This is one of a series of follow-up interviews with each of the four participants in our 2012 Fine Art and Cartoonists Roundtable. We will soon also publish follow-up interviews with Robert Williams, Marc Bell, and Joe Coleman.

“For me, fine art is making an investigation.” — Esther Pearl Watson

In my conversation with Esther Pearl Watson, she contrasts Art Center (where she instructs in the illustration department) and CalArts (where she recently studied). While at CalArts she discovered the pleasures and benefits of delving into a wide variety of literary texts by authors from Baudelaire to Lacan to Greenberg. She then began introducing texts to her Art Center students. However, she doesn’t make it required reading. When she told me, “I don’t know if they ever read it,” the word “unlikely” came to mind. Cynical, yes, but I’ve been doing some firsthand research over the past 50 years.

It started in 1968 when I was a student at Pratt Institute. While sitting in an English literature class one day, I listened incredulously as a student told the instructor that he should be teaching them about Marshall McLuhan, not Franz Kafka. Since then, I’ve been teaching both scholarly and studio subjects at several colleges and universities. I’m at Art Center as well, teaching Histories: of Design, of Comics and Animation. And as I see it, Esther was putting it mildly when she spoke of students’ lack of concern for critical analysis and discourse. As many other academic course instructors would also tell you — if they were being honest — far too many art students resent, and even hate, being required to take humanities classes. As they see it, any pursuit of knowledge that doesn’t directly relate to landing those six-figure salaries upon graduation is simply stealing precious time away from their portfolio projects. And Art Center students are hardly the only ones.

On the other end of the spectrum, there’s CalArts. And Cranbrook. And RISD. And anyone contemplating an art education might be wise to open their eyes to what Esther has to say.

— Michael Dooley

MICHAEL DOOLEY: You started as an illustrator, is that correct?

ESTHER PEARL WATSON: Yeah.

DOOLEY: And then went on to be a painter, and Unlovable came after that?

WATSON: Kind of around the same time, actually. I was doing illustration in New York and occasionally people would see a piece printed in The New Yorker and they’d want to buy it. But it wasn’t until I came out to California that I started exhibiting more in galleries. And that was kind of a different process. I remember because I used to get paid a lot more for selling the originals if they saw it in The New Yorker or The New York Times. And then I was shocked when I came out here showing in galleries and I had to lower my prices a little bit. It almost felt like starting from the bottom again, kind of humbling. And then just slowly as I built up collectors and more and more people started learning about my work or going to the shows, then I was able to raise my prices a little bit more and make more of a substantial living off of gallery work, whereas in the beginning it was just like an occasional piece here or there.

And it was around when we came to California that I started making Unlovable as a minicomic. Because in New York, we were making minicomics as promotional material, and not necessarily looking for them to be published, even though it did occur with Mark [Todd]’s Pain Tree. He sent that out as promo and then an editor at Houghton Mifflin got a copy and said she wanted to publish it. But it wasn’t until I came out to California and I self-published Unlovable and sent that around, that it slowly started to lead to other things. It led to doing a panel comic for Bust magazine, and then to Fantagraphics publishing Unlovable as a graphic novel. I started to see that there was a lot more potential in creating the minicomics and getting them out there.

DOOLEY: Now, the comics. Was that something you were involved with in your younger days? How did you first start to pay attention to comics?

WATSON: Yeah, but comics for me were different. I felt like when I was growing up, comics were for boys. At first, I totally ignored them. They had zero interest for me. But when I was young, like 8 to 10 years old, we moved to Italy for a little while, a couple years. And that’s the first time I started to see anime. And I really liked the anime stories, because they were more, in a way, dramatic. There was a lot of drama. And then when I came back to the United States I found some manga comics. I had a couple of them that I was very interested in. I really liked them. I liked the stories and the way the art looked. But I didn’t really read them or collect them. And we moved often and I never really brought them with me.

But the one thing that I feel like I learned to draw from the most, or I learned my comics from, was Barbie coloring books actually. Because I would trace the images and then alter them, and there was always text at the bottom. And the Catholic churches, too. I think they brought out a lot of narrative interest, the stations of the cross had these sequential images and sometimes text underneath it. And the churches in Italy with the beautiful paintings on the ceiling. I would just sit there during Mass, looking up. And you could just make up all these stories from the images. I feel like I was picking up sequential narrative imagery all around me. But not from traditional comics. [Laughs.]

Mark and I met when we were in our early twenties, and I remember going back to visit his dad’s house, and he had a whole closetful of comics. And I remember thinking, of course he would collect those, because it really fits him, and comics were for boys. And I kind of felt like comics was his world, even when he was making minicomics in New York as promotional material. Even though I always loved sequential storytelling, it wasn’t until we moved to California, where I saw other people making comics, that I got real excited. And then I was aware too of alternative comics in the papers, like the Village Voice and all that stuff. And Lynda Barry. I remember being really excited when we lived in New York that Lynda Barry was in the Mermaid Parade and stuff like that. But I felt like I was always kind of on the fringe in the comic world, and it wasn’t until much later when I realized that I can draw comics, and they can be my way, and I don’t have to use the traditional comic format. It didn’t have to look like a Sunday comic, and I don’t have to space out my type perfectly. I could do it wrong and it could be OK. I guess maybe that’s what I always was worried about: If I had tried to draw comics earlier when we were living in New York, it would just be wrong. And now I really love the fallibility of the way I draw comics.

DOOLEY: You had talked before about your interest not only in the language of storytelling but also in disrupting the narrative. So could you give examples of how that operates in your work, as distinct from say, traditional comics storytelling?

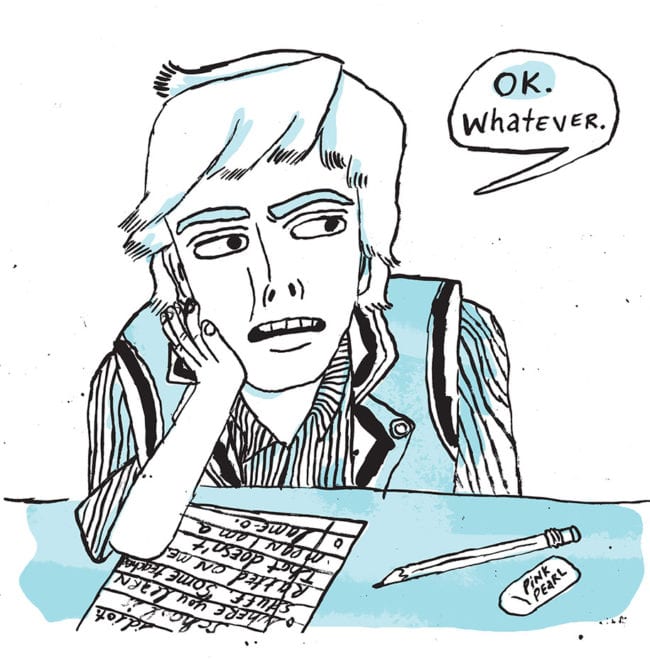

WATSON: Well, with the Unlovable zines, the number one thing I wanted to do was not draw a grid, because I felt like there’s definitely these structures of grids. I guess Ivan Brunetti was saying there’s like a democratic grid where each square has equal weight on the page, or each panel has equal weight. And then there’s a hierarchical grid, like Chris Ware, where one image is larger and then with more time there’s smaller little beats of smaller panels. And in a way I kind of felt like that was a language that was developed all over these years that wasn’t for me. I wanted to avoid the grid altogether. So when I drew Unlovable, the grid was just the page itself. And the pagination of the book: that was the only structure. Without drawing a box around it. Or sometimes boxes were drawn around certain type, accenting certain parts of type but not the image. Yeah, so it was messing with all the usual signifiers of comics. Also playing with the legibility and the type and what’s read first and second, and does that matter? And what if you could make a comic where you could pretty much open it anywhere and just start reading at random? And I feel like with Unlovable I’ve done that. Even though there is a sequence of a full year of Tammy’s life in Vol. 1 and Vol. 2 you can still kind of open it randomly, anywhere, and just laugh at the jokes.

DOOLEY: Very postmodern of you. [Laughs.]

WATSON: Yeah. [Laughs.]

DOOLEY: And in that sense, it’s somewhat similar to what Marc Bell is doing with his comics. There is no one particular entry point.

WATSON: Yes. He likes lists. I feel like a lot of his comics are just kind of lists of things.

DOOLEY: Uh huh. And this sensibility carried from Unlovable into your painting, would you say?

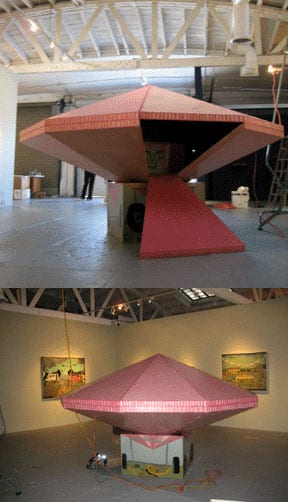

WATSON: Definitely. Especially lately, now that I’m in grad school. I’ve been trying to tie comics and painting together and even playing with the idea of the panel as painting panels and as comics panels or narrative panels. I just recently took a lot of my paintings and bolted them all together and made a giant fort that you walk into. So here’s all these paintings, and the viewer is seeing the fronts and the backs of paintings at the same time. The whole entire fort does have a narrative, but it’s all in random order. And so you have to physically walk around to read it. You have to be a very active viewer in order to figure out the story. And a lot of times, I’ve been building these boxes that attach to the paintings that contain little minicomics that you can take with you. And I like that idea as well, especially after years of working in print: to be able to physically go up to a painting and have an experience with it and be able to take a piece of it off the painting and walk away with it.

DOOLEY: So that’s like taking your own interest in having your fine art be part of an investigation and having the viewer physically make that investigation in a three-dimensional space, and over time as well. They become part of that investigation.

WATSON: Yeah. It’s a spatial, temporal experience.

DOOLEY: And you also mentioned in the roundtable that you were finding that in some instances the CalArts people were more interested in discussing your comics than your paintings.

WATSON: Yes, at times.

DOOLEY: And why would that be?

WATSON: Um, I don’t know. It’s really interesting. I mean, I’ve been puzzling that out and I think I’ve found a way to kind of work them both together. But I think, especially earlier this year, I was making what I thought should be art objects, and thinking that the comics, even though they were art objects — I still consider them art objects — I kind of kept them. I didn’t publicly acknowledge them alongside my paintings. And so when people were really surprised, like when I made those books, they were like, “Whoa, this is art, as well.” And “What you’re saying with a Xerox machine is actually very interesting, and you should pay attention to that.” Whereas I feel like maybe because I came from illustration and I have this long history of making minicomics as promotional material, I think it took me a little while to look at it from a different angle. I can make a nonlinear comic that actually says a lot and is an art object in itself. I think before I still had my children’s-book mentality of “How can this be a book proposal?” And if it’s going to be a book proposal to a publishing house, then it needs to have a narrative and a strong concept. I think as an art object, it has a concept that works or functions in a different way — in a less linear way than a book proposal. Even though it’s kind of weird because I think there’s some slippage there, because it can work as both. I definitely believe there are lots of comics out there that are art pieces.

DOOLEY: Yeah, and part of the CalArts sensibility is that idea of wandering into theory.

WATSON: Yeah.

DOOLEY: So do you think that that helped, that that fit with what you were doing with narrative?

WATSON: Yes. I definitely started looking at comics through the lens of semiotics, like OK, comics is its own specific language and it’s not that old, and who was the first to develop certain vernacular that’s used in the comics, and why do we repeat it? Why do we all latch on to repeating certain things and giving those drawn symbols significance? It’s really interesting to show my comics to some people who don’t read comics, and sometimes they are confused about how you even read the whole thing. [Laughs.] And it reminds me very much that this language is established and it’s kind of taught by reading it. Like the more you read it, the more you learn all the symbols and how they denote meaning or emotion or whatever as part of the story. And I find all that really fascinating. I try to apply that as well and look at it in a very similar way with my paintings because I feel like my paintings are very allegorical, and so I’m using a lot of the symbolic in a very similar way that I’m using the comics.

DOOLEY: And could you talk about how allegory is working in your paintings?

WATSON: I feel like with the flying saucers, using the imagery of the flying saucer, especially in some of my early pieces, they were more kind of dull, gray saucers. And then there was the narrative in the corner of the piece. And the whole thing was more like capturing a memory or a moment of my dad’s idea of the future. And then some of the later saucer paintings I’ve been doing are pink and glittery. My daughter now associates saucers with me so the saucers have changed in meaning. When I paint the pink, glittery saucers, that is now a symbol of not only the future, but it’s like a feminist future.

DOOLEY: In a sense, your works seem somewhat out of time, not necessarily present-specific. Is that a conscious decision on your part?

WATSON: I like mixing the idea of memory of the past with the present.

DOOLEY: There’s also an aspect of humor, like comics humor, in your work. Is that something that you’ve taken from your comics sensibility and consciously added it to your paintings?

WATSON: I wonder which came first: the humor in the paintings or the humor in the comics. I don’t know which came first. I think it’s from my dad who is very funny. My grandparents used humor a lot. I always had humor when I was growing up. My brothers and sisters had our weird, wacky sense of humor. I always loved that juxtaposition of humor with this painfully awkward moment, humor and failure kind of happening simultaneously. It comes out in Unlovable and it comes out in the paintings, too. And I try to capture that with everything I do whether it’s a comic panel or a painting panel.

DOOLEY: Right, and the humor was there in Unlovable, but it was also a sensitivity, rather than, say, a mocking.

WATSON: Exactly, and I think I do that with the paintings as well, because I’m definitely painting a specific socioeconomic group of American society, but I’m not making fun of growing up poor. There is this sensitivity. There’s this awkwardness and humor happening.

DOOLEY: Yeah. There’s even a bit of an overlap in the socioeconomic aspects of say, Robert and Joe’s work.

WATSON: That’s true.

DOOLEY: But their humor is very distinct from yours. [Laughs.]

WATSON: Yeah, definitely. I was thinking about that after the roundtable talk. I don’t know if it’s of that time — but their work had a much more aggressive humor to it, where it was more of a “Fuck you! Hahaha.” [Dooley laughs.] And I feel like now we can have this more subtle humor. There’s a similarity in there, but it’s softer. I wonder if that’s because their work was much more shocking when they were making it. I feel like they’ve kind of opened a door for us now where we don’t have to be that aggressive anymore. Some of the Tammy comics are aggressive, or they’re kind of rude or crude, and I feel like that would have been way more shocking back then, and now it’s not. We take a lot of stuff for granted now. And so it’s almost easier: I have a lot more freedom, I think, thanks to them.

DOOLEY: Yeah, and what they were going through, there was a need to be aggressive in order to gain the attention of the art world in a way that’s now taken for granted, or at least more acceptable.

WATSON: Oh yeah, definitely. Now you see a lot of comics and a lot of different forms and different galleries, a range of galleries from boutique to blue chip, so it’s not shocking; you just need something relevant to say to get attention.

DOOLEY: What other image makers are working in a mode that you feel an empathy with these days? You had mentioned Lynda Barry.

WATSON: Yeah, I really like Lynda Barry a lot. I feel like I’m definitely interested in artists who are trying to tell a story or trying to capture memory. I just heard Kerry Tribe speak. Her work is very different from mine; it’s not comics at all. It’s almost more of a fine-art documentary style of working. But I really like that she goes to investigate memory and really is just looking at a story from all the different angles instead of just a linear angle. And I guess that’s what I’m kind of interested in right now. I feel like I’m not necessarily looking for someone to parrot, like a gallery that’s showing comics in it, literally. I’m almost looking for other ways, unique ways to story-tell and push those boundaries of storytelling.

I’ve been looking at some really weird stuff; I guess I’m in a weird place because I was just working on my thesis show. I was looking at the idea of the Chinese gardens as a narrative, or as a comic, actually. Where you feel like you have this freedom to kind of go wherever you want, but at the same time, your path is very directed, and you walk up to a little brick window and within that window, there’s a little cherry blossom tree and it’s positioned just so it’s framed when you walk past it, so that you see the specific image. Or you come upon a stack of rocks within the garden, and it’s positioned in such a way so that it’s framed. It’s like this walk through a story. And then also I’ve been thinking a lot about panoramas as well — the whole idea of: Before people traveled so much to get away, there would be the traveling panorama show and then you can feel like you went somewhere, you were told a story about some exotic place just by experiencing art. So I’ve been looking at some kind of non-traditional ways of thinking and storytelling. And even the idea of paneling and how a story is revealed to you.

DOOLEY: And the Chinese gardens relates to the physicality of what you were doing with your fort, and what Souther Salazar is doing as well.

WATSON: Yeah, I’ve been thinking about Souther actually lately. Where you can have an actual physical experience, like an ambulatory experience within one of his comics just by walking around the little light-bulb sculptures or the little figures that he’s made in 3D. Sometimes even sitting on the paintings themselves, grinning at you. [Laughter.]

DOOLEY: The Pop Art discussion we were having during the roundtable was somewhat stuck in the 1960s, but yet there are artists now who are using that language, that Pop vernacular. Like Sue Williams, who carries on that tradition and furthers it in a different way. Do you feel an affinity with them?

WATSON: Yes, in a way. I think we even have more options now, because it is a postmodern age. At the time it was very shocking, too, to take something so banal as a Campbell’s soup can and put that in a painting, and that’s why people were so surprised by that, or were scratching their heads, like how is that art? Whereas now we’re so acclimated to that. But there’s even a wider variety where you can take YouTube videos mixed in with banal, everyday objects mixed in with painting and comics and influences of Bollywood paintings, influences that are more global than just local. It’s just like a giant hodgepodge now.

DOOLEY: A cultural mash-up.

WATSON: It’s a cultural mash-up, and it’s very difficult now to do anything that’s shocking or surprising and in a way, it kind of does give you a lot of freedom not to have to worry about that, and instead just kind of investigate your interests and say what you want to say. And even for me, asking myself, “Why are those my interests and why do I care about telling a story in a different format or different way than I already do.”

DOOLEY: Regarding CalArts, they are big on texts, on reading. So I’m curious as to the process that you went through, as an Art Center instructor coming into CalArts. What were you being introduced to that wasn’t really happening in the Art Center environment?

WATSON: Well Art Center definitely had a lot more of the formal interests at heart, and it makes a lot of sense because, especially in the illustration program that I’m in and teaching upper-term illustration students there, they’re definitely trying to hone in on a signature formal style that’s going to get them commercial work, whereas I feel like at CalArts, it was totally an about-face for me. Definitely, it was more of the concept or a philosophical approach or question that you were asking that was actually more important. Even a critical approach to a question or something that you see out in the world — a critical consideration is more important and given a lot more time. We all sit around and try to pull out the criticality within the work, whether it’s a performance or a sound-piece or whatever, than seeing whether someone has a certain style or art signature.

And sometimes I felt like, especially in the beginning, I was sometimes lost in making eye candy instead of going a little bit deeper. It’s harder to do, to kind of figure out where in art history and art theory your work fits. And what critical decision it’s taking within that context. And it was hard for me to wrap my head around, especially the first year. I knew I used certain signifiers and I just had to pretty much deconstruct them, just take apart everything I did, put them on the table and kind of ask myself: Why am I painting? Why am I telling autobiographical stories? Why am I using text within a painting? Why am I mimicking outsider art or folk art? And what do all those things mean and signify in our culture and within our history? What does it mean to use them now? Whereas Art Center, I don’t think those are the concerns of someone who’s in training to get an editorial job. If they’re considering that, then that’s cool. But I guess for practical reasons most of my students at Art Center want to make a body of work within a portfolio or a website that’s going to get them hired by an art director.

DOOLEY: So it sounds like CalArts was kind of a Marine boot camp.

WATSON: It was. It felt like boot camp, it really did. It was more-in-your-head boot camp. But it was really good. I got to read a lot of Greenberg and Reed and Freud and Lacan and everybody. Charles Baudelaire. In the beginning, too, I was like, why are we having to read about the flâneur and the dandy — who cares! And now I feel like it makes sense, understanding where the modern sublime began and where the postmodern sublime began. I love learning and it’s been a lot of fun. But I only have a month left, and I’m very excited to finally be done and then hopefully get some sleep. [Laughter.] And read what I want to read. [Laughter.]

DOOLEY: Did you bring any of that CalArts sensibility back into your illustration instruction at Art Center.

WATSON: Oh yeah, it’s really interesting. Definitely, I noticed I’m a different teacher already. And I can tell that because I have always co-taught with Mark, and while I’ve been going to CalArts, we’ve had a lot of debate over even critiques and what the purpose of the critiques should be in class. Before we used to have everybody line their work up on the wall and then Mark and I would go through and say, “The composition’s off,” or “You need to work on your colors,” or “Perhaps you should take a typography class.” Whereas I take more of an editorial role now. I kind of feel more like I want the student to talk more and learn to articulate what it is and why they’re doing what they’re doing. And I also feel like it’s too authoritarian for me to stand up in front of the class and act like I have the right answers. Because I see that’s extremely subjective. My idea of what makes a beautiful illustration is my own personal taste, and maybe that’s not my job to impose my own personal taste on every student, but instead to bring out who they are and what they have to say with their work. So it’s a little different.

DOOLEY: And what’s been the students’ reception to that introduction?

WATSON: I think it causes a stronger dynamic between Mark and I when we’re in the class.

DOOLEY: Well, they’re still getting the Art Center line from Mark, but you’re adding another layer then.

WATSON: Definitely, yeah. They’re getting a bonus. [Laughter.]

DOOLEY: Do you give them texts to read as well?

WATSON: I have been introducing texts more. But I don’t force them to read it. Some people will take the reading, but I don’t know if they ever read it because we don’t usually talk about the readings.

DOOLEY: So your approach to teaching them — yours and Mark’s — the lesson plan is still to make them illustrators rather than fine artists?

WATSON: Well, I actually feel like that’s been changing a lot, because it’s not true for us anymore and we’re extremely aware of that, so we’re not imposing something that’s not realistic on our students. And actually this last class, we had one student who was definitely more interested in becoming a fine-art painter. Even though we would assign him illustration-based assignments, he always approached it as a fine-art painter, which was really interesting. But we always encourage students to approach work in different ways. We teach a publishing class and the final assignment was actually experimental animation. We didn’t expect any of the students to have any previous animation experience, we just wanted them to hammer out a story or a narrative no matter how abstract, and animate it in some form. And so some people were doing paper cutouts and some people knew After Effects or had taken a motion class, but most of them had not. They were cutting out of cardboard or making a painting and then figuring out how to make parts of it move. So we’re not necessarily passing along traditional assignments.

DOOLEY: And it sounds like an open-ended assignment, where to do the animation they don’t necessarily have to do storyboard sequence.

WATSON: Exactly. We’re extremely open-ended and I think some people get really shell-shocked by that, because it’s been our experience, too, that we have to come up with our own projects and ideas and then find where they fit in the world, and then somehow get paid for them so we can pay our bills. We kind of train our students for that, and we try to encourage them to develop as many tools as they possibly can that they’re interested in, because their career won’t necessarily stay on a single, linear path.

DOOLEY: I’m curious about SVA, because that’s one school where cartooning has been taken seriously for quite some time as part of their curriculum.

WATSON: Yeah, I’m curious about that as well. I haven’t been to one of their cartooning classes or seen their students’ work just yet. But next week Mark and I are going to go speak at the University of Wisconsin in Madison. Hopefully we’ll get to step in and say hello in Lynda Barry’s class that she’s teaching there. I’m sure that’s probably a fun cartooning class to take. [Laughs.]

DOOLEY: Yeah, she’s a bit of a pioneer and iconoclast as well, really.

WATSON: Yeah.

DOOLEY: And what is it about her that you admire?

WATSON: Well, I think she’s such a personality. I don’t know, when you’re around her you just feel this larger-than-life energy. She’s funny and loud and real and, on a dime, starts crying. [Laughs.] And the next moment laughing and singing and just this giant tornado of emotion and energy. And you’re really acutely aware that she’s taking in everything. She knows what it is to be alive. She’s just zapping all that air around her. Just like charging it with this energy and taking everything in. I really like that. There’s some people in this world who are so alert and so present. They’re so lucid. And then there’s some people in this world where you can just see the glaze over their eyes. They’re missing everything around them like they’re not quite alive. And it’s really something special, I think when you’re around someone who just really appreciates everything about the moment they’re in. I think it makes you a little more alert and awake as well.

DOOLEY: Any other examples, any people you can think of offhand that are similar, that have that kind of energy to offer?

WATSON: I would definitely say Matt [Groening]’s that way too, you can tell. I’m just really amazed how good he is around people. He always comes across as very warm and friendly. I’ve even seen him in situations where I would be uncomfortable, where people start rushing up to him. They start running up to him and you can tell he’s going to get stuck being surrounded by people, and he’s still extremely easygoing and finds this really natural, easy way out of all kinds of human traffic. [Laughter.] You can tell he’s just very aware and remembers people and what they say.

I feel like I’ve met so many really great people. I wish I could just have a big picnic [laughter] and invite all the great people that I’ve met over the years. There’s just some really good people. And Martha Rich is really great, too. She moved to Philadelphia to go to grad school and, boy, do we miss her. She just came out to visit, and I wasn’t even aware of how much she makes a difference. Being around her makes a huge difference. All our friends just came out of the woodwork, and we were hanging out a lot. She just makes you laugh about silly things, and all your worries seem so trivial. She just gets you to laugh at life, and that’s a good feeling to be around someone like that.

DOOLEY: One thing I appreciated in your definition of what constitutes fine art is that you had mentioned not only making an investigation but also asking a question and not necessarily providing an answer. Could you expand on that? Because I feel that the fine-art works that do manage to survive are the ones that are open-ended enough that future generations can continue to find room to move around in.

WATSON: I think that’s important to remember: You don’t have to provide the answer every time. I feel like as an illustrator, I’m a problem solver; I’m given this text and I need to find the answer. But I really feel like there’s a lot of great pieces that are a little more open. And you can allow the viewer to intellectually ask questions and let them be questioned as well. And you can ask yourself questions, too. I feel like really great works of art do that. Like even Duchamp’s urinal where some people are still scratching their heads and asking if that’s art, or what does that mean or was that a joke or was he serious? But I kind of like that we can still ask ourselves that today.

DOOLEY: Yeah, and the great thing is that it is that open-ended. I mean, it is a joke and he was serious. [Laughter.]

WATSON: Yeah, that’s true.

DOOLEY: When I teach Duchamp in my design-history class, I point out that he started out as a single-panel cartoonist, and the idea of taking his titles into consideration as captions, it wasn’t just upending the urinal, it was also calling it Fountain —

WATSON: Exactly.

DOOLEY: — that also added even more layers.

WATSON: I know. I think it takes a lot of courage, too, to make art and put it out there in this world that perhaps you don’t understand 100%, or you don’t have all the answers to.

DOOLEY: Well, are there any other thoughts, something else that you’d like to add?

WATSON: No, I remember right after the roundtable I had so many thoughts. I kept thinking about it, what people said and the difference between Marc Bell and I, and the other two guys. But no, it was actually really interesting. That was such an interesting conversation. I really enjoyed it.

DOOLEY: Oh, yeah. The tangents were often so fascinating that I just wanted to let them play themselves out. “Go with it.” [Laughter.] And Robert talking about the difference between reading a comic-inspired painting and the comic itself was having resonance with some of what you were talking about.

WATSON: Yeah, it was really interesting. I’d love to talk to Robert Williams some more. I thought he had really great advice. And Joe Coleman’s stories were just getting crazier and crazier. [Laughter.] Which is perfect, because it totally fits his personality.

DOOLEY: Yeah. At this point, I still have to interview Marc and Robert, but I did have the follow-up conversation with Joe already, and he was quite a different person one-on-one.

WATSON: Oh, he was?

DOOLEY: There was a gentleness in our follow-up that wasn’t happening when “the two guys” got together.

WATSON: True, there were hints of gentle moments and then lots of bravado. [Laughter.]

DOOLEY: It was an energizing conversation nevertheless.

WATSON: It was, yeah.