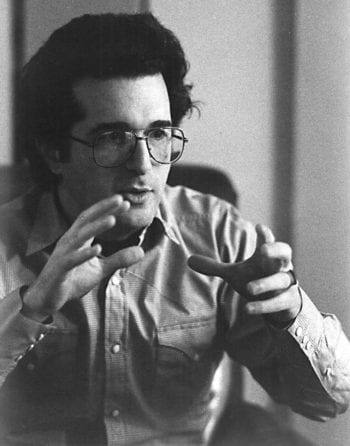

Michael Lawrence Fleisher, an often controversial and polarizing comic-book and comic-strip writer, died February 2, 2018, from complications of Alzheimer’s disease in Beaverton, Oregon, according to his half brother, Martin Fleisher. He was 75.

Fleisher is perhaps best remembered in comics for his groundbreaking work at DC Comics on The Spectre and Jonah Hex, the authorized encyclopedias he wrote on Superman, Batman, and Wonder Woman, and a libel case he doggedly pursued and lost against The Comics Journal (Fantagraphics, Inc.), Journal editor Gary Groth, and the science fiction writer Harlan Ellison.

Though comics would dominate the first part of his professional career, in later life Fleisher proved himself to be a dedicated researcher, scholar, and humanitarian.

Born November 1, 1942 in New York City to David Fleisher (later chairman of the department of English and fine arts at Yeshiva University) and Nell (Blaustein) Fleisher Moskowitz, he graduated from the Horace Mann School for Boys, an exclusive college preparatory school in the Bronx, in 1960.

His parents divorced when he was four years old and, thereafter, Fleisher said his father would take him to watch double features in New York City on Saturdays, where he developed a love for Westerns. His favorites starred Randolph Scott. In the 1960s, he enjoyed the so-called “Spaghetti Westerns” starring Clint Eastwood. “So it wasn’t very hard [for me] to write [Westerns] at all,” he said in a 2010 interview.

And he read comics. From 1948 to 1956, he read and collected not only Westerns but every comic that featured Superman, Superboy, and, especially, Batman. EC Comics, though, he said, “used to frighten me” and though he read an occasional issue, he mostly shied away from them.

At fourteen, Fleisher sold off his comics collection for a penny apiece (“I made about $22.”) and set his sights on becoming a novelist. He attended the University of Chicago from 1960 to 1961 where his writing was rejected by the University’s literary magazines, and he was unable to get into an advanced creative writing course.

He remained in Chicago for most of the 1960s and worked for an insurance brokerage. In March 1962, he married Joy Phinizy. They divorced in June 1965. He said that he abruptly quit his insurance job and hitchhiked to Mexico in 1966 “with my dog and a pack and portable tape recorder,” traveling about 10,000 miles in all. “I stayed there a year, and I vowed that I would never work again except as a writer,” he told The Comics Journal in 1980.

He said he became involved in the civil rights and anti-Vietnam War movements and was among the demonstrators at the August 1968 Democratic National Convention. The following month he returned to New York where, by early 1969, he had a job writing and editing for Encyclopedia Britannica.

The Encyclopedia of Comic Book Heroes

While at Britannica, an idea that started as a joke by a co-worker led him to a seven-year odyssey — researching and writing The Encyclopedia of Comic Book Heroes, which details the adventures of various comic book heroes, story by story. He sold the idea to a book publisher and then got permission from DC, Marvel, Fawcett, and Will Eisner to comb through their archives. He filled in the gaps by tapping into the comics-collecting community, paying $5 each to borrow the 1,000 issues he estimated he needed.

He began with his childhood favorite, Batman, followed by Wonder Woman and Superman, the three heroes with the longest histories. As individual volumes, they originally saw print from 1976 to 1978. In interviews, Fleisher would often drop the tantalizing tidbit that he’d actually written (and still possessed) manuscripts for additional volumes covering Captain America, Captain Marvel, Doctor Fate, The Flash (Golden and Silver Age versions), Green Lantern (Golden and Silver Age), Hawkman (Golden and Silver Age), The Hulk, The Human Torch, Iron Man, Plastic Man, The Spectre, The Spirit, Starman, and the Sub-Mariner. Additionally, he said, he had notes on The Fantastic Four and Spider-Man. In all, he said he wrote over two million words and that the three volumes that saw print comprised only half of his work on the project.

DC editor Joe Orlando hired him as his assistant and paired Fleisher with a number of writers to prepare scripts and learn the trade. Orlando’s goal was to recreate a version of the horror comics line that EC Comics had pioneered two decades earlier (for which Orlando had been an artist) before the Comics Code Authority was introduced. DC called those comics its “mystery” or “weird” titles.

In his beginning years as a comics writer, Fleisher usually co-wrote his scripts with others. His earliest comic book scripting credit is for dialogue on “Kiss of the Serpent”, a story plotted by Mary DeZuniga, published in DC’s Sinister House of Secret Love #4, April-May 1972. He shared a writing credit with Lynn Marron on “Death at Castle Dunbar” in the following issue, when the title changed to Secrets of Sinister House. There followed collaborations with Maxene Fabe and Russell Carley on other stories for DC’s Orlando-edited titles.

He helped close out the original run of the syndicated Little Orphan Annie newspaper strip for the Tribune News Syndicate by co-scripting with Orlando the story that ran from August 20, 1973 to early February 1974. (The strip went into reprints in April of that year; new stories didn’t begin again until December 1979.) The story is notable for featuring a magical being who meted out a milder version of the type of lethal punishment that Fleisher’s Spectre would become infamous for.

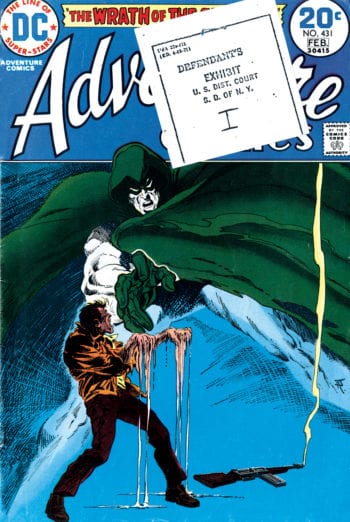

The Spectre

The first of an initial ten Spectre stories by Fleisher and artist Jim Aparo debuted in Adventure Comics #431, January-February 1974, and was met with both praise and criticism from readers for the gruesome methods — all of which were approved by the Comics Code — that Fleisher devised for The Spectre to dispatch the villains.

The Spectre, created by Jerry Siegel and Bernard Baily in 1940, was notable in the character’s original run for imposing violent retribution against evildoers, and Fleisher unabashedly copied from it. In Siegel and Baily’s first story, Jim Corrigan, upon being introduced, is immediately killed by being encased in cement and thrown into a river. A God-like figure intervenes and returns Corrigan to Earth to combat evil as The Spectre. In that first outing, The Spectre uses the power of his mind to skin an assassin alive, leaving only a skeleton. Fleisher used the same method of punishment in his first Spectre story.

In other instances, Fleisher and Aparo’s Spectre had bad guys snipped in half by giant scissors, turned into wood and sliced into sections by a buzzsaw, turned into wax and melted, and turned into glass and shattered.

But after twenty years under a strict Comics Code, fans, critics, and even others at DC were unprepared, and some reacted harshly. The series was abruptly canceled with Adventure Comics #440, July-August 1975, with two of Fleisher’s scripts left undrawn. Aparo illustrated the remaining scripts thirteen years later, and they were published in The Wrath of the Spectre #4, August 1988.

Jonah Hex and Other Work

Fleisher took over the Jonah Hex series, which he considered his best work in comics, with Weird Western Tales #22 (May-June 1974). Hex was a ruthless but honorable bounty hunter in the Old West with one half of his face heavily scarred. Created by writer John Albano, the character was fleshed out by Fleisher for the next dozen years to rave reviews. Fleisher’s most famous Jonah Hex story, and one of his favorites, was “The Last Bounty Hunter”, in Jonah Hex Spectacular, Fall 1978, in which the 66-year-old Jonah Hex is murdered by shotgun at point-blank range. His body is then stuffed, mounted, and turned into a sideshow attraction at a Wild West show. The story was nominated for a British Eagle Award in 1979.

Fleisher’s other work for DC included creating and writing Scalphunter (which he said was his least favorite Western assignment), and producing scripts for The Creeper, Sandman (with Jack Kirby), and Shade, The Changing Man (with Steve Ditko).

In that 2010 interview, reflecting upon his career, Fleisher said, “I was a bad superhero writer. … I always felt awkward with superheroes.” But in 1981, he wrote a few Batman stories for DC in which he reintroduced the Crime Doctor (a villain not seen for 37 years), co-created the Electrocutioner, and created a bit of comics lore by writing the long overdue origin of the Penguin.

For the short-lived 1970s Atlas line of comics, he wrote The Brute, The Grim Ghost, Morlock 2001, Ironjaw, and The Tarantula.

He wrote for Marvel from 1979 to 1989, including stints on Ghost Rider, Man-Thing, Spider-Woman, and Conan. He also wrote a number of stories for Warren Publications, including another of his favorites, “Night of the Chicken” (Vampirella #71, August 1978), about a farmer with a fetish for dressing up women like chickens only to brutally murder them and grind up their bodies for chicken feed.

He seemed to have penchant for “Night” titles, including “The Night of the Teddy Bear!” (House of Mystery #222), “Night of the Brute” (The Brute #1), “Night of the Squid” (Vampirella #79), “Night of the Rat!” (The Savage Sword of Conan #95), and “Night of the Bat” (Hex #11), among others.

When DC discontinued Jonah Hex as a casualty of its Crisis on Infinite Earths miniseries in 1985, Fleisher took his hero, without explanation, into a future post-apocalyptic world. That series, titled simply Hex, was said to have been more popular overseas than in the U.S. It ran eighteen issues.

With the demise of Hex and his Conan assignment at Marvel, Fleisher turned to Fleetway Comics in the United Kingdom and wrote two series for 2000 AD in the early 1990s, Harlem Heroes and Rogue Trooper. His last published story was the Rogue Trooper story “The Arena of Long Knives” in Fleetway’s 2000 AD Yearbook for 1992.

A Novel and a Lawsuit

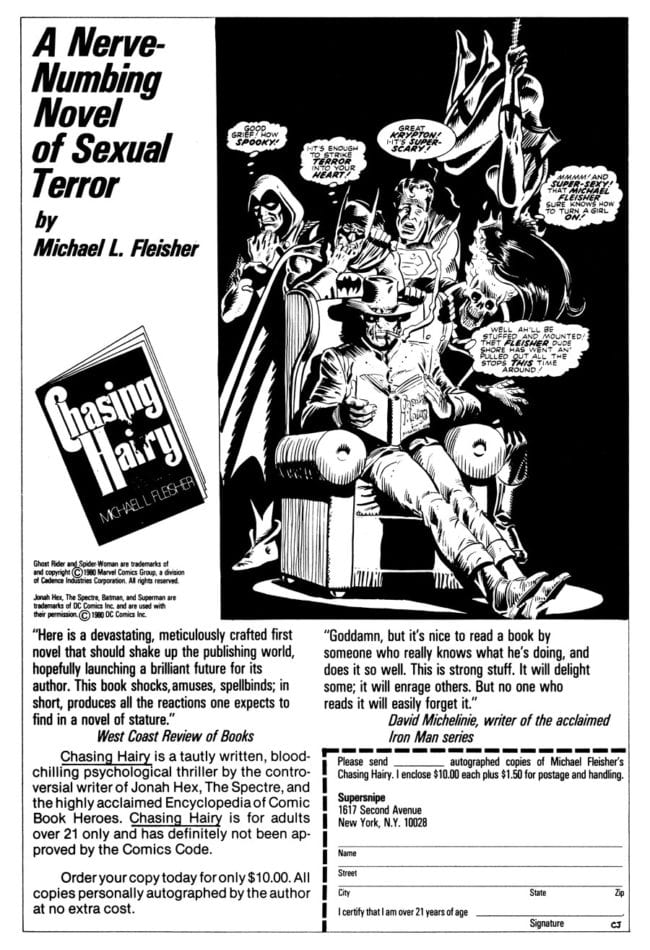

In 1979, St. Martin’s Press published Fleisher’s first novel, Chasing Hairy, billed on the cover as a "novel of sexual terror” and described by its publisher as “a brutal, profoundly disturbing portrait of two young men” whose friendship is based on “the shared but unconscious hostility they bear towards women.”

In an attempt to publicize the book, Fleisher requested an interview with The Comics Journal and arranged for an ad to run in its pages featuring several of the DC and Marvel characters that he had written endorsing him and his book.

Prior to Fleisher’s interview, however, The Comics Journal published, in February 1980, an interview with science fiction writer Harlan Ellison in which Ellison, in an attempt to praise Fleisher for his writing, compared him to the artist H.R. Giger and the writer Robert E. Howard. Ellison called Fleisher “a genuine twisted mentality,” “fascinating,” and “probably the only one writing who is interesting.” Among the other words Ellison employed were “certifiable,” “derange-o,” “bugfuck,” and “lunatic.”

Fleisher objected to Ellison’s characterization. After his own interview appeared in The Comics Journal in June, Fleisher demanded an apology and a retraction, which he wrote, and which the Journal refused to print. He filed suit for $2 million in Federal District Court in New York on October 7, 1980, naming Fantagraphics, Gary Groth, and Ellison as defendants.

Opinions for and against Fleisher and his claims divided the comics community. The case was closely watched and people chose sides. Feelings ran high.

Following more than six years of pretrial motions, maneuverings, discovery, and depositions (Fleisher’s deposition ran to 1,100 pages), the trial finally began on November 10, 1986. Groth, Ellison, and Fleisher spent extensive amounts of time on the witness stand.

On December 5, after four weeks of testimony, the case went to the jury. The eight-member panel deliberated for less than an hour and a half and returned its verdict in favor of the defendants. Fleisher had lost.

After Comics

During his prolific writing career, Fleisher managed to travel extensively, and he became interested in foreign cultures. A trip to New Guinea in 1984 inspired him to enroll in an undergraduate program in anthropology at The School of General Studies of Columbia University, where he earned a Bachelor’s degree and graduated summa cum laude in 1991.

After graduation, he moved to Ann Arbor, Michigan, where he enrolled in graduate studies at the University of Michigan and left comics behind him. He studied the phenomenon of the theft of cattle in Tanzania for sale in neighboring Kenya. He spent two years in Tanzania doing fieldwork and a year in New York finishing his dissertation. That earned him a Ph.D in anthropology in 1997 and was published as his book Kuria Cattle Raiders: Violence and Vigilantism on the Tanzania/Kenya Frontier in 2000.

In 1999, while working for the International Livestock Research Institute in Ethiopia, he met Chaltu Lina Ruda, an Ethiopian native. They married June 24, 2001 in Ethiopia.

By 2002, Fleisher embarked on a new career as a freelance anthropological consultant on research assignments for humanitarian organizations around the world. In 2007, this took him to Afghanistan and Angola. In all, he worked in at least eight African and two Asian countries. Many of these projects were quite risky. Among other things, he was involved in locating, mapping, and removing land mines in Ethiopia, Cambodia, and Afghanistan. He also investigated human trafficking in Kenya, Tanzania, Uganda, and Burundi.

Also in 2007, DC re-released his original three Encyclopedia volumes. That same year, Fleisher self-published both Shambler, a fictionalized version of life in the comics field in the 1980s (that he’d written in 1986), and a reprint of Chasing Hairy. The latter is also available at the Internet Archive.

Over his twenty-year career in comics, Fleisher wrote nearly 700 comic book stories for five publishers in two countries and compiled a comprehensive encyclopedia on superheroes (about half of which remains unpublished).

In his Comics Journal interview in 1980, Fleisher reflected on his feelings about his chosen profession. “I think writing is wonderful,” he said. “I think to be a writer is to live a blessed life.”

Michael Fleisher is survived by his mother, Nell Moskowitz, a half-sister, Vicky Moskowitz, two half-brothers, Steven Moskowitz and Martin Fleisher (winner of a 2017 World Bridge Team Championship and an attorney), his wife, Chaltu Ruda, a son, Thomas Fleisher, 14, and a daughter, Noelle Fleisher, 9.

Additional information

“Harlan Ellison: Notes on an Industry in Progress” (Interview from The Comics Journal #53) The Comics Journal Library 6: The Writers, Fantagraphics Books, 2006

“The Blessed Life of Michael Fleisher: An Interview With the Man Who Stuffed Jonah Hex” The Comics Journal #56, June 1980

“Trial Coverage,” an overview of the trial, including transcripts of testimony and closing arguments: The Comics Journal #115, April 1987

“Lawsuit Hell: The Trials of The Comics Journal”: We Told You So: Comics as Art, Chapter 4, Fantagraphics Books, 2016

Charles Platt attended the trial and wrote a report.

Colin Smith on “The Last Bounty Hunter”.