There are some artists who seem to arrive fully in control of their aesthetic and their vision from the outset of their career. As they deliver new work over time, their development seems so subtle and incremental that it is barely discernible to the uninitiated. But when an audience becomes versed in the artist’s language—visual or otherwise— they can detect and delight in this seemingly imperceptible (but no less apparent growth). For these kinds of artists, reinvention is unnecessary because the artist’s ability to access that magical space of familiar novelty with greater ease becomes the reason to keep showing up. Every addition to their body of work seems of a preconceived whole. Even as themes and tropes are re-hashed, they sparkle with greater clarity and deeper nuance. There is comfort in their familiarity. The work transcends the limitations of the medium to achieve an emotional tone.

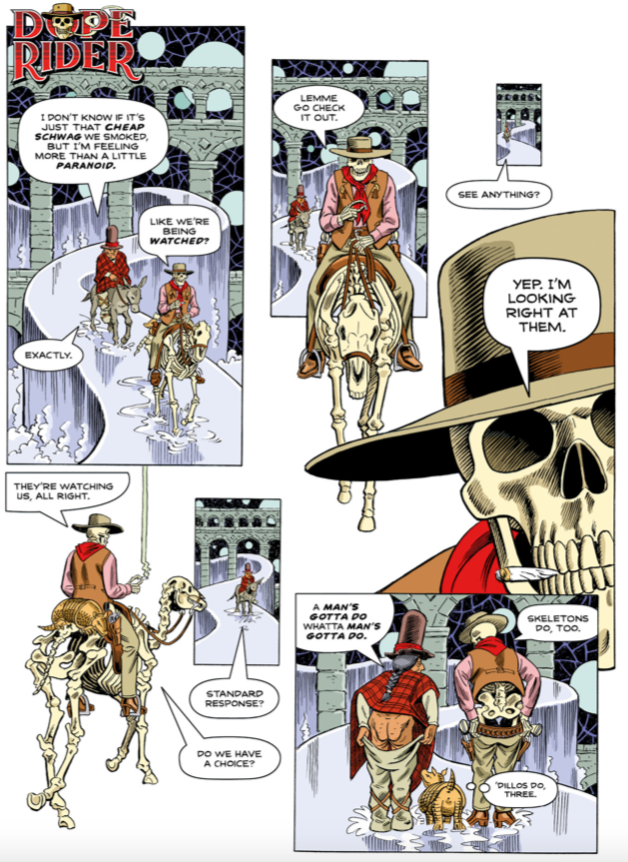

Paul Kirchner is an artist who occupies this pantheon. His latest for French publisher Tanibis Editions, Dope Rider: A Fistful of Delirium, is an easygoing, casual collection of the Dope Rider strips published in High Times magazine after 2015. The collection does not dwell on the fact that it is Kirchner’s momentous return to the famous (in some circles) character after some 30 years. These strips find Kirchner breathing new life into the motifs and conventions for which he and his strip are known. While he doesn’t break any new ground here, he does demonstrate his ever-increasing mastery of perspective, page layout, and, above all, pure illustration. Despite the strip’s brevity (each installment is just a single page) Dope Rider gets at subjects from the mystic to the mundane. In the span of just a few panels, he satirizes, celebrates, and deconstructs both the stoner culture in which Dope Rider has its roots and the wider pop culture in which that subculture is seated. Kirchner doesn’t shy away from employing the insular vernacular of weed culture, but also seems aware of its goofiness and, to some degree, its staleness.

While the book celebrates weed in its every iteration, it arrives in a transitional moment for marijuana culture. Given that marijuana is now fully legal in fourteen states and has been decriminalized or authorized for medical use in many others, High Times magazine and the contents therein cannot make the same claims to countercultural subversion that it once could. Still, marijuana’s place in the zeitgeist is not entirely settled. Depending on who you talk to and when, blanket federal legalization is either extremely imminent or extremely impossible. Kirchner leaves these matters to the professionals, unremarked upon. This is for the better. The world of Dope Rider is separate from ours, one outside of time and space. While it shares our world’s amenities, it does not share its problems. The level of conflict is the same level you would find in any gag strip because that’s essentially what Dope Rider is.

Stoner jargon aside, Dope Rider has a low barrier to entry and asks very little of the reader. Kirchner treats the strip like a playground and, for the reader, taking a ride can be a thrill, at least until the novelty wears off. Luckily, it’s just as easy to walk away in favor of something else as it is to jump back on for another spin later. Like any trip, Dope Rider offers insight if you’re game. The only sense of continuity in these pages comes in the form of recurring characters. Kirchner eschews any narrative or character development that isn’t in service to a bit or a gag and the bits and gigs are in service to visual inventiveness and his exploration of surrealism, perspective, and his breaking the confines of the medium. Rendered in Kirchner’s confident hand, the strip reads as natural and understated, no matter how out there it gets. In working in such a limited space, Kirchner’s work in Dope Rider feels all the more outsize. In one strip, the titular character acknowledges and addresses the reader. In another, a character implores the reader to go buy Paul Kirchner books. These clever turns never feel overwrought or overburdened with metatextual import as they might when employed by other cartoonists. They are outcomes that fall squarely within the anything goes logic of cartooning. The packaging of these strips highlights their brevity and allow the reader to focus on strip at time, as they are presented as one strip per set of facing pages with the opposite facing page being a frame in a Dope Rider flip book in which the titular character, a skeleton dressed in cowboy garb, manifests from a smoky ashtray and rides a joint like a rocket in acrobatic loops before sky-writing a marijuana leaf in smoke. Again, Kirchner isn’t reinventing the wheel here. Again, it would feel like padding if it came from the pen of a lesser cartoonist.

Stoner jargon aside, Dope Rider has a low barrier to entry and asks very little of the reader. Kirchner treats the strip like a playground and, for the reader, taking a ride can be a thrill, at least until the novelty wears off. Luckily, it’s just as easy to walk away in favor of something else as it is to jump back on for another spin later. Like any trip, Dope Rider offers insight if you’re game. The only sense of continuity in these pages comes in the form of recurring characters. Kirchner eschews any narrative or character development that isn’t in service to a bit or a gag and the bits and gigs are in service to visual inventiveness and his exploration of surrealism, perspective, and his breaking the confines of the medium. Rendered in Kirchner’s confident hand, the strip reads as natural and understated, no matter how out there it gets. In working in such a limited space, Kirchner’s work in Dope Rider feels all the more outsize. In one strip, the titular character acknowledges and addresses the reader. In another, a character implores the reader to go buy Paul Kirchner books. These clever turns never feel overwrought or overburdened with metatextual import as they might when employed by other cartoonists. They are outcomes that fall squarely within the anything goes logic of cartooning. The packaging of these strips highlights their brevity and allow the reader to focus on strip at time, as they are presented as one strip per set of facing pages with the opposite facing page being a frame in a Dope Rider flip book in which the titular character, a skeleton dressed in cowboy garb, manifests from a smoky ashtray and rides a joint like a rocket in acrobatic loops before sky-writing a marijuana leaf in smoke. Again, Kirchner isn’t reinventing the wheel here. Again, it would feel like padding if it came from the pen of a lesser cartoonist.

Mandala designs, occult esoterica, high desert vistas, and dusty roads of the old west variety are what comprise the world of Dope Rider. But while the landscape may speak to Salvador Dali, Sergio Leone, and Alejandro Jodorowsky, the dialogue and visual gags, which are peppered with pop culture references belie a certain “normal dude” sensibility. Kirchner serves this visual feast with a side of cultural junk food, much of which is past the expiration date. He makes allusions to the likes of Lord of the Rings, The Matrix, and Spongebob Squarepants. Even considering the original publication they are somewhat stale. In a way, it adds to the charm as it demonstrates a self-awareness, a reluctance to stray to far afield of what he knowns. As Kirchner has stated in multiple interviews, he’s no head, no psychonaut, and his straight down the middle cultural references reflect that.

The vast majority of Kirchner’s body of work - from Dope Rider to The Bus to Hieronymus & Bosch - has been produced under constraints, both self-ascribed and editorial, of physical dimension and length. With a background in both comics anthologies and advertising, Kirchner knows how to command the reader’s attention with limited time and space. He does this by making his limited real estate as appealing as possible, which, in turn, makes the time the reader spends in that world as pleasurable as it can be and invites re-visitation. It’s hard to say that all comics aspire to this, especially when viewing comics as an industry, rather than a medium. But Kirchner’s body of work makes this plain and he succeeds at it.