The following interview with cartoonist Gahan Wilson and Fantagraphics publisher and Comics Journal Editor-In-Chief Gary Groth originally appeared in the 2011 Fantagraphics collection of Wilson's Playboy cartoons.

Gary Groth: I’d like you to relate how you and Hugh Hefner hooked up. As I understand it, you wanted to submit work to Trump, the magazine Hefner financed that Harvey Kurtzman edited after he quit Mad.

Gahan Wilson: Yeah, Trump was this incredible, slick, beautifully produced magazine, which was a humor magazine, and they had drafted—stolen away—from Mad, Harvey Kurtzman, who created and edited it. I saw it and I just thought, “Well, I have got to be in this magazine, no two ways about it.” I visited my parents in Chicago every Christmas and spent about a week with them and then I’d go back to New York. So, I called Trump up and set up an appointment during that period. I turned up with a bunch of stuff—a little dossier—all set, ready to show them.

I turned up and there was the receptionist and I said, “Hello, I’m Gahan Wilson and I have an appointment.”

And she said, “Oh, yes, yes, yes….”

Did you think you had an appointment with Harvey Kurtzman?

Well, then I said, “With Harvey Kurtzman.”

And she said, “Oh no, no, no no.”

And I said, “But he’s the editor of Trump, isn’t he?”

And then she said, “Yes, yes. But the offices of Trump are in New York City.” And so I just sort of gaped at her and I was flabbergasted.

I had never felt that… and then this guy came up to me and said, “Hello, I’m Art Paul and Hef would like to see you.” And then he led me through this little door—the whole thing was in this very nice brownstone….

A brownstone is actually a house, a home?

Yeah, they come in varying sizes. It was an elegant old place that somebody had and I’m sure it had gone through numerous transformations. Hefner bought it and fixed it up.

So, I followed Art who pointed me up a narrow staircase and I went up into this little room with one light only on the desk, and the shades pulled, and there was Hefner. He was speaking on the phone and he smiled at me and shook my hand and waved me down to a chair and I sat and he said—and I quote, [mimicking his voice]—“Well,” he said, “it’s a very good story, very good story. Very well written and well composed, we like it very much. Very good writing, but the problem is that it’s anti-sin and we’re pro-sin.” [Groth laughs] I succeeded in not gaping at him and he went on saying nice things to this fellow, quite soothing, and then he hung up and stood up and he reached out a hand again, shook it real firmly and said, “I’ve been waiting for you.” And that’s how we got started.

You were nonplussed because you hadn’t heard anything like that from an editor.

Well, yeah. I’d usually get to see some sub-editor or something like that. This was just incredible. It was very foolish of me not to have gone to Playboy before or sent stuff off to Playboy before because he and A.C. Spectorsky—who was quite a figure among the intelligentsia; a brilliant man and a sweetheart once you got to know him—had this policy. They printed wonderful authors there, had really good fantasy and science-fiction stuff as a regular item, and were the first magazine ever to pay decent amounts of money for their genre. So, they really rose to the occasion. So, I should have thought, “Well, for pete’s sake, they print that kind of stuff, they should go for my cartoons.”

Well, I didn’t because the cartoons mostly were these clever little sexy cartoons and I just didn’t realize—didn’t make the connection. It was just dumb of me.

I became a regular with Playboy and eventually Hef moved to another building and that’s where he had the apartment on the top floor. This is maybe five years later. He was—and is—a terrific editor, he’s just marvelous, brilliant, it’s awesome how good he is. He writes in the bottom of the thing a little something in red pencil, signed “HMH, full color, full page.” Sometimes he’ll add a comment and if he does, it’s always very apt or very useful.

A few years later he moved to a larger building with his lodgings at the top and around noon—he was always, as far as I’ve known him, a night person—he’d descend the staircase from this apartment and I remember watching this from this little desk I was at, doing some special spread at various occasions. The editors’ offices lined the walls and he’d come down in a sort of trance, staring vaguely in front of him. As he came to the door of this editor’s office, if the editor had something to show Hef, he’d be waiting by the door and he’d jump out and he’d present it to him. Hefner would look at it instantly with intent, amazing, eagle-eyed focus and make quick decisions, talking very quietly. Then he’d go into a trance again and move on until the next editor grabbed him and do the same thing—instantly focused. I thought, “He’s a fucking general!” It was amazing.

It’s downright scary to see him at work, because he just focuses with astounding intensity on whatever it is that he’s looking at, and he’s just looking at that, everything else doesn’t exist. He takes a detailed interest in everything. So it’s very, very, very intense. That’s why it’s usually right, he’s really thinking it over.

I guess that’s why he was able to do what he did.

Yeah, and then when you see him switch from one thing to another, and go blank in between, you know you’re looking at something kindred to Napoleon [laughter] or all these other characters who were handling incredibly complicated operations of one sort or another, but kept everything in order, but noticed everything. The brilliance of that kind of executive is that they have a sea of minutia, and it all has to work out, and everything really has to be noticed, although it can’t be—you’d have to be God in order to really take it all in. But they come close to it, and he’s one of them. I’ve thought now and then it would be fascinating to be in the war tent of some high-level thing, where you’ve got this bunch of super-duper pros, and there’s all these guys out there, all these little maps and charts representing human beings, and they’re trying to make it all work. ’Cause every one of those—you know, those are people, really.

That’s an amazing facility.

It really is. It’s a special knack. And sometimes at a magazine, you’ll see it in a really good director at work. It’s extraordinary, they’re just taking everything in, and they notice every goddamn, teeny-itsy-witsy stuff: all these people who are specialized and incredibly brilliant and talented and accurate and expert in every way, but they miss this thing in their little special zone—but the director spots it.

As a cartoonist, though, you must have something of that focus when you sit down and hunch over the drawing board to do one of these cartoons.

Yeah. This documentary they did recently was a shock to me because I’d been photographed many times—God knows how many—posing by a drawing board, supposedly working on something, and it was convincing. It looks like I’m working on something. But when I was filmed extensively for the documentary that director Steven-Charles Jaffe recently did of me called Gahan Wilson: Born Dead, Still Weird, he had the camera on me while I actually was working on something, and the intensity and focus was very akin to Hefner’s. I saw myself for the first time, working, I was doing the same thing. I sometimes do some work and I’ll just be exhausted and I’ll think, “What the hell am I so tired about?” I understood after looking at that. I was just like a hawk—just on it, you know?—glaring at whatever the hell it is. So, that’s a great insight into him.

You probably were 27 when you met Hefner. He must have been a little bitolder than you—or was he?

Oh yeah.

Your first drawing appeared in December 1957. And then you’ve been in

virtually every issue since then.

Yeah, he’s made a sort-of point of that.

Hefner was aware of your work from Collier’s?

Yeah, apparently. I was mostly in that magazine and in Look.

And so before you did your first drawing for Playboy and before you started being a regular in Playboy, what was the editorial discussion like? What did he tell you that he wanted and what were the parameters?

No, no, nothing like that. I designed the works I submitted vertically—hoping for a full page—and just made them as good as I could. And that’s all.

So once he accepted you into the fold, you were given as much freedom as you really wanted.

Oh, yes. I’d send in a bunch of the things, and hopefully he’d buy some.

Did you take into account, when you were drawing the cartoons, that you were drawing for Playboy? Did you draw differently for Playboy than you did for other magazines?

Well, what he gave me was this wonderful thing of being able to do full-color, with good reproduction, so I would work with the idea that I could pull off all kinds of subtle visual effects. Actually, that connects very much with being a director. A cartoon is just like a shot, and you light it and so on. Like, for example, if I’ll have some sort of light source I’ll make a little “x” where that light is outside the margins of the drawing, so the rays will come right. It’s like lighting it. And then I costume the characters, and I do the sets, and the character faces, the whole thing. It’s just like putting together a shot for a movie.

Tell me what the process was like. You would send a certain number of

cartoons every month?

Not necessarily every month, sort of irregularly. Twice a month, sometimes. But it was always a steady income of stuff going in to him.

But you would send a batch? You wouldn’t just send one.

Oh, yeah. Always send a batch.

How many would that be?

It would vary. It would go from a dozen, to 20, tops. Rarely more than that.

You were still living in Greenwich Village when you started contributing to Playboy.

Yeah.

What were your work habits like?

I had a marvelous fun stretch, because now I had this regular, reasonably reliable income, and I went over to England and I lived there for a stretch. And then I traveled over Europe. And of course the dollar was, at that point, extraordinary. It was wonderful.

How long did you do that?

That was about a year and a half. And it was just terrific.

And you were able to do that because of your Playboy income? You were able to draw your Playboy cartoons over there and send them over?

Yeah. It was just fabulous. And also American Express would have this setup—in those days, they no longer do it—where you could go to one of their offices and make that your mailing address and then, if you were in Country X, Town 1, you would say “Okay, I’m going to Country Y, Town 3, would you forward the mail there, please,” and they’d do it.

And that actually worked?

Yeah! I imagine it’d just be too much. But the combination of those things was fantastic. One of the smartest things I ever did. That way I just wandered around.

That sounds fantastic.

It was. It was just marvelous.

Why did you ever come back?

I sometimes wonder [Laughter].

When you sent cartoons in, did you send finished cartoons or roughs?

Oh, roughs.

Then he would choose which ones he wanted, and you would finish them.

Right. That’s the process almost universally.

At the beginning, when you started working for him in 1957, 1958, I assume he did not have a cartoon editor.

No.

And that he edited the cartoons personally.

Yes. See, he wanted to be a cartoonist. He worked very hard at it, but it just didn’t work. So he compensated by becoming Hugh M. Hefner. Poor devil. You don’t feel very sorry for him.

Yeah, if you can’t be a cartoonist, you might as well be Hugh M. Hefner.

Might as well be Hugh M. Hefner. Right. But he still is—he’s it, as far as cartoons are concerned.

How did it come about that you did what I would call the “thematic galleries,” where you would do three, four, five pages at a time on subjects like Sherlock Holmes, or Edgar Allan Poe, or so forth?

They call them “spreads” in the business, and I would just take a theme.

Would you propose that, or would they propose that?

I’d do it. And some of them were based on a European thing. One of the first I did, I think, was Madame Tussaud’s Wax Museum. So I just went around, sketched stuff, and made cartoons out of it.

How would you describe your relationship with Hefner evolving over the years? How well did you get to know him, and how close did you become?

Oh, I love the guy! He’s just very open and a very sweet guy. When he was in Chicago, I stayed at the Mansion, which was a whole different thing from the Mansion West. It was a great big robber-baron thing, god knows who it was that built it, it was like a fort. He’s very accessible, and he’s swell. He’s a very perceptive, bright and extremely sharp.

What would you guys talk about?

Oh, god knows what. Just practically anything. He’s a remarkable guy. Historically, I think, he has yet to be appreciated, although I’m beginning to run into various intellectuals who are planning essays and studies and so-on on him, because he essentially—and it was on purpose—changed the country. He changed the attitude.

And you were sympathetic to those changes?

Totally! We had this kind of puritan thing, which is very understandable—you can see why we did. It’s in our history. But he changed the idea of sexual stuff from dirty, smutty, yucky, cruddy, to very nice, very fresh air, very sunny, very bright, very healthy. And I think someday he’s gonna be recognized. He’s like—well, I mentioned P.T. Barnum—

I think he’s as influential as P.T., as a transformer of society. And he did it very cleverly, on purpose. He schemed things out, like with the frontal nudity, which was a no-no. What he did is extremely clever; he did a spread of greatest, most famous artists in the period—I guess it was somewhere in the 1960s, or late 1950s—he got all these guys who were legendary famous artists, and the assignment was, “Do me a Playmate, as you visualize her.” And, of course, in every one of them, automatically, there’s frontal nudity. They didn’t think about it. So there you were. And it was art, so the censors couldn’t do a damn thing about it. So he got that in; it was the first general publication that—there it was, on the newsstand, frontal nudity, and because of that dodge, there was that precedent. He followed that with a very artsy photo spread of a black female athlete—I can’t think of her name—done by some legendary photographer, whose name I also cannot think of. This too had, automatically, some frontal nudity, so he’d moved it into photographs. Again, they couldn’t do anything about it, so he’d established the second precedent. And there the horses were off. Everything he does, he plans very carefully. He’s a great gentleman, incredible. God help you if he started a war.

[Laughs] You were a Midwestern kid, and your dad was a Republican. Where did your openness to Playboy and your generally progressive nature come from?

For one thing, I was knockin’ around with bohemians.

But you must’ve had a propensity to do that.

Yeah, sure, I was a bohemian myself.

So were you reacting against—?

No, it just was more fun that way. And made more sense. And I got left very early on—when Henry Wallace was running for president, I went around on the Near North Side, passing out pamphlets, and was going through that sort of thing. I liked the attitude. But I had a very disillusioning thing because the Communists would have parties, and they’d be very nice parties. They’d have free food and drinks. But I noticed that they’d have these very artificial little discussions which would “just naturally happen,” and some wise Communist would sit there, and everybody would cluster, and this wise Communist would come out with this bullshit, and everybody would nod. And I thought, “Well, this is horrible. I do not like these people.” And there was this friend of mine who had been in Todd School, which would occasionally take in somebody to help. And this guy was Jose Rodriguez—he was from Guayaquil, Ecuador, and I don’t know how it all came together, but they took him in in grade school and brought him all the way through high school. They used him, the Communists. So I became quite anti-communist, in that sense. But I’m definitely on the left side.

It’s interesting, this nexus, where all these cultural leanings converge. Because you wouldn’t think of––well, would you think of Playboy and bohemianism?

No, not really. [pause] Well, it’s a pleasure thing.

Which can somehow encompass bohemianism.

Yeah. It’s a very pro-life kind of thing.

Tolerant. A good home for you.

Yeah, it’s open to discussion. You can talk about this, you can talk about that.

It must be very different from The New Yorker.

Yeah, it’s a whole other—oh, yeah. Completely. And also, it’s a one-man operation. It’s very much Hefner.

Over the years, my impression was that Hefner gave up some editorial control of the magazine to other editors, or to people he’s hired, or whomever.

Through the years, every so often, there’s been some people who have moved in and tried to change it. And usually it ends with him just firing the lot of ’em. [Groth laughs.] Several different times, this has happened. So he’s not to be crossed.

But he’s maintained his interest in cartooning throughout the years.

Oh, yeah. He’s a frustrated cartoonist, which he admits. He says that it just dawned on him—he just didn’t have it. But he was a good editor, he realized that. The guy’s very intelligent, and he’s a realist, too.

One of the facets of your work is that each cartoon is based upon an idea, but it’s the drawing and the idea combined that make it work, and the drawing has to be funny. In other words, the same idea with a different drawing would not necessarily be as effective. Could you talk a little about how you developed your particular approach to drawing so that it’s intrinsically funny?

It’s like, in reference to the movie director business, you have a script, and what you do is you cast carefully so that the actor is appropriate for the character that’s written, and the theme, you wanna have it look authentic. You have to take into account the atmosphere of it, and the lighting. And then you go into costumes and the whole business. You have to go through all that stuff. And the director has the luxury of costumers and so on and so on, but you’re really doing all the separate duties, but you eye it the same exact way as a director would.

One of your stylistic quirks is that you draw these everymen (and everywomen) with these rubbery, scrunchy, fleshy faces. I can’t imagine your work without that particular quality. You once mentioned how you were impressed by the looks on people’s faces when you were a kid during the Depression. And I wonder if it all comes from that.

I think certainly I must’ve been aware, or I wouldn’t have had that flashback.

The expressions on the people’s faces are expressions of panic or fear or horror, or even resignation or bewilderment—

Yeah, that’s well-observed. And again, as in a film, if you’ve got an eerie, fantastic event, it’s strengthened if the people, flesh-and-blood people, react to it appropriately, and look very flesh-and-bloody in the presence of this astounding whatever-it-is. It fills it.

Politics doesn’t rear its head in your cartoons often. But when it does, it’s incredibly potent. You seem especially interested in conservationism—or what used to be called conservationism.

Very much so. I was into the destruction of the planet Earth quite a while back, way before it caught on as a cause célèbre. One part of it I think was the Acme Steel Mill with its death-making machinery, situated in the little towns around these places that were poisoned, very obviously. And you could see the acid’s effect on the walls, the boards of the houses, and on the rooftops, and on the vegetation and so on. And I think that alerted me to the casualness with the fragility of the thing, and the callousness. And also, really, it’s a terrific joke that we have this one really teeny fragile place and we seem to be intent on destroying it, and I suspect, irredeemably started a process of doing it. But yeah,

I became aware of that quite early on.

One of the earliest cartoons on that subject was published in 1970, where you have two people in a Washington D.C. Senatorial office—the Washington monument is in the background—and they both have these enormous gas masks on, and the one guy is walking and saying “I’m sorry, Senator, it’s some more of those crackpot conservationists.” And it occurred to me that a lot of your cartoons—

Yeah. Oh, I’m absolutely furious at it, and I had this fantasy that it might alert some senator, you know.

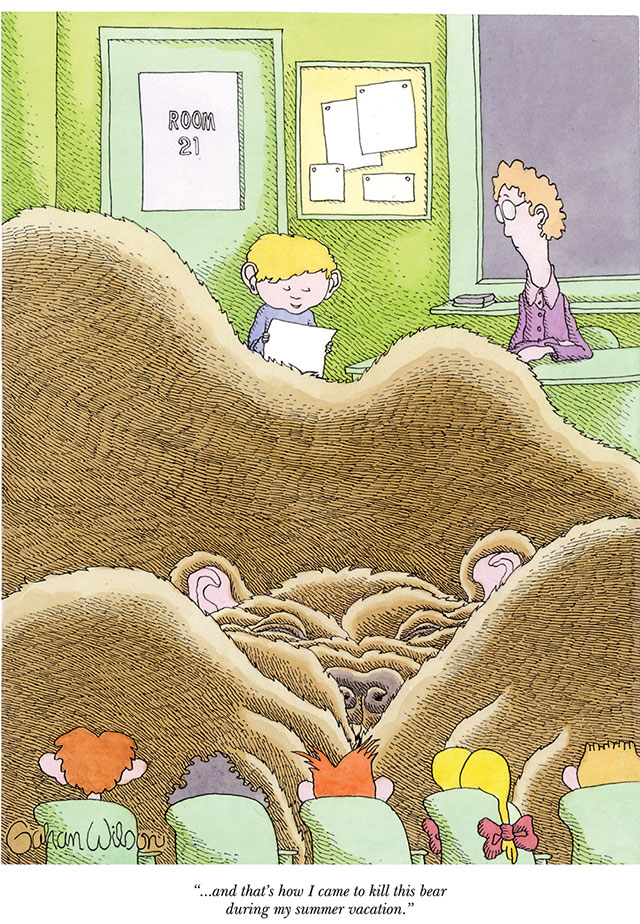

And then, I don’t know if you heard this story or not, but I did a cartoon once which had this living room—some suburban place—and the couple that own it cowering behind chairs, and outside you see all kinds of animals prowling around, and there’s a bear trying to get in the kitchen window. And the guy says, “I knew this would happen if those crackpot conservationists had their way.” And this incredibly odd thing happened where my father wrote me a letter—he almost never wrote me a letter—that he was so touched that I had finally come to see the truth. He completely misinterpreted the cartoon and thought I was against the crackpot conservationists. And at that point I realized that this is not working. [Laughs]

He was firmly anti-planet Earth, although it would never have occurred to him, and he would’ve been shocked and saddened had he thought that I thought that. And he loved nature! He loved to be out on his boat in the water and so on. But they just—I don’t know…I just don’t get it.

Well, it may be generational. There was such a lack of awareness, I think, at that time.

And the present crew…now it’s been turned into a kind of a fad, and I suspect a lot of the stuff that they’re doing is about as useful as those little green mouth patches they’re wearing in Mexico.

Some of these cartoons, not only the ecological-oriented cartoons, but you also have cartoons that refer to nuclear armageddon and “The End of Civilization” and so forth—

The Eskimo’s probably the best one in that category.

Where the Eskimos are looking up at the missiles?

That’s probably the basic statement.

Now, was Hefner as welcoming to those kinds of cartoons—?

Actually, he said he liked that one the best of them all.

I ask because in a way I thought they were a little…not anti-Playboyish, but Playboy stood for hedonism, for consumerism, and…

Well, Playboy, you get right down to it and…it’s intriguing, the difference between Hefner’s approach to sex and pretty girls and so on…nobody’s given him credit for this. All the magazines before, and there were lots and lots of them which had naked or half-naked ladies, were all smutty. The ladies were assumed to be whores. It was disgusting and shameful, but “isn’t it fun.” It was not a pretty display. It was nasty. Sex had the implication—it was an affirmation that the righteous minister is correct about the body and its evils and so on. But Hefner, the pretty girls he has are carefully chosen—the sort of girls that you really could take home to mama.

The girl next door, right.

Yeah. And they’re proud. They’re not sluts. They’re healthy. You wouldn’t get VD from them. It’s a very positive approach to sex, to life, basically. So he’s pro-life. He’s one of the good guys, I definitely think.

Let me ask you this about that. Playboy presents this prettified view of the world. Pretty girls, pretty cars, and…

Yeah, it’s a have-a-nice-time sort of thing.

But your work clashes with that, in the sense that it’s deeply—I don’t know if you’d call it misanthropic, but it can be pretty harsh in its point of view. And yet Hefner’s tastes are broad enough to encompass both of those.

Well, as I say, he continually ran short stories and interviewed authors who were exploring that kind of stuff too.

True. But did you ever get any sense that what you were drawing was somewhat, or occasionally, antithetical to the Playboy point of view?

Not really, no.

You published several short stories in the magazine, which we are publishing here. When did you start writing prose?

Oh, geez, that’s quite early on. I really don’t know when I did.

Your first story in Playboy appeared early, in 1962.

Is that when, huh?

“Horror Trio.” What prompted you to write prose stories?

Oh, I love that genre, of course.

Were you a big reader?

Oh, yeah. And so I just eventually got into writing it, too.

So you basically wrote a story and submitted it to Hefner?

Yeah.

And it was as easy as that?

It turned out to be, yeah.

You obviously like writers like Poe and Lovecraft.

Oh, certainly, yes, of course.

“Horror Trio” is a traditional horror story; “The Manuscript of Dr. Arness” is about the pitfalls of immortality or, more generally, of the the dangers of getting what you want. Your next story, though, was “The Sea Was as Wet as Wet Could Be,” and I thought that story was quite a bit different from the previous two, because it was almost reminiscent of F. Scott Fitzgerald.

You’re right, I hadn’t thought about that before you asked me, but right, it’s very F. Scott Fitzgeraldy. It really reads like one of his pieces.

Yes, in its observations of the adult couples in the first half of the story. The tone is really masterful in a way that I thought the previous two weren’t, quite.

Yeah, he’s got all these—he wrote god only knows how many things—about just walking through a room and getting exhausted. Yeah, F. Scott Fitzgerald for sure. And a great gentleness about it, and my character in the story loves that girl. And even there’s a sadness about the monsters. You and I have talked about James Whale. He got that all the time, the monster says, “Why?” And it’s very important that the monsters are treated affectionately, really.

Do you believe there’s a gentle dimension to your work?

Absolutely. Every so often I get mad as hell, but yeah, basically, you feel great pity and sorrow.

Or empathy, I think. You know the most clichéd question in the world is where your ideas come from—

Oh, all over the joint.

But I was wondering if you could tell me a little about the creative process. A lot of your panels are purely visual, and I think of them as quintessential cartooning: Cartooning that is expressing something that couldn’t be expressed in any other form. For example, the very second cartoon you did for Playboy has the woman sweeping, and she’s actually sweeping her shadow away. Could you walk me through and tell me how you come up with ideas? Do you just sit and stare at a blank sheet of paper until something pops up into your head? Do you take notes as you’re wandering through the day—

The core technique is, yes, you do have a blank sheet of paper and a pencil, and generally speaking, unless you’ve got some specific scene that you’re pursuing, you just latch onto something. Anything whatsoever, so…cleaning: that would evolve from that. When I taught cartooning, I told my students the important thing is to stay with whatever you’re wrestling with, and you eventually come up with something.

Do these ideas come to you in a flash?

Some come quickly, some sort of float up. My basic image is that your consciousness is like a fisherman in a boat on this vast sea, and what you do is you’re expert with this rod and reel and bait and hook technique stuff. And you toss your line over the water, and the thing sinks down, and you are sensitive to the tug of this little touch, and you pull it up and hook it, and then you reel it in. And it takes a lot of trouble to do that, and then you flip it into the boat, which is the final piece of skill, and you got it. But it’s all mysterious. The profundity of what we got inside there is staggering.

Once you nail the idea, does the drawing come easily?

Again, it’s just like building a set and lighting it and so on. It has to be appropriate to whatever the joke is, and you make it so that it’s focused on that. You see the same thing in El Greco, how he sets the whole thing up and lights it, and you see the eyes and the hands and the whole posture doing whatever this saint is up to, and even the furniture helps out and has to be right. It’s a whole gestalt.

When you have the gag fully conceptualized, do you usually do only one drawing or do you sketch variations?

No, it varies. Sometimes it’s just—zip zip zip zip—comes right out, easy as pie. Other times you really have to wrassle with it. I mean, sometimes you got a thing where you just gotta get the posture right on this fellow, and you have to erase and redraw, and erase and redraw forever, and you finally get it. And you see it when you get it. And then other times, it just flows right out of the pencil.

Speaking of ideas, I was astonished: Going through the book, I realized that you created a New Year’s joke virtually every year. I don’t even know how you could do that. [Laughs.] Do you put yourself in the New Year’s mode ?

You just have to do it. And then there’s Thanksgiving, and I found this time, initially, I had a terrible time coming up with Thanksgiving ones, ’cause it’s not as rich as the other stuff, so I had to really stretch out and dream up stuff that I hadn’t dreamed up before. I essentially have succeeded in doing it, I hope to everybody’s satisfaction, and so there’s about three of them there.

When you’re called upon to come up with a cartoon about a specific subject, like Christmas or New Year’s, have you ever panicked because you just couldn’t come up with anything?

No. When I teach cartooning, part of the thing I give ’em is how you go about making up ideas. One of the things I stress is that what you do—sometimes a cartoonist will be called upon to raise money for starving orphans or whatnot, and a little group of us will be on the stage with easels, and the audience will start calling out a place, a name, a character, a situation, and so on, and then you make a cartoon using these items right in front of the people. It’s quite something to see. But the thing is, what you do, if you’re gonna make up an idea, you’re sitting there and you say [makes thinking noises] “Chair, somebody on a chair.” And then you start fooling around with something on a chair. And eventually you’ll struggle through it and you think about something on a chair.

But if you’re in this situation, where people will start throwing out suggestions to the cartoonist—what they don’t do, and what the cartoonist does, is float around. There’ll be one thing, and then they’ll drop that entirely, and then they’ll start thinking about puppy dogs, and then drop that and do something about going to a delicatessen. But the only way you’re going to crank out a bunch of cartoon ideas is to give yourself a specific challenge. You start out with a specific topic, quite narrow, and then you just stay with it, like Thanksgiving. So that’s why I’m saying that Thanksgiving’s not unusual, it’s what you do all the time. Take one topic and wrestle with it until you come up with something that is funny about this. Otherwise you just spend a whole day dreamily going from Thanksgiving to Christmas to Hannukah to God only knows what. You’d be doing the Druid holidays and so on. And you wouldn’t get anywhere at all. You’d just sort of waft off to something else again, which is really pleasant if you want to relax sometime.

That sounds like it could be pretty easy to fall into.

That’s the core thing you have to get through their heads, or they’ll never be able to make cartoons.

One of my pet theories is that there’s an organic wholeness in the work of the best cartoonists, where everything comes together, from the line itself to the sensibility to the subject matter, and I’d extend that, in your case, to even the names you give your characters, which are both quintessentially ordinary and weirdly Wilsonian at the same time.

Well, it’s like if you’re writing a story, a very important part of writing a story is the characters’ names, both first name and last name, and the combination of first name and last name—they have to be appropriate not to just the guy’s or the woman’s personality, but to the whole thing: the whole gestalt. And then depending on the sort of story it is, there’ll be some kind of uniformity in the names. If it takes place in a London club, they’re all going to have London clubby names. If it takes place on the sidewalks of New York, who knows: all over the place. You’d select names on purpose to establish this rich hodge podge of all different kinds of people.

What medium do you use for color?

I do a pencil drawing on a piece of tracing paper, usually, and I work all the lines out. Then I tape that on the back of the piece of paper I’m gonna do it on, put that all on a lightboard. The reason I do that is because I used to do the drawing on the paper itself, but if it gets complicated, like with doing a hand right, or something like that, you can mess up the surface of the paper—even if you erase carefully. Also, if you do the drawing and you get halfway through and you screw up, all you have to do is just detach the pencil drawing from the back and put it on another piece of paper. So that reduces the tension. You don’t ruin everything if you screw it up, and have to redraw the whole thing. And then having done the inking of the line drawing, I take watercolors—good watercolors—and just fill it in appropriately. And when that’s all done I spray it with a fixative, so that holds it all down and I can keep doing layers, depending on what’s on it and what sort of atmosphere I want. I can do layer after layer of crisscross, or with pen, or rubbing with pencil, or add additional overpainting of colors, or even rubbing pastel, or all sorts of things like that. I can take as many as six different kinds of media.

What does the use of watercolor give you that other color media don’t?

I don’t want an opaque thing, because that would block out the lines. So watercolor’s the best. I usually find myself using the British ones; they seem to be best.

Much of your humor derives from creating a perspective so lopsided that it achieves a level of absurdity. For example, you did a fantastic cartoon of Hitler in 1970, where Hitler is fuming over some inconsequentiality.

Oh yeah, in the South American hideout.

Right, and some guy is saying, basically, “Get over it.” I think that’s the kind of thing that makes people stroke their chin and wonder, “How in the hell did he come up with something like that?”

Well, thank you. It’s like the fisherman. Often, it’s just totally mysterious. You’ll start trying to think, and pop! This thing will just be there. And I don’t have the vaguest idea of where it comes from, but it’s really a staggering demonstration of how much of your mental operations are unconscious.

It seems like such a cartoon must come from a different place than the cartoon, for example, where one hunter tells another hunter, “Congratulations, Baer, I think you’ve wiped out the species.” So, there are different parts of your creative intelligence at work in these cartoons. Would a cartoon like that come from outrage?

Yeah, that’s one of my ecological things. I must confess that I—well, I have total sympathy with people hunting, if they have to eat, or something—but I don’t get the idea of going out and killing some poor little squirt on a branch.

With an automatic rifle, probably.

Yeah, yeah. And then pretending you’ve had some sort of equal contest with a critter. It’s pathetic. And mean. The most romantic and glamorous and fantastic relative I had—a real tough bastard—was Uncle Mac, Mac McGavern. And he was by the Wilsons, who were an extraordinarily religious outfit. And I am related to William Jennings Bryan, which I’m very proud of, ha-ha.

He’s a great-uncle, right?

Yeah, he’s a great-uncle, and the other great-uncle that I really am proud of is P.T. Barnum. God bless him. But Bryan would come by and he’d have one of these huge breakfasts, and give a little speech as he ate it. And my grandmother and grandfather Wilson had a lot of kids, but they also adopted kids. In two cases, the kids ended up marrying one of the kids that they grew up with: sort of brother-sister, in a funny way.

Uncle Mac married Aunt Marnie (she was the Wilson). Mac was tough as nails. He had been a Marine in World War I, and then he came out of that and he joined up with the Pinkerton Detective Agency, and did detective agency stuff, and also beat up on unions that were getting too uppity—and so on. [Speaks gruffly] And he talked like this, Gahan. Tough, tough, tough. And he married Marnie and they went and established a successful saloon and restaurant in Bridgman, Michigan. He would take these outings, and he would go to the Southwest and hunt mountain lions—not to kill them, but to capture them. He would sell these mountain lions to lion tamers, so he got to know the best lion tamers in the business, and they taught him the basics of lion training. By this time he had established some motel cabins along with the restaurant and the saloon, and he set up a cage where he kept a couple of lions, and he would do a mountain lion taming thing which you could come see. And he expanded this thing into a zoo, which became a huge draw. It was quite a successful operation.

He was a very sweet man, for all of his toughness, and it was fascinating to see him with these creatures. I just loved him. I had this great picture—I don’t know where it’s gone to—there I am, this little thing about six or seven, if that, and I’m surrounded by baby lion cubs. Not the safest thing in the world. But I’m happy as a clam! Couldn’t be happier. So that may have something to do with the ecology thing. That was very extraordinary.

Let me get back to your drawing. When you know you’re doing a drawing in black and white, rather than color, do you ink it differently, knowing it’s going to be black and white?

Yeah. It won’t necessarily be a different line, but it’ll affect the whole thing, because you’re aiming at this color finish. So everything has to be consistent. Most of the colored stuff would actually be cluttered if it wasn’t in color.

So, in effect, when you’re doing a black-and-white illustration, do you use the pen and the ink as surrogate color?

It’s like shooting a black-and-white movie. You can get effects that way that you can get with color, if they will let you do bizarre effects. But the old sensational black-and-white crime movies were marvelous in black and white, because they were in black and white. And you could get away with all kinds of really neat, dark, startling stuff. An alley—you can’t do an alley better. It’s much better in black and white than it is in color. And also the open doorway—how many times do they have the door open, spreading this diagonal beam of light? How much better that looks in black and white.

You must be a fan of film noir.

Love it. Yeah, it’s great stuff. And it’s of its era, its time—and the black and white. There were some successful extensions of it into color, but really it worked better in black and white. There’s a nice tackiness you could get about it too, which you can’t do with color. Also with color you have tonal stuff, including lots of flesh tones, whereas the black and white can be a lot more brutal and a lot more shocking.

I think I’m a purist. I don’t think you can have film noir in color.

It’s appropriately named, yeah. And then you get into horror movies. Probably the best is James Whale. But the only people who took on color and then had fun with it in a horror movie were the Hammer people, and what they did was to go way back to penny dreadfuls and use that period—so the color was very stage-set-y on purpose—and had this delightful Victorian, or a little before Victorian, mood about it. That was jim dandy. They just made the whole thing fantastic.

Did you like Val Lewton?

Lewton was brilliant. His understatement was just staggering. The black and white was perfect. He could have this very subtle image stuff going on, which would be too realistic in color.

I don’t know you that well, but having read the entire book and all the cartoons, I have to ask you this: You seem like a very generous-spirited and sweet guy in a way. But do you think you have a misanthropic or cynical streak?

I must say that I have been profoundly shocked with the goings-on of the last couple of months, where I thought I was an extreme cynic, and it turns out that I’m like Alan Greenspan: a naïf, a total and absolute naïf. [Groth laughs.] Remember the sad confession he made?

Yes, where Greenspan admitted that his whole worldview, the consequences of which he’s saddled us with, was essentially wrongheaded.

Yeah, he said he really did believe these business people—the bottom line that was important was to satisfy the customer, and it never occurred to him they were just making money, period.

Isn’t that utterly pathetic?

Yeah, it was touching. I was very touched by it [Laughter]. But I had no idea these guys were as bad as they are, and I think that’s the thing that’s really very discouraging. It’s the same thing as with the Nazis. It’s astonishing how terrible people can be.

A combination of self-interest and cluelessness.

Yeah, and boogishness and a kind of cruelty that is staggering. And I had no idea, though I was going around being very suspicious of business people, because I’ve had some experience with them, with my father working with them, and having met a number of them—I knew that essentially they were in it for the money [laughs], and not to serve the public, as Greenspan seemed to think. “Satisfy the clan,” I think was his phrase. But I had no idea they are as horrendously crappy as they are, and that they would use such cruel and egregious, really just miserable, rotten, flat-out illegal con-game maneuvers to victimize the people they culled out as victims. The mercilessness of them: no sense at all of hurting people. They seem to be completely impervious to other people’s pain. I’m just flabbergasted. I didn’t know they were anything like this bad.

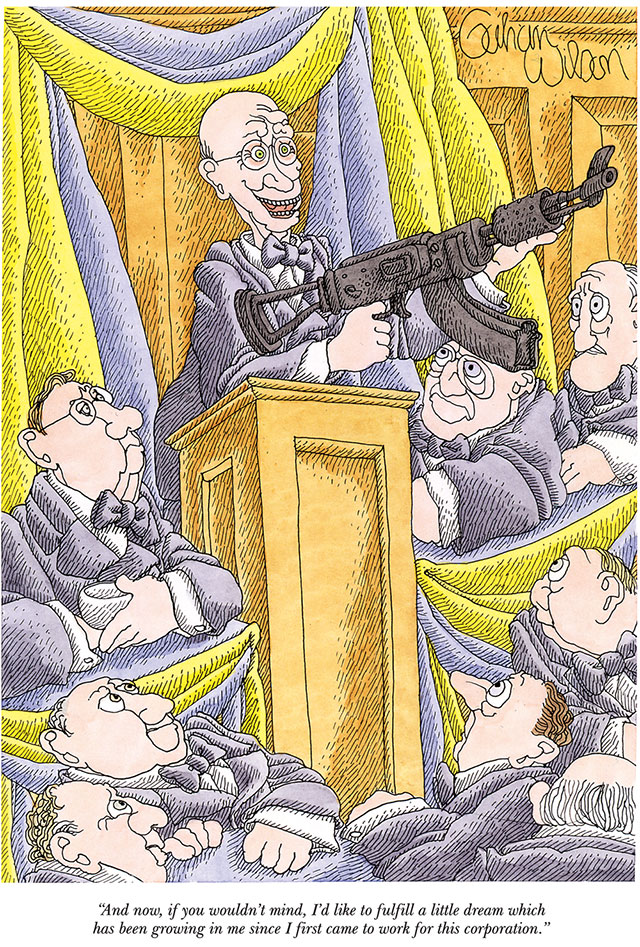

Well, you’ve been quite consistent in your criticism of corporate culture throughout your cartooning career.

With good reason. [Laughs.]

But you think perhaps not to a sufficient—

As I say, it turns out I’ve been a kind of Greenspan. I had no idea they were this bad. All my fantasizing was so short of the mark that I’m positively embarrassed. The thing I don’t understand, although you do a little bit if you mingle with some of these people, is that it’s such evil that they’re doing, you wonder, “How can they do it?” It’s very mysterious to me. And then they go home and be reasonably kind to their wives and children.

Maybe it’s naïveté that compels you to be so appalled by it. Otherwise you would just accept it as status quo.

Yeah. I dislike people mistreating people, and the casualness with which they do it. One of the cutest cons ever played was: “You can’t cheat an honest man,” which of course is total bullshit, and was invented as an excuse. “It’s their fault that they were cheated.” Most cons are based on carefully selecting people you can screw. And that’s even worse. It’s one thing to outwit and brutally con somebody that’s an equal of yours, but to do it to somebody who’s not—that’s playground bully stuff.

Well, what’s the old saying, “A sucker’s born every minute”? That’s their credo.

Why that would make them feel any better about it, I can’t imagine. They’ll call up enough old people and they’ll find one who hasn’t a clue, and that’s the one they’ll zero in on. It’s just egregious cruelty.

On the flip side, based on the number of cartoons you’ve done lampooning our courts, you don’t have much confidence in the meting-out of justice in our judicial system, either. [Laughs.]

Well, I think it beats a lot of ’em, but it’s painfully obvious that the game is rigged. And as I say, I thought I was cynical, but I had no idea that it was this rigged. I didn’t know that it had been this badly skewed.Track the thing down, and it keeps going higher and higher, to points where you would’ve thought that our system took care of that. It doesn’t.

You usually portray the courts as being farcical.

I think there’s a lot of very sincere people doing their damnedest to make the thing work, but, yeah, if you’re rich and you’re well-connected and so on, there’s a lot of advantage you can take. It’s perfectly legal, and it shouldn’t be. As I say, I thought the whole thing was more honestly run. I didn’t know it was this gaffed.

The cartoon that may be the most brutal and cynical in the book, and that ought to be given some sort of award, is the one where aliens are looking at a couple of simple Neanderthal saps and saying “What possible harm can come to this planet from teaching these miserable creatures how to use fire and simple tools?”

As I say, that’s been the great shock to me in the last few months. It’s been very traumatic.

I thought I knew a lot more than I know. I suddenly realized that naïveté is bottomless. I just didn’t have a clue, and I had no idea that the gaffing was that thorough. I don’t know why not, because if you go into backward areas, where prejudice is so prevalent, it’s improved in some ways. I remember talking to one lawyer, who was saying, “Innocent until proven indigent.” And that is so painfully true. When you look at these schemes, they all track down to these horrendously awful people destroying lives.

They live with themselves quite well: doesn’t faze them.

Doesn’t faze them at all, they are very proud of it. I’ve spent evenings where I’ve wanted to break a bottle over various people’s heads. And they just sit there bragging, topping each other with these hilariously funny stories of how they’ve destroyed people’s lives.

I wanted to talk to you about how dissent from the status quo runs throughout your cartooning, without being shrill or ideological. But there is nonetheless a fundamental opposition to bullying and brutishness and the taking advantage of other people in your cartoons. I think in a way it fuels the potency of your work and gives it a little moral ballast.

I’m pointing this way indignantly and lifting my torch. Not that it does a hell of a lot. That’s the other thing, is you get to rant and rave and do all these things and notice other people in the same boat, and you realize you haven’t accomplished too much here.

[Laughs.] Well, one does what one can. Did you ever think of becoming a political cartoonist? Was that ever on your radar?

I enjoyed very much the experience of working during the summers on the Chicago Tribune, because the guy who was the editor was a neighbor of ours, and I’d made friends with him. It was quite a story. We lived in this nice apartment building and he was directly above us. He would have these parties in this large apartment, very big sprawling apartment, and they were amazing affairs because all of these hugely important politicians and businesspeople and so on would show up. He’d invite them and get them drunk, and have them make fools of themselves. I was involved in radio as a young kid, and I eventually drifted away from it because I wanted to be a cartoonist, so my drive didn’t take me there.

However, my best chum, who unfortunately has now passed on, was deeply into it, and he kept that up. He eventually ended up being Oprah Winfrey’s first large producer. The two of us worked together doing things for a stretch. I was conversant with some of these machines, which were not common at that point. One of them was a wire recorder, before the tape thing, so we recorded on a wire instead, which was impossible to edit, unless you were expert and could clip it. I had shown this thing to Maxwell, the editor, and he was just thrilled at this machine. These parties would take place on the weekend, and the people would come in and I would be there with my little recording machine. We had a first run, and it worked beautifully. He would get these toweringly important people that you saw all the time in the newspapers and heard over the radio, and he’s just get ’em sauced. Then he would bring them over to the machine and have them record some horrible drivel they were coming up with. And then, that done, he started the next party with a playing of that recording to the next bunch of big wheels, while they were just starting their first drinks. And they would laugh and chuckle, and in no time at all, of course they were bombed and doing the same exact thing. He could feed one party into the other party that way, and then he also had the pleasure of having all these things on record.

So we had a very close relationship.

I wonder where those tapes are now.

I wonder where they are, too. He was a terrific ally, and he did all kinds of nice things for me. But that’s why I say I was appalled, because I spent quite a bit of time on the inside track. And that still left me innocent. The thing that really has me wondering is what if we ever really find out how awful it really is? I don’t even want to think about it.

Our heads would explode. Do you think those parties and that technique he used enhanced your social conscience or your understanding of the world?

Definitely. It was a scary and extraordinary peek at the way it really was. These people were huge. As big as you can get. And he liked pushing them around and making them hop through hoops. And he was subtle about it. They didn’t know he was doing it. For all their cleverness, they’re not really very smart. I suppose that’s one reason why they can endure mistreating so many people.

I wonder if there is a correlation between intelligence and compassion.

I think there definitely is. I don’t think it’s reliable.

Well, that wouldn’t explain William F. Buckley.

No, it doesn’t. But I think it does relate. You can put two and two together and say, “You’ve destroyed this family and everybody in it.” They can make good excuses for themselves. They don’t perceive, in a funny way. But I think intelligence is certainly a way—well, it’s what Obama’s doing now. He’s applying simple intelligence to a lot of stuff that’s going on, and sometimes it works and sometimes it doesn’t. But that’s a big part of what separates politicians who are doing something that’s decent from those that aren’t. But then intelligence can be used by Adolf Hitlers and people like that.

Misapplied.

It’s a very depressing topic. [Laughter.]

Yes, the misuse of intelligence. That is a depressing topic. We should probably end it there.