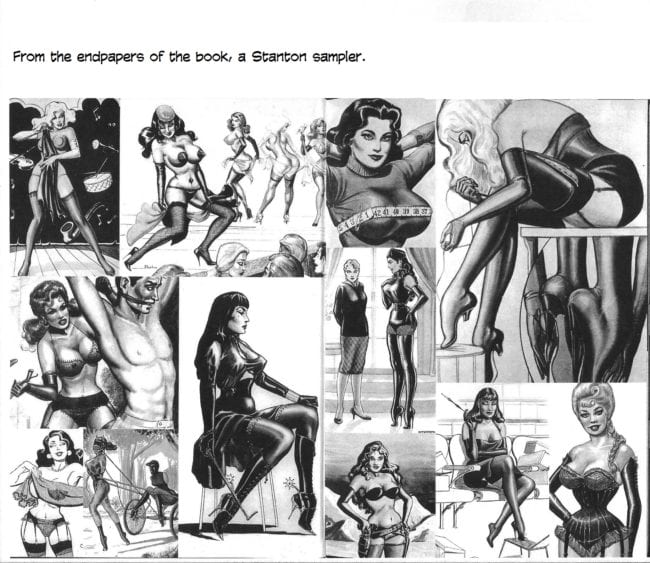

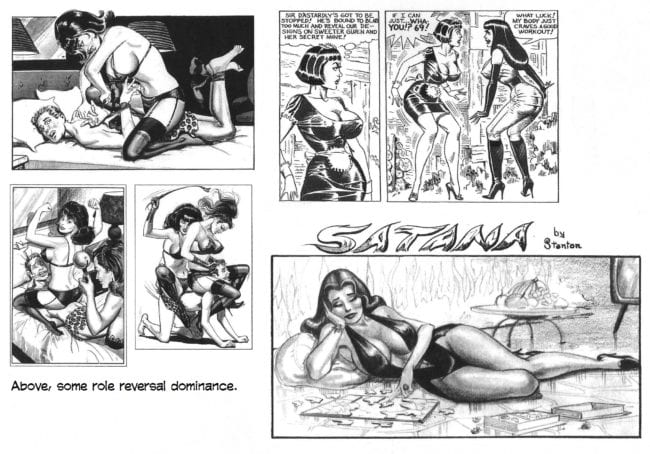

STANTON IS A FASCINATING FIGURE in cartooning for at least two reasons. First, he could draw beautiful sexy women but chose to portray them in physical combat or bound, strapped, and gagged in the best dominance tradition. Why he did that is a question for his psychoanalyst, not me. I’m more fascinated by his work than his psyche.

The other fascinating aspect to Stanton is that he probably helped Steve Ditko invent Spider-Man.

St. Wikipedia sums him up this way (avoiding Ditko):

Eric Stanton was an American underground cartoonist and fetish art pioneer.

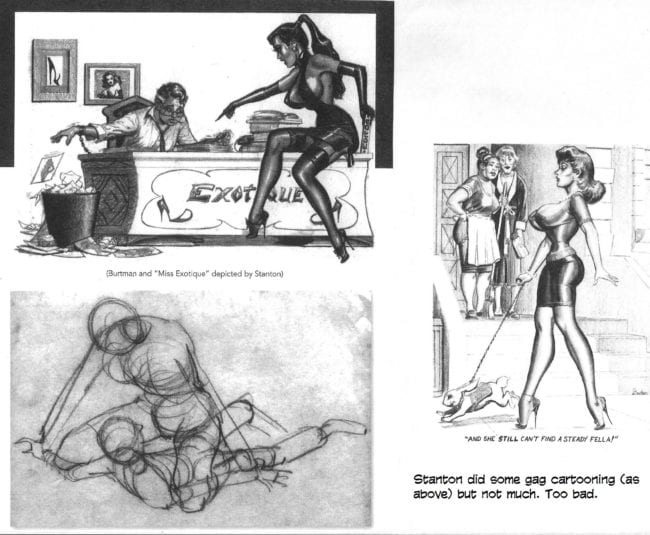

While Stanton began his career as a bondage fantasy artist for Irving Klaw, the majority of his later work depicted gender role reversal and proto-feminist female dominance scenarios. Commissioned by Klaw starting in the late 1940s, his bondage fantasy chapter serials earned him underground fame. Stanton also worked with pioneering underground fetish art publishers, Leonard Burtman, the notorious Times Square publisher.

The details of Stanton’s life and some representation of his work I’ve taken from Eric Stanton & the History of the Bizarre Underground by Richard Perez Seves (288 7x8-inch pages, b/w and some color; 2018 Schiffer Publishing hardcover, $29.99).

Author Seves, who says on the book jacket’s back flap that he is a collector “obsessed” with vintage American fetish art, musters impressive research in the book: he dug into FBI reports, court records, Navy documents, the New York State Census, previous books about Stanton (Eric Kroll’s The Art of Eric Stanton and other tomes), as well as such obvious sources as Belier Press publications and many obscure periodicals (Comics Buyer’s Guide!?). And he interviewed many persons who either knew Stanton or others of the fetish milieu. The book has an index and is copiously footnoted in the back by page number, which notes add substantial information to the narrative as well as citing Seves’ extensive sources.

His text is accompanied throughout by lots and lots of illustrations, many in color, and Seves gives the histories of several of Stanton’s serials and tells their stories. The book is virtually an extensively annotated bibliography of Stanton’s life work. But it’s more than that. It’s also a detailed biography, a sketchy history of “the bizarre,” and an exhibition of Stanton’s ladies. Reproduction throughout is high quality.

Among the illustrations are three consecutive pages from his celebrated Sweeter Gwen, a retake of John Willie’s classic Sweet Gwendoline.

The book’s only scholarly flaw is Seves’ failure to caption the illustrations; they are usually explained in the adjacent text, but you have to look hard for it. A photograph of an attractive middle-aged woman we determine is Stanton’s mother only because the text nearby is about her.

Stanton (birth name, Ernest Stanzoni, Jr.) was born September 30, 1926 in Brooklyn. Ernest Sr., it turns out, was not his biological father. Ernest Jr. was the result of a fling his mother, Anna, had in the early years of her marriage. Ernest Jr. enlisted in the Navy upon graduation from high school in June 1944. Discharged in 1946, Stanton took advantage of the G.I. Bill, which paid $20/week for a year to finance vets’ search for jobs; he was actually loafing, living at home, and playing softball and shooting dice with friends. After the G.I. Bill funding expired, he worked in a nightclub with his stepdad (his mother having divorced Ernest Sr. and re-married). And he drew pictures in his spare time—often of fighting women.

In 1948, a softball friend introduced him to an uncle, cartoonist Boody Rogers, and Stanton assisted him for a year, helping out with a quarterly comic book, Babe: Darling of the Hills, and the somewhat less regularly published Sparky Watts, the four-color reincarnation of a newspaper comic strip Rogers had produced in the early 1940s about a superpowered guy with spectacles. By late 1949, Rogers’ publisher had abandon both titles. Rogers gave up cartooning and moved to Arizona, where he opened a pair of art-supply stores that were successful and sustained him until his death February 6, 1996 at the age of 91.

During his last months with Rogers, Stanton was also producing work for Irving Klaw. Klaw, self-named the "Pin-up King," was a merchant of sexploitation, fetish, Hollywood glamour pin-up photographs, and underground films. His business, which eventually became Movie Star News, began in 1938 when he and his sister Paula opened a basement level struggling used bookstore on 14th St. in Manhattan.

STANTON HAD SEEN an ad in Whisper or another of the soft-core girlie magazines of the day. The ad touted a cartoon “serial” published by Klaw, and Stanton sent off for it. Cartoon serials, of which Stanton would make a life’s work, were published in “chapters” that consisted of a sequence of drawings accompanied by text narratives, the text often just typewritten and pasted next to the pictures. Some took shape as comic strips with speech balloons, but those were relatively rare.

The serial Stanton sent for depicted fighting women. The drawings were okay, Stanton thought, but he believed he could draw female combat better so he wrote Klaw, saying he’d like to do something for him. Klaw invited him to submit samples, which Stanton promptly did. And soon, he was drawing regularly for Klaw at $15 a page. When the Rogers’ enterprise collapsed, Stanton quickly turned full-time to producing fetish art.

Although Stanton preferred doing fighting women, Klaw also wanted bondage serials, and Stanton supplied them. Ditto serials about dominating women, who subjected other women—and men—to successive physical humiliations. Stanton always generously deployed high heels, gartered stockings, and long legs to satisfy the general fetish reader.

Seves does a little credible psychoanalysis along the way:

Almost at once Stanton recognized that art provided a unique satisfaction he did not experience in real life: not only access to a special fantasy world, but a sense of personal power: ‘I had control ... I could have the people I drew do anything I wanted’ he reflected in later years. ‘I was king of my world.’ Control and powerlessness—as mirrored in the secret subculture of the sexual fantasist–would become a major theme in his art. [...]

Something in Stanton’s psychological makeup dictated channeling and creating art as a means of attaining a proper balance and some measure of control in his life. The actual art he made—the artifact itself—was always less important than the process. [...] It was the process of making art that Stanton lived for; it was that process of exploration and discovery.

And Seves quotes Stanton’s son Tom, who said that Stanton “said sex is the bottom line of the psychology of people. Sexploitation, particularly fetish art, became a means of exploring the human psyche. He saw these stories—many of them—not simply as ‘porn,’ but as journeys of self-discovery. Sex was just the key that unlocked the door.”

Or maybe Stanton just liked drawing sexy women for the pure thrill of it.

In 1951, Stanton married Grace Marie Walter on October 20; they had two children, both boys. The same year, Stanton enrolled in the Cartoonists and Illustrators School founded by Burne Hogarth. Stanton took courses from Hogarth and from Jerry Robinson, and in Robinson’s class, he met Ditko and Eugene Bilbrew, an African-American artist who Stanton would introduce to Klaw. As Eneg (“Gene” spelled backwards), Bilbrew, like Stanton, would pursue a career in fetish art.

Ditko, asked years later how he and Stanton met, said, “I liked the way he drew women.” More about their relationship anon.

Over the years, Stanton would produce work for several merchants of fetish art: Edward Mishkin, who ran a store near Times Square (in those days, the neighborhood of sexploitation with dozens of stores selling girlie magazines, photographs, movies, and smut); Leonard Burtman, publisher and merchandiser; Max Stone, publisher of fighting female serials; and Stanley Malkin, also a Times Square entrepreneur, who would hire Stanton, putting him on salary, to do covers for his magazines—Stanton’s longest salaried situation as a fetish artist, 1963-68. Malkin also furnished and paid all the expenses for a small apartment for Stanton.

All, plus Klaw, were eventually arrested, tried and convicted of trafficking in pornography (“printed circulars, pamphlets, booklets, drawings, photographs and motion picture films, which were non-mailable in that they were obscene, lewd, lascivious, indecent, and filthy”). After serving their sentences (usually payment of a fine), all returned to their businesses under different names—except Malkin, who gave it up in 1969.

Stanton’s wife, unfortunately for him, was fiercely opposed to the work her husband did, thoroughly repulsed by it. To please her, he eventually took a full-time job delivering parts for Pan Am, doing only a little drawing in his spare time. Lifting a heavy part one time, he strained his back, and the pain would stay with him for the rest of his life, often becoming severe enough that he could not get out of bed. He began taking prescription painkillers and eventually graduated to other drugs. Finally, he discovered the remedial effects of yoga and practiced the discipline regularly.

Since he was unable to lift anything because of his back, Stanton lost his job at Pan Am. He returned to drawing full time. In 1958, he and Grace separated, and in 1960, Stanton sued for divorce, which was granted June 3 in Las Vegas, where quickie divorces were readily accomplished.

THE SAME YEAR that he and Grace separated, Stanton joined Ditko in a studio at 276 W. 43rd Street and revived the camaraderie of their C&IS days.

“Ditko welcomed Stanton as his studio mate,” reports Seves, “—thus initiating one of the most unique, synergetic, and confounding partnerships in comics art history. In the peculiar way that opposites sometimes attract, the Stanton/Ditko association almost seemed to make sense. Here was Ditko, the unyielding comic artist who was disinclined to draw women; here was Stanton, the mutable fetish artist who was uninterested in depicting men.

“Ditko’s material showed a total unawareness of sex while Stanton’s material conveyed a kooky preoccupation with it. Yet both shared the same ambition of make it as artists; and both, one might say, were earnest and obsessed.”

“We had a great working relationship,” Stanton recalled in a 1988 interview. “We were the only guys who could have gotten along with each other.”

Says Seves: “One could only imagine how gratifying Ditko’s presence must have been to Stanton after his time with Grace; from being around someone who was repulsed by art to being around someone whose very waking moment was consumed by it. ‘There were times Steve would spend twenty hours straight doing a comic,’ Stanton remembered.

“And Ditko was completely accepting of Stanton: ‘He thought my stuff was funny. We’d laugh a lot,’ Stanton said, as he fondly remembered years later. ‘Every experience that I had with Steve was terrific, as far as I was concerned.’”

The studio was bare bones. “It was a room about ten feet by twenty,” said Stanton. “One side was all windows. Steve’s desk and mine faced each other next to the window.”

It was, in short, just the kind of setup that encouraged the two artists to kibbitz each other’s work. And also to lend each other a hand when deadlines loomed.

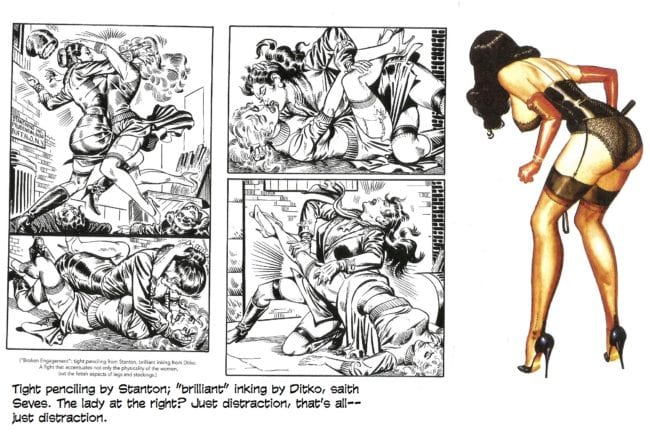

Seves accepts without qualification that Stanton helped Ditko and that Ditko helped Stanton. On full-fledged collaborations, Stanton usually did the pencils; Ditko, the inks. Stanton drew the women; Ditko, the men. And Seves points out evidence of Ditko’s hand in various of Stanton’s enterprises.

More in this vein anon.

After a short spell living in the cramped quarters of a room at the YMCA, Stanton went to live at his mother’s home. She, by this time, was also single. He worked all day at the studio, and then, at home in the evenings, he worked some more. He “withdrew from dating and any contact with women,” Seves says. “The next time he had sex, it was with a prostitute that his mother had sent because she was so concerned about him, and she didn’t want him to give up on women.”

The Stanton-Ditko studio lasted until 1968, when they both set out again on their own. That year, Stanton met Britt Stromsted, a Norwegian woman visiting the U.S. Unlike Grace, Britt was fascinated by Stanton’s artistry, and she even modeled in wrestling poses with Stanton, photos he’d use as references when drawing fighting femmes.

They married in Norway in 1971—and again in 1980 in Manhattan. This marriage was a happy one and resulted in two children, a boy, Tom, and a girl, Amber.

In 1969 when Malkin gave up his business, he left Stanton his mailing lists, altogether 20,000 names and addresses. Using the lists, Stanton started his own business, a mail order operation repackaging and selling his work as “Stanton Archives” and doing commissions.

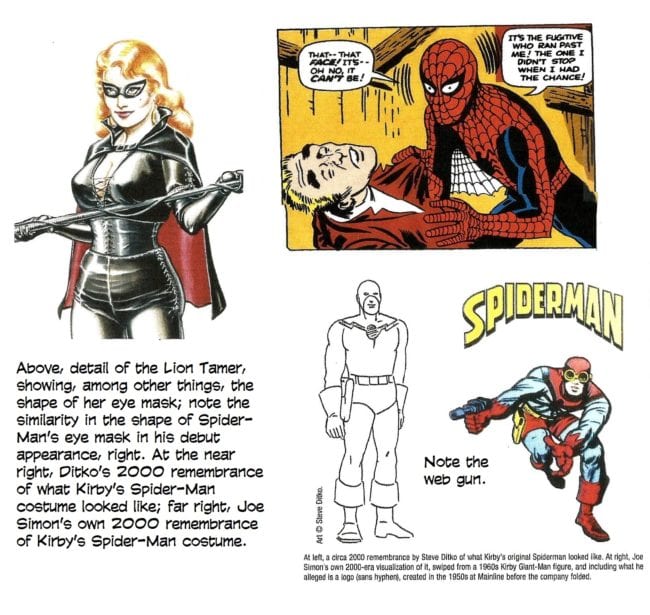

SEVES MAKES A CONVINCING CASE that Stanton contributed to the 1962 creation of Spider-Man. Among the evidence he offers are simple coincidences. First among these is the 1962 publication of Stanton’s Black Widow Sorority, which features a character wearing a spiderweb costume, which, for Spider-Man, is translated into a full-body suit “much like a fetish latex body suit,” Seves observes.

I suppose it could be the other way around: Ditko’s Spider-Man costume influenced Stanton’s costuming of the Black Widow Sorority. Nah.

Spider-Man’s face mask is unusual among superheroes. The mask covers the entire face. “Prior to Spider-Man,” Seves writes, “heroes had open faces (like Superman) or half-faces (like Batman).”

Seves quotes Ditko about the full-face mask: “I did it because it hid [Peter Parker’s] obviously boyish face. It would also add mystery to the character and allow the reader/viewer the opportunity to visualize, to ‘draw,’ his own preferred expression Peter Parker’s face and, perhaps, become the personality behind the mask.”

But if no superhero had a full-face mask, Seves asks, where did Ditko get the idea?

“Would it be fair to say from bizarre culture? Or, specifically, from Stanton since he had been creating hooded characters for almost as long as he had been a fetish artist?”

Seves also points out that the first issue of a magazine containing the inaugural installment of Stanton’s Sweeter Gwen was likely on Stanton’s drawing board when Ditko returned from Marvel with his new assignment—create Spider-Man. And the back cover of the magazine featured the full-figure portrait of a “kinky lion tamer” wearing an eye-mask the shape of which was echoed in Spider-Man’s eye-mask.

Coincidences are not causation. But they may have had some influence. Seves creates an imaginary scene at Ditko’s drawing board when Stanton, interested in Ditko’s latest assignment from Marvel, gets up from his drawing board and walks to Ditko’s side and looks over his shoulder at the pages Ditko had spread out in front of him—pages that Jack Kirby had drawn, depicting Spider-Man, visuals that Stan Lee had rejected before turning the assignment over to Ditko.

“Whatcha got there?” Stanton might have begun.

Given the working relationship between the two artists in their studio—the kibitzing back and forth, the brainstorming about page layouts and plots— what Seves suggests is entirely plausible. He quotes Greg Theakston, who conducted an interview with Stanton in 1988—:

“Together he and Ditko would have ‘skull sessions’ and choreograph many of the great action sequences throughout the books.”

Pointing to the Kirby sketch, Ditko might have disparaged the web gun Kirby’s character was brandishing: “That idea is old.”

“Maybe it shoots from his wrist,” Stanton might have said, demonstrating a maneuver with his hand and fingers.

In fact, while Stanton usually denied having influenced Ditko’s conception of Spider-Man—“Steve doesn’t like me to talk about him,” he told Theakston, “my contribution to Spider-Man was almost nil”— he sometimes admitted that the web-shooter idea was his.

Then, quickly, as if not to offend his old pal in absentia, “but the whole thing was created by Steve on his own. The whole thing was Steve Ditko.”

Finally, there’s Peter Parker’s Aunt May. According to Stanton’s son Tom, “Aunt May was my dad’s Aunt May, his babysitter from childhood, when he was sick a lot.”

Peter Parker may not have been sick a lot as a child, but his self-esteem was low, and he was as withdrawn and hesitant as if he had missed most of his childhood, laying in bed with some illness or another.

STANTON’S DAUGHTER Amber wrote about her father’s contribution to Ditko’s creation of Spider-Man in an article, “A Tangled Web,” originally published in The Creativity of Steve Ditko (2012). She remembered watching with the family the Macy’s Thanksgiving Day parade on tv when she was nine years old. As a giant balloon of Spider-Man appeared on the screen, her father exclaimed: "Would you believe that— I never would have thought," she quotes her father saying with amusement.

When she asked him what was so unbelievable, he confessed that he’d helped another artist, naming Steve Ditko, create the character. And he told her what he’d contributed.

Wrote Amber: “My father contributed to the costume, the idea of the web shooting out of Spider-Man's wrist, and the movement which he made with his hands to release the web. ... I still remember my father's beautiful, strong, broad hands as he showed me the movement that makes Spider-Man's web release from his wrist. It was just like my dad to come up with something like that. If you knew my father it would make sense that he had a hand in Spider-Man.”

Her mother was angry that Stanton never claimed recognition or royalties because of his role in creating the character. When Amber asked her father about it, “his response,” she said, “made it clear that it was something he would never even consider because the ideas were freely given.

“Their friendship,” she added, “was centered around creating art. Each of them contributed to the other's art as part of the friendship between two artists. While each was the driving force behind his own work, there was significant overlap. Steve contributed to the erotic stories my father worked on and my father contributed to Spider-Man and probably other stories. Neither one of them ever expected any recognition or money from the other.”

While Stanton wanted to honor Ditko’s work by not claiming any part of it for himself, he had another reason for avoiding the subject: he wanted to protect his family by keeping a low profile:

“He explained that since Spider-Man was so famous, it might draw attention to him as an artist if people knew he contributed to the creation of the character,” Amber wrote. “My brother and I were children and in school, and he feared that it could negatively effect our lives if people knew he was an erotic fetish artist.”

Amber said her father always spoke highly of Ditko’s art, particularly his inking ability. “When they collaborated,” she said, “my father did the pencil work, and Steve would ink over it.”

After her father’s death, she found Ditko’s phone number and called him. She wanted to know if he had any memories he could share. He couldn’t remember anything, she reported, and he denied that her father had anything to do with creating Spider-Man.

She remembered her mother telling her that Ditko had a very black-and-white view of the world. Her mother explained that when her father told Ditko that he had fallen in love and was going to have a family, Ditko “reacted with anger and disapproval. He believed people should not have children because the world was an awful place.” It was at this point that the Stanton-Ditko studio broke up.

IT’S RISKY to believe such witnesses—Stanton and his daughter: both have some vested interest in hitching their wagons to a star like Ditko. But Seves supports their beliefs, and his book includes several examples of pages from the Stanton oeuvre that display drawings clearly in Ditko’s style.

Some instances that Seves cites are not quite so convincing: if Ditko did them, he did them by dutifully imitating his studio-mate’s mannerisms to the extent that his own disappear. Or so it seems to me, but I’m scarcely a Ditko expert.

Stanton seldom saw his erstwhile studio-mate in the years after they broke up the studio. He continued doing work until his death March 17, 1999, as “the most famous fetish artist in the world,” as Seves puts it.