC, was revealed as being the son of the Joker.

Originally created as an answer to Alan Moore’s V For Vendetta, Grant and Breyfogle took the character to places where Moore’s V had never been. As the pair developed stories, they developed Anarky. He grew at the same time, to adapt, to the new worlds that he was going into. From his beginnings as a teenage anarchist, Anarky eventually became a Green Lantern, battled Darkside and The Demon and, in a story all but ignored by DC, was revealed as being the son of the Joker.

Grant and Breyfogle would be moved from Detective Comics and placed on the titular Batman book, and would be further rewarded by DC with the creation of a new title, Batman: Shadow Of The Bat, which was established for Alan Grant and Norm Breyfogle to explore further concepts. Breyfogle would only stay on the newly launched title for a short run as he continued to push the boundaries of what he wanted to do in comic books, but not before working with Grant to create "The Last Arkham", a groundbreaking story which saw the character of Batman locked up in Arkham Aslyum as a criminal. However satisfied Breyfogle was drawing the character he felt born to draw, he continued to explore his options by working at other companies.

In late 1992 Breyfogle ran the idea of branching out by Mike Friedrich and asked him to sound out potential publishers. In due course he found himself considering two serious offers for his services. The first came from the newly formed Image Comics. Image, formed by Jim Lee, Todd McFarlane, Erik Larsen, Rob Liefeld, Jim Valentino, and Marc Silvestri, were approaching the ‘hot’ artists of the time at both Marvel and DC with a view of poaching talent. The carrot on the stick was the opportunity to work on their own creator owned and developed concepts, and in this way they attracted both emerging and established artists such as Sam Kieth, Whilce Portacio, Jae Lee, Dale Keown, Keith Giffen, Jerry Ordway, J. Scott Campbell, Stephen Platt, and several others. Breyfogle and longtime Spider-Man artist Mark Bagley were amongst the very few who declined the invite.

The other offer for Breyfogle’s services came from the then publisher of Image, Malibu. Scott Rosenberg, the owner of Malibu, was unique in that he didn’t use ownership as an incentive to lure some of the top talent of the day. Dubbed the Ultraverse, Malibu owned the characters and concepts, yet the creators would receive a royalty from any future sales of the titles, even those that they were not working on.

The other offer for Breyfogle’s services came from the then publisher of Image, Malibu. Scott Rosenberg, the owner of Malibu, was unique in that he didn’t use ownership as an incentive to lure some of the top talent of the day. Dubbed the Ultraverse, Malibu owned the characters and concepts, yet the creators would receive a royalty from any future sales of the titles, even those that they were not working on.

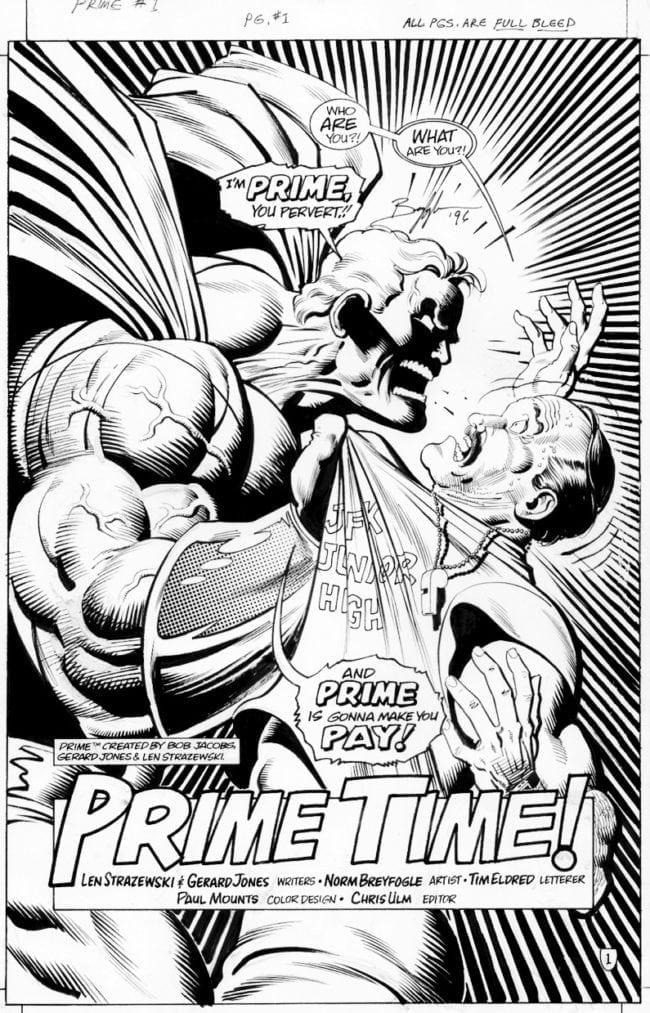

By offering such incentives, Rosenberg was able to lure Breyfogle away from DC and Batman. At the time Breyfogle was interested in expanding his horizons and exploring his own concept, Metaphysique. Metaphysique had first seen print as a two issue mini-series published by Eclipse in the 1991, but the concept that Breyfogle now wished to explore was a highly personal storyline, combining heroism, science fiction, lucid dreaming and mysticism in a storyline that foreshadowed The Matrix, but explored similar concepts. The incentives used to get Breyfogle to Malibu included a healthy signing fee, the opportunity to publish Metaphysique, sight unseen, full ownership of Metaphysique and part ownership in an already released character, Prime--a super-hero charaacter created by by Len Strazewski, Gerard Jones, Bret Blevins (who created the costume) and Malibu President Bob Jacob and visually realized by Breyfogle. (Metaphysique would be published on Malibu’s Bravura line, which was established to publish creator owned material.) Breyfogle discussed the offer with Denny O’Neil, who, understanding the magnitude of the offer, gave his blessing for the move.

A third publisher, Now Comics, was also vying for Breyfogle’s services. Initially reluctant to accept any new projects due to his workload, Breyfogle reconsidered when the page rate was increased to a point where he couldn’t say no. The newly launched Mr T title, based on the over the top real life actor, would feature Breyfogle’s interior art with a combination of Neal Adams covers and fully painted covers by Breyfogle. Unfortunately for Mr T and Now Comics, the comic wasn’t the raging success that they had expected it to be and the comic was cancelled after a handful of issues. Luckily Breyfogle had more than enough work at Malibu with both Prime and Metaphysique to occupy his time.

A third publisher, Now Comics, was also vying for Breyfogle’s services. Initially reluctant to accept any new projects due to his workload, Breyfogle reconsidered when the page rate was increased to a point where he couldn’t say no. The newly launched Mr T title, based on the over the top real life actor, would feature Breyfogle’s interior art with a combination of Neal Adams covers and fully painted covers by Breyfogle. Unfortunately for Mr T and Now Comics, the comic wasn’t the raging success that they had expected it to be and the comic was cancelled after a handful of issues. Luckily Breyfogle had more than enough work at Malibu with both Prime and Metaphysique to occupy his time.

After twelve issues of Prime and six issues of Metaphysique, his Malibu obligations were completed and Breyfogle sought employment elsewhere. He found himself at Valiant/Acclaim where he was assigned the book Bloodshot. Breyfogle wasn’t happy working on Bloodshot, but people would never know. No matter the job, Breyfogle's artwork was always of the highest quality. Even when he loathed the script, the story and the character, even when the money was virtually non-existent, the art didn’t suffer.

Once Brefyogle finished with Acclaim he returned to DC, reuniting with Alan Grant for the 50th issue of Batman: Shadow Of The Bat. The reunion was further extended when DC commissioned a four part mini-series featuring Anarky, the character that Grant and Breyfogle had created and introduced in Detective Comics. The series was successful enough for DC to further commission a regular, on-going series from the pair. Sadly the series wasn’t a lasting success. Beginning in May 1999, the series lasted a mere eight issues and was cancelled by December 1999. A further two issues were scripted and penciled, but these remain unpublished by DC.

While at DC, Breyfogle worked on titles as diverse as Hawkman, Lobo, Superman, Wonder Woman and Catwoman. The latter two were of particular interest as Breygofle inked industry legend Dave Cockrum on one of his last comic book related jobs, and also inked artist Jim Balent on Balent’s signature DC title, Catwoman. Breyfogle also penciled the three issue Elseworlds series, Flashpoint, an alternate telling of the story of The Flash and this, as well as Green Lantern: Circle of Fire, leading up to an original idea featuring Batman with Alan Grant attached as co-collaborator which was soon published under the title Batman: Dreamland. Sadly this one shot would mark the last time that Breyfogle drew the character that made him famous in a sole book, with the exception being Batman featured as a supporting character in a Green Lantern tribute to the Julie Schwartz issue in 2004. Breyfogle was fortunate enough to work with yet more visionary writers, notably Rick Viech on Aquaman and J.M. Dematties on The Spectre, as well as Alan Grant, during this second stint at DC.

While at DC, Breyfogle worked on titles as diverse as Hawkman, Lobo, Superman, Wonder Woman and Catwoman. The latter two were of particular interest as Breygofle inked industry legend Dave Cockrum on one of his last comic book related jobs, and also inked artist Jim Balent on Balent’s signature DC title, Catwoman. Breyfogle also penciled the three issue Elseworlds series, Flashpoint, an alternate telling of the story of The Flash and this, as well as Green Lantern: Circle of Fire, leading up to an original idea featuring Batman with Alan Grant attached as co-collaborator which was soon published under the title Batman: Dreamland. Sadly this one shot would mark the last time that Breyfogle drew the character that made him famous in a sole book, with the exception being Batman featured as a supporting character in a Green Lantern tribute to the Julie Schwartz issue in 2004. Breyfogle was fortunate enough to work with yet more visionary writers, notably Rick Viech on Aquaman and J.M. Dematties on The Spectre, as well as Alan Grant, during this second stint at DC.

Once his work on The Spectre was finished, work dried up. Breyfogle, who was always open about his opinions, believed that the lack of work was due to ageism and he wrote about this in the Comic Buyers Guide. Unfortunately for Breyfogle, this letter saw him branded as unstable by some editors at both DC and Marvel. When jobs arrived, Breyfogle was always gracious, always delivered the work before the deadline and always delivered the same high quality art. He fully embraced the internet, and Facebook. He could speak directly to his fans and would engage in deep philosophical discussions on any topic under the sun with people he would never meet. Such was his nature that he accepted people as his friend until they failed to pay him for work, slighted him or his close friends or managed to anger him. Even then he’d give them a second chance and as mad as he’d get, his good humor was never far away.

By the mid-2000s his personal life found some stability and he began to write his memoirs. Despite this his professional life was becoming more complicated. Eager to continue working and with bills to pay, Breyfogle accepted assignments from many small press publishers. Working on books such as Black Tide, Of Bitter Souls, and Dangers Dozen ensured that he was still in front of the public. He also accepted commissions, again delivering high standard work for many happy fans.

Breyfogle’s lean years came to an end when Archie approached him and he was hired to work on a new title, Life With Archie. The thought of Norm Breyfogle, the Batman artist of the 1990s, drawing Archie might have sounded wrong to some, Bryefogle was adaptable and he delivered. At the same time, he delved into the world of commercial art, expressing surprise at the rates he was being paid for what he considered to be such little work. While lucrative, the commercial art bored him, so he left it behind.

Breyfogle’s lean years came to an end when Archie approached him and he was hired to work on a new title, Life With Archie. The thought of Norm Breyfogle, the Batman artist of the 1990s, drawing Archie might have sounded wrong to some, Bryefogle was adaptable and he delivered. At the same time, he delved into the world of commercial art, expressing surprise at the rates he was being paid for what he considered to be such little work. While lucrative, the commercial art bored him, so he left it behind.

It was DC where he ended up, yet again. Announcing their DC Retroactive titles, Alan Grant and Norm Breyfogle were tapped to provide the 1990s version of Batman. This would mark the last collaboration between the pair. The response to Batman Retroactive led to Breyfogle being offered the art duties on Batman Beyond, something he took up with glee. Breyfogle was happy. Sadly it wouldn’t last.

Just as Breyfogle was in the best shape of his life, both professionally and personally, things fell apart, again. Breyfogle was replaced on Batman Beyond. Breyfogle felt it was, again, personal, although he was told it wasn’t. Work was coming in though, and Breyfogle was asked to pair up again with Alan Grant, this time on a Judge Dredd story.

Breyfogle always had a temper. He was passionate about social justice and hated the way the Right would look down upon the Left, and the poor, with disdain and disgust. Breyfogle would engage in debate with anyone and everyone, debates that turned into on-line fights. Breyfogle couldn’t allow anyone to get the last word and it was one night when, while arguing yet again, he smashed his fist into his computer monitor. Instantly he felt a searing jolt up his arm and believed he’d been electrocuted. He could barely move and speak. He managed to call for an ambulance and was taken to the hospital where it was discovered that he’d suffered a serious stroke. Only the fact that he was in peak physical condition had saved him from being a fatality. But survival came at a cost – his left side was now paralyzed.

Breyfogle was left-handed. He would never draw again. For Breyfogle, his artistic life ended there. In hospital with his savings being eaten away, he reached out and a fundraiser was established. Breyfogle, who now found it hard to speak to anyone without crying, wept when he discovered the identities of those who had dug deep, including DC Comics. He felt he wasn’t worthy of such assistance, especially as he knew he would never be able to repay people. He wouldn’t accept that he’d more than earned any help with all of the people he’d helped.

Breyfogle struggled to cope with the effects of the stroke, particularly the paralysis of his drawing hand. He kept engaging with his followers and fans on Facebook and enjoyed talking to them. Eventually the stroke finished its job and Breyfogle’s heart gave out.

Breyfogle was cremated on September 30, and there will be a celebration of his life on October 27 from 1 to 3 p.m. at Ericson Crowley Peterson Funeral Home in Calumet, Michigan.