In 2017, graphic novels are everywhere. The battle for “comics legitimacy” is over. Once seen as a vehicle for subliterary kids’ stories and crude comedy, comics now ranks as the artistic equal of the novel and film. Our current good times might make it hard to remember that, a mere twenty years ago, the world was an altogether different place: a comic-book wasteland. As a 1998 Washington Post review of Daniel Clowes’s Ghost World bluntly acknowledged, “This isn't the golden age of comics.” Yet the review promised that all was not lost: “there are signs of life out there for fans of the medium.” As one such sign it offered Clowes’s masterful graphic novel.

A sensitive portrait of outsider adolescence in 1990s America, Ghost World was serialized in Clowes’s award-wining comic book Eightball and released as a collection in December of 1997, twenty years ago this month. It holds a central place in the history of the North American graphic novel, appearing on countless critics’ and readers’ “best of” lists as well as in numerous college courses. For many readers, Ghost World is the comic that you give your friends to show them the medium’s possibilities. In the decades since its release, its reach has extended far beyond North America. Translated into twenty-three languages, it has sold over a quarter of a million copies worldwide. Along with Art Spiegelman’s Maus, Ghost World is one of the few 1990s comics to remain popular and influential in the overcrowded scene critics call our “new golden age of comics.”

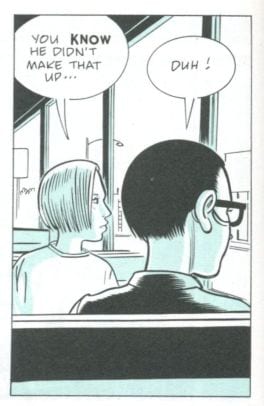

Like Maus, Ghost World was a revelation in part because its characters spoke like actual humans rather than the cardboard types that had long populated comic books. “For once in a comic,” the Post said of the graphic novel, “people are portrayed as they really talk and act.” Ghost World’s naturalistic, unfiltered dialogue was especially unusual for female characters, not only those in comics, but in film, television, and novels. Two decades later, readers are still drawn to the characters’ astute, acidic, and ever-relevant profanity-laced observations about the media, advertising, neo-Nazis, “pseudo-bohemian art-school losers,” and all forms of faddishness.

Reviewers have likened the comic’s dialogue to overheard conversation, imagining Clowes in a restaurant, pen and notebook in hand, furiously transcribing the banter of nearby teenagers, then transferring it to the comics page. While the dialogue reads like off-the-cuff speech, it’s also careful and complex: one seemingly simple phrase can suggest numerous meanings and connect to several important themes. The final line, in which protagonist Enid says of her former best friend Rebecca, “You’ve grown into a very beautiful young woman,” perfectly represents such textured writing. It’s a line worth exploring as we consider Ghost World’s achievement on the twentieth anniversary of this medium-defining graphic novel.

**

Enid’s line has a slightly stagey quality, as if she had heard it in an old movie — one other teens would never watch — and thinks it’s the kind of thing you say, the sentiment you want to feel, as you mark the finality of a closing scene. Enid acknowledges to herself (and to an imaginary audience) the tenderness of the moment she is creating. Though the line may seem stagey, even a little forced, Enid is certainly sincere, expressing genuine appreciation for her best friend. Her words are ostensibly addressed to Rebecca — Enid says “You’ve,” not “She’s” — yet Rebecca can’t possibly hear them, making this intentional failure to communicate directly the final act, or so it seems, of a troubled friendship with many moments of miscommunication and misunderstanding.

Enid’s appearance has changed as well. In the final scene, she wears the most refined and conventionally feminine outfit of the many seen in the book. Gone are the more unusual fashions, especially the punk “looks,” which had been a source of pride and anxiety for her. When Enid says “You’ve grown into a very beautiful young woman,” perhaps she is not addressing Rebecca, but rather herself; she wants to believe that she has naturally “grown into,” rather than consciously adopted, a new persona. This outfit is her most “adult,” the kind of clothes a young woman who wants to appear grown up might wear. Enid’s choice of outfit is significant; it shows her looking ahead to the future, to her place in the adult world. Throughout the novel she often looks backward, revealing her intense investment in childhood, as seen, for example, in her attachment to a toy given to her in the 5th grade, and to a children’s song she plays over and over:

When Enid says that Rebecca has “grown into a very beautiful young woman,” she rhetorically positions herself as an adult, as someone capable of recognizing and appreciating her friend’s growth. Yet is this how Enid really feels about Becky? This carefully crafted sentiment may mask something less pleasant, something that reflects the increasingly tense nature of their friendship. Three pages earlier, Enid watches a child being cared for and quietly says aloud, “You little fucker.” The child has what she wants: a caring mother. Does Rebecca, sitting with Josh in Angel’s, have what Enid wants? In the closing scene, Rebecca and Josh occupy the restaurant booth where Enid and Rebecca had spent so much time.

Though she’s sitting with Josh, she’s not looking at him — is she’s thinking about Enid? Since the girls had connected so strongly in the past, it’s easy to imagine that they are thinking about each other at this crucial moment.

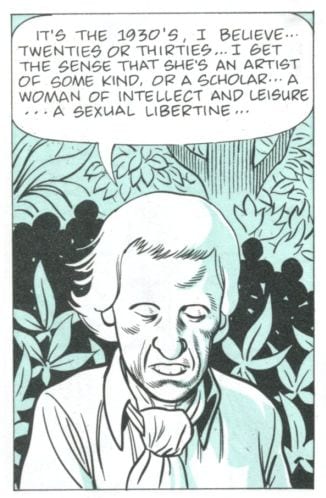

Enid decides to leave because many things in her life have gone wrong: she failed to get into college, she regrets changes in her friendships with Rebecca and Josh, and her father is dating an ex-wife she hates. Enid’s departure may be inspired by Bob Skeetes and “Norman” (the name she gives him), oddballs who haunt the margins of Ghost World yet exert an inexorable pull on Enid. Like Clowes, she finds outsiders compelling; Skeetes and “Norman” play crucial roles in her life even if their ‘screen time’ is limited.

In coming-of-age stories, the protagonist typically grows up in some way, gaining a new understanding of the world and her place in it. But the kind of growth that matters most in Ghost World might be growing apart. That Rebecca has “grown into a very beautiful young woman” means that Rebecca is growing up and away from Enid. Throughout the comic, Rebecca engages more easily with the world than Enid does; Rebecca is interested, for example, in politics, one subject among many that Enid disdains. By the end of Ghost World has Enid become more like Rebecca? Has she learned something new about the world or herself? Has Enid grown up? Clowes never answers these questions.

Changes in Enid and Rebecca are visually set up — and possibly even undermined — by literal signs of decay that we can follow throughout the story, a narrative that subtly, almost subliminally, parallels the deterioration of the girls’ friendship. In this narrative (a visual 'sub-plot'), the sign for Angel’s — a restaurant closely associated with Enid — repeatedly loses letters:

In the final scene, another sign carries symbolic significance: a sign for school children.

**

By virtue of their location, opening and closing lines of a film, novel, or comic have an obvious importance. It makes sense, then, to read the last line of Ghost World in concert with its first (which is also spoken by Enid to Rebecca). When Enid says the final line, she’s looking at Rebecca; but Rebecca, inside with Josh, doesn’t see or hear her. When she says the opening line, the girls are together in Rebecca’s bedroom (the clock and night setting indicate it’s 11:06 pm, a contrast with the last line’s daytime setting). Enid asks about a magazine she finds: “Why do you have this?”

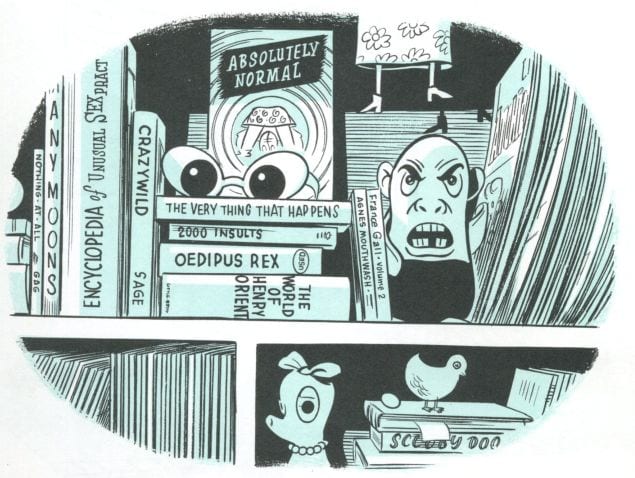

An obsession with mass culture, consumption, and authenticity will define much of Enid’s struggle throughout Ghost World. One of the comic’s first images shows her as a consumer and collector:

_____________________________________________________________

Ken Parille is editor of The Daniel Clowes Reader: A Critical Edition of Ghost World and Other Stories. He teaches at East Carolina University and his writing has appeared in The Best American Comics Criticism, The Believer, Nathaniel Hawthorne Review, Tulsa Studies in Women’s Literature, Children’s Literature, Comic Art, Boston Review, and elsewhere.