There are, as we increasingly know, a startling variety of artists who came through comics in one way or another. One of the most unusual was Herbert Crowley, who only published fourteen installments of "The Wigglemuch" in The New York Herald in 1910, some of which I reprinted in my 2006 book, Art Out of Time. Then Crowley mostly vanished from the published record. Some of the original art for these strips, along with other drawings, were exhibited in 1966 at The Metropolitan Museum of Art in a two-person show with Winsor McCay, an exhibition that I remember some of the NYC-based underground cartoonists mentioning as important.

There are, as we increasingly know, a startling variety of artists who came through comics in one way or another. One of the most unusual was Herbert Crowley, who only published fourteen installments of "The Wigglemuch" in The New York Herald in 1910, some of which I reprinted in my 2006 book, Art Out of Time. Then Crowley mostly vanished from the published record. Some of the original art for these strips, along with other drawings, were exhibited in 1966 at The Metropolitan Museum of Art in a two-person show with Winsor McCay, an exhibition that I remember some of the NYC-based underground cartoonists mentioning as important.

Looking back on my own interest in the strip, now I realize that "The Wiggglemuch" strips were partly compelling because Crowley suggested an affinity with a larger and also esoteric visual and literary culture, which was unusual in comics at the time. The spiritual allusions, stiffness, and symbol-driven character design also suggested another way to think about comics entirely: less drawing-based and more like moving sculptures. I wondered then, as many others did, just how he intersected with comics. As it turns out, Crowley really was just stopping over. His life and work is now the subject of a large and generously illustrated book, Herbert Crowley: The Temple of Silence by Justin Duerr. It is the kind of scholarly and research-driven deep dive that I wish for about... well, most everything. Duerr gathers every conceivable strand of Crowley's unusual and extremely complicated life and work and weaves them together into a coherent and quite moving whole.

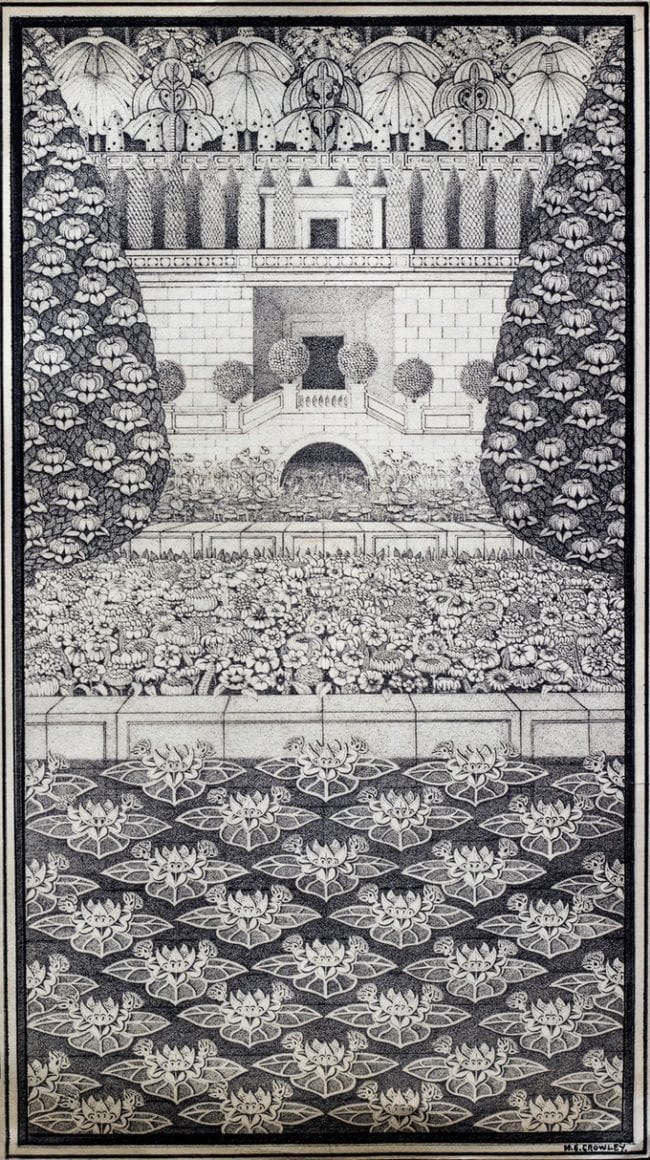

Duerr begins the book with a lengthy illustrated biography of Crowley, and then turns it over to absolutely stunning reproductions of Crowley's work, including the complete "Wigglemuch" run, plus two-unpublished installments, and numerous drawings and paintings. The artwork, aside from the comic strips, is wonderful, but not entirely unique to him. The imagery -- gargoyle-like forms, temples, and other mystical symbols -- is in keeping with slightly older contemporaneous Symbolists, like Odilon Redon and Felicien Rops, and the proto-Surrealist literature bring published at the time in Paris. It is certainly connected to last year's incredible exhibition at The Guggenheim in New York: Mystical Symbolism: The Salon de la Rose+Croix in Paris, 1892–1897.

It’s funny… this is the kind of project I always wish concludes in some astounding trove that enlarges my impression of the artwork. That didn't happen for me. The art just doesn't quite transcend its esoteric trappings. But then, someone more invested in early 20th century esoterica might entirely disagree. I'd love to read a Symbolist scholar's take on this. What emerges from The Temple of Silence is a minor artist of major passions and tremendous skill who made an arguably major and nearly forgotten contribution to comics and led a fascinating, incredibly active, and searching early 20th century life.

Crowley was born in England in 1873, and was a musician in Paris, Toronto, and New York in young adulthood. He first exhibited his artwork in 1903, and moved in bohemian circles in Manhattan at the time. In 1908, Crowley was in Rockland County, New York, in an early artist's colony that counted Peggy Guggenheim and Beatrice Wood, who would later work closely with Marcel Duchamp, among its visitors. This may have been the earliest artist settlement of Rockland County, which was also the (vast) site of other communes and colonies, including one known informally as "The Land," which housed John Cage, among others.

Anyhow (I'm leaving out a tremendous amount of detail, which I highly recommend you read the book to discover), Crowley seems to have found his way to the New York Herald via a friend, but the strip clearly didn't last. At that point, the characters come loose from the strip and occupy numerous drawings and sculptures. Through it all, Crowley emerges as a depressive romantic, somewhat impractical, and frequently reliant on the generosity of friends. Later in the decade, he entered into a relationship and eventual marriage with a wealthy woman named Alice Lewisohn, who helped fund the 1913 "Armory Show" in New York, in which Crowley exhibited, and co-founded the forward-thinking theater, The Neighborhood Playhouse, in 1915. Crowley was profiled in newspapers and magazines in 1914 and 1915 as an artist of "Grotesques and Mysteries." Lewisohn, meanwhile, became a principal benefactor of the groundbreaking bookstore the Sunrise Turn, which exhibited Crowley and Charles Burchfield, among others, and famously bootlegged James Joyce's Ulysses when it was banned in the States. Duerr details the store, Lewisohn's life, her connection to theater, and how it all related to Crowley. I used the word above, but again: This is a generous book. Nothing is held back -- I can't imagine anything missing -- and nearly every node in the web of events and places and people (the highly independent and visionary women in his life, for example, deserve their own turns) that is Crowley's life could and should be its own essay.

Duerr is very good on all the facts, and also on the evidence of Crowley's tormented state of mind, though sometimes I wish he speculated a bit more. The artist himself left behind far less testimony than those around him, and so he remains an appropriately mysterious center around which all of Duerr's research circles. Crowley was always dissatisfied, seemingly depressed, and forever searching for a spiritual balm of some kind. After fighting in World War I, Crowley, with Lewisohn, took what could only be called a seeker's journey through Egypt, Greece, Burma, and India. By the late 1920s the couple were living in Zurich and undergoing intensive analysis with Carl Jung, who apparently found the artist intimidatingly inscrutable. Crowley, for his part, was tortured by analysis and eventually left Jung in the early-mid 1930s. Crowley died in 1937, just two years after he married for the second time. Despite the artist's wish that his art and papers be destroyed upon his death, Alice Lewisohn donated her collection of his work to the Metropolitan Museum of Art, and his family also has holdings. Unfortunately, little is dated, so we can piece together a chronology mostly via letters and biographical evidence.

This is the kind of book that rarely gets made (unless it's just an book-length essay, and I would encourage Duerr to release an expanded version of the prose as an inexpensive paperback -- it's too good a story!), given the artist’s obscurity and, frankly, his isolation. One would normally need some larger points of contact -- a famous mentee or mentor, a larger output, etc. to connect to. With Crowley, it's all by proxy, even to Carl Jung, who was much more interested in his wife. Partly because of the sense that this is a life and a world entirely resurrected through Duerr's own obsession, it's impossible not to be completely enraptured with The Temple of Silence, no matter your opinion of the art itself. And part of the joy of looking at these pictures is understanding Crowley's story. I can see why Duerr fell so deeply into this project -- Crowley was a searcher, and though he never found satisfaction, it's his journey as the cliche goes, and as wonderfully charted in this book, that is the true destination.